On this day on 6th February

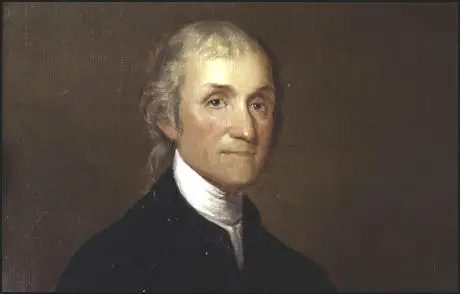

On this day 1804 Joseph Priestley died. Priestley, the son of a cloth-dresser from Leeds, was born in 1733. After the death of his mother in 1740, Joseph lived with his aunt, a person with strong nonconformist religious views. Priestley went to the local grammar school but after three years ill-health forced him to return home. Joseph was a brilliant student and with the help of local teachers, Joseph became proficient in physics, philosophy, algebra, mathematics and several different languages.

After his health improved, Joseph Priestley entered the new nonconformist Daventry Academy in Northamptonshire, where he studied history, science and philosophy. At Daventry he read David Hartley's Observations of Man (1749). Priestley was deeply influenced by Hartley's views on free will and the notion of human perfectibility through good education.

In 1755 Joseph Priestley became a minister at the Presbyterian church at Needham Market. Three years later he moved to Nantwich in Cheshire. Priestley also opened a small school where he developed his ideas on education. He was especially interested in exploring how science could improve the quality of human life. In 1761 Priestley was appointed as tutor at the dissenting Warrington Academy in Lancashire.

While at Warrington Joseph Priestley wrote Liberal Education for Civil and Active Life (1765). In the book he stressed the importance of science, arts, modern languages and history and argued they were better suited than the classics for those students who wanted a career in industry and commerce. This was followed by a book on science The History and Present State of Electricity (1767). In the book Priestley put forward the theory that the history of science was important because it showed how human intelligence discovers and directs the forces of nature, as well as illustrating the general progress of mankind.

Joseph Priestley now turned his attention to politics. In 1768 his book The First Principles of Government and the Nature of Political, Civil and Religious Liberty was published. In the book he argued for the development of a political system that maximizes civil liberty. In a statement that was to have an influence on the work of Jeremy Bentham and his ideas on Unitarianism, Priestley wrote: "The good and happiness of the members, that is the majority of the members of the state, is the great standard by which every thing relating to that state must finally be determined."

These three books brought Priestley to the attention of Richard Price and Benjamin Franklin. Both men became friendly with Priestley and encouraged his work in science and politics. After long discussions with the two men, Priestley wrote The State of Public Liberty in General and of American Affairs in Particular (1774). The pamphlet attacked the British government for depriving the colonists their rights and liberties.

Priestley's political beliefs made him unpopular with the British government. Church leaders were also concerned with the religious views expressed by Priestley in books such as The History of the Corruptions of Christianity (1782) and History of Early Opinions Concerning Jesus Christ (1786). The books developed Priestley's ideas on Unitarianism. They also included attacks on such doctrines as the virgin birth and the Holy Trinity. Many people, including King George III, became convinced that Priestley was now an atheist.

Priestley moved to Birmingham where he became friends with businessmen and scientists such as John Wilkinson, Josiah Wedgwood, Matthew Boulton and James Watt. Whereas Priestley's scientific work, for example, his discovery of oxygen, was welcomed, his religious and political views were constantly getting him into trouble. Priestley and his friend Richard Price became leaders of a group of men that became known as the Rational Dissenters. To the government, these were dangerous men.

Hostility towards Joseph Priestley increased in 1791 when he wrote a pamphlet defending the French Revolution. Priestley argued that he believed the events in France increased the chance of "universal peace and goodwill among all nations" as it made possible an "empire of reason". His predictions that the French Revolution heralded a change in the role of the monarchy upset King George III. The king and his supporters particularly disliked Priestley's view that in future monarchs will be the "first servants of the people and accountable to them". Priestley now obtained the nickname 'Gunpowder' after he expressed the view that it should be placed "under the old building of error and superstition".

In 1791 Priestley published A Political Dialogue on the General Principles of Government. In the book Priestley expressed similar political ideas to those expressed by Tom Paine in the Rights of Man. Later that year Priestley took part in forming a Constitutional Society in Birmingham. Tories in the city made inflammatory speeches attacking Priestley's political ideas and this resulted in a mob breaking into his house and destroying most of his papers, books and scientific equipment.

After the Birmingham riots Joseph Priestley moved to London where he taught history and science at New College, Hackney. Priestley experienced a great deal of hostility in London for his political and religious beliefs and in 1774 he decided to emigrate to America. He settled in Pennsylvania and over the next few years he wrote several books on Unitarianism. Priestley also established the first Unitarian Church in America.

On this day in 1816 John Castle agrees to be an agent provocateur. Castle was born in Yorkshire in about 1785. Castle moved to London where he found work in a brothel run by Mother Thoms in King Street Soho. In 1812 Castle and his friend, Daniel Davis, were arrested for forging bank notes. The charges against Castle were dropped when he agreed to give evidence against Davis. As a result of Castle's evidence in court, Daniel Davies was executed.

In 1816 Castle was working as a whitesmith when he met James Watson, one of the leaders of the Spencean Philanthropists, a group inspired by the ideas of Thomas Spence. Soon afterwards John Castle became a member of the Spenceans.

William Salmon, a police officer at Bow Street, knew of Castle's police record and when discovered that he had become a Spencean he told John Stafford, the Chief Clerk at Bow Street, and Home Office spymaster. Stafford decided to recruit Castle as a spy. After a combination of threats and promises, Castle agreed to provide Stafford information on the activities of the Spenceans.

On 2nd December 1816, the Spencean group organised a mass meeting at Spa Fields, Islington. The speakers at the meeting included Henry 'Orator' Hunt and James Watson. The magistrates decided to disperse the meeting and while Stafford and eighty police officers were doing this, one of the men, Joseph Rhodes was stabbed. The four leaders of the Spenceans, James Watson, Arthur Thistlewood, Thomas Preston and John Hopper were arrested and charged with high treason.

James Watson was the first to be tried. John Castle was the main prosecution witness. However, the defence council was able to show that Castle had a long criminal record and that his testimony was unreliable. The jury concluded that Castle was an agent provocateur (a person employed to incite suspected people to some open action that will make them liable to punishment) and refused to convict Watson. As the case against Watson had failed, it was decided to release the other three men who were due to be tried for the same offence.

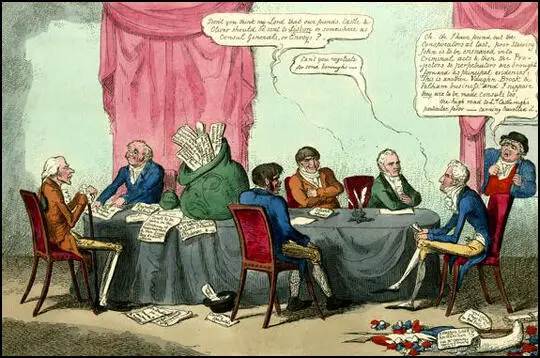

William Oliver, George Canning and Lord Castlereagh. In the picture spies (Reynolds, Castle

and Oliver) are providing government ministers with information on those

advocating parliamentary reform. (July 1817)

On this day in 1878 Hilda Mary Dallas was born in Japan. Her father Charles Dallas was teaching English to Japanese students. In 1901 she became a student at the Slade School of Art. Hilda who was described as ‘a handsome fair-haired girl' became the Women Social & Political Union (WSPU) organizer for South St Pancras.

In 1909 she joined forces with Alfred Pearse and Laurence Housman to form the Suffrage Atelier (an artists' collective campaigning for women's suffrage). The WSPU established its own newspaper, Votes for Women in October 1907. Its first editors were the husband and wife team of Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence and Frederick Pethick-Lawrence. The newspaper was printed by the St. Clement's Press. It was originally a monthly but after April 1908 it was published every week. At this time sales reached 5,000 copies a month.

In 1907 some leading members of the WSPU began to question the leadership of Emmeline Pankhurst and Christabel Pankhurst. These women objected to the way that the Pankhursts were making decisions without consulting members. In a conference in September 1907, Emmeline Pankhurst told members that she intended to run the WSPU without interference.

As a result of this speech, Charlotte Despard, Teresa Billington-Greig, Elizabeth How-Martyn, Dora Marsden, Helena Normanton, Anne Cobden Sanderson, Margaret Nevinson and seventy other members of the WSPU left to form the Women's Freedom League (WFL). Dallas remained close to people in the WFL but remained a member of the WSPU.

Hilda Dallas produced two posters to promote the Votes for Women. Permanent pitches were established in major cities to sell the newspaper. The Suffragette Bus, that toured the streets of London, also advertised the paper. By 1910 the circulation of the newspaper had increased to 30,000 a week. The newspaper was funded by the Pethick-Lawrences and all attempts to make a profit from the venture was abandoned in May, 1908 when it was decided to reduce the price from 3d to 1d.

At a meeting in France, in October 1912, Christabel Pankhurst told Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence and Frederick Pethick-Lawrence about the proposed arson campaign. When Emmeline and Frederick objected, Christabel arranged for them to be expelled from the the organisation. Emmeline later recalled in her autobiography, My Part in a Changing World (1938): "My husband and I were not prepared to accept this decision as final. We felt that Christabel, who had lived for so many years with us in closest intimacy, could not be party to it. But when we met again to go further into the question… Christabel made it quite clear that she had no further use for us."

As a result of this expulsion, the WSPU lost control of Votes for Women. They now published their own newspaper, The Suffragette. Dallas produced a poster for the newspaper. Initially, the circulation of the newspaper was about 17,000. The Home Office tried to suppress the newspaper. On 2nd May 1913 Sidney Granville Drew, the managing director of Victoria House Printing Company which printed the newspaper, was arrested.

The British government declared war on Germany on 4th August 1914. Two days later, Millicent Fawcett, the leader of the NUWSS declared that the organization was suspending all political activity until the conflict was over. Fawcett supported the war effort but she refused to become involved in persuading young men to join the armed forces. This WSPU took a different view to the war. It was a spent force with very few active members. According to Martin Pugh, the WSPU were aware "that their campaign had been no more successful in winning the vote than that of the non-militants whom they so freely derided".

The WSPU carried out secret negotiations with the government and on the 10th August the government announced it was releasing all suffragettes from prison. In return, the WSPU agreed to end their militant activities and help the war effort. Christabel Pankhurst, arrived back in England after living in exile in Paris. She told the press: "I feel that my duty lies in England now, and I have come back. The British citizenship for which we suffragettes have been fighting is now in jeopardy."

After receiving a £2,000 grant from the government, the WSPU organised a demonstration in London. Members carried banners with slogans such as "We Demand the Right to Serve", "For Men Must Fight and Women Must Work" and "Let None Be Kaiser's Cat's Paws". At the meeting, attended by 30,000 people, Emmeline Pankhurst called on trade unions to let women work in those industries traditionally dominated by men. She told the audience: "What would be the good of a vote without a country to vote in!".

Hilda Mary Dallas did not agree with this approach to the First World War and as a result she left the WSPU. She became a pacifist and produced and designed set & costumes for the 1929 Court Theatre production of the anti-war satirical play The Rumour that had been written by C. K. Munro. Hilda Dallas died in 1958.

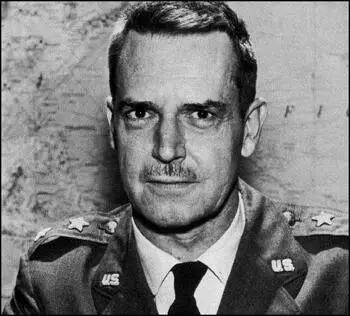

On this day in 1908 important CIA agent, Edward Lansdale was born in Detroit, Michigan. During the Second World War Lansdale was a member of the Office of Strategic Services (OSS), an organization that was given the responsible for espionage and for helping the resistance movement in Europe.

According to Sterling Seagrave, Lansdale was sent by General Charles Willoughby to the Philippines after the war. Lansdale "joined the torture sessions of Major Kojima Kashii "as an observer and participant". As Seagrave explains: "Since Yamashita had arrived from Manchuria in October 1944 to take over the defense of the Philippines, Kojima had driven him everywhere."

In charge of Kojima’s torture was an intelligence officer named Severino Garcia Diaz Santa Romana (Santy). He wanted Major Kojima to reveal each place to which he had taken General Tomoyuki Yamashita, where bullion and other treasure were hidden." Ray Cline argues that between 1945 and 1947 the gold bullion recovered by Santy and Lansdale was moved by ship to 176 accounts at banks in 42 countries. Robert Anderson and CIA agent Paul Helliwell set up these black gold accounts "providing money for political action funds throughout the noncommunist world."

Promoted to the rank of major Lansdale was appointed Chief of the Intelligence Division in the Philippines. His main task was to rebuild the country's security services.

On his return to the United States in 1948 Lansdale became a lecturer at the Strategic Intelligence School in Colorado. However, in 1950, Elpidio Quirino, the president of the Philippines, requested Lansdale's help in his fight against the communist insurrection taking place in his country.

In the early 1950s, Allen Dulles gave Lansdale $5-million to finance CIA operations against the Hukbalahap movement, the rural peasant farmers fighting for land-reform in the Philippines.

According to Sterling Seagrave Lansdale "was in and out of Tokyo on secret missions with a hand-picked team of Filipino assassins, assassinating leftists, liberals and progressives." CIA Director William Colby later commented: "Lansdale helped and perhaps created the best president the Philippines ever had...turned American policy away from support of French colonial rule in Vietnam to support of a non-Communist nationalist leader...he preached for Americans to support those willing to fight for themselves... He was one of the greatest spies in history... the stuff of legends."

In 1953 Lansdale was sent to Vietnam to advise the French in their struggle with the Vietminh. Dulles told President Dwight Eisenhower that he was sending one of his “best men”. The following year Lansdale and a team of twelve intelligence agents were sent to Saigon. The plan was to mount a propaganda campaign to persuade the Vietnamese people in the south not to vote for the communists in the forthcoming elections.

In the months that followed they distributed targeted documents that claimed the Vietminh and Chinese communists had entered South Vietnam and were killing innocent civilians. The Ho Chi Minh government was also accused of slaying thousands of political opponents in North Vietnam.

Colonel Lansdale also recruited mercenaries from the Philippines to carry out acts of sabotage in North Vietnam. This was unsuccessful and most of the mercenaries were arrested and put on trial in Hanoi. Finally, Lansdale set about training the South Vietnamese army (ARVN) in modem fighting methods. For it was coming clear that it was only a matter of time before the communists would resort to open warfare.

In 1955 Graham Greene published The Quiet American. The novel is set in Vietnam and involves the relationship between Thomas Fowler and Alden Pyle. Fowler is a veteran British journalist in his fifties, who has been covering the war in Vietnam for over two years. Pyle, the “Quiet American” of the title, is officially an aid worker, but is really employed by the CIA. It is believed that the Pyle character is partly based on that of Edward Lansdale.

Greene had worked for the British Secret Service during the Second World War. Although a fairly successful novelist at the time, Greene was also employed by The Times and Le Figaro as a journalist. Between 1951 to 1954 spent a long period of time in Saigon. In 1953 Lansdale became a CIA advisor on special counter-guerrilla operations to French forces against the Viet Minh.

While it is true that Graham Greene admitted that he never had the "misfortune to meet" Lansdale, the two men did know a lot about each other. Lansdale recalls that in 1954 he had dinner with Peg and Tilman Durdin at the Continental Hotel in Saigon. Greene was also there having a meal with several French officers. Lansdale claims that after he and the Durdins were leaving, Greene said something in French to his companions and the men began booing him.

Lansdale definitely thought that Pyle was based on him. He told Cecil B. Currey on 15th February, 1984: "Pyle was close to Trinh Minh Thé, the guerrilla leader, and also had a dog that went with him everywhere - and I was the only American close to Trinh Minh Thé and my poodle Pierre went everything with me."

In the book Pyle is sent to Vietnam by his government, ostensibly as a member of the American Economic Mission, but that assignment was only a cover for his real role as a CIA agent. According to one critic "Pyle was the embodiment of well-meaning American-style politics, and he blundered through the intrigue, treachery, and confusion of Vietnamese politics, leaving a trail of blood and suffering behind him." As Fowler points out in the novel, Pyle was attempting to "win the East for Democracy". However, according to Fowler, what the people of Vietnam really wanted was "enough rice" to eat. What is more: "They don't want to be shot at. They want one day to be much the same as another. They don't want our white skins around telling them what they want."

When the book was published in the United States in 1956 it was condemned as anti-American. Pyle (Lansdale) is portrayed as someone whose belief in the justice of American foreign policy allows him to ignore the appalling consequences of his actions. It was criticized by The New Yorker for portraying Americans as murderers.

The director, producer and screenwriter, Joseph L. Mankiewicz was chosen to make the film of The Quiet American. He visited Saigon in 1956 and was introduced to Edward Lansdale, whose cover was working at the International Rescue Committee’s office. The most controversial scene in the book is the bombing of a Saigon square in 1952 by a Vietnamese associate of Lansdale’s, General Trinh Minh Thé. In the novel, Greene suggests that Pyle/Lansdale, was behind the bombing. Lansdale suggested to Mankiewicz that the film should show that the bombing was “actually having been a Communist action”.

When he returned home Mankiewicz wrote to John O’Daniel, the chairman of the American Friends of Vietnam that he intended to completely change the anti-American attitude of Greene’s book. This included the casting of Second World War hero, Audie Murphy, as Alden Pyle.

In a letter that Edward Lansdale wrote to Ngo Dinh Diem he praised Mankiewicz’s treatment of the story as “an excellent change from Mr. Greene’s novel of despair” and “that it will help win more friends for you and Vietnam in many places in the world where it is shown."

As Hugh Wilford pointed out: “It was a brilliantly devious maneuver of postmodern literary complexity: by helping to rewrite a story featuring a character reputedly based on himself, Lansdale had transformed an anti-American tract into a cinematic apology for U.S. policy - and his own actions-in Vietnam.”

Graham Greene was furious with Mankiewicz’s treatment ofhis novel. "Far was it from my mind, when I wrote The Quiet American that the book would become a source of spiritual profit to one of the most corrupt governments in Southeast Asia."

In October, 1955, the South Vietnamese people were asked to choose between Bo Dai, the former Emperor of Vietnam, and Ngo Dinh Diem for the leadership of the country. Lansdale suggested that Diem should provide two ballot papers, red for Diem and green for Bao Dai. Lansdale hoped that the Vietnamese belief that red signified good luck whilst green indicated bad fortune, would help influence the result.

When the voters arrived at the polling stations they found Diem's supporters in attendance. One voter complained afterwards: "They told us to put the red ballot into envelopes and to throw the green ones into the wastebasket. A few people, faithful to Bao Dai, disobeyed. As soon as they left, the agents went after them, and roughed them up... They beat one of my relatives to pulp."

After the election Ngo Dinh Diem informed his American advisers that he had achieved 98.2 per cent of the vote. Lansdale warned him that these figures would not be believed and suggested that he published a figure of around 70 per cent. Diem refused and as the Americans predicted, the election undermined his authority.

Another task of Lansdale and his team was to promote the success of the rule of President Ngo Dinh Diem. Figures were produced that indicated that South Vietnam was undergoing an economic miracle. With the employment of $250 millions of aid per year from the United States and the clever manipulating of statistics, it was reported that economic production had increased dramatically.

Lansdale left Vietnam in 1957 and officially went to work for the Secretary of Defence in Washington. However, he was also employed as a senior officer in the Central Intelligence Agency. Posts held included: Deputy Assistant Secretary for Special Operations (1957-59), Staff Member of the President's Committee on Military Assistance (1959-61).

In March 1960, President Dwight Eisenhower of the United States approved a CIA plan to overthrow Fidel Castro. The plan involved a budget of $13 million to train "a paramilitary force outside Cuba for guerrilla action."

When President John F. Kennedy took office, Lansdale was appointed as Assistant Secretary of Defence for Special Operations. He argued that the CIA should work closely with exiles in Cuba, particularly those with middle-class professions, who had opposed Fulgencio Batista and had then become disillusioned with Fidel Castro because of his betrayal of the democratic process. Lansdale was also opposed to the Bay of Pigs operation because he knew that it would not trigger a popular uprising against Castro. Kennedy respected the advice of Lansdale and selected him to become project leader of Operation Mongoose.

Over 400 CIA officers were employed full-time on this project. Sidney Gottlieb of the CIA Technical Services Division was asked to come up with proposals that would undermine Castro's popularity with the Cuban people. Plans included a scheme to spray a television studio in which he was about to appear with an hallucinogenic drug and contaminating his shoes with thallium which they believed would cause the hair in his beard to fall out.

These schemes were rejected and instead Richard Bissell decided to arrange the assassination of Fidel Castro. In September 1960, Bissell and Allen W. Dulles, the director of the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA), initiated talks with two leading figures of the Mafia, Johnny Roselli and Sam Giancana. Later, other crime bosses such as Carlos Marcello, Santos Trafficante and Meyer Lansky became involved in this plot against Castro.

Robert Maheu, a veteran of CIA counter-espionage activities, was instructed to offer the Mafia $150,000 to kill Fidel Castro. The advantage of employing the Mafia for this work is that it provided CIA with a credible cover story. The Mafia were known to be angry with Castro for closing down their profitable brothels and casinos in Cuba. If the assassins were killed or captured the media would accept that the Mafia were working on their own.

The Federal Bureau of Investigation had to be brought into this plan as part of the deal involved protection against investigations against the Mafia in the United States. Castro was later to complain that there were twenty ClA-sponsered attempts on his life. Eventually Johnny Roselli and his friends became convinced that the Cuban revolution could not be reversed by simply removing its leader. However, they continued to play along with this CIA plot in order to prevent them being prosecuted for criminal offences committed in the United States.

Lansdale later claimed that John F. Kennedy asked him to draft a contingency plan to overthrow Fidel Castro. But he added that the idea had not been viable because it depended on recruiting Cuban exiles to generate an uprising in Cuba, something that he said was impossible.

In 1963 Kennedy asked Lansdale to concentrate on the situation in Vietnam. However, it was not long before Lansdale was in conflict with General Maxwell Taylor, who was the military representative to the president. Taylor took the view that the war could be won by military power. He argued in the summer of 1963 that 40,000 US troops could clean up the Vietminh threat in Vietnam and another 120,000 would be sufficient to cope with any possible North Vietnamese or Chinese intervention.

Lansdale disagreed with this viewpoint. He had spent years studying the way Mao Zedong had taken power in China. He often quoted Mao of telling his guerrillas: "Buy and sell fairly. Return everything borrowed. Indemnify everything damaged. Do not bathe in view of women. Do not rob personal belongings of captives." The purpose of such rules, according to Mao, was to create a good relationship between the army and its people. This was a strategy that had been adopted by the National Liberation Front. Lansdale believed that the US Army should adopt a similar approach. As Cecil B. Currey, the author of Edward Lansdale: The Unquiet American pointed out: "Lansdale was a dedicated anticommunist, conservative in his thoughts. Many people of like persuasion were neither as willing to study their enemy nor as open to adopting communist ideas to use a countervailing force. If for no other reason, the fact makes Lansdale stand out in bold relief to the majority of fellow military men who struggled on behalf of America in those intense years of the cold war."

Edward Lansdale also argued against the overthrow of Ngo Dinh Diem. He told Robert McNamara that: "There's a constitution in place… Please don't destroy that when you're trying to change the government. Remember there's a vice president (Nguyen Ngoc Tho) who's been elected and is now holding office. If anything happens to the president, he should replace him. Try to keep something sustained."

It was these views that got him removed from office. The pressure to remove Lansdale came from General Curtis LeMay and General Victor Krulak and other senior members of the military. As a result it was decided to abolish his post as assistant to the secretary of defence. He was awarded the Distinguished Service Medal for counter-insurgency work and became consultant to the the Food for Peace programme.

Lansdale continued to argue against Lyndon Johnson's decision to try and use military power to win the Vietnam War. When General William Westmoreland argued that: "We're going to out-guerrilla the guerrilla and out-ambush the ambush… because we're smarter, we have greater mobility and fire-power, we have more endurance and more to fight for… And we've got more guts." Lansdale replied: "All actions in the war should be devised to attract and then make firm the allegiance of the people." He added "we label our fight as helping the Vietnamese maintain their freedom" but when "we bomb their villages, with horrendous collateral damage in terms of both civilian property and lives… it might well provoke a man of good will to ask, just what freedom of what Vietnamese are we helping to maintain?"

Lansdale quoted Robert Taber (The War of the Flea): "There is only one means of defeating an insurgent people who will not surrender, and that is extermination. There is only one way to control a territory that harbours resistance, and that is to turn it into a desert. Where these means cannot, for whatever reason, be used, the war is lost." Lansdale thought this was the situation in Vietnam and wrote to a friend that if the solution was to "kill every last person in the enemy ranks" then he was "not only morally opposed" to this strategy but knew it was "humanly impossible".

Lansdale added "No idea can be bombed or beaten to death. Military action alone is never enough." He pointed out that since 1945 the Vietminh had been willing to fight against the strength of both France and the United States in order to ensure success of their own. "Without a better idea, rebels will eventually win, for ideas are defeated only by better ideas."

Lansdale was anti-communist because he really believed in democracy. Lansdale had been arguing since 1956 that the best way of dealing with the National Liberation Front was to introduce free elections that included the rights of Chams, Khmers, Montagnards and other minorities to participate in voting. Lansdale said that he went into Vietnam as Tom Paine would have done. He was found of quoting Paine as saying: "Where liberty dwells not, there is my country."

Lansdale also distanced himself from the Freedom Studies Center of the Institute for American Strategy when he discovered it was being run by the John Birch Society. He told a friend: "I refused to have anything more to do with it… That isn't what our country is all about." Lansdale considered himself a "conservative moderate" who was tolerant of all minorities.

Lansdale continued to advocate a non-military solution to Vietnam and in 1965, under orders from President Lyndon B. Johnson, the new US ambassador in Saigon, Henry Cabot Lodge, put Lansdale in charge of the "pacification program" in the country. As Newsweek reported: " Lansdale is expected to push hard for a greater effort on the political and economic fronts of the war, while opposing the recent trend bombing and the burning of villages."

One of those who served under him in this job was Daniel Ellsberg. He liked Lansdale because of his commitment to democracy. Ellsberg also agreed with Lansdale that the pacification program should be run by the Vietnamese. He argued that unless it was a Vietnam project it would never work. Lansdale knew that there was a deep xenophobia among Vietnamese. However, as he pointed out, he believed "Lyndon Johnson would have been just as xenophobic if Canadians or British or the French moved in force into the United States and took charge of his dreams for a great Society, told him what to do, and spread out by thousands throughout the nation to see that it got done."

In February 1966 Lansdale was removed from his position in control of the pacification program. However, instead of giving the job to a Vietnamese, William Porter, was given the post. Lansdale was now appointed as a senior liaison officer, with no specific responsibilities.

Unlike most Americans in Vietnam, Lansdale believed it was essential for Vietnamese leaders to claim credit for any changes and reforms. His attitude aroused antagonism in the hearts of many within the U.S. bureaucracy who didn't like the idea of allowing others to receive credit for successful programs – although they did not object to blaming Vietnamese leaders for projects that failed.

Most importantly, Lansdale thought that the military should be careful to avoid causing civilian casualties. As his biographer, Cecil B. Currey pointed out: " Lansdale was primarily concerned about the welfare of people. Such a stance made him anathema to those more concerned about search and destroy missions, agent orange, free fire zones, harassing and interdicting fires, and body counts."

According to Lansdale "we lost the war at the Tet offensive". The reason for this was that after this defeat American commanders lost the ability to discriminate between friend and foe. All Vietnamese were now "gooks". Lansdale complained that commanders resorted more and more on artillery barrages that killed thousands of civilians. He told a friend that: "I don't believe this is a government that can win the hearts and minds of the people." Lansdale resigned and returned to the United States in June 1968.

Lansdale retired in 1968 and his book, The Midst of Wars, was published in 1972. Lansdale argued that the United States could still retain control of third-world nations by exporting ''the American way'' through a blend of economic aid and efforts at ''winning the hearts and the minds of the people.'' Edward Lansdale died in McLean, Virginia, on 23rd February, 1987.

On this day in 1911 George Barnes resigned as chairman of the Labour Party. At the next meeting of MPs, Ramsay MacDonald was elected unopposed to replace Barnes. Arthur Henderson now became secretary. According to Philip Snowden, a bargin had been struck at the party conference the previous month, whereby MacDonald was to resign the secretaryship in Henderson's favour, in return for becoming chairman."

In 1914 Barnes strongly supported Britain's involvement in the First World War. He toured industrial districts making recruitment speeches. Barnes also went to Canada where he helped to persuade trained mechanics to work in British industry. Barnes's youngest son, Henry, was killed fighting on the Western Front in September 1915. This did not change his views on the war and in 1916 was one of the few Labour MPs to support military conscription.

Barnes became disillusioned with the way Herbert Asquith was running the country and in 1916 helped David Lloyd George gain power. Lloyd George rewarded him by making George Barnes head of the recently formed Pensions Ministry.

At the end of the war the Labour Party withdrew from Lloyd George's coalition government. Barnes resigned from the party in order to remain as Minister of Pensions. He remained in the post until he resigned for reasons of poor health in January 1920.

On this day in 1915 at an executive meeting in Buxton in 1915 all the officers of the National Union of Women's Suffrage Societies (except the Treasurer) and ten members of the National Executive resigned over the decision not to support the Women's Peace Congress at the Hague. This included Chrystal Macmillan, Margaret Ashton, Kathleen Courtney, Catherine Marshall, Eleanor Rathbone and Maude Royden. "Wounding language was used on both sides. Mrs Fawcett did not normally turn disagreements among friends into quarrels but this one she experienced as a personal betrayal. It became the only episode in her life that she wished to forget".

Kathleen Courtney wrote when she resigned: "I feel strongly that the most important thing at the present moment is to work, if possible on international lines for the right sort of peace settlement after the war. If I could have done this through the National Union, I need hardly say how infinitely I would have preferred it and for the sake of doing so I would gladly have sacrificed a good deal. But the Council made it quite clear that they did not wish the union to work in that way." According to Elizabeth Crawford: "Mrs Fawcett afterwards felt particularly bitter towards Kathleen Courtney, whom she felt had been intentionally and personally wounding, and refused to effect any reconciliation, relying, as she said, on time to erase the memory of this difficult period."

On this day in 1912 the historian Christopher Hill, the son of a solicitor, was born in York. His parents were Methodists and he later claimed this had an important influence on his political development. He attended St. Peter's School and his academic ability was so obvious that he was recruited by Vivien Galbraith, a don at Balliol College, at the age of sixteen.

Hill became a Marxist while at Oxford University. He later admitted that this was a result of attending the Thursday Lunch Club organized by G. D. H. Cole. Hill pointed out that at these meetings "I was forced to ask questions about my own society which had previously not occurred to me."

In 1935 Hill joined the Communist Party of Great Britain and spent a year in the Soviet Union. On his return he became an assistant lecturer at University College. After two years in Cardiff he returned to Balliol College as a tutor in modern history. After long discussions with A. L. Morton, Hill published his influential article, The English Revolution 1640 (1940). He later recalled how he wrote it "as a very angry man believing I was going to be killed in the war."

In 1940 Hill joined joined the British Army. He served as a lieutenant in the Oxford and Bucks Light Infantry before becoming a major in the intelligence corps. In 1943 he was seconded to the British Foreign Office where he remained for the rest of the Second World War.

Hill joined E. P. Thompson, Eric Hobsbawm, Rodney Hilton, A. L. Morton, Raphael Samuel, George Rudé, John Saville, Dorothy Thompson, Edmund Dell, Victor Kiernan and Maurice Dobb in forming the Communist Party Historians' Group. Saville later wrote: "The Historian's Group had a considerable long-term influence upon most of its members. It was an interesting moment in time, this coming together of such a lively assembly of young intellectuals, and their influence upon the analysis of certain periods and subjects of British history was to be far-reaching."

In 1947 Hill published Lenin and the Russian Revolution. Two years later Hill and Edmund Dell published the path-breaking collection of documents on the English Civil War, The Good Old Cause (1949). Hill published Economic Problems of the Church in 1955. John Saville argued in his autobiography, Memoirs from the Left, that Hill in the 1950s was a historian of growing reputation and "a man of notable integrity: characteristics which have remained throughout his life."

During this period MI5 and police special branch officers tapped and recorded his telephone calls, intercepted his private correspondence and monitored his contacts. MI5 said the object of keeping checks on Hill to establish “the identity of his contacts at the University (of Oxford) and in the cultural field generally, and to obtain the names of intellectuals sympathetic to the (Communist) party who may not already be known to us”.

A MI5 report in 1950 revealed how Hill’s first wife, Inez, was unhappy with his political activities, which she had previously shared. “There seems to be some reason to believe that she is not only fed up with her husband’s politics but also with her husband’s political activities, especially as his political sympathies lead him, according to her, to give a considerable amount of his money to the party.”

Hill was disillusioned by the events in the Soviet Union and the invasion of Hungary. MI5 files show that at a meeting at the party’s headquarters at King Street, at the end of 1956, Hill, Eric Hobsbawm and Doris Lessing agreed to write a letter attacking the party leadership’s “uncritical support … to Soviet action in Hungary”, a reference to the crushing of the uprising there. That support, the letter explained, was “the undesirable culmination of years of distortion of facts”. Hill, who left the party a year later, used the phrase “the crimes of Stalin” at the meeting, according to the MI5 report. The party’s paper, The Daily Worker, refused to publish the letter. Hill left the Communist Party of Great Britain in 1957.

Books by Hill included Puritanism and Revolution (1958), The Century of Revolution (1961), Society and Puritanism in Pre-Revolutionary England (1964), Intellectual Origins of the English Revolution (1965),Reformation to Industrial Revolution (1967), God's Englishman (1970), The World Turned Upside Down (1972) and The Levellers and the English Revolution (1977).

After retiring as Master of Balliol he worked as a visiting professor at the Open University. He also published Intellectual Consequences of the English Revolution (1980), The World of Muggletonians (1983), The Experience of Defeat (1984), The English Bible in 17th Century England (1993), Liberty Against the Law (1996) and The Changing Politics of Foreign Policy (2002).

Christopher Hill died on 24th February, 2003.

On this day in 1914 a group of supporters of women's suffrage, who were disillusioned by the lack of success of the National Union of Women's Suffrage Societies and disapproved of the arson campaign of the Women Social & Political Union, decided to form the United Suffragists movement.

Membership was open to both men and women, militants and non-militants. Members included Henry Harben, Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence, Frederick Pethick-Lawrence, Evelyn Sharp, Mary Neal, Henry Nevinson, Margaret Nevinson, Hertha Ayrton, Barbara Ayrton Gould, Gerald Gould, Israel Zangwill, Edith Zangwill, Lena Ashwell, Louisa Garrett Anderson, Eveline Haverfield, Maud Arncliffe Sennett, John Scurr, Julia Scurr and Laurence Housman.

On this day in 1918 British women over the age of 30 who meet minimum property qualifications get the right to vote. In January, 1917, the House of Commons began discussing the possibility of granting women the vote in parliamentary elections. Herbert Asquith, the Prime Minister during the militant suffrage campaign, had always been totally against women having the vote. However, during the debate he confessed he had changed his mind and now supported the claims of the NUWSS, WSPU and the Women's Freedom League.

On 28th March, 1917, the House of Commons voted 341 to 62 that women over the age of 30 who were householders, the wives of householders, occupiers of property with an annual rent of £5 or graduates of British universities. MPs rejected the idea of granting the vote to women on the same terms as men. The Qualification of Women Act eventually became law on 6th February 1918. Lilian Lenton, who had played an important role in the militant campaign later recalled: "Personally, I didn't vote for a long time, because I hadn't either a husband or furniture, although I was over 30."

Soon afterwards Emmeline Pankhurst and Christabel Pankhurst established the The Women's Party. Its twelve-point programme included: (1) A fight to the finish with Germany. (2) More vigorous war measures to include drastic food rationing, more communal kitchens to reduce waste, and the closing down of nonessential industries to release labour for work on the land and in the factories. (3) A clean sweep of all officials of enemy blood or connections from Government departments. Stringent peace terms to include the dismemberment of the Hapsburg Empire." The party also supported: "equal pay for equal work, equal marriage and divorce laws, the same rights over children for both parents, equality of rights and opportunities in public service, and a system of maternity benefits." Christabel and Emmeline had now completely abandoned their earlier socialist beliefs and advocated policies such as the abolition of the trade unions.

After the passing of the Qualification of Women Act the first opportunity for women to vote was in the General Election in December, 1918. Seventeen women candidates that stood in the post-war election. Christabel Pankhurst represented the The Women's Party in Smethwick. Despite the fact that the Conservative Party candidate agreed to stand down, she lost a straight fight with the representative of the Labour Party by 775 votes. Only one woman, Constance Markiewicz, standing for Sinn Fein, was elected. However, as a member of Sinn Fein, she refused to take her seat in the House of Commons.

Nancy Astor beat the Liberal Party candidate, Isaac Foot, and on 1st December 1919 became the first woman to take her seat in the House of Commons. Constance Markievicz, like many feminists, was highly critical that a woman who had not been part of the suffrage campaign had been elected to parliament. She accused her being a member of the "upper classes" and "out of touch" with the needs of ordinary people. Norah Dacre Fox, one of the leaders of the Women's Social and Political Union pointed out: "the first woman to be elected for an English constituency was an American born citizen, who had no credentials to represent British women in their own parliament save that she had married a British subject."

On this day in 1933 civil rights leader Walter Edward Fauntroy was born in Washington. After attending Yale University Divinity School he became the pastor of the New Bethel Baptist Church. An active member of the civil rights movement Fauntroy was a member of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC), an organization led by Martin Luther King, Ralph David Abernathy, Fred Shutterworth, and Bayard Rustin.

In 1961, Fauntroy was appointed by Martin Luther King as director of the Washington Bureau of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference. He then worked as the Washington coordinator of the 1963 March on Washington and two years later directed the Selma March.

In 1966 President Lyndon B. Johnson appointed Fauntroy vice chairman of the White House's "To Fulfill These Rights" conference. The following year Johnson appointed him vice chairman of the Council of the District of Columbia. In 1969 Fauntroy became national coordinator of the Poor People's Campaign.

A member of the Democratic Party in 1971 Fauntroy was elected to Congress. In 1975, Frank Church became the chairman of the Select Committee to Study Governmental Operations with Respect to Intelligence Activities. In its final report, issued in April 1976, the Select Committee to Study Governmental Operations with Respect to Intelligence Activities concluded: “Domestic intelligence activity has threatened and undermined the Constitutional rights of Americans to free speech, association and privacy. It has done so primarily because the Constitutional system for checking abuse of power has not been applied.”

The committee also reported that the Central Intelligence Agency had withheld from the Warren Commission, during its investigation of the assassination of John F. Kennedy, information about plots by the Government of the United States against Fidel Castro of Cuba; and that the Federal Bureau of Investigation had conducted a counter-intelligence program (COINTELPRO) against Martin Luther King and the Southern Christian Leadership Conference.

As a result of Church's report Congress established the House Select Committee on Assassinations in September 1976. The resolution authorized a 12-member select committee to conduct an investigation of the circumstances surrounding the deaths of John F. Kennedy and Martin Luther King.

Louis Stokes was named chairman of the committee. Two subcommittees were created - a subcommittee on the assassination of President Kennedy, with Richardson Preyer of North Carolina as its chairman, and a subcommittee on the assassination of Dr. King, with Fauntroy as its chairman. In 1979 the House Select Committee on Assassinations reported that there was "a high probability that two gunmen fired at President John F. Kennedy" in Dallas.

On this day in 1947 Ellen Wilkinson took an overdose of barbiturates. Following the 1945 General Election, the new Prime Minister, Clement Attlee, appointed Wilkinson as Minister of Education, the first woman in British history to hold the post. Wilkinson's plans to increase the school-leaving age to sixteen had to be abandoned when the government decided that the measure would be too expensive. However, she did managed to persuade Parliament to pass the 1946 School Milk Act that gave free milk to all British schoolchildren. It is claimed that depressed by her failure to bring in all the reforms she believed necessary, she committed suicide.

On this day in 1952 King George VI died at Sandringham, Norfolk. George Saxe-Coburg-Gotha was born in Sandringham, Norfolk, on 14th December, 1895. George was the great-grandson of Queen Victoria and his father was George V, who became king of the United Kingdom in 1910. George's elder brother, Edward, was therefore heir to the throne.

George was a sickly child and was often ill. He also developed an acute stammer. In 1909 he was sent to Osborne as a naval cadet but passed out bottom of his class. After attending Dartmouth he joined the Royal Navy as a midshipman, but suffering bouts of acute gastritis, did not see action in the First World War until serving on HMS Collingwood at the Battle of Jutland.

The outbreak of the First World War created problems for the royal family because of its German background. Owing to strong anti-German feeling in Britain, it was decided to change the name of the royal family from Saxe-Coburg-Gotha to Windsor. To stress his support for the British, George V made several visits to the Western Front.

In 1917 George joined the Royal Naval Air Service and later the recently formed Royal Air Force (1919). However, George did not qualify as a pilot until 1919 and therefore did not take part in the highly dangerous air war.

After the war George attended Trinity College, Cambridge, but only stayed for a year. In 1920 he was created the Duke of York and carried out public duties for his father. Three years later he married Elizabeth Bowles-Lyon. The couple had two children, Elizabeth (1926) and Margaret (1930).

George also became president of the Industrial Welfare Society. In this role he visited so many factories that he became known as the "Industrial Duke". He also made royal tours of East Africa, Australia and New Zealand.

George's marriage had the approval of his father, George V. However, his brother, Edward, the heir to the throne, had developed a relationship with Wallis Simpson, an American woman who was married to Ernest Simpson. This was her second marriage and had divorced her first husband, E. W. Spencer in 1927.

George V died on 20th January, 1936. Edward VIII now became king and his relationship with Wallis Simpson was reported in the foreign press. The government instructed the British press not to refer to the relationship. The prime minister, Stanley Baldwin, urged the king to consider the constitutional problems of marrying a divorced woman.

Although Edward VIII received the political support from Winston Churchill and Lord Beaverbrook, he was aware that his decision to marry Wallis Simpson would be unpopular with the British public. The Archbishop of Canterbury also made it clear he was strongly opposed to the king's relationship.

On 10th December, 1936, the king signed a document that stated he he had renounced "the throne for myself and my descendants." The following day he made a radio broadcast where he told the nation that he had abdicated because he found he could not "discharge the duties of king as I would wish to do without the help and support of the woman I love."

George now became king and the coronation took place on 12th May, 1937. Later that month, Neville Chamberlain replaced Stanley Baldwin as prime-minister. The following year Chamberlain travelled to Germany to meet Adolf Hitler in an attempt to avoid war between the two countries. The result of Chamberlain's appeasement policy was the signing of the Munich Agreement.

Crowds cheered all along Chamberlain's route from the airport back to Buckingham Palace, where he was to brief King George VI on the incredible turn of events. He was greeted by more cheering crowds outside 10 Downing Street as he arrived home. A few minutes later, Chamberlain was persuaded to step forwards and make a speech from the first-floor window: "My good friends: this is the second time in our history that there has come back to Downing Street from Germany peace with honour. I believe it is peace for our time."

Several ministers, including Duff Cooper, Oliver Stanley, Harry Crookshank and Leslie Hore-Belisha, were very unhappy with the Munich Agreement. Cooper explained how he felt as he arrived at 10 Downing Street following the signing of the agreement: "I was caught up in the large crowd that were demonstrating their enthusiasm and were cheering, laughing, and singing; and there is no greater feeling of loneliness than to be in a crowd of happy, cheerful people and to feel that there is no occasion for oneself for gaiety or for cheering. That there was every cause for relief I was deeply aware, as much as anybody in this country, but that there was great cause for self-congratulation I was uncertain."

Chamberlain pleaded with the men to stay in the government in order to give an image of unity. However, on 3rd October, Cooper resigned. After a brief interview with Chamberlain, he made his way to Buckingham Palace to hand in his seals of office. King George VI was polite but frank: "He said he could not agree with me, but he respected those who had the courage of their convictions." That evening the King issued a statement: "The time of anxiety is past. After the magnificent efforts of the Prime Minister in the cause of peace it is my fervent hope that a new era of friendship and prosperity may be dawning among the peoples of the world."

On 3rd September, 1939, Neville Chamberlain went on radio to announce: "Britain is at war with Germany" and went on to say: "This is a sad day for all of us, and to none is it sadder than to me. Everything that I have worked for, everything that I have hoped for, everything that I have believed in during my public life, has crashed into ruins. There is only one thing left for me to do; that is, to devote what strength and powers I have to forwarding the victory of the cause for which we have to sacrifice so much. I cannot tell what part I may be allowed to play myself; I trust I may live to see the day when Hitlerism has been destroyed and a liberated Europe has been re-established."

Considered an uninspiring war leader, members of the Labour Party and Liberal Party refused to serve in his proposed National Government. Chamberlain resigned and was replaced by Winston Churchill. The king had been against Churchill's appointment but the two men eventually became close allies. Later the king wrote in his diary: "I could not have a better prime minister."

The king and queen many several tours of Britain's bombed cities during the Second World War. In September, 1940, Buckingham Palace was badly damaged during a raid. His wife, Queen Elizabeth, remarked: "I'm glad we've been bombed. It makes me feel I can look the East End in the face."

In 1943 the king flew out to North Africa to visit the troops after their victory at El Alamein. He also visited Malta and was present at discussions about the D-Day invasion. Soon after a bridgehead had been created, the king arrived in Normandy to meet the troops.

After the war the king enjoyed a reasonable relationship with his new prime minister, Clement Attlee. He was opposed to socialism and unsuccessfully attempted to persuade him not to nationalize several of Britain's main industries.

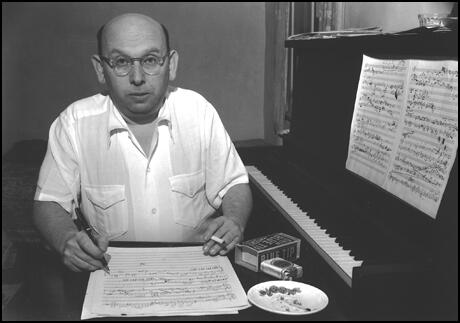

On this day in 1962 Hanns Eisler died. Eisler was born in Germany on 6th July, 1898. The son of the Austrian philosopher Rudolf Eisler and Marie Fischer, the daughter of a butcher.

In 1916 Eisler was recruited into the Hungarian regiment of the Austro-Hungarian Army. He was wounded several times during the First World War and when fighting ceased in 1918 he returned to Vienna. A socialist, Eisler supported the failed Spartacist Uprising in January, 1919.

Over the next few years Eisler studied with Anton von Webern in Vienna and composed Piano Sonarto No. 1 (1923), Palmstrom (1924), Zeitungsausschnitte (1926), The Red Megaphone (1927), Songs for the Struggle (1928) and Song of the Unemployed (1929).

A committed Marxist, Eisler worked with Bertolt Brecht on the musical play, The Measure Taken (1930). He also wrote the music for several German films including Hell on Earth (1931), Song of Heroes (1932), To Whom Does the World Belong (1932) and The Song of the Street (1933).

When Adolf Hitler gained power in 1933, Eisler he was forced to flee from Germany. He settled in the United States where he wrote the music for several Hollywood movies including: The 400 Million (1939), The Forgotten Village (1941), Hangman Also Die (1943), None But the Lonely Heart (1944), Jealousy (1945), A Scandal in Paris (1946) and Deadline at Dawn (1946).

In 1947 the House of Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC), chaired by J. Parnell Thomas, began an investigation into the entertainment industry. The HUAC interviewed 41 people who were working in Hollywood. These people attended voluntarily and became known as "friendly witnesses". During their interviews they named nineteen people who they accused of holding left-wing views.

Eisner was one of those named and like his left-wing friend, Bertolt Brecht, was forced to leave the United States. Eisler moved to East Germany where he continued to write music for the cinema and the theatre. Hanns Eisler, who wrote the East German national anthem, Auferstanden aus Ruinen, died on 6th February, 1962.