On this day on 5th May

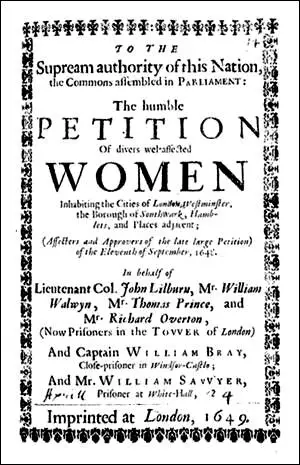

On this day in 1649 Elizabeth Lilburne publishes A Petition of Women. Elizabeth, like her husband, John Lilburne, was a committed member of the Levellers. The supporters of the Leveller movement called for the release of John Lilburne. This included Britain's first ever all-women petition, that was supported by over 10,000 signatures. This group, led by Elizabeth Lilburne and Katherine Chidley, presented the petition to the House of Commons on 25th April, 1649.

MPs reacted intolerantly, telling the women that "it was not for women to petition; they might stay home and wash their dishes... you are desired to go home, and look after your own business, and meddle with your housewifery". One woman replied: "Sir, we have scarce any dishes left us to wash, and those we have not sure to keep." When another MP said it was strange for women to petition Parliament one replied: "It was strange that you cut off the King's head, yet I suppose you will justify it."

The following month Elizabeth Lilburne produced A Petition of Women: "That since we are assured of our creation in the image of God, and of an interest in Christ equal unto men, as also of a proportional share in the freedoms of this commonwealth, we cannot but wonder and grieve that we should appear so despicable in your eyes as to be thought unworthy to petition or represent our grievances to this honourable House. Have we not an equal interest with the men of this nation in those liberties and securities contained in the Petition of Right, and other the good laws of the land? Are any of our lives, limbs, liberties, or goods to be taken from us more than from men, but by due process of law and conviction of twelve sworn men of the neighbourhood? Would you have us keep at home in our houses, when men of such faithfulness and integrity as the four prisoners, our friends in the Tower, are fetched out of their beds and forced from their houses by soldiers, to the affrighting and undoing of themselves, their wives, children, and families?"

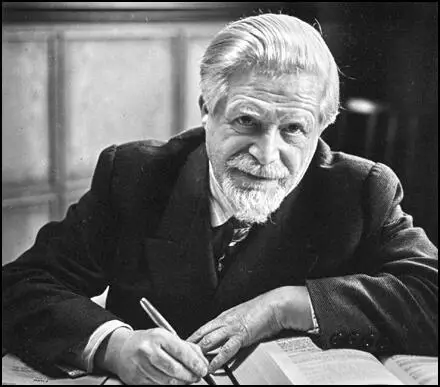

On this day in 1672 artist Samuel Cooper died. Cooper, the eldest child of Richard Cooper and Barbara Hoskins, was probably born in London in about 1608. After studying painting under his uncle, John Hoskins, he travelled around Europe. According to Samuel Pepys, during this period he learnt to to speak French.

In 1642 Cooper married Christiana Turner (1623–1693). In 1650 Cooper moved with his wife to one of the most substantial houses in Henrietta Street, in Covent Garden. There were no children of the marriage.

During the English Civil War Cooper established himself as a portrait painter, who only worked in miniatures.He painted several "portraits of men in armour usually against a dark background". This included paintings of John Milton, George Monck, John Pym, Henry Ireton, Robert Lilburne and John Carew.

Cooper's first portrait of Oliver Cromwell was painted in 1649. Cromwell selected artists like Cooper who would present him "plain both in character and in clothing". It has been pointed out that plainness had a political purpose, presenting Cromwell as a "sober, honest alternative to the tradition of royal vanity, excess and arrogance he’d just replaced". Alfred L. Rouse argues that "Cooper rendered the finest portrait of the great man, painted with penetrating sense of character."

Cromwell once told the artist, Peter Lely to "use all your skill to paint my picture truly like me and not flatter me at all. Remark all these roughness, pimples, warts and everything as you see me. Otherwise I’ll never pay a farthing for it." Cooper obviously followed the same instructions and it seems that he was responsible for more paintings of Cromwell than any other artist.

Cooper was commissioned to paint members of Cromwell's family, including his son, Richard Cromwell. However, this did not stop him being employed by Charles II upon his acquisition to the throne in 1660. Cooper was also called upon to paint miniature portraits of his mistresses and children.

In January 1662, Samuel Cooper was chosen to provide the art work of the King for a profile for the new coinage. John Evelyn was present when it was carried out. "I was called to his Majesty's closet when Mr. Cooper, the rare limner, was crayoning of the King's face and head, to make the stamps by, for the new milled money now contriving, I had the honour to hold the candle whilst it was doing, he choosing the night and candle-light for the better finding out the shadows. During this his Majesty discoursed with me on several things relating to painting and graving."

Cooper's biographer, John Murdoch, argues that his portrait of James, the Duke of York, in 1661 "is an excellent example of the development in his orthodox miniature portraiture at this period. It is bright and direct in its lighting, and subtly enriched in its representation of the sitter's complexion." In 1663 Cooper was appointed as king's limner.

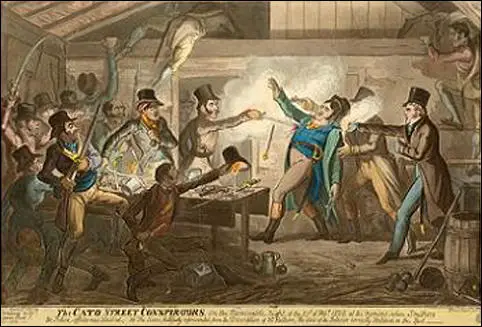

On this day in 1820 agent provocateur George Edwards wrote a letter to Henry Hobhouse, Permanent Under-Secretary at the Home Office: "According to your desire I gave all the papers I had in my possession together with the copy of Depositions to the gentleman you sent to me on Sunday evening last. I am now in the Isle of Guernsey and think I may remain here in perfect safety till you direct otherwise. My money will be exhausted by the time I hear from you. I beg leave your benevolent attention to my family whom I am sure must want financial assistance by the time this letter reaches you. Whatever way you direct my wife to proceed in, she will get my brother to accomplish. All letters I receive from you shall be destroyed as soon as read."

George Edwards was born in Clerkenwell in 1788. His mother was an alcoholic and for a while he lived with his father in Bristol. After returning to London he was apprenticed to a statue maker in Smithfield. According to people who knew him from this period, Edwards was very poor and often went about barefoot. In the 1790s Edwards was making plaster of Paris busts of famous people and selling them on street-corners. Edwards moved to Windsor where he rented a small shop in Eton High Street. One of his customers was Major-General Sir Herbert Taylor, who recruited him as a Home Office spy.

In 1818 Edwards moved back to London where he made friends with John Brunt, a member of the Spencean Philanthropists. Edwards appeared to hold radical political views and talked about wanting to kill members of the government. Brunt introduced Edwards to his radical friends and he was soon attending Spencean meetings. Edwards sent a constant flow of reports to the authorities. His accounts of the meetings, which are preserved in the Public Record Office, were written on narrow strips of paper that were then folded into a small square and passed to John Stafford, Chief Clerk at Bow Street Police Station.

Arthur Thistlewood and Edwards got on well together. Some of the group raised doubts about Edwards and suggested he might be a spy. On one occasion Edwards attempted to give one member, William Tunbridge, a pistol that he could use against the government. Tunbridge refused replying: "Mr. Edwards, you may tell your employers that they will not catch me in their trap." Thistlewood was convinced Edwards was genuine and in December 1819, he made him his aide-de-camp.

In 1820 Edwards played an active role in persuading people he met to join the Spencean Philanthropists. He also joined the Marylebone Union Reading Society where he recruited several new members to Thistlewood's group. At meetings Edwards constantly called for an armed uprising to overthrow the government. It was Edwards' idea to start the revolution by assassinating Lord Castlereagh and Lord Sidmouth. It was also Edwards who told Thistlewood about the item in the New Times that revealed that several members of the British government were going to have dinner at Lord Harrowby's house at 39 Grosvenor Square.

George Edwards kept John Stafford fully informed on the Cato Street Conspiracy and the authorities had no difficulty in arresting all the men involved in the plot. After the experience of the previous trial of the Spenceans, the Home Secretary, Lord Sidmouth was unwilling to use the evidence of his spies in court. Edwards, the person with a great deal of information on the conspiracy, was never called. In fact, by the time the trial took place, Edwards had already left the country.

After the execution of Arthur Thistlewood, William Davidson, James Ings, Richard Tidd, and John Brunt questions were raised in Parliament about the role played by Edwards in this case. On 2nd May, 1820, Matthew Wood stated in the House of Commons that he had information that revealed that Edwards was an agent provocateur who had organised the Cato Street Conspiracy himself and then betrayed it for 'Blood Money'. Joseph Hume complained that Edwards was one of several spies that the government had used to incite rebellion in an effort to smear the campaign for parliamentary reform.

During the trial of Arthur Thistlewood and the other conspirators, Edwards was living in Guernsey. This was only a temporary hiding place and after a short period in Guernsey the government arranged for him to obtain a new identity, and like several former government spies, George Edwards, now known as George Parker, was sent to South Africa. Edwards worked as a modeller at Green Point until his death on 30th November, 1843.

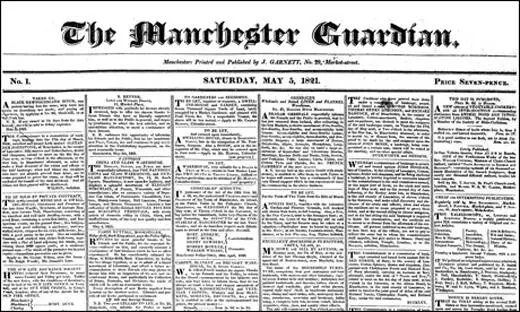

On this day in 1821 the first edition of the Manchester Guardian was published. In 1819 a group of men involved in the textile industry in Manchester held regular meetings in the home of John Potter. The men all shared the same passion for political reform. The group included Potter and his two sons, Thomas and Richard, John Shuttleworth, John Edward Taylor, Archibald Prentice, Joseph Brotherton, Absalom Watkin and William Cowdray. The group strongly objected to a parliamentary system that denied such important industrial cities such as Manchester, Leeds and Birmingham, representation in the House of Commons. A member of this group, William Cowdray, owned the Manchester Gazette, and this provided a forum to express their views. John Edward Taylor and Archibald Prentice in particular were regular contributors to the newspaper.

Most of the men in the Potter group held Nonconformist religious views. This was not unusual in Manchester as Nonconformists outnumbered Anglicans by two to one. Potter's group was particularly concerned about the close link between the government and the Anglican Church, and feared that in future schools would be used to indoctrinate children. Members of the group were all supporters of Joseph Lancaster and his Nonconformist schools movement.

On occasions, this group of middle-class liberals, worked with working-class radicals in Manchester in their campaign for parliamentary reform and the repeal of the Corn Laws. Although they believed in the principles and objectives of people like John Knight, Joseph Johnson, James Wroe, Samuel Bamford, John Saxton, George Swift and Joseph Healey, they did not approve of the methods that working-class radicals were using to obtain the vote.

In 1818, John Knight, James Wroe and John Saxton started the radical newspaper, the Manchester Observer. Within twelve months the Manchester Observer was selling 4,000 copies a week. Although it started as a local paper, by 1819 it was sold in most of the large towns and cities in Britain. Henry Hunt called the Manchester Observer "the only newspaper in England that I know, fairly and honestly devoted to such reform as would give the people their whole rights."

In March 1819, working-class radicals in Britain formed the Patriotic Union Society. Joseph Johnson was appointed secretary of the organisation and James Wroe became treasurer. The main objective of the Society was to obtain parliamentary reform and during the summer of 1819 it decided to invite Major John Cartwright and Henry Orator Hunt to speak at a public meeting in Manchester. The men were told that this was to be "a meeting of the county of Lancashire, than of Manchester alone. I think by good management the largest assembly may be procured that was ever seen in this country." Cartwright was unable to attend but Hunt agreed and the meeting was arranged to take place at St. Peter's Field on 16th August.

Middle-class liberals, such as John Edward Taylor and Archibald Prentice, had doubts about the wisdom of holding this meeting, but like other supporters of parliamentary reform, they attended in an effort to show the government how strongly the people of Manchester felt about this issue. Both John Edward Taylor and Archibald Prentice went home early and missed the soldiers attacking the crowd.

When Taylor and Prentice heard the news they quickly returned to St. Peter's Field and began interviewing eyewitnesses. They discovered that John Tyas of The Times, the only reporter from a national newspaper at the meeting, had been arrested and imprisoned. Taylor and Prentice feared that this was an attempt by the government to suppress news of the event. The next edition of the Manchester Gazette was not due out to Saturday. Taylor and Prentice decided to send their reports to London newspapers.

Thomas Barnes, editor of The Times, had a policy of not naming the writers of the articles that appeared in his newspaper, however, it is believed that the piece that appeared on Wednesday 18th August, was written by John Edward Taylor. It was definitely very similar to the account that appeared in the Saturday edition of the Manchester Gazette. Taylor described what had taken place as the St. Peter's Field Tragedy. However, the Manchester Observer called it the Peterloo Massacre and this eventually became the accepted term for the attack on the crowd.

The government responded to the events at St. Peter's Field by passing the Six Acts. Middle-class liberals like Taylor, Prentice and Shuttleworth was radicalized by these events. Disillusioned with the Manchester Gazette, the group decided to start their own newspaper. Eventually eleven men, all of them involved in the textile industry, raised £1,050 for the venture.

John Edward Taylor was chosen as editor and Jeremiah Garnett was recruited as a printer and reporter. Garnett had worked for the Tory newspaper, Manchester Chronicle and had been their reporter at the Peterloo Massacre. Although Garnett had his reporter's notebook confiscated by a special constable, he was still able to write a full description of what happened. Charles Wheeler, disapproved of Garnett's account and refused to print his article. Garnett resigned in protest and had been working in Huddersfield until Taylor brought him back to Manchester. Although no other journalists were to be employed on the newspaper, Archibald Prentice and John Shuttleworth agreed to supply weekly articles.

Taylor and his partners purchased a Stanhope Press that printed 200 sheets an hour. Taylor was aware that national newspapers were using a Koenig Steam Press that printed 1,000 sheets an hour. However, it would be seven years before the group could afford to buy one of these machines.

It was decided to call the newspaper the Manchester Guardian. A prospectus was published which explained the aims and objectives of the proposed newspaper. It included the passage: "It will zealously enforce the principles of civil and religious Liberty, it will warmly advocate the cause of Reform; it will endeavour to assist in the diffusion of just principles of Political Economy."

The first four-page edition appeared on Saturday 5th May, 1821 and cost 7d. Of this sum, 4d was a tax imposed by the government. The Manchester Guardian, like other newspapers at the time, also had to pay a duty of 3d a lb on paper and three shillings and sixpence on every advertisement that was included. These taxes severely restricted the number of people who could afford to buy newspapers. The Manchester Guardian, like all newspapers based outside of London, could only afford to publish once a week.

In the first couple of years the weekly circulation of the Manchester Guardian hovered around a 1,000 copies. Readership was much higher than this with a large number being purchased by newsrooms (a place where people could go and read a selection of newspapers). The account books of John Edward Taylor show that newsrooms as far away as Glasgow, Hull and Exeter purchased the newspaper. When the Manchester Guardian was first published in 1821, Manchester had six other weekly newspapers. Four were published on Saturday and two on Tuesday. The Manchester Mercury, Chronicle, Exchange Herald and the British Volunteer supported the Tories, whereas the Manchester Gazette was in favour of moderate reform. The final paper, the Manchester Observer, promoted radicalism and with a circulation of 4,000, was easily the best-selling newspaper in Manchester. However, the Manchester Observer had very few advertisers and was constantly being sued for libel. Several of their journalists, including John Wroe and John Saxton had been sent to prison for articles they had written criticizing the government.

With the arrival of the Manchester Guardian, the Manchester Observer decided to cease publication. In its last edition the editor wrote: "I would respectfully suggest that the Manchester Guardian, combining principles of complete independence, and zealous attachment to the cause of reform, with active and spirited management, is a journal in every way worthy of your confidence and support."

Sales of the Manchester Guardian continued to grow. By 1823 it reached 2,000 and two years later it was over 3,000. Taylor was helped by Manchester's fast growing population. This not only provided more potential readers, but emphasized Taylor's point that Manchester needed to be represented in Parliament.

Although John Edward Taylor was successful in using the Manchester Guardian to gain more supporters for his political views, he had upset some old friends in the process. Archibald Prentice, Thomas Potter and John Shuttleworth all accused him of moving to the right. They complained when the Manchester Guardian refused to support the campaign by John Hobhouse and Michael Sadler to reduce child labour in the textile industry. Taylor's view was that "though child labour is evil, it is better than starvation". He also refused to support Richard Oastler and the Ten Hour Movement. Taylor argued that this proposed legislation would cause "the gradual destruction of the cotton industry".

Taylor's views on parliamentary reform also became more conservative. John Edward Taylor no longer believed in universal suffrage and now argued that "the qualification to vote ought to be low enough to put it fairly within the power of members of the labouring classes by careful, steady and preserving industry to possess themselves of it, yet not so low as to give anything like a preponderating influence to the mere populace. The right of representation is not an inherent or abstract right, but the mere creation of an advanced condition of society."

Taylor's old friend, Archibald Prentice, became his strongest critic and accused him of betraying the reformers. In 1824 William Cowdray's widow told Prentice she was willing to sell the Manchester Gazette for £1,600. With the financial help of John Shuttleworth, Thomas Potter and Richard Potter, Archibald Prentice purchased the Manchester Gazette and moved it to the left of the Manchester Guardian.

Without articles written by people like John Shuttleworth and Archibald Prentice, the Manchester Guardian moved further to the right. In 1826 the Manchester Guardian gave its support to Tory politicians such as George Canning and William Huskisson. Although John Edward Taylor regretted the Tories opposition to parliamentary reform and Catholic Emancipation, he thought that it was better to support liberal Tories with power than to campaign for Whig reformers.

In 1831 radicals were appalled when a Manchester Guardian reporter, John Harland, gave evidence about what speakers had said at a parliamentary reform meeting. As a result of John Harland's testimony, several radicals were sent to prison for sedition. Instead of punishing Harland, Taylor made him a partner in the business. The newspaper's move to the right did not damage circulation. By the 1830s John Edward Taylor was selling over 3,000 copies a week. What is more, the Manchester Guardian was Britain's third most successful provincial newspaper.

The government's decision in 1836 to reduce the tax on newspapers also helped sales. Taylor was able to cut the price to 4d while increasing the size of the newspaper. The paper also became a bi-weekly. In 1837 the Wednesday edition sold over 4,100 whereas on Saturday it was close to 6,000 copies.

After the death of John Edward Taylor in January 1844, Jeremiah Garnett became the new editor of the Manchester Guardian. Circulation continued to rise and by 1850 reached 9,110. Garnett was a supporter of the Liberal Party. He constantly defended the cause of individual liberty and campaigned for an increase in religious freedom. This included advocating equal rights for unpopular minorities such as Roman Catholics. Garnett's Manchester Guardian also gave its support to the 1857 Divorce Bill.

After the tax on newspapers was finally removed in 1855, the Manchester Guardian changed from being a bi-weekly to a daily newspaper. Two years later Garnett reduced the price to a penny.

Jeremiah Garnett retired in 1861 and was replaced by John Taylor, the son of John Edward Taylor, the first editor of the Manchester Guardian. Taylor revived the early radicalism of the founders of the newspaper. As well as supporting the Parliamentary Reform Act (1867) and the Secret Ballot Act (1872) the Manchester Guardian also began to carry out in-depth investigations into social problems.

Taylor ran the London office and the actual editing was done by a group of writers in Manchester: Robert Dowman, H. M. Acton and J. M. Maclean. Taylor decided that he needed to appoint an editor who worked with the writers. His choice was his cousin, Charles Prestwich Scott. It was agreed that Scott should receive a salary of £400 a year and one-tenth of the profits.

Charles Prestwich Scott was an advocate of parliamentary reform. As editor he gave strong support to Jacob Bright's Bill for Women's Suffrage. Scott also joined Elizabeth Butler in her campaign against the Contagious Diseases Act.

Taylor did not share Scott's views on female suffrage and ordered him not to use the Manchester Guardian to increase the franchise. On 29th April, 1892, Taylor wrote to Scott again on this issue: "Your article yesterday for the Female Suffrage Bill was adroitly done, and your display of the cloven foot most discreetly managed; still it was quite visible. I must ask you not to advocate this measure whilst I live." Although Scott was now receiving 25% of the profits of the Manchester Guardian, Taylor still controlled 75% of the company and had the power to over-rule his editor. Scott no longer received a salary but he did well from this agreement as the profits during this period ranged from £12,000 to £24,000 a year.

In the 1895 General Election, Scott stood as the Liberal Party candidate for North-East Manchester. He won with a majority of 667 and once in the House of Commons identified himself with the left-wing of the party. In Parliament Scott advocated women's suffrage and reform of the House of Lords.

In 1899 Scott strongly opposed the Boer War. This created a great deal of public hostility and both Scott's house and the Manchester Guardian building had to be given police protection. Sales of the newspaper also dropped during this period. However, despite holding unpopular views on the war, Scott managed to regain his seat in the 1900 General Election. With the help of his able lieutenants, C. E. Montague and L. T. Hobhouse, Scott continued to edit the newspaper during his period in Parliament.

When John Taylor died in October 1905, he left instructions in his will that C. P. Scott could buy the Manchester Guardian for £10,000. The trustees were unwilling to obey these demands and eventually Scott had to raise £242,000 to buy the newspaper. This was a high price considering the newspaper only made a profit of £1,200 in 1905.

Scott initially opposed Britain's involvement in the First World War. Scott supported his friends, John Burns, John Morley and Charles Trevelyan, when they resigned from the government over this issue. However, he refused to join anti-war organizations such as the Union of Democratic Control (UDC). As he wrote at the time: "I am strongly of the opinion that the war ought not to have taken place and that we ought not to have become parties to it, but once in it the whole future of our nation is at stake and we have no choice but do the utmost we can to secure success."

During the summer of 1914 most of the newspapaper's writers, including C. E. Montague, Leonard Hobhouse, Herbert Sidebottom, Henry Nevinson, and J. A. Hobson called for Britain to remain neutral in the growing conflict in Europe. However, once war was declared, most gave their support to the government. J. A. Hobson remained opposed to Britain's involvement and joined the and anti-war organisation, the Union of Democratic Control (UDC). Hobson served on the UDC's executive council and wrote the book Towards International Government (1914) which advocated the formation of a world body to prevent wars.

C. E. Montague, although forty-seven with a wife and seven children, volunteered to join the British Army. Grey since his early twenties, Montague died his hair in an attempt to persuade the army to take him. On 23rd December, 1914, the Royal Fusiliers accepted him and he joined the Sportsman's Battalion. Montague was later promoted to the rank of second lieutenant and transferred to Military Intelligence. For the next two years he had the task of writing propaganda for the British Army and censoring articles written by the five authorized English journalists on the Western Front (Perry Robinson, Philip Gibbs, Percival Phillips, Herbert Russell and Bleach Thomas). Howard Spring, another of the newspaper's writers, also worked for the Military Intelligence in France.

Henry Nevinson, the newspaper's main war reporter, was highly critical of the tactics used by the British Army but was unable to get this view past the censors. C. P. Scott and Leonard Hobhouse opposed conscription introduced in 1916 and the following year supported attempts made by Arthur Henderson to secure a negotiated peace.

Although Scott was critical of the way David Lloyd George handled the peace negotiations at Versailles, he supported him in his struggle with Herbert Asquith. After the Conservative victory in the 1922 General Election, Scott worked hard to unite the Liberal Party. However, his loyal support of Lloyd George made this an impossible task.

Kingsley Martin went to work for the Manchester Guardian in 1927: "C. P. Scott was a remarkable figure. At the age of eighty he was bent nearly double, blind in one eye, but more fierce in expression than any other man I have known. He still rode his bicycle through the muddy and dangerous streets of Manchester, swaying between the tramlines, with white hair and whiskers floating in the breeze, equally oblivious of rain and traffic. Unconsciously, I am sure, he thought that no one in Manchester would hurt him."

C. E. Montague, who was married to C. P. Scott's only daughter, Madeline, died in June, 1929. He had worked for the Manchester Guardian for over thirty-five years. The following month, Scott, after fifty-seven years as editor, decided to retire. Scott had initially expected his eldest son, Laurence Scott, to succeed him as editor. However, while involved in charity work in the Ancoats slums, he caught tuberculosis and died. It was therefore, Edward Scott, the youngest son, who took over from his father. Although officially retired, C. P. Scott kept a close watch over the newspaper until his death on 1st January, 1932.

It its editorial that week, The New Statesman compared Scott to Lord Northcliffe: "Every newspaper lives by appealing to a particular public. It can only go ahead of its times if it carries its public with it. Success in journalism depends on understanding the public. But success is of two kinds. Northcliffe had a genius for understanding his public and he used it for making money, not for winning permanent influence.... C. P. Scott succeeded in a different way. He had just as much flair, just as acute an understanding of his public as Northcliffe. But his relationship to it was a professional, not a commercial relation. He taught his public to trust his integrity, to rely on the facts he told them, to respect his judgment, and to listen to his criticism. He offered his undivided services. I remember his saying that there was a definite moment in his life, the equivalent of a religious conversion, when he dedicated his life wholly to his paper and the causes it served."

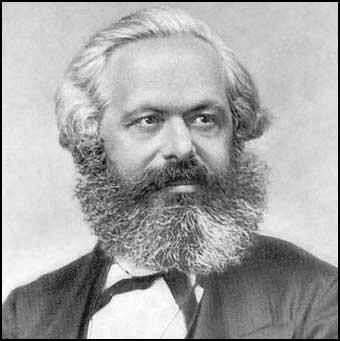

On this day in 1818 Karl Marx, the third of nine children and only surviving son of Hirschel and Henrietta Marx, was born in Trier, Germany. His father was a lawyer and to escape anti-Semitism decided to abandon his Jewish faith when Karl was a child. Although the majority of people living in Trier were Catholics, Marx decided to become a Protestant. He also changed his name from Hirschel to Heinrich.

Marx attended Friedrich-Wilhelm Gymnasium in Trier. At the age of seventeen he wrote about his ambitions for the future and the morality of the type of work he intended to do: ‘If he is working only for himself, he can become a famous scholar, a sage, a distinguished writer, but never a complete, a truly great, man."

Marx entered Bonn University to study law in 1835. His father warned him to look after his body as well as his mind: "In providing really vigorous and healthy nourishment for your mind, do not forget that in this miserable world it is always accompanied by the body, which determines the well-being of the whole machine. A sickly scholar is the most unfortunate being on earth. Therefore, do not study more than your health can bear."

At university he spent much of his time socialising and running up large debts. His father was horrified when he discovered that Karl had been wounded in a duel. His father asked him: "Is duelling then so closely interwoven with philosophy? Do not let this inclination, and if not inclination, this craze, take root. You could in the end deprive yourself and your parents of the finest hopes that life offers."

Heinrich Marx agreed to pay off his son's debts but insisted that he moved to the more sedate Berlin University. At this time he also began a relationship with Jenny von Westphalen. She was the daughter of Baron Ludwig von Westphalen, and as Francis Wheen pointed out: "It may seem surprising that a twenty-two-year-old princess of the Prussian ruling class... should have fallen for a bourgeois Jewish scallywag four years her junior, rather than some dashing grandee with a braided uniform and a private income; but Jenny was an intelligent, free-thinking girl who found Marx's intellectual swagger irresistible. After ditching her official fiance, a respectable young second lieutenant, she became engaged to Karl in the summer of 1836."

The move to Berlin resulted in a change in Marx and for the next few years he worked hard at his studies, especially when he switched from law to philosophy. Marx came under the influence of one of his lecturers, Bruno Bauer, whose atheism and radical political opinions got him into trouble with the authorities. Bauer introduced Marx to the writings of G. W. F. Hegel, who had been the professor of philosophy at the university until his death in 1831.

Karl Marx wrote a long letter to his father describing his conversion to Hegel's theories: "There are moments in one's life, which are like frontier posts marking the completion of a period but at the same time clearly indicating a new direction. At such a moment of transition we feel compelled to view the past and the present with the eagle eye of thought in order to become conscious of our real position. Indeed, world history itself likes to look back in this way and take stock."

His father was upset by his decision to abandon his law degree. Marx rarely replied to his parents' letters. He did not return home during university holidays and showed no interest in his family. His father appeared to accept defeat when he wrote: "I can only propose, advise. You have outgrown me; in this matter you are in general superior to me, so I must leave it to you to decide as you will."

Karl Marx was especially impressed by Hegel's theory that a thing or thought could not be separated from its opposite. For example, the slave could not exist without the master, and vice versa. Hegel argued that unity would eventually be achieved by the equalising of all opposites, by means of the dialectic (logical progression) of thesis, antithesis and synthesis. This was Hegel's theory of the evolving process of history.

Heinrich Marx, aged fifty-seven, died of tuberculosis on 10th May 1838. Marx now had to earn his own living and he decided to become a university lecturer. After completing his doctoral thesis at the University of Jena, Marx hoped that his mentor, Bruno Bauer, would help find him a teaching post. However, Bauer was dismissed as a result of his outspoken atheism and was unable to help.

Marx gradually began to question the purpose of philosophy: "Since every true philosophy is the intellectual quintessence of his time, the time must come when philosophy not only internally by its content, but also externally through its form, comes into contact and interaction with the real world of its day." Three years later he commented: "The philosophers have only interpreted the world, in various ways. The point, however, is to change it."

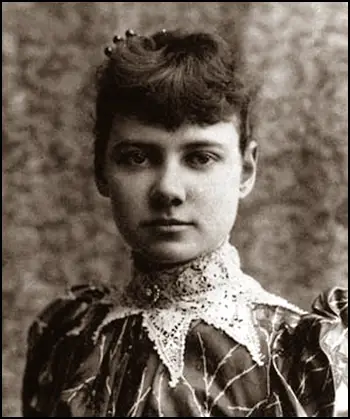

On this day in 1864 Elizabeth Cochrane was born in Cochran Mills, Allegheny County, Pennsylvania. Her father died six years later, leaving her mother, Mary Jane Cochrane, with fifteen children to raise. Elizabeth was not an impressive student at school but she did develop a strong desire to be a writer.

The family were fairly poor and when Elizabeth reached sixteen she moved to Pittsburgh to find work. She soon discovered that only low-paid occupations were available to women. In 1885 she read an article in the Pittsburgh Dispatch entitled What Girls Are Good For. The male writer argued that women were only good for housework and taking care of children. Elizabeth was furious and wrote a letter of protest to the editor. George Madden responded by asking her what articles she would write if she was a journalist. She replied that newspapers should be publishing articles that told the stories of ordinary people. As a result of her letter, Madden commissioned Elizabeth, who was only eighteen, to write an article on the lives of women.

Elizabeth accepted, but as it was considered improper for at the time for women journalists to use their real names, she used a pseudonym: Nellie Bly. She decided to write an article on divorce based on interviews with women that she knew. In the piece, Bly used the material to argue for the reform of the marriage and divorce laws. Madden was so impressed with the article he hired her as a full-time reporter for the Pittsburgh Dispatch. Bly's journalistic style was marked by her first-hand tales of the lives of ordinary people. She often obtained this material by becoming involved in a series of undercover adventures. For example, she worked in a Pittsburgh factory to investigate child labour, low wages and unsafe working conditions. Bly was not only interested in writing about social problems but was always willing to suggest ways that they could be solved.

Madden later wrote that Nellie Bly was "full of fire and her writing was charged with youthful exuberance." However, it was not long before he was receiving complaints from those institutions that Bly was attacking in her articles. When companies began threatening to stop buying advertising space in the Pittsburgh Dispatch, the editor was forced to bring an end to the series.

Bly was now given cultural and social events to cover. Unhappy with this new job, Bly decided to go to Mexico where she wrote about poverty and political corruption. When the Mexican government discovered what Bly had been writing, they ordered her out of the country. Her account of life in Mexico was later published as Six Months in Mexico (1888). It included the followed: "The constitution of Mexico is said to excel, in the way of freedom and liberty to its subjects, that of the United States; but it is only on paper. It is a republic only in name, being in reality the worst monarchy in existence. Its subjects know nothing of the delights of a presidential campaign; they are men of a voting age, but they have never indulged in this manly pursuit, which even our women are hankering after. No two candidates are nominated for the position, but the organized ring allows one of its members - whoever has the most power - to say who shall be president."

In 1887 Bly was recruited by Joseph Pulitzer to write for his newspaper, the New York World. Over the next few years she pioneered the idea of investigative journalism by writing articles about poverty, housing and labour conditions in New York. This often involved undercover work and she feigned insanity to get into New York's insane asylum on Blackwell's Island.

Bly later wrote in Ten Days in a Mad House (1888): "Excepting the first two days after I entered the asylum, there was no salt for the food. The hungry and even famishing women made an attempt to eat the horrible messes. Mustard and vinegar were put on meat and in soup to give it a taste, but it only helped to make it worse. Even that was all consumed after two days, and the patients had to try to choke down fresh fish, just boiled in water, without salt, pepper or butter; mutton, beef, and potatoes without the faintest seasoning. The most insane refused to swallow the food and were threatened with punishment. In our short walks we passed the kitchen where food was prepared for the nurses and doctors. There we got glimpses of melons and grapes and all kinds of fruits, beautiful white bread and nice meats, and the hungry feeling would be increased tenfold. I spoke to some of the physicians, but it had no effect, and when I was taken away the food was yet unsalted."

Bly discovered while staying in the hospital that patients were fed vermin-infested food and physically abused by the staff. She also found out that some patients were not psychologically disturbed but were suffering from a physical illness. Others had been maliciously placed there by family members. For example, one woman had been declared insane by her husband after he caught her being unfaithful. Bly's scathing attacks on the way patients were treated at Blackwell's Island led to much needed reforms.

After reading Jules Verne's Around the World in Eighty Days in 1889, Bly suggested to Joseph Pulitzer that his newspaper should finance an attempt to break the record illustrated in the book. He liked the idea and used Bly's journey to publicize the New York World. The newspaper held a competition which involved guessing the time it would take Bly to circle the globe. Over 1,000,000 people entered the contest and when she arrived back in New York on 25th January, 1890, she was met by a massive crowd to see her break the record in 72 days, 6 hours, 11 minutes and 14 seconds.

Bly retired from journalism after marrying Robert Seaman in 1895. Seaman, the millionaire owner of the Iron Clad Manufacturing Company and the American Steel Barrel Company, died in 1904. Bly decided to take over the running of these two ailing companies. Recognizing the importance of the well-being of the workers, Bly introduced a series of reforms that included the provision of health-care schemes, gymnasiums and libraries.

Bly was on holiday in Europe on the outbreak of the First World War. She immediately travelled to the Eastern Front where she reported the war for the New York Journal American.

Nellie Bly died of pneumonia at St. Mark's Hospital in New York City on 27th January, 1922. She was interred at Woodlawn Cemetery in the Bronx.

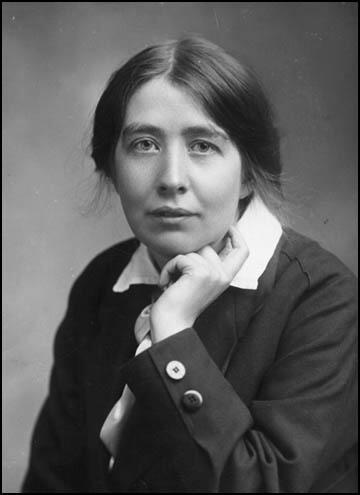

On this day in 1882 Sylvia Pankhurst, the daughter of Dr. Richard Pankhurst and Emmeline Pankhurst, was born at Drayton Terrace, Old Trafford, Manchester on 5th May, 1882. Her father was a committed socialist and a strong advocate of women's suffrage. He had been responsible for drafting an amendment to the Municipal Franchise Act of 1869 that had resulted in unmarried women householders being allowed to vote in local elections. Richard also served on the Married Women's Property Committee (1868-1870) and was the main person responsible for the drafting of the women's property bill that was passed by Parliament in 1870.

In 1886 the family moved to London where their home in Russell Square became a centre for gatherings of socialists and suffragists. They were also both members of the Fabian Society. As June Hannam has pointed out: "Sylvia's own interest in socialist and feminist politics was influenced by her parents' activities and also by the many well-known speakers and writers who visited the family." During these years Richard and Emmeline continued their involvement in the struggle for women's rights and in 1889 helped form the pressure group, the Women's Franchise League. The organisation's main objective was to secure the vote for women in local elections.

In 1893 Richard and Emmeline Pankhurst returned to Manchester where they formed a branch of the new Independent Labour Party (ILP). In the 1895 General Election, Pankhurst stood as the ILP candidate for Gorton, an industrial suburb of the city, but was defeated. Her father died of a perforated ulcer in 1898. Sylvia had been very close to her father and never really got over his death. Unlike her mother and sister, Sylvia retained the socialist beliefs that had been taught to her by her father when she was a child.

Sylvia attended Manchester Girls' High School and in 1898 began studying at Manchester Art School. In 1900 she won a scholarship to the Royal College of Art in South Kensington. Although a committed artist, Sylvia began spending more and more time working for women's suffrage.

Emmeline Pankhurst was a member of the Manchester National Society for Women's Suffrage. By 1903 Pankhurst had become frustrated at the NUWSS lack of success. With the help of her three daughters, Sylvia, Christabel Pankhurst and Adela Pankhurst, she formed the Women's Social and Political Union (WSPU). At first the main aim of the organisation was to recruit more working class women into the struggle for the vote. At first members of the WSPU were drawn largely from the Independent Labour Party and carried out propaganda for both socialism and women's suffrage in the north of England.

By 1905 the media had lost interest in the struggle for women's rights. Newspapers rarely reported meetings and usually refused to publish articles and letters written by supporters of women's suffrage. In 1905 the WSPU decided to use different methods to obtain the publicity they thought would be needed in order to obtain the vote.

On 13th October 1905, Christabel Pankhurst and Annie Kenney attended a meeting in London to hear Sir Edward Grey, a minister in the British government. When Grey was talking, the two women constantly shouted out, "Will the Liberal Government give votes to women?" When the women refused to stop shouting the police were called to evict them from the meeting. Pankhurst and Kenney refused to leave and during the struggle a policeman claimed the two women kicked and spat at him. Pankhurst and Kenney were arrested and charged with assault.

Christabel Pankhurst and Annie Kenney were found guilty of assault and fined five shillings each. Kenney and Pankhurst were found guilty of assault and fined five shillings each. When the women refused to pay the fine they were sent to prison. The case shocked the nation. For the first time in Britain women had used violence in an attempt to win the vote.

In 1906 Sylvia gave up her studies at the Royal College of Art and worked full-time for the WSPU. Later that year she suffered her first imprisonment after protesting in court at a trial in which women had not been allowed to speak in their own defence.

Sylvia was also very active in the Labour Party and became a close friend of Keir Hardie, the leader of the party in the House of Commons. According to the author of Freedom's Cause: Lives of the Suffragettes (2003): "The young student, now aged twenty-four, had fallen for the fifty-year-old politician in a manner which went far beyond mere admiration or friendship. As the relationship developed, the complexity of these feelings became clearer. Sylvia saw Hardie as part political hero, part father-figure and part potential lover. Gradually he began to return her feelings... Hardie helped her move into cheaper lodgings, soothed her furrowed brow and took her out for a cheering meal. From then on Sylvia often visited him at the House of Commons and the two walked together in St James's Park or spent the evening at Nevill's Court. Quite how they dealt with the fact that he was already married is not entirely clear."

During the summer of 1908 the WSPU introduced the tactic of breaking the windows of government buildings. On 30th June suffragettes marched into Downing Street and began throwing small stones through the windows of the Prime Minister's house. As a result of this demonstration, twenty-seven women were arrested and sent to Holloway Prison.

On 25th June 1909 Marion Wallace-Dunlop was charged "with wilfully damaging the stone work of St. Stephen's Hall, House of Commons, by stamping it with an indelible rubber stamp, doing damage to the value of 10s." Wallace-Dunlop was found guilty of wilful damage and when she refused to pay a fine she was sent to prison for a month. Christabel Pankhurst later reported: "Miss Wallace Dunlop, taking counsel with no one and acting entirely on her own initiative, sent to the Home Secretary, Mr. Gladstone, as soon as she entered Holloway Prison, an application to be placed in the first division as befitted one charged with a political offence. She announced that she would eat no food until this right was conceded." Wallace-Dunlop refused to eat for several days. Afraid that she might die and become a martyr, it was decided to release her after fasting for 91 hours. Soon afterwards other imprisoned suffragettes adopted the same strategy. Unwilling to release all the imprisoned suffragettes, the prison authorities force-fed these women on hunger strike.

In 1909 Sylvia and Keir Hardie rented a cottage in Penshurst, Kent. They met there as often as his busy schedule permitted. According to Fran Abrams: "During one of these interludes he begged her not to go back to prison. The thought of the feeding tubes and the violence with which they were used was already making him ill - how much worse would it be if it were her?"

Sylvia Pankhurst became concerned about the increase in the violence used by the Women's Social and Political Union. This view was shared by her younger sister, Adela Pankhurst. She later told fellow member, Helen Fraser: "I knew all too well that after 1910 we were rapidly losing ground. I even tried to tell Christabel this was the case, but unfortunately she took it amiss." After arguing with Emmeline Pankhurst about this issue she left the WSPU.

Sylvia was a talented writer and in 1911 her book The History of the Women's Suffrage Movement was published. However, Sylvia was unhappy that the WSPU had abandoned its earlier commitment to socialism and disagreed with Emmeline and Christabel Pankhurst's attempts to gain middle class support by arguing in favour of a limited franchise.

In the spring of 1913 Sylvia Pankhurst was arrested three times. As Fran Abrams has pointed out: "On the first two occasions her efforts were thwarted when her fines were paid and she was released - the first time she blamed WSPU officials, the second time her mother. Finally, in February, she managed to get a two-month sentence and went on hunger strike. She was force fed, then released on Good Friday in a terrible state. Her eyes blood red, almost unable to walk, she was taken to a WSPU nursing home where Hardie found her a few hours later.... Back in prison again in July, she refused food, drink and sleep. Now she was placed under the Cat and Mouse Act, repeatedly released and then rearrested."

However, Sylvia was growing disillusioned by the WSPU new arson campaign. In July, 1913, attempts were made by suffragettes to burn down the houses of two members of the government who opposed women having the vote. These attempts failed but soon afterwards, a house being built for David Lloyd George, the Chancellor of the Exchequer, was badly damaged by suffragettes. This was followed by cricket pavilions, racecourse stands and golf clubhouses being set on fire.

Some leaders of the WSPU such as Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence, disagreed with this arson campaign. When Pethick-Lawrence objected, she was expelled from the organisation. Others like Elizabeth Robins showed their disapproval by ceasing to be active in the WSPU. Sylvia now made her final break with the WSPU and concentrated her efforts on helping the Labour Party build up its support in London.

In 1913, Pankhurst, with the help of Keir Hardie, Julia Scurr, Mary Phillips, Millie Lansbury, Eveline Haverfield, Maud Joachim, Lilian Dove-Wilcox, Jessie Stephen, Nellie Cressall and George Lansbury, established the East London Federation of Suffragettes (ELF). An organisation that combined socialism with a demand for women's suffrage it worked closely with the Independent Labour Party. Pankhurst also began production of a weekly paper for working-class women called The Women's Dreadnought. As June Hannam has pointed out: "The ELF was successful in gaining support from working women and also from dock workers. The ELF organized suffrage demonstrations and its members carried out acts of militancy. Between February 1913 and August 1914 Sylvia was arrested eight times. After the passing of the Prisoners' Temporary Discharge for Ill Health Act of 1913 (known as the Cat and Mouse Act) she was frequently released for short periods to recuperate from hunger striking and was carried on a stretcher by supporters in the East End so that she could attend meetings and processions. When the police came to re-arrest her this usually led to fights with members of the community which encouraged Sylvia to organize a people's army to defend suffragettes and dock workers. She also drew on East End traditions by calling for rent strikes to support the demand for the vote."

On 4th August, 1914, England declared war on Germany. Two days later the NUWSS announced that it was suspending all political activity until the war was over. The leadership of the WSPU began negotiating with the British government. On the 10th August the government announced it was releasing all suffragettes from prison. In return, the WSPU agreed to end their militant activities and help the war effort.

Emmeline Pankhurst announced that all militants had to "fight for their country as they fought for the vote." Ethel Smyth pointed out in her autobiography, Female Pipings for Eden (1933): "Mrs Pankhurst declared that it was now a question of Votes for Women, but of having any country left to vote in. The Suffrage ship was put out of commission for the duration of the war, and the militants began to tackle the common task."

Annie Kenney reported that orders came from Christabel Pankhurst: "The Militants, when the prisoners are released, will fight for their country as they have fought for the Vote." Kenney later wrote: "Mrs. Pankhurst, who was in Paris with Christabel, returned and started a recruiting campaign among the men in the country. This autocratic move was not understood or appreciated by many of our members. They were quite prepared to receive instructions about the Vote, but they were not going to be told what they were to do in a world war."

After receiving a £2,000 grant from the government, the WSPU organised a demonstration in London. Members carried banners with slogans such as "We Demand the Right to Serve", "For Men Must Fight and Women Must work" and "Let None Be Kaiser's Cat's Paws". At the meeting, attended by 30,000 people, Emmeline Pankhurst called on trade unions to let women work in those industries traditionally dominated by men.

Sylvia Pankhurst was a pacifist and disagreed with the WSPU's strong support for the war. In 1915 she joined with Charlotte Despard, Helena Swanwick, Olive Schreiner, Helen Crawfurd, Alice Wheeldon, Hettie Wheeldon, Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence and Chrystal Macmillan to form the Women's Peace Army, an organisation that demanded a negotiated peace.

During the war Sylvia joined with Dr. Barbara Tchaykovsky to open four mother-and-baby clinics in London. Tchaykovsky pointed out that during the first year of the war 75,000 British soldiers (2.2 per cent of the combatants) had been killed. However, during the same period over 100,000 babies in Britain (12.2 per cent of those born) had died. In 1915 nearly 1,000 mothers and their babies were seen at Sylvia's clinics. Local politicians such as George Lansbury helped to raise funds for the organisation that's milk bill alone was over £1,000 a year.

In March 1916 Pankhurst renamed the East London Federation of Suffragettes, the Workers' Suffrage Federation (WSF). The newspaper was renamed the Workers' Dreadnought and continued to campaign against the war and gave strong support to organizations such as the Non-Conscription Fellowship. The newspaper also published the famous anti-war statement in July, 1917, by Siegfried Sassoon.

Sylvia Pankhurst was a supporter of the Russian Revolution in 1917 and visited the country where she met Lenin and ended up arguing with him over the issue of censorship. The government disliked Sylvia's pro-Communist articles in her newspaper and she was imprisoned for five months for sedition. After she was released from prison Pankhurst renamed her organization the Workers' Socialist Federation.

On 31st July, 1920, a group of revolutionary socialists attended a meeting at the Cannon Street Hotel in London. The men and women were members of various political groups including the British Socialist Party (BSP), the Socialist Labour Party (SLP), Prohibition and Reform Party (PRP) and the Workers' Socialist Federation (WSF).

It was agreed to form the Communist Party of Great Britain (CPGB). Early members included Tom Bell, Willie Paul, Arthur McManus, Harry Pollitt, Rajani Palme Dutt, Helen Crawfurd, A. J. Cook, Albert Inkpin, J. T. Murphy, Arthur Horner, John R. Campbell, Bob Stewart and Robin Page Arnot. McManus was elected as the party's first chairman and Bell and Pollitt became the party's first full-time workers. It later emerged that Lenin had provided at least £55,000 (over £1 million in today's money) to help fund the CPGB.

Sylvia Pankhurst considered the CPGB to be too right-wing and was completely opposed to the idea of it being affiliated to the Labour Party. She was eventually expelled from the CPGB for refusing to allow the Dreadnought from being controlled by the party executive. The Workers' Socialist Federation was closed down in June 1924.

Sylvia began living with Silvio Erasmus Corio (1875–1954), an Italian socialist. They moved to Woodford Green and in 1927, at the age of forty-five, she gave birth to her only child, Richard Keir Pethick Pankhurst. The boy was named after the three most important men in her life: Richard Pankhurst, Keir Hardie and Frederick Pethick-Lawrence. Sylvia upset Emmeline Pankhurst and Christabel Pankhurst, by refusing to marry the boy's father. As her biographer, June Hannam, has pointed out: "She had long believed in sexual freedom and, despite pressure from Christabel, lived out her ideas in practice by refusing to marry."

During this period she wrote several books, including India and the Earthly Paradise (1926), a book calling on the reform of maternity care, Save the Mothers (1930), a history of the struggle for the vote, The Suffrage Movement (1931) and an account of her war experiences in the East End, The Home Front (1932).

Sylvia remained active in politics throughout her life. In the 1930s she supported the republicans in Spain, helped Jewish refugees from Nazi Germany and led the campaign against the Italian occupation of Ethiopia. In 1935 she began a weekly journal, The Ethiopian News, that publicized the efforts made by Emperor Haile Selassie to persuade the League of Nations to prevent colonization.

The British secret service had held a file on Sylvia Pankhurst since her early days in the suffrage movement. However as late as 1948 MI5 was considering various strategies for "muzzling the tiresome Miss Sylvia Pankhurst."

In 1953 Sylvia suffered a heart-attack. As a result, her sister, Christabel Pankhurst made contact with Sylvia. As June Purvis has pointed out: "On 5 May 1953, Sylvia's birthday, Christabel renewed contact with her sister, writing her a warm letter and wishing her well after her recent heart attack. The correspondence between the two sisters continued intermittently until Christabel's death."

After Silvio Erasmus Corio died in 1954 Sylvia accepted an earlier invitation from the Emperor Haile Selassie and moved with her son to live permanently in Ethiopia in 1956. She helped to found the Social Service Society and edited a monthly periodical, the Ethiopia Observer. In 1959 an exhibition of her art was held at the French Institute in London

Sylvia Pankhurst died in Addis Ababa, on 27 September 1960. She was regarded so highly in Ethiopia that the emperor ordered that she should receive a state funeral, which was attended by himself and other members of the royal family. A memorial service was held in London in the Caxton Hall on 19th January 1961.

Emmeline Pankhurs and Christabel Pankhurst have both been commemorated by a statue and plaque at the entrance to Victoria Tower Gardens on the corner of the House of Commons. Over the years the House of Lords has repeatedly blocked proposals for a memorial to Sylvia Pankhurst.

The Observer reported on 6th March, 2016 that the TUC and City of London Corporation are to launch a joint campaign to erect a statue of Sylvia on Clerkenwell Green in Islington in time for the centenary of the Representation of the People Act 1918, which first gave the vote to some women.

On this day in 1934 civil rights activist Charles Houston makes important speech in at the National YWCA Convention, Philadelphia:

The race problem in the United States is the type of unpleasant problem which we would rather do without but which refuses to be buried. It has been a visible or invisible factor in almost every important question of domestic policy since the foundation of the Government, and may yet be the decisive factor in the success or failure of the New Deal. The dominant interests in the South are determined that there shall not be an industrial emancipation of the Negro. In Birmingham, Alabama, on April 18, one brass-lunged industrialist raised the threat of secession of the Government persisted in its efforts to eliminate the wage differentials between the North and South....

In the field of agriculture the government cotton acreage reduction program of 1933 brought a conflict in interest between the plantation owners and their predominantly Negro sharecroppers and tenant farmers. The Southern Commission on the Study of Lynching in its report "The Plight of Tuscaloosa", found that out of 6,000 government checks sent into Tuscaloosa County, Alabama, as compensation for the cotton acreage reduction, only 115 were made out to Negroes; and even then informed local people knew of no instance in which a Negro got any of the money, their checks being endorsed over to white men in every known instance. The significance of this condition is too plain for argument when one realizes that Negroes constitute more than 70% of the dirt cotton farmers in Tuscaloosa County, and when one considers that the New Deal was intended to reach all the way down and benefit the man actually on the soil. It remains to be seen whether the Bankhead Act will give the 'croppers any better protection in 1934.

The Scottsboro Cases, the Angelo Herndon Case in Georgia, the impotence of the States to curb or punish lynching; the attempted murder of two Negro lawyers near Henderson, North Carolina, for daring to challenge the exclusion of Negroes from a North Carolina jury, reflect the load carried by the Negro in the courts of "justice"?

In the field of government you must know how the Federal Civil Service rules requiring candidates to state their race and submit their photograph with their application have been used to eliminate Negroes as a class from all appointments covered by civil service above the grades of laborer or messenger. An obstinate policy of the War and Navy Departments has decimated the ranks of Negro soldiers and sailors, and effectively emasculated those still left in the service of most of their self-respect; a matter which I predict the United States will seriously regret in the event of another war. You must know something of the humiliation and procrastination which Negro white collar workers met in many sections last winter when they applied for work under the CWA. The newspapers have been full of the DePriest resolution against racial discrimination in the House Restaurant in Washington, and the assault on a cultured Negro woman for the sole offense that she was hungry and tried to get service in the Senate restaurant during the hearings on the Costigan-Wagner Anti-Lynching Bill.

The plight of the Negro worker in agriculture, domestic service and industry; the disproportionate number of Negro families on relief due to job displacements and other loss of work, with attendant loss of self-assurance, are open sores calling for social surgery of the highest order. But there is no use piling up the deficit.

On the credit side we can point to certain advances. The Negro has made some progress under the New Deal; and at least in the Federal Government there is an increasing tendency to give him a voice in his own interest and to include his requirements in the national recovery. The Attorney General of Ohio has just overthrown the designation of race and use of photograph in the Ohio State Civil Service applications by declaring it an unconstitutional discrimination. The State of Maryland in 1933 made a bold attempt to bring the lynchers of George Armwood to justice. The Commonwealth of Virginia is reforming its jury system. Southern women are moving rapidly to the front in interracial work. And your own Association has exhibited significant liberal tendencies.

On this day in 1935 Vito Marcantonio explains why he is against political deportations. "I do not believe in the deportation of any man or woman because of the political principles that they hold. Irrespective of what a person advocates, he or she should not be molested, because our Government has been based upon the principles of freedom of speech, freedom of the press, freedom of religion and freedom of thought. I disagree with the Communists. I emphatically do not agree with them, but they have a perfect right to speak out and to advocate communism. I maintain that the moment we deprive those with whom we extremely disagree of their right to freedom of speech, the next thing that will happen is that our own right of freedom of speech will be taken away from us. Freedom of speech, if it means anything, means freedom of speech for everyone and not for only those who agree with us or who are in the majority. The founders of our Nation intended freedom of speech to mean freedom of speech for all, especially for the smaller minorities. They keenly felt the necessity for this protection. They had been persecuted by Tories and reactionaries. Then they were called "rebels" and hounded by bigots and suppressionists of that day. Today the brothers of the Tories of 1776 would abolish what the rebels of 1776 have given us - freedom of speech."

Vito Marcantonio, the son of Italian immigrants, was born in East Harlem, New York City on 10th December, 1902. He attended De Witt Clinton High School where he came under the influence of Fiorello La Guardia: "He addressed the school assembly the same day when I made a speech. I shall never forget it. I spoke in favor of old-age pensions and social security. La Guardia made this the theme of his speech to the students."

Marcantonio was a successful student and despite his poor background eventually managed to enter New York University Law School. While at university Marcantonio became involved in politics. In 1924 he joined Fiorello La Guardia in supporting Robert La Follette, who was the presidential candidate of the Progressive Party. This resulted in La Guardia losing the Republican Party nomination. "The Democratic Party, as usual, sought to defeat him. La Guardia asked me to actively participate in that campaign, and together with a handful of our friends and neighbors in East Harlem, we conducted a successful campaign for him and for LaFollette in our congressional district."

In 1926 Marcantonio was admitted to the bar and worked as a lawyer in New York City and served as assistant United States district attorney (1930-31). In 1933 Marcantonio played an important role in the successful election campaign of Fiorello La Guardia as mayor of New York City. Seen as La Guardia's heir apparent, Marcantonio was elected to Congress in 1934 where he represented East Harlem's 20th District.

In Congress he argued against the policy of deporting people like Emma Goldman for their left-wing views: "I do not believe in the deportation of any man or woman because of the political principles that they hold. Irrespective of what a person advocates, he or she should not be molested, because our Government has been based upon the principles of freedom of speech, freedom of the press, freedom of religion and freedom of thought."

Marcantonio was accused of being a secret supporter of the American Communist Party. He replied: "I disagree with the Communists. I emphatically do not agree with them, but they have a perfect right to speak out and to advocate communism. I maintain that the moment we deprive those with whom we extremely disagree of their right to freedom of speech, the next thing that will happen is that our own right of freedom of speech will be taken away from us."

An outspoken politician with left-wing views, Marcantonio was defeated in 1936 but won the seat back in 1938 as the American Labor Party candidate. A strong supporter of Franklin D. Roosevelt and the New Deal, Marcantonio held the seat for the next twelve years. In Congress he argued that the "unemployed are victims of an unjust economic and social system which has failed." Marcantonio was also a strong supporter of African American Civil Rights.

As Gerald Meyer has pointed out: "In the House, Marcantonio distinguished himself as the major leader for civil rights legislation by sponsoring anti-lynching and anti-poll tax bills as well as the annual fight for the Fair Employment Practices Commission's appropriation. He served as de facto congressperson for Puerto Rico, insuring that it was not excluded from appropriations bills. He also submitted five bills calling for the independence of Puerto Rico (which he called "the greatest victim of United States imperialism") with an indemnity for the damage done to the island by the United States business interests which had replaced tens of thousands of small farms with sugar plantations."

Marcantonio was a fierce critic of Martin Dies and his Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC) that was established in 1937. The main objective of the HUAC was the investigation of un-American and subversive activities. This included looking at the possibility that the American Communist Party had infiltrated the Federal Writers Project and other New Deal projects. In 1940 Marcantonio argued: "If communism is destroyed, I do not know what some of you will do. It has become the most convenient method by which you wrap yourselves in the American flag in order to cover up some of the greasy stains on the legislative toga. You can vote against the unemployed, you can vote against the W.P.A. workers, and you can emasculate the Bill of Rights of the Constitution of the United States; you can try to destroy the National Labor Relations Law, the Magna Carta of American labor; you can vote against the farmer; and you can do all that with a great deal of impunity, because after you have done so you do not have to explain your vote.

Marcantonio was against United States involvement in the early stages of the Second World War because he believed it was "a war between two axes, the Wall Street-Downing Street Axis versus the Rome-Tokyo-Berlin Axis, contending for empire and for exploitation of more and more people." However, after the bombing of Pearl Harbor he played an active role in the American Committee for Russian War Relief. Along with Fiorello La Guardia, Charlie Chaplin, Wendell Willkie, Orson Welles, Rockwell Kent and Pearl Buck, Marcantonio campaigned during the summer of 1942 for the opening of a second-front in Europe.

In 1944 a New York State re-districting made possible a new attempt to defeat him by removing part of his old district and adding to the new 18th Congressional District. As Harpers Magazine pointed out: "The Twentieth Congressional District no longer exists. the New York Legislature, dominated by upstate Republicans who have nothing to fear from Marcantonio, has reapportioned the state and tried to gerrymander Marcantonio out of office. In the new Eighteenth District, he will still have most of his East Harlem Spaniards and Italians but life will be complicated by the addition of vast German and Irish hordes from the adjoining Yorkville area." Despite these attempts to remove him, he carried the district by a majority of 66,390.

In 1946, the media did everything it could to defeat Marcantonio and the American Labor Party in East Harlem. Despite the smear campaign he still won by 5,500 votes. As Sidney Shallet pointed out: "What matters to them is not whether Marcantonio is red, pink, black, blue or purple, but that he is 'their' Congressman a... tireless fighter for the man on the streets of East Harlem. He is willing to live in their slums, rub elbows with the best and the worst of them, work himself to the thin end of a frazzle for them. He spends his dough on them, takes up their battles against the landlords.... On occasions... the Congressman even has carried scuttles of coal personally to heatless tenements. Anyone who wants to see him... can do so."

Richard Rovere described the work of Marcantonio after his election: "The scene in the La Guardia Club after one o'clock on Sunday looks like nothing so much as a busy day in the clinic of a great city hospital. Marcantonio and three or four secretaries sit at desks on a platform in the front of the main hall. Before them on wooden camp chairs are about a hundred constituents, many of them cradling infants in their arms... as many as four hundred may come and go in an afternoon.... They speak in Spanish, Italian, English, and various mixtures of the three. Marcantonio can always answer in kind, throwing in a little Yiddish if the need arises. Mostly their problems concern money or jobs."

Along with his colleague, Leo Isacson, Marcantonio campaigned for equality in the armed forces. When Eugene Hoffman of Mitchigan argued against this move, Marcantonio pointed out: " The doctrine that has been advanced here by the gentleman from Michigan is a doctrine of insult to the various races that compose this great nation. When he speaks of an inferior race, what is it? When he speaks of a superior race, what is it? Contemporary history has demonstrated conclusively that only Nazis, those who imposed on this world the most barbarian rule ever conceived by man or devil, were capable of talking of superior races or inferior races or of denouncing the intermingling of races."

Vito Marcantonio joined forces with Emanuel Celler to argue against the formation of the Central Intelligence Agency. "With all of the vast powers that are given this agency under the guise of research and study, you are subjecting labor unions and business firms to the will of the military. You are opening the door for the placing of these intelligence agents, supposed to deal with security pertaining to foreign as well as internal affairs, in the midst of labor organizations... I am sure if it were not for the cold war hysteria, very few Members of the Congress would vote for that provision. Certainly the majority would not vote to suspend the rules so that you must take this bill as it is without any opportunity for amendment, despite its serious implications against the security of the liberties of the American people."

On the morning of 20th July, 1948, Eugene Dennis, the general secretary of the American Communist Party and eleven other party leaders, including John Gates, William Z. Foster, Benjamin Davis, Robert G. Thompson, Gus Hall, Benjamin Davis, Henry M. Winston, and Gil Green were arrested and charged under the Alien Registration Act. This law, passed by Congress in 1940, made it illegal for anyone in the United States "to advocate, abet, or teach the desirability of overthrowing the government".

Vito Marcantonio decided to help with their political defence. During this period of McCarthyism, this was political suicide. As one political commentator pointed out: "Marcantonio's opposition in the 81st Congress to both major parties on such fundamental issues as foreign policy, labor relations and civil liberties had become so outstanding that extraordinary measures were taken to prevent his reelection. A three party coalition of the Democratic, Republican and Liberal parties, supported by every major newspaper in New York City, backed a single candidate against him." The New York Times ran a series of editorials on three successive days urging his defeat. Even so, Marcantonio still won over 40% of the votes in the 18th congressional district.

After his defeat he maintained his two neighborhood offices so the people of East Harlem could still visit him to gain help with their problems. Marcantonio remained one of the strongest opponents of Joe McCarthy and the Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC) and was legal counsel of civil rights activist, William Du Bois.

Marcantonio was also opposed to the Korean War: "Tragically, after 27 months of killing in Korea, with 119,000 American casualties, some of us accept the Korean conflict as we do the flowing of the Hudson River. After 14 months of talk at Panmunjom some have come to feel that this so-called police action or little war is something with which we can live. They have forgotten that war in our time is like cancer if it is not stopped it spreads. If this Korean war is not stopped now, it too will spread... The resolving of every other issue, civil rights, labor, civil liberties, agriculture, the economic well-being of the American people, depends on cease fire in Korea."

In 1952 Presidential Election Marcantonio supported Vincent Hallinan, the leader of the Progressive Party. "A vote for the Progressive Party in 1952... is a vote as valuable as that cast for the Liberty Party in 1840 against slavery, and for the Free Soil Party in 1848 and 1852 against extension of slavery. It is a vote similar to the one that made up the one million votes for Eugene V. Debs in 1920, which in turn led to the four million votes for LaFollette in 1924 and for victory for Roosevelt in 1932. Great causes were never won by sacrificing a real fight and substituting for it the seeming lesser evil."

In 1953 Marcantonio decided to resign from the American Labor Party and to campaign for his old seat as an independent: "I shall continue to strive as an independent for the things for which I have striven so hard. I shall continue to do so as an independent endeavoring for the political realignment which is inevitable. It is as inevitable as the failure of the Republican and Democrat foreign policy and the economy that is based upon it."

Vito Marcantonio, who practiced law until his death of a heart attack on 9th August, 1954. Probably the most left-wing person to hold a seat in Congress, over 20,000 people attended Marcantonio's funeral in New York City.

On this day in 1956 Joseph Mallalieu in The New Stateman publishes article on Sydney Silverman: "Of all the House of Commons personalities, the most irritating is perhaps Mr Sydney Silverman. He is a cocky man, who throws his shoulders back as if to swell his chest, and thrusts his now bearded chin outward and upward, as if to give him inches. Indeed, he seems over-occupied with his own shortness. As a result even his jokes are often outsize, and he follows them with an extravagant cackle, slapping his knee in an ecstasy of delight. Often the point of these stories is that some body, corporate or otherwise and very likely the National Executive of the party, has been scored off by him.... This might merely suggest that he is a good lawyer; but there is much more to him than the bare ability to argue technical points. Coming from a large and not particularly well-to-do Liverpool Jewish family, he had to fight for his own legal education through scholarships. When he did begin to practise, he had just sufficient money to open an office and pay a typist one week's wages. But within a short time he was perhaps the most active, and certainly one of the more successful, solicitors in Liverpool. This success was only partly due to his forensic ability in the police courts. Even more, it was due to his passion for what he believes to be right, and to his bias for believing that right is more likely to be on the side of the little man than of the mighty."