On this day on 17th December

On this day in 1778 Humphry Davy, a woodcarver's son, was born in Penzance. After being educated in Truro, Davy was apprenticed to a Penzance surgeon. In 1797 he took up chemistry and was taken on by Thomas Beddoes, as an assistant at his Medical Pneumatic Institution in Bristol. Here he experimented with various new gases and discovered the anesthetic effect of laughing gas (nitrous oxide).

Davy published details of his research in his book Researches, Chemical and Philosophical (1799). This led to Davy being appointed as a lecturer at the Royal Institution. He was a talented teacher and his lectures attracted large audiences.

In 1806 Davy published On Some Chemical Agencies of Electricity. The following year he discovered that the alkalis and alkaline earths are compound substances formed by oxygen united with metallic bases. He also used electrolysis to discover new metals such as potassium, sodium, barium, strontium, calcium and magnesium.

Davy was now considered to be Britain's leading scientist and in 1812 was knighted by George III. His biographer, David Knight, wrote: "On 8 April 1812 Davy was knighted by the prince regent, and on the 11th he and Jane Apreece were married by the bishop of Carlisle at Jane's mother's house in Portland Place. They spent their honeymoon in Scotland, staying with eminent people; Davy took his little apparatus with him, and conducted some researches on gunpowder. He gave up his courses of lectures, and wrote up his Elements of Chemical Philosophy the same year. This, dedicated to Jane, dealt with his own work, and was meant to be the first of a multi-volume set, but it did not sell well, for it was not a satisfactory textbook and his researches were accessible in the Royal Society's Philosophical Transactions."

Michael Faraday saw Davy lecture in 1813: "Sir H. Davy proceeded to make a few observations on the connections of science with other parts of polished and social life. Here it would be impossible for me to follow him. I should merely injure and destroy the beautiful and sublime observations that fell from his lips. He spoke in the most energetic and luminous manner of the Advancement of the Arts and Sciences. Of the connection that had always existed between them and other parts of a Nation's economy. During the whole of these observations his delivery was easy, his diction elegant, his tone good and his sentiments sublime." In 1813 Faraday became his temporary assistant and spent the next 18 months touring Europe while during Davy's investigations into his theory of volcanic action.

In 1815 Humphry Davy invented a safety lamp for use in gassy coalmines, allowing deep coal seams to be mined despite the presence of firedamp (methane). This led to some controversy as George Stephenson, working in a colliery near Newcastle, also produced a safety lamp that year. Both men claimed that they were first to come up with this invention. Stephenson wrote in The Philosophical Magazine in 1817: "The principles upon which a safety lamp might be constructed I stated to several persons long before Sir Humphrey Davy came into this part of the country. The plan of such a lamp was seen by several and the lamp itself was in the hands of the manufacturers during the time he was here."

One of Davy's most important contributions to history was that he encouraged manufacturers to take a scientific approach to production. His discoveries in chemistry helped to improve several industries including agriculture, mining and tanning. Sir Humphry Davy died on 29th May 1829.

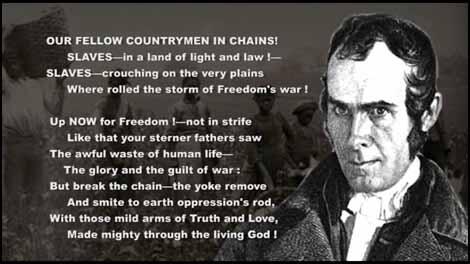

On this day in 1807 John Greenleaf Whittier, the son of a Quaker farmer, was born in Haverhill, Massachusetts. Although he received only a limited formal education, he developed a strong interest in literature. When he was only 19 he had a poem, The Exile's Departure, accepted by William Lloyd Garrison, in the Newburyport Free Press. The two men became close friends and they worked together in the campaign against slavery. His pamphlet, Justice and Expediency, made him a prominent figure in the Anti-Slavery Society.

Whittier's first book to be published was, Legends of New England in Prose and Verse (1831). This was followed by two long poems, Moll Pitcher (1832) and Mogg Megone (1836). Poems Written During the Progress of the Abolition Question appeared in 1838.

Whittier edited the Pennsylvania Freeman (1838-40) and wrote several anti-slavery poems included The Yankee Girl, The Slavery-Ships, The Hunters of Men, Massachusetts to Virginia and Ichabod. His poems on slavery were collected as Voices of Freedom (1846). Whittier's concern for the suffering of others was well illustrated in his book, Songs of Labour (1850).

Whittier was a regular contributor to the Atlantic Monthly. Other volumes of verse include the Chapel of the Hermits (1853), Panorama (1860), In War Time (1864), Snow-Bound (1866), Tent on the Beach (1867), Among the Hills (1869), Miriam and Other Poems (1871), Hazel-Blossoms (1875), The Vision of Echard (1878), Saint Gregory's Guest (1886) and At Sundown (1890). John Greenleaf Whittier died on 7th September, 1892.

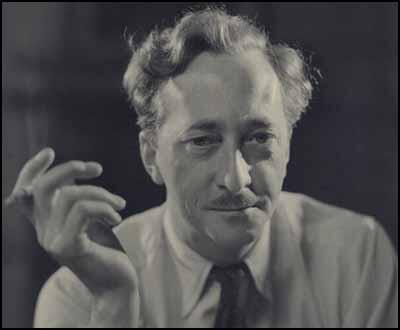

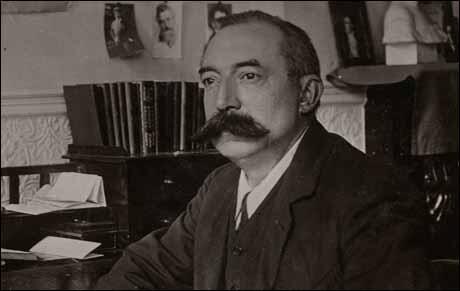

On this day in 1873 novelist Ford Hermann Hueffer, the son of Francis Hueffer, the music critic of The Times, was born. He was also the grandson of the artist, Ford Madox Brown. Hueffer published his first book, The Brown Owl (1891), when he was only eighteen. This was followed by the novel, The Shifting of Fire (1892).

In 1894 Hueffer eloped with and married Elsie Martindale. He met Joseph Conrad and together they co-authored several works including The Inheritors (1901) and Romance (1903). His most successful books during this period was the trilogy, The Fifth Queen (1906), the story of Catherine Howard.

In 1908 Hueffer founded the English Review and over the next 15 months he published the work of Thomas Hardy, H. G. Wells, D. H. Lawrence and Wyndham Lewis. Huseffer's support of modernism did much to shape the course of 20th century writing.

In June 1914, Hueffer's published the first part of his novel, The Saddest Story, in Blast Magazine. The full version, retitled, The Good Soldier, A Tale of Passion, appeared in 1915, and is now considered to be the most important of the 80 books that he produced during his lifetime.

Soon after the outbreak of the First World War, Hueffer was recruited by Charles Masterman, the head of Britain's War Propaganda Bureau (WPB), to write pamphlets that would help shape public opinion. Hueffer, embarrassed by his German name and heritage, was the most passionate of all the writers that worked for the WPB. Hueffer's first contribution, When Blood is Their Argument, was an attack on German literature, art and music. In the pamphlet Ford claimed that the German education system had spread the "rot of Prussian culture throughout he world".

Hueffer followed this with Between St. Dennis and St. George, a reply to Common Sense about the War, a pamphlet written by George Bernard Shaw that had been highly critical of Sir Edward Grey and the government's foreign policy. Hueffer also took the opportunity to attack Britain's pacifist intellectuals, such as H. N. Brailsford, Fenner Brockway, Norman Angell and Bertrand Russell, In the pamphlet Hueffer described these men as "pro-Prussian apologists".

In 1916 Hueffer abandoned his career as a propagandist and joined the British Army. He was sent to France in July 1916 as a junior officer in the 38th Infantry Brigade. Hueffer served in the transport division and therefore never involved in trench warfare. However, his experiences with the dead and dying in the military hospitals made him question the role he had played in persuading so many men to join the armed forces. Especially when he discovered that the incompetence of Britain's military leaders was causing the unnecessary deaths of large numbers of soldiers. .

At Mametz Wood, where the 38th Infantry Brigade suffered heavy casualties during the Battle of the Somme, Hueffer was knocked unconscious by a nearby exploding shell and suffered concussion. Hueffer blamed General Henry Rawlinson for the disaster at Mametz Wood and deeply upset by the loss of so many comrades, was later to write: "I don't think that many of those who were one's comrades did not at times feel a certain hopelessness. And so they would sit in the chairs of the lost and forgotten. You will say this is bitter. It Is. It was bitter to have seen the 38th Division murdered in Mametz Wood - and to guess what underlay that."

In 1919 Hueffer changed his name to Ford Madox Ford. Three years later he moved to Paris where he founded the Transatlantic Review. Over the next year Ford published the work of several important new writers including James Joyce and E. E. Cummings. In the 1930s Ford published two volumes of autobiography, Return to Yesterday (1931) and It was the Nightingale (1933). Ford Madox Ford died in 1939.

On this day in 1885 the artist Charles Jagger was born. He left school aged fourteen to learn the craft of engraving on silver with the Sheffield firm of Mappin and Webb. He also studied at the Sheffield School of Art in the evenings.

In 1907 Jagger he won a scholarship to the Royal College of Art, South Kensington. According to Ann Compton: "After four years there as student and assistant to Professor Edward Lantéri, a travelling bursary enabled him to study for some months in Rome and Venice." In 1914 he won the Rome scholarship in sculpture. However, on the outbreak of the First World War he decided to to enlist in the Artists' Rifles instead. Other members of the regiment included Edgell Rickword, Bert Thomas, Barnes Wallis, Edward Thomas, Paul Nash, John Nash and John Lavery.

In 1915 Jagger was awarded a commission in the 4th battalion of the Worcestershire Regiment and was sent to Gallipoli. Later he was transferred to the 2nd battalion on the Western Front. He was wounded and while recovering in England he married Violet Constance Smith.

Jagger returned to the front-line and was awarded the Military Cross. He was also gassed and wounded and once again he received medical treatment in England. Instead of being sent back to France, Jagger was commissioned by the British War Memorials Committee to produce a large relief, entitled the First Battle of Ypres.

After the war Jagger established a studio in South Kensington. His work was dominated by his experience in the trenches and in 1923 he produced the relief, No Man's Land. After being cast in bronze it was presented to the Tate Gallery in 1923.

Jagger's next major work was Tommy and Humanity. According to his biographer: "The bold modelling of the Tommy, combined with the energy and strength the figure conveyed, was an outstanding achievement. The expressiveness of this work was an instant success at the Royal Academy, where it was exhibited in 1921, and resulted in many more commissions." Jagger admitted that his art reflected the admiration he felt for the work of Alfred Gilbert and Auguste Rodin.

Over the next seven years Jagger completed war memorials in Manchester (1921); Southsea (1921); Bedford (1921); Great Western Railway War Memorial (1922); Brimington (1922); Royal Artillery Memorial (1921–5); Anglo-Belgian War Memorial (1922–3); Nieuwpoort (1926–8); Cambrai (1927–8); and Port Tawfiq (1927–8).

During this period Charles Jagger produced statues of the Duke of Windsor (1922), Lord Hardinge (1928) and Ernest Shackleton (1932). Alfred Mond, the founder of Imperial Chemical Industries, commissioned four large stone figures symbolic of industries for the company headquarters in Millbank.

Charles Sargeant Jagger died of pneumonia at his home, 67 Albert Bridge Road, Battersea, on 16th November 1934.

On this day in 1887 Cyril Bird, the son of the England cricketer, Arthur Bird, was born in Cheltenham on 17th December 1887. After attending Cheltenham College (1902-04), Bird he studied engineering at King's College and took art classes at Regent Street Polytechnic and the Bolt Court School of Photo-Engraving.

In 1904 he became a machine-gun instructor in the Artists' Rifles. Later he was employed at the Rosyth Naval Dockyard (1909-1914). On the outbreak of the First World War he became an officer in the Royal Engineers. He reached the rank of lieutenant when he was blown up by a shell at Gallipoli in 1915. His injuries were so bad he was not expected to survive.

Invalided out of the British Army, Bird's cartoons first appeared in Punch Magazine in 1916. He used the name Fougasse (a type of French anti-personnel mine) to avoid confusion with another Punch contributor W. Bird (Jack B. Yeats). Bird later recalled that his cartoons were like the fougasse "its effectiveness is not always reliable and its aim uncertain". Bird also contributed to The Bystander, The Daily Graphic, The Tatler, London Opinion and The Sketch.

Bird's style was notable for what one critic called its "pronounced linear simplicity." Like Henry Mayo Bateman, another cartoonist who worked for Punch Magazine during the war, Bird often adopted an episodic format. Mark Bryant pointed out that at first he drew like Bert Thomas "but gradually developed his own style (motoring and radio being frequent subjects)."

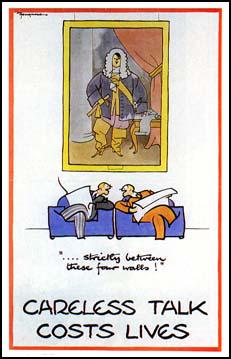

Bird became Art Editor of Punch Magazine in 1937 and during the Second World War designed several posters for various government departments including his famous Careless Talk Costs Lives series for the Ministry of Information depicting Adolf Hitler listening to conversations. For this work he was awarded the honour of Commander of the Order of the British Empire in 1946.

It has been argued that Bird pioneered the idea that humour is more important than art. He once said that "it is really better to have a good idea with a bad drawing than a bad idea with a good drawing". According to Mark Bryant: "His distinctive, strikingly economical style, often using only a few lines but expressing great dynamism, is immediately recognizable and has influenced many artists."

R.G.G. Price, the author of A History of Punch (1957) has argued that "clarity and speed were everything in his work and he was constantly trying to simplify... he rapidly developed a personal style that was perhaps the first introduction of advertising technique to the editorial pages of Punch."

In 1949 Bird was appointed editor of Punch Magazine. He was the first cartoonist to be given this position and held the post until his retirement in 1953. Cyril Bird, who was married to the watercolour artist, Mary Holden Caldwell, died on 11th June 1965.

On this day in 1903 Walter Greenwood was born in Salford, Lancashire. He came from a poor working class family and left the local council school in Langworthy Road at the age of 13. According to his biographer, Geoffrey Moorhouse: "He inherited the family tradition of determined radicalism, enthusiasm for books, and love of music, which fostered his ambition to escape from the life of the industrial slum. His father had died of alcoholism when he was nine and his mother supported them by working as a waitress. The family experience was typical of many in the area at the time, long stretches of unemployment alternating with brief periods of ill-paid and usually manual work."

Greenwood did a succession of poorly paid jobs but continued to educate himself by visiting the Salford Public Library. While out of work he wrote Love on the Dole (1933). This novel of life in a northern town during the depression was a great commercial success. Moorhouse argues: "The strength of Love on the Dole as a novel lies not in its descriptions or its narrative but in the honesty with which it tells its story of urban poverty and in the richness and accuracy of its dialogue. It is occasionally comic, it ends in tragedy, and it is essentially an account of courage in desperately universal circumstances... It became a landmark in its original form because it vividly told recognizable truths when the country was suffering them in the slump."

It was expected that Greenwood's success would enable him to marry his long-term fiancée Alice Miles, who had formed the basis for Sally Hardcastle, the heroine of his novel. He changed his mind, however, and she sued for breach of promise in January 1936,. He settled out of court and instead married Pearl Alice Osgood, an American actress.

Greenwood followed Love on the Dole with novels such as: His Worship the Major (1934), The Time is Ripe (1935), Standing Room Only (1936), Cleft Stick (1937), Only Mugs Work (1938), The Secret Kingdom (1938) and How the Other Man Lives (1939). He also wrote articles for Picture Post.

During the Second World War Greenwood formed Greenpark Productions Ltd and produced films for the British government. he also served in the Royal Army Service Corp. Other books by Greenwood included Something in my Heart (1944), So Brief the Spring (1952), What Everybody Wants (1954) and Down by the Sea (1956).

In later life Greenwood moved to Douglas, Isle of Man and published his autobiography, There Was a Time in 1967. Walter Greenwood died in 1974. His manuscripts and letters were bequeathed to Salford University

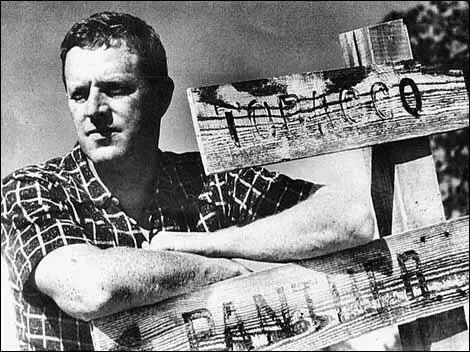

On this day in 1903 Erskine Caldwell, the son of a missionary, was born in Coweta, Georgia. As a child he travelled with his father and developed a concern for the poor. He was educated at the University of Virginia but did not graduate.

Caldwell moved to Maine in 1926 where he began writing for various journals including the New Masses and the Yale Review. He also published several novels but it was not until Tobacco Road (1932), a novel about the plight of poor sharecroppers, that critics began to take notice of his work. Dramatized by Jack Kirkland in 1933, it made American theatre history when it ran for over seven years on Broadway.

His next novel, God's Little Acre (1933) was also about poor whites living in the rural South. Both novels dealt with social injustice and many people objected to the impression it gave of America. When the New York Society for the Prevention of Vice tried to stop the book from being sold, Caldwell took the case to court and with the testimony of critics such as H. L. Mencken and Sherwood Anderson, won his case.

In 1936 Erskine Caldwell met and married the photographer, Margaret Bourke-White. They collaborated on You Have Seen Their Faces (1937), a documentary account of impoverished living conditions in the South. Other books by the couple included Russia at War (1942), North of the Danube (1975) and Say, is This the U.S.A.? (1977).

During the Second World War he worked as a newspaper reporter in the Soviet Union. An account of his experiences appeared in All Out on the Road to Smolensk (1942) and Call It Experience (1951). By the late 1940s Caldwell had sold more books than any author in America's history. God's Little Acre alone sold over fourteen million copies. His attacks on poverty, racism and the tenant farming system, had a significant impact on public opinion.

Caldwell wrote numerous short stories: collections include Jackpot (1940) and The Courting of Susie Brown (1952). Essays on his travels throughout the United States appeared in Around About America (1964) and Afternoons in Mid-America (1976). Erskine Caldwell died in Arizona on 11th April, 1987.

On this day in 1907 a large demonstration is held by the Men's League for Women's Suffrage in London. Although the majority of men opposed the idea of women voting in parliamentary elections, some leading male politicians supported universal suffrage. This included severals leading figures of the Labour Party, including James Keir Hardie, George Lansbury, Harold Laski, Gerald Gould and Philip Snowden. Another Labour politician, Frederick Pethick-Lawrence, helped to fund Votes for Women newspaper and provided bail for nearly a thousand members of the Women's Social and Political Union (WSPU) who were arrested for breaking the law.

Robert Cecil, one of the main figures in the Conservative Party was also a supporter but most were totally opposed to the idea of votes for women. Several members of the Liberal administration, such as David Lloyd George, also favoured women being granted the vote.

In 1907, several left-wing intellectuals, including Henry Nevinson, Laurence Housman, Charles Corbett, Henry Brailsford, C. E. M. Joad, Israel Zangwill, Hugh Franklin, Henry Harben, Gerald Gould, Charles Mansell-Moullin, and 32 other men formed the Men's League for Women's Suffrage "with the object of bringing to bear upon the movement the electoral power of men. To obtain for women the vote on the same terms as those on which it is now, or may in the future, be granted to men."

At a by-election in Wimbledon in 1907 Bertrand Russell, stood as the Suffragist candidate. Evelyn Sharp later argued: "It is impossible to rate too highly the sacrifices that they (Henry Nevinson and Laurence Housman) and H. N. Brailsford, F. W. Pethick Lawrence, Harold Laski, Israel Zangwill, Gerald Gould, George Lansbury, and many others made to keep our movement free from the suggestion of a sex war."

In 1909 the Men's League for Women's Suffrage published a list of prominent men in favour of women's suffrage. This included 83 former government ministers, 49 church leaders, 24 high-ranking army and navy officers, 86 academics and the writers E. M. Forster, Thomas Hardy, H. G. Wells, John Masefield and Arthur Pinero. By 1910 it had ten branches in Britain.

The Men's League for Women's Suffrage had no political party affiliation, was non-militant in its methods, but supported both the Women Social & Political Union and Women's Freedom League. The MLWS concentrated on "propagandist work". Charles Mansell-Moullin was one of the most active of the members. In a letter that he had published in The Daily Mirror on 22nd November 1910, he complained about how the police were treating members of the WSPU during demonstrations: "The women were treated with the greatest brutality. They were pushed about in all directions and thrown down by the police. Their arms were twisted until they were almost broken. Their thumbs were forcibly bent back, and they were tortured in other nameless ways that made one feel sick at the sight... These things were done by the police. There were in addition organised bands of well-dressed roughs who charged backwards and forwards through the deputation like a football team without any attempt being made to stop them by the police; but they contented themselves with throwing the women down and trampling upon them."

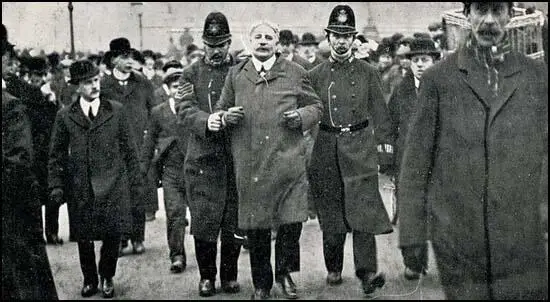

In October, 1912, George Lansbury decided to draw attention to the plight of WSPU prisoners by resigning his seat in the House of Commons and fighting a by-election in favour of votes for women. Lansbury discovered that a large number of males were still opposed to equal rights for women and he was defeated by 731 votes. The following year he was imprisoned for making speeches in favour of suffragettes who were involved in illegal activities. While in Pentonville he went on hunger strike and was eventually released under the Cat and Mouse Act.

C. E. M. Joad was another member of the Men's League for Women's Suffrage: "I joined the Men's Political Union for Women's Enfranchisement, hobnobbed with emancipated feminists who smoked cigarettes on principle, drank Russian tea and talked with an assured and deliberate frankness of sex and of their own sex experiences, and won my spurs for the movement by breaking windows in Oxford Street for which I spent one night in custody."

Evelyn Sharp later commented: "It is impossible to rate too highly the sacrifices that they (Henry Nevinson and Laurence Housman) and H. N. Brailsford, F. W. Pethick Lawrence, Harold Laski, Israel Zangwill, Gerald Gould, George Lansbury, and many others made to keep our movement free from the suggestion of a sex war."

Dr. Charles Mansell-Moullin joined forces with Sir Victor Horsley and Dr. Agnes Savill to write a report on the impact of the forced-feeding of suffragettes. In a speech on 13th March, 1913 he argued that Reginald McKenna, the Home Secretary, had been making misleading statements to the House of Commons: "Now Mr. McKenna has said time after time that forcible feeding, as carried out in His Majesty's prisons, is neither dangerous nor painful. Only the other day he said, in answer to an obviously inspired question as to the possibility of a lady suffering injury from the treatment she received in prison, "I must wait until a case arises in which any person has suffered any injury from her treatment in prison."... He relies entirely upon reports that are made to him - reports that must come from the prison officials, and go through the Home Office to him, and his statements are entirely founded upon those reports. I have no hesitation in saying that these reports, if they justify the statements that Mr. McKenna has made, are absolutely untrue. They not only deceive the public, but from the persistence with which they are got up in the same sense, they must be intended to deceive the public."

Men's League for Women's Suffrage (18th November, 1910)

On this day in 1917 feminist Elizabeth Garrett Anderson died. Elizabeth, the daughter of Newson Garrett (1812–1893) and Louise Dunnell (1813–1903), was born in Whitechapel, London on 9th June 1836. Elizabeth's father, was the grandson of Richard Garrett, who founded the successful agricultural machinery works at Leiston.

Elizabeth's father had originally ran a pawnbroker's shop in London, but by the time she was born he owned a corn and coal warehouse in Aldeburgh, Suffolk. The business was a great success and by the 1850s Garrett could afford to send his children away to be educated.

After two years at a school in Blackheath, Elizabeth was expected to stay in the family home until she found a man to marry. However, Elizabeth was more interested in obtaining employment. While visiting a friend in London in 1854, Elizabeth met Emily Davies, a young women with strong opinions about women's rights. Davies introduced Elizabeth to other young feminists living in London.

In 1859 Garrett met Elizabeth Blackwell, the first woman in the United States to qualify as a doctor. Elizabeth decided she also wanted a career in medicine. Her parents were initially hostile to the idea but eventually her father, Newson Garrett, agreed to support her attempts to become Britain's first woman doctor.

Garrett tried to study in several medical schools but they all refused to accept a woman student. Garrett therefore became a nurse at Middlesex Hospital and attended lectures that were provided for the male doctors. After complaints from male students Elizabeth was forbidden entry to the lecture hall.

Garrett discovered that the Society of Apothecaries did not specify that females were banned for taking their examinations. In 1865 Garrett sat and passed the Apothecaries examination. As soon as Garrett was granted the certificate that enabled her to become a doctor, the Society of Apothecaries changed their regulations to stop other women from entering the profession in this way. With the financial support of her father, Elizabeth Garrett was able to establish a medical practice in London.

Elizabeth Garrett was now a committed feminist and in 1865 she joined with her friends Emily Davies, Barbara Bodichon, Bessie Rayner Parkes, Dorothea Beale and Francis Mary Buss to form a woman's discussion group called the Kensington Society. The following year the group organized a petition asking Parliament to grant women the vote.

Although Parliament rejected the petition, the women did receive support from Liberals such as John Stuart Mill and Henry Fawcett. Elizabeth became friendly with Fawcett, the blind MP for Brighton, but she rejected his marriage proposal, as she believed it would damage her career. Fawcett later married her younger sister Millicent Garrett.

In 1866 Garrett established a dispensary for women in London (later renamed the Elizabeth Garrett Anderson Hospital) and four years later was appointed a visiting physician to the East London Hospital. Elizabeth was determined to obtain a medical degree and after learning French, went to the University of Paris where she sat and passed the required examinations. However, the British Medical Register refused to recognize her MD degree.

During this period Elizabeth Garrett Anderson became involved in a dispute with Josephine Butler over the Contagious Diseases Acts. Josephine believed these acts discriminated against women and felt that all feminists should support their abolition. Garrett took the view that the measures provided the only means of protecting innocent women and children.

Although she was a supporter of the National Union of Women's Suffrage Societies (NUWSS) she was not an active member during this period. According to her daughter, Louisa Garrett Anderson, she thought "it would be unwise to be identified with a second unpopular cause. Nevertheless she gave her whole-hearted adherence."

The 1870 Education Act allowed women to vote and serve on School Boards. Garrett stood in London and won more votes than any other candidate. The following year she married James Skelton Anderson, a co-owner of the of the Orient Steamship Company, and the financial adviser to the East London Hospital.

Like other feminists at the time, Elizabeth Garrett retained her own surname. Although James Anderson supported Elizabeth's desire to continue as a doctor the couple became involved in a dispute when he tried to insist that he should take control of her earnings.

Elizabeth had three children, Louisa Garrett Anderson, Margaret who died of meningitis, and Alan. This did not stop her continuing her medical career and in 1872 she opened the New Hospital for Women in London, a hospital that was staffed entirely by women. Elizabeth Blackwell, the woman who inspired her to become a doctor, was appointed professor of gynecology.

Elizabeth Garrett Anderson also joined with Sophia Jex-Blake to establish a London Medical School for Women. Jex-Blake expected to put in charge but Garrett believed that her temperament made her unsuitable for the task and arranged for Isabel Thorne to be appointed instead. In 1883 Garrett Anderson was elected Dean of the London School of Medicine. Sophia Jex-Blake was the only member of the council who voted against this decision.

After the death of Lydia Becker in 1890, Elizabeth's sister, Millicent Garrett Fawcett was elected president of the National Union of Women's Suffrage Societies. By this time Elizabeth was a member of the Central Committee of the NUWSS.

In 1902 Garrett Anderson retired to Aldeburgh. Garrett Anderson continued her interest in politics and in 1908 she was elected mayor of the town - the first woman mayor in England. When Garret Anderson was seventy-two, she became a member of the militant Women's Social and Political Union. In 1908 was lucky not to be arrested after she joined with other members of the WSPU to storm the House of Commons. In October 1909 she went on a lecture tour with Annie Kenney.

However, Elizabeth left the WSPU's in 1911 as she objected to their arson campaign. Her daughter Louisa Garrett Anderson remained in the WSPU and in 1912 was sent to prison for her militant activities. Millicent Garrett Fawcett was upset when she heard the news and wrote to her sister: "I am in hopes she will take her punishment wisely, that the enforced solitude will help her to see more in focus than she always does." However, the authorities realised the dangers of her going on hunger strike and released her.

Evelyn Sharp spent time with Elizabeth and Louisa Garrett Anderson at their cottage in the Highlands: "Dr. Elizabeth Garrett Anderson, who had a summer cottage in that beautiful part of the Highlands. I went there on both occasions with her daughter Dr. Louisa Garrett Anderson, and we had great times together climbing the easier mountains and revelling in wonderful effects of colour that I have seen nowhere else except possibly in parts of Ireland.... It was, however, so entertaining to meet both these famous public characters in the more intimate and human surroundings of a summer holiday that we did not grudge the time given to working up a suffrage meeting in the village instead of tramping about the hills. Old Mrs. Garrett Anderson-old only in years, for there was never a younger woman in heart and mind and outlook than she was when I knew her before the war was a fascinating combination of the autocrat and the gracious woman of the world."

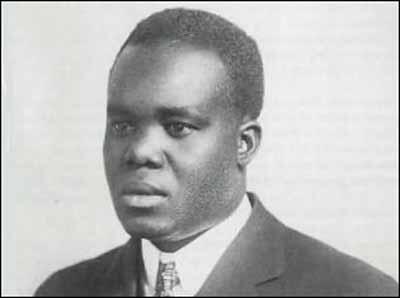

On this day in 1927 Hubert Harrison died. Harrison was born in St. Croix of the Virgin Islands in 1883. At the age of seventeen he travelled to New York City where he worked as a bellhop and an elevator operator. He also attended night school and studied sociology, science, psychology, literature, and drama.

Harrison's studies radicalized him and he became a member of the Industrial Workers of the World. He later joined the Socialist Party where he met other African American radicals such as Philip Randolph, Chandler Owen, and Claude McKay. He impressed them with his intellect and was given the nickname, the "Black Socrates". According to Barbara Bair, Harrison "protested the quick abandonment of the recruitment campaign among blacks in 1912... while openly criticizing the racial prejudice manifested by some party leaders."

Harrison joined Bill Haywood, Carlo Tresca, and Elizabeth Gurley Flynn in the Industrial Workers of the World campaign during the Paterson Silk Industry Strike in 1913. This alienated him from the executive committee of the Socialist Party. In 1914 he was suspended from the party.

Max Eastman, editor of the The Masses, employed him on his journal. Harrison also edited The Voice and contributed to the The Messenger, The Call, The New Republic, the New York Times and the New York World. He also published two important books, The Negro and the Nation (1917) and When Africa Awakes (1920).

Harrison was a strong opponent of United States involvement in the First World War. This caused him to break with William Du Bois who had argued in The Crisis that: "Let, us, while this war lasts, forget our special grievances and close our ranks."

Harrison also lectured on socialism and African American civil rights from street corners and in September, 1922, the New York Times reported that he was drawing crowds of over 10,000 people and the New York City police had to stop the traffic. His friend, Joel Rogers, recalled that "he spoke wherever an audience could be had on subjects embracing general literature, sociology, Negro history, and the leading events of the day."

It is claimed that Harrison had a great influence on Marcus Garvey. Harrison, who was now claiming that race was more important than class and after leaving the Socialist Party he joined Universal Negro Improvement Association (UNIA). Harrison also edited the organizations journal, The Negro World, for four years. He also worked as a staff lecturer for the New York City Board of Education.

Hubert Harrison advocated the creation of a separate black state within the territory of the United States, and in 1925 he founded the International Colored Unity League and a new periodical, the Voice of the Negro.

On this day in 1940 Franklin D. Roosevelt first tells the merican public about Lend-Lease in a radio broadcast "In the present world situation of course there is absolutely no doubt in the mind of a very overwhelming number of Americans that the best immediate defence of the United States is the success of Great Britain in defending itself; and that, therefore, quite aside from our historic and current interest in the survival of democracy in the world as a whole, it is equally important, from a selfish point of view of American defence, that we should do everything to help the British Empire to defend itself.

It isn't merely a question of doing things the traditional way; there are lots of other ways of doing them. I am just talking background, informally; I haven't prepared any of this - I go back to the idea that the one thing necessary for American national defence is additional productive facilities; and the more we increase those facilities - factories, shipbuilding ways, munition plants, et cetera, and so on - the stronger American national defence is.

I have been exploring other methods of continuing the building up of our productive facilities and continuing automatically the flow of munitions to Great Britain. I will just put it this way, not as an exclusive alternative method but as one of several other possible methods that might be devised toward that end.

It is possible - I will put it that way - for the United States to take over British orders and, because they are essentially the same kind of munitions that we use ourselves, turn them into American orders. We have enough money to do it. And there-upon, as to such portion of them as the military events of the future determine to be right and proper for us to allow to go to the other side, either lease or sell the materials, subject to mortgage, to the people on the other side. That would be on the general theory that it may still prove true that the best defence of Great Britain is the best defence of the United States, and therefore that these materials would be more useful to the defence of the United States if they were used in Great Britain than if they were kept in storage here.

Now, what I am trying to do is to eliminate the dollar sign. That is something brand new in the thoughts of practically everybody in this room, I think - get rid of the silly, foolish old dollar sign. Well, let me give you an illustration: Suppose my neighbor's home catches fire, and I have a length of garden hose 400 or 500 feet away. If he can take my garden hose and connect it up with his hydrant, I may help him to put out his fire. Now, what do I do? I don't say to him before that operation, "Neighbor, my garden hose cost me $15; you have to pay me $15 for it." What is the transaction that goes on? I don't want $15 - I want my garden hose back after the fire is over. All right. If it goes through the fire all right, intact, without any damage to it, he gives it back to me and thanks me very much for the use of it. But suppose it gets smashed up - holes in it - during the fire; we don't have to have too much formality about it, but I say to him, "I was glad to lend you that hose; I see I can't use it any more, it's all smashed up." He says, "How many feet of it were there?" I tell him, "There were 150 feet of it." He says, "All right, I will replace it." Now, if I get a nice garden hose back, I am in pretty good shape.

In other words, if you lend certain munitions and get the munitions back at the end of the war, if they are intact - haven't been hurt - you are all right; if they have been damaged or have deteriorated or have been lost completely, it seems to me you come out pretty well if you have them replaced by the fellow to whom you have lent them.

I can't go into details; and there is no use asking legal questions about how you would do it, because that is the thing that is now under study; but the thought is that we would take over not all, but a very large number of, future British orders; and when they came off the line, whether they were planes or guns or something else, we would enter into some kind of arrangement for their use by the British on the ground that it was the best thing for American defence, with the understanding that when the show was over, we would get repaid sometime in kind, thereby leaving out the dollar mark in the form of a dollar debt and substituting for it a gentleman's obligation to repay in kind. I think you all get it."

On this day in 1943 Robert Blatchford died. Robert Blatchford, the son of an actor, was born in Maidstone in 1851. Robert father died when he was two and at the age of fourteen he was apprenticed as a brushmaker. He disliked the work and ran away to join the army.

Blatchford reached the rank of sergeant major before leaving the service in 1878. After trying a variety of different jobs he became a freelance journalist. After working for several newspapers he became leader writer for the Sunday Chronicle in Manchester. It was his journalistic experience of working-class life that turned Blatchford into a socialist.

In 1890 Blatchford founded the Manchester Fabian Society. The following year, Blatchford and four fellow members launched a socialist newspaper, The Clarion. Blatchford, who was editor, announced that the newspaper would follow a "policy of humanity; a policy not of party, sect or creed; but of justice, of reason and mercy." The first edition sold 40,000 and after a few months settled down to about 30,000 copies a week.

It was decided in 1893 to publish some of Blatchford's articles about socialism as a book. Merrie England, was an immediate success, with the cheap edition selling over 2,000,000 copies. Influenced by the ideas of William Morris, Blatchford emphasized the importance of the arts and the values of the countryside. Considered to be an excellent example of socialist propaganda, the book was translated into several different languages.

Robert Blatchford upset many of his socialist supporters by his nationalistic views on foreign policy. He supported the government during the Boer War and warned against what he saw was the German menace. Blatchford also changed his views on equal rights and strongly opposed the policies of the NUWSS and the WSPU.

After the First World War Blatchford moved to the right and became a passionate advocate of the British Empire. In the 1924 General Election he supported the Conservative Party and declared that Stanley Baldwin was Britain's finest politician.

On this day in 2005 journalist Jack Anderson died. Anderson was born in Long Beach, California, on 19th October, 1922. Two years later his family moved to Utah, the stronghold of the Mormon Church. Anderson was brought up in Salt Lake City and his journalistic career started at school when he began writing for his local newspaper, The Murray Eagle. At eighteen he joined the Salt Lake Tribune but left the job to become a Mormon missionary in the Deep South.

In 1943 Anderson he enrolled in the Merchant Marine officers training school. After seven months he persuaded the Desert News to accredit him as a foreign correspondent in China. Acccording to Anderson he was supposed to write "stories about hometown heroes gone to war". He disliked this work and managed to get involved with the Office of Strategic Services (OSS). The OSS sent Anderson to contact a band of Chinese Nationalist guerrillas fighting the Japanese Army. Soon afterwards Anderson met Chou En-lai and wrote about his activities for the Associated Press.

Others working in China at the time included Ray S. Cline, Richard Helms, E. Howard Hunt, Jake Esterline, Mitchell WerBell, John Singlaub, Paul Helliwell, Jack Anderson, Robert Emmett Johnson, Jack Hawkins, Lucien Conein, Philip Graham, Tommy Corcoran, Whiting Willauer and William Pawley. These men were later to become very important to Anderson in his journalistic career.

In 1945 Anderson joined the United States Army in Chunking. He first served in the Quartermaster Corps and then wrote for the Stars and Stripes. He also did some reporting for the Armed Forces Radio. According to Anderson's autobiography, Confessions of a Muckraker (1979), Spencer Moosa of the Associated Press suggested to Anderson that he should try and get a job with Drew Pearson in Washington.

Anderson took Moosa's advice and in 1947 he became a member of Pearson's staff. Anderson was a "legman" for Pearson's column, Merry-Go-Round, that appeared in the Washington Post and in newspapers all over the United States. One of Anderson's first stories concerned the dispute between Howard Hughes, the owner of Trans World Airlines, and Owen Brewster, chairman of the Senate War Investigating Committee. Hughes claimed that Brewster was being paid by Pan American Airways (Pan Am) to persuade the United States government to set up an official worldwide monopoly under its control. Part of this plan was to force all existing American carriers with overseas operations to close down or merge with Pan Am. As the owner of Trans World Airlines, Hughes posed a serious threat to this plan. Hughes claimed that Brewster had approached him and suggested he merge Trans World with Pan Am. Pearson and Anderson began a campaign against Brewster. They reported that Pan Am had provided Bewster with free flights to Hobe Sound, Florida, where he stayed free of charge at the holiday home of Pan Am Vice President Sam Pryor. As a result of this campaign Bewster lost his seat in Congress.

In the late 1940s Anderson became friendly with Joseph McCarthy. As he pointed out in his autobiography, Confessions of a Muckraker, "Joe McCarthy... was a pal of mine, irresponsible to be sure, but a fellow bachelor of vast amiability and an excellent source of inside dope on the Hill." McCarthy began supplying Anderson with stories about suspected communists in government. Drew Pearson refused to publish these stories as he was very suspicious of the motives of people like McCarthy. In fact, in 1948, Pearson began investigating J. Parnell Thomas, the Chairman of the House of Un-American Activities Committee. It was not long before Thomas' secretary, Helen Campbell, began providing information about his illegal activities.

On 4th August, 1948, Pearson published the story that Thomas had been putting friends on his congressional payroll. They did no work but in return shared their salaries with Thomas. Called before a grand jury, Thomas availed himself to the 1st Amendment, a strategy that he had been unwilling to accept when dealing with the Hollywood Ten. Indicted on charges of conspiracy to defraud the government, Thomas was found guilty and sentenced to 18 months in prison and forced to pay a $10,000 fine. Two of his fellow inmates in Danbury Prison were Lester Cole and Ring Lardner Jr who were serving terms as a result of refusing to testify in front of Thomas and the House of Un-American Activities Committee.

In 1949 Drew Pearson criticised the Secretary of Defence, James Forrestal, for his conservative views on foreign policy. He told Jack Anderson that he believed Forrestal was "the most dangerous man in America" and claimed that if he was not removed from office he would "cause another world war". Pearson also suggested that Forrestal was guilty of corruption. Pearson was blamed when Forrestal committed suicide on 22nd May 1949. One journalist, Westbrook Pegler, wrote: "For months, Drew Pearson... hounded Jim Forrestal with dirty aspersions and insinuations, until, at last, exhausted and his nerves unstrung, one of the finest servants that the Republic ever had died of suicide."

Anderson and Pearson also began investigating General Douglas MacArthur. In December, 1949, Anderson got hold of a top-secret cable from MacArthur to the Joint Chiefs of Staff, expressing his disagreement with President Harry S. Truman concerning Chaing Kai-shek. On 22nd December, 1949, Pearson published the story that: "General MacArthur has sent a triple-urgent cable urging that Formosa be occupied by U.S. troops." Pearson argued that MacArthur was "trying to dictate U.S. foreign policy in the Far East".

President Truman and Dean Acheson, the Secretary of State, told MacArthur to limit the war to Korea. MacArthur disagreed, favoring an attack on Chinese forces. Unwilling to accept the views of Truman and Dean Acheson, MacArthur began to make inflammatory statements indicating his disagreements with the United States government.

MacArthur gained support from right-wing members of the Senate such as Joe McCarthy who led the attack on Truman's administration: "With half a million Communists in Korea killing American men, Acheson says, "Now let's be calm, let's do nothing. It is like advising a man whose family is being killed not to take hasty action for fear he might alienate the affection of the murders."

On 7th October, 1950, MacArthur launched an invasion of North Korea and by the end of the month had reached the Yalu River, close to the frontier of China. On 20th November, Pearson wrote in his column that the Chinese was "sucking our troops into a trap." Three days later the Chinese Army launched an attack on MacArthur's army. North Korean forces took Seoul in January 1951. Two months later, Harry S. Truman removed MacArthur from his command of the United Nations forces in Korea.

Joe McCarthy continued to provide Anderson with a lot of information. In his autobiography, Confessions of a Muckraker, Anderson pointed out: "At my prompting he (McCarthy) would phone fellow senators to ask what had transpired this morning behind closed doors or what strategy was planned for the morrow. While I listened in on an extension he would pump even a Robert Taft or a William Knowland with the handwritten questions I passed him." In return, Anderson provided McCarthy with information about politicians and state officials he suspected of being "communists". Anderson later recalled that his decision to work with McCarthy "was almost automatic.. for one thing, I owed him; for another, he might be able to flesh out some of our inconclusive material, and if so, I would no doubt get the scoop." As a result Anderson passed on his file on the presidential aide, David Demarest Lloyd.

On 9th February, 1950, McCarthy made a speech in Salt Lake City where he attacked Dean Acheson, the Secretary of State, as "a pompous diplomat in striped pants". He claimed that he had a list of 57 people in the State Department that were known to be members of the American Communist Party. McCarthy went on to argue that some of these people were passing secret information to the Soviet Union. He added: "The reason why we find ourselves in a position of impotency is not because the enemy has sent men to invade our shores, but rather because of the traitorous actions of those who have had all the benefits that the wealthiest nation on earth has had to offer - the finest homes, the finest college educations, and the finest jobs in Government we can give."

The list of names was not a secret and had been in fact published by the Secretary of State in 1946. These people had been identified during a preliminary screening of 3,000 federal employees. Some had been communists but others had been fascists, alcoholics and sexual deviants. As it happens, if Joe McCarthy had been screened, his own drink problems and sexual preferences would have resulted in him being put on the list.

Drew Pearson immediately launched an attack on McCarthy. He pointed out that only three people on the list were State Department officials. He added that when this list was first published four years ago, Gustavo Duran and Mary Jane Keeney had both resigned from the State Department (1946). The third person, John S. Service, had been cleared after a prolonged and careful investigation. Pearson also argued that none of these people had been members of the American Communist Party.

Jack Anderson asked Pearson to stop attacking McCarthy: "He is our best source on the Hill." Pearson replied, "He may be a good source, Jack, but he's a bad man." On 20th February, 1950, McCarthy made a speech in the Senate supporting the allegations he had made in Salt Lake City. This time he did not describe them as "card-carrying communists" because this had been shown to be untrue. Instead he argued that his list were all "loyalty risks". He also claimed that one of the president's speech-writers, was a communist. Although he did not name him, he was referring to David Demarest Lloyd, the man that Anderson had provided information on. Lloyd immediately issued a statement where he defended himself against McCarthy's charges. President Harry S. Truman not only kept him on but promoted him to the post of Administrative Assistant. Lloyd was indeed innocent of these claims and McCarthy was forced to withdraw these allegations. As Anderson admitted: "At my instigation, then, Lloyd had been done an injustice that was saved from being grevious only by Truman's steadfastness."

McCarthy now informed Anderson that he had evidence that Professor Owen Lattimore, director of the Walter Hines Page School of International Relations at Johns Hopkins University, was a Soviet spy. Pearson, who knew Lattimore, and while accepting he held left-wing views, he was convinced he was not a spy. In his speeches, McCarthy referred to Lattimore as "Mr X... the top Russian spy... the key man in a Russian espionage ring." On 26th March, 1950, Drew Pearson named Lattimore as McCarthy's Mr. X. Pearson then went onto defend Lattimore against these charges. McCarthy responded by making a speech in Congress where he admitted: "I fear that in the case of Lattimore I may have perhaps placed too much stress on the question of whether he is a paid espionage agent."

McCarthy then produced Louis Budenz, the former editor of The Daily Worker. Budenz claimed that Lattimore was a "concealed communist". However, as Anderson admitted: "Budenz had never met Lattimore; he spoke not from personal observation of him but from what he remembered of what others had told him five, six, seven and thirteen years before."

Pearson now wrote an article where he showed that Budenz was a serial liar: "Apologists for Budenz minimize this on the ground that Budenz has now reformed. Nevertheless, untruthful statements made regarding his past and refusal to answer questions have a bearing on Budenz's credibility." He went on to point out that "all in all, Budenz refused to answer 23 questions on the ground of self-incrimination". Owen Lattimore was eventually cleared of the charge that he was a Soviet spy or a secret member of the American Communist Party and like other victims of McCarthyism, he went to live in Europe and for several years was professor of Chinese studies at Leeds University.

Despite the efforts of Jack Anderson, by the end of June, 1950, Drew Pearson had written more than forty daily columns and a significant percentage of his weekly radio broadcasts, that had been devoted to discrediting the charges made by Joe McCarthy. As a result, McCarthy decided to take on Pearson. McCarthy told Anderson: "Jack, I'm going to have to go after your boss. I mean, no holds barred. I figure I've already lost his supporters; by going after him, I can pick up his enemies." McCarthy, when drunk, told Assistant Attorney General Joe Keenan, that he was considering "bumping Pearson off". On 15th December, 1950, McCarthy made a speech in Congress where he claimed that Pearson was "the voice of international Communism" and "a Moscow-directed character assassin." McCarthy added that Pearson was "a prostitute of journalism" and that Pearson "and the Communist Party murdered James Forrestal in just as cold blood as though they had machine-gunned him."

Over the next two months McCarthy made seven Senate speeches on Drew Pearson. He called for a "patriotic boycott" of his radio show and as a result, Adam Hats, withdrew as Pearson's radio sponsor. Although he was able to make a series of short-term arrangements, Pearson was never again able to find a permanent sponsor. Twelve newspapers cancelled their contract with Pearson.

Joe McCarthy and his friends also raised money to help Fred Napoleon Howser, the Attorney General of California, to sue Pearson for $350,000. This involved an incident in 1948 when Pearson accused Howser of consorting with mobsters and of taking a bribe from gambling interests. Help was also given to Father Charles Coughlin, who sued Pearson for $225,000. However, in 1951 the courts ruled that Pearson had not libeled either Howser or Coughlin. Only the St. Louis Star-Times defended Pearson. As its editorial pointed out: "If Joseph McCarthy can silence a critic named Drew Pearson, simply by smearing him with the brush of Communist association, he can silence any other critic." However, Pearson did get the support of J. William Fulbright, Wayne Morse, Clinton Anderson, William Benton and Thomas Hennings in the Senate.

After his attack on Drew Pearson, Anderson had no choice but to abandoned Joe McCarthy. He now joined forces with Wisconsin reporter Ronald W. May to write McCarthy: The Man, the Senator, the Ism (1952). In October, 1953, Joe McCarthy began investigating communist infiltration into the military. Attempts were made by McCarthy to discredit Robert Stevens, the Secretary of the Army. The president, Dwight Eisenhower, was furious and now realised that it was time to bring an end to McCarthy's activities.

The United States Army now passed information about McCarthy to journalists who were known to be opposed to him. This included the news that Joe McCarthy and Roy Cohn had abused congressional privilege by trying to prevent David Schine from being drafted. When that failed, it was claimed that Cohn tried to pressurize the Army into granting Schine special privileges. Drew Pearson published the story on 15th December, 1953.

Some figures in the media, such as writers George Seldes and I. F. Stone, and cartoonists, Herb Block and Daniel Fitzpatrick, had fought a long campaign against McCarthy. Other figures in the media, who had for a long time been opposed to McCarthyism, but were frightened to speak out, now began to get the confidence to join the counter-attack. Edward Murrow, the experienced broadcaster, used his television programme, See It Now, on 9th March, 1954, to criticize McCarthy's methods. Newspaper columnists such as Walter Lippmann also became more open in their attacks on McCarthy.The senate investigations into the United States Army were televised and this helped to expose the tactics of Joseph McCarthy. One newspaper, the Louisville Courier-Journal, reported that: "In this long, degrading travesty of the democratic process, McCarthy has shown himself to be evil and unmatched in malice." Leading politicians in both parties, had been embarrassed by McCarthy's performance and on 2nd December, 1954, a censure motion condemned his conduct by 67 votes to 22.

McCarthy also lost the chairmanship of the Government Committee on Operations of the Senate. He was now without a power base and the media lost interest in his claims of a communist conspiracy. As one journalist, Willard Edwards, pointed out: "Most reporters just refused to file McCarthy stories. And most papers would not have printed them anyway."

Anderson helped Pearson investigate stories of corruption inside the administration of President Dwight Eisenhower. They discovered that Eisenhower had received gifts worth more than $500,000 from "big-business well-wishers." Anderson was a close friend of Lyndon B. Johnson. In 1956 Pearson began investigating the relationship between Johnson and two businessmen, George R. Brown and Herman Brown from Texas. Pearson believed that Johnson had arranged for the Texas-based Brown and Root Construction Company to avoid large tax bills. Johnson brought an end to this investigation by offering Pearson a deal. If Pearson dropped his Brown-Root crusade, Johnson would support the presidential ambitions of Estes Kefauver. Pearson accepted and wrote in his diary (16th April, 1956): "This is the first time I've ever made a deal like this, and I feel a little unhappy about it. With the Presidency of the United States at stake, maybe it's justified, maybe not - I don't know."

In 1957 Anderson threaten to quit as Pearson's assistant. He complained that his stories always appeared under Pearson's name. Pearson responded by promising him more bylines and pledged to leave the column to him when he died. Anderson agreed to do the deal and continued work for him. Jack Anderson's next assignment was the investigation of the presidential assistant Sherman Adams. The former governor of New Hampshire, was considered to be a key figure in Eisenhower's administration. Anderson discovered that Bernard Goldfine, a wealthy industrialist, had given Adams a large number of presents. This included suits, overcoats, alcohol, furnishings and the payment of hotel and resort bills. Anderson eventually found evidence that Adams had twice persuaded the Federal Trade Commission to "ease up its pursuit of Goldfine for putting false labels on the products of his textile plants."The story was eventually published in 1958 and Adams was forced to resign from office. However, Anderson was much criticized for the way he carried out his investigation and one of his assistants, Les Whitten, was arrested by the FBI for receiving stolen government documents.

In 1960 Drew Pearson supported Hubert Humphrey in his efforts to become the Democratic Party candidate. However, those campaigning for John F. Kennedy, accused him of being a draft dodger. As a result, when Humphrey dropped out of the race, Anderson persuaded Pearson to switch his support to Lyndon B. Johnson. However, it was Kennedy who eventually got the nomination. Anderson and Pearson now supported Kennedy.

One of the ways they helped Kennedy's campaign was to investigate the relationship between Howard Hughes and Richard Nixon. Pearson and Anderson discovered that in 1956 the Hughes Tool Company provided a $205,000 loan to Nixon Incorporated, a company run by Richard's brother, F. Donald Nixon. The money was never paid back. Soon after the money was paid the Internal Revenue Service (IRS) reversed a previous decision to grant tax-exempt status to the Howard Hughes Medical Institute. This information was revealed by Anderson and Pearson during the 1960 presidential campaign. Nixon initially denied the loan but later was forced to admit that this money had been given to his brother. It was claimed that this story helped Kennedy defeat Nixon in the election.

In 1963 Senator John Williams of Delaware began investigating the activities of Bobby Baker. As a result of his work, Baker resigned as the secretary to Lyndon B. Johnson on 9th October, 1963. During his investigations Williams met Don B. Reynolds and persuaded him to appear before a secret session of the Senate Rules Committee. Reynolds told B. Everett Jordan and his committee on 22nd November, 1963, that Johnson had demanded that he provided kickbacks in return for him agreeing to this life insurance policy. This included a $585 Magnavox stereo. Reynolds also had to pay for $1,200 worth of advertising on KTBC, Johnson's television station in Austin. Reynolds had paperwork for this transaction including a delivery note that indicated the stereo had been sent to the home of Johnson. Reynolds also told of seeing a suitcase full of money which Bobby Baker described as a "$100,000 payoff to Johnson for his role in securing the Fort Worth TFX contract". His testimony came to an end when news arrived that President John F. Kennedy had been assassinated.

As soon as Johnson became president he contacted B. Everett Jordan to see if there was any chance of stopping this information being published. Jordan replied that he would do what he could but warned Johnson that some members of the committee wanted Reynold's testimony to be released to the public. On 6th December, 1963, Jordan spoke to Johnson on the telephone and said he was doing what he could to suppress the story because " it might spread (to) a place where we don't want it spread."

Abe Fortas, a lawyer who represented both Lyndon B. Johnson and Bobby Baker, worked behind the scenes in an effort to keep this information from the public. Johnson also arranged for a smear campaign to be organized against Reynolds. To help him do this J. Edgar Hoover passed to Johnson the FBI file on Reynolds. On 17th January, 1964, the Senate Rules Committee voted to release to the public Reynolds' secret testimony. Johnson responded by leaking information from Reynolds' FBI file to Anderson. On 5th February, 1964, the Washington Post reported that Reynolds had lied about his academic success at West Point. The article also claimed that Reynolds had been a supporter of Joseph McCarthy and had accused business rivals of being secret members of the American Communist Party. It was also revealed that Reynolds had made anti-Semitic remarks while in Berlin in 1953.

Like other political journalists, Anderson and Drew Pearson investigated the death of John F. Kennedy. Sources close to John McCone and Robert Kennedy claimed that the assassination was linked to the plots against Fidel Castro of Cuba.

In 1965, Jack Anderson achieved full partnership in the Merry-Go-Round column and now sharing a byline with Drew Pearson. However, Anderson still complained about the relationship because he was only paid $15,000 a year. Anderson returned to the investigation of the assassination of John F. Kennedy in 1966. At the time attempts were made to deport Johnny Roselli as an illegal alien. Roselli moved to Los Angeles where he went into early retirement. It was at this time he told attorney, Edward Morgan: "The last of the sniper teams dispatched by Robert Kennedy in 1963 to assassinate Fidel Castro were captured in Havana. Under torture they broke and confessed to being sponsored by the CIA and the US government. At that point, Castro remarked that, 'If that was the way President Kennedy wanted it, Cuba could engage in the same tactics'. The result was that Castro infiltrated teams of snipers into the US to kill Kennedy".

Morgan took the story to Jack Anderson and Drew Pearson. The story was then passed on to Earl Warren. He did not want anything to do with it and so the information was then passed to the FBI. When they failed to investigate the story Anderson wrote an article entitled "President Johnson is sitting on a political H-bomb" about Roselli's story. It has been suggested that Roselli started this story at the request of his friends in the Central Intelligence Agency in order to divert attention from the investigation being carried out by Jim Garrison.

In 1968 Jack Anderson and Drew Pearson published The Case Against Congress. The book documented examples of how politicians had "abused their power and priviledge by placing their own interests ahead of those of the American people". This included the activities of Bobby Baker, James Eastland, Lyndon B. Johnson, Dwight Eisenhower, Hubert Humphrey, Everett Dirksen, Thomas J. Dodd, John McClellan and Clark Clifford.

On the death of Drew Pearson in 1969, Anderson took over his Merry-Go-Round column. Co-written with Jan Muller, the column was distributed to more than 400 newspapers. Anderson and Muller also wrote the Jack Anderson Confidential, an in-depth monthly newsletter.

Anderson has achieved many important stories including the discovery that Central Intelligence Agency plot to kill Fidel Castro. In 1972 Anderson won the Pulitzer Prize for journalism. This was for his reports claiming that the Nixon administration secretly tilted toward Pakistan in its war with India. The following year his book, The Anderson Tapes, dealt with the activities of Richard Nixon and J. Edgar Hoover.

Anderson interviewed Johnny Roselli just before he was murdered. On 7th September, 1976, Anderson reported Roselli as saying : "When Oswald was picked up, the underworld conspirators feared he would crack and disclose information that might lead to them. This almost certainly would have brought a massive U.S. crackdown on the Mafia. So Jack Ruby was ordered to eliminate Oswald."

Anderson's autobiography, Confessions of a Muckraker, was published in 1979. Anderson also investigated the Watergate Scandal. It was later discovered that Jeb Magruder and G. Gordon Liddy discussed the possibility of having Anderson added to a hit list. Anderson pointed out in Peace, War and Politics: An Eyewitness Account (1999) that Liddy was under the impression that "Richard Nixon wanted me dead".

Mark Feldstein, director of the journalism program at George Washington University, has argued: "Part circus huckster, part guerrilla fighter, part righteous rogue, Anderson waged a one-man journalistic resistance when it was exceedingly unpopular to do so." Douglas Martin of the New York Times, commented: "His bombastic, self-congratulating style, abbreviated exegeses and a blistering moral outrage fueled both by his Mormon upbringing and unabashed theatrical flair caused some to question his gravity." Anderson defended his work in an article in The Washington Post in 1983: "I have to do daily what Woodward and Bernstein did once" it is a column of "tweaks, leaks and piques, born of idealism, stoked by cynicism, a brazen, high-risk, righteously indignant antiwaste, anticorruption, anticommunist watchdog of a column that has been called everything from 'gold' to 'garbage.' Sometimes on the same day. Sometimes in the same sentence."

In 1989 Anderson received information from Joseph Shimon, that he had been at meetings with Sam Giancana and Santo Trafficante where they discussed plans to assassinate Fidel Castro. All these plots failed and Shimon became convinced that Trafficante was working for Castro. This story eventually appeared in the Merry-Go-Round column.

In 1992 Anderson was working on a television project on the Exxon Valdez oil spill. However, he was eventually forced to withdraw from the project when it was revealled that Anderson had received $10,000 from Exxon to make the program. Other books by Anderson include The Washington Money-Go-Round (1997) and Peace, War and Politics: An Eyewitness Account (1999).

Jack Anderson retired from journalism in July, 2004. He died at his home in Bethesda, Maryland, of complications from Parkinson's disease, on 17th December, 2005.