On this day on 14th April

On this day in 1865 President Abraham Lincoln is shot in Ford's Theatre by John Wilkes Booth. Booth was born in Bel Air, Maryland, on 10th May, 1838. He was the ninth of ten children born to the famous actor, Junius Brutus Booth. Booth made his acting debut at the age of seventeen in Baltimore. He toured throughout America and soon became one of America's leading actors and was especially acclaimed for the work he did with the Shakespearean company that was based in Richmond.

Unlike the rest of his family, Booth was an ardent supporter of slavery. In 1859 he joined the Virginia militia company that assisted in the capture of John Brown at Harper's Ferry.

Although Booth had a deep hatred for President Lincoln and the Republican Party, he did not join the Confederate Army on the outbreak of the American Civil War. Instead he worked as a secret agent and also helped to smuggle medical supplies from the North to the Confederate forces in the South. As a touring actor Booth had the perfect cover for this work.

In 1864 Booth devised a scheme to kidnap Abraham Lincoln in Washington. The plan was to take Lincoln to Richmond and hold him until he could be exchanged for Confederate Army prisoners of war. Others involved in the plot included Lewis Powell, George Atzerodt, John Surratt, David Herold, Michael O'Laughlin and Samuel Arnold. Booth decided to carry out the deed on 17th March, 1865 when Lincoln was planning to attend a play at the Seventh Street Hospital that was situated on the outskirts of Washington. The kidnap attempt was abandoned when Lincoln decided at the last moment to cancel his visit.

On 9th April, 1865, General Robert E. Lee surrendered to General Ulysses S. Grant at Appomattox. Two days later Booth attended a public meeting in Washington where he heard Abraham Lincoln make a speech where he explained his views that voting rights should be granted to some African Americans. Booth was furious and decided to assassinate the president before he could carry out these plans.

Booth persuaded most of the people who had been involved in the kidnap plot to join him in his plan. Booth discovered that on 14th April, Abraham Lincoln was planning to attend the evening performance of Our American Cousin at the Ford Theatre in Washington. Booth decided he would assassinate Lincoln while George Atzerodt and Lewis Powell would kill Vice President Andrew Johnson and Secretary of State William Seward. All attacks would take place at approximately 10.15 p.m. that night.

Booth, armed with a derringer pistol and a hunting knife, arrived at the theatre at about 9.30 p.m. John Burroughs, a boy who worked at the theatre, was asked to hold his horse while he went to a nearby saloon for a drink. He entered Ford's Theatre soon after 10.00 p.m. and made his way to the State Box. John Parker, Lincoln's bodyguard from the Metropolitan Police Force, had left his position outside the State Box to get a drink. Inside was Abraham Lincoln, his wife Mary Lincoln, and two friends, Major Henry Rathbone and his future wife, Clara Harris.

At 10.15 p.m. Booth entered the State Box and shot Abraham Lincoln in the back of the head. When Rathbone attempted to grab Booth he was slashed with the hunting knife. Booth then jumped about 11 feet onto the stage below. He landed badly and snapped the fibula bone in his left leg just above the ankle. Booth waving his hunting knife at the audience, hobbled outside and got on his horse and rode out of the city.

Meanwhile Lewis Powell had attacked William Seward in his house. Although badly wounded, he survived. George Atzerodt, lost his nerve, and never made his assassination attempt on Andrew Johnson. The plan was for the conspirators to meet at the boarding house owned by Mary Surratt in Surrattsville, Maryland. After a brief stop to pick up supplies Booth and David Herold left and headed for the Deep South.

At 4.00 a.m. Booth and Herold arrived at the home of Dr. Samuel Mudd who treated Booth's broken leg. With the help of other sympathizers they reached Port Royal, Virginia, on the morning of 26th April. They hid in a barn owned by Richard Garrett. However, federal troops arrived soon afterwards and the men were ordered to surrender.

David Herold came out of the barn but Booth refused and so the barn was set on fire. While this was happening one of the soldiers, Sergeant Boston Corbett, found a large crack in the barn and was able to shoot Booth in the back. His body was dragged from the barn and after being searched the soldiers recovered his leather bound diary. The bullet had punctured his spinal cord and he died in great agony two hours later.

On 29th June, 1865 Mary Surratt, Lewis Powell, George Atzerodt, David Herold, Samuel Mudd, Michael O'Laughlin, Edman Spangler and Samuel Arnold were found guilty of being involved in the conspiracy to murder Lincoln. Surratt, Powell, Atzerodt and Herold were hanged at Washington Penitentiary on 7th July, 1865. Surratt, who was expected to be reprieved, was the first woman in American history to be executed.

On this day in 1866 Helen Keller's teacher, Anne Sullivan, was born. Helen Keller was born in Tuscumbia, Alabama on 27th June, 1880. Her father, Arthur H. Keller, was the editor for the North Alabamian, and had fought in the Confederate Army during the American Civil War. At 19 months she suffered "an acute congestion of the stomach and brain (probably scarlet fever) which left her deaf and blind.

She later wrote in The Story of My Life: "In the dreary month of February, came the illness which closed my eyes and ears and plunged me into the unconsciousness of a new born baby. They called it acute congestion of the stomach and brain. The doctor thought I could not live. Early one morning, however, the fever left me as suddenly and mysteriously as it had come. There was great rejoicing in the family that morning, but no one not even the doctor, knew that I should never see or hear again." As a child she was taken to see Alexander G. Bell. He suggested that the family should contact the Perkins Institute for the Blind in Boston.

In 1886 the Perkins Institute provided Keller with the teacher Anne Sullivan. She later recalled: "We walked down the path to the well-house, attracted by the fragrance of the honeysuckle with which it was covered. Some one was drawing water and my teacher placed my hand under the spout. As the cool stream gushed over one hand she spelled into the other the word water, first slowly, then rapidly. I stood still, my whole attention fixed upon the motions of her fingers. Suddenly I felt a misty consciousness as of something forgotten - a thrill of returning thought; and somehow the mystery of language was revealed to me. I knew then that "w-a-t-e-r" meant the wonderful cool something that was flowing over my hand. That living word awakened my soul, gave it light, hope, joy, set it free! There were barriers still, it is true, but barriers that could in time be swept away." The 21 year old Sullivan worked out an alphabet by which she spelled out words on Helen's hand. Gradually Keller was able to connect words with objects.

Sullivan's teaching skills and Keller's abilities, enabled her at the age of 16 to pass the admissions examinations for Radcliffe College. While at college she wrote the first volume of her autobiography, The Story of My Life. It was published serially in the Ladies' Home Journal and, in 1902, as a book. By the time she had graduated in 1904 she had mastered five languages.

While at college she developed a strong interest in women's rights and became a militant campaigner in favour of universal suffrage. She also became friends with several notable public figures including John Greenleaf Whittier, Oliver Wendell Holmes and William Dean Howells. The journalist, Max Eastman, became a friend during this period. He later recalled: "The gleam of true, courageous and unaffected joy in living that shone out of her gray-blue eyes. Her face was round; she was a round-limbed girl, perpetually young in her bearing, as though her limitations had made it easy instead of hard to grow older."

Keller's political views were influenced by conversations she had with John Macy (Anne Sullivan's husband) and reading New Worlds for Old by H. G. Wells. In 1909 Keller became a socialist and was active in various campaigns including those in favour of birth control, trade unionism and against child labour and capital punishment.

Keller was a supporter of Emmeline Pankhurst and the militant Women's Social and Political Union in Britain. She told the New York Times: "I believe the women of England are doing right. Mrs Pankhurst is a great leader. The women of America should follow her example. They would get the ballot much faster if they did. They cannot hope to get anything unless they are willing to fight and suffer for it.

In 1912 Keller was interviewed by Ernest Gruening, a young journalist working for the Boston American. He later wrote about it in his autobiography, Many Battles (1973): "She had never before been interviewed for publication, so I communicated with her teacher-companion, Anne Sullivan Macy, and on securing assent went to their home in Wrentham... Helen Keller who, besides being deaf since infancy, was also blind. Miss Keller's voice was high-pitched with a peculiar metallic ring, but her speech was remarkably clear.... Miss Keller came out of the porch to greet me and, asking me to sit beside her, told me to put the fore and middle fingers on her right hand on my lips. By that means she could understand everything I said. She spoke with enthusiasm of her aspirations to help others who were deaf and blind, and revealed that she was a socialist, repeatedly referring to socialism as the cure for the nation's ills."

Keller joined the Socialist Party of America and campaigned for Eugene Debs and his running-mate, Emil Seidel, in the 1912 Presidential Election. During the campaign Debs explained why people should vote for him: "You must either vote for or against your own material interests as a wealth producer; there is no political purgatory in this nation of ours, despite the desperate efforts of so-called Progressive capitalists politicians to establish one. Socialism alone represents the material heaven of plenty for those who toil and the Socialist Party alone offers the political means for attaining that heaven of economic plenty which the toil of the workers of the world provides in unceasing and measureless flow. Capitalism represents the material hell of want and pinching poverty of degradation and prostitution for those who toil and in which you now exist, and each and every political party, other than the Socialist Party, stands for the perpetuation of the economic hell of capitalism." Debs and Seidel won 901,551 votes (6.0%). This was the most impressive showing of any socialist candidate in the history of the United States.

A book on Keller's socialist views, Out of the Dark, was published in 1913. She later wrote "I had once believed that we are all masters of our fate - that we could mould our lives into any form we pleased. I had overcome deafness and blindness sufficiently to be happy, and I supposed that anyone could come out victorious if he threw himself valiantly into life's struggle. But as I went more and more about the country I learned that I had spoken with assurance on a subject I knew little about. I forgot that I owed my success partly to the advantages of my birth and environment. Now, however, I learned that the power to rise in the world is not within the reach of everyone." Hattie Schlossberg wrote in the New York Call: "Helen Keller is our comrade, and her socialism is a living vital thing for her. All her speeches are permeated with the spirit of socialism."

In 1912 Keller joined the theIndustrial Workers of the World (IWW). A socialist trade union group that opposed the policies of American Federation of Labour. Keller wrote later: "Surely the demands of the IWW are just. It is right that the creators of wealth should own what they create. When shall we learn that we are related one to the other; that we are members of one body; that injury to one is injury to all? Until the spirit of love for our fellow-workers, regardless of race, color, creed or sex, shall fill the world, until the great mass of the people shall be filled with a sense of responsibility for each other’s welfare, social justice cannot be attained, and there can never be lasting peace upon earth."

Keller also wrote articles for the socialist journal, The Masses. Keller, a pacifist, believed that the First World War had been caused by the imperialist competitive system and that the USA should remain neutral. After the USA declared war on the Central Powers in 1917, the journal came under government pressure to change its policy. When it refused to do this, the journal lost its mailing privileges. In July, 1917, it was claimed by the authorities that cartoons by Art Young, Boardman Robinson and Henry J. Glintenkamp and articles by Max Eastman and Floyd Dell had violated the Espionage Act. Under this act it was an offence to publish material that undermined the war effort. One of the journals main writers, Randolph Bourne, commented: "I feel very much secluded from the world, very much out of touch with my times. The magazines I write for die violent deaths, and all my thoughts are unprintable."

The Industrial Workers of the World also came under pressure for its opposition to the First World War. In 1914, one of the leaders of the IWW, Joe Haaglund Hill was accused of the murder of a Salt Lake City businessman. Convicted on circumstantial evidence and despite of mass protests, Hill was shot by a firing squad on 19th November, 1915. Whereas another IWW leader, Frank Little, was lynched in Butte, Montana. Another leader of the IWW, William Haywood, was arrested under the Espionage Act.

In an article published in The Liberator, Keller argued: "During the last few months, in Washington State, at Pasco and throughout the Yakima Valley, many IWW members have been arrested without warrants, thrown into bull-pens without access to attorney, denied bail and trial by jury, and some of them shot. Did any of the leading newspapers denounce these acts as unlawful, cruel, undemocratic? No. On the contrary, most of them indirectly praised the perpetrators of these crimes for their patriotic service! On August 1st, of 1917, in Butte, Montana, a cripple, Frank Little, a member of the Executive Board of the IWW, was forced out of bed at three o’clock in the morning by masked citizens, dragged behind an automobile and hanged on a railroad trestle. Were the offenders punished? No. A high government official has publicly condoned this murder, thereby upholding lynch-law and mob rule."

Newspapers that had previously praised Keller's courage and intelligence now drew attentions to her disabilities. The editor of the Brooklyn Eagle wrote that her "mistakes sprung out of the manifest limitations of her development." Keller was furious and wrote a letter of complaint to the newspaper. "At that time the compliments he paid me were so generous that I blush to remember them. But now that I have come out for socialism he reminds me and the public that I am blind and deaf and especially liable to error.... Socially blind and deaf, it defends an intolerable system, a system that is the cause of much of the physical blindness and deafness which we are trying to prevent."

In 1919 Keller appeared in an autobiographical film, Deliverance, in an attempt to spread "a message of courage, a message of a brighter, happier future for all men". Keller as a young girl was played by Etna Ross and as a young woman by Ann Mason. According to one critic: "In the final and most inspirational sequence, we see the real Helen Keller working tirelessly as a public figure to improve conditions for other blind people, and helping them to learn useful trades."

When Helen Keller decided after 1921 that her main work was to be devoted to raising funds for the American Foundation of the Blind, her activities for the socialist movement diminished but did not cease. Philip S. Foner has argued: "No matter what social cause she espoused, Keller was always on the radical side of the movement." As a left-wing socialist she disliked "parlor socialists" who quickly abandoned the struggle when the situation became difficult and later became "hopelessly reactionary."

In 1929 she published her book Mainstream. It included the following: "I had once believed that we are all masters of our fate - that we could mould our lives into any form we pleased ... I had overcome deafness and blindness sufficiently to be happy, and I supposed that anyone could come out victorious if he threw himself valiantly into life's struggle. But as I went more and more about the country I learned that I had spoken with assurance on a subject I knew little about. I forgot that I owed my success partly to the advantages of my birth and environment ... Now, however, I learned that the power to rise in the world is not within the reach of everyone."

Keller's childhood education was depicted in The Miracle Worker, a play by William Gibson, which won the Pulitzer Prize in 1960. An Oscar-winning feature film in 1962, starring Anne Bancroft and Patty Duke, appeared two years later.

Helen Keller died in Westport, Connecticut, on 1st June, 1968.

On this day in 1879 Alexander Soloviev tries to kill Tsar Alexander II. In 1869, two Russian writers, Mikhail Bakunin and Sergi Nechayev published the book Catechism of a Revolutionist. It included the famous passage: "The Revolutionist is a doomed man. He has no private interests, no affairs, sentiments, ties, property nor even a name of his own. His entire being is devoured by one purpose, one thought, one passion - the revolution. Heart and soul, not merely by word but by deed, he has severed every link with the social order and with the entire civilized world; with the laws, good manners, conventions, and morality of that world. He is its merciless enemy and continues to inhabit it with only one purpose - to destroy it."

The book had a great impact on young Russians and in 1876 the group Land and Liberty was formed. Most of the group shared Bakunin's anarchist views and demanded that Russia's land should be handed over to the peasants and the State should be destroyed. It remained a small secret society and at its peak only had around 200 members.

Some reformers favoured a policy of terrorism to obtain reform and on 14th April, 1879, Alexander Soloviev, a former schoolteacher, tried to kill Alexander II. His attempt failed and he was executed the following month. So also were sixteen other men suspected of terrorism. The government responded to the assassination attempt by appointing six military governor-generals that imposed a rigorous system of censorship on Russia. All radical books were banned and known reformers were arrested and imprisoned.

On this day in 1886 Leah Manning, the daughter of a Captain in the Salvation Army, was born in Droitwich, Worcestershire. Educated at St. John's School, Bridgwater, and Homerton College, Cambridge, where she joined the Fabian Society. Manning worked as a teacher in Cambridge and in 1913 she married Will Manning.

A member of the Labour Party, Manning became President of the National Union of Teachers in 1930. The following year she was elected to represent East Islington in the House of Commons.

An opponent of Ramsay MacDonald and his National Government, Manning lost her seat in the 1931 General Election. Four years later Manning unsuccessfully contested Sunderland. Manning was active in the anti-fascist movement and was Secretary of the Co-ordinating Committee Against War and Fascism.

Leah Manning was in the Soviet Union when the Spanish Civil War broke out. She immediately travelled to Spain. She told a friend that her main objective was "to find out what goes on and see if there is anything I can do to help." Her friend, Alvarez del Vayo, the minister of foreign affairs in the new Popular Front government, asked her to go back to London: "It's what we want: someone we know and can trust, who will get back to England and tell the Government what is happening here.... Explain the situation to all your old friends in Parliament. Get them to send out a delegation; tell them we must have transport, medical supplies, arms."

In the 1936 Labour Party Conference, several party members including Leah Manning, Ellen Wilkinson, Stafford Cripps, Aneurin Bevan and Charles Trevelyan, argued that military help should be given to the Spanish Popular Front government, fighting for survival against General Francisco Franco and his right-wing Nationalist Army. Despite a passionate appeal from Senora Isobel de Palencia, the Labour Party supported the Conservative Government's policy of non-intervention.

Leah Manning joined forces with Isabel Brown to establish the Spanish Medical Aid Committee. She later recalled: "We had three doctors on the committee, one representing the TUC and I became its honorary secretary. The initial work of arranging meetings and raising funds was easy. It was quite common to raise £1,000 at a meeting, besides plates full of rings, bracelets, brooches, watches and jewellery of all kinds." Eventually she was replaced by George Jeger as secretary.

Manning made several trips to Spain with supplies. She worked closely with Nan Green, who was a senior administrator and Peter Spencer, the treasurer based in Spain of the British Medical Aid Unit. Other key figures were Kenneth Sinclair Loutit, the head of the medical unit and George Green, who was in charge of the convoys. Green was killed at Ebro. As Manning pointed out in her memoirs: "No one was to blame for this: we were finding our way in unknown territory."

There were times when both Green and Manning worked as nurses. They both cared for Harry Dobson when he was wounded at the Battle of the Ebro. Green later recalled Manning holding his hand until he died. Manning explained in her memoirs: "He had had his spleen removed and Reggie Saxton had given him a blood transfusion. As I stood by he opened his eyes and spoke my name. I recognised him as a comrade whom I had met at a by-election in South Wales, a miner from Tonypandy named Harry Dobson. Dr. Jolly told me that it was not possible that he could live in fact they thought only a few hours, so I determined to stay by him until the end. Actually, it was fifteen hours before he passed away but I did not leave him during that time and he seemed very happy to have me there."

In the spring of 1937 Manning helped to arrange the evacuation of Basque children to Britain and while there witnessed the bombing raid of Guernica. In 1938 Manning returned to Spain where she wrote a report on the hospitals where British doctors and nurses were working.

Manning became the Labour Party candidate for Epping and won the seat in the 1945 General Election. Defeated in 1950 she returned to teaching. Manning unsuccessfully contested Epping in 1951 and 1955. Her autobiography, A Life for Education, was published in 1970.

Leah Manning died on 15th September, 1977.

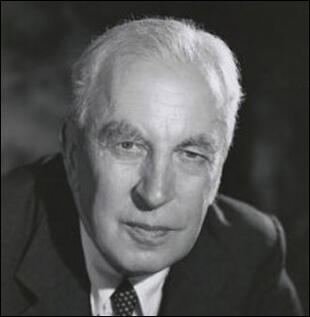

On this day in 1889 Arnold Joseph Toynbee, the nephew of the social reformer, Arnold Toynbee, was born on 14th April 1889. Educated at Winchester and Balliol College, Oxford, he served in the Foreign Office during the First World War and attended the Paris Peace Conference in 1919.

Toynbee became Professor of Modern Greek and Byzantine History at King's College, London (1919-1924) and research professor at the Royal Institute of International Affairs (1925-1955).

Books by Toynbee include Greek Historical Thought (1924), History of the World (12 volumes, 1925-1961), War and Civilization (1951), War and Civilization (1951), Hellenism: The History of a Civilization (1959) and Hannibal's Legacy (1965). Arnold Joseph Toynbee died on 22nd October 1975.

On this day in 1909 Len Crome, the son of a Jewish businessman, was born in Latvia on 14th April, 1909. After being educated locally he went to Scotland and studied medicine in Edinburgh.

Crome found work as a doctor in Blackburn but concerned by the growth of fascism in Europe, volunteered to join a Scottish ambulance unit that was helping the Republican forces fighting in the Spanish Civil War. Crome served in Madrid and after the death of Dr. Mieczyslaw Domanski, he was promoted to the 35th Division's chief medical officer.

Crome worked on the frontline until Juan Negrin decided to withdraw the International Brigades in September 1938 in an attempt to achieve international mediation.

When Crome returned to England he joined the Communist Party. He settled in London and worked as a GP in Camberwell and on the outbreak of the Second World War used the skills developed in Spain to train air-raid wardens.

In December 1942 Crome joined the British Army and served in the Medical Corps in North Africa. During the Allied advance in Italy, Crome commanded the 152 Field Ambulance Unit and won the Military Cross at Monte Cassino. In 1945 he was commandant of the British military hospitals in Naples.

After the war Crome discovered that his mother, father and sister had died in Concentration Camps after the German Army had invaded Latvia.

Crome returned to London and studied neuropathology at the Maudsley Hospital and later worked as a pathologist at the Fountain Hospital in Tooting. He remained active in politics and was secretary of the Society for Cultural Relations with the Soviet Union. He was also chairman of the International Brigade Association.

Crome wrote several books including Pathology of Mental Retardation (1967) and Unbroken: Resistance and Survival in the Concentration Camps (1988).

Len Crome died on 6th May 2001.

On this day in 1914 Hubert Bland died of a heart attack. Bland, youngest of the four children of Henry Bland, a successful commercial clerk, was born in Woolwich, London, on 3rd January, 1855. He was educated at various local schools, and from an early age showed a strong interest in politics. As a youth Bland wanted to join the army but the death of his father forced him to run the family business.

In 1877 Bland met Edith Nesbit a young woman who shared his interest in politics. Bland was a disciple of William Morris and Henry George, and helped to convert Edith to socialism. In 1879 discovered she was pregnant and the baby was born two months after they were married on 22nd April, 1880. According to her biographer, Julia Briggs: "Bland continued to spend half of each week with his widowed mother and her paid companion, Maggie Doran, who also had a son by him, though Edith did not realize this until later that summer when Bland fell ill with smallpox. With characteristic optimism, she forgave him, befriended Maggie, and set about supporting the household by writing sentimental poems and short stories, and by hand-painting greetings cards."

In 1883 Edith and Hubert joined the Fellowship of the New Life, an organisation founded by Thomas Davidson. According to another member, Ramsay MacDonald, the group were influenced by the ideas of Henry David Thoreau and Ralph Waldo Emerson.

Edith and Hubert were both socialists and on 24th October 1883 they decided with their Quaker friend Edward Pease, to form a debating group. They were also joined by Havelock Ellis and Frank Podmore and in January 1884 they decided to call themselves the Fabian Society. Bland chaired the first meeting and was elected treasurer. Nesbit and her husband became joint editors of the society's journal, Today . Soon afterwards other socialists in London began attending meetings. This included Eleanor Marx, Annie Besant, Olive Schreiner, Clementina Black, Sidney Webb and Beatrice Webb.

In April 1884 Edith wrote to her friend, Ada Breakell: "I should like to try and tell you a little about the Fabian Society - it's aim is to improve the social system - or rather to spread its news as to the possible improvements of the social system. There are about thirty members - some of whom are working men. We meet once a fortnight - and then someone reads a paper and we all talk about it. We are now going to issue a pamphlet. I am on the Pamphlet Committee. Now can you fancy me on a committee? I really surprise myself sometimes."

Bland was unpopular with most of the Fabians. George Bernard Shaw described him as "a man of fierce Norman exterior and huge physical strength... never seen without an irreproachable frock coat, tall hat, and a single eyeglass which infuriated everybody. He was pugnacious, powerful, a skilled pugilist, and had a shrill, thin voice reportedly like the scream of an eagle. Nobody dared be uncivil to him."

His biographer, Julia Briggs, argued that he was an unsual socialist: "Bland was an atypical Fabian, since he combined socialism with strongly conservative opinions that reflected his social background and his military sympathies.... He was also strongly opposed to women's suffrage. At the same time he advocated collectivist socialism, wrote Fabian tracts, and lectured extensively on socialism." Bland was unconvinced by democracy and described it as "bumptious, unidealistic, disloyal… anti-national and vulgar".

In 1885 Bland also joined the Social Democratic Federation (SDF). Other members included Tom Mann, John Burns, Eleanor Marx, William Morris, George Lansbury, Edward Aveling, H. H. Champion, John Scurr, Guy Aldred, Dora Montefiore, Frank Harris, Clara Codd, John Spargo and Ben Tillet. However, he did not stay long as he found the views of its leader, H. H. Hyndman, too revolutionary. After his experience of the SDF, Hubert Bland, rejected extremism and advocated what became known as gradualism.

Bland was a freelance journalist until 1889 when he obtained the position as a columnist for the radical newspaper, Manchester Sunday Chronicle . In the newspaper and in several pamphlets that he wrote for the Fabian Society, Bland advocated a mixture of state socialism and imperialism. In The Outlook (1889) Bland argued in favour of the nationalization of the means of production.

In 1893 Hubert Bland joined the Independent Labour Party. However, his support of the Boer War made him unpopular with members of both the ILP and the Fabian Society. Bland argued that the livelihood of British working people depended on the maintenance of the Empire. He wrote that if the British army was defeated in South Africa it would mean "starvation in every city of Great Britain." Unlike most socialists, Bland was an opponent of women's rights. He wrote: "Woman's metier in the world - I mean, of course, civilized woman, the woman in the world as it is - is to inspire romantic passion ... Romantic passion is inspired by women who wear corsets. In other words, by the women who pretend to be what they not quite are."

Edith Nesbit was a regular lecturer and writer on socialism throughout the 1880s. However she gave less time to these activities after she published The Story of the Treasure-Seekers (1899). Julia Briggs has pointed out: "With the creation of Oswald Bastable, she knew that she had discovered a highly original way of writing about and for children, and from this point in her career she never looked back. She now invented the children's adventure story, more or less single-handed, adding to it fantasy, magic, time-travel, and a delightful vein of subversive comedy. The next ten years or so saw the publication of all her major work, and in the mean time she was also composing poems, plays, romantic novels, ghost stories, and tales of country life."

Claire Tomalin has argued: "Bland is one of the minor enigmas of literary history in that everything reported of him makes him sound repellent, yet he was admired, even adored, by many intelligent men and women... He did not aspire to be consistent. He allowed his wife to support him with her pen for some years, but was always opposed to feminism... In mid-life he joined the Catholic Church, a further cosmetic touch to his old-world image, but without modifying his behaviour or even bothering to attend more than the statutory minimum of masses."

In 1911 Bland began to go blind. Unable to work, Bland was supported by his wife, Edith Nesbit, who was now a very successful novelist.

On this day in 1925 painter John Singer Sargent died in his sleep at home in Tite Street having suffered a heart attack. He was buried in Brookwood Cemetery, Woking, on 18th April.

The eldest surviving child of American parents, Dr Fitzwilliam Sargent (1820–1889) and his wife, Mary Newbold Singer (1826–1906), was born in Florence on 12th January, 1856. His mother came from a very wealthy family in Philadelphia.

He studied painting in Italy and France and in 1884 caused a sensation at the Paris Salon with his painting of of a young socialite named Virginie Amélie Avegno Gautreau. Exhibited as Madame X, people complained that the painting was provocatively erotic.

His biographers, Elaine Kilmurray and Richard Ormond, have argued: "Its largely hostile reception was one factor spurring his decision to leave Paris for London. Sargent had already been asked to paint members of the Vickers family (connected with the famous armaments firm) in England" Over the next few years he established himself as the country's leading portrait painter. This included portraits of Joseph Chamberlain (1896), Frank Swettenham (1904) and Henry James (1913). Sargent made several visits to the USA where as well as portraits he worked on a series of decorative paintings for public buildings such as the Boston Public Library (1890).

In London he became friends with Henry Tonks and William Rothenstein. He possessed a huge appetite and became corpulent in middle age. Rothenstein pointed out in Men and Memories (1932) that he used to visit "the Hans Crescent Hotel, where, from the table d'hôte luncheon of several courses, he could assuage his Gargantuan appetite".

Sargent became the most important portrait painter of the period and demand very high prices for his work. He received £2,100 for The Ladies Alexandra, Mary, and Theo Acheson (1902), £3,000 for his group of medical doctors Professors Welch, Halsted, Osler and Kelly (1906)and £2,500 for his painting of the Marlborough family.

Sargent spent most of the First World War in the United States. In 1918 Sargent was commissioned to paint a large painting to symbolize the co-operation between British and American forces during the war. Sargent was sent to France with Henry Tonks. One day Sargent visited a casualty clearing station at Le Bac-de-Sud. While at the casualty station he witnessed an orderly leading a group of soldiers that had been blinded by mustard gas. He used this as a subject for a naturalist allegorical frieze depicting a line of young men with their eyes bandaged. Gassed soon became one of the most memorably haunting images of the war. While in France Sargent also painted The Interior of a Hospital Tent (1918) and A Street in Arras (1918).

It has been claimed by Elaine Kilmurray and Richard Ormond: "The impression that emerges from descriptions by his sitters is of a vigorous, decisive, and driven artist. There are stories of Sargent's rushing to and from the easel, totally absorbed, placing his brushstrokes in gestures of absolute precision, of the cries of frustration as he rubbed out, scraped down, reworked, and grappled with the problems of representation, cries punctuated by his mild expletives... Occasionally, he would dash to the piano and play as a brief respite from painting. He was single-minded about what he wanted to achieve and would brook no interference - an approach born of professional self-belief rather than personal arrogance, from which he was remarkably free. He insisted on the right to select his sitters' costumes and accessories, and took brisk exception to comments from his sitters and their families about the truth of the likenesses and characterizations he created."

Cynthia Asquith claims that he was a "curiously inarticulate man, he used to splutter and gasp, almost growl with the strain of trying to express himself; and sometimes, like Macbeth at the dagger, he would literally clutch at the air in frustrated efforts to find, with many intermediary ‘ers’ and ‘ums’, the most ordinary words." Vernon Lee, a very close friend, added: "He was very shy, having I suppose a vague sense that there were poets about… I think John is singularly unprejudiced, almost too amiably candid in his judgements… He talked art & literature, just as formerly, and then, quite unbidden, sat down to the piano and played all sorts of bits of things."

Evan Charteris, the author of John Sargent (1927), has written: "He read no newspapers; he had the sketchiest knowledge of current movements outside art; his receptive credulity made him accept fabulous items of information without question. He would have been puzzled to answer if he were asked how nine-tenths of the population lived, he would have been dumbfounded if asked how they were governed."

John Singer Sargent died in his sleep on 14th April 1925 at home in Tite Street having suffered a heart attack. He was buried in Brookwood Cemetery, Woking, on 18th April.

On this day in 1931 King Alfonso XIII abdicates. Alfonso, the posthumous son of Alfonso XII and Maria Christina of Austria, was born in Madrid, Spain, on 17th May 1886. His mother acted as regent until 1902 when he assumed full power.

In 1906 Alfonso XIII married Princess Ena of Battenberg, granddaughter of Queen Victoria. An attempt was made to kill the couple on their wedding day. This was the first of several attempts to kill Alfonso.

Alfonso XIII became increasingly autocratic and in 1909 was condemned for ordering the execution of the radical leader, Ferrer Guardia, in Barcelona. He also prevented liberal reforms being introduced before the First World War.

Blamed for the Spanish defeat in the Moroccan War (1921) Alfonso XIII was in constant conflict with Spanish politicians. His anti-democratic views encouraged Miguel Primo de Rivera to lead a military coup in 1923. Alfonso gave his support to Rivera's military dictatorship but Rivera lost power in 1930 and the following year he agreed to democratic elections.

When the Spanish people voted overwhelmingly for a republic, Alfonso was advised that the only way to avoid large-scale violence was to go into exile. Alfonso agreed and left the country on 14th April, 1931.

When the Spanish Civil War broke out Alfonso made it clear he favoured the military uprising against the Popular Front government. However, in September 1936 General Francisco Franco announced that the Nationalists would never accept Alfonso as king.

Alfonso XIII died in Rome, Italy, on 28th February, 1941.

On this day in 1935 the worst dust storm took place in Oklahoma. The First World War severely disrupted agriculture in Europe. This worked to the advantage of farmers in America who were able to use new machines such as the combine harvester to dramatically increase production. During the war American farmers were able to export the food that was surplus to requirements of the home market.

By the 1920s, European agriculture had recovered and American farmers found it more difficult to find export markets for their goods. Farmers continued to produce more food than could be consumed and consequently prices began to fall. The decline in agricultural profits meant that many farmers had difficulty paying the heavy mortgages on their farms. By the 1930s many American farmers were in serious financial difficulties.

When Franklin D. Roosevelt was elected as president, he asked Congress to pass the Agricultural Adjustment Act (1933). The AAA paid farmers not to grow crops and not to produce dairy produce such as milk and butter. It also paid them not to raise pigs and lambs. The money to pay the farmers for cutting back production of about 30% was raised by a tax on companies that bought the farm products and processed them into food and clothing.