On this day on 10th April

On this day in 1778 William Hazlitt, the son of an Irish Unitarian clergyman, was born in Maidstone, Kent, on 10th April, 1778. His father was a friend of Joseph Priestley and Richard Price. As a result of supporting the American Revolution, Rev. Hazlitt and his family were forced to leave Kent and live in Ireland.

The family returned to England in 1787 and settled at Wem in Shropshire. At the age of fifteen William was sent to be trained for the ministry at New Unitarian College at Hackney in London. The college had been founded by Joseph Priestley and had a reputation for producing freethinkers. In 1797 Hazlitt lost his desire to become a Unitarian minister and left the college.

While in London Hazlitt became friends with a group of writers with radical political ideas. The group included Percy Bysshe Shelley, Samuel Taylor Coleridge, Charles Lamb, William Wordsworth, Thomas Barnes, Henry Brougham, Leigh Hunt, Robert Southey and Lord Byron. At first Hazlitt attempted to become a portrait painter but after a lack of success he turned to writing.

Charles Lamb introduced Hazlitt to William Godwin and other important literary figures in London. In 1805 Joseph Johnson published Hazlitt's first book, An Essay on the Principles of Human Action. The following year Hazlitt published Free Thoughts on Public Affairs, an attack on William Pitt and his government's foreign policy. Hazlitt opposed England's war with France and its consequent heavy taxation. This was followed by a series of articles and pamphlets on political corruption and the need to reform the voting system.

William Hazlitt began writing for The Times and in 1808 married the editor's sister, Sarah Stoddart. His friend, Thomas Barnes, was the newspaper's parliamentary reporter. Later, Barnes was to become the editor of the newspaper. In 1810 he published the New and Improved Grammar of the English Language.

In 1813 Hazlitt was employed as the parliamentary reporter for the Morning Chronicle, the country's leading Whig newspaper. However, in his articles, Hazlitt criticized all political parties. Hazlitt also contributed to The Examiner, a radical journal edited by Leigh Hunt. Later, Hazlitt wrote for the Edinburgh Review, the Yellow Dwarf and the London Magazine. In these journals Hazlitt produced a series of essays on art, drama, literature and politics. During this period he established himself as England's leading expert on the writings of William Shakespeare.

Hazlitt wrote several books on literature including Characters of Shakespeare (1817), A View of the English Stage (1818), English Poets (1818) and English Comic Writers (1819). In these books he urged the artist to be aware of his social and political responsibilities. Hazlitt continued to write about politics and his most important books on this subject is Political Essays with Sketches of Public Characters (1819). In the book Hazlitt explains how the admiration of power turns many writers into "intellectual pimps and hirelings of the press."

Hazlitt's marriage to Sarah ended in 1823 as a result of an affair with a maid, Sarah Walker. Hazlitt wrote an account of this relationship in his book Liber Amoris. In 1824 Hazlitt married Isabella Bridgewater but this relationship only lasted a year.

In The Spirit of the Age: Contemporary Portraits (1825) Hazlitt provides a series of contemporary portraits including Samuel Taylor Coleridge, William Wordsworth, Robert Southey, William Cobbett, William Godwin and William Wilberforce. This was followed by The Plain Speaker (1826) and Life of Napoleon (4 volumes, 1828-30).

William Hazlitt died in poverty of stomach cancer on 18th September 1830.

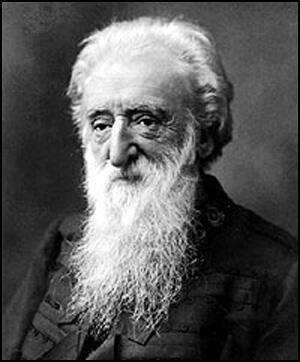

On this day in 1829 William Booth, son of a builder, was born in Nottingham in 1829. At the age of fifteen he was converted to Christianity and became a revivalist preacher. In 1849 he moved to London where he found work in a pawnbroker's shop at Walworth. Booth developed strong views on the role of church ministers believing they should be "loosing the chains of injustice, freeing the captive and oppressed, sharing food and home, clothing the naked, and carrying out family responsibilities."

In 1852 Booth met Catherine Mumford. Catherine shared William's commitment to social reform but disagreed with his views on women. On one occasion she objected to William describing women as the "weaker sex". William was also opposed to the idea of women preachers. When Catherine argued with William about this he added that although he would not stop Catherine from preaching he would "not like it". Despite their disagreements about the role of women in the church, the couple married on 16th June 1855, at Stockwell New Chapel.

It was not until 1860 that Catherine Booth first started to preach. One day in Gateshead Bethseda Chapel, a strange compulsion seized her and she felt she must rise and speak. Catherine's sermon was so impressive that William Booth changed his mind about women's preachers. Catherine soon developed a reputation as an outstanding speaker but many Christians were outraged by the idea. As Catherine pointed out at that time it was believed that a woman's place was in the home and "any respectable woman who raised her voice in public risked grave censure."

In 1865 William and Catherine founded the Whitechapel Christian Mission in London's East End to help feed and house the poor. The mission was reorganized in 1878 along military lines, with the preachers known as officers and Booth as the general. After this the group became known as the Salvation Army.

William Booth sought to bring into his worship services an informal atmosphere that would encourage new converts. Joyous singing, instrumental music, clapping of hands and an invitation to repent characterized Salvation Army meetings.

General Booth was deeply influenced by his wife Catherine Booth, who believed that women were equal to men and it was only inadequate education and social custom that made them men's intellectual inferiors. She was an inspiring speaker and helped to promote the idea of women preachers. The Salvation Army gave women equal responsibility with men for preaching and welfare work and on one occasion William Booth remarked that: "My best men are women!"

The Church of England were at first extremely hostile to Booth's activities. Lord Shaftesbury, a leading politician and evangelist, described William Booth as the "Anti-Christ". One of the main complaints against Booth was his "elevation of women to man's status". Members of the Salvation Army were imprisoned for open-air preaching and their support for the Temperance Society made them the target for gangs of men who became known as the Skeleton Army.

William andCatherine Booth were also active in the campaign to improving the working conditions of women working at the Bryant & May factory in the East End. Not only were these women only earning 1s. 4d. for a sixteen hour day, they were also risking their health when they dipped their match-heads in the yellow phosphorus supplied by manufacturers such as Bryant & May. A large number of these women suffered from 'Phossy Jaw' (necrosis of the bone) caused by the toxic fumes of the yellow phosphorus. The whole side of the face turned green and then black, discharging foul-smelling pus and finally death.

Booth pointed out that most other European countries produced matches tipped with harmless red phosphorus. Bryant & May responded that these matches were more expensive and that people would be unwilling to pay these higher prices.

In 1891 the Salvation Army opened its own match-factory in Old Ford, East London. Only using harmless red phosphorus, the workers were soon producing six million boxes a year. Whereas Bryant & May paid their workers just over twopence a gross, the Salvation Army paid their employees twice this amount.

William Booth organised conducted tours of MPs and journalists round this 'model' factory. He also took them to the homes of those "sweated workers" who were working eleven and twelve hours a day producing matches for companies like Bryant & May. The bad publicity that the company received forced the company to reconsider its actions. In 1901, Gilbert Bartholomew, managing director of Bryant & May, announced it had stopped used yellow phosphorus.

Gradually opinion on William Booth's activities changed. He was made a freeman of London, granted a honorary degree from Oxford University and in 1902 was invited to attend the coronation of Edward VII. When William Booth died in 1912, his eldest son, William Bramwell Booth, became the leader of the Salvation Army.

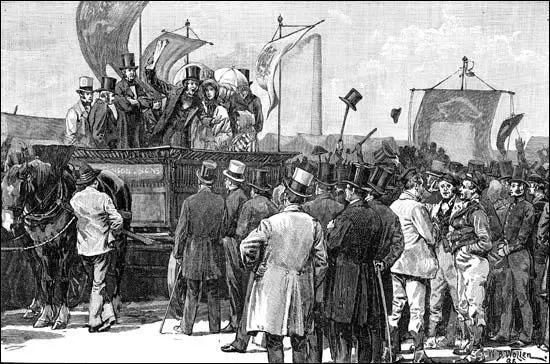

On this day in 1848, Chartist leader, Feargus O'Connor organized a mass Chartist meeting at Kennington Common. O'Connor decided on a new strategy that would combine several different tactics: a large public meeting, a procession and the presentation of a petition to the House of Commons.

O'Connor warned the prime minister, Lord John Russell, that after the speeches he intended to lead the large crowd to Parliament where he would present a petition to the government. Russell was in a awkward position because all his political life he had campaigned for freedom of speech and universal suffrage. However, since he became prime minister in 1846, he had been unable to persuade the majority of MPs in the House of Commons to agree to parliamentary reform. Afraid that the meeting would result in a riot, Russell decided to make sure that there would be 8,000 soldiers and 150,000 special constables on duty in London that day. In return for allowing the meeting to take place, Russell asked O'Connor not to take the crowd and the petition to Parliament.

The meeting took place without violence. Feargus O'Connor claimed that over 300,000 assembled at Kennington Common, but others argued that this figure was a vast exaggeration. The government said it was only 15,000 and The Times reporter estimated that it was probably about 20,000. The Sunday Observer, a newspaper fairly sympathetic to parliamentary reform, suggested that the true figure was around 50,000.

Feargus O'Connor also told the crowd that the petition contained 5,706,000 signatures. However, when examined by MPs it was only 1,975,496, and many of these were clear forgeries. O'Connor's many enemies in the parliamentary reform movement accused him of destroying the credibility of Chartism. His behaviour at Kennington Common did not help the reform movement and Chartism went into rapid decline after April 1848.

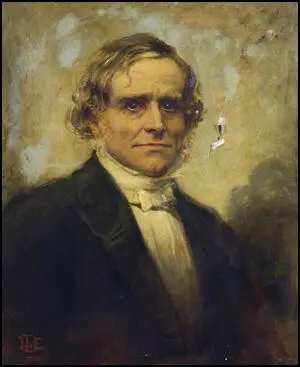

On this day in 1848, group of Christians who supported Chartism formed the Christian Socialist movement. People who attended the meeting included Frederick Denison Maurice, Charles Kingsley and Thomas Hughes. The meeting was a response to the decision by the House of Commons to reject the recent Chartist Petition. The men, who became known as Christian Socialists, discussed how the Church could help to prevent revolution by tackling what they considered were the reasonable grievances of the working class.

Frederick Denison Maurice was acknowledged as the leader of the group and his book The Kingdom of Christ (1838) became the theological basis of Christian Socialism. In the book Maurice argued that politics and religion are inseparable and that the church should be involved in addressing social questions. Maurice rejected individualism, with its competition and selfishness, and suggested a socialist alternative to the economic principles of laissez faire. Christian Socialists promoted the cooperative ideas of Robert Owen and suggested profit sharing as a way of improving the status of the working classes and as a means of producing a just, Christian society.

Maurice's biographer, Bernard Reardon, has argued: "In 1850 Maurice publicly accepted the designation Christian socialist for his movement.... He disliked competition as fundamentally unchristian, and wished to see it, at the social level, replaced by co-operation, as expressive of Christian brotherhood... Maurice held Bible classes and addressed meetings attended by working men who, although his words carried less of social and political guidance than moral edification, were invariably impressed by the speaker. But the actual means by which the competitiveness of the prevailing economic system was to be mitigated was judged to be the creation of co-operative societies."

The Christian Socialists published two journals, Politics of the People (1848-1849) and The Christian Socialist (1850-51). The group also produced a series of pamphlets under the title Tracts on Christian Socialism. Other initiatives included a night school in Little Ormond Yard and helping to form eight Working Men's Associations. In 1850 Thomas Hughes, Edward Neale, Lloyd Jones, and other members of the group helped to establish the London Cooperative Store.

Disagreements between members resulted in the Christian Socialists being inactive between 1854 and the late 1870s. The 1880s saw a revival of the movement and by the end of the century a variety of Christian Socialist groups had been formed including the Socialist Quaker Society, the Roman Catholic Socialist Society, the Guild of St. Matthew, and the Christian Social Union.

Christian Socialists also dominated the leadership of the Independent Labour Party formed in 1893. This included James Keir Hardie, Philip Snowden, Ben Tillett, Tom Mann, Katharine Glasier, Margaret McMillan and Rachel McMillan.

The Christian Socialist movement also influenced many of the leaders of the American Socialist Party such as Norman Thomas and Upton Sinclair.

On the outbreak of the First World War a large number of Christian Socialists joined the No-Conscription Fellowship (NCF), an organisation formed by Clifford Allen and Fenner Brockway, that encouraged men to refuse war service. The NCF required its members to "refuse from conscientious motives to bear arms because they consider human life to be sacred."

Wilfred Wellock, a Christian Socialist, joined the Independent Labour Party. "As I moved about the country after 1920 it was next to impossible to secure a response to any kind of spiritual appeal... The only organisation that appeared to be advancing was the Independent Labour Party... The rapid march of the socialist movement in Britain at this time, with the Independent Labour party as its spearhead, owed its success to its essentially spiritual appeal. The ILP inherited the spiritual idealism of the early Christian Socialists and of the artist-poet-craftmanship school of William Morris... This was the only kind of socialism that appealed to me... I am a socialist, provided you give a spiritual interpretation to the term... I have only recently decided to enter practical politics since I have seen the possibility of making politics, through the introduction of spiritual considerations, a veritable means of social transformation."

In 1921 Wellock published Christian Communism. He argued that is " our business is to create a Christian Communist consciousness, and to let the revolution, or what there be, come out of that... We must concentrate upon the ideal, preach and teach it everywhere, proclaim it in the cities, in the churches, at the street corners - go into the highways and the hedges and compel the people to see life anew, and in the light of a finer ideal to re-create the world."

There was a revival of Christian Socialism after the outbreak of the Second World War. The writer, John Middleton Murry, argued for "socialist-communities, prepared for hardship and practised in brotherhood, might be the nucleus of a new Christian Society, much as the monasteries were during the dark ages."

On this day in 1864 Mary Edwards Walker was captured by the Confederate Army. Mary was born in Oswego, New York, on 26th November, 1832. Determined to become a doctor, she graduated from Syracuse Medical College in 1855. She established a practice in Rome, New York, and married the physician, Albert Miller. The relationship was not successful and the couple separated in 1859.

Walker, a strong feminist, travelled to Washington on the outbreak of the American Civil War to offer her services to the Union Army. She worked as a volunteer nurse and was not sent to the front-line until September, 1863. Walker was appointed by General George Thomas as assistant surgeon in the Army of the Cumberland. The only woman doctor in the army, Walker served at Fredericksburg, Chickamauga and Atlanta.

Walker was captured by the Confederate Army and spent four months in a Richmond prison and was not released until 12th August, 1864. Released to tend the sick and wounded, Walker later claimed she used this opportunity to spy on the enemy. In 1865 she became the only woman in the American Civil War to win the Congressional Medal of Honor.

After the war Walker published two books, Hit (1871) and Unmasked (1878). She was also active in feminist organizations and was arrested several times for masquerading as a man. As well as campaigning for women's suffrage and for the Women's Christian Temperance Union, Walker gave lectures on the dangers of tobacco.

Mary Edwards Walker died in Oswego, on 21st February, 1919. In 1917 Walker had her Congressional Medal of Honor revoked. President Jimmy Carter reinstated the award in 1977.

On this day in 1880 sociologist and politician Frances Perkins, the daughter of Susan Bean Perkins and Frederick W. Perkins, the owner of a stationer's business, was born in Boston on 10th April, 1882. After graduating from Mount Holyoke College, she worked as a social worker in Worcester, Massachusetts, and a teacher in Chicago.

Perkins was deeply influenced by the writings of investigative journalists such as Lincoln Steffens, Ray Stannard Baker, Jacob A. Riis and Upton Sinclair. While in Chicago she became involved in Hull House, a settlement house founded by Jane Addams. Later she moved to Philadelphia, where she worked with immigrant girls. Perkins later explained that during this period attitudes changed towards poverty: "Proposals began to be made for laws to overcome social disadvantages. Societies and voluntary agencies, aiming to prevent abuses and promote remedies, sprang up. There was a sincere effort on the part of the American people to find the way of social justice. Shorter hours and better wages, removal of slums, new tenement house laws for sanitation, fire safety, and decency; reforms to prevent child labour, prevention of the use of hazardous chemicals in industry began to be mentioned in political speeches and legislation in some states. Foremost was the idea that poverty is preventable, that poverty is destructive, wasteful, demoralizing, and that poverty in the midst of potential plenty is morally unacceptable in a Christian and democratic society."

Perkins took a master's degree in political science at Columbia University in 1910 before becoming the executive secretary of the National Consumer's League (NCL). This work also brought her into contact with progressive politicians in New York City such as Robert Wagner and Alfred Smith. In 1919, Smith, the new governor of New York, appointed Perkins to the Industrial Board. She became chairman of the board in 1924 and while in this post she managed to obtain a reduction in the working week for women to 54 hours.

When Franklin D. Roosevelt became governor of New York in 1929, he appointed Perkins as his Industrial Commissioner. The former governor, Alfred Smith, warned against this as he argued that "men will take advice from a woman, but it is hard for them to take orders from a woman." Perkins recalled: "Roosevelt derived not only from intellectual convictions, but also from a new idealism and humanitarianism in which the economic and cultural aspirations of the common man were beginning to play a part in the political program. These concepts began to come alive in this country in the late nineties and early 1900s and found expression in literature, poetry, drama, and the graphic arts. The pity and terror of the slums, mills, and work shops, with their low wages and long hours, were used for artistic effect as in Greek tragedy."

In 1933 President Roosevelt selected Perkins as his Secretary of Labor. She therefore became the first woman in American history to hold a Cabinet post. As she revealed later, her first proposals included: "immediate federal aid to the states for direct unemployment relief, an extensive program of public works, a study and an approach to the establishment by federal law of minimum wages, maximum hours, true unemployment and old-age insurance, abolition of child labour, and the creation of a federal employment service." Although it was a very radical programme, Roosevelt accepted it with enthusiasm.

Hugh S. Johnson joined with Bernard Baruch and Alexander Sachs, an economist with Lehman Corporation, to draw up a proposal to help stimulate the economy. The central feature was the the provision for the legalization of business agreements (codes) on competitive and labour practices. Johnson believed that the nation's traditional commitment to laissez-faire was outdated. He argued that scientific and technological improvements had led to over-production and chronically unstable markets. This, in turn, led to more extreme methods of competition, such as sweatshops, child labour, falling prices and low wages.

Hugh S. Johnson pointed out that he had leant a lot from his experiences with the War Industries Board (WIB) He hoped that businessmen would cooperate out of enlightened self-interest, but discovered they had trouble looking beyond their own immediate profits. Despite appeals to patriotism, they had hoarded materials, charged exorbitant prices and given preference to civilian customers. Johnson explained that the WIB had dealt with these men during the First World War by threatening to commandeer their production or to deny them fuel and raw materials. These threats usually won co-operation from the owners of these companies.

Johnson therefore argued any successful scheme would need to inject an element of compulsion. He told Frances Perkins: "This is just like a war. We're in a war. We're in a war against depression and poverty and we've got to fight this war. We've got to come out of this war. You've got to do here what you do in a war. You've got to give authority and you've got to apply regulations and enforce them on everybody, no matter who they are or what they do.... The individual who has the power to apply and enforce these regulations is the President. There is nothing that the President can't do if he wishes to! The President's powers are unlimited. The President can do anything."

On 9th March 1933, President Franklin D. Roosevelt called a special session of Congress. He told the members that unemployment could only be solved "by direct recruiting by the Government itself." For the next three months, Roosevelt proposed, and Congress passed, a series of important bills that attempted to deal with the problem of unemployment. The special session of Congress became known as the Hundred Days and provided the basis for Roosevelt's New Deal.

Hugh S. Johnson became convinced that his plan should play a central role in encouraging industrial recovery. However, its original draft was rejected by Raymond Moley. He argued that the proposed bill would give the president dictatorial powers that Roosevelt did not want. Moley suggested he worked with Donald R. Richberg, a lawyer with good relationship with the trade union movement. Together they produced a new draft bill. Richberg argued that business codes would increase prices. If purchasing power did not rise correspondingly, the nation would remain mired in the the Great Depression. He therefore suggested that the industrial recovery legislation would need to include public works spending. Johnson became convinced of this argument and added that the promise of public spending could be used to persuade industries to agree to these codes.

President Franklin D. Roosevelt suggested that Johnson and Richberg should work with Senator Robert F. Wagner, who also had strong ideas on industrial recovery policy and other key figures in his administration, Frances Perkins, Guy Tugwell and John Dickinson. He told them to "shut themselves up in a room" until they could come up with a common proposal. According to Perkins it was Johnson's voice that dominated these meetings. When it was suggested that the Supreme Court might well rule the legislation as unconstitutional, Johnson argued: "Well, what difference does it make anyhow, because before they can get these cases to the Supreme Court we will have won the victory. The unemployment will be over and over so fast that nobody will care."

The draft legislation was finished on 14th May. It went before Congress and the National Industrial Recovery Act (NIRA) was passed by the Senate on 13th June by a vote of 46 to 37. The National Recovery Administration (NRA) was set up to enforce the NIRA. President Franklin D. Roosevelt named Hugh Johnson to head it. Roosevelt found Johnson's energy and enthusiasm irresistible and was impressed with his knowledge of industry and business.

Huey P. Long was totally opposed to the appointment. He argued that Hugh S. Johnson was nothing more than an employee of Bernard Baruch and would permit the most conservative elements in the Democratic Party to do as they pleased with American industry. Guy Tugwell also had his concerns about his relationship with Baruch: "It would have been better if he had been further from Baruch's special influence." He was concerned about other matters: "I think his tendency to be gruff in personal matters will be an handicap and his occasional drunken sprees will not help." However, overall he thought it was a good appointment: "Hugh is sincere, honest, believes in many social changes which seem to me right, and will do a good job." Surprisingly, Baruch himself had warned Frances Perkins against the appointment: "Hugh isn't fit to be head of the NRA. He's been my number-three man for years. I think he's a good number-three man, maybe a number-two man, but he's not a number-one man. He's dangerous and unstable. He gets nervous and sometimes goes away without notice. I'm fond of him, but do tell the President to be careful. Hugh needs a firm hand."

Some people argued that Johnson had pro-fascist tendencies. He gave Frances Perkins a copy of The Corporate State by Raffaello Viglione, a book stressed the achievements of Benito Mussolini. Johnson told Perkins that Mussolini was using measures that he would like to adopt. Perkins later claimed that Johnson was no fascist but was worried that comments like this would lead to his critics claiming that he "harbored fascist leanings."

Johnson told Perkins that he intended to draft a code for an industry simply by meeting with the representatives of its trade association. This would follow the pattern of the way the War Industries Board worked during the First World War. Perkins recognized that this approach could be justified in times of war but saw no compelling reason for them in 1933. She informed him that everything must be done in public hearings at which anyone, particularly representatives of labour and the public, could make objections or suggest modifications.

In 1933, Robert F. Wagner, chairman of the National Recovery Administration, introduced a bill to Congress to help protect trade unionists from their employers. With the support of Perkins, Wagner's proposals became the National Labor Relations Act. It established a three man National Labor Relations Board empowered to administer the regulation of labour relations in industries engaged in or affecting interstate commerce.

Frances Perkins was sceptical of the value of a 30-hour week unless it included provision for maintaining wages for those paid by the hour. So she suggested amendments to combine minimum wages with reduced hours. Although this was supported by the trade unions, it was opposed by the employers. Roosevelt eventually agreed to the establishment of the National Industrial Recovery Act (NIRA). This allowed industry to write its own codes of fair competition but at the same time provided special safeguards for labor. Section 7a of NIRA stipulated that workers should have the right to organize and bargain collectively through representatives of their own choosing and that no one should be banned from joining an independent union. The NIRA also stated that employers must comply with maximum hours, minimum pay and other conditions approved by the government.

Perkins was a strong advocate of government involvement in the economy and played an important role in many aspects of the New Deal including the Civilian Conservation Corps. She wrote: "In one of my conversations with the President in March 1933, he brought up the idea that became the Civilian Conservation Corps. Roosevelt loved trees and hated to see them cut and not replaced. It was natural for him to wish to put large numbers of the unemployed to repairing such devastation. His enthusiasm for this project, which was really all his own, led him to some exaggeration of what could be accomplished. He saw it big. He thought any man or boy would rejoice to leave the city and work in the woods. It was characteristic of him that he conceived the project, boldly rushed it through, and happily left it to others to worry about the details."

Some leading figures in the Roosevelt administration, including Perkins, Harold L. Ickes, Rex Tugwell, and Henry A. Wallace, became highly suspicious of Johnson's policies at the NRA. They believed that Johnson was permitting the larger industries "to get a stranglehold on the economy" and suspected that "these industries would use their power to raise prices, restrict production, and allocate capital and materials among themselves". They decided to closely monitor his actions.

On 27th August, the automobile manufacturers, except for Henry Ford, who believed the NIRA was a plot instigated by his competitors, agreed terms of a deal. Ford announced he intended to meet the wage and hour provision of the code or even to improve on them. However, he refused to sign up to the code. Johnson reacted by urging the public not to purchase Ford vehicles. He also told the federal government not to purchase vehicles from Ford dealers. Johnson commented: "If we weaken on this, it will greatly harm the Blue Eagle principle and campaign." Johnson's actions resulted in a decline in sales of Ford cars and trucks in 1933. However, it only had a short-term impact and in 1934 the company had increased sales and profits.

On 7th March, 1934, President Franklin D. Roosevelt created a National Recovery Review Board to study monopolistic tendencies in the codes. This was in response to criticism of the NRA by influential figures such as Gerald Nye, William Borah and Robert LaFollette. Johnson, in what he later said was "a moment of total aberration," agreed with Donald Richberg that Clarence Darrow should head the investigation. Johnson was furious when Darrow reported back that he "found that giant corporations dominated the NIRA code authorities and this was having a detrimental impact on small business". Darrow also signed a supplementary report which argued that recovery could only be achieved through the fullest use of productive capacity, which lay "in the planned use of America's resources following socialization".

Johnson was furious with the report and wrote to President Roosevelt that it was the most "superficial, intemperate and inaccurate document" he had ever seen. He added that Darrow had given the United States a choice between "Fascism and Communism, neither of which can be espoused by anyone who believes in our democratic institutions of self-government." Johnson advised Roosevelt that the National Recovery Review Board should be abolished immediately.

Hugh S. Johnson was also having financial problems. His $6,000-a-year salary did not meet his outgoings. Between October 1933 and September 1934 he borrowed $31,000 from Bernard Baruch, who told Perkins, "I like him. I'm fond of him. I'll always see that he has work to do and a salary coming in one way or another." Perkins took this opportunity to try and get rid of Johnson and asked Baruch "to say to Hugh that you need him badly and want him back.... tell him you need him and have a good post for him".

Baruch said this was impossible: "Hugh's got so swell headed now that he sometimes won't even talk to me on the telephone. I've called him up and tried to save him from two or three disasters that I've heard about. People have come to me because they knew that I knew him well, but sometimes he won't even talk to me. When he does talk to me, he doesn't say anything, or he isn't coherent... He's just pushing off. I never could manage him again. Hugh has got too big for his boots. He's got too big for me. I could never manage him again. My organization could never absorb him. He's learned publicity too, which he never knew before. He's tasted the tempting, but poisonous cup of publicity. It makes a difference. He never again can be just a plain fellow working in Baruch's organization. He's now the great General Hugh Johnson of the blue eagle. I can never put him in a place where I can use him again, so he's just utterly useless."

On 9th May 1934, the International Longshoremen's Association went on strike in order to obtain a thirty-hour week, union recognition and a wage increase. A federal mediating team, led by Edward McGrady, worked out a compromise. Joseph P. Ryan, president of the union, accepted it, but the rank and file, influenced by Harry Bridges, rejected it. In San Francisco the vehemently anti-union Industrial Association, an organization representing the city's leading industrial, banking, shipping, railroad and utility interests, decided to open the port by force. This resulted in considerable violence and on 13th July the San Francisco Central Labor Council voted for a general strike.

Hugh S. Johnson visited the city where he spoke to John Francis Neylan, chief counsel for the Hearst Corporation, and the most significant figure in the Industrial Association. Neylan convinced Johnson that the general strike was under the control of the American Communist Party and was a revolutionary attack against law and order. Johnson later wrote: "I did not know what a general strike looked like and I hope that you may never know. I soon learned and it gave me cold shivers."

On 17th July 1934 Johnson gave a speech to a crowd of 5,000 assembled at the University of California, where he called for the end of the strike: "You are living here under the stress of a general strike... and it is a threat to the community. It is a menace to government. It is civil war... When the means of food supply - milk to children, necessities of life to the whole people - are threatened, that is bloody insurrection... I am for organized labor and collective bargaining with all my heart and soul and I will support it with all the power at my command, but this ugly thing is a blow to the flag of our common country and it has to stop.... Insurrection against the common interest of the community is not a proper weapon and will not for one moment be tolerated by the American people who are one - whether they live in California, Oregon or the sunny South."

Johnson's speech inspired local right-wing groups to take action against the strikers. Union offices and meeting halls were raided, equipment and other property destroyed, and communists and socialists were beaten up. Johnson further inflamed the situation when he turned up for a meeting with John McLaughlin, the secretary of the San Francisco Teamsters Union, on 18th July, drunk. Instead of entering into negotiations, he made a passionate speech attacking trade unions. McLaughlin stormed out of the meeting and the strike continued.

The New Republic urged President Franklin D. Roosevelt to "crack down on Johnson" before he destroys the New Deal. Perkins was also furious with Johnson. In her opinion he had no right to become involved in the dispute and made it look like the government, in the form of the National Recovery Administration, was on the side of the employers. Demonstrations took place at NRA headquarters with protestors carrying placards claiming that it was biased against the trade union movement.

On 21st August 1934, the National Labor Relations Board ruled against Johnson and rebuked him for "unjustified interference" in union activity. Henry Morgenthau informed Roosevelt that in his opinion Johnson should be removed from the NRA. Rex Tugwell and Henry Wallace also told Roosevelt that Johnson should be sacked. Harry Hopkins, the head of the Federal Emergency Relief Administration and the Civil Works Administration, advised Roosevelt that 145 out of 150 of the highest officials in the government believed that Johnson's usefulness was at an end and that he should be retired.

Within the NRA many officials resented the power of Frances Robinson. One official reported to Adolf Berle that as many as half of the men in the agency were in danger of resigning "because of the affair between Johnson and Robby". He had also lost the confidence of many of his colleagues. Donald Richberg wrote in a memo dated 18th August 1934: "The General himself is, in the opinion of many, in the worst physical and mental condition and needs an immediate relief from responsibility."

President Franklin D. Roosevelt asked to see Hugh S. Johnson. He wrote in his autobiography that he knew he was going to be sacked when he saw his two main enemies in Roosevelt's office "when Mr. Richberg and Madam Secretary did not look up" I realised they had "been skinning a cow". Roosevelt asked him to go on a tour and make a report on European recovery. Sensing that this was "the sugary lipstick smeared over the kiss of death" he replied: "Mr. President, of course there is nothing for me to do but resign immediately." Roosevelt now backed down and said he did not want him to go.

Johnson believed that Donald Richberg was the main person behind the plot to get him removed. He wrote to Roosevelt on 24th August: "I was completely fooled by him (Richberg) until recently but may I suggest to you that if he would double-cross me, he would double-cross you.... I am leaving merely because I have a pride and a manhood to maintain which I can no longer sustain after the conference of this afternoon and I cannot regard the proposal you made to me as anything more than a banishment with futile flowers and nothing more insulting has ever been done to me than Miss Perkins' suggestion that, as a valedictory, I ought to get credit for the work I have done with NRA. Nobody can do that for me."

Hugh S. Johnson continued to make controversial attacks on those on the left. He accused Norman Thomas, the leader of the Socialist Party of America, of inspiring the United Textile Workers to carry out an illegal strike. The charge against Thomas was without foundation. It was also not an illegal strike and he was later forced to apologize for these inaccurate statements.

Johnson also made a speech on the future of the NRA. He said it needed to be scaled back. Johnson added that Louis Brandeis, a member of the Supreme Court, agreed with him: "During the whole intense experience I have been in constant touch with that old counselor, Judge Louis Brandeis. As you know, he thinks that anything that is too big is bound to be wrong. He thinks NRA is too big, and I agree with him." Brandeis quickly told Roosevelt that this was not true. It also implied that Brandeis had prejudged NRA even before the Supreme Court had ruled on the NRA's constitutionality.

President Franklin D. Roosevelt decided that Johnson must now resign. He was unable to do it himself and asked Bernard Baruch to do it for him. Baruch contacted Johnson and bluntly told him he must go. He later recalled that "Johnson kicked up a bit" but he made it clear that he had no choice. "When the Captain wants your resignation you better resign." On 24th September, 1934, Hugh S. Johnson submitted his resignation.

Three days later, Roosevelt appointed Richberg as Executive Director of the National Industrial Recovery Board, that had replaced the National Recovery Administration. Richberg had difficulty running this new organization. Arthur M. Schlesinger, the author of The Age of Roosevelt: The Coming of the New Deal (2003) has argued that "Richberg engaged in double-dealing, lying to the President about the views of his subordinates and agreeing to his staff's requests that he raise issues with the President and later refusing to do so."

On 27th May 1935 the Supreme Court declared the National Industrial Recovery Board as unconstitutional. The reasons given were that many codes were an illegal delegation of legislative authority and the federal government had invaded fields reserved to the individual states. Donald Richberg resigned on 16th June, 1935.

In June, 1938 Perkins managed to persuade Congress to pass the Fair Labor Standards Act. The main objective of the act was to eliminate "labor conditions detrimental to the maintenance of the minimum standards of living necessary for health, efficiency and well-being of workers". The act established maximum working hours of 44 a week for the first year, 42 for the second, and 40 thereafter. Minimum wages of 25 cents an hour were established for the first year, 30 cents for the second, and 40 cents over a period of the next six years. The act also prohibited child labour in all industries engaged in producing goods in inter-state commerce and placed a limitation of the labor of boys and girls between 16 and 18 years of age in hazardous occupations.

Perkins remained as Secretary of Labor until the death of Franklin D. Roosevelt in 1945. Her book, The Roosevelt I Knew, was published in 1946. President Harry Truman, appointed her to the United States Civil Service Commission. After leaving office in 1953 she taught at Cornell University.

Frances Perkins died in New York on 14th May 1965.

On this day in 1910 Paul Sweezy, the son of a vice president of the First National Bank of New York, was born. He was educated at Philips Exeter Academy and Harvard University, where he edited the journal, Crimson. In 1932 he went to the London School of Economics where he came under the influence of Harold Laski.

Sweezy returned to the United States as a Marxist and began work on The Theory of Capitalist Development. This was eventually published in 1942. He became active in politics and in 1948 was a supporter of Henry Wallace and the Progressive Party.

In 1949 Sweezy and Leo Huberman established the radical journal, The Monthly Review. Contributors included Albert Einstein, W. E. B. DuBois, Jean-Paul Sartre, Fidel Castro, Che Guevara, Malcolm X, G. D. H. Cole, E. P. Thompson, and Ralph Milliband.

Sweezy was a victim of McCarthyism. In 1954 he received a jail sentence after refusing to hand over notes for a lecture he had given at the University of New Hampshire.

In 1960 Sweezy and Huberman travelled to Cuba where they studied Castro's reforms in education, nationalisation of industry and land reform. In a special issue of The Monthly Review (Cuba: Anatomy Of A Revolution) Sweeezy and Huberman argued that Cuba was undergoing a socialist revolution.

Sweezy was co-author with Paul A. Baran of Monopoly Capital (1965). In the 1970s Sweezy became increasingly concerned with environmental issues and the undeveloped world. In 1971 he wrote "the principal (capitalist) contradiction... is not within the developed part but between the developed and undeveloped parts".

Paul Sweezy died on 27th February, 2004.

Julia O'Sullivan was born in Limehouse on 17th February 1873. Her father was John O'Sullivan, an immigrant from Cork. Julia married John Scurr in Woolwich in 1899. The couple had two sons and a daughter. At the time her husband was an active member of the Social Democratic Federation, and was associated with people such as H. M. Hyndman, Tom Mann, John Burns, Eleanor Marx, George Lansbury, Edward Aveling, H. H. Champion, Helen Taylor, Guy Aldred, John Spargo and Ben Tillet.

In 1905 Julia joined forces with James Keir Hardie, Dora Montefiore, George Lansbury to organise a deputation on unemployment of 1,000 women to meet the Prime Minister, Arthur Balfour. During this period she also became active in the struggle for women's suffrage and worked very closely with Sylvia Pankhurst.

In 1907 Julia Scurr became a member of to the Board of Guardians that ran the Poplar Workhouse. Working closely with George Lansbury she presented a report criticizing the lack of Day Rooms and recreational space at the Bow Infirmary.

In 1913, Sylvia Pankhurst, with the help of Julia Scurr, Millie Lansbury, Keir Hardie and George Lansbury, established the East London Federation of Suffragettes (ELF). An organisation that combined socialism with a demand for women's suffrage it worked closely with the Independent Labour Party. As June Hannam has pointed out: "The ELF was successful in gaining support from working women and also from dock workers. The ELF organized suffrage demonstrations and its members carried out acts of militancy. Between February 1913 and August 1914 Sylvia was arrested eight times.... She also drew on East End traditions by calling for rent strikes to support the demand for the vote."

On 6th February 1914 a group of supporters of women's suffrage, who were disillusioned by the lack of success of the National Union of Women's Suffrage Societies and disapproval of the arson campaign of the Women Social & Political Union, decided to form the United Suffragists movement. Membership was open to both men and women, militants and non-militants. Members included Julia Scurr, Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence, Frederick Pethick-Lawrence, Evelyn Sharp, Henry Nevinson, Margaret Nevinson, Hertha Ayrton, Israel Zangwill, Edith Zangwill, Lena Ashwell, Louisa Garrett Anderson, Eveline Haverfield, Maud Arncliffe Sennett, John Scurr and Laurence Housman.

Julia Scurr led a deputation of East End women to see Prime Minister Henry Asquith in June 1914 to protest about the low wages being paid to women. She told him: "Any rise in the price of rents, foods and other household commodities affects us women vitally... The position of working-class women is one that we all feel deeply. Our husbands die on the average at a much earlier age than do the men of other classes. Modern industrialism kills them off rapidly both by accident and by overwork... we are left often with a family of young children to support... The Poor Law has treated us mercilessly. It is hated by every poor woman. In many cases outdoor relief is altogether denied to the widow, as it is to the deserted wife, and only the Workhouse is offered, which means separation from the children."

In November 1919 Julia Scurr was elected to Poplar Council. The Labour Party had won 39 of the 42 council seats. In 1921 Poplar had a rateable value of £4m and 86,500 unemployed to support. Whereas other more prosperous councils could call on a rateable value of £15 to support only 4,800 jobless. George Lansbury proposed that the Council stop collecting the rates for outside, cross-London bodies. This was agreed and on 31st March 1921, Poplar Council set a rate of 4s 4d instead of 6s 10d. On 29th the Councillors were summoned to Court. They were told that they had to pay the rates or go to prison. At one meeting Millie Lansbury said: "I wish the Government joy in its efforts to get this money from the people of Poplar. Poplar will pay its share of London's rates when Westminster, Kensington, and the City do the same."

On 28th August over 4,000 people held a demonstration at Tower Hill. The banner at the front of the march declared that "Popular Borough Councillors are still determined to go to prison to secure equalisation of rates for the poor Boroughs." The Councillors were arrested on 1st September. Five women Councillors, including Julia, Millie Lansbury and Susan Lawrence, were sent to Holloway Prison. Twenty-five men, including George Lansbury and John Scurr, went to Brixton Prison. On 21st September, public pressure led the government to release Nellie Cressall, who was six months pregnant. Julia Scurr reported that the "food was unfit for any human being... fish was given on Friday, they told us, that it was uneatable, in fact, it was in an advanced state of decomposition".

Instead of acting as a deterrent to other minded councils, several Metropolitan Borough Councils announced their attention to follow Poplar's example. The government led by Stanley Baldwin and the London County Council was forced to back down and on 12th October, the Councillors were set free. The Councillors issued a statement that said: "We leave prison as free men and women, pledged only to attend a conference with all parties concerned in the dispute with us about rates... We feel our imprisonment has been well worth while, and none of us would have done otherwise than we did. We have forced public attention on the question of London rates, and have materially assisted in forcing the Government to call Parliament to deal with unemployment."

In the 1923 General Election, John Scurr, Susan Lawrence and George Lansbury were all elected to the House of Commons.The Labour Party won 191 seats. Although the Conservative Party had 258 seats, Herbert Asquith announced that the Liberal Party would not keep the Tories in office. If a Labour Government were ever to be tried in Britain, he declared, "it could hardly be tried under safer conditions".

On 22nd January, 1924 Stanley Baldwin resigned. At midday, Ramsay MacDonald went to Buckingham Palace to be appointed prime minister. MacDonald had not been fully supportive of the Poplar Councillors since he thought that "public doles, Popularism, strikes for increased wages, limitation of output, not only are not Socialism but may mislead the spirit and policy of the Socialist movement." George Lansbury was therefore not offered a post in his Cabinet.

John Wheatley, the new Minister of Health, had been a supporter of the Poplar Councillors. Edgar Lansbury wrote in The New Leader that he was sure that Wheatley would "understand and sympathise with them in this horrible problem of poverty, misery and distress which faces them." Lansbury's assessment was correct and as Janine Booth, the author of Guilty and Proud of It! Poplar's Rebel Councillors and Guardians 1919-25 (2009), has pointed out: "Wheatley agreed to rescind the Poplar order. It was a massive victory for Poplar, whose guardians had lived with the threat of legal action for two years and were finally vindicated."

Julia Scurr died on 10th April 1927 at the age of 57. George Lansbury wrote that he had no doubt that the period of imprisonment, and the treatment she received, was directly responsible for her death.

On this day in 1951 Hugh Gaitskell makes £30 million cuts to the NHS budget. Clement Attlee promoted Gaitskell to minister for economic affairs in November 1951. When Richard Stafford Cripps resigned nine months later, Gaitskell was appointed to succeed him as chancellor of the exchequer. Herbert Morrison approved of the appointment: "I regarded him at that time as a man of considerable ability and with a praiseworthy desire to act in a sane and responsible manner." Aneurin Bevan disagreed and sent a letter commenting: "I feel bound to tell you that for my part I think the appointment of Gaitskell to be a great mistake. I should have thought myself that it was essential to find out whether the holder of this great office would commend himself to the main elements and currents of opinion in the Party. After all, the policies which he will have to propound and carry out are bound to have the most profound and important repercussions throughout the movement."

One of his first tasks was to balance the budget. The National Insurance Act created the structure of the Welfare State and after the passing of the National Health Service Act in 1948, people in Britain were provided with free diagnosis and treatment of illness, at home or in hospital, as well as dental and ophthalmic services. Michael Foot, the author of Aneurin Bevan (1973): "On the afternoon of 10th April he (Hugh Gaitskell) presented his Budget, including the proposal to save £13 million - £30 million in a full year-by imposing charges on spectacles and on dentures supplied under the Health Service. And glancing over his shoulder at the benches behind him he had seemed to underline his resolve: having made up his mind, he said, a Chancellor 'should stick to it and not be moved by pressure of any kind, however insidious or well-intentioned'. Bevan did not take his accustomed seat on the Treasury bench, but listened to this part of the speech from behind the Speaker's chair, with Jennie Bevan by his side. A muffled cry of 'shame' from her was the only hostile demonstration Gaitskell received that afternoon." The following day, three members of the government, Harold Wilson, Aneurin Bevan and John Freeman resigned.

Harold Wilson argued that Gaitskell took this action as part of a battle he was having with Aneurin Bevan: "He was certainly ambitious, and had close links with the right-wing trade unions. It was not long before that ambition took the form of a determination to outmanoeuvre, indeed humiliate, Aneurin Bevan. Hugh, for his part, despised what he regarded as emotional oratory, and if he could defeat Nye in open conflict, he would be in a strong position to oust Morrison as the heir apparent to Clement Attlee. At the same time he would ensure that post-war socialism would take a less dogmatic form, totally anti-communist but unemotional."

attacking Herbert Morrison, Clement Attlee and Hugh Gaitskell (July, 1951)

On this day in 1975 Walker Evans died in New Haven, Connecticut. Walker Evans, the son of a successful advertising executive, was born in St. Louis, Missouri, on 3rd November, 1903. Educated at Phillips Academy and Williams College, he moved to Paris where he hoped to establish himself as a writer.

Evans returned to the United States and now attempted to making a living as a photographer. During the early years of his career he supported himself with a variety of different job. Some of Evans' photographs were accepted by the avant garde magazine, Hound and Horn. This led to him being commissioned to provide the pictures for Hart Crane's The Bridge (1930) and Carleton Beals' The Crime of Cuba (1932).

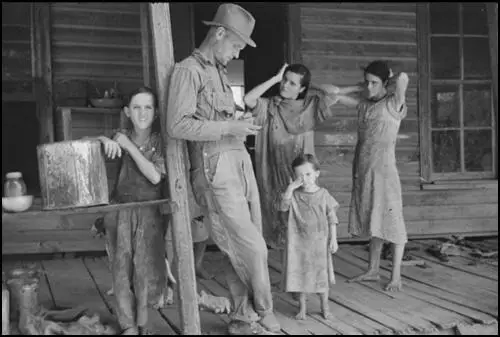

In 1935 Evans was invited by Roy Stryker to join the the federally sponsored Farm Security Administration. This small group of photographers, including Esther Bubley, Marjory Collins, Mary Post Wolcott, Arthur Rothstein, Russell Lee, Gordon Parks, Charlotte Brooks, Jack Delano, John Vachon, Carl Mydans, Dorothea Lange and Ben Shahn, were employed to publicize the conditions of the rural poor in America. During this period Evans established himself as one of America's leading documentary photographers.

Evans was honored with an exhibition in New York City's Museum of Modern Art. He also worked with the journalist, James Agee, on a study of Alabama sharecroppers. Although commissed by a magazine, the material was rejected and published in the book, Let Us Now Praise Famous Men (1941).

After the Second World War Walker was associate editor of Fortune Magazine (1945-65) and taught at Yale University (1965-75).