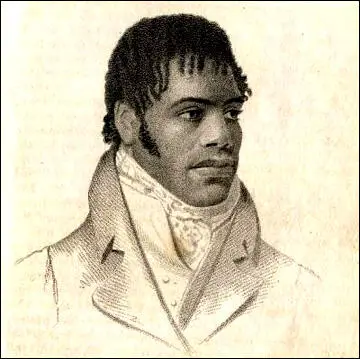

William Davidson

William Davidson, was born in Jamaica in 1781. The illegitimate son of the Jamaican Attorney General and a local black woman, William was sent to Glasgow at the age of fourteen to study law. While in Scotland he became involved in the demand for parliamentary reform. Davidson was apprenticed to a Liverpool lawyer but after three years ran away to sea. Later he was impressed into the Royal Navy.

On his discharge he returned to Scotland and his father sent him to study mathematics in Aberdeen. Davidson did not enjoy his studies and moved to Birmingham where he started a cabinet-making business. Davidson fell in love with the daughter of a prosperous merchant. The father disapproved of his daughter's relationship and suspected that Davidson was after her £7,000 dowry and arranged for him to be arrested on a false charge. When he discovered she had married someone else he tried to kill himself by taking poison.

After the failure of his cabinet-making business William Davidson moved to London. He married Sarah Lane, a working-class widow with four children. In the next few years she had two more. Davidson became a Wesleyan Methodist and taught at the local Sunday School. This came to an end when he was accused of attempting to seduce a female student.

William Davidson became involved in radical politics again after the Peterloo Massacre. After Richard Carlile was found guilty of blasphemy and seditious libel and sentenced to three years imprisonment in October 1819, Davidson told a friend that these events had caused him to lose his belief in God. Davidson now joined the Marylebone Union Reading Society where for twopence a week he was able to read radical newspapers such as the Republican and the Manchester Observer. He also read the works of Tom Paine.

It was at the Marylebone Union that Davidson met John Harrison, a member of the Spencean Philanthropists in London. Soon afterwards Davidson also became a Spencean. He met Arthur Thistlewood and within a few months became one of the Committee of Thirteen that ran the organisation.

On 22nd February 1820, George Edwards (a government spy) pointed out to Arthur Thistlewood an item in the New Times that several members of the British government were going to have dinner at Lord Harrowby's house at 39 Grosvenor Square. William Davidson agreed to join Thistlewood and and twenty-seven other Spenceans in the plot to kill the government ministers dining at Lord Harrowby's house on 23rd February. Thistlewood selected Davidson as one of the Executive of Five whose job it was to organise the assassinations.

Davidson had worked for Lord Harrowby in the past and knew some of the staff that worked at Grosvenor Square. He was instructed to find out more details about the cabinet meeting. However, when he spoke to one of the servants he was told that the Earl of Harrowby was not in London. When Davidson reported this news back to Arthur Thistlewood he insisted that the servant was lying and that the assassinations should proceed as planned.

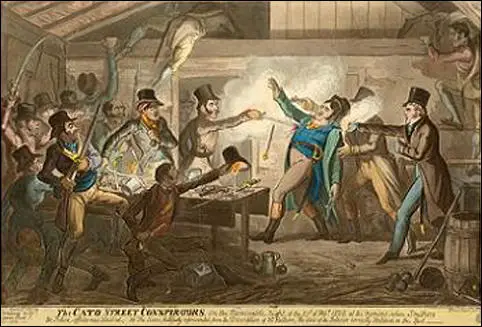

On the 23rd February Thistlewood's gang assembled in a hayloft in Cato Street, a short distance away from Grosvenor Square. However, government ministers were not meeting at the home of Earl of Harrowby. The Spenceans had been set up by George Edwards, a government spy who had infiltrated the Spencean Society.

Thirteen police officers led by George Ruthven stormed the hay loft. Several members of the gang refused to surrender their weapons and one police officer, Richard Smithers, was killed by Arthur Thistlewood. Davidson attempted to fight his way out but Benjamin Gill hit him on the wrist with his truncheon and he dropped his blunderbuss. Four of the conspirators, Thistlewood, John Brunt, Robert Adams and John Harrison escaped out of a window. However, George Edwards had given the police a detailed list of all those involved and the men were soon arrested.

Eleven men were eventually charged with being involved in the Cato Street Conspiracy. Charges against Robert Adams were dropped when he agreed to give evidence against the other men in court. Davidson claimed he was innocent and accused the court of being prejudiced against black people. However, not only had Davidson been arrested at the scene but evidence was produced to show that he had taken a blunderbuss out of pawn to use in the attempted assassinations.

Davidson said in court: "It is an ancient custom to resist tyranny... And our history goes on further to say, that when another of their Majesties the Kings of England tried to infringe upon those rights, the people armed, and told him that if he did not give them the privileges of Englishmen, they would compel him by the point of the sword... Would you not rather govern a country of spirited men, than cowards? I can die but once in this world, and the only regret left is, that I have a large family of small children, and when I think of that, it unmans me."

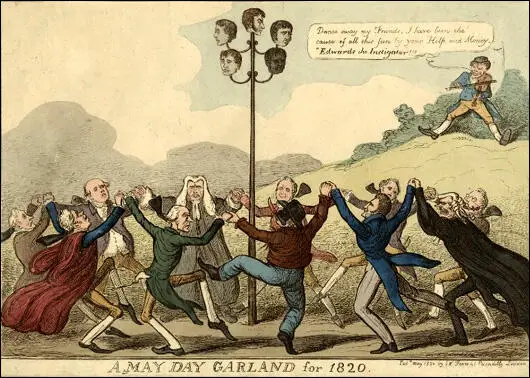

On 28th April 1820, William Davidson, James Ings, Richard Tidd, Arthur Thistlewood, and John Brunt were found guilty of high treason and sentenced to death. John Harrison, James Wilson, Richard Bradburn, John Strange and Charles Copper were also found guilty but their original sentence of execution was subsequently commuted to transportation for life. William Davidson was executed at Newgate Prison on the 1st May, 1820.

William Davidson, James Ings, Richard Tidd, Arthur Thistlewood and John Brunt (May 1820)

Primary Sources

(1) Willliam Davidson, speech in court (April, 1820)

It is an ancient custom to resist tyranny... And our history goes on further to say, that when another of their Majesties the Kings of England tried to infringe upon those rights, the people armed, and told him that if he did not give them the privileges of Englishmen, they would compel him by the point of the sword... Would you not rather govern a country of spirited men, than cowards? I can die but once in this world, and the only regret left is, that I have a large family of small children, and when I think of that, it unmans me.

(2) British Luminary and Weekly Intelligence (7th May, 1820)

Davidson ascended the scaffold with a firm step, calm deportment, and undismayed countenance. He bowed to the crowd, but his conduct altogether was equally free from the appearance of terror, and the affectation of indifference.

(3) John Hobhouse observed the executions and that night wrote about it in his diary (1st May, 1820)

The men died like heroes. Ings, perhaps, was too obstreperous in singing 'Death or Liberty', and Thistlewood said, "Be quiet, Ings; we can die without all this noise."

(4) The Traveller (May, 1820)

The executioner, who trembled much, was a long time tying up the prisoners; while this operation was going on a dead silence prevailed among the crowd, but the moment the drop fell, the general feeling was manifested by deep sighs and groans. Ings and Brunt were those only who manifested pain while hanging. The former writhed for some moments; but the latter for several minutes seemed, from the horrifying contortions of his countenance, to be suffering the most excruciating torture.

(5) George Theodore Wilkinson, An Authentic History of the Cato Street Conspiracy (1820)

Thistlewood struggled slightly for a few minutes, but each effort was more faint than that which preceded; and the body soon turned round slowly, as if upon the motion of the hand of death.

Tidd, whose size gave cause to suppose that he would "pass" with little comparative pain, scarcely moved after the fall. The struggles of Ings were great. The assistants of the executioner pulled his legs with all their might; and even then the reluctance of the soul to part from its native seat was to be observed in the vehement efforts of every part of the body. Davidson, after three or four heaves, became motionless; but Brunt suffered extremely, and considerable exertions were made by the executioners and others to shorten his agonies.

(6) Richard Carlile, letter to Sarah Davidson (May 1820)

Little did I think that villain Edwards was the spy, agent, and instigator of the government, and Mr. Davidson his victim. I now regret my error, and hope that you will pardon it as an error of the head, without any bad motive. Be assured that the heroic manner in which your husband and his companions met their fate, will in a few years, perhaps in a few months, stamp their names as patriots, and men who had nothing but their country's weal at heart. I flatter myself as your children grow up, they will find that the fate of their father will rather procure them respect and admiration than its reverse.