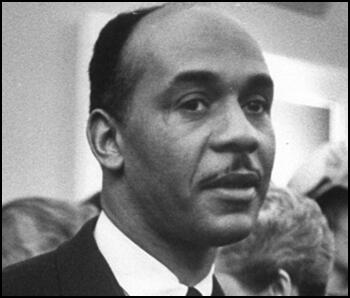

Ralph Ellison

Ralph Ellison, the son of Lewis Alfred Ellison and Ida Millsap, was born in Oklahoma City, on 1st March, 1914. It was later claimed that he was named after Ralph Waldo Emerson. Ralph's father, who ran a small business, died when he was only three years old.

In 1933 Ellison won a scholarship to study music at the Tuskegee Institute in Alabama, where he was taught by two very talented musicians, William Levi Dawson and Hazel Harrison. He also spent a lot of time in the library reading and eventually decided to become a writer.

Ellison joined the Federal Writers' Project in New York City in 1936. He met Richard Wright who encouraged him and published some of his short stories and reviews in New Challenge and the Negro Quarterly. Other work also appeared in the left-wing journal, New Masses, where he mixed with other radical writers and artists such as Max Eastman, Upton Sinclair, Sherwood Anderson, Erskine Caldwell, Alvah Bessie, James Agee, Langston Hughes, John Dos Passos, Josephine Herbst, Albert Maltz, Agnes Smedley, Theodore Dreiser, Floyd Dell, Art Young, William Gropper, Albert Hirschfeld, Carl Sandburg, Waldo Frank and Eugene O'Neill.

During the Second World War Ellison served in the Merchant Marine. With the support of his second wife, Fanny McConnell, who worked as a photographer, Ellison spent his time on his first novel, Invisible Man (1952). The book tells the story of a Southern black youth who goes to Harlem to join the fight against white oppression. The book was well received and won the National Book Award in 1953.

Irving Howe wrote: "No white man could have written it, since no white man could know with such intimacy the life of the Negroes from the inside; yet Ellison writes with an ease and humor which are now and again simply miraculous. Invisible Man is a record of a Negro's journey through contemporary America, from South to North, province to city, naive faith to disenchantment and perhaps beyond. There are clear allegorical intentions but with a book so rich in talk and drama it would be a shame to neglect the fascinating surface for the mere depths."

Saul Bellow added: "He (the main character in the novel) is recruited by white radicals and becomes a Negro leader, and in the radical movement he learns eventually that throughout his entire life his relations with other men have been schematic; neither with Negroes nor with whites has he ever been visible, real... one is accustomed to expect excellent novels about boys, but a modern novel about men is exceedingly rare. For this enormously complex and difficult American experience of ours very few people are willing to make themselves morally and intellectually responsible. Consequently, maturity is hard to find."

After the publication of his novel, Ellison travelled around Europe before settling in Rome. However, he was unable to write anything of substance and in 1958 he returned to the United States in order to teach American and Russian literature at Bard College in New York City. He also began work on his second novel, Juneteenth. Although he wrote over 2,000 pages, the novel was never completed. He told friends that he was not satisfied with what he had produced.

Ellison decided to concentrate on his academic career and taught at Rutgers University and Yale University. In 1964, Ellison published Shadow and Act, a collection of essays about life as a black man and his love of jazz. In 1970 he became a permanent member of the faculty at New York University as the Albert Schweitzer Professor of Humanities.

In 1986 he published Going to the Territory, a collection of essays that included studies of Richard Wright, William Faulkner and Duke Ellington. However, he never completed his novel and concentrated on his other interests, including work as a sculptor, musician and photographer.

Ralph Ellison died on 16th April, 1994, of pancreatic cancer. John F. Callahan, his literary executor, arranged the publication of Flying Home and Other Stories in 1996. Three years later he published a 368-page version of his second novel, Juneteenth. The complete version was published as Three Days Before the Shooting in 2010.

Primary Sources

(1) Ralph Ellison, Invisible Man (1952)

With things going so well I distributed my letters in the mornings, and saw the city during the afternoons. Walking about the streets, sitting on subways beside whites, eating with them in the same cafeterias (although I avoided their tables) gave me the eerie, out-of-focus sensation of a dream. My clothes felt ill-fitting; and for all my letters to men of power, I was unsure of how I should act. For the first time, as I swung along the streets, I thought consciously of how I had conducted myself at home. I hadn't worried too much about whites as people. Some were friendly and some were not, and you tried not to offend either. But here they all seemed impersonal; and yet when most impersonal they startled me by being polite, by begging my pardon after brushing against me in a crowd. Still I felt that even when they were polite they hardly saw me, that they would have begged the pardon of Jack the Bear, never glancing his way if the bear happened to be walking along minding his business. It was confusing. I did not know if it was desirable or undesirable.

(2) Saul Bellow, review of Invisible Man, in Commentary (June, 1952)

A few years ago, in an otherwise dreary and better forgotten number of Horizon devoted to a louse-up of life in the United States, I read with great excitement an episode from Invisible Man. It described a free-for-all of blindfolded Negro boys at a stag party of the leading citizens of a small Southern town. Before being blindfolded the boys are made to stare at a naked white woman; then they are herded into the ring, and, after the battle royal, one of the fighters, his mouth full of blood, is called upon to give his high school valedictorian's address. As he stands under the lights of the noisy room, the citizens rib him and make him repeat himself; an accidental reference to equality nearly ruins him, but everything ends well and he receives a handsome briefcase containing a scholarship to a Negro college.

This episode, I thought, might well be the high point of an excellent novel. It has turned out to be not the high point but rather one of the many peaks of a book of the very first order, a superb book. The valedictorian is himself Invisible Man. He adores the college but is thrown out before long by its president, Dr. Bledsoe, a great educator and leader of his race, for permitting a white visitor to visit the wrong places in the vicinity. Bearing what he believes to be a letter of recommendation from Dr. Bledsoe he comes to New York. The letter actually warns prospective employers against him.

He is recruited by white radicals and becomes a Negro leader, and in the radical movement he learns eventually that throughout his entire life his relations with other men have been schematic; neither with Negroes nor with whites has he ever been visible, real. I think that in reading the Horizon excerpt I may have underestimated Mr. Ellison's ambition and power for the following very good reason, that one is accustomed to expect excellent novels about boys, but a modern novel about men is exceedingly rare. For this enormously complex and difficult American experience of ours very few people are willing to make themselves morally and intellectually responsible. Consequently, maturity is hard to find.

(3) Irving Howe, Black Boys and Native Sons (1963)

What astonishes one most about Invisible Man is the apparent freedom it displays from the ideological and emotional penalties suffered by Negroes in this country. I say "apparent" because the freedom is not quite so complete as the book's admirers like to suppose. Still, for long stretches Invisible Man does escape the formulas of protest, local color, genre quaintness, and jazz chatter.

No white man could have written it, since no white man could know with such intimacy the life of the Negroes from the inside; yet Ellison writes with an ease and humor which are now and again simply miraculous. Invisible Man is a record of a Negro's journey through contemporary America, from South to North, province to city, naive faith to disenchantment and perhaps beyond. There are clear allegorical intentions but with a book so rich in talk and drama it would be a shame to neglect the fascinating surface for the mere depths.