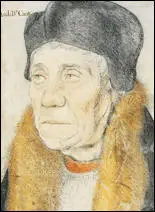

Archbishop William Warham

William Warham was born in Oakley, Hampshire, in about 1450. It is believed his father, Thomas Warham, worked as a carpenter. It appears that someone in the family was wealthy and William was educated at Winchester College and New College, Oxford, where he became a fellow in 1475 and acquired a doctorate in canon law. (1)

In 1496 Warham became the archdeacon of Huntingdon. Later that year he was involved in the negotiations for the marriage of Prince Arthur to Catherine of Aragon. (2) In 1501 he was sent as a diplomat to Emperor Maximilian I. The following year he became Archbishop of London. At the request of Pope Julius II he was appointed as Archbishop of Canterbury on 29th November 1503.

As his biographer, John Scarisbrick, has pointed out: "After a distinctly slow start, therefore, he had suddenly soared to the highest office in the royal government and the supreme ecclesiastical dignity of archbishop of Canterbury, legatus natus, and primate of all England. Since he was by then well over fifty, neither he nor others could have expected that he would have a further claim to fame, that of almost being Canterbury's longest-serving archbishop." (3)

William Warham - Archbishop of Canterbury

Archbishop William Warham crowned the new king, Henry VIII, at Westminster on 24th June 1509. However, he had doubts about the legality of the marriage: "It is not only inconsistent with propriety, but the will of God is against it. It is declared in his law that if a man shall take his brother's wife, it is an unclean thing. It is not lawful." (4) As Lord Chancellor he was concerned with the day-to-day legal and formal administration business of the government. He delivered the customary speeches at the opening of four parliaments, and on two occasions led a formidable delegation to the lower house to demand assent to heavy taxation.

Roger Lockyer has claimed that Henry VIII preferred clerics to nobles in his administration: "The big advantage of these men from Henry's point of view, was that they were well educated, could be rewarded for service to the state by promotion in the Church (which cost Henry nothing) and left no heirs with a legitimate claim to either their wealth or their offices." (5)

Under Henry VII, England had avoided continental war. His son, by contrast, longed for war against France. This policy was very unpopular with Archbishop Warham who publicly spoke in favour of peace in the House of Lords. (6) Other members of the Royal Council, including Thomas More, who "thought it wisdom to sit still and let them alone" and advised peace against the hazard and cost of war. Wolsey supported Henry and suggested that he joined the Holy League with Pope Julius II and his father-in-law, Ferdinand of Spain, so that they might with papal approval attack France. The alliance was agreed on 13th November 1511 and war was declared the following month. (7)

On 22nd December, 1515, William Warham resigned the Lord Chancellorship, which passed to Thomas Wolsey. It has been reported by Edward Hall that he had been dismissed by Henry VIII. However, Thomas More reported that he had been told by Warham that he was glad to quit. "After eleven years as chancellor the archbishop may have resolved to devote himself entirely to his spiritual duties. Possibly the whole truth contains all these views. Warham had probably never been cordial with the young king, who had inherited him from his father, and could never have competed with the dashing, self-confident, and much younger Wolsey." (8)

Catherine of Aragon

In 1526 Henry VIII began a relationship with Anne Boleyn. The historian, Eric William Ives, has argued: "At first, however, Henry had no thought of marriage. He saw Anne as someone to replace her sister, Mary (wife of one of the privy chamber staff, William Carey), who had just ceased to be the royal mistress. Certainly the physical side of his marriage to Catherine of Aragon was already over and, with no male heir, Henry decided by the spring of 1527 that he had never validly been married and that his first marriage must be annulled.... However, Anne continued to refuse his advances, and the king realized that by marrying her he could kill two birds with one stone, possess Anne and gain a new wife." (9)

Catherine was in a difficult position. Now aged 43, she found it difficult to compete with Anne. "Now her once slender figure was thickened with repeated child-bearing, and her lovely hair had darkened to a muddy brown, but visiting ambassadors still remarked on the excellence of her complexion. A dumpy little woman with a soft, sweet voice which had never lost its trace of foreign accent, and the imperturbable dignity which comes from generations of pride of caste, she faced the enemy armoured by an utter inward conviction of right and truth, and her own unbreakable will." (10)

It was suggested that Catherine should agree to annul the marriage. Alison Weir, the author of The Six Wives of Henry VIII (2007) believes that if she agreed to this measure Henry would have treated her well. "Yet time and again she had opposed him, seemingly blind to the very real dilemma he was in with regard to the succession, and when thwarted Henry could, and frequently did, became cruel." (11) Alison Plowden argues that for Catherine it was impossible to accept the deal being put forward: "Henry's partisans have accused his first wife of spiritual arrogance, of bigotry and bloody-mindedness, and undoubtedly she was one of those uncomfortable people who would literally rather die than compromise over a moral issue. There's also no doubt that she was an uncommonly proud and stubborn woman. But to have yielded would have meant admitting to the world that she had lived all her married life in incestuous adultery, that she had been no more than 'the King's harlot', the Princess her daughter worth no more than any man's casually begotten bastard; and it would have meant seeing another woman occupying her place. The meekest of wives might well have jibbed at such self-sacrifice; for one of Catherine's background and temperament it was unthinkable." (12)

Henry sent a message to the Pope Clement VII arguing that his marriage to Catherine of Aragon had been invalid as she had previously been married to his brother Arthur. Henry relied on Cardinal Thomas Wolsey to sort the situation out. During negotiations the Pope forbade Henry to contract a new marriage until a decision was reached in Rome. With the encouragement of Anne, Henry became convinced that Wolsey's loyalties lay with the Pope, not England, and in 1529 he was dismissed from office. (13) Wolsey blamed Anne for his situation and he called her "the night Crow" who was always in a position to "caw into the king's private ear". (14) Had it not been for his death from illness in 1530, Wolsey might have been executed for treason.

While the negotiations concerning her divorce were going on, Queen Catherine was exiled from the Court and was refused permission to see or communicate with her daughter. In April 1533 she was told that she had to renounce her title of Queen and would in future be regarded simply as Arthur's widow, with the rank of Princess Dowager. Thomas Howard, 3rd Duke of Norfolk informed her: "She need not trouble any more about the King, for he had taken another wife." Catherine wrote to King Charles V of Spain warning of the great dangers facing the Catholic faith. She told him that "what passes here every day is so ugly and against God and touches the honour of the King my lord so nearly, that I cannot bear to write it." (15)

Henry VIII ordered Catherine to choose the lawyers who would act as her counsel; she could pick from the best in the realm, he said. She choose Archbishop William Warham and John Fisher, the Bishop of Rochester. George Cavendish was an eyewitness to the submission of Catherine of Aragon during divorce proceedings. He quotes her saying: "Sir, I beseech you, for all the loves that hath been betrayed us, and for the love of God, let me have justice and right. Take of me some pity and compassion, for I am a poor woman and a stranger born out of your dominion. I have here no assured friend, and much less indifferent counsel. I flee to you as the head of justice within this realm. Alas, Sir, where have I offended you? Or what occasion have you of displeasure, that you intend to put me from you? I take God and all the world to witness that I have been to you a true, humble and obedient wife, ever conformable to your will and pleasure. I have been pleased and contented with all things wherein you had delight and dalliance. I never grudged a word or countenance, or showed a spark of discontent. I loved all those whom you loved only for your sake, whether I had cause or no, and whether they were my friends or enemies. This twenty years and more I have been your true wife, and by me you have had many children, though it hath pleased God to call them out of this world, which hath been no fault in me." (16)

Dispute with Henry VIII

Elizabeth Barton, of St Sepulchre's Nunnery, began having visions. Elizabeth had meetings with Edward Bocking, a monk at Christchurch Priory. Under his guidance, she began to experience revelations of a controversial character. Elizabeth, now known as the Nun of Kent, was taken to see Archbishop William Warham and Bishop John Fisher. Both were impressed by her revelations and she was advised to see Cardinal Thomas Wolsey. She told him that she had seen a vision of him with three swords - one representing his power as Legate (the representative of the Pope), the second his power as Lord Chancellor, and the third his power to grant Henry VIII a divorce from Catherine of Aragon. (17)

Wolsey arranged for Elizabeth Barton to see the King. She told him to burn English translations of the Bible and to remain loyal to the Pope. Elizabeth then warned the King that if he married Anne Boleyn he would die within a month and that within six months the people would be struck down by a great plague. He was disturbed by her prophesies and ordered that she be kept under observation. Archbishop Thomas Cranmer commented later that Henry put off his marriage to Anne because "of her visions". (18) Warham was accused of encouraging the actions of Elizabeth Barton.

On 24th February 1532, Warham made a statement when he repudiated anything done by Henry VIII since November 1529 that "violated the rights of Rome, ecclesiastical authority, or the privileges of his metropolitical see". On 15th March, Warham went further and stood up in the House of Lords and openly attacked the king for his conduct. He was accused of treason but died, aged about 82 on 22nd August 1532.

Primary Sources

(1) John Scarisbrick, William Warham : Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (2004-2014)

It was later suggested that two other people helped to make the archbishop ‘harder and less to favour the king's cause’: one was John Fisher, who allegedly did all he could to ‘embolden’ him; the other was Elizabeth Barton, reputed ‘the Holy Maid of Kent’, whom Warham had treated with circumspection when she first claimed to have visions, but who may have impressed him when she later denounced the royal divorce and warned him, and Wolsey, not to "meddle" further in the matter, else they would be "utterly destroyed". That, at any rate, is what was claimed at her execution in November 1533.

Whatever the truth of this, on 24 February 1532, in an upper room in Lambeth Palace, Warham swore to a public instrument repudiating anything done or henceforth done since November 1529 that violated the rights of Rome, ecclesiastical authority, or the privileges of his metropolitical see. All were publicly condemned. That was provocative enough, but, according to the Venetian ambassador in London, on the following 15 March Warham went further. He stood up in the Lords and openly upbraided the king for his conduct.

Student Activities

Henry VIII (Answer Commentary)

Henry VII: A Wise or Wicked Ruler? (Answer Commentary)

Henry VIII: Catherine of Aragon or Anne Boleyn?

Was Henry VIII's son, Henry FitzRoy, murdered?

Hans Holbein and Henry VIII (Answer Commentary)

The Marriage of Prince Arthur and Catherine of Aragon (Answer Commentary)

Henry VIII and Anne of Cleves (Answer Commentary)

Was Queen Catherine Howard guilty of treason? (Answer Commentary)

Anne Boleyn - Religious Reformer (Answer Commentary)

Did Anne Boleyn have six fingers on her right hand? A Study in Catholic Propaganda (Answer Commentary)

Why were women hostile to Henry VIII's marriage to Anne Boleyn? (Answer Commentary)

Catherine Parr and Women's Rights (Answer Commentary)

Women, Politics and Henry VIII (Answer Commentary)

Cardinal Thomas Wolsey (Answer Commentary)

Historians and Novelists on Thomas Cromwell (Answer Commentary)

Martin Luther and Thomas Müntzer (Answer Commentary)

Martin Luther and Hitler's Anti-Semitism (Answer Commentary)

Martin Luther and the Reformation (Answer Commentary)

Mary Tudor and Heretics (Answer Commentary)

Joan Bocher - Anabaptist (Answer Commentary)

Anne Askew – Burnt at the Stake (Answer Commentary)

Elizabeth Barton and Henry VIII (Answer Commentary)

Execution of Margaret Cheyney (Answer Commentary)

Robert Aske (Answer Commentary)

Dissolution of the Monasteries (Answer Commentary)

Pilgrimage of Grace (Answer Commentary)

Poverty in Tudor England (Answer Commentary)

Why did Queen Elizabeth not get married? (Answer Commentary)

Francis Walsingham - Codes & Codebreaking (Answer Commentary)

Codes and Codebreaking (Answer Commentary)

Sir Thomas More: Saint or Sinner? (Answer Commentary)

Hans Holbein's Art and Religious Propaganda (Answer Commentary)

1517 May Day Riots: How do historians know what happened? (Answer Commentary)