Selma March

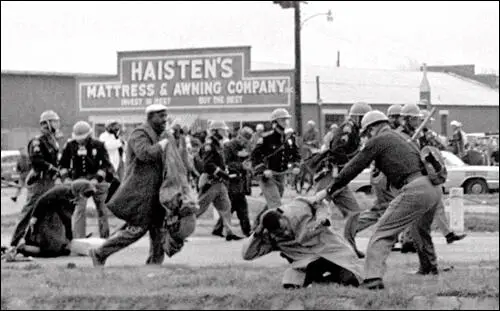

After the murder of Jimmie Lee Jackson during the voter registration drive by the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) it was decided to dramatize the need for a federal registration law. With the help of Martin Luther King and Ralph David Abernathy of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC), leaders of the SCCC organised a protest march from Selma to the state capitol building in Montgomery, Alabama. The first march on 1st February, 1965, led to the arrest of 770 people. A second march, led by John Lewis and Hosea Williams, on 7th March, was attacked by mounted police. The sight of state troopers using nightsticks and tear gas was filmed by television cameras and the event became known as Bloody Sunday.

Martin Luther King led another march of 1,500 people two days later. After crossing the Pettus Bridge the marchers were faced by a barricade of state troopers. King disappointed many of his younger followers when he decided to turn back in order to avoid a confrontation with the troopers. Soon afterwards, one of white ministers on the march, James J. Reeb, was murdered.

President Lyndon B. Johnson now decided to take action and sent troops, marshals and FBI Agents to protect the protesters. On Thursday, 25th March, King led 25,000 people to the Alabama State Capitol and handed a petition to Governor George Wallace, demanding voting rights for African Americans. That night, the Ku Klux Klan killed Viola Liuzzo while returning from the march.

On 6th August, 1965, Lyndon B. Johnson signed the Voting Rights Act. This removed the right of states to impose restrictions on who could vote in elections. Johnson explained how: "Every American citizen must have an equal right to vote. Yet the harsh fact is that in many places in this country men and women are kept from voting simply because they are Negroes." The legislation now empowered the national government to register those whom the states refused to put on the voting list.

Primary Sources

(1) Whitney Young, National Urban League, speech in Selma, Alabama (25th March, 1965)

Now I would like to ask one question to the white citizens of Alabama. How long can you continue to afford the luxury of a political system and public officials who by their rigidity and vulgar racism have today been responsible for bringing in federally controlled troops. Who today and even more so tomorrow will cost this state millions of dollars of federal funds for programs of education, health, welfare, agriculture, etc. Who have discouraged dozens of industries from coming into this state. How long, how long will you continue to be the victims of this self-defeating folly? I say you cannot afford this luxury.

(2) George B. Leonard, The Nation (8th March, 1965)

The chief function of the current Negro movement has been to awaken a nation's conscience.

Such an awakening is painful. It may take years to peel away the layers of self-deception that shut out reality. But there are moments during this process when the senses of an entire nation become suddenly sharper, when pain pours in and the resulting outrage turns to action. One of these moments came, not on Sunday, March 7, when a group of Negroes at Selma were gassed, clubbed and trampled by horses, but on the following day when films of the event appeared on national television.

The pictures were not particularly good. With the cameras rather far removed from the action and the skies partly overcast everything that happened took on the quality of an old newsreel. Yet this very quality, vague and half silhouetted, gave the scene the vehemence and immediacy of a dream. The TV screen showed a column of Negroes standing along a highway. A force of Alabama state troopers blocked their way. As the Negroes drew to a halt, a toneless voice drawled an order from a loudspeaker: In the interests of "public safety," the marchers were being told to turn back. A few moments passed, measured out in silence, as some of the troopers covered their faces with gas masks. There was a lurching movement on the left side of the screen; a heavy phalanx of troopers charged straight into the column, bowling the marchers over.

A shrill cry of terror, unlike any sound that had passed through a TV set, rose up as the troopers lumbered forward, stumbling sometimes on fallen bodies. The scene cut to charging horses, their hoofs flashing over the fallen. Another quick cut: a cloud of tear gas billowed over the highway. Periodically the top of a helmeted head emerged from the cloud, followed by a club on the upswing. The club and the head would disappear into the cloud of gas and another club would bob up and down.

Unhuman. No other word can describe the motions. The picture shifted quickly to a Negro church. The bleeding, broken and unconscious passed across the screen, some of them limping alone, others supported on either side, still others carried in arms or on stretchers. It was at this point that my wife, sobbing, turned and walked away, saying, "I can't look any more."

(3) Martin Luther King, speech (25th March, 1965)

There never was a moment in American history more honorable and more inspiring than the pilgrimage of clergymen and laymen of every race and faith pouring into Selma to face danger at the side of its embattled Negroes.

Confrontation of good and evil compressed in the tiny community of Selma generated the massive power to turn the whole nation to a new course. A president born in the South had the sensitivity to feel the will of the country, and in an address that will live in history as one of the most passionate pleas for human rights ever made by a president of our nation, he pledged the might of the federal government to cast off the centuries-old blight. President Johnson rightly praised the courage of the Negro for awakening the conscience of the nation.

On our part we must pay our profound respects to the white Americans who cherish their democratic traditions over the ugly customs and privileges of generations and come forth boldly to join hands with us. From Montgomery to Birmingham, from Birmingham to Selma, from Selma back to Montgomery, a trail wound in a circle and often bloody, yet it has become a highway up from darkness. Alabama has tried to nurture and defend evil, but the evil is choking to death in the dusty roads and streets of this state.

So I stand before you this afternoon with the conviction that segregation is on its deathbed in Alabama and the only thing uncertain about it is how costly the segregationists and Wallace will make the funeral.

Our whole campaign in Alabama has been centered around the right to vote. In focusing the attention of the nation and the world today on the flagrant denial of the right to vote, we are exposing the very origin, the root cause, of racial segregation in the Southland.