Tuskegee Institute

In 1880, Lewis Adams, a black political leader in Macon County, agreed to help two white Democratic Party candidates, William Foster and Arthur Brooks, win a local election in return for the building of a Negro school in the area. Both men were elected and they then used their influence to secure approval for the building of the Tuskegee Institute.

Samuel Armstrong, principal of the successful Hampton Normal and Agricultural Institute, was asked to recommend a white teacher to take charge of the Tuskegee Institute. However, he suggested that it would be a good idea to employ one of his African American teachers, Booker T. Washington, instead.

The Tuskegee Negro Normal Institute was opened on the 4th July, 1888. The school was originally a shanty building owned by the local church. The school only received funding of $2,000 a year and this was only enough to pay the staff. Eventually Booker T. Washington was able to borrow money from the treasurer of the Hampton Agricultural Institute to purchase an abandoned plantation on the outskirts of Tuskegee and built his own school.

The school taught academic subjects but emphasized a practical education. This included farming, carpentry, brickmaking, shoemaking, printing and cabinetmaking. This enabled students to become involved in the building of a new school. Students worked long-hours, arising at five in the morning and finishing at nine-thirty at night.

By 1888 the school owned 540 acres of land and had over 400 students. Washington was able to attract good teachers to his school such as Olivia Davidson , who was appointed assistant principal, and Adella Logan. Washington's conservative leadership of the school made it acceptable to the white-controlled Macon County. He did not believe that blacks should campaign for the vote, and claimed that blacks needed to prove their loyalty to the United States by working hard without complaint before being granted their political rights.

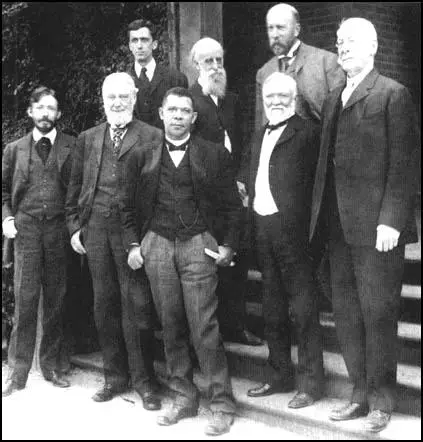

financial supporters at Tuskegee Institute.

Southern whites, who had previously been against the education of African Americans, supported Washington's ideas as they saw them as means of encouraging them to accept their inferior economic and social status. This resulted in white businessmen such as Andrew Carnegie, Seth Low and Collis Huntington donating large sums of money to his school.

In September, 1895, Booker T. Washington became a national figure when his speech at the opening of the Cotton States and International Exposition in Atlanta was widely reported by the country's newspapers. Washington's conservative views made him popular with white politicians who were keen that he should become the new leader of the African American population. To help him in this President William McKinley visited the Tuskegee Institute and praised Washington's achievements.

In 1901, President Theodore Roosevelt invited Washington to visit him in the White House. To southern whites this was going too far. One editor wrote: "With our long-matured views on the subject of social intercourse between blacks and whites, the least we can say now is that we deplore the President's taste, and we distrust his wisdom."

Booker T. Washington now spent most of his time on the lecture circuit. His African American critics who objected to the way Washington argued that it was the role of blacks to serve whites, and that those black leaders who demanded social equality were political extremists.

In 1903 William Du Bois joined the attack on Washington with his essay on his work in The Soul of Black Folks. Washington retaliated with criticisms of Du Bois and his Niagara Movement. The two men also clashed over the establishment of the National Association for the Advancement of Coloured People (NAACP) in 1909.

The following year, William Du Bois and twenty-two other prominent African Americans signed a statement claiming: "We are compelled to point out that Mr. Washington's large financial responsibilities have made him dependent on the rich charitable public and that, for this reason, he has for years been compelled to tell, not the whole truth, but that part of it which certain powerful interests in America wish to appear as the whole truth."

By the time Booker T. Washington died in November, 1915, the Tuskegee Institute had an endowment of $1,945,000, a staff of almost 200, and a student population of 2000.

Primary Sources

(1) Booker T. Washington, Up from Slavery: An Autobiography (1901)

I believe it is the duty of the Negro - as the greater part of the race is already doing - to deport himself modestly in regard of political claims, depending upon the slow but sure influences that proceed from the possessions of property, intelligence, and high character for the full recognition of his political rights. I think that the according of the full exercise of political rights is going to be a matter of natural, slow growth, not an overnight gourdvine affair.

As a rule I believe in universal, free suffrage, but I believe that in the South we are confronted with peculiar conditions that justify the protection of the ballot in many of the states, for a while at least, either by an educational test, a property test, or by both combined; but whatever tests are required, they should be made to apply with equal and exact justice to both races.

(2) William Du Bois, The Souls of Black Folks (1903)

Easily the most striking thing in the history of the American Negro since 1876 is the ascendancy of Mr. Booker T. Washington. It began at the time when war memories and ideals were rapidly passing; a day of astonishing commercial development was dawning; a sense of doubt and hesitation overtook the freedmen's sons - then it was his leading began. His program of industrial education, conciliation of the South, and submission and silence as to civil and political rights, was not wholly original; the Free Negroes from 1830 up to wartime had striven to build industrial schools, and the American Missionary Association had from the first taught various trades. But Mr. Washington first indissolubly linked these things; he put enthusiasm, unlimited energy, and perfect faith into this program, and changed it from a bypath into a veritable Way of Life.

(3) Statement on Booker T. Washington signed by William Du Bois and twenty-two other African Americans (26th October, 1910)

The undersigned Negro-Americans have heard, with great regret, the recent attempt to assure England and Europe that their condition in America is satisfactory. They sincerely wish that such were the case, but it becomes their plan duty to say that Mr. Booker T. Washington, or any other person, is giving the impression abroad that the Negro problem in America is in process of satisfactory solution, he is giving an impression which is not true.

We say this without personal bitterness toward Mr. Washington. He is a distinguished American and has a perfect right to his opinions. But we are compelled to point out that Mr. Washington's large financial responsibilities have made him dependent on the rich charitable public and that, for this reason, he has for years been compelled to tell, not the whole truth, but that part of it which certain powerful interests in America wish to appear as the whole truth.

Today in eight states where the bulk of the Negroes live, black men of property and university training can be, and usually are, by law denied the ballot, while the most ignorant white man votes. This attempt to put the personal and property rights of the best of the blacks at the absolute political mercy of the worst of the whites is spreading each day.

(4) Ray Stannard Baker, American Magazine, Following the Color Line (1908)

Nothing has been more remarkable in the recent history of the Negro than Washington's rise to influence as a leader, and the spread of his ideals of education and progress. It is noteworthy that he was born in the South, a slave, that he knew intimately the common struggling life of the people and the attitude of the white race toward them. The central idea of his doctrine is work. He teaches that if the Negro wins by real worth a strong economic position in the country, other rights and privileges will come to him naturally. He should get his rights, not by gift of the white man, but by earning them himself.

Whenever I found a prosperous Negro enterprise, a thriving business place, a good home, there I was almost sure to find Booker T. Washington's picture over the fireplace or a little framed motto expressing his gospel of work and service. Many highly educated Negroes, especially, in the North, dislike him and oppose him, but he has brought new hope and given new courage to the masses of his race. He has given them a working plan of life. And is there a higher test of usefulness? Measured by any standard, white or black, Washington must be regarded today as one of the great men of this country: and in the future he will be so honored.

(5) Ida Wells was one of the first members of the NAACP. In her autobiography, Crusade for Justice (1928), Wells points out that the NAACP was concerned about the activities of Booker T. Washington in the struggle for racial equality.

There was an uneasy feeling that Mr. Booker T. Washington and his theories, which seemed for the moment to dominate the country, would prevail in the discussion as to what ought to be done. Although the country at large seemed to be accepting and adopting Mr. Washington's theories of industrial education, a large number agreed with Dr. Du Bois that it was impossible to limit the aspirations and endeavors of an entire race within the confines of the industrial education program.