Zeppelin Raids

Count Ferdinand Zeppelin, a German army officer, began developing his ideas on airships in 1897. The first Zeppelin flew on 2nd July 1900. The LZ-3 Zeppelin was accepted into army service in March 1909. By the start of the First World War the German Army had seven military Zeppelins.

The Zeppelin developed in 1914 could reach a maximum speed of 136 kph and reach a height of 4,250 metres. The Zeppelin had five machine-guns and could carry 2,000 kg (4,400 lbs) of bombs.

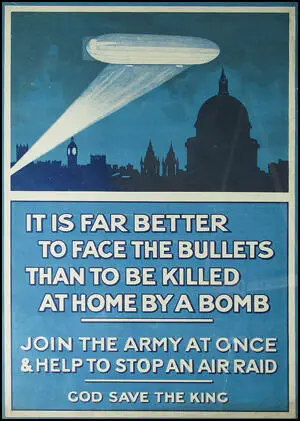

In January 1915, two Zeppelin navel airships 190 metres long, flew over the east coast of England and bombed great Yarmouth and King's Lynn. The first Zeppelin raid on London took place on 31st May 1915. The raid killed 28 people and injured 60 more.

Many places suffered from Zeppelin raids included Edinburgh, Gravesend, Sunderland, the Midlands and the Home Counties. By the end of May 1916 at least 550 British civilians had been killed by German Zeppelins.

Many places suffered from Zeppelin raids included Edinburgh, Gravesend, Sunderland, the Midlands and the Home Counties. By the end of May 1916 at least 550 British civilians had been killed by German Zeppelins.

Zeppelins could deliver successful long-range bombing attacks, but were extremely vulnerable to attack and bad weather. British fighter pilots and anti-aircraft gunners became very good at bringing down Zeppelins. A total of 115 Zeppelins were used by the German military, of which, 77 were either destroyed or so damaged they could not be used again. In June 1917 the German military stopped used Zeppelins for bombing raids over Britain.

Primary Sources

(1) Joaqchim Breithaupt was the commander of the L15 Zeppelin that bombed London on 13th October, 1915.

On board were two warrant officers and twelve ratings. The total weight-carrying capacity of the ship, including barometers, temperature and humidity measuring appliances and also the specific weight of the gas was about 30,800 pounds. At this weight the petrol comprised about 11,000 pounds, and bombs 3,410 pounds (28 explosive bombs of 1110 pounds each and 15 incendiary bombs of 22 pounds each.

At 1930 hours we were between Cromer and Great Yarmouth at a height of 6,500 feet. The visibility was good under a starlit sky. We took our bearings, waited for full darkness, and then steered a direct course for our objective - London. As we crossed over the coast we came under sharp fire from the batteries, and the ships were lit up by the searchlights of the coastguard and shore batteries.

At 1930 hours we were between Cromer and Great Yarmouth at a height of 6,500 feet. The visibility was good under a starlit sky. We took our bearings, waited for full darkness, and then steered a direct course for our objective - London. As we crossed over the coast we came under sharp fire from the batteries, and the ships were lit up by the searchlights of the coastguard and shore batteries.

As we flew over the land we checked our position from time to time by dropping light bombs. At about 2130 hours the Thames, with its characteristic windings, was clearly distinguishable below us. Suddenly, from all sides, searchlights leaped out towards us, and as we flew over Tottenham a wild barrage from the anti-aircraft positions began. The shells burst at a good height right in our course. I therefore rose, after dropping three explosive bombs.

We then steered over Hyde Park, in the direction of the City. The picture we saw was indescribably beautiful - shrapnel bursting all around, our own bombs bursting and the flashes from the anti-aircraft batteries below. We flew over the City at between 9,000 and 9,800 feet and dropped twenty 110-pound bombs, and all the incendiary bombs. We could see large explosions between Charing Cross Station and the Bank of England.

(2) While on leave from from France William Brooks and his girlfriend witnessed a Zeppelin raid on London.

One night, we watched a Zeppelin raid on the Woolwich Aresnal. The German Zeppelin was sort of hovering over the building dropping bombs and they scored a couple of direct hits, causing massive explosions. We felt the blast two to three miles away. A few small bi-planes of ours went up to attack it but the Zeppelin had heavy machine-guns mounted in the cabin slung beneath it and, being almost stationary, could take careful aim on a plane. So our brave airman stood no chance. But one little plane went up, one of those double wing ones with all the struts holding the wings together. Well, this pilot flew above the Zeppelin and dropped bombs onto it. One hit it square on - flames started to light up the night sky. She was on fire all right. Everyone in the street started to cheer.

My dad was watching through a small telescope he had and said he could see the men on the Zeppelin inside the cabin rushing about throwing ropes over the side, and other things, trying to lighten the ship. Anyway, its main engines started up with a roar and she slowly began to move away with smoke pouring out of her. Well, dad said they knew they were done for, but were going to try and make it home. As it pulled away it looked like a huge wounded animal and going to die. It crashed in flames over Essex before it made the Channel. I know they were our enemies but I couldn't feel sorry for them. That was the last of the Zeppelin raid. They proved too vulnerable.

The pilot of our small plane was a Lt. Robinson and he got the Victoria Cross for that, but the poor man was shot down and killed over France a year later by an ace German fighter-pilot.

Note: (Brookes was incorrect concerning his fate. Although he was shot down over France by a German ace (one of the Red Barons wing men) he survived the war and died in the massive flu outbreak just after the war ended.

(3) On 26th August 1916, Margaret McMillan and her sister Rachel, experienced a Zeppelin bombing raid in London.

Looking out from my bedroom window, we saw something bright and sparkling in the sky.

"What can it be? I said to Rachel.

She looked at it steadily. "A Zeppelin"

Two or three of our friends ran upstairs to warn us. "It's a Zeppelin dropping bombs, or going to." We all gazed at it if fascinated.

A terrific blast struck the house as we went downstairs. I looked up and saw that Rachel had not followed us. In the same moment, an awful explosion shook the little house to its foundations. I called, and she appeared on the last landing carrying blankets. She had just time to join us when a third crash sent all our windows in, and the ironwork along the outer wall, which served as a ventilator for the lower room.

(4) David Kirkwood, a trade union leader, was in Edinburgh in 1916 during a Zeppelin air raid. He wrote about it in his autobiography, My Life of Revolt (1935)

Suddenly a terrifying explosion occurred. Windows rattled, the ground quivered, pictures swung. We all gasped. I ran to the window and saw Vesuvius in eruption.

As I watched, I felt myself alone. Turning round, I found that my companions had run out of the house, even without putting on their boots. The door opened and the old lady appeared in a dressing-gown. At that moment another terrific explosion shook us. She said : " Oh, dear, I do hope the noise won't waken Sonnie ! "

I could not help smiling at her courage and care.

" It's probably all over now," I said.

She replied, " I hope so," and went off to bed again.

I opened the window. A great flash greeted me from the Castle and then, above the roaring, I heard the most dreadful screeching and shouting. The inmates in the Morningside Asylum had started pandemonium.

(5) on 2nd August, 1916, Sir John French arranged for Charles Repington to see how the War Office was dealing with Zeppelin air raids.

About 10.30 p.m. came the news over the telephone of the imminence of a fresh Zeppelin raid. We all went off, and I had an opportunity of seeing the whole of the anti-Zeppelin arrangements working at full pressure in the stables, or cellars, at a certain place. General Shaw was there in control of a Staff of about twenty or thirty young officers, naval and military, clerks, telegraph and telephone and wireless operators, etc. The telephonic and telegraphic system very complete, and messages came in with few delays.

I went first to the Chart Room, where the position of most if not all the Zeppelins in the North Sea before the raid began was shown. This is done in the following manner: Zeppelins cannot navigate at night with any certainty of knowing where they are. They, therefore, send by wireless to Germany the number of their ship - L29, or whatever it is - and two German wireless stations, at a wide distance apart, get the message and send it back at once the exact bearing of the airship, which they can do by one of the many inventions of this art. The airship officer plots the two bearings, the intersection of which then gives him his position. But we also pick up the airship's number, and, by cross bearings from our wireless stations, can plot in the Chart Room the exact position of every Zeppelin.