On this day on 30th December

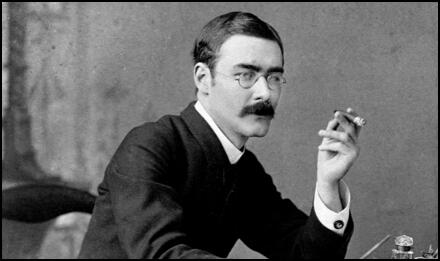

On this day in 1865 Rudyard Kipling, the son of John Lockwood Kipling, principal of the School of Art in Lahore, was born in Bombay on 30th December, 1865. His father sent him to England to be educated at the United Services College, but returned to India in 1882 where he found work as a journalist on the Civil and Military Gazette. Articles and poems that first appeared in the newspaper were later collected and published as Departmental Ditties (1886), Plain Tales from the Hills (1888), Soldiers Three (1890) and Wee Willie Winkie (1890).

Extremely popular in India, Kipling decided to see if he could achieve the same success in England. His first novel published in England, The Light That Failed (1890) did badly but Barrack-Room Ballads (1892) and Jungle Book (1894) established Kipling's reputation. However, some people in Britain found his poetry distasteful and Kipling was accused of jingoism by those hostile to imperialism.

On the outbreak of the Boer War, Kipling travelled to South Africa where he worked with the wounded and produced a newspaper for the troops. By the time he returned to his home in Rottingdean, a small coastal village near Brighton, Kipling was being described as the Laureate of the Empire. His friend Cecil Rhodes described him as having "done more than any other since Disraeli to show the world that the British race is sound at core and that rust and dry rot are strangers to it.".

In 1901 Kipling published the best-selling novel, Kim. Kipling was now extremely famous and to obtain some privacy, Kipling moved to Bateman's, a large house in Burwash. Over the next few years Kipling concentrated on writing children's books such as Just So Stories (1902), Puck of Pook's Hill (1906) and Rewards and Fairies (1910).

Kipling was highly critical of the Liberal Government that had been established by Henry Campbell-Bannerman following the 1906 General Election. Kipling was hostile to its imperial and Ulster policies and the pacifism of many of its leading figures. He was also an active supporter of the National Defence League, an organisation that advocated an increase in military spending and the introduction of a national military service scheme. Some pacifists and socialists accused Kipling and his supporters of mirroring German Junkerism, a belief in a hierarchical society with a military caste at the top.

As a result of his hostility to the Liberal Government, Kipling was not one of those invited by Charles Masterman, the head of the secret War Propaganda Bureau, to the meeting of Britain's leading writers, on 2nd September, 1914. However, after the resignations of the anti-war members of the Cabinet, John Burns, Charles Trevelyan and John Morley, and the dramatic change in the views of David Lloyd George, Kipling was willing to work with Asquith's government.

In later 1914 the War Propaganda Bureau arranged for Kipling to tour of Britain's army camps. The visits resulted in the publication of The New Army (1914). He also visited the Western Front and wrote about his experiences in France at War (1915). Kipling was also commissioned to write a pamphlet on the Royal Navy, The Fringes of the Fleet (1915).

Soon after the outbreak of the First World War, Kipling's only son, John, attempted to enlist in the British Army. After being rejected on health grounds, Kipling used his influence to get his seventeen year old son a commission in the Irish Guards. Six weeks after arriving in France, John Kipling was killed during the Battle of Loos. Kipling never got over losing his son and for many years suffered from depression. This was reflected in the sombre mood of most of his later writing.

Rudyard Kipling, whose autobiography, Something of Myself, was published in 1934, died of a severe hemorrhage in London on 18th January 1936.

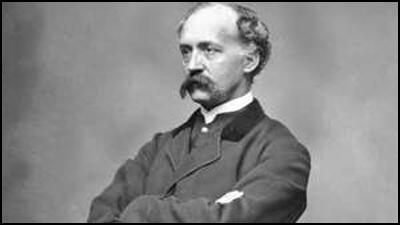

On this day in 1865 anti-slavery campaigner, Henry Winter Davis, died. Henry Winter Davis was born in Annapolis, Maryland on 16th August 1817. After graduating from Kenyon College he studied law at the University of Virginia.

Davis worked as a lawyer in Baltimore, where he became an active member of the Whig Party. In the dispute over slavery Davis refused to support the political factions on either side and in 1860 was elected to the House of Representatives as a member of the Union Party. Although critical of Abraham Lincoln, it was mainly due to Davis that Maryland did not secede from the Union.

On the outbreak of the Civil War Davis joined the Republican Party and in 1863 was re-elected to the House of Representatives. During the war Davis developed strong opinions against slavery and was associated with the Radical Republicans in Congress.

In 1864 Davis joined with Benjamin Wade in sponsoring a bill the that provided for the administration of the affairs of southern states by provisional governors until the end of the war. They also argued that civil government should only be re-established when half of the male white citizens took an oath of loyalty to the Union.

The Wade-Davis Bill was passed on 2nd July, 1864, with only one Republican voting against it. However, Abraham Lincoln refused to sign it. Lincoln defended his decision by telling Zachariah Chandler, one of the bill's supporters, that it was a question of time: "this bill was placed before me a few minutes before Congress adjourns. It is a matter of too much importance to be swallowed in that way." Six days later Lincoln issued a proclamation explaining his views on the bill. He argued that he had rejected it because he did not wish "to be inflexibly committed to any single plan of restoration".

The Radical Republicans were furious with Lincoln's decision. On 5th August, Davis and Benjamin Wade published an attack on Lincoln in the New York Tribune. In what became known as the Wade-Davis Manifesto, the men argued that Lincoln's actions had been taken "at the dictation of his personal ambition" and accused him of "dictatorial usurpation". They added that: "he must realize that our support is of a cause and not of a man."

Henry Winter Davis also opposed Andrew Johnson and his Reconstruction Plan before losing his seat in the House of Representatives in 1865. Henry Winter Davis, who returned to his law practice in Baltimore until his death later that year.

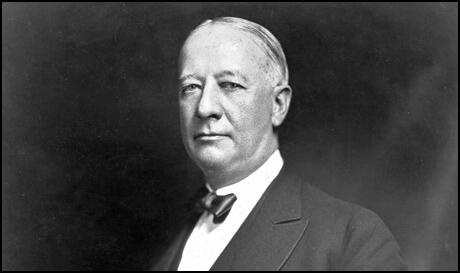

On this day in 1873 progressive politician Alfred (Al) Smith was born in New York City. After a brief formal education he found employment in the Fulton fish market. He become a member of the Democratic Party and in 1903 was elected to the state assembly.

In 1911 he became a member of a commission investigating factory conditions. Shocked by what he found he became associated with those politicians such as Robert Wagner and Frances Perkins, who were attempting to persuade the government to pass legislation to protect industrial workers. A popular politician, he served as speaker of the New York Assembly (1913), sheriff of New York County (1915-17) and president of the Board of Aldermen of New York (1917).

Smith was elected governor of New York for four terms (1919-20, 1923-28). As governor he attempted to bring an end to child labour, improve factory laws, housing and the care of the mentally ill. Smith was a popular figure in the Democratic Party and in 1928 Franklin D. Roosevelt returned to politics in an attempt to help him become president. Smith was the first Roman Catholic to be a serious candidate for the presidency. It is believed that his religion, combined with his opposition to Prohibition, led to his defeat by the Republican candidate, Herbert Hoover.

In 1932 Smith supported his old friend, Franklin D. Roosevelt, in his campaign to become president. However, in the 1936 and 1940 elections, Smith supported the Republican presidential candidates. Alfred Smith died in New York City on 4th October, 1944.

On this day in 1885 cartoonist L. J. Jordaan was born in Amsterdam. Educated at the National Academy for Fine Arts in the Netherlands he specialised in political cartoons and worked for De Ware Jacob (1904-1910), De Nederlandsche Spectator (1907-1908), De Wereld (1911-1913), De Notenkraker (1909-1927).

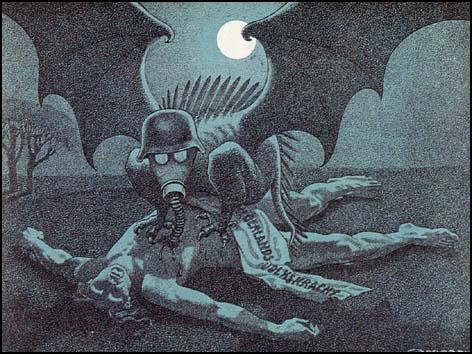

Jordaan moved to De Groene Amsterdammer in 1928. Three years later he became chief cartoonist on the journal. A strong opponent of Adolf Hitler, during the Second World War his anti-Nazi cartoons were published in an underground edition of the journal. Mark Bryant has argued that his cartoon, De Vampyr (1940) is a comment on the Nazi New Order policy: "Jordaan's powerful vampire image has Germany sucking the very lifeblood out of Holland (note the gasmask and bayonet-blade spinal fins)."

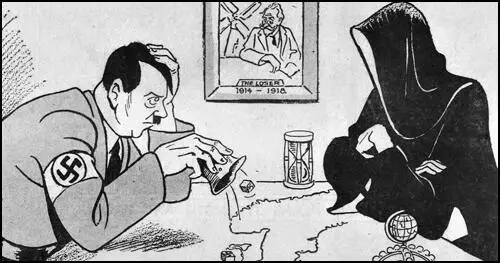

Jordaan's most famous cartoon was De Robot (1940). As the author of the book, World War II in Cartoons (1989): "De Robot, the unstoppable war machine. This fine graphic illustration of the Nazi robot by L. L. Jordaan is all the more remarkable in that it was published in the underground newspaper De Groene Amsterdammer in occupied Holland."

In his later years Jordaan worked for Het Parool and Vrij Nederlan. Jordaan, who also worked as a film critic, retired in 1961. Leendert Jurriaan Jordaan died in Zelhem on 21st April, 1980.

On this day in 1886 Austin Osman Spare, the fourth of the five children of Philip Newton Spare (1857–1928), a policeman, and his wife, Eliza Ann Osman (1860–1939), was born London on the 30th December, 1886. He left his elementary school in Smithfield at 13 but had some formal tuition at the Lambeth School of Art and the Royal College of Art and before exhibiting at the Royal Academy at the age of sixteen. This created some interest in his work and in an interview in The Daily Chronicle he told the reporter that he was interested in inventing his own religion.

Spare became a close friend of Sylvia Pankhurst. He left art college in 1905 without completing the course. The same year, now aged eighteen, published his first book, Earth: Inferno (1905). His first exhibition was at the Bruton Galleries in 1907. It was widely attacked by the critics and George Bernard Shaw suggested that "Spare's medicine is too strong for the average man". His biographer, Phil Baker, claimed that his work was influenced by that of Aubrey Beardsley and Edmund Sullivan: "He took something from both, but he struck an off-key note of the cracked, decayed, and corrupt which was all his own." In 1911 he married the theatre actress Eily Gertrude Shaw (1888–1938).

Spare published The Book of Pleasure in 1913: Robert Ansell has argued: "The years between 1909 and 1913 were Spare’s golden era. He staged several West End exhibitions and enjoyed numerous commissions from private collectors and publishers. The period reached its apex in 1913 with the publication of Spare’s masterpiece, The Book of Pleasure. Inspired by his marriage to the actress Eily Gertrude Shaw in 1911 the book is now regarded as a classic in 20th century esoteric studies. Complex and obscure, Spare’s writing in The Book of Pleasure sketches out a vision of a magical process entirely devoid of ceremony and thus swept away all conventional notions of ritual praxis."

Spare was opposed to the First World War but in 1917 Spare was conscripted into the Royal Army Medical Corps. Early in 1918 the government decided that a senior government figure should take over responsibility for propaganda. On 4th March Lord Beaverbrook, the owner of the Daily Express, was made Minister of Information. Under him was Charles Masterman (Director of Publications) and John Buchan (Director of Intelligence). Lord Northcliffe, the owner of both The Times and the Daily Mail, was put in charge of all propaganda directed at enemy countries. Robert Donald, editor of the Daily Chronicle, was appointed director of propaganda in neutral countries. On the announcement in February 1918, David Lloyd George was accused in the House of Commons of using this new system of getting control over all the leading figures in Fleet Street.

Beaverbrook decided to rapidly expand the number of artists in France. He established with Arnold Bennett a British War Memorial Committee (BWMC). The artist chosen for this programme were given different instructions to those sent previously. Beaverbrook told them that pictures were "no longer considered primarily as a contribution to propaganda, they were now to be thought of chiefly as a record."

Artists sent abroad under the BWMC programme included Spare, John Singer Sargent, Augustus John, John Nash, Henry Lamb, Henry Tonks, Eric Kennington, William Orpen, Paul Nash, C. R. W. Nevinson, Colin Gill, William Roberts, Wyndham Lewis, Stanley Spencer, Philip Wilson Steer, George Clausen, Bernard Meninsky, Charles Pears, Sydney Carline, David Bomberg, Gilbert Ledward and Charles Jagger. Most of his Spare's paintings in France such as Operating in a Regimental Aid Post and First Field Dressing featured the work of the Royal Army Medical Corps.

During the war his relationship with his wife, Eily Gertrude Shaw, came to an end. According to Robert Ansell "it was Spare’s satyr-like sexual reputation that probably ended the marriage: his fourth book, The Focus of Life, published in 1921, delivers a dream-like narrative and voluptuous pencil nudes – none of which were his wife. It was well received, but Spare found himself out-of-step and alienated from London’s art society and he retreated to his roots in South London."

From October 1922 to July 1924 Spare edited, jointly with Clifford Bax, the quarterly, Golden Hind for the publishers, Chapman and Hall. It collapsed for lack of support, but during its brief career it reproduced impressive figure drawing and lithographs by Spare and others. In 1925 Spare, Alan Odle, John Austen, and Harry Clarke showed together at the St George's Gallery, and in 1930 at the Godfrey Philips Galleries.

According to the author of Austin Osman Spare (2010): "Spare increasingly parted company with fame and fortune during the 1920s, and between the wars he held selling exhibitions in his council flat. He drew intense pastels of Southwark locals from life, art deco pictures of film stars from magazines, and he experimented with anamorphic distortion, which he termed siderealism."

The Times reported that: "A dreamer of dreams and a seer of visions, he (Spare) had that complete other-worldliness so often depicted in romantic fiction and so rarely found in real life. Money meant nothing to him. With his talents as a figure draughtsman he might easily have commanded a four-figure income in portraiture, but he elected to live quietly and humbly, rarely going out, painting what he wished to paint, and selling his works at three or four guineas each. Even in outward aspect he conformed to type - with his untidy shock of hair, small imperial, and a scarf instead of a collar."

The journalist, Hannen Swaffer, claimed that in 1936 Spare sent a self-portrait painting to Adolf Hitler. According to Swaffer, Hitler was so impressed that he invited Spare to go to Germany to paint him. Spare replied: "Only from negations can I wholesomely conceive you. For I know of no courage sufficient to stomach your aspirations and ultimates. If you are superman, let me be for ever animal.”

Spare worked from a small flat in Brixton during the Second World War. In 1941 Spare was seriously injured during a bombing raid. According to one source: "For three years he struggled to regain the use of his arms until finally, in 1946, in a cramped basement in Brixton, he began to make pictures again, surrounded by stray cats. At the time he had no bed and worked in an old army shirt and tattered jacket. Yet he still charged only an average of £5 per picture." Austin Osman Spare died in South Western Hospital, Landor Road, Stockwell, on 15th May, 1956, following appendicitis.

On this day in 1889 Peggy Goodnough was born in Bennington, Kansas. The daughter of Edwy Goodnough and Minnie Goodnough, was brought up on a farm. At the age of sixteen she found work as a typesetter for the Junction City Sentinel in Kansas. Later she became a reporter for the El Paso Herald and the El Paso Times where she covered the American army's attempts to end the cross-border raids into Texas by Pancho Villa and his band of Mexican revolutionaries.

On the outbreak of the First World War Peggy volunteered to report the war from the Western Front but initially the editor rejected the idea because she was a woman. However, he changed his mind and in June 1917 she was sent to visit the US Army training camps in France. Her articles were very popular and some were published in the Chicago Tribune.

In 1917 jealous male reporters complained to the authorities that Peggy was not a properly accredited war correspondent. Peggy was now forced to return to the United States in an attempt to obtain the necessary permission to work on the front-line. The War Department in Washington was strongly opposed to allowing a woman to report the war.

Permission was therefore not granted until 14th October 1918, just a few weeks before the armistice. Peggy now became America's first woman to become officially accredited as a war correspondent. However, Peggy knew that by the time she reached France the war would be over. Determined to see military action, Peggy, now working for the Cleveland Press, decided to visit Siberia to report the role being played by American troops in the Civil War that followed the Russian Revolution. After leaving Russia Peggy moved to China and worked for newspapers in Shanghai and reported on the invasion by Japan for the New York Daily News.

Peggy's first two marriages to George Hull (1910) and John Kinley (1922) ended in divorce. In 1933 she married her third husband, Harvey Deuell. In 1939 Peggy was a founding member of the Overseas Press Club.

Peggy Goodnough had difficulties obtaining permission to report on the Second World War. It was not until the end of 1943 that she was eventually given the necessary papers to cover the Pacific War. Working now for the North American Newspaper Alliance and the Cleveland Plain Dealer, Peggy was confined to military bases and hospitals in Hawaii until January 1945. Even then, she was only allowed to visit islands that were now under the control of the US Army.

Peggy wrote about the problems that women faced while trying to report the war. "I am a woman and as a woman am not permitted to experience the hazards of real war reporting." However, her human interest stories of the war had a tremendous impact on her readers. One soldier wrote to her during the war claiming: "You will never realize what those yarns of yours did to this gang. You made them know they weren't forgotten."

In 1953 Peggy, now a widow, retired to Carmel Valley, California. Peggy Deuell died of breast cancer on 19th June, 1967.

On this day in 1892 Sidney Strube, the son of Frederick Strube, was born in Bishopsgate. After studying at St Martin's School of Art he found work as a draughtsman for a furniture company before joining a small advertising agency.

In 1910 he enrolled at the John Hassall Art School he began producing cartoons. He sold his first work to the Conservative and Unionist magazine in 1909, Soon afterwards he began producing a weekly cartoon for Throne and Country. He also had cartoons published in The Bystander.

On the outbreak of the First World War Strube joined the Artists' Rifles. Instead of being sent abroad he became a PT and bayonet instructor. After leaving the army in 1918 he became the political cartoonist of The Daily Express.

Martin Walker pointed out in his book, Daily Sketches: A Cartoon History of Twentieth Century Britain (1978) that "Strube... created John Citizen, a sharp-eyed alert little fellow who got whiter with the years, but he always wore the same bowler hat, was always patriotic." Strube described his character as someone "with his everyday grumbles and problems, trying to keep his ear to the ground, his nose to the grindstone, his eye to the future and his chin up - all at the same time."

Sidney Strube was a great supporter of the Conservative Party. During the General Strike in 1926, Stanley Baldwin was portrayed as John Bull whereas Ramsay MacDonald, the leader of the Labour Party wore a "foreign-looking striped shirt".

According to Mark Bryant Strube "worked on Whatman board with indian ink after sketching preliminary outlines in pencil." Influenced by the work of Bernard Partridge, Frank Reynolds and David Low, his cartoons were so successful that by 1931 he was being paid £10,000 a year by The Daily Express.

During the Second World War Sidney Strube produced a series of very patriotic cartoons. This included several of Winston Churchill, who was often portrayed as a bull-dog. He also provided drawings for several propaganda posters that were published by the British government.

Strube was sacked in 1948 after an argument with the editor The Daily Express and was replaced by Michael Cummings as the newspaper's chief political cartoonist. He then freelanced for The Sunday Times, Time and Tide and The Tatler. Strube died at his home in Hampstead on 4th March 1956.

On this day in 1901 Evelyn Sharp met Henry Nevinson for the first time at the Prince's Ice Rink in Knightsbridge. She later recalled, "when he took my hand in his and we skated off together as if all our life before had been a preparation for that moment." Although he was married to Margaret Nevinson, they soon became lovers. Nevinson wrote in his diary that Evelyn "was both pretty and wise - exquisite in every way". Evelyn later told him: "The first time I saw you I knew you wanted something you have never got." The situation was further complicated by the fact that Nevinson was also having an affair with Nannie Dryhurst.

Nevinson, who was an experienced journalist, helped her to find work writing articles for the Daily Chronicle and the Manchester Guardian, a newspaper that published her work for over thirty years. Sharp's journalism made her more aware of the problems of working-class women and she joined the Women's Industrial Council and the National Union of Women's Suffrage Societies. Sharp and Nevinson shared the same political beliefs. He told his old friend from university, Philip Webb, that Evelyn possessed "a peculiar humour, unexpected, stringent, keen without poison" but "above all she is a supreme rebel against injustice.

Evelyn Sharp worked as a journalist and a part-time teacher. In November, 1903, her father died: "I went to Brook Green to live for the best part of a year with my mother... By the time I was free again I had lost my teaching connection, and, rather than attempt to work it up again, I determined to rely instead on journalism for my regular income. I was equally sorry to give up my private pupils and my school lecturing, which not only interested me but also brought me into contact with children at a period when I was writing stories about them. At the same time, I have never regretted a change which caused me seriously to adopt a great profession and led to many journeys and adventures that would not otherwise have come my way."

In 1905 Sharp and Nevinson established the Saturday Walking Club. Other members included William Haselden, Henry Hamilton Fyfe, Clarence Rook and Charles Lewis Hind. According to Angela V. John, the author of Evelyn Sharp: Rebel Women (2009): "Although Evelyn and Henry were serious walkers, both the Saturday Walking Club and dining with friends afforded the opportunity to be together in public in a manner that was acceptable."

In May 1906 she told Nevinson that she would give up all her literary fame to "belong to you openly and fairly." The following month she wrote to Nevinson: "If it isn't true that you love me it isn't true that the sun shines or that my heart beats quicker when I hear you at the door. My heart is only ill because you put a smile into it that will never die, and my heart had not learnt to smile before." Evelyn Sharp was desperate to have children, but as Nevinson remained married this was impossible. She told a friend that she knew that she was "longing for the impossible" and that "I can hardly bear to look at a baby now."

In the autumn of 1906 Sharp was sent by the Manchester Guardian to cover a speech by Elizabeth Robins. She later wrote: "Elizabeth Robins, then at the height of her fame both as a novelist and as an actress, sent a stir through the audience when she stepped on the platform. The impression she made was profound, even on an audience predisposed to be hostile; and on me it was disastrous. From that moment I was not to know again for twelve years, if indeed ever again, what it meant to cease from mental strife; and I soon came to see with a horrible clarity why I had always hitherto shunned causes."

As a result of hearing the speech, Sharp joined the the Women's Social and Political Union. Sharp later recalled the differences between the suffragists (NUWSS) and the suffragettes (WSPU). Suffragists had waited and worked for so long that they felt they could wait a little longer. Suffragettes who had become "suddenly aware of an imperative need, could not wait another minute."

Evelyn Sharp made her first WSPU speech at Fulham Town Hall in January 1907. In her autobiography, Unfinished Adventure, Sharp admitted that she was terrified by public speaking and that it caused a "cold feeling at the pit of the stomach". However, she used humour to disarm her audience and Emmeline Pankhurst claimed that she was one of the WSPU's best speakers. She went on a WSPU demonstration with Henry Nevinson on 13th February 1907. He recorded that after being attacked by a police officer he resorted to language that was "something horrible."

In 1907 Sharp began a regular column on women's suffrage for the Daily Chronicle. However, in November the editor decided to stop the articles because they "alienated" so many readers. C. P. Scott, her editor at the Manchester Guardian, disapproved of the WSPU's tactics but admitted that Sharp was "the ablest and best brain in the movement".

In January 1909 Sharp was sent to Denmark to lecture on the militant suffrage movement. The following year she was appointed as secretary for the Kensington branch of the WSPU. Another member was the surgeon Louisa Garrett Anderson and the two women became very close friends. The two women sold Votes for Women in Kensington High Street.

Evelyn Sharp also published Rebel Women (1910), a series of vignettes of suffrage life. Angela V. John, the author of Evelyn Sharp: Rebel Women (2009), has argued: "It brought together in fourteen revealing vignettes the mundane, yet extraordinary, lives of suffragettes. Evelyn tells tales of the unexpected. we see a working-class mother and lady writer making common cause and a little rebel who seizes the moment to join the boys in her own version of cricket. The stories warn us never to jump to conclusions or judge people by appearance."

Evelyn's mother was unhappy about her daughter being a member of the WSPU and made her promise not to do anything that would result in her being sent to prison. In a letter on 25th March 1911, her mother absolved her from that promise: "I am writing to exonerate you from the promise you made me - as regards being arrested - although I hope you will never go to prison, still I feel I cannot any longer be so prejudiced and must really leave it to your own better judgment. So brave, so enthusiastic as you have been for so long - I have really been very unhappy about it and feel I have no right to thwart you - much as I should regret feeling that you were undergoing those terrible hardships which so many noble and brave women have and are doing still... I feel sure what a grief it has been that you could not accompany your friends: I cannot write more but you will be happy now, won't you?"

Evelyn now became active in the militant campaign. On 7th November she was sent to Holloway Prison for fourteen days for breaking government windows. In her autobiography, Unfinished Adventure, she explained what happened when she arrived in prison: "When the doctor asked me if I minded solitary confinement, I surprised him by saying truly that I objected to it because it was not solitary. You might be left alone for twenty-two out of twenty-four hours, but you could never be sure of being left for five minutes without the door being burst suddenly open to admit some official. Yet this threat of interruption, while it destroyed solitude, which I love, never took me from the horror of the locked door, just as one never lost the irritating sense of being peered at through the observation hole."

On 22nd November Evelyn Sharp wrote from her prison cell: "Just by sitting here with cold feet and being given suet pudding (without treacle) for dinner, and going without a bath, and being treated like rather a dangerous child - one is doing more for the cause than all the eloquence of the last five years." However, later Sharp admitted that she felt uncomfortable about taking militant action: "Who am I to be doing all these ugly things when I only long for solitude and a fairy tale to write.... I only know I shall go on till I drop and so will hundreds of others whose names will never be known."

On 5th March 1912, detectives arrived at the WSPU headquarters at Clement's Inn to arrest Christabel Pankhurst, Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence and Frederick Pethick Lawrence. It was the Pethick-Lawrences who edited and financed the WSPU's newspaper, Votes for Women. As Angela V. John has pointed out: "Frederick Pethick Lawrence believed that Evelyn was the one person with the requisite technical experience and political acumen to take over the paper as assistant editor - it was just twenty-four hours away from going to press - and this she agreed to do." Elizabeth Robins has argued that the newspaper now had an editor of "distinguished ability and rare devotion."

Sharp was also an active member of the Women Writers Suffrage League and on 24th August 1913 she was chosen to represent the organisation in a delegation that hoped to meet with the Home Secretary, Reginald McKenna, at the House of Commons to discuss the Cat and Mouse Act. McKenna was unwilling to talk to them and when the women refused to leave the building, Mary Macarthur and Margaret McMillan were physically ejected and Sharp, Sybil Smith and Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence were arrested and sent to Holloway Prison.

The arrest of Sybil Smith, the daughter of the William Randal McDonnell, 6th Earl of Antrim, and the mother of seven children, created problems for the government and Sharp and the other suffragettes were released unconditionally after four days. Henry Nevinson arrived at the prison gates with red roses and a bottle of Muscat. He wrote in his diary that they "had perfect happiness again". Weighing less than seven stone she was taken to the home of Hertha Ayrton where she was looked after by her doctor friend, Louisa Garrett Anderson. A few days later she spent time in the Oxfordshire home of Gerald Gould and Barbara Ayrton Gould.

Evelyn Sharp continued to be involved with Henry Nevinson. As he was a foreign correspondent he was often out of the country. When he was away she wrote him passionate love letters. On one occasion she said: "Oh I am so glad I love some one who could never make me feel ashamed of what I have given so freely." Women found Henry Nevinson very attractive. Henry Brailsford has argued that "Nevinson was a handsome man, who carried himself with a noble air which earned him the nickname of the Grand Duke. His blend of humanity, compassion, and daring made him a popular figure in his own lifetime." Olive Banks commented: "He obviously admired the courage and determination of the militant leaders. At heart a romantic, his view of women was not without its protective side, and female beauty had a strong appeal to him. On the other hand, his passion for freedom, which inspired so much of his work, gave him sympathy also for women's need for political rights and self-determination."

Angela V. John has argued that: "He was cultured and courteous yet rebellious. He travelled to faraway and dangerous places. A touch of shyness, an ability to listen to others and an appreciation of women's rights and of intelligent women ensured that many found him irresistible." Evelyn Sharp also made a big impression on Nevinson. In 1913 he wrote to Sidney Webb: "She (Sharp) has one of the most beautiful minds I know - always going full gallop, as you see from her eyes, but very often in regions beyond the moon, when it takes a few seconds to return. At times she is the very best speaker among the suffragettes."

Sharp left the Women's Social and Political Union in protest against the expulsion by Emmeline Pankhurst of Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence and Frederick Pethick Lawrence. The breakaway group formed the United Suffragists and Sharp edited its journal, Votes for Women. Other members of this organisation included Henry Nevinson, Margaret Nevinson, Hertha Ayrton, Israel Zangwill, Edith Zangwill, Lena Ashwell, Louisa Garrett Anderson, Eveline Haverfield, Maud Arncliffe Sennett, John Scurr, Julia Scurr and Laurence Housman.

Unlike many members of the women's movement, Sharp was unwilling to end the campaign for the vote during the First World War. This brought her criticism from the leaders of the WSPU. In 1914 Emmeline Pankhurst announced that all militants had to "fight for their country as they fought for the vote." In

October 1915, the WSPU changed its newspaper's name from The Suffragette to Britannia. Emmeline's patriotic view of the war was reflected in the paper's new slogan: "For King, For Country, for Freedom'. In the newspaper anti-war activists such as Ramsay MacDonald were attacked as being "more German than the Germans".

Her friend and fellow campaigner for women's suffrage, Beatrice Harraden, objected to the unpatriotic tone of some of her articles in Votes for Women. Evelyn was also asked by C. P. Scott, the editor of the Manchester Guardian, to modify the pacifist tone of some of her stories that were published in the newspaper during the war.

During the First World War a group of wealthy suffragettes, including Janie Allan, decided to fund the Women's Hospital Corps. Evelyn Sharp did support this venture and she visited Louisa Garrett Anderson and Flora Murray when they were running the hospital in Claridge Hotel in Paris.

A pacifist, Sharp was active in the Women's International League for Peace that was established soon after the war started. She was one of 156 British women invited to its conference in The Hague in April 1915. Reginald McKenna, the Home Secretary, refused permission for the women to go. Only Chrystal Macmillan, Kathleen Courtney and Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence, who had already left the country, managed to attend the conference.

Sharp was also a member of the Tax Resistance League and refused to pay income tax on her earnings. She argued that to do so amounted to "taxation without representation". By 1917 she owed six years' tax and the authorities declared her bankrupt. Her possessions were seized and sold at public auction. Her friends came to her aid and purchased items that they later gave back to her.

On 10th January 1918, a majority in the House of Lords, voted for the Qualification of Women Act. Evelyn Sharp wrote that later that night she walked around the scenes of their long fought battle. It "was almost the happiest moment of my life" when "I walked away up Whitehall on the evening that the lost cause triumphed." Two days later Henry Nevinson hosted a dinner in honour of the victory. Guests included Sharp, Elizabeth Robins, J. A. Hobson, Gerald Gould and Barbara Ayrton Gould.

Nevinson later argued that the persistence of the United Suffragists that had made the triumph of 1918 possible. He added that all its members would admit that our very existence through those four years from February 1914 to February 1918, were almost entirely due to the brilliant mind and dogged resolution of Evelyn Sharp, who inspired our members to maintain their enthusiasm."

After the Armistice, Evelyn Sharp, now a member of the Labour Party, worked as a journalist for a variety of newspapers, including the Daily Herald and the Manchester Guardian. She visited Russia several times. In November, 1917, she had written in her diary that she was "thrilled at the news of the Russian Revolution". In an article published in The Nation in 1919, Sharp argued that the Bolsheviks were creating a society "in which no one shall starve, and no able-bodied person shall be idle". She added that communism was "the most magnificent ideal of life ever conceived." However, Sharp never joined the Communist Party of Great Britain and by the early 1920s she had become totally disillusioned by the repressive measures of the Soviet government.

In May 1922 the Manchester Guardian started a daily Women's Page. Edited by Madeline Linford, it dealt with "subjects which are special to women" and aimed at the "intelligent woman". Evelyn Sharp was its first regular columnist. Other contributors included Vera Brittain and Winifred Holtby. As Angela V. John has pointed out: "It became renowned, provoking debates about the necessity for space dedicated to women."

Henry Nevinson and Margaret Nevinson still lived together. They used to eat separately except for Sundays. According to her biographer, Angela V. John: "Her final years were lonely ones, plagued by depression." Christopher Nevinson described their home "a cheerless uninhabited house". Henry wrote: "Children are a quiverful of arrows that pierce the parents' hearts."

In 1928 Margaret told friends that she wanted to go into a nursing home "and have done with it". She tried to drown herself in the bath. Henry Nevinson wrote to Elizabeth Robins about her health: "At present I am in great tribulation, for Mrs. Nevinson's mind is rapidly failing, and I am perplexed what is best for her. To send her to a mental home among strangers seems to me cruel, but all are urging it, partly in hopes of reducing the great expense. I am so much opposed to it that I should far rather go on spending my small savings in the hope that she may end quietly here." Margaret Nevinson died of kidney failure at her Hampstead home, 4 Downside Crescent, on 8th June 1932.

Henry Nevinson married Evelyn Sharpon 18th January 1933 at Hampstead Registry Office. Evelyn was 63 and Henry was in his seventy-seventh year. Evelyn wrote that "if age and experience have any value at all, they should help and not hinder the explorer who sets out to sail the uncharted seas of married life." The prime minister, Ramsay MacDonald, offered to be best man but they refused as they had not approved of him becoming the leader of the National Government. Evelyn shocked the guests by wearing a black dress for the ceremony. Sharp's autobiography, Unfinished Adventure, was published later that year.

Soon after the outbreak of the Second World War the Nevinsons' house in Hampstead was bombed and in October 1940 the couple moved to the vicarage at Chipping Campden, Gloucestershire. Henry Nevinson died aged 85 on 9th November, 1941. Sharp wrote in her diary: "There was a flaming red sunset right across the sky and the reflection of it was across the room."

Margaret Storm Jameson told Evelyn that "you were woven into his life by memories, going back years and years" and that he had depended on her "as an anchor and centre". Maude Royden claimed that Evelyn and Henry's "happiness had lit up a room like a lamp". George Peabody Gooch added that the "greatest thing in his life was their love for each other".

Evelyn returned to living alone in London flats as she had done for most of her adult life. She died in Methuen Nursing Home, 13 Gunnersbury Avenue, Ealing, on 17 June 1955. During her life she had published over thirty books including fifteen novels, several volumes of short stories, the libretto for an opera by Ralph Vaughan Williams, a history of folk dancing and a life of the physicist Hertha Ayrton.

On this day in 1906 social reformer Josephine Butler died. Josephine, the daughter of John Grey and Hannah Annett, was born on 13th April 1828. Grey was a wealthy landowner and the cousin of Earl Grey, the British Prime Minister who led the Whig administration between 1830 and 1834. Her father was a strong advocate of social reform and played a significant role in the campaign for the 1832 Reform Act and the repeal of the Corn Laws. Josephine grew up to share her father's religious and moral principles and his strong dislike of inequality and injustice.

Josephine was an attractive woman and Prince Leopold claimed that she was "considered by many people to be the most beautiful woman in the world." In 1852 Josephine married George Butler, an examiner of schools in Oxford. In the first five years of marriage Josephine had four children. In 1857 the couple moved from Oxford after George Butler was appointed vice-principal of Cheltenham College. George and Josephine had similar political views and during the American Civil War they encountered a great deal of hostility in Cheltenham when they expressed their support for the anti-slavery movement.

In 1863, Eva, Josephine's only daughter, fell to her death in front of her. Josephine was devastated by the death of her six year-old daughter and was never to fully recover from this family tragedy. In an attempt to cope with her grief, Josephine Butler became involved in charity work. This involved Josephine visiting the local workhouse and rescuing young prostitutes from the streets.

Josephine also began to take a keen interest in women's education. In 1867 she joined Anne Jemima Clough in establishing courses of advanced study for women. Later that year Josephine Butler was appointed president of the North of England Council for the Higher Education of Women. The following year Josephine became involved in the campaign to persuade Cambridge University to provide more opportunities for women students. This campaign resulted in the provision of lectures for women and later the establishment of Newnham College.

In 1868 Josephine Butler published her book The Education and Employment of Women. In her pamphlet, she argued for improved educational and employment opportunities for single women. The following year she wrote Women's Work and Women's Culture, in which she argued that women should not "try to rival men since they had a different part to play in society". These views upset some feminists such as Emily Davies who wanted women to compete on the same terms as men. Butler believed that women should have the vote because they were different from men. She argued that women's special role was to protect and care for the weak and that women's suffrage was of vital importance to the morality and welfare of the nation.

In 1869 Josephine Butler began her campaign against the Contagious Diseases Act. These acts had been introduced in the 1860s in an attempt to reduce venereal disease in the armed forces. Butler objected in principal to laws that only applied to women. Under the terms of these acts, the police could arrest women they believed were prostitutes and could then insist that they had a medical examination. Butler had considerable sympathy for the plight of prostitutes who she believed had been forced into this work by low earnings and unemployment.

Josephine Butler toured the country making speeches criticizing the Contagious Diseases Acts. Butler, who was an outstanding orator, attracted large audiences to hear her explain why these laws needed to be repealed. Many people were shocked by the idea of a woman speaking in public about sexual matters. George Butler, who was now principal of Liverpool College, was severely criticised for allowing his wife to become involved in this campaign. Butler continued to support his wife in her work despite the warnings that it would damage his academic career.

Butler also became involved in the campaign against child prostitution. In 1885 Butler joined together with Florence Booth of the Salvation Army and W. T. Stead, the editor of the Pall Mall Gazette, to expose what had become known as the white slave traffic. The group used the case of Eliza Armstrong, a thirteen year-old daughter of a chimney-sweep, who was bought for £5 by a woman working for a London brothel. As a result of the publicity that the Armstrong case generated, Parliament passed the Criminal Law Amendment Act that raised the age of consent from thirteen to sixteen.

After the repeal of the Contagious Diseases Act in 1886, Josephine spent her time nursing her sick husband. After his death in 1890, Josephine wrote Recollections of George Butler (1892) and Personal Reminiscences of a Great Crusade (1896). In her last few years of her life, Josephine became a supporter of the National Union of Suffrage Societies. However, now in her seventies, Josephine was too old to take a prominent role in the movement's activities.

On this day in 1913 Sophia Duleep Singh is taken to court over her refusal to pay taxes. In October 1909 the Women's Freedom League (WFL) established the Women's Tax Resistance League (WTRL). Dora Montefiore was the first person who refused to pay her taxes until women were granted the vote. Outside her home she placed a banner that read: “Women should vote for the laws they obey and the taxes they pay.” As she explained: "I was doing this because the mass of non-qualified women could not demonstrate in the same way, and I was to that extent their spokeswoman. It was the crude fact of women’s political disability that had to be forced on an ignorant and indifferent public, and it was not for any particular Bill or Measure or restriction that I was putting myself to this loss and inconvenience by refusing year after year to pay income tax, until forced to do so by the powers behind the Law."

The first member to take part in the campaign was Dr. Octavia Lewin. It was reported in The Daily Chronicle that the "First Passive' Resister", was was to be taken to court. It was announced in the same report that "the Women's Freedom League intends to organise a big passive resistance movement as a weapon in the fight for the franchise."

Sophia Duleep Singh was one of the first women to sign up as someone willing to be a tax resister. She knew that this was a dangerous move. The courts warned the women that if they refused to pay, they risked the enforced seizure and sale of their property and the worst offenders would be sent to prison.

In May 1911, at Spelthorne petty sessions, Sophia Duleep Singh's refusal to pay licences for her five dogs, carriage, and manservant led to a fine of £3. In July 1911, against arrears of 6s. in rates, she had a seven stone diamond ring impounded and auctioned at Ashford for £10. The ring was bought by a member of the Women's Tax Resistance League and returned to her.

In December 1913 she was summoned again to Feltham police court for not paying her taxes. "The Princess Sophia Duleep Singh, residing at Hampton Road, Hampton Court, attended at Feltham Police Court yesterday upon summonses for refusing to pay taxes... She employed a groom without a licence, and also kept two dogs and a carriage without payment of the necessary licence. She came to court wearing the badge and medal of the Tax Resistance League and was accompanied by six other ladies including the secretary of the league, Mrs Kineton Parkes."

In court she made a statement explaining her reasons for not paying her taxes: "I am unable conscientiously to pay money to the state, as I am not allowed to exercise any control over its expenditure, neither am I allowed any voice in the choosing of members of Parliament, whose salaries I have to help to pay. This is very unjustified. When the women of England are enfranchised and the State acknowledges me as a citizen, I shall, of course, pay my share willingly towards its upkeep, if I am not a fit person for the purposes of representation, why should I be a fit person for taxation?"

Sophia Duleep Singh's refusal to pay a fine of £12 10s. resulted in a pearl necklace, comprising 131 pearls, and a gold bangle studded with pearls and diamonds, being seized under distraint and auctioned at Twickenham town hall, both items being bought by members of Women's Tax Resistance League, the necklace fetching £10 and the bangle £7. "Such actions were a means of achieving publicity. Members of the WTRL, by buying articles under distraint, and organizing protest demonstrations and meetings after the auction, generated interest and sympathy in the movement."

On this day in 1915 C. E. Montague wrote to Francis Dodd about rats in the trenches. "The one thing of which no description given in England any true measure is the universal, ubiquitous muckiness of the whole front. One could hardly have imagined anybody as muddy as everybody is. The rats are pretty well unimaginable too, and, wherever you are, if you have any grub about you that they like, they eat straight through your clothes or haversack to get at it as soon as you are asleep. I had some crumbs of army biscuit in a little calico bag in a greatcoat pocket, and when I awoke they had eaten a big hole through the coat from outside and pulled the bag through it, as if they thought the bag would be useful to carry away the stuff in. But they don't actually try to eat live humans."

Many men killed in the trenches were buried almost where they fell. If a trench subsided, or new trenches or dugouts were needed, large numbers of decomposing bodies would be found just below the surface. These corpses, as well as the food scraps that littered the trenches, attracted rats. One pair of rats can produce 880 offspring in a year and so the trenches were soon swarming with them.

Robert Graves remarked in his book, Goodbye to All That: "Rats came up from the canal, fed on the plentiful corpses, and multiplied exceedingly. While I stayed here with the Welch. a new officer joined the company and, in token of welcome, was given a dug-out containing a spring-bed. When he turned in that night he heard a scuffling, shone his torch on the bed, and found two rats on his blanket tussling for the possession of a severed hand."

George Coppard gave another reason why the rats were so large: "There was no proper system of waste disposal in trench life. Empty tins of all kinds were flung away over the top on both sides of the trench. Millions of tins were thus available for all the rats in France and Belgium in hundreds of miles of trenches. During brief moments of quiet at night, one could hear a continuous rattle of tins moving against each other. The rats were turning them over."

Some of these rats grew extremely large. Harry Patch claimed that "there were rats as big as cats". Another soldier wrote: "The rats were huge. They were so big they would eat a wounded man if he couldn't defend himself." These rats became very bold and would attempt to take food from the pockets of sleeping men. Two or three rats would always be found on a dead body. They usually went for the eyes first and then they burrowed their way right into the corpse.

One soldier described finding a group of dead bodies while on patrol: "I saw some rats running from under the dead men's greatcoats, enormous rats, fat with human flesh. My heart pounded as we edged towards one of the bodies. His helmet had rolled off. The man displayed a grimacing face, stripped of flesh; the skull bare, the eyes devoured and from the yawning mouth leapt a rat.

On this day in 1916 Grigori Rasputin was murdered. That year rumours began to circulate that Rasputin and Alexandra Fedorovna were leaders of a pro-German court group and were seeking a separate peace with the Central Powers. This upset Michael Rodzianko, the President of the Duma, and he told Nicholas II: "I must tell Your Majesty that this cannot continue much longer. No one opens your eyes to the true role which this man (Rasputin) is playing. His presence in Your Majesty's Court undermines confidence in the Supreme Power and may have an evil effect on the fate of the dynasty and turn the hearts of the people from their Emperor."

Mansfield Smith-Cumming, the head of MI6, became very concerned by the influence Rasputin was having on Russia's foreign policy. Samuel Hoare was assigned to the British intelligence mission with the Russian general staff. Soon afterwards he was given the rank of lieutenant-colonel and Mansfield Smith-Cumming appointed him as head of the British Secret Intelligence Service in Petrograd. Other members of the unit included Oswald Rayner, Cudbert Thornhill, John Scale and Stephen Alley. One of their main tasks was to deal with Rasputin who was considered to be "one of the most potent of the baleful Germanophil forces in Russia."

The main fear was that Russia might negotiate a separate peace with Germany, thereby releasing the seventy German divisions tied down on the Eastern Front. One MI6 agent wrote: "German intrigue was becoming more intense daily. Enemy agents were busy whispering of peace and hinting how to get it by creating disorder, rioting, etc. Things looked very black. Romania was collapsing, and Russia herself seemed weakening. The failure in communications, the shortness of foods, the sinister influence which seemed to be clogging the war machine, Rasputin the drunken debaucher influencing Russia's policy, what was to the be the end of it all?"

Samuel Hoare reported in December 1916 that poor leadership and inadequate weaponry had led to Russian war fatigue: "I am confident that Russia will never fight through another winter." In another dispatch to headquarters Hoare suggested that if the Tsar banished Rasputin "the country would be freed from the sinister influence that was striking down to natural leaders and endangering the success of its armies in the field." Giles Milton, the author of Russian Roulette: How British Spies Thwarted Lenin's Global Plot (2013) argues that it was at this point that MI6 made plans to assassinate Rasputin.

At the same time Vladimir Purishkevich, the leader of the monarchists in the Duma, was also attempted to organize the elimination of Rasputin. He wrote to Prince Felix Yusupov: "I'm terribly busy working on a plan to eliminate Rasputin. That is simply essential now, since otherwise everything will be finished... You too must take part in it. Dmitri Pavlovich Romanov knows all about it and is helping. It will take place in the middle of December, when Dmitri comes back... Not a word to anyone about what I've written."

Yusupov replied the following day: "Many thanks for your mad letter. I could not understand half of it, but I can see that you are preparing for some wild action.... My chief objection is that you have decided upon everything without consulting me... I can see by your letter that you are wildly enthusiastic, and ready to climb up walls... Don't you dare do anything without me, or I shall not come at all!"

Eventually, Vladimir Purishkevich and Felix Yusupov agreed to work together to kill Rasputin. Three other men Grand Duke Dmitri Pavlovich Romanov, Dr. Stanislaus de Lazovert and Lieutenant Sergei Mikhailovich Sukhotin, an officer in the Preobrazhensky Regiment, joined the plot. Lazovert was responsible for providing the cyanide for the wine and the cakes. He was also asked to arrange for the disposal of the body.

Yusupov later admitted in Lost Splendor (1953) that on 29th December, 1916, Rasputin was invited to his home: "The bell rang, announcing the arrival of Dmitri Pavlovich Romanov and my other friends. I showed them into the dining room and they stood for a little while, silently examining the spot where Rasputin was to meet his end. I took from the ebony cabinet a box containing the poison and laid it on the table. Dr Lazovert put on rubber gloves and ground the cyanide of potassium crystals to powder. Then, lifting the top of each cake, he sprinkled the inside with a dose of poison, which, according to him, was sufficient to kill several men instantly. There was an impressive silence. We all followed the doctor's movements with emotion. There remained the glasses into which cyanide was to be poured. It was decided to do this at the last moment so that the poison should not evaporate and lose its potency."

Vladimir Purishkevich supported this story in his book, The Murder of Rasputin (1918): "We sat down at the round tea table and Yusupov invited us to drink a glass of tea and to try the cakes before they had been doctored. The quarter of an hour which we spent at the table seemed like an eternity to me.... Yusupov gave Dr Lazovert several pieces of the potassium cyanide and he put on the gloves which Yusupov had procured and began to grate poison into a plate with a knife. Then picking out all the cakes with pink cream (there were only two varieties, pink and chocolate), he lifted off the top halves and put a good quantity of poison in each one, and then replaced the tops to make them look right. When the pink cakes were ready, we placed them on the plates with the brown chocolate ones. Then, we cut up two of the pink ones and, making them look as if they had been bitten into, we put these on different plates around the table."

Lazovert now went out to collect Rasputin in his car on the evening of 29th December, 1916. While the other four men waited at the home of Yusupov. According to Lazovert: "At midnight the associates of the Prince concealed themselves while I entered the car and drove to the home of the monk. He admitted me in person. Rasputin was in a gay mood. We drove rapidly to the home of the Prince and descended to the library, lighted only by a blazing log in the huge chimney-place. A small table was spread with cakes and rare wines - three kinds of the wine were poisoned and so were the cakes. The monk threw himself into a chair, his humour expanding with the warmth of the room. He told of his successes, his plots, of the imminent success of the German arms and that the Kaiser would soon be seen in Petrograd. At a proper moment he was offered the wine and the cakes. He drank the wine and devoured the cakes. Hours slipped by, but there was no sign that the poison had taken effect. The monk was even merrier than before. We were seized with an insane dread that this man was inviolable, that he was superhuman, that he couldn't be killed. It was a frightful sensation. He glared at us with his black, black eyes as though he read our minds and would fool us."

Vladimir Purishkevich later recalled that Felix Yusupov joined them upstairs and exclaimed: "It is impossible. Just imagine, he drank two glasses filled with poison, ate several pink cakes and, as you can see, nothing has happened, absolutely nothing, and that was at least fifteen minutes ago! I cannot think what we can do... He is now sitting gloomily on the divan and the only effect that I can see of the poison is that he is constantly belching and that he dribbles a bit. Gentlemen, what do you advise that I do?" Eventually it was decided that Yusupov should go down and shoot Rasputin.

Yusupov later recalled : "I looked at my victim with dread, as he stood before me, quiet and trusting.... Rasputin stood before me motionless, his head bent and his eyes on the crucifix. I slowly raised the crucifix. I slowly raised the revolver. Where should I aim, at the temple or at the heart? A shudder swept over me; my arm grew rigid, I aimed at his heart and pulled the trigger. Rasputin gave a wild scream and crumpled up on the bearskin. For a moment I was appalled to discover how easy it was to kill a man. A flick of a finger and what had been a living, breathing man only a second before, now lay on the floor like a broken doll."

Stanislaus de Lazovert agrees with this account except that he was uncertain who fired the shot: "With a frightful scream Rasputin whirled and fell, face down, on the floor. The others came bounding over to him and stood over his prostrate, writhing body. We left the room to let him die alone, and to plan for his removal and obliteration. Suddenly we heard a strange and unearthly sound behind the huge door that led into the library. The door was slowly pushed open, and there was Rasputin on his hands and knees, the bloody froth gushing from his mouth, his terrible eyes bulging from their sockets. With an amazing strength he sprang toward the door that led into the gardens, wrenched it open and passed out." Lazovert added that it was Vladimir Purishkevich who fired the next shot: "As he seemed to be disappearing in the darkness, Purishkevich, who had been standing by, reached over and picked up an American-made automatic revolver and fired two shots swiftly into his retreating figure. We heard him fall with a groan, and later when we approached the body he was very still and cold and - dead."

Felix Yusupov added: "Rasputin lay on his back. His features twitched in nervous spasms; his hands were clenched, his eyes closed. A bloodstain was spreading on his silk blouse. A few minutes later all movement ceased. We bent over his body to examine it. The doctor declared that the bullet had struck him in the region of the heart. There was no possibility of doubt: Rasputin was dead. We turned off the light and went up to my room, after locking the basement door."

The Grand Duke Dmitri Pavlovich Romanov drove the men to Varshavsky Rail Terminal where they burned Rasputin's clothes. "It was very late and the grand duke evidently feared that great speed would attract the suspicion of the police." They also collected weights and chains and returned to Yusupov's home. At 4.50 a.m. Romanov drove the men and Rasputin's body to Petrovskii Bridge. that crossed towards Krestovsky Island. According to Vladimir Purishkevich: "We dragged Rasputin's corpse into the grand duke's car." Purishkevich claimed he drove very slowly: "It was very late and the grand duke evidently feared that great speed would attract the suspicion of the police." (37) Stanislaus de Lazovert takes up the story when they arrived at Petrovskii: "We bundled him up in a sheet and carried him to the river's edge. Ice had formed, but we broke it and threw him in. The next day search was made for Rasputin, but no trace was found."

The following day the Tsarina Alexandra Fedorovna wrote to her husband about the disappearance of Grigori Rasputin: "We are sitting here together - can you imagine our feelings - our friend has disappeared. Felix Yusupov pretends he never came to the house and never asked him." The next day she wrote: "No trace yet... the police are continuing the search... I fear that these two wretched boys (Felix Yusupov and Dmitri Romanov) have committed a frightful crime but have not yet lost all hope."

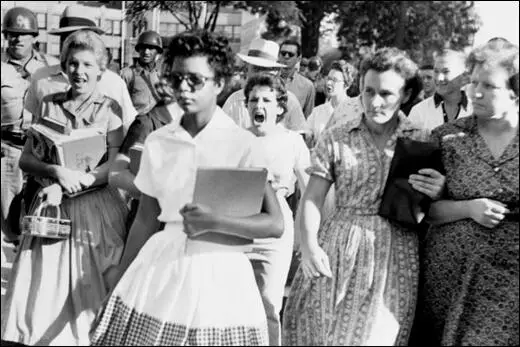

On this day in 1998 the Guardian publish an interview with Elizabeth Eckford about what happened at Little Rock High School in 1957. "I was fifteen in September, 1957. At the time I thought the National Guard were there to protect all students. I thought they were there to see that order was maintained. I didn't realise they were there to keep me out of school. My teachers expected there might be name-calling, but I thought that eventually we would be accepted. I was brought up to believe that students respected adults' orders. That was our expectation, because that was what occurred in the school that we had attended. I had never seen adults appease students who were behaving badly. Many of them did that day, and many of the teachers tried to sit on the fence, tried not to take any side at all. I did not know that Governor Orvel Faubus would side with the segregationists."

"Another day, we tried again. The soldiers told us to get into the car, get our heads down and drove us into the basement by the side entrance of the building. So the mob did not realise we were in. When they did they attacked the black news men who were outside. There were FBI men observing all this and they did nothing to stop it. Then Governor Faubus gave the citizens of Little Rock two choices: keep the schools open and de-segregate or close down all the schools. The vote was to close down the schools and for a full year no school, white or black, operated in Little Rock."

"Of the thousands of students affected, only a few could afford to send their children to families in other cities or boarding schools out of state. I stayed in town and took a correspondence course. Since my parents were accustomed to paying for my books, this was not so difficult. But four of the nine families had to move out, their parents lost their jobs because of pressure on them not to send their children back to school."

"By 1960, the entire state of Arkansas had suffered economically. For years no new industry would come in, and the officials began to change their rhetoric. My definition of a Southern white moderate is someone who reluctantly accepts the law."