On this day on 16th April

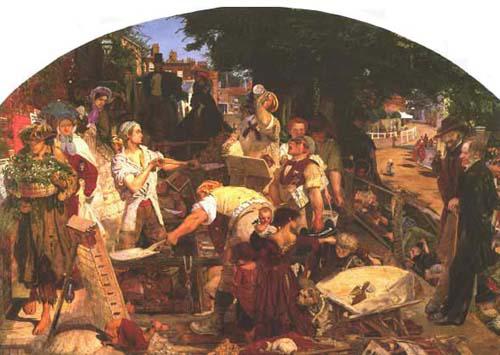

On this day in 1821 Ford Madox Brown was born in Calais. Brown studied art at Bruges, Ghent, Antwerp, Rome and Paris before returning to England in 1845. Three years later Brown became friendly with Dante Gabriel Rossetti and other members of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood.

In 1852 Brown began work on what was to be the first serious attempt by a British artist to represent the working class in an urban environment. The painting shows the excavations for the laying of a sewage system in Hampstead.

The figures in the painting were based on the actual navvies that did the work. Also in the picture are two observers, F. D. Maurice and Thomas Carlyle. Maurice was the leader of the Christian Socialist movement and founder of the Working Men's College, an institution where Brown taught art.

Thomas Carlyle, like Maurice, was another man who Ford Madox Brown greatly admired. Brown had been influenced by Carlyle's view of the "nobleness and even sacredness of work". In the painting Brown attempted to capture what he believed was the "inherent dignity of the British labourer".

Although started in 1852 Work was not completed until 1865. Thomas Plint, a fervent supporter of the Temperance Society from Leeds, purchased the painting before it was finished in 1856. Plint also influenced the content of the picture by suggesting the inclusion of Thomas Carlyle and the women in the picture distributing Temperance tracts.

Another important painting produced by Ford Madox Brown at this time was The Last of England (1852-5). The picture shows the departure of Brown's friend, Thomas Woolner, for the Australian gold-fields.

Brown was also a close associate of William Morris and in 1861 was a founder member of Morris, Marshall, Faulkner & Company. Brown main contribution was designing furniture and stained glass.

Ford Madox Brown completed twelve frescoes for Manchester Town Hall before his death on 6th October 1893.

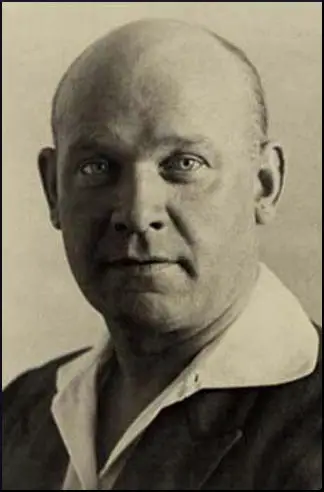

On this day in 1886 Ernst Thälmann was born in Hamburg, Germany. His friend, Wilhelm Pieck, later recalled: "As the son of a class-conscious worker organised in the Social-Democratic Party, Ernst Thälmann came into the Socialist movement in his early youth. He was hardly sixteen years old when he joined the Social-Democratic Party. The indigent circumstances of a proletarian family drove him very early into the drudgery of capitalist exploitation. These circumstances prevented him from following the well-meant advice of his teachers that this talented working-class boy should continue his education."

A member of the Transport Workers Union he joined the Social Democrat Party in 1903. Rose Levine-Meyer knew him during this period: "Ernest Thalmann was a devoted revolutionary, a good orator with a fine instinct for the worker's temper, he was an excellent medium for expounding theories and ideas laid down by others. He was a poor thinker, and not given to abstract study, even lacking enough self-discipline to reach the cultural and theoretical level of an average Party member."

The chairman of the SDP, August Bebel, died following a heart attack on 13th August, 1913. Friedrich Ebert now replaced him as leader of the party. Like most socialists in Germany, Ebert was initially opposed to the idea of Germany going to war. However, once the First World War had started, he ordered the SDP members in the Reichstag to support the war effort.

Karl Liebknecht was the only member of the Reichstag who voted against Germany's participation in the war. He argued: "This war, which none of the peoples involved desired, was not started for the benefit of the German or of any other people. It is an Imperialist war, a war for capitalist domination of the world markets and for the political domination of the important countries in the interest of industrial and financial capitalism. Arising out of the armament race, it is a preventative war provoked by the German and Austrian war parties in the obscurity of semi-absolutism and of secret diplomacy."

Thälmann disagreed with the policies of Friedrich Ebert but he was recruited into the German Army in 1915 and during the First World War fought on the Western Front. He deserted in 1918 and when he arrived back in Germany he joined the Independent Socialist Party (ISP). Other members included Kurt Eisner, Karl Kautsky, Julius Leber, Rudolf Breitscheild and Rudolf Hilferding. Ernst Thälmann was active in the German Revolution in Hamburg that began on 29th October 1918.

Thälmann was on the left-wing of the ISP and was a leading figure in the merger with the German Communist Party (KPD) in November 1920. The following month he was elected to the Central Committee of the KPD. Paul Levi was the leader of the KPD. Other prominent members included Willie Munzenberg, Ernst Toller, Walther Ulbricht, Hermann Duncker, Hugo Eberlein, Paul Frölich, Wilhelm Pieck, Ernest Meyer, Franz Mehring and Clara Zetkin. Levi's moderate approach to communism increased the size of the party.

Ernst Thalmann was elected to the Reichstag. In the summer of 1921 Thälmann went as a representative of the German Communist Party to the 3rd Congress of the Comintern in Moscow and met Lenin. In June 1922 Thälmann survived an assassination attempt at his flat. Over the next few years he established himself as one of the most important figures in the German Communist Party.

Paul Levi remained a supporter of the theories of Rosa Luxemburg and this brought him into conflict with Lenin and Leon Trotsky. They were especially upset with the publication of Our Path: Against Putschism. In 1921 Levi resigned as chairman of the KPD over policy differences. Later that year, Lenin and Trotsky, demanded that he should be expelled from the party.

Ernest Meyer now became the leader of the German Communist Party. Meyer returned to Moscow in 1922 as a member of the German delegation to the 4th World Congress of the Comintern. However, his influence went into decline with the emergence of Thälmann, who replaced Meyer as the Chairman of the KPD in 1925. Ernst Thälmann was the candidate for the German Presidency in 1925. This split the centre-left vote and ensured that the conservative Paul von Hindenburg won the election.

Thälmann, a loyal supporter of Joseph Stalin, willingly put the KPD under the control of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union. In 1928 John Wittorf, an official of the German Communist Party (KPD), and a close friend and protégé of Ernst Thälmann, was discovered to be stealing money from the KPD. Thälmann tried to cover up the embezzlement. When this was discovered by Gerhart Eisler Hugo Eberlein and Arthur Ewert, they arranged for Thälmann to be removed from the leadership. Stalin intervened and had Thälmann reinstated, signaling the removal of people like Eisler and Eberlein and completing the Stalinization of the KPD.

Rose Levine-Meyer commented: "To make him the indisputable leader of the German Communism was to behead the movement and at the same time transform a highly attractive, able personality into a mere puppet." It now became the policy of the KPD to describe members of Social Democratic Party (SDP) as "social fascists" and made it difficult to work together against the emergence of Adolf Hitler.

Thälmann was the party's presidential candidate in 1932. He won 13.2 of the vote compared to the 30.1 received by Adolf Hitler. In January 1933, Thälmann proposed that the German Communist Party (KPD) and the Social Democratic Party (SDP) should organise a general strike in order to remove Hitler. When these negotiations broke down, Thälmann called for the violent overthrow of Hitler's government.

After the Reichstag Fire on 27th February, 1933, the Nazi Party launched a wave of violence against members of the German Communist Party and other left-wing opponents of the regime. This included Thälmann who was arrested and imprisoned on 3rd March 1933. He managed smuggled out details of his treatment: "They ordered me to take off my pants and then two men grabbed me by the back of the neck and placed me across a footstool. A uniformed Gestapo officer with a whip of hippopotamus hide in his hand then beat my buttocks with measured strokes, Driven wild with pain I repeatedly screamed at the top of my voice. Then they held my mouth shut for a while and hit me in the face, and with a whip across chest and back. I then collapsed, rolled on the floor, always keeping face down and no longer replied to any of their questions."

Wilhelm Pieck had managed to escape to the Soviet Union. In July 1936 he issued a statement calling for the release of Thälmann: "If we succeeded in raising a tremendous storm of protest throughout the world, it will be possible to break down the prison walls and as in the case of Dimitrov, deliver Thaelmann from the clutches of the Fascist hangmen. The fact that Ernst Thaelmann has got to spend his fiftieth birthday in the gaols of Hitler-Fascism is an urgent reminder to all the anti-Fascists of the whole world that they must intensify to the utmost their campaign for the release of Thaelmann and the many thousands of imprisoned victims of the White Terror."

Ernst Thälmann spent over eleven years in solitary confinement. He was executed in Buchenwald Concentration Camp on 18th August 1944. A few days later the Nazi government announced that Thälmann and Rudolf Breitscheid had been killed in an Allied bombing attack.

On this day in 1889 Charlie Chaplin was born in London. Both his parents were music hall entertainers and Charlie started appearing on the stage while still a child. His father, Charles Chaplin, deserted the family and eventually died of alcoholism. His mother, Hannah Chaplin, found it increasingly difficult to find work on the stage and in 1895 the family entered the Lambeth Workhouse.

Chaplin later wrote: "Although we were aware of the shame of going to the workhouse, when Mother told us about it both Sydney and I thought it adventurous and a change from living in one stuffy room. But on that doleful day I didn't realize what was happening until we actually entered the workhouse gate. Then the forlorn bewilderment of it struck me; for there we were made to separate, Mother going in one direction to the women's ward and we in another to the children's. How well I remember the poignant sadness of that first visiting day: the shock of seeing Mother enter the visiting-room garbed in workhouse clothes. How forlorn and embarrassed she looked! In one week she had aged and grown thin, but her face lit up when she saw us." Later, Charlie's mother had a mental breakdown and was sent to the Cane Hill Lunatic Asylum. He told a close friend: "I loved my mother almost more when she went out of her mind. She had been so poor and so hungry - I believe it was starving herself for us that affected her brain. She so wanted me to be a successful actor."

When he was sixteen Chaplin won the part of Billy in a West End production of Sherlock Holmes. He later joined Fred Karno's music hall revue. While touring the United States in 1913 Chaplin was discovered by the film producer Mack Sennett. Over the next couple of years Chaplin made a series of short slapstick films for Sennett's Keystone Company. In these films Chaplin developed a character that wore baggy pants, tight frock coat, large shoes on the wrong feet and a black derby hat.

By his thirteenth film, Caught in the Rain (1914), Chaplin began to direct his own films. Chaplin now slowed the pace of his films, reduced the number of visual jokes but increased the time spent on each one. Chaplin placed the emphasis on the character rather than slapstick events. The themes of his films became more serious and reflected his childhood experiences of poverty, hunger and loneliness. Chaplin's work revolutionized film comedy and turned it into an art form.

Chaplin's films were highly successful and became a household name throughout the world. When Chaplin first started with the Keystone Company he was paid $150 a week, by 1915 he was receiving $1,250. Three years later, when he joined First National, Chaplin signed cinema's first million-dollar contract. During this period Chaplin's films included The Tramp (1915), The Pawnshop (1915), Easy Street (1917), The Immigrant (1917) and A Dog's Life (1918).

In 1919 Chaplin joined with D.W. Griffith, Douglas Fairbanks and Mary Pickford to form United Artists, a company that enabled the stars to distribute their films without studio interference. It is also argued that it was in response to a rumour that the film companies intended to put a ceiling on the star salaries. Films produced by Chaplin and his company included The Kid (1921).

Chaplin agreed to be interviewed by Clare Sheridan, a reporter from New York World. She recorded in her diary: "It has been a wonderful evening - I seem to have been talking heart to heart with one who understands, who is full of deep thought and deep feeling. He is full of ideals and has a passion for all that is beautiful. A real artist... And then in spite of his emotional, enthusiastic temperament, with a soundness of judgement... You can see the sadness of the eyes - which the humour of his smile cannot dispel - this man has suffered... He is not Bolshevik nor Communist nor Revolutionary, as I heard rumoured. He is an individualist with the artist's intolerance of stupidity, insincerity, and narrow prejudice." Chaplin advised her against becoming too political: "Don't get lost on the path of propaganda. Live your life as an artist."

Sheridan began a romantic relationship with Chaplin. She later confessed that: "It was not exactly a love affair but a meeting of kindred spirits - we were like two fireflies intoxicated with the same magical feeling for beauty - dancing together by the waves, recognising each other's souls." They were constantly being followed by journalists. One newspaper published the headline: "Charlie Chaplin going to marry British Aristocrat". In one interview concerning age he answered truthfully: "Mrs. Sheridan is four years older than I am." When the article was published it claimed that Chaplin said: "She is old enough to be my mother." Eventually they decided to bring an end to the relationship.

Chaplin made a series of highly successful films including The Gold Rush (1925), The Circus (1928) and City Lights (1931). Chaplin became increasingly concerned with politics. A strong supporter of Franklin D. Roosevelt and the New Deal, Chaplin's film, Modern Times (1936), was seen by some critics as an attack on capitalism. J. Edgar Hoover, head of the Federal Bureau of Investigations (FBI), began compiling a file on Chaplin's activities, including his friendship with radicals such as Upton Sinclair, H. G. Wells, Hanns Eisner, Albert Einstein, Clare Sheridan and Harold Laski.

A strong opponent of racism, in 1937 Chaplin decided to make a film on the dangers of fascism. As Chaplin pointed out in his autobiography, attempts were made to stop the film being made: "Half-way through making The Great Dictator I began receiving alarming messages from United Artists. They had been advised by the Hays Office that I would run into censorship trouble. Also the English office was very concerned about an anti-Hitler picture and doubted whether it could be shown in Britain. But I was determined to go ahead, for Hitler must be laughed at." However, by the time The Great Dictator was finished, Britain was at war with Germany and it was used as propaganda against Adolf Hitler.

During the Second World War Chaplin played an active role in the American Committee for Russian War Relief. Others involved in this organization included Fiorello La Guardia, Vito Marcantonio, Wendell Willkie, Orson Welles, Rockwell Kent and Pearl Buck. Chaplin was also one of the major figures in the campaign during the summer of 1942 for the opening of a second-front in Europe.

After the Second World War the House of Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC) began to investigate people with left-wing views in the entertainment industry. In September 1947 Chaplin was subpoenaed to appear before the HUAC but three times his meeting was postponed. Unknown to Chaplin, J. Edgar Hoover, and the FBI, now had a 1,900 page file on his political activities. Hoover advised the Attorney General that when Chaplin left the country he should be allowed to return.

In 1952 Chaplin visited London for the premiere of Limelight. When he arrived back he discovered his entry permit revoked and had been denied the right to live in the United States. As Chaplin pointed out in his autobiography: "My prodigious sin was, and still is, being a non-conformist. Although I am not a Communist I refused to fall in line by hating them."

Chaplin, blacklisted from making films in Hollywood, responded by making A King in New York (1957). The film stars Chaplin as the deposed king of Estrovia who flees to America where he is tormented by McCarthy style investigations. Chaplin was once again accused of being pro-communist and the film was not released in the United States.

While in exile, Chaplin wrote his memoirs, My Autobiography (1964) and directed the movie, A Countess from Hong Kong (1966). Despite the objections of J. Edgar Hoover, in 1972 Chaplin was invited back to the United States to receive a special award from the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences. He was also allowed to distribute his satire on McCarthyism, A King in New York.

Charlie Chaplin died in Switzerland on 25th December, 1977.

On this day in 1911 Soviet spy Guy Burgess, the elder son of Commander Malcolm Kingsford de Moncy Burgess and his wife, Evelyn Mary, was born in Devonport, Devon. Burgess's father died in 1924 and his mother later married John Retallack Bassett, a retired lieutenant-colonel.

Burgess went to Eton College where he was taught history by Robert Birley. He later recalled: "He (Burgess) had a gift for plunging to the root of any question and his essays were on occasion full of insights. His career in the upper school passed wholly without blemish. No evidence whatever of any weaknesses or defects of character came to light."

Burgess won an open scholarship to read modern history at Trinity College. According to Phillip Knightley, the author of Philby: KGB Masterspy (1988): "He (Burgess had come up from Eton to Trinity in 1930, set the university buzzing with his homosexual exhibitionism, and had been elected an Apostle, a mark of outstanding and all-round distinction. (The Apostles was a mixture of a dining club and a secret society which divided itself between King's, its spiritual home, and Trinity, where it had many members.).

Burgess joined the Cambridge University Socialist Society (CUSS) and most of his new friends held left-wing views. This included Kim Philby, Anthony Blunt, Donald Maclean and James Klugmann. At university he was described as "amoral, witty, supremely dangerous and loud in his advocacy of communism." It has been claimed that Maurice Dobb recruited Burgess to the Communist Party of Great Britain in November 1932. Over the next two years he managed to inject into the CUSS's "debates a note of passionate left-wing political content to replace the usual literary, artistic and philosophical subjects."

Robert Birley claimed that when he visited Burgess at university in 1931: "Guy wasn't in when I arrived so I entered his room in New Court and waited (during the summer of 1931). There were many books on his shelves, and I'm always drawn to other people's taste in reading. As I expected, his taste was fairly wide and interesting. I noticed a number of Marxist tracts and textbooks, but that's not what really shocked and depressed me. I realized that something must have gone terribly wrong when I came across an extraordinary array of explicit and extremely unpleasant pornographic literature. He bustled in finally, full of cheerful apologies for being late as usual, and we talked happily enough over the tea-cups."

According to John Costello, the author of Mask of Treachery (1988), Blunt became very close to Guy Burgess: "Blunt was intensely fond of Burgess, and his personal loyalty never wavered... Burgess and Blunt did not share a lifelong sexual passion for each other, according to other bedmates... Such evidence as there is confirms that their intimacy quickly outgrew the bedroom. This was in keeping with the character of Burgess and his insatiable sexual appetite... Burgess had a peculiar talent for transforming his former lovers into close friends. To many of them, including Blunt, he became both father confessor and pimp who could be relied on to procure partners. Burgess devoured sex as he did alcohol - an over-indulgence that suggests he was drowning a deep sense of sexual inadequacy."

Burgess gained a first in part one of the history tripos (1932) and an aegrotat in part two (1933), and held a two-year postgraduate teaching fellowship. Although his friends admired his intelligence and wit he made a lot of enemies: "He (Burgess) had epigrammjatic wit and an air of omniscience which belied his years; yet his goatlike agility of mind went with an unguarded tongue. He would utter malicious and wounding comments at the drop of a hat against anyone blocking the maze of intersecting paths he followed."

In January 1934 Arnold Deutsch, one of NKVD's agents, was sent to London. As a cover for his spying activities he did post-graduate work at London University. In May he made contact with Litzi Friedmann and Edith Tudor Hart. They discussed the recruitment of Soviet spies. Litzi suggested her husband, Kim Philby. "According to her report on Philby's file, through her own contacts with the Austrian underground Tudor Hart ran a swift check and, when this proved positive, Deutsch immediately recommended... that he pre-empt the standard operating procedure by authorizing a preliminary personal sounding out of Philby."

Kim Philby later recalled that in June 1934. "Lizzy came home one evening and told me that she had arranged for me to meet a 'man of decisive importance'. I questioned her about it but she would give me no details. The rendezvous took place in Regents Park. The man described himself as Otto. I discovered much later from a photograph in MI5 files that the name he went by was Arnold Deutsch. I think that he was of Czech origin; about 5ft 7in, stout, with blue eyes and light curly hair. Though a convinced Communist, he had a strong humanistic streak. He hated London, adored Paris, and spoke of it with deeply loving affection. He was a man of considerable cultural background."

Deutsch asked Philby if he was willing to spy for the Soviet Union: "Otto spoke at great length, arguing that a person with my family background and possibilities could do far more for Communism than the run-of-the-mill Party member or sympathiser... I accepted. His first instructions were that both Lizzy and I should break off as quickly as possible all personal contact with our Communist friends." It is claimed by Christopher Andrew, the author of The Defence of the Realm: The Authorized History of MI5 (2009) that Philby became the first of "the ablest group of British agents ever recruited by a foreign intelligence service."

Arnold Deutsch asked Kim Philby to make a list of potential recruits. The first person he approached was his friend, Donald Maclean, who had been a fellow member of the Cambridge University Socialist Society (CUSS) and now working in the Foreign Office. Philby invited him to dinner, and hinted that there was important clandestine work to be done on behalf of the Soviet Union. He told him that "the people I could introduce you to are very serious." Maclean agreed to met Deutsch. He was told to carry a book with a bright yellow cover into a particular café at a certain time. Deutsch was impressed with Maclean who he described as being "very serious and aloof" with "good connections". Maclean was given the codename "Orphan". Maclean was also ordered to give up his communist friends.

In May 1934 Philby arranged for Deutsch to meet Guy Burgess. At first Deutsch rejected Burgess as a potential spy. He reported to headquarters that Burgess was "very smart... but a bit superficial and could let slip in some circumstances." Burgess began to suspect that his friend Maclean was working for the Soviets. He told Maclean: "Do you think that I believe for even one jot that you have stopped being a communist? You're simply up to something." When Maclean told Deutsch about the conversation, he reluctantly signed him up. Burgess went around telling anyone who would listen that he had swapped Karl Marx for Benito Mussolini and was now a devotee of Italian fascism. Burgess along with Philby joined the also joined the Anglo-German Fellowship, a pro-fascist society formed in 1935 to foster closer understanding with Adolf Hitler.

Burgess now suggested the recruitment of one of his friends, Anthony Blunt. According to Blunt's biographer, Michael Kitson: "Blunt - hitherto the image of an elegant, apolitical, social young academic - began to take an interest in Marxism under the influence of his friend the charming, scandalous Guy Burgess, a fellow Apostle, who had recently converted to communism. Blunt's move to the left can be plotted in his art reviews, in which he turned from a Bloomsbury acolyte into an increasingly dogmatic defender of social realism. He eventually came to attack even his favourite contemporary artist, Picasso, for the painting Guernica's insufficient incorporation of communism."

Other friends, John Cairncross and Michael Straight were also recruited during this period. Arnold Deutsch handled recruitment but much of the day-to-day management of the spies were carried out by another agent, Theodore Maly. Born in Timişoara, Romania, he studied theology and became a priest but on the outbreak of the First World War he joined the Austro-Hungarian Army. He told Elsa Poretsky, the wife of Ignaz Reiss: "During the war I was a chaplain, I had just been ordained as a priest. I was taken prisoner in the Carpathians. I saw all the horrors, young men with frozen limbs dying in the trenches. I was moved from one camp to another and starved along with other prisoners. We were all covered with vermin and many were dying of typhus. I lost my faith in God and when the revolution broke out I joined the Bolsheviks. I broke with my past completely. I was no longer a Hungarian, a priest, a Christian, even anyone's son. I became a Communist and have always remained one."

As Ben Macintyre, the author of A Spy Among Friends (2014), has pointed out: "For a spy, Maly was conspicuous, standing six feet four inches tall, with a shiny grey complexion", and gold fillings in his front teeth. But he was a most subtle controller, who shared Deutsch's admiration for Philby." Maly described Philby as "an inspirational figure, a true comrade and idealist." According to Deutsch: "Both of them (Philby and Maly) were intelligent and experienced professionals, as well as genuinely very good people."

Christopher Andrew has argued in his book, The Defence of the Realm: The Authorized History of MI5 (2009): "KGB files credit Deutsch with the recruitment of twenty agents during his time in Britain. The most successful, however, were the Cambridge Five: Philby, Maclean, Burgess, Blunt and Cairncross.... All were committed ideological spies inspired by the myth-image of Stalin's Russia as a worker-peasant state with social justice for all rather than by the reality of a brutal dictatorship with the largest peacetime gulag in European history. Deutsch shared the same visionary faith as his Cambridge recruits in the future of a human race freed from the exploitation and alienation of the capitalist system. His message of liberation had all the greater appeal for the Five because it had a sexual as well as a political dimension. All were rebels against the strict sexual mores as well as the antiquated class system of inter war Britain. Burgess and Blunt were gay and Maclean bisexual at a time when homosexual relations, even between consenting adults, were illegal. Cairncross, like Philby a committed heterosexual, later wrote a history of polygamy."

Guy Burgess had a wide variety of different jobs. A friend from university, Victor Rothschild, introduced Burgess to his mother, Rozsika Rothschild. She engaged him at £100 a month to give her advice about her investments. "This was a sum five times what his contemporaries were earning, and the effort needed to earn it was so slight it left him time for other enterprises." (23) Burgess made three visits to Nazi Germany. This included a "fact-finding group" that included the right-wing Conservative Party MP, Captain John Macnamara, a fellow member of the Anglo-German Fellowship. They concluded that the Nazi government was doing a great job for Germany.

In October 1936 Burgess was appointed to a post at the Talks Department of the BBC. This brought him into contact with senior British politicians. In March 1938 he was a courier between Neville Chamberlain and Edouard Daladier, and in September he urged Winston Churchill to repeat his warning against Adolf Hitler to Joseph Stalin. Churchill developed a friendship with Burgess and he gave him a signed copy of Churchill's Arms and the Covenant (1938). Burgess used his influence to arrange for friends Anthony Blunt and E. H. Carr to broadcast on the BBC.

In December 1938 Burgess joined the British secret service. According to Chapman Pincher, the author of Their Trade is Treachery (1981) Major George Joseph Ball was involved in the reorganization of the Security Service after the departure of Vernon Kell in the summer of 1940. This included the recruitment of his old friend Guy Burgess into MI5. Burgess posed as a right-wing Conservative but was really a Soviet spy and part of the network that included Kim Philby, Anthony Blunt, Donald Maclean and James Klugmann. "Burgess used this friendly contact to infiltrate his way into MI5."

Burgess was appointed to section D of MI6, dedicated to sabotage and subversion. He became close to Guy Liddell and other senior officers. Burgess had become a member of the establishment. As Phillip Knightley, the author of Philby: KGB Masterspy (1988) has pointed out: "They considered themselves a class apart... Who else would have tolerated the drunken, aggressive, dirty, drug-taking Guy Burgess, seducer of sailors, lorry drivers and chorus boys, except the Bentinck Street clan who saw beyond his appalling facade into a brilliant and original intellect."

In December 1946 Burgess became private secretary to Hector McNeil, then minister of state at the Foreign Office. According to his biographer, Sheila Kerr, "Burgess... excitedly he told his Soviet controller about his rapid and sensational advance to the centre of British foreign and defence policy-making. Regarded as an expert on communism and with experience in propaganda, he was appointed to the information research department (IRD), a secret unit created to combat Soviet propaganda."

In December 1947 Burgess moved to the Information Research Department. The following year he joined the Far Eastern Department. On a holiday in Tangier he had been heard talking with wild indiscretion in a bar by a member of the local SIS station. "Astonishingly, as it may now seem, his transfer to Washington was considered to be a punishment for this misdemeanour. Fearing they would suffer the worst of the punishment, members of the embassy staff who knew something of Burgess resisted his appointment, but to no avail, and after his name had been buck-passed round the offices for a time, he was eventually detailed to Middle East affairs, a subject of which he knew nothing."

When he arrived in Washington, Kim Philby suggested to his wife, Aileen Philby, that Burgess should live in the basement of their house. Nicholas Elliott explained that Aileen was completely opposed to the idea. "Knowing the trouble that would inevitably ensue - and remembering Burgess's drunken and homosexual orgies when he had stayed with them in Instanbul - Aileen resisted this move, but bowed in the end (and as usual) to Philby's wishes... The inevitable drunken scenes and disorder ensued and tested the marriage to its limits."

Meredith Gardner and his code-breaking team at Arlington Hall discovered that a Soviet spy with the codename of Homer was found on a number of messages from the KGB station at the Soviet consulate-general in New York City to Moscow Centre. The cryptanalysts discovered that the spy had been in Washington since 1944. The FBI concluded that it could be one of 6,000 people. At first they concentrated their efforts on non-diplomatic employees of the embassy. In April 1951, the Venona decoders found the vital clue in one of the messages. Homer had had regular contacts with his Soviet control in New York, using his pregnant wife as an excuse. This information enabled them to identify the spy as Donald Maclean, the first secretary at the Washington embassy during the Second World War.

Kim Philby was told of the breakthrough. Philby took the news calmly as there was no real evidence, as yet, to connect him directly with Maclean, and the two men had not met for several years. MI5 decided not to arrest Maclean straight away. The Venona material was too secret to be used in court and so it was decided to keep Maclean under surveillance in the hope of gathering further evidence, for example, catching him in direct contact with his Soviet controller. Philby relayed the news to Moscow and demanded that Maclean be extracted from the UK before he was interrogated and compromised the entire British spy network.

Philby made the decision to use Guy Burgess to warn Maclean that he must flee to Moscow. The two men dined in a Chinese restaurant in downtown Washington, selected because it had individual booths with piped music, to prevent any eavesdroppers. Burgess said he would return to London in order to receive details of the escape plan. Before he left Philby made Burgess promise he would not flee with Maclean to Moscow: "Don't go with him when he goes. If you do, that'll be the end of me. Swear that you won't." Philby was aware that if Burgess went with Maclean, he would be suspected as a member of the network.

He arrived back in England on 7th May 1951, and immediately contacted Anthony Blunt, who got a message to Yuri Modin, the Soviet controller of the Philby network. Blunt told Modin: "There's serious trouble, Guy Burgess has just arrived back in London. Homer's about to be arrested... It's only a question of days now, maybe hours... Donald's now in such a state that I'm convinced he'll break down the moment they arrest him."

After receiving instructions from his superiors, Modin arranged for Maclean to escape to the Soviet Union. Modin was informed that Maclean would be arrested on 28th May. The plan was for Maclean to be interviewed by the Foreign Secretary, Herbert Morrison. "It has been assumed that Morrison held a meeting and that someone present at that meeting tipped off Burgess." Another possibility is that a senior figure in MI5 was a Soviet spy, and he told Modin of the plan to arrest Maclean. This is the view of Peter Wright who suspects it was Roger Hollis who provided Modin with the information.

On 25th May 1951, Burgess appeared at the Maclean's home in Tatsfield with a rented car, packed bags and two round-trip tickets booked in false names for the Falaise, a pleasure boat leaving that night for St Malo in France. Modin had insisted that Burgess must accompany Maclean. He later explained: "The Centre had concluded that we had not one, but two burnt-out agents on our hands on our hands. Burgess had lost most of his former value to us... Even if he retained his job, he could never again feed intelligence to the KGB as he had done before. He was finished."

Maclean and Burgess took a train to Paris, and then another train to Berne in Switzerland. They then picked up fake passports in false names from the Soviet embassy. They then took another train to Zurich, where they boarded a plan bound for Stockholm, with a stopover in Prague. They left the airport and now safely behind the Iron Curtain, they were taken by car to Moscow.

Melinda Maclean informed the Foreign Office on Monday, 28th May 1951, that her husband had gone missing. It was soon discovered that Burgess had also gone missing. The Foreign Office sent out an urgent telegram to embassies and MI6 stations throughout Europe, with instructions that Burgess and Maclean be apprehended "at all costs and by all means". A Missing Persons poster gave a description of the fugitives: "Maclean: 6 feet 3 inches, normal build, short hair, brushed back, part on left side, slight stoop, thin tight lips, long thin legs, sloppy dressed, chain smoker, heavy drinker. Burgess: 5 feet 9 inches, slender build, dark complexion, dark curly hair, tinged with grey, chubby face, clean shaven, slightly pigeon-toed."

Guy Burgess worked in the Foreign Languages Publishing House. Isolated in Moscow, where homosexuality was not officially tolerated, he turned to drink. He died from a heart attack following liver failure, in the Botin Hospital, Moscow, on 30th August 1963. Burgess left his 4,000 book library to Kim Philby.

On this day in 1912 Elsie Inglis, a member of the National Union of Suffrage Societies, delivers lecture on "Women's Suffrage and the Present Political Situation".

On this day in 1939, the Soviet Union suggested a three-power military alliance with Great Britain and France. Neville Chamberlain did not like the idea. He wrote to a friend: "I must confess to the most profound distrust of Russia. I have no belief whatever in her ability to maintain an effective offensive, even if she wanted to. And I distrust her motives, which seem to me to have little connection with our ideas of liberty, and to be concerned only with getting everyone else by the ears."

After the successful invasion of Czechoslovakia, Hitler began to make demands on the Polish government. This included a request for the return of the free city of Danzig and the amendment of the Polish corridor. Not surprisingly, Poland called on the British government for help. On 24th April, 1939, Colonel Józef Beck, the Polish foreign minister, arrived in London and proposed a secret understanding involving Britain, France and Poland. Chamberlain welcomed the suggestion as he wanted to pursue a policy of deterrence, without extreme provocation."

The guarantee to Poland, which France joined, was officially announced on 31st March, 1939. David Lloyd George, immediately objected to the agreement. As he pointed out: "If war occurred tomorrow, you could not send a single battalion to Poland." Chamberlain responded that he believed the guarantee would point "not towards war, which wins nothing or settles nothing, cures nothing, ends nothing" but would open the way towards "a more wholesome era, when reason will take place of force."

On 13th April, further Anglo-French guarantees were offered to Rumania, Greece and Turkey. The following week the government introduced conscription for all males aged twenty and twenty-one. It also announced that spending limits on the army, navy and air force were abandoned and a ministry of supply to co-ordinate the supply of war materials was established. Hitler and Mussolini responded by signing a military alliance - the Pact of Steel - which added further to the idea of an inevitable war.

The chiefs of staff supported the idea of an Anglo-Soviet alliance. On 16th May, Ernle Chatfield, 1st Baron Chatfield, Minister for Coordination of Defence, strongly urged the conclusion of an Anglo-Soviet agreement. He warned that if the Soviet Union stood aside in a European war it might "secure an advantage from the exhaustion of the western powers" and that if negotiations failed, a Nazi-Soviet agreement was a strong possibility. Chamberlain rejected the advice and said he preferred to "extend our guarantees" in eastern Europe rather than sign an Anglo-Soviet alliance.

A debate on the subject took place in the House of Commons on 19th May, 1939. The debate was short and was "practically confined to the leaders of Parties and to prominent ex-Ministers". Chamberlain made it clear that he had severe doubts about Stalin's proposal. David Lloyd George, the former prime minister called for an alliance with the Soviet Union. Clement Attlee had been campaigning for a military alliance with the Soviet Union since September, 1938, during the crisis over Czechoslovakia. Attlee argued in the House of Commons that the government should form a "firm union between Britain, France and the USSR as the nucleus of a World Alliance against aggression". The government was "dilatory and fumbling" and was in danger of letting Stalin slip out of their grasp and into Hitler's hands."

Winston Churchill, made a passionate speech where he urged Chamberlain to accept Stalin's offer: "There is no means of maintaining an eastern front against Nazi aggression without the active aid of Russia. Russian interests are deeply concerned in preventing Herr Hitler's designs on eastern Europe. It should still be possible to range all the States and peoples from the Baltic to the Black sea in one solid front against a new outrage of invasion. Such a front, if established in good heart, and with resolute and efficient military arrangements, combined with the strength of the Western Powers, may yet confront Hitler, Goering, Himmler, Ribbentrop, Goebbels and co. with forces the German people would be reluctant to challenge."

On 24th May, 1939, the Cabinet discussed whether to open negotiations for an Anglo-Soviet alliance. The Cabinet was overwhelmingly in favour of an agreement. This included Lord Halifax who feared that if Britain did not do so the Soviet Union would sign an alliance with Nazi Germany. Chamberlain conceded that "in present circumstances, it was impossible to stand out against the conclusion of an agreement" but he stressed the "question of presentation was of the utmost importance." He therefore insisted that attempts should be made to hide any agreement under the banner of the League of Nations.

In June, 1939, a public opinion poll showed that 84 per cent of the British public favoured an Anglo-French-Soviet military alliance. Negotiations progressed very slowly and it has been claimed by Frank McDonough, the author of Neville Chamberlain, Appeasement and the British Road to War (1998), that "Chamberlain did not seem to care less whether an Anglo-Soviet agreement was signed at all, kept placing obstructions in the way of concluding an agreement swiftly." Chamberlain admitted: "I am so sceptical of the value of Russian help that I should not feel that our position was greatly worsened if we had to do without them."

Stalin's own interpretation of Britain's rejection of his plan for an anti-fascist alliance, was that they were involved in a plot with Germany against the Soviet Union. This belief was reinforced when Chamberlain met with Adolf Hitler at Munich and gave into his demands for the Sudetenland in Czechoslovakia. Stalin now believed that the main objective of British foreign policy was to encourage Germany to head east rather than west. Stalin now decided to develop a new foreign policy. Stalin realized that war with Germany was inevitable. However, to have any chance of victory he needed time to build up his armed forces. The only way he could obtain time was to do a deal with Hitler. Stalin was convinced that Hitler would not be foolish enough to fight a war on two fronts. If he could persuade Hitler to sign a peace treaty with the Soviet Union, Germany was likely to invade Western Europe instead.

Stalin was frustrated by the British approach and dismissed Maxim Litvinov, his Jewish Commissar for Foreign Affairs. Litvinov had been closely associated with the Soviet Union's policy of an anti-fascist alliance. Time Magazine reported that there were several possible reasons for the replacement of Litvinov with Vyacheslav Molotov. "Most ominous - and least likely - explanation of the change: Comrade Stalin had decided to ally himself with Führer Hitler. Obviously Comrade Litvinov, born of Jewish parents in a Polish town (then Russian), could not be expected to complete such an alliance with rabidly Aryan Nazis. More likely: the Soviet Union was going to follow an isolationist policy (almost as bad for the British and French). By turning isolationist it would let Herr Hitler know that as long as he keeps away from Russia's vast stretches he need not fear the Red Army. Russia might even supply the Nazis with needed raw materials for conquests. Comrade Stalin still hankered after an alliance with Great Britain and France and by dismissing his experienced, alliance-seeking Foreign Commissar was simply trying to scare the British and French into signing up. But the most likely explanation was that in the bluff and counter-bluff of present European diplomacy, Dictator Stalin was simply clearing the decks to be ready at a moment's notice to jump either way."

Walter Krivitsky, a former NKVD agent, who had fled to America in the early months of 1939 was asked by a journalist what he thought were the reasons for Stalin's sacking of Litvinov. He replied, "Stalin has been driven to the parting of roads in his foreign policy and had to choose between the Rome-Berlin axis and the Paris-London axis... Litvinov personified the policy which brought the Soviet government into the League of Nations which raised the slogan of collective security, which raised the slogan of collective security, which claimed to seek collaboration with democratic powers. That policy has collapsed."

However, despite the fact that Krivitsky knew Stalin very well, his warnings were ignored. Negotiations continued between Britain and the Soviet Union. The main stumbling-block concerned the rights of the Soviets to "rescue any Baltic state from Hitler, even if it did not want to be rescued". Britain insisted that they would only cooperate with Soviet Russia if Poland were attacked and agreed to accept Soviet assistance. This deadlock could not be broken and Molotov suggested that they concentrated on military talks. However, the British representatives in the talks were instructed to "go very slowly". The negotiations finally ended in failure on 21st August.

Molotov now began secret negotiations with Joachim von Ribbentrop, the German foreign minister. He later claimed: "To seek a settlement with Russia was my very own idea which I urged on Hitler because I sought to create a counter-weight to the West and because I wanted to ensure Russian neutrality in the event of a German-Polish conflict. After a short ceremonial welcome the four of us sat down at a table: Stalin, Molotov, Count Schulenburg and myself.... Stalin spoke - briefly, precisely, without many words; but what he said was clear and unambiguous and showed that he, too, wished to reach a settlement and understanding with Germany. Stalin used the significant phrase that although we had 'poured buckets of filth' over each other for years there was no reason why we should not make up our quarrel."

On 28th August, 1939, the Nazi-Soviet Pact was signed in Moscow. It was reported: "Late Sunday night - not the usual time for such announcements - the Soviet Government revealed a pact, not with Great Britain, not with France, but with Germany. Germany would give the Soviet Union seven-year 5% credits amounting to 200,000,000 marks ($80.000,000) for German machinery and armaments, would buy from the Soviet Union 180,000.000 marks' worth ($72,000,000) of wheat, timber, iron ore, petroleum in the next two years". Apparently, the day after the agreement was signed, Stalin told Lavrenti Beria: "Of course, it's all a game to see who can fool whom. I know what Hitler's up to. He thinks he's outsmarted me, but actually it's I who have tricked him."

On this day in 1943 Mordechai Anielewicz explains to Yitzhak Zuckerman what life is like in the ghetto. "It is impossible to describe the conditions reigning in the ghetto. Very few could bear all this. All the others are destined to perish sooner or later. Their fate has been sealed. In most of the bunkers where thousands of Jews are hiding it is impossible to light a candle because of the lack of air. What we have experienced cannot be described in words. We are aware of one thing only; what has happened has exceeded our dreams. The Germans ran twice from the ghetto. Perhaps we will meet again. But what really matters is that the dream of my life has come true. Jewish self-defence of the Warsaw ghetto has become a fact. Jewish armed resistance and retaliation have become a reality. I have been witness to the magnificent heroic struggle of the Jewish fighters."

Anielewicz now played a prominent role in organizing resistance in Warsaw. On 19th April 1943, the Waffen SS entered the ghetto. Although though only had two machine-guns, fifteen rifles and 500 pistols, the Jews opened fire on the soldiers. They also attacked them with grenades and petrol bombs. The Germans took heavy casualties on the first day and the Warsaw military commander, Brigadier-General Jürgen Stroop, ordered his men to retreat. He then gave instructions for all the buildings in the ghetto to be set on fire.

As people fled from the fires they were rounded up and deported to the extermination camp at Treblinka. The ghetto fighters continued the battle from the cellars and attics of Warsaw. On 8th May the Germans began using poison gas on the insurgents in the last fortified bunker. About a hundred men and women escaped into the sewers but the rest were killed by the gas, including Mordechai Anielewicz.

On this day in 1955 David Kirkwood died. Kirkwood, the son of a labourer was born in Glasgow, Scotland, in 1872. He left Parkhead Public School at the age of 12 and found work as a message-boy at a local print works. Later he became an apprentice engineer.

In 1891 Kirkwood was converted to socialism by reading Looking Backward by Edward Bellamy. The following year he joined the Amalgamated Society of Engineers (AEU).

Kirkwood joined the Independent Labour Party and served on the Glasgow Trade Council. He remained active in the AEU and was chief shop steward at the Beardmore Works (1914-15).

Kirkwood began working closely with other socialists in Glasgow including John Wheatley, Emanuel Shinwell, James Maxton, William Gallacher, John Muir, Tom Johnston, Jimmie Stewart, Neil Maclean, George Hardie, George Buchanan and James Welsh.

Kirkwood was opposed to Britain becoming involved in the First World War and was an active member of the Union of Democratic Control. He was also treasurer of the Clyde Workers' Committee and organisation that had been formed to campaign against the Munitions Act, which forbade engineers from leaving the works where they were employed. David Lloyd George and Arthur Henderson met Kirkwood and the Clyde Workers' Committee in Glasgow on 25th December 1915 but they were unwilling to back down on the issue.

On 25th March 1916, Kirkwood and other members of the Clyde Workers' Committee were arrested by the authorities under the Defence of the Realm Act. Then men were court-martialled and sentenced to be deported from Glasgow. Kirkwood went to Edinburgh but in January 1917 he travelled to Manchester to speak at the national conference of the Labour Party. On his return to Glasgow he was re-arrested and deported once more to Edinburgh. He remained there until being freed on 30th May 1917.

After the war Kirkwood was involved in the struggle for a 40 hour week. The police broke up an open air trade union meeting at George Square on 31st January, 1919. The leaders of the union were then arrested and charged with "instigating and inciting large crowds of persons to form part of a riotous mob". Emanuel Shinwell was sentenced to five months and William Gallacher got three months. The other ten were found not guilty.

In the 1922 General Election Kirkwood was elected to the House of Commons for Dumbarton Burghs. Also successful were several other militant socialists based in Glasgow including John Wheatley, Emanuel Shinwell, James Maxton, John Muir, Tom Johnston, Jimmie Stewart, Neil Maclean, George Hardie, George Buchanan and James Welsh.

David Kirkwood was one of the leaders of the Independent Labour Party in Parliament until joining the Labour Party in August 1933. Kirkwood published his autobiography, My Life of Revolt in 1935. Kirkwood held his seat in Parliament until 1951 when he was created Baron Kirkwood.

On this day in 1968 Edna Ferber died. Edna Ferber, the daughter of Jacob Ferber, a Jewish storekeeper, and Julia Neumann Ferber, was born in Kalamazoo, Michigan, on 15th August, 1885. When she was a child the family moved to Appleton, Wisconsin, where she attended the local high school. Ferber briefly attended Lawrence University before becoming a journalist on the Appleton Daily Crescent and the Milwaukee Journal.

Ferber's first novel, Dawn O'Hara: The Girl Who Laughed, was published in 1911. This was followed by Buttered Side Down (1912), Roast Beef Medium The Business Adventures Of Emma McChesney (1913), Personality Plus (1914), Our Mrs. McChesney (1915), Fanny Herself (1917), Cheerful – By Request (1918), Half Portions (1919), The Girls (1921) and Gigolo (1922).

Robert E. Sherwood, Dorothy Parker and Robert Benchley all worked at Vanity Fair during the First World War. They began taking lunch together in the dining room at the Algonquin Hotel. Sherwood was six feet eight inches tall and Benchley was around six feet tall, Parker, who was five feet four inches, once commented that when she, Sherwood and Benchley walked down the street together, they looked like "a walking pipe organ." Ferber became friends with this small group and would sometimes have lunch with them in the hotel.

According to Harriet Hyman Alonso , the author of Robert E. Sherwood The Playwright in Peace and War (2007): "John Peter Toohey, a theater publicist, and Murdock Pemberton, a press agent, decided to throw a mock "welcome home from the war" celebration for the egotistical, sharp-tongued columnist Alexander Woollcott. The idea was really for theater journalists to roast Woollcott in revenge for his continual self-promotion and his refusal to boost the careers of potential rising stars on Broadway. On the designated day, the Algonquin dining room was festooned with banners. On each table was a program which misspelled Woollcott's name and poked fun at the fact that he and fellow writers Franklin Pierce Adams (F.P.A.) and Harold Ross had sat out the war in Paris as staff members of the army's weekly newspaper, the Stars and Stripes, which Bob had read in the trenches. But it is difficult to embarrass someone who thinks well of himself, and Woollcott beamed at all the attention he received. The guests enjoyed themselves so much that John Toohey suggested they meet again, and so the custom was born that a group of regulars would lunch together every day at the Algonquin Hotel."

Murdock Pemberton later recalled that he owner of the hotel, Frank Case, did what he could to encourage this gathering: "From then on we met there nearly every day, sitting in the south-west corner of the room. If more than four or six came, tables could be slid along to take care of the newcomers. we sat in that corner for a good many months... Frank Case, always astute, moved us over to a round table in the middle of the room and supplied free hors d'oeuvre.... The table grew mainly because we then had common interests. We were all of the theatre or allied trades." Case admitted that he moved them to a central spot at a round table in the Rose Room, so others could watch them enjoy each other's company.

The people who attended these lunches included Ferber, Robert E. Sherwood, Dorothy Parker, Robert Benchley, Alexander Woollcott, Heywood Broun, Harold Ross, Donald Ogden Stewart, Ruth Hale, Franklin Pierce Adams, Jane Grant, Neysa McMein, Alice Duer Miller, Charles MacArthur, Marc Connelly, George S. Kaufman, Beatrice Kaufman , Frank Crowninshield, Ben Hecht, John Peter Toohey, Lynn Fontanne, Alfred Lunt and Ina Claire. This group eventually became known as the Algonquin Round Table.

Edna Ferber wrote about her membership of the group in her book, A Peculiar Treasure (1939): "The contention was that this gifted group engaged in a log-rolling; that they gave one another good notices, praise-filled reviews and the like. I can't imagine how any belief so erroneous ever was born. Far from boosting one another they actually were merciless if they disapproved. I never have encountered a more hard-bitten crew. But if they liked what you had done they did say so, publicly and wholeheartedly. Their standards were high, their vocabulary fluent, fresh, astringent and very, very tough. Theirs was a tonic influence, one on the other, and all on the world of American letters. The people they could not and would not stand were the bores, hypocrites, sentimentalists, and the socially pretentious. They were ruthless towards charlatans, towards the pompous and the mentally and artistically dishonest. Casual, incisive, they had a terrible integrity about their work and a boundless ambition."

Ferber had her first major success with her novel, So Big, which was awarded the Pulitzer Prize in 1924. Later that year Ferber began writing plays another member of the Algonquin Round Table, the former journalist, George S. Kaufman. The author of George S. Kaufman: An Intimate Portrait (1972) has argued: "In many ways she was very much like Kaufman: middle-western birthplace, same German-Jewish background, same training as a newspaper reporter, same discipline toward work. In other ways she was the direct opposite of Kaufman. She was small in physical stature, and a great believer in exercise. She had great personal courage, an overwhelming desire to travel, to seek new people, new places, new ideas. She did not have Kaufman's wit, but she did have the ability to write rich, deep love scenes."

Their first play together was Minnick . It opened at the Booth Theatre on 24th September, 1924 and ran for 141 performances. Alexander Woollcott said that the play "loosed vials of vitriol out of all proportion to the gentle little play's importance." Feber replied that she found the review "just that degree of malignant poisoning that I always find so stimulating in the works of Mr. Woollcott". This led to a long-running dispute between the two former friends. Woollcott's biographer, Samuel Hopkins Adams, claims that it started as "the inevitable bickerings which are bound to occur between two highly sensitized temperaments."

This was followed by Show Boat (1926). This was turned into a popular musical by Jerome Kern and Oscar Hammerstein II, that featured Paul Robeson. She also continued to write with Kaufman. Their next play, The Royal Family, was based on the lives of Ethel Barrymore, John Barrymore and Lionel Barrymore. It took eight months to write and after being cleared by the Barrymore family lawyers it opened at the Selwyn Theatre on 28th December, 1927. Produced by Jed Harris and directed by David Burton, it was a great success and ran for 345 performances.

They were unable to recapture this success and eventually broke up the writing partnership. Ferber later admitted that she was always afraid of George S. Kaufman and they had a difficult relationship. "When he needled you, it was like a cold knife that he stuck into your ribs. And he did it so fast, so quickly, you didn't even see it go in. You only felt the pain." Kaufman told his friends that he lived in mortal fear of Ferber. He disliked her temper and her love of quarrels.

Feber's next novel, Cimarron (1929), about the Oklahoma Land Rush, was later turned into the Academy Award winning film of the same name. Ferber held left-wing political views and campaigned for Heywood Broun when he stood as a candidate for the Socialist Party of America in 1930. She was also a member of the Progressive Citizens of America (PCA). Its members included Henry A. Wallace, Rexford Tugwell, Paul Robeson, W.E.B. Du Bois, Arthur Miller, Dashiell Hammett, Hellen Keller, Thomas Mann, Aaron Copland, Claude Pepper, Eugene O'Neill, Glen H. Taylor, John Abt, Thornton Wilder, Carl Van Doren, Fredric March and Gene Kelly.

The playwright, Howard Teichmann, claims that Ferber's difficult relationship with Alexander Woollcott became worse after the events that took place on the opening night of The Dark Tower in 1933. "Woollcott, who knew how capricious opening-night audiences could be, decided not to have the usual crowd. Instead, he selected 250 of his personal friends to fill the better part of the orchestra floor at the Morosco Theatre. Two pairs of seats went to his old pal Edna Ferber. Escorted that night by the millionaire diplomat Stanton Griffis, Miss Ferber had as guests the Hollywood motion-picture star Gary Cooper and his wife. At curtain time Miss Ferber and party had not arrived at the theater, and the house lights went down on four choice but empty seats... Aleck waddled into the lobby only to find Ferber and her party standing there while Gary Cooper gave autographs to movie fans."

The actress Margalo Gillmore later recalled that after the play had finished they all met in her dressing room. "Woollcott, Ferber, Stanton Griffis, poor Beatrice Kaufman. Woollcott glared and glared and his eyes through those thick glasses he wore seemed as big as the ends of the old telephone receivers. Ice dripped everywhere." Teichmann added that Woollcott "who felt the greatest gift he could bestow was his own presence, gave his ultimatum" that he would "never go on the Griffis yacht again".

A few weeks later, Ferber, still upset by Woollcott's behaviour that night, referred to Woollcott as "That New Jersey Nero who thinks his pinafore is a toga." When he heard about the comment, Woollcott responded with the comment: "I don't see why anyone should call a dog a bitch when there's Edna Ferber around." Howard Teichmann claims that "they never spoke after that".

Other books by Ferber included American Beauty (1931), They Brought Their Women (1933) and Come and Get It (1935). Nobody's in Town (1938), A Peculiar Treasure (1939), The Land Is Bright (1941), Saratoga Trunk (1941), No Room at the Inn (1941), Great Son (1945), Giant (1952), Ice Palace (1958) and A Kind of Magic (1963).

Edna Ferber never married. She once wrote: "Life can't defeat a writer who is in love with writing, for life itself is a writer's lover until death." On another occasion she remarked: "Being an old maid is like death by drowning, a really delightful sensation after you cease to struggle." It is claimed that she had always been in love with George S. Kaufman. However, they often had disagreements when they were together. In 1960 he wrote to her. "I am an old man and not well. I have had two or three strokes already and I cannot afford another argument with you to finish my life. So I simply wish to end our friendship." After waiting a sensible amount of time, she telephoned him and they agreed to see each other again. He died in 1961.

On this day in 1978 Lucius D. Clay, died in Chatham, Massachusetts. Luicius Clay was born in Marietta, Georgia, on 23rd April, 1896. He attended the West Point Military Academy and after graduation was commissioned in the Corps of Engineers.

In 1933 Clay allied himself with Harry Hopkins and became a strong supporter of Franklin D. Roosevelt and the New Deal. In 1939 Clay organized the building of the Denison Dam Red River.

In June, 1940, Clay became head of the emergency Defence Airport Program and organized the building or expanding over 250 airports before the United States entered the Second World War.

Clay remained in Washington for most of the war as Director of War Department Material. He also served on the Munitions Assignment Board and the War Production Board.

In July, 1944, Clay was also a delegate to the Bretton Woods conference. Soon afterwards he was sent to France to become supply chief under Dwight D. Eisenhower. The following year he was appointed Eisenhower's deputy as military governor of occupied Germany.

In May, 1946 Clay became military governor of Germany. He held the post during the Berlin Airlift and was replaced by John J. McCloy in 1949.

Clay retired from the United States Army in 1949 and went into industry and worked as Chief Executive Officer of Continental Can and Lehman Brothers, the investment bankers.

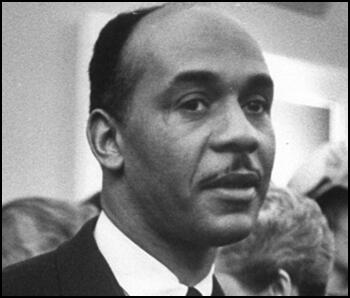

On this day in 1994 Ralph Ellison died. Ralph Ellison, the son of Lewis Alfred Ellison and Ida Millsap, was born in Oklahoma City, on 1st March, 1914. It was later claimed that he was named after Ralph Waldo Emerson. Ralph's father, who ran a small business, died when he was only three years old.

In 1933 Ellison won a scholarship to study music at the Tuskegee Institute in Alabama, where he was taught by two very talented musicians, William Levi Dawson and Hazel Harrison. He also spent a lot of time in the library reading and eventually decided to become a writer.

Ellison joined the Federal Writers' Project in New York City in 1936. He met Richard Wright who encouraged him and published some of his short stories and reviews in New Challenge and the Negro Quarterly. Other work also appeared in the left-wing journal, New Masses, where he mixed with other radical writers and artists such as Max Eastman, Upton Sinclair, Sherwood Anderson, Erskine Caldwell, Alvah Bessie, James Agee, Langston Hughes, John Dos Passos, Josephine Herbst, Albert Maltz, Agnes Smedley, Theodore Dreiser, Floyd Dell, Art Young, William Gropper, Albert Hirschfeld, Carl Sandburg, Waldo Frank and Eugene O'Neill.

During the Second World War Ellison served in the Merchant Marine. With the support of his second wife, Fanny McConnell, who worked as a photographer, Ellison spent his time on his first novel, Invisible Man (1952). The book tells the story of a Southern black youth who goes to Harlem to join the fight against white oppression. The book was well received and won the National Book Award in 1953.

Irving Howe wrote: "No white man could have written it, since no white man could know with such intimacy the life of the Negroes from the inside; yet Ellison writes with an ease and humor which are now and again simply miraculous. Invisible Man is a record of a Negro's journey through contemporary America, from South to North, province to city, naive faith to disenchantment and perhaps beyond. There are clear allegorical intentions but with a book so rich in talk and drama it would be a shame to neglect the fascinating surface for the mere depths."

Saul Bellow added: "He (the main character in the novel) is recruited by white radicals and becomes a Negro leader, and in the radical movement he learns eventually that throughout his entire life his relations with other men have been schematic; neither with Negroes nor with whites has he ever been visible, real... one is accustomed to expect excellent novels about boys, but a modern novel about men is exceedingly rare. For this enormously complex and difficult American experience of ours very few people are willing to make themselves morally and intellectually responsible. Consequently, maturity is hard to find."

After the publication of his novel, Ellison travelled around Europe before settling in Rome. However, he was unable to write anything of substance and in 1958 he returned to the United States in order to teach American and Russian literature at Bard College in New York City. He also began work on his second novel, Juneteenth. Although he wrote over 2,000 pages, the novel was never completed. He told friends that he was not satisfied with what he had produced.

Ellison decided to concentrate on his academic career and taught at Rutgers University and Yale University. In 1964, Ellison published Shadow and Act, a collection of essays about life as a black man and his love of jazz. In 1970 he became a permanent member of the faculty at New York University as the Albert Schweitzer Professor of Humanities.

In 1986 he published Going to the Territory, a collection of essays that included studies of Richard Wright, William Faulkner and Duke Ellington. However, he never completed his novel and concentrated on his other interests, including work as a sculptor, musician and photographer.

Ralph Ellison died on 16th April, 1994, of pancreatic cancer. John F. Callahan, his literary executor, arranged the publication of Flying Home and Other Stories in 1996. Three years later he published a 368-page version of his second novel, Juneteenth. The complete version was published as Three Days Before the Shooting in 2010.