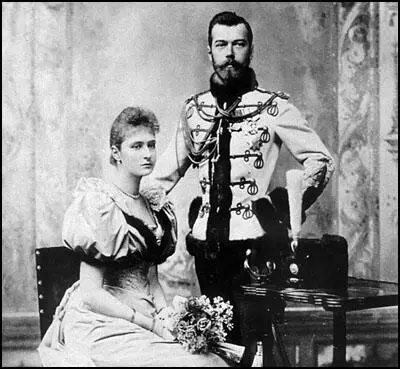

Tsarina Alexandra

Alexandra Fyodorovna, the daughter of Louis IV, the Grand Duke of Hesse-Darmstadt, was born in Germany on 6th June, 1872.

Alexandra, the grand-daughter of Queen Victoria, married Nicholas II, the Tsar of Russia, in October, 1894. Over the next few years she gave birth to four daughters and a son, Alexis.

Alexandra and Nicholas II disliked St. Petersburg. Considering it too modern, they moved the family residence in 1895 from Anichkov Palace to Alexander Palace in Tsarskoe Selo, where they lived in seclusion.

In 1905 Alexandra met Gregory Rasputin, a monk who claimed he had healing powers. Alexis suffered from hemophilia (a disease whereby the blood does not clot if a wound occurs). When Alexis was taken seriously ill in 1908, Rasputin was called to the royal palace. He managed to stop the bleeding and from then on he became a member of the royal entourage.

Alexandra was a strong believer in the autocratic power of Tsardom and urged him to resist demands for political reform. This resulted in her becoming an unpopular person in Russia and this intensified during the First World War.

In September, 1915, Nicholas II assumed supreme command of the Russian Army fighting on the Eastern Front. As he spent most of his time at GHQ, Alexandra now took responsibility for domestic policy. Gregory Rasputin served as her adviser and over the next few months she dismissed ministers and their deputies in rapid succession.

Rumours began to circulate that Alexandra and Gregory Rasputin were leaders of a pro-German court group and were seeking a separate peace with the Central Powers in order to help the survival of the autocracy in Russia. Ariadna Tyrkova commented: "Throughout Russia, both at the front and at home, rumour grew ever louder concerning the pernicious influence exercised by the Empress Alexandra Feodorovna, at whose side rose the sinister figure of Gregory Rasputin. This charlatan and hypnotist had wormed himself into the Tsar’s palace and gradually acquired a limitless power over the hysterical Empress, and through her over the Sovereign. Rasputin’s proximity to the Tsar’s family proved fatal to the dynasty, for no political criticism can harm the prestige of Tsars so effectually as the personal weakness, vice, or debasement of the members of a royal house. Rumours were current, up to now unrepudiated, but likewise unconfirmed, that the Germans were influencing Alexandra Feodorovna through the medium of Rasputin and Stürmer. Haughty and unapproachable, she lacked popularity, and was all the more readily suspected of almost anything, even of pro-Germanism, since the crowd is always ready to believe anything that tends to augment their suspicions."

Gregory Rasputin was also suspected of financial corruption and right-wing politicians believed that he was undermining the popularity of the regime. Felix Yusupov, the husband of the Tsar's niece, and Vladimir Purishkevich, a member of the Duma, formed a conspiracy to murder Rasputin. On 29th December, 1916, Rasputin was invited to Yusupov's home where he was given poisoned wine and cakes. When this did not kill him he was shot by Yusupov and Purishkevich and then dropped through a hole in the frozen canal outside the house.

As supreme command of the Russian Army the Tsar was linked him to the country's military failures and during 1917 there was a strong decline in support for Nicholas II in Russia. On 13th July, 1917, the Russian Army High Command recommended that Nicholas abdicated. Two days later the Tsar renounced the throne.

The Tsar and his immediate family were arrested and negotiations began to find a place of overseas exile. P. N. Milyukov persuaded David Lloyd George, to offer the family political asylum in Britain. However, King George V, who feared that the presence of Nicholas would endanger his own throne, forced Lloyd George to withdraw the offer.

Nicholas and his family were moved to the remote Siberian city of Ekaterinburg where he was held captive by a group of Bolsheviks. Alexandra Fyodorovna, her husband and children, were executed on 16th July 1918.

Primary Sources

(1) Alexandra Fyodorovna, letter to Nicholas II (August, 1915)

Our souls are fighting for the right against the evil. You are proving yourself the Autocrat without which Russia cannot exist. God anointed you in your coronation and God, who is always near you, will save your country and throne through your firmness.

(2) Michael Rodzianko, the President of the Duma, later wrote about the role of Grigory Rasputin during the First World War in his book, The Fall of the Empire.

Profiting by the Tsar's arrival at Tsarskoe I asked for an audience and was received by him on March 8th. "I must tell Your Majesty that this cannot continue much longer. No one opens your eyes to the true role which this man (Rasputin) is playing. His presence in Your Majesty's Court undermines confidence in the Supreme Power and may have an evil effect on the fate of the dynasty and turn the hearts of the people from their Emperor". My report did some good. On March 11th an order was issued sending Rasputin to Tobolsk; but a few days later, at the demand of the Empress, the order was cancelled.

(3) Alexander Kerensky, Russia and History's Turning Point (1965)

The Tsarina's blind faith in Rasputin led her to seek his counsel not only in personal matters but also on questions of state policy. General Alekseyev, held in high esteem by Nicholas II, tried to talk to the Tsarina about Rasputin, but only succeeded in making an implacable enemy of her. General Alexseyev told me later about his profound concern on learning that a secret map of military operations had found its way into the Tsarina's hands. But like many others, he was powerless to take any action.

On January 19, Goremykin was replaced by Sturmer, an extreme reactionary who hated the very idea of any form of popular representation or local self-government. Even more important, he was undoubtedly a believer in the need for an immediate cessation of the war with Germany.

During his first few months in office, Sturmer was also Minister of Interior, but the post of Minister of Foreign Affairs was still held by Sazonov, who firmly advocated honouring the alliance with Britain and France and carrying on the war to the bitter end, and who recognized the Cabinet's obligation to pursue a policy in tune with the sentiments of the majority in the Duma.

On August 9, however, Sazonov was suddenly dismissed. His portfolio was taken over by Sturmer, and on September 16, Protopopov was appointed acting Minister of the Interior. The official government of the Russian Empire was now entirely in the hands of the Tsarina and her advisers.

(4) Ariadna Tyrkova, From Liberty to Brest-Litovsk (1918)

Nicholas II remained deaf to these demands, treating them as an insolent infringement of his prerogative as an autocrat. His tenacity augmented the opposition. Throughout Russia, both at the front and at home, rumour grew ever louder concerning the pernicious influence exercised by the Empress Alexandra Feodorovna, at whose side rose the sinister figure of Gregory Rasputin. This charlatan and hypnotist had wormed himself into the Tsar’s palace and gradually acquired a limitless power over the hysterical Empress, and through her over the Sovereign. Rasputin’s proximity to the Tsar’s family proved fatal to the dynasty, for no political criticism can harm the prestige of Tsars so effectually as the personal weakness, vice, or debasement of the members of a royal house. Rumours were current, up to now unrepudiated, but likewise unconfirmed, that the Germans were influencing Alexandra Feodorovna through the medium of Rasputin and Stürmer. Haughty and unapproachable, she lacked popularity, and was all the more readily suspected of almost anything, even of pro-Germanism, since the crowd is always ready to believe anything that tends to augment their suspicions.

(5) Grand Duke Alexander Mikhailovich, letter to Nicholas II (January, 1917)

The unrest grows; even the monarchist principle is beginning to totter; and those who defend the idea that Russia cannot exist without a Tsar lose the ground under their feet, since the facts of disorganization and lawlessness are manifest. A situation like this cannot last long. I repeat once more - it is impossible to rule the country without paying attention to the voice of the people, without meeting their needs, without a willingness to admit that the people themselves understand their own needs.

(6) Alexandra Fyodorovna , letter to Nicholas II (25th February, 1917)

The strikers and rioters in the city are now in a more defiant mood than ever. The disturbances are created by hoodlums. Youngsters and girls are running around shouting they have no bread; they do this just to create some excitement. If the weather were cold they would all probably be staying at home. But the thing will pass and quiet down, providing the Duma behaves. The worst of the speeches are not reported in the papers, but I think that for speaking against the dynasty there should be immediate and severe punishment.

(7) Alexandra Fyodorovna, letter to Nicholas II (26th February, 1917)

The whole trouble comes from these idlers, well-dressed people, wounded soldiers, high-school girls, etc. who are inciting others. Lily spoke to some cab-drivers to find out things. They told her that the students came to them and told them if they appeared in the streets in the morning, they should be shot to death. What corrupt minds! Of course the cabdrivers and the motormen are now on strike. But they say that it is all different from 1905, because they all worship you and only want bread.

(8) General Lukomsky, assistant to the Chief of Staff, letter (2nd March, 1917)

The Tsar entered the hall. After bowing to everybody, he made a short speech. He said that the welfare of his country, the necessity for putting an end to the Revolution and preventing the horrors of civil war, and of directing all the efforts of the State to the continuation of the struggle with the foe at the front, had determined him to abdicate in favour of his brother, the Grand Duke Michael Alexandrovich.

(9) Alexandra Fyodorovna , letter to Nicholas II (14th March, 1917)

I quite understand your action, my hero. I know that you could not have signed anything that was contrary to your oath given at the coronation. We understand each other perfectly without words, and I swear, upon my life, that we shall see you again on the throne, raised there once more by your people, and your army, for the glory of your reign. You saved the empire for your son and the country, as well as your sacred purity, and you shall be crowned by God himself on earth in your own hand.

(10) Official statement issued by the Soviet government in Izvestia (1918)

Lately the approach of the Czechoslovak bands seriously threatened the capital of the Red Urals, Ekaterinburg. In view of this the presidium of the Ural Territorial Soviet decided to shoot Nicholas Romanov, which was done on July 16. The wife and son of Nicholas Romanov were sent to a safe place. The All-Russian Soviet Executive Committee, through its presidium, recognizes as correct the decisions of the Ural Territorial Soviet.