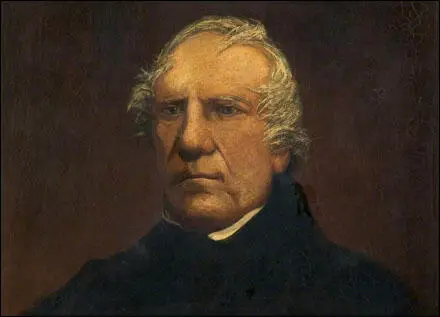

Samuel Bamford

Samuel Bamford, was born on 28th February 1788 in Middleton, near Manchester. Samuel's father, Daniel, was a handloom weaver of muslin, part-time schoolteacher, and a composer of religious songs. Daniel and his wife Hannah, the daughter of a local shoemaker, were both staunch Methodists.

In the early 1790s, Daniel Bamford began reading Tom Paine. After reading The Rights of Man and Age of Reason, Bamford abandoned Methodism and formed a small group of radicals who held regular meetings in Middleton. This created conflict in the town and Bamford and his small group of followers suffered considerable abuse from local people.

In 1794 the Bamford family moved to Manchester where Daniel became the manager of a cotton factory. Soon after arriving in the city, Samuel's mother and his two brothers died of smallpox. Samuel began attending Manchester Grammar Free School but after his father remarried he was sent back to Middleton to live with his uncle.

At the age of fourteen Samuel returned to Manchester and obtained a job sweeping the floor of a local warehouse. This was followed by work as a labourer on a farm near Prestwich. In 1805, now aged seventeen, Samuel walked to South Shields and found employment on a coal ship. Life as a sailor also failed to satisfy Samuel and he returned to Manchester and found menial work in a local warehouse. Samuel Bamford continued to educate himself and during this time he read John Milton, William Shakespeare and Robert Burns. He also became interested in the books of radicals such as Tom Paine and William Cobbett.

Samuel Bamford married in 1812 and soon afterwards he purchased two looms and set himself and his wife up as weavers. Bamford combined this work with writing poetry and selling books. None of these activities were very successful and the Bamfords suffered a considerable amount of poverty.

Bamford became interested in John Cartwright and his campaign for parliamentary reform. In 1816 Bamford formed a Middleton branch of the Hampden Reform Club, an organisation started by Cartwright in 1812. Bamford now became very active in the campaign for universal suffrage and organised several meetings on parliamentary reform in local towns and villages. The authorities heard about Bamford's meetings and in March 1817 he was arrested and charged with treason. He was tried in London but he was acquitted on the grounds of insufficient evidence.

On 16th August 1819, Samuel Bamford arranged for a large number of people from Middleton to attend the meeting at St. Peter's Field. Bamford's account of the Peterloo Massacre became one of the most important sources of evidence for historians of the event. After the massacre several men, including Bamford, were arrested and charged with "assembling with unlawful banners at an unlawful meeting for the purpose of inciting discontent". Henry Hunt was found guilty and was sent to Ilchester Gaol for two years and six months whereas Samuel Bradford, Joseph Johnson and Joseph Healey were each sentenced to one year in Lincoln Prison.

After his release from prison Bamford ceased to be active in the campaign for parliamentary reform. He returned to handloom weaving but competition from local factories ment trade was poor and he attempted to supplement his income with selling poetry. In 1826 Bamford found work as the Manchester correspondent for a London newspaper.

Bamford refused to join the Chartists and in the 1840s he upset local radicals by serving as a special constable at Middleton. He was also critical of his formal political friends in his autobiographical works: Passage in the Life of a Radical (1843) and Early Days (1849).

Samuel Bamford died on 13th April 1872 at Harpurhey, Lancashire.

Primary Sources

(1) In his book Passage in the Life of a Radical Samuel Bamford described the procession from Middleton to Manchester on the 16th August, 1819.

First were selected twelve of the most decent-looking youths, who were placed at the front, each with a branch of laurel held in his hand, as a token of peace; then the colours: a blue one of silk, with inscriptions in golden letters, 'Unity and Strength', 'Liberty and Fraternity'; a green one of silk, with golden letters, 'Parliaments Annual', 'Suffrage Universal'.

Every hundred men had a leader, who was distinguished by a spring of laurel in his hat, and the whole were to obey the directions of the principal conductor, who took his place at the head of the column, with a bugleman to sound his orders. At the sound of the bugle not less than three thousand men formed a hollow square, with probably as many people around them, and I reminded them that they were going to attend the most important meeting that had ever been held for Parliamentary Reform. I also said that, in conformity with a rule of the committee, no sticks, nor weapons of any description, would be allowed to be carried. Only the oldest and most infirm amongst us were allowed to carry their walking staves.

Our whole column, with the Rochdale people, would probably consist of six thousand men. At our head were a hundred or two of women, mostly young wives, and mine own was amongst them. A hundred of our handsomest girls, sweethearts to the lads who were with us, danced to the music. Thus accompanied by our friends and our dearest we went slowly towards Manchester.

(2) In his book Passage in the Life of a Radical Samuel Bamford described the attack on the crowd at St. Peter's Fields on the 16th August, 1819.

Mr. Hunt, stepping towards the front of the stage, took off his white hat, and addressed the people. Whilst he was doing so I heard a noise outside the crowd. Some persons said it was the Blackburn people coming, and I stood on tip-toe and looked in the direction whence the noise was coming from, I saw a party of cavalry in blue and white uniform come trotting, sword in hand.

The cavalry received a shout of good-will. The cavalry, waving their sabres over their heads; and then, slackening rein, and striking spur into their seeds, they dashed forward and began cutting the people. "Stand fast," I said, "they are riding upon us;" The cavalry were in confusion; they evidently could not, with the weight of man and horse, penetrate that compact mass of human beings; and their sabres were plied to cut a way through naked held-up hands and defenceless heads. "Shame!" was shouted then "break! break!" they are killing them in front, and they cannot get away." On the breaking of the crowd the yeomanry wheeled, and, dashing whenever there was an opening, they followed, pressing and wounding. Women and tender youths were indiscriminately sabred or trampled.

A number of our people were driven to some timber which lay at the foot of the wall of the Quakers' meeting house. Being pressed by the yeomanry, a number sprung over the balks and defended themselves with stones which they found there. It was not without difficulty, and after several were wounded, they were driven out. A young married woman of our party, with her face all bloody, her hair streaming about her, her bonnet hanging by the string, and her apron weighed with stones, kept her assailant at bay until she fell backwards and was near being taken; but she got away covered with severe bruises.

In ten minutes from the commencement of the havoc the field was an open and almost deserted space. The hustings remained, with a few broken and hewed flag-staves erect, and a torn and gashed banner or two dropping; whilst over the whole field were strewed caps, bonnets, hats, shawls, and shoes, and other parts of male and female dress, trampled, torn, and bloody. Several mounds of human flesh still remained where they had fallen, crushed down and smothered. Some of these still groaning, others with staring eyes, were gasping for breath, and others would never breathe again.

Student Activities

1832 Reform Act and the House of Lords (Answer Commentary)

The Chartists (Answer Commentary)

Women and the Chartist Movement (Answer Commentary)

Benjamin Disraeli and the 1867 Reform Act (Answer Commentary)

William Gladstone and the 1884 Reform Act (Answer Commentary)

Richard Arkwright and the Factory System (Answer Commentary)

Robert Owen and New Lanark (Answer Commentary)

James Watt and Steam Power (Answer Commentary)

Road Transport and the Industrial Revolution (Answer Commentary)

Canal Mania (Answer Commentary)

Early Development of the Railways (Answer Commentary)

The Domestic System (Answer Commentary)

The Luddites: 1775-1825 (Answer Commentary)

The Plight of the Handloom Weavers (Answer Commentary)

Health Problems in Industrial Towns (Answer Commentary)

Public Health Reform in the 19th century (Answer Commentary)

Walter Tull: Britain's First Black Officer (Answer Commentary)

Football and the First World War (Answer Commentary)

Football on the Western Front (Answer Commentary)

Käthe Kollwitz: German Artist in the First World War (Answer Commentary)

American Artists and the First World War (Answer Commentary)