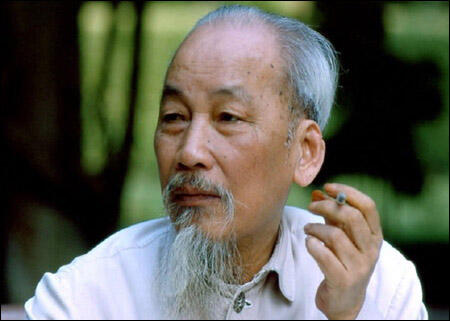

Ho Chi Minh

Ho Chi Minh was born in Vietnam in 1890. His father, Nguyen Sinh Huy was a teacher employed by the French.

He had a reputation for being extremely intelligent but his unwillingness to learn the French language resulted in the loss of his job. To survive, Nguyen Sinh Huy was forced to travel throughout Vietnam, offering his services to the peasants. This usually involved writing letters and providing medical care.

As a nationalist, Nguyen taught his children to resist the rule of the French. Not surprisingly, they all grew up to be committed nationalists willing to fight for Vietnamese independence.

Ho Chi Minh's sister obtained employment working with the French Army. She used this position to steal weapons that she hoped one day would be used to drive the French out of Vietnam. She was eventually caught and was sentenced to life imprisonment. Although he had refused to learn French himself, Nguyen decided to send Ho to a French school. He was now of the opinion that it would help him prepare for the forthcoming struggle against the French.

After his studies. Ho was, for a short period, a schoolteacher. He then decided to become a sailor. This enabled him to travel to many different countries. This included several countries that were part of the French Empire. In doing so. Ho learnt that the Vietnamese were not the only people suffering from exploitation.

Ho finally settled in Paris in 1917. Here he read books by Karl Marx and other left-wing writers and eventually he became convened to communism. When in December, 1920 the French Communist Party was formed. Ho became one of its founder members.

Ho, like the rest of the French Communist Party, had been inspired by the Russian Revolution. In 1924, he visited the Soviet Union. While in Moscow, Ho wrote to a friend that it was the duty of all communists to return to their own country to: "make contact with the masses to awaken, organise, unite and train them, and lead them to fight for freedom and independence."

However, Ho was aware that if he returned to Vietnam he was in danger of being arrested by the French authorities. He therefore decided to go and live in China on the Vietnam border. Here he helped organise other exiled nationalists into the 'Vietnam Revolutionary League'.

In September, 1940, the Japanese army invaded Indochina. With Paris already occupied by Germany, the French troops decided it was not worth putting up a fight and they surrendered to the Japanese. Ho Chi Minh and his fellow nationalists saw this as an opportunity to free their country from foreign domination and formed an organisation called the Vietminh. Under the military leadership of General Vo Nguyen Giap, the Vietminh began a guerrilla campaign against the Japanese.

The Vietminh received weapons and ammunition from the Soviet Union, and after the bombing of Pearl Harbour, they also obtained supplies from the United States. During this period the Vietminh leant a considerable amount about military tactics which was to prove invaluable in the years that were to follow.

When the Japanese surrendered to the Allies after the dropping of atom bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki in August, 1945, the Vietminh was in a good position to take over the control of the country.

In September, 1945, Ho Chi Minh announced the formation of the Democratic Republic of Vietnam. Unknown to the Vietminh Franklin D. Roosevelt, Winston Churchill and Joseph Stalin had already decided what would happen to post-war Vietnam at a summit-meeting at Potsdam. It had been agreed that the country would be divided into two, the northern half under the control of the Chinese and the southern half under the British.

After the Second World War France attempted to re-establish control over Vietnam. In January 1946, Britain agreed to remove her troops and later that year, China left Vietnam in exchange for a promise from France that she would give up her rights to territory in China.

France refused to recognise the Democratic Republic of Vietnam that had been declared by Ho Chi Minh and fighting soon broke out between the Vietminh and the French troops. At first, the Vietminh under General Vo Nguyen Giap, had great difficulty in coping with the better trained and equipped French forces. The situation improved in 1949 after Mao Zedong and his communist army defeated Chaing Kai-Shek in China. The Vietminh now had a safe-base where they could take their wounded and train new soldiers.

By 1953 the Vietminh controlled large areas of North Vietnam. The French, however, had a firm hold on the south and had installed Bo Dai, the former Vietnamese Emperor, as the Chief of State.

When it became clear that France was becoming involved in a long-drawn out war, the French government tried to negotiate a deal with the Vietminh. They offered to help set-up a national government and promised they would eventually grant Vietnam its independence. Ho Chi Minh and the other leaders of the Vietminh did not trust the word of the French and continued the war.

French public opinion continued to move against the war. There were four main reasons for this: (1) Between 1946 and 1952 90,000 French troops had been killed, wounded or captured; (2) France was attempting to build up her economy after the devastation of the Second World War. The cost of the war had so far been twice what they had received from the United States under the Marshall Plan; (3) The war had lasted seven years and there was still no sign of an outright French victory; (4) A growing number of people in France had reached the conclusion that their country did not have any moral justification for being in Vietnam.

General Navarre, the French commander in Vietnam, realised that time was running out and that he needed to obtain a quick victory over the Vietminh. He was convinced that if he could manoeuvre General Vo Nguyen Giap into engaging in a large scale battle, France was bound to win. In December, 1953, General Navarre setup a defensive complex at Dien Bien Phu, which would block the route of the Vietminh forces trying to return to camps in neighbouring Laos. Navarre surmised that in an attempt to reestablish the route to Laos, General Giap would be forced to organise a mass-attack on the French forces at Dien Bien Phu.

Navarre's plan worked and General Giap took up the French challenge. However, instead of making a massive frontal assault, Giap choose to surround Dien Bien Phu and ordered his men to dig a trench that encircled the French troops. From the outer trench, other trenches and tunnels were dug inwards towards the centre. The Vietminh were now able to move in close on the French troops defending Dien Bien Phu.

While these preparations were going on, Giap brought up members of the Vietminh from all over Vietnam. By the time the battle was ready to start, Giap had 70,000 soldiers surrounding Dien Bien Phu, five times the number of French troops enclosed within.

Employing recently obtained anti-aircraft guns and howitzers from China, Giap was able to restrict severely the ability of the French to supply their forces in Dien Bien Phu. When Navarre realised that he was trapped, he appealed for help. The United States was approached and some advisers suggested the use of tactical nuclear weapons against the Vietminh. Another suggestion was that conventional air-raids would be enough to scatter Giap's troops.

The United States President, Dwight Eisenhower, however, refused to intervene unless he could persuade Britain and his other western allies to participate. Winston Churchill, the British Prime Minister, declined claiming that he wanted to wait for the outcome of the peace negotiations taking place in Geneva before becoming involved in escalating the war.

On March 13, 1954, Vo Nguyen Giap launched his offensive. For fifty-six days the Vietminh pushed the French forces back until they only occupied a small area of Dien Bien Phu. Colonel Piroth, the artillery commander, blamed himself for the tactics that had been employed and after telling his fellow officers that he had been "completely dishonoured" committed suicide by pulling the safety pin out of a grenade.

The French surrendered on May 7th. French casualties totalled over 7,000 and a further 11,000 soldiers were taken prisoner. The following day the French government announced that it intended to withdraw from Vietnam. The following month the foreign ministers of the United States, the Soviet Union, Britain and France decided to meet in Geneva to see if they could bring about a peaceful solution to the conflicts in Korea and Vietnam.

After much negotiation the following was agreed: (1) Vietnam would be divided at the 17th parallel; (2) North Vietnam would be ruled by Ho Chi Minh; (3) South Vietnam would be ruled by Ngo Dinh Diem, a strong opponent of communism; (4) French troops would withdraw from Vietnam; (5) the Vietminh would withdraw from South Vietnam; (6) the Vietnamese could freely choose to live in the North or the South; and (7) a General Election for the whole of Vietnam would be held before July, 1956, under the supervision of an international commission.

After their victory at Dien Bien Phu, some members of the Vietminh were reluctant to accept the cease-fire agreement. Their main concern was the division of Vietnam into two sections. However, Ho Chi Minh argued that this was only a temporary situation and was convinced that in the promised General Election, the Vietnamese were sure to elect a communist government to rule a re-united Vietnam.

This view was shared by President Dwight Eisenhower. As he wrote later: "I have never talked or corresponded with a person knowledgeable in Indochinese affairs who did not agree that had elections been held at the time of the fighting, possibly 80 per cent of the population would have voted for the communist Ho Chi Minh."

When the Geneva conference took place in 1954, the United States delegation proposed the name of Ngo Dinh Diem as the new ruler of South Vietnam. The French argued against this claiming that Diem was "not only incapable but mad". However, eventually it was decided that Diem presented the best opportunity to keep South Vietnam from falling under the control of communism.

When it became clear that Ngo Dinh Diem had no intention of holding elections for a united Vietnam, his political opponents began to consider alternative ways of obtaining their objectives. Some came to the conclusion that violence was the only way to persuade Diem to agree to the terms of the 1954 Geneva Conference. The year following the cancelled elections saw a large increase in the number of people leaving their homes to form armed groups in the forests of Vietnam. At first they were not in a position to take on the South Vietnamese Army and instead concentrated on what became known as 'soft targets'. In 1959, an estimated 1,200 of Diem's government officials were murdered.

Ho Chi Minh was initially against this strategy. He argued that the opposition forces in South Vietnam should concentrate on organising support rather than carrying out acts of terrorism against Diem's government.

In 1959, Ho Chi Minh sent Le Duan, a trusted adviser, to visit South Vietnam. Le Duan returned to inform his leader that Diem's policy of imprisoning the leaders of the opposition was so successful that unless North Vietnam encouraged armed resistance, a united country would never be achieved.

Ho Chi Minh agreed to supply the guerrilla units with aid. He also encouraged the different armed groups to join together and form a more powerful and effective resistance organisation. This they agreed to do and in December, 1960, the National Front for the Liberation of South Vietnam (NLF) was formed. The NLF, or the 'Vietcong', as the Americans were to call them, was made up of over a dozen different political and religious groups. Although the leader of the NLF, Hua Tho, was a non-Marxist, Saigon lawyer, large numbers of the movement were supporters of communism.

The strategy and tactics of the NLF were very much based on those used by Mao Zedong in China. This became known as Guerrilla Warfare. The NLF was organised into small groups of between three to ten soldiers. These groups were called cells. These cells worked together but the knowledge they had of each other was kept to the bare minimum. Therefore, when a guerrilla was captured and tortured, his confessions did not do too much damage to the NLF.

The initial objective of the NLF was to gain the support of the peasants living in the rural areas. According to Mao Zedong, the peasants were the sea in which the guerrillas needed to swim: "without the constant and active support of the peasants... failure is inevitable."

When the NLF entered a village they obeyed a strict code of behaviour. All members were issued with a series of 'directives'. These included:" (1) Not to do what is likely to damage the land and crops or spoil the houses and belongings of the people; (2) Not to insist on buying or borrowing what the people are not willing to sell or lend; (3) Never to break our word; (4) Not to do or speak what is likely to make people believe that we hold them in contempt; (5) To help them in their daily work (harvesting, fetching firewood, carrying water, sewing, etc.)."

Three months after being elected president in 1964, Lyndon B. Johnson launched Operation Rolling Thunder. The plan was to destroy the North Vietnam economy and to force her to stop helping the guerrilla fighters in the south. Bombing was also directed against territory controlled by the NLF in South Vietnam. The plan was for Operation Rolling Thunder to last for eight weeks but it lasted for the next three years. In that time, the US dropped 1 million tons of bombs on Vietnam.

Ho Chi Minh died in 1969.

Primary Sources

(1) Ho Chi Minh visited the United States just after the First World War. He wrote about lynching for a French magazine in 1924.

When everybody has had enough, the corpse is brought down. The rope is cut into small pieces which will be sold for three or four dollars each.

From 1889 to 1919, 2,600 blacks were lynched, including 51 women and girls and ten former Great War soldiers.

Among the charges brought against the victims of 1919, we note: one of having distributed revolutionary publications; one for expressing his opinion on lynchings too frequently; one of having been known as a leader of the cause of the blacks.

In 30 years, 708 whites, including 11 women, have been lynched. Some for having organized strikes, others for having espoused the cause of the blacks.

(2) Vietminh directives (1948)

(1) Not to do what is likely to damage the land and crops or spoil the houses and belongings of the people.

(2) Not to insist on buying or borrowing what the people are not willing to sell or lend.

(3) Never to break our word.

(4) Not to do or speak what is likely to make people believe that we hold them in contempt.

(5) To help them in their daily work (harvesting, fetching firewood carrying water, sewing, etc.)

(6) In spare time, to tell amusing, simple, and short stories useful to the Resistance, but not to betray secrets.

(7) Whenever possible to buy commodities for those who live far from the market.

(8) To teach the population the national script and elementary hygiene.

(3) President Dwight Eisenhower, Mandate for Change, (1963)

It was generally conceded that had an election been held, Ho Chi Minh would have been elected Premier ... I have never talked or corresponded with a person knowledgeable in Indochinese affairs who did not agree that had elections been held as of the time of the fighting, possibly 80 per cent of the population would have voted for the Communist Ho Chi Minh as their leader.