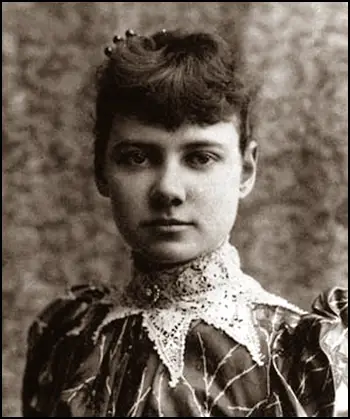

Nellie Bly

Elizabeth Cochrane was born in Cochran Mills, Allegheny County, Pennsylvania, on 5th May, 1864. Her father died six years later, leaving her mother, Mary Jane Cochrane, with fifteen children to raise. Elizabeth was not an impressive student at school but she did develop a strong desire to be a writer.

The family were fairly poor and when Elizabeth reached sixteen she moved to Pittsburgh to find work. She soon discovered that only low-paid occupations were available to women. In 1885 she read an article in the Pittsburgh Dispatch entitled What Girls Are Good For. The male writer argued that women were only good for housework and taking care of children. Elizabeth was furious and wrote a letter of protest to the editor. George Madden responded by asking her what articles she would write if she was a journalist. She replied that newspapers should be publishing articles that told the stories of ordinary people. As a result of her letter, Madden commissioned Elizabeth, who was only eighteen, to write an article on the lives of women.

Elizabeth accepted, but as it was considered improper for at the time for women journalists to use their real names, she used a pseudonym: Nellie Bly. She decided to write an article on divorce based on interviews with women that she knew. In the piece, Bly used the material to argue for the reform of the marriage and divorce laws. Madden was so impressed with the article he hired her as a full-time reporter for the Pittsburgh Dispatch. Bly's journalistic style was marked by her first-hand tales of the lives of ordinary people. She often obtained this material by becoming involved in a series of undercover adventures. For example, she worked in a Pittsburgh factory to investigate child labour, low wages and unsafe working conditions. Bly was not only interested in writing about social problems but was always willing to suggest ways that they could be solved.

Madden later wrote that Nellie Bly was "full of fire and her writing was charged with youthful exuberance." However, it was not long before he was receiving complaints from those institutions that Bly was attacking in her articles. When companies began threatening to stop buying advertising space in the Pittsburgh Dispatch, the editor was forced to bring an end to the series.

Bly was now given cultural and social events to cover. Unhappy with this new job, Bly decided to go to Mexico where she wrote about poverty and political corruption. When the Mexican government discovered what Bly had been writing, they ordered her out of the country. Her account of life in Mexico was later published as Six Months in Mexico (1888). It included the followed: "The constitution of Mexico is said to excel, in the way of freedom and liberty to its subjects, that of the United States; but it is only on paper. It is a republic only in name, being in reality the worst monarchy in existence. Its subjects know nothing of the delights of a presidential campaign; they are men of a voting age, but they have never indulged in this manly pursuit, which even our women are hankering after. No two candidates are nominated for the position, but the organized ring allows one of its members - whoever has the most power - to say who shall be president."

In 1887 Bly was recruited by Joseph Pulitzer to write for his newspaper, the New York World. Over the next few years she pioneered the idea of investigative journalism by writing articles about poverty, housing and labour conditions in New York. This often involved undercover work and she feigned insanity to get into New York's insane asylum on Blackwell's Island.

Bly later wrote in Ten Days in a Mad House (1888): "Excepting the first two days after I entered the asylum, there was no salt for the food. The hungry and even famishing women made an attempt to eat the horrible messes. Mustard and vinegar were put on meat and in soup to give it a taste, but it only helped to make it worse. Even that was all consumed after two days, and the patients had to try to choke down fresh fish, just boiled in water, without salt, pepper or butter; mutton, beef, and potatoes without the faintest seasoning. The most insane refused to swallow the food and were threatened with punishment. In our short walks we passed the kitchen where food was prepared for the nurses and doctors. There we got glimpses of melons and grapes and all kinds of fruits, beautiful white bread and nice meats, and the hungry feeling would be increased tenfold. I spoke to some of the physicians, but it had no effect, and when I was taken away the food was yet unsalted."

Bly discovered while staying in the hospital that patients were fed vermin-infested food and physically abused by the staff. She also found out that some patients were not psychologically disturbed but were suffering from a physical illness. Others had been maliciously placed there by family members. For example, one woman had been declared insane by her husband after he caught her being unfaithful. Bly's scathing attacks on the way patients were treated at Blackwell's Island led to much needed reforms.

After reading Jules Verne's Around the World in Eighty Days in 1889, Bly suggested to Joseph Pulitzer that his newspaper should finance an attempt to break the record illustrated in the book. He liked the idea and used Bly's journey to publicize the New York World. The newspaper held a competition which involved guessing the time it would take Bly to circle the globe. Over 1,000,000 people entered the contest and when she arrived back in New York on 25th January, 1890, she was met by a massive crowd to see her break the record in 72 days, 6 hours, 11 minutes and 14 seconds.

Bly retired from journalism after marrying Robert Seaman in 1895. Seaman, the millionaire owner of the Iron Clad Manufacturing Company and the American Steel Barrel Company, died in 1904. Bly decided to take over the running of these two ailing companies. Recognizing the importance of the well-being of the workers, Bly introduced a series of reforms that included the provision of health-care schemes, gymnasiums and libraries.

Bly was on holiday in Europe on the outbreak of the First World War. She immediately travelled to the Eastern Front where she reported the war for the New York Journal American.

Nellie Bly died of pneumonia at St. Mark's Hospital in New York City on 27th January, 1922. She was interred at Woodlawn Cemetery in the Bronx.

Primary Sources

(1) Nellie Bly, Ten Days in a Mad House (1888)

As the wagon was rapidly driven through the beautiful lawns up to the asylum, my feelings of satisfaction at having attained the object of my work were greatly dampened by the look of distress on the faces of my companions. Poor women, they had no hopes of a speedy delivery. They were being driven to a prison, through no fault of their own, in all probability for life. In comparison, how much easier it would be to walk to the gallows than to this tomb of living horrors! On the wagon sped, and I, as well as my comrades, gave a despairing farewell glance at freedom as we came in sight of the long stone buildings.

(2) Nellie Bly, Ten Days in a Mad House (1888)

We were sent to the bathroom, where there were two coarse towels. I watched crazy patients who had the most dangerous eruptions all over their faces dry on the towels and then saw the women with clean skin turn to use them. I went to the bathtub and washed my face at the running faucet and my underskirt did duty as a towel.

Before I had completed my ablutions a bench was brought into the bathroom. Miss Grupe and Miss McCarten came in with combs in their hands. We were told to sit down on the bench and the hair of forty-five women was combed with one patient, two nurses, and six combs. As I saw some of the sore heads combed I thought this was another dose I had not bargained for.

(3) Nellie Bly, Ten Days in a Mad House (1888)

The eating was one of the most horrible things. Excepting the first two days after I entered the asylum, there was no salt for the food. The hungry and even famishing women made an attempt to eat the horrible messes. Mustard and vinegar were put on meat and in soup to give it a taste, but it only helped to make it worse. Even that was all consumed after two days, and the patients had to try to choke down fresh fish, just boiled in water, without salt, pepper or butter; mutton, beef, and potatoes without the faintest seasoning. The most insane refused to swallow the food and were threatened with punishment. In our short walks we passed the kitchen where food was prepared for the nurses and doctors. There we got glimpses of melons and grapes and all kinds of fruits, beautiful white bread and nice meats, and the hungry feeling would be increased tenfold. I spoke to some of the physicians, but it had no effect, and when I was taken away the food was yet unsalted.

People in the world can never imagine the length of days to those in asylums. They seemed never ending, and we welcomed any event that might give us something to think about as well as talk of. There is nothing to read, and the only bit of talk that never wears out is conjuring up delicate food that they will get as soon as they get out. Anxiously the hour was watched for when the boat arrived to see if there were any new unfortunates to be added to our ranks. When they came and were ushered into the sitting-room the patients would express sympathy to one another for them and were anxious to show them little marks of attention."

(4) Nellie Bly, Ten Days in a Mad House (1888)

I always made a point of telling the doctors I was sane, and asking to be released, but the more I endeavored to assure them of my sanity, the more they doubted it. 'What are you doctors here for?' I asked one, whose name I cannot recall. 'To take care of the patients and test their sanity,' he replied. 'Very well,' I said. 'There are sixteen doctors on this island, and, excepting two, I have never seen them pay any attention to the patients. How can a doctor judge a woman's sanity by merely bidding her good morning and refusing to hear her pleas for release? Even the sick ones know it is useless to say anything, for the answer will be that it is their imagination.' 'Try every test on me,' I have urged others, 'and tell me am I sane or insane? Try my pulse, my heart, my eyes; ask me to stretch out my arm, to work my fingers, as Dr. Field did at Bellevue, and then tell me if I am sane.' They would not heed me, for they thought I raved. The insane asylum on Blackwell's Island is a human rat-trap. It is easy to get in, but once there it is impossible to get out.

(5) Nellie Bly, Six Months in Mexico (1888)

The press of Mexico is like any of the other subjects of that monarchy, yet it is a growing surprise to the American used to free movement, speech and print who visits Mexico with the attained idea that it is a republic. Even our newspapers have been wont to clip from the little sheets which issue from that country, believing them untrammeled, and quoting them as the best authority, when, in truth, they are but tools of the organized ring, are only capable of deceiving the outsider.

In the City of Mexico there are about twenty-five newspapers published, and throughout the empire some few, which are perused by the smallest possible number of people. The Mexicans understand thoroughly how the papers are run, and they consequently have not the slightest respect in the world for them. One can travel for miles, or by the day, and never see a man with a newspaper. They possess such a disgust for newspapers that they will not even use one of them as a subterfuge to hide behind in a street car when some woman with a dozen bundles, three children and two baskets is looking for a seat.

The best paper in Mexico is El Monitor Republicano (the Republican Monitor), which claims to have, in the city, suburbs, and United States, a circulation of five thousand. It is printed entirely in Spanish. The Mexican Financier is a weekly paper – filled with advertisements from the States – which is published in English and Spanish, and is bought only by those who want to learn the Spanish language, yet it is the best English paper in Mexico. Another English paper is published by an American, Howell Hunt, in Zacatecas, but it, like the rest, is of little or no account. One of the newsiest, if not the newsiest, is El Tiempo (the Times), which is squelched about every fortnight, as it is anti-governmental.

(6) Nellie Bly, Six Months in Mexico (1888)

Mexicans are always manana until it comes to bull-fights and love affairs. To know a Mexican in daily life is to witness his courtesy, his politeness, gentleness; and then see him at a bull-fight, and he is hardly recognizable. He is literally transformed. His gentleness and "manana" have disappeared; his eyes flash, his cheeks flush – in fact, he is the picture of "diabolic animation." It is all "hoy" to-day with him. Even the Spanish lady of ease and high heels forgets her mannerisms and appears like some painted heathen jubilant over the roasting of a zealous missionary.

There have been some very good bull-fights lately in the suburbs, for fighting is prohibited within a certain distance of the city. When they say a good bull-fight, it means that the bulls have been ferocious and many horses and men have been killed...

The bull ring resembles somewhat a race course; the highest row is covered and called boxes. They are divided into small squares, which are meant to hold six but are crowded with four. Miserable chairs without backs are the comfortable seats. Below is the amphitheater, arranged exactly like circus seats. Different prices are charged and the cheapest is the sunny side, where all the poor sit. A fence painted in the national colors – red, green and white – of some six feet in height, incloses the ring. Three band-stands, equal distances apart, are filled with brilliantly uniformed musicians.

The judge is appointed by the municipality, but the fighters have a right to refuse to fight under one judge whom they think will compel them to take unnecessary risks with a treacherous bull, for a judge once chosen his commands are law, and no excuse will be accepted for not obeying, but a fine deducted from the fighter's salary, and he loses cast with the audience. The judge is in a box in the center of the shady side; with him is some prominent man, for every fight must be honored with the presence of some "high-toned" individual, while behind stands the bugler, a small boy in gay uniform, with a bugle slung to his side, by which he conveys the judge's whispered commands to the fighters in the ring.

(7) Nellie Bly, Six Months in Mexico (1888)

Very few people outside of the Republic of Mexico have the least conception of how government affairs are run there. The inhabitants of Mexico – at least it is so estimated – number 10,000,000 souls, 8,000,000 being Indians, uneducated and very poor. This large majority has no voice in any matter whatever, so the government is conducted by the smaller, but so-called better class. My residence in Mexico of five months did not give me ample time to see all these things personally, but I have the very best authority for all statements. Men whom I know to be honorable have given me a true statement of facts which have heretofore never reached the public prints. That such things missed the public press will rather astonish Americans who are used to a free press; but the Mexican papers never publish one word against the government or officials, and the people who are at their mercy dare not breathe one word against them, as those in position are more able than the most tyrannical czar to make their life miserable. When this is finished the worst is yet untold by half, so the reader can form some idea about the Government of Mexico.

President Diaz, according to all versions, was a brave and untiring soldier, who fought valiantly for his beautiful country. He was born of humble parents, his father being a horse dealer, or something of that sort; but he was ambitious, and gaining an education entered the field as an attorney-at-law. Although he mastered his profession, all his fame was gained on the battle-field. Perfirio Diaz is undoubtedly a fine-looking man, being what is called a half-breed, a mixture of Indian and Spaniard. He is tall and finely built, with soldierly bearing. His manners are polished, with the pleasing Spanish style, compelling one to think - while in his presence - that he could commit no wrong; the brilliancy of his eyes and hair is intensified by the carmine of cheek and whiteness of brow, which, gossip says, are put there by the hand of art. Diaz has been married twice - first to an Indian woman, if I remember rightly, who left him with one child, and next to a daughter of the present Secretary of the Interior, Manuel Romero Rubio. She is handsome, of the Spanish type, a good many years younger than the president, and finely educated, speaking Spanish, French and English fluently. Mrs. Diaz has no children, but is stepmother to two - a daughter and a son of the president. The president, so far as rumor goes, follows not in the footsteps of his countrymen, has no more loves than one, and is really devoted to Mrs. Diaz.

There are two political parties, a sort of a Liberal and Conservative concern, but if you ask almost any man not in an official position he will hesitate and then explain that there are really two parties; that he has almost forgotten their names, but he has never voted, no use, etc. Juarez, who crushed Maximilian, while a good president in some respects, planted the seeds of dishonesty when he claimed the churches and pocketed the spoils therefrom. Every president since then has done what he could to excel Juarez in this line. When Diaz first took the presidency he had the confidence and respect of the people for his former conduct. They expected great things of him, but praise in a short time was given less and less freely, and the people again realized that their savior had not yet been found. When his term drew near a close, his first bite made him long for more, and he made a contract with Manuel Gonzales to give him the presidency if he would return it at the end of his time, as the laws of Mexico do not permit a president to be his own successor, but after the expiration of another term (four years) he can again fill the position.

The constitution of Mexico is said to excel, in the way of freedom and liberty to its subjects, that of the United States; but it is only on paper. It is a republic only in name, being in reality the worst monarchy in existence. Its subjects know nothing of the delights of a presidential campaign; they are men of a voting age, but they have never indulged in this manly pursuit, which even our women are hankering after. No two candidates are nominated for the position, but the organized ring allows one of its members - whoever has the most power - to say who shall be president; they can vote, though they are not known to do so; they think it saves trouble, time, and expense to say at first, "this is the president," and not go to the trouble of having a whole nation come forward and cast the votes, and keep the people in drunken suspense for forty-eight hours, while the managers miscount the ballots, and then issue bulletins stating that they have put in their man; then the self-appointed president names all the governors, and divides with them the naming of the senators; this is the ballot in Mexico.

(8) Nellie Bly, Around the World in Seventy-Two Days (1890)

What gave me the idea?

It is sometimes difficult to tell exactly what gives birth to an idea. Ideas are the chief stock in trade of newspaper writers and generally they are the scarcest stock in market, but they do come occasionally,

This idea came to me one Sunday. I had spent a greater part of the day and half the night vainly trying to fasten on some idea for a newspaper article. It was my custom to think up ideas on Sunday and lay them before my editor for his approval or disapproval on Monday. But ideas did not come that day and three o'clock in the morning found me weary and with an aching head tossing about in my bed. At last tired and provoked at my slowness in finding a subject, something for the week's work, I thought fretfully:

"I wish I was at the other end of the earth!"

"And why not?" the thought came: "I need a vacation; why not take a trip around the world?"

It is easy to see how one thought followed another. The idea of a trip around the world pleased me and I added: "If I could do it as quickly as Phileas Fogg did, I should go."

Then I wondered if it were possible to do the trip eighty days and afterwards I went easily off to sleep with the determination to know before I saw my bed again if Phileas Fogg's record could be broken.

I went to a steamship company's office that day and made a selection of time tables. Anxiously I sat down and went over them and if I had found the elixir of life I should not have felt better than I did when I conceived a hope that a tour of the world might be made in even less than eighty days.

I approached my editor rather timidly on the subject. I was afraid that he would think the idea too wild and visionary.

"Have you any ideas?" he asked, as I sat down by his desk.

"One," I answered quietly.

He sat toying with his pens, waiting for me to continue, so I blurted out:

"I want to go around the world!"

"Well?" he said, inquiringly looking up with a faint smile in his kind eyes.

"I want to go around in eighty days or less. I think I can beat Phileas Fogg's record. May I try it?"

To my dismay he told me that in the office they had thought of this same idea before and the intention was to send a man. However he offered me the consolation that he would favor my going, and then we went to talk with the business manager about it.

"It is impossible for you to do it," was the terrible verdict. "In the first place you are a woman and would need a protector, and even if it were possible for you to travel alone you would need to carry so much baggage that it would detain you in making rapid changes. Besides you speak nothing but English, so there is no use talking about it; no one but a man can do this."

"Very well," I said angrily, "Start the man, and I'll start the same day for some other newspaper and beat him."

"I believe you would," he said slowly. I would not say that this had any influence on their decision, but I do know that before we parted I was made happy by the promise that if any one was commissioned to make the trip, I should be that one.

(9) Nellie Bly, Around the World in Seventy-Two Days (1890)

On Thursday, November 14, 1889, at 9.40.30 o'clock, I started on my tour around the world.

Those who think that night is the best part of the day and that morning was made for sleep, know how uncomfortable they feel when for some reason they have to get up with - well, with the milkman.

I turned over several times before I decided to quit my bed. I wondered sleepily why a bed feels so much more luxurious, and a stolen nap that threatens the loss of a train is so much more sweet, than those hours of sleep that are free from duty's call. I half promised myself that on my return I would pretend sometime that it was urgent that I should get up so I could taste the pleasure of a stolen nap without actually losing anything by it. I dozed off very sweetly over these thoughts to wake with a start, wondering anxiously if there was still time to catch the ship.

Of course I wanted to go, but I thought lazily that if some of these good people who spend so much time in trying to invent flying machines would only devote a little of the same energy towards promoting a system by which boats and trains would always make their start at noon or afterwards, they would be of greater assistance to suffering humanity.

I endeavored to take some breakfast, but the hour was too early to make food endurable. The last moment at home came. There was a hasty kiss for the dear ones, and a blind rush downstairs trying to overcome the hard lump in my throat that threatened to make me regret the journey that lay before me.

(10) Nellie Bly, Around the World in Seventy-Two Days (1890)

When I reached Calais, I found that I had two hours and more to spend in waiting. The train that I intended to take for Brindisi is a weekly mail train that runs to accommodate the mails and not passengers. It starts originally from London, at eight o'clock Friday evening of each week. The rule is that the persons desiring to travel on it must buy their tickets twenty-four hours in advance of the time of its departure. The mail and passengers are carried across the channel, and the train leaves Calais at 1.30 in the morning.

There are pleasanter places in the world to waste time in than Calais. I walked down along the pier and looked at the light-house, which I am told is one of the most perfect in the world, throwing its light farther away than any other. It is a revolving light, and it throws out long rays that seem so little above our heads that I found myself dodging to avoid being struck. Of course, that was purely imaginary on my part, for the rays are just the opposite to being near the ground, but they spread between the ground and the sky like the laths of an unfinished partition. I wonder if the people of Calais ever saw the moon and stars.

There is a very fine railway station built near the end of the pier. It is of generous size, but seemed, as far as I could judge, at this hour of the night, quite empty. There is a smoothly tiled enclosed promenade on the side of the station facing the pier that I should say would prove quite an attraction and comfort for passengers who were forced to wait in that place.

My escort took me into the restaurant where we found something to eat, which was served by a French waiter who could speak some English and understand more. When it was announced that the boat from England was in we went out and saw the be-bundled and be-baggaged passengers come ashore and go to the train which was waiting alongside. One thousand bags of mail were quickly transferred to the train, and then I bade my escort good-bye, and was shortly speeding away from Calais.

There is but one passenger coach on this train. It is a Pullman Palace sleeping-car with accommodations for twenty-two passengers, but it is the rule never to carry more than twenty-one, one berth being occupied by the guard.

The next morning, having nothing else to occupy my time, I thought that I would see what my traveling companions looked like. I had shared the stateroom at the extreme end of the car with a pretty English girl who had the rosiest cheeks and the greatest wealth of golden brown hair I ever saw. She was going with her father, an invalid, to Egypt, to spend the winter and spring months. She was an early riser, and before I was awake had gotten up and joined her father in the other part of the car.

When I went out so as to give the porter an opportunity to make up my stateroom, I was surprised at the strange appearance of the interior of the car. All the head and foot boards were left in place, giving the impression that the coach was divided into a series of small boxes. Some of the passengers were drinking, some were playing cards, and all were smoking until the air was stifling. I never object to cigar smoke when there is some little ventilation, but when it gets so thick that one feels as if it is molasses instead of air that one is inhaling, then I mildly protest. It was soon this occasion, and I wonder what would be the result in our land of boasted freedom if a Pullman car should be put to such purposes. I concluded it is due to this freedom that we do not suffer from such things. Women travelers in America command as much consideration as men.

(11) Nellie Bly, Around the World in Seventy-Two Days (1890)

My escort after giving some order to the porter went out to see about my ticket, so I took a survey of an English railway compartment. The little square in which I sat looked like a hotel omnibus and was about as comfortable. The two red leather seats in it run across the car, one backing the engine, the other backing the rear of the train. There was a door on either side and one could hardly have told that there was a dingy lamp there to cast a light on the scene had not the odor from it been so loud. I carefully lifted the rug that covered the thing I had fallen over, curious to see what could be so necessary to an English railway carriage as to occupy such a prominent position. I found a harmless object that looked like a bar of iron and had just dropped the rug in place when the door opened and the porter, catching the iron at one end, pulled it out, replacing it with another like it in shape and size.

"Put your feet on the foot warmer and get warm, Miss," he said, and I mechanically did as he advised.

My escort returned soon after, followed by a porter who carried a large basket which he put in our carriage. The guard came afterwards and took our tickets. Pasting a slip of paper on the window, which backwards looked like "etavirP," he went out and locked the door.

"How should we get out if the train ran the track?" I asked, not half liking the idea of being locked in a box like an animal in a freight train.

"Trains never run off the track in England," was the quiet, satisfied answer.

"Too slow for that," I said teasingly, which only provoked a gentle inquiry as to whether I wanted anything to eat.

With a newspaper spread over our laps for a table-cloth, we brought out what the basket contained and put in our time eating and chatting about my journey until the train reached London.

As no train was expected at that hour, Waterloo Station was almost deserted. It was some little time after we stopped before the guard unlocked the door of our compartment and released us. Our few fellow-passengers were just about starting off in shabby cabs when we alighted. Once again we called goodbye and good wishes to each other, and then I found myself in a four-wheeled cab, facing a young Englishman who had come to meet us and who was glibly telling us the latest news.

I don't know at what hour we arrived, but my companions told me that it was daylight. I should not have known it. A gray, misty fog hung like a ghostly pall over the city. I always liked fog, it lends such a soft, beautifying light to things that otherwise in the broad glare of day would be rude and commonplace.

"How are these streets compared with those of New York?" was the first question that broke the silence after our leaving the station.

"They are not bad," I said with a patronizing air, thinking shamefacedly of the dreadful streets of New York, although determined to hear no word against them.

Westminster Abbey and the Houses of Parliament were pointed out to me, and the Thames, across which we drove. I felt that I was taking what might be called a bird's-eye view of London. A great many foreigners have taken views in the same rapid way of America, and afterwards gone home and written books about America, Americans, and Americanisms.