Royal Naval Air Service

In the early part of the 20th century the British Royal Navy used balloons and airships for reconnaissance. After the failure of the Royal Navy's airship Mayfly in 1911, the naval minister, Winston Churchill, began arguing for the development of military aircraft.

In 1912 the government formed the Royal Flying Corps. The British Navy was given the airships owned by the British Army. It was also given twelve aircraft to be used in conjunction with its ships. The first flight from a moving ship took place in May 1912. The following year, the first seaplane carrier, Hermes, was commissioned. The Navy also began to build a chain of coastal air stations.

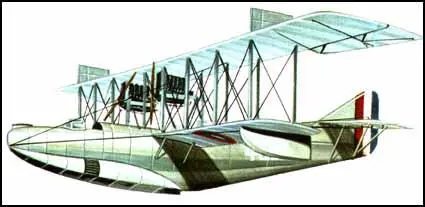

In January 1914 the government established the Royal Naval Air Service (RNAS). Within a few months the RNAS had 217 pilots and 95 aircraft (55 of them seaplanes). One of the most successful seaplanes purchased by the RNAS was the Curtiss H-16, a craft produced by Glen Hammond Curtiss in the USA.

By the outbreak of the First World War in August 1914, the RNAS had more aircraft under its control than the Royal Flying Corps. The main role of the RNAS was fleet reconnaissance, patrolling coasts for enemy ships and submarines, attacking enemy coastal territory and defending Britain from enemy air-raids. The leading war ace in the RNAS was Raymond Collishaw with 60 victories.

The RNAS was severely attacked for its failure to prevent the Zeppelin bombing raids. In February 1916 there was a change of policy and the Royal Flying Corps were given responsibility of dealing with Zeppelins once they were over Britain. The RNAS now concentrated on bombing Zeppelins on the ground in Germany.

The RNAS also had fighter squadrons on the Western Front. Popular aircraft with these pilots included the Bristol Scout, the Sopwith Pup and the Sopwith Camel.

When the RNAS had 67,000 officers and men, 2,949 aircraft, 103 airships and 126 coastal stations when it was decided to merge it with the Royal Flying Corps to form the Royal Air Force in April 1918.

Primary Sources

(1) Henry Allingham, Last Post (2005)

When we were flying off the ships, we couldn't stay airborne for long because we'd run out of fuel - that was the trouble. People sometimes had to ditch their aircraft. I saw about seven ditchings. Sometimes the plane would be going up steeply, then it would stop and start going back and it would have no speed - no power. The wind was stronger than the power it had to go forward. In about twelve months they were able to overcome that with a lot more power.

We never ditched - fortunately - because if you ditched you were in big trouble. We never had any parachutes and we didn't have radio. We had pigeons which we carried in a basket - but I never had to use them. Some of our people who were adrift in the drink could be there for up to five days, and they used to let the pigeons go. They would fly back to the loft at the station, and a search party would be sent out to look for them. As a general rule, after five days of searching, they'd give up and the men were lost.

However, I met a fellow once who was on leave from the Halcyon; he was sitting beside me one afternoon by the River Dee, and he said how he'd been lucky. He'd ditched and they were about to give up looking for him when somebody thought they saw something - and sure enough, it was him. He was very lucky.

In those days you had an open cockpit and it was very cold. You had a leather jacket and a leather helmet, and you'd put Vaseline on your face, and you had gloves to protect you from frostbite. The standard issue was long johns and you had a thick shirt and a vest. Over the top of that you had a grey shirt and a tunic. Your working gear was a tunic with patch pockets, which was very useful and practical. Then you had a choice - you could have trews or you could wear britches and puttees [strips of cloth wound around the leg to form leggings], which took a while to put on. With regard to equipment, you didn't have gun mountings in the aircraft until about June of 1916. That was when we first got the Lewis gun. When I first got in the cockpit, it was my job to sit behind the pilot and defend the plane with two Lee Enfield Rifles.

Once Lewis guns were mounted on our planes, we had the problem of trying to shoot through the propeller. in the air, if you tried it, you'd just shoot the prop away. Then they developed the synchromesh gear with the engine, which synchronised the firing of the machine gun through the prop. It was amazing. We made rapid progress in the last three months of 1916, and from then on we didn't really look back. They gave us the Bristol, Sopwith, Handley Page and so on, and aircraft producers have made good progress from then on. In 1917, they started putting radios in the aircraft. They could send signals over forty miles, so the radio fellows told me, and they could receive signals over sixty. From then on we didn't need the pigeons.

(2) London Gazette (May, 1917)

From 26 April to 6 May 1917 flying over France, Captain Ball took part in 26 combats in the course of which he destroyed 11 hostile aircraft, brought down two out of control and forced several others to land. Flying alone, on one occasion he fought six hostile machines, twice he fought five and once four. When leading two other British planes he attacked an enemy formation of eight - on each of these occasions he brought down at least one enemy plane, and several times his plane was badly damaged. On returning with a damaged plane he had always to be restrained from immediately going out in another.