On this day on 2nd November

On this day in 1470 Edward V of England is born. He was the eldest son of Edward IV and Elizabeth Woodville, was born in 1471. Edward was trained to become king but was only a child when his father died in 1483. It was therefore decided that Richard, Edward IV's brother, should became Protector of England, until Edward was old enough to become king.

Elizabeth Woodville did not trust Richard and called for a Regency Council to run the country. Richard reacted by persuading Parliament that Edward IV had not been legally married to Elizabeth Woodville, and therefore Prince Edward was not the true heir to the throne. As Edward IV's only surviving brother, Richard claimed the throne for himself. Richard had Edward and his younger brother, Richard, taken into custody. Soon rumours began to circulate that Richard had arranged for his two nephews to be murdered.

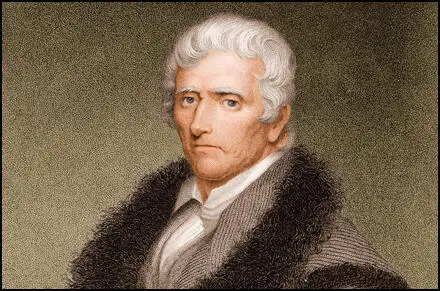

On this day in 1734 Daniel Boone, American explorer ?was born. His family migrated to North Carolina in 1750 and established a farm by the Yadkin Valley. As soon as he was old enough he became an animal hunter. Boone joined the expedition led by Major General Edward Braddock as a blacksmith and teamster. He was with Braddock when he was killed on 13th July, 1755.

In 1767 Boone and two companions explored Kentucky. Impressed with what he found he led a party of migrant families from North Carolina to Kentucky in September, 1773. Working for Richard Henderson and his Transylvania Company, Boone helped lay out the Wilderness Road. He also explored the Cumberland Gap of the Appalachian Mountains. He was also involved in the establishment of the Boonesborough Fort on the Kentucky River.

Boone was captured by Shawnees in 1778 and was taken to Detroit but managed to escape. He returned to Boonesborough where he organized the settlers in defending the town from an Indian attack. Over the next few years Boone served as a sheriff of Boonesborough. He also worked as a surveyor.

In 1799 Boone moved to Missouri and in 1814 Congress granted him 850 acres in the area. Boone was forced to sell the land in order to pay his considerable debts incurred while he was in Kentucky. Boone continued to hunt and trap animals until his early eighties. Daniel Boone died in St. Charles County, Missouri, on 26th September, 1820.

On this day in 1781 Anne Knight, the daughter of third of the eight children of wholesale grocer, William Knight (1786–1862), was born in Chelmsford. Anne's mother was Priscilla Allen Knight (1753–1829), the daughter of William Allen, a well-known radical and Nonconformist. The Knight family were members of the Society of Friends and were pacifists and social reformers.

Anne became active in the struggle against slavery and became a close friend of Elizabeth Heyrick and during the early 1820s sent each other pamphlets on social reform. They both favoured immediate rather than gradual abolition of the slave-trade.

In 1824 Heyrick published her pamphlet Immediate not Gradual Abolition. In her pamphlet Heyrick argued passionately in favour of the immediate emancipation of the slaves in the British colonies. This differed from the official policy of the Anti-Slavery Society that believed in gradual abolition. She called this "the very masterpiece of satanic policy" and called for a boycott of the sugar produced on slave plantations.

In the pamphlet Heyrick attacked the "slow, cautious, accommodating measures" of the leaders. "The perpetuation of slavery in our West India colonies is not an abstract question, to be settled between the government and the planters; it is one in which we are all implicated, we are all guilty of supporting and perpetuating slavery. The West Indian planter and the people of this country stand in the same moral relation to each other as the thief and receiver of stolen goods".

The leadership of the organisation attempted to suppress information about the existence of this pamphlet and William Wilberforce gave out instructions for leaders of the movement not to speak at women's anti-slavery societies. His biographer, William Hague, claims that Wilberforce was unable to adjust to the idea of women becoming involved in politics "occurring as this did nearly a century before women would be given the vote in Britain".

George Stephen disagreed with Wilberforce on this issue and claimed that their energy was vital in the success of the movement: "Ladies Associations did everything... They circulated publications; they procured the money to publish; they talked, coaxed and lectured: they got up public meetings and filled our halls and platforms when the day arrived; they carried round petitions and enforced the duty of signing them... In a word they formed the cement of the whole anti-slavery building - without their aid we never should have kept standing."

On 8th April, 1825, Lucy Townsend held a meeting at her home to discuss the issue of the role of women in the anti-slavery movement. Townsend, Elizabeth Heyrick, Mary Lloyd, Sarah Wedgwood, Sophia Sturge and the other women at the meeting decided to form the Birmingham Ladies Society for the Relief of Negro Slaves (later the group changed its name to the Female Society for Birmingham). The group "promoted the sugar boycott, targeting shops as well as shoppers, visiting thousands of homes and distributing pamphlets, calling meetings and drawing petitions."

The society which was, from its foundation, independent of both the national Anti-Slavery Society and of the local men's anti-slavery society. As Clare Midgley has pointed out: "It acted as the hub of a developing national network of female anti-slavery societies, rather than as a local auxiliary. It also had important international connections, and publicity on its activities in Benjamin Lundy's abolitionist periodical The Genius of Universal Emancipation influenced the formation of the first female anti-slavery societies in America".

Anne Knight was inspired by the Birmingham Ladies Society for the Relief of Negro Slaves for form a similar organisation in Chelmsford. Other groups were established in Nottingham (Ann Taylor Gilbert), Sheffield (Mary Anne Rawson, Mary Roberts), Leicester (Elizabeth Heyrick, Susanna Watts), Glasgow (Jane Smeal), Norwich (Amelia Opie, Anna Gurney), London (Mary Anne Schimmelpenninck, Mary Foster) and Darlington (Elizabeth Pease). By 1831 there were seventy-three of these women's organisations campaigning against slavery.

In early 1833 Anne Knight joined forces with the London Female Anti-Slavery Society to organise a national women's petition against slavery. When it was presented to Parliament it was signed by 298,785 women. It was the largest single anti-slavery petition in the movement's history.

The Slavery Abolition Act was passed on 28th August 1833. This act gave all slaves in the British Empire their freedom. The British government paid £20 million in compensation to the slave owners. The amount that the plantation owners received depended on the number of slaves that they had. For example, Henry Phillpotts, the Bishop of Exeter, received £12,700 for the 665 slaves he owned.

In 1834 Anne Knight toured France where she gave lectures on the immorality of slavery. Knight argued for the immediate abolition of slavery without compensation in the rest of Europe. Later, her contribution to the anti-slavery campaign was recognised when a village for Jamaican freed slaves was named Knightsville. She was also active in the British and Foreign Anti-Slavery Society.

Anne Knight attended the World Anti-Slavery Convention held at Exeter Hall in London, in June 1840 but as a woman was refused permission to speak. She did meet two American delegates Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Lucretia Mott. Stanton later recalled: "We resolved to hold a convention as soon as we returned home, and form a society to advocate the rights of women." Mott described Knight as "a singular-looking woman - very pleasant and polite".

She became aware that the artist, Benjamin Robert Haydon, had started a group portrait of those involved in the fight against slavery. She wrote a letter to Lucy Townsend complaining about the lack of women in the painting. "I am very anxious that the historical picture now in the hand of Haydon should not be performed without the chief lady of the history being there in justice to history and posterity the person who established (women's anti-slavery groups). You have as much right to be there as Thomas Clarkson himself, nay perhaps more, his achievement was in the slave trade; thine was slavery itself the pervading movement."

When the painting was completed it did not include Lucy Townsend or most of the leading female campaigners against slavery. Clare Midgley, the author of Women Against Slavery (1995) points out that as well as Anne Knight and Lucretia Mott, it does feature Elizabeth Pease, Mary Anne Rawson, Amelia Opie and Annabella Byron: "Haydon's group portrait is exceptional in that it does record the existence of women campaigners. Most other memorials did not. There are no public monuments to women activists to complement those to William Wilberforce, Thomas Clarkson and other male leaders of the movement... In the written memoirs of these men, women tend to appear as helpful and inspirational wives, mothers and daughters rather than as activists in their own right."

Marion Reid published A Plea for Women in 1843. Knight was grateful that she had stated the case for greater equality but thought that the author had unestimated the abilities of women. Knight wrote on her own copy of the book that it was "excellent with the exception of the great folly" where she said that women faced natural barriers. Knight complained that women did not have natural barriers "but those placed equally before men."

The behaviour of the male leaders at the World Anti-Slavery Convention inspired Knight to start a campaign advocating equal rights for women. This included having gummed labels printed with feminist quotations that she attached to the outside of her letters. In 1847 she wrote a letter to Matilda Ashurst Biggs on the subject of gender equality. Later that year the letter was published and it is considered to be the first ever leaflet on women's suffrage.

Knight wrote: "I wish the talented philanthropists in England would come forward in this critical juncture of our nation's affairs and insist on the right of suffrage for all men and women unstained with crime... in order that all may have a voice in the affairs of their country... Never will the nations of the earth be well governed until both sexes, as well as all parties, are fully represented, and have an influence, a voice, and a hand in the enactment and administration of the laws."

Knight also became active in the Chartist movement. However, she became concerned about the way women campaigners were treated by some of the male leaders in the organisation. She criticised them for claiming "that the class struggle took precedence over that for women's rights". Knight wrote "can a man be free, if a woman be a slave." In a letter published in the Brighton Herald in 1850 she demanded that the Chartists should campaign for what she described as "true universal suffrage".

An anonymous leaflet was published in 1847. It has been persuasively argued that the author of the work was Anne Knight. In argued: "Never will the nations of the earth be well governed, until both sexes, as well as all parties, are fully represented and have an influence, a voice, and a hand in the enactment and administration of the laws".

Knight also became involved in international politics. In 1848 she was the first French government elected by universal manhood suffrage repressed freedom of association. The decree prohibited women from forming clubs or attending meetings of associations. Knight published a pamphlet criticising this action: "Alas, my brother, is it then true that thy eloquent voice has been heard in the heart of the National Assembly expressing a sentiment so contrary to real republicanism? Can it be that thou hast really protested not only against women's rights to form clubs but also against their right to attend clubs formed by men?"

At a conference on world peace held in 1849, Anne Knight met two of Britain's reformers, Henry Brougham and Richard Cobden. She was disappointed by their lack of enthusiasm for women's rights. For the next few months she sent them several letters arguing the case for women's suffrage. In one letter to Cobden she argued that it was only when women had the vote that the electorate would be able to pressurize politicians into achieving world peace.

Anne Knight and Anne Kent established the Sheffield Female Political Association. Their first meeting was held in Sheffield in February, 1851. Later that year it published an "Address to the Women of England". This was the first petition in England that demanded women's suffrage. It was presented to the House of Lords by George Howard, 7th Earl of Carlisle. (27) The following year she was "forbidden to vote for the man who inflicts the laws I am compelled to obey - the taxes I am compelled to pay". She added that "taxation without representation is tyranny".

Anne Knight, who never married, spent the last few years of her life in Waldersbach, a small village south-west of Strasbourg, where she lived in the former home of pastor Jean-Frédéric Oberlin (1740-1826), the founder of the Christian Socialist movement in France and a man she greatly admired. Anne Knight died on 4th November, 1862.

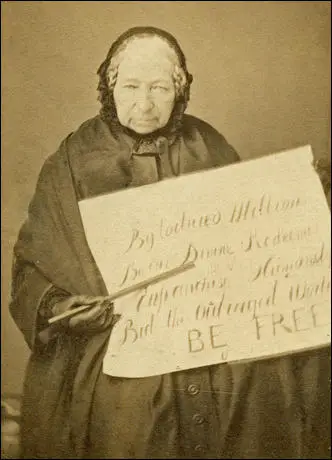

placard reads: "By tortured millions, By the Divine Redeemer,

Enfranchise Humanity, Bid the Outraged World, BE FREE".

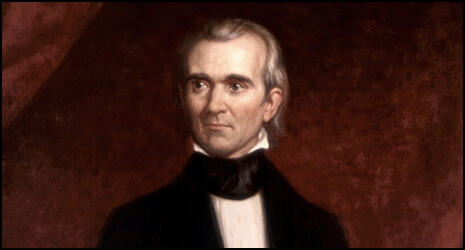

On this day in 1795 James K. Polk, was born in Mecklenburg, North Carolina. When Polk was a child the family moved to Tennessee. Although he suffered from poor health, Polk managed to attend and graduate from the University of North Carolina. Polk was admitted to the bar in 1820 and practiced law in Nashville. A member of the Democratic Party, Polk was elected to Congress in 1825 and became house speaker ten years later. In 1839 Polk was elected governor of Tennessee.

In 1843 Martin Van Buren was expected to become the Democratic Party candidate in the presidential election. However, Polk won the nomination and beat Henry Clay (Whig Party) and James Birney (Liberty Party) in the election.

In December, 1845, Polk announced the annexation of Texas. This marked the beginning of the Mexican War and Zachary Taylor and a 4,000 man army, was ordered into the Rio Grande. Taylor defeated the Mexicans at Palo Alto on 8th May, 1846 and in September captured Monterrey. Taylor upset Polk when he granted the Mexican Army an eight-week armistice. Polk took away Taylor's best troops and ordered him to fight a defensive war. Taylor disobeyed these orders and in February, 1847, marched south and although outnumbered four to one, defeated the Mexican Army at Buena Vista.

In 1848 the Whig Party selected Zachary Taylor as its candidate for president. Polk decided not to stand and the Democratic Party candidate, Lewis Cass (1,220,544), was defeated by Taylor. James Polk died soon afterwards in Nashville, Tennessee, on 15th June, 1849.

On this day in 1874 Rudolf Breitscheild, the son of a bookseller, was born in Cologne, Germany, was born. After studying political economy at the University of Munich and the University of Marburg he entered journalism and eventually became editor of a left-wing newspaper in Hamburg. Breitscheild joined the Social Democratic Party (SDP) and was elected to the Berlin town council in 1904. Over the next few years he emerged as one of the leaders of the party.

Karl Liebknecht was the only member of the Reichstag who voted against Germany's participation in the First World War. He argued: "This war, which none of the peoples involved desired, was not started for the benefit of the German or of any other people. It is an Imperialist war, a war for capitalist domination of the world markets and for the political domination of the important countries in the interest of industrial and financial capitalism. Arising out of the armament race, it is a preventative war provoked by the German and Austrian war parties in the obscurity of semi-absolutism and of secret diplomacy."

Friedrich Ebert, the leader of the Social Democratic Party, initially opposed to the idea of the country going to war. However, once the First World War had started, he ordered the SDP members in the Reichstag to support the war effort. Ebert called for a defensive, rather than an offensive war. With the formation of the Third Supreme Command, in August, 1916, Ebert's political power was undermined.

Breitscheild began questioning the policies of Ebert and in April 1917, along with other left-wing figures in the party formed the Independent Socialist Party. Other members of the ISP included Kurt Eisner, Karl Kautsky, Eduard Bernstein, Julius Leber and Rudolf Hilferding. After the German Revolution in Prussia in 1918 he briefly became Minister of the Interior in the new government. Raymond Gram Swing of the Chicago Daily News, commented: "My best friend among the new leaders was Rudolph Breitscheid, head of the Independent Socialists, a tall, narrow-shouldered man, a little stooped, who to me personified the hopes and virtues latent in the Weimar Republic."

In 1922 Breitscheild returned to the Social Democratic Party and supported the government of Hermann Muller between 1928 and 1930. With the growth of the Nazi Party Breitscheild argued for a protective alliance between the SDP and the German Communist Party (KPD).

When Adolf Hitler gained power Breitscheild was forced to flee to France and in 1938 helped to form the Central Union of German Emigrants. When the German Army invaded France in 1940 Breitscheild fled to Marseilles. However, in 1941 he was arrested by the Vichy government and handed over to the Gestapo.

Rudolf Breitscheild was sent to Buchenwald Concentration Camp. According to the Völkischer Beobachter, Breitscheid, along with Ernst Thälmann, was killed during an Allied air raid on 28th August, 1944. However, it is believed that Breitscheild was executed with Thälmann on 24th of that month.

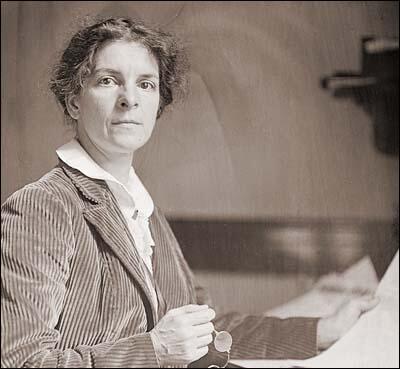

On this day in 1866 Rheta Childe Dorr was born in Omaha. After graduating from the University of Nebraska she moved to New York City in 1890 and eventually found work with the New York Evening Post.

A supporter of women's suffrage, Dorr wrote a great deal about the reform movement. This included the campaign to end child labour and an improvement in trade union rights. She was also a regular contributor to Hampton's Magazine and soon established her as a leading muckraker journalist. In 1910 a collection of her articles, What Eight Million Women Want, was published. The book was very successful and sold over half a million copies.

In 1912 Dorr travelled to Europe where she interviewed leading figures in the suffrage movement. She met Emmeline Pankhurst and became a strong supporter of the kind of direct action favoured by the Women Social & Political Union.

On her return to the United States Dorr joined the Congressional Union for Woman Suffrage and became the first editor of its journal, The Suffragist. Like the leaders of the Women Social & Political Union, Dorr supported participation in the First World War. This alienated from her former reform friends, many of whom worked for the Woman's Peace Party.

Rheta Childe Dorr died on 8th August 1948.

On this day in 1903 Hope Hale Davis was born. On 18th February 1932 Hope Hale married the British journalist, Claud Cockburn. At the time he was working for The Times. However, the Great Depression had a dramatic impact on Cockburn's political opinions. He now considered himself a Marxist. Hope later wrote of Cockburn: "I wanted what a woman has traditionally asked of a lover going off to war - his qualities and his heritage." She was attracted to him for his "charm, gaiety, mischief and wit" and the way he made people laugh. But privately with her, she added, he would talk seriously about how "we could sweep away all these disgraces at once and build a new society that would rule them out forever". (6) Hope gave birth to Claudia Cockburn but the marriage did not last.

In 1934 Hope Hale divorced Claud Cockburn and married Karl Hermann Brunck. The same year, they both joined the Communist Party of the United States (CPUSA). They were invited to the home of Charles Kramer, for their first meeting. Also in attendance were Mildred Kramer, Victor Perlo and Marion Bachrach. Kramer explained that the CPUSA was organized in units. "Charles... explained that... we would try to limit our knowledge of other members, in case of interrogation, possible torture. Such an idea, he admitted, might seem rather remote in the radical Washington climate, but climates could change fast. In most places members of units knew each other only by their Party pseudonyms, so as not to be able to give real names if questioned."

Kramer also told the group that in future they should obtain their copies of the Daily Worker and the New Masses from him instead of newsstands. "We must keep away from any place where leftists might gather. We must avoid, as far as possible, associating with radicals, difficult as that would be in Washington." Even outspoken liberals such as Jerome Frank and Gardner Jackson "were out of bounds". Kramer added "we couldn't go near any public protests or rallies."

Hope Hale met Harold Ware who was a consultant to the AAA. She described Ware as having a voice that was "always easy sounding, unlike the staccato of most Party men" and was reassured by Ware's "tanned lean face, his rolled-up blue shirt sleeves showing the muscles in his forearms". Hope joined Ware's "discussion group" that included Charles Kramer, Alger Hiss, Nathaniel Weyl, John Abt, Laurence Duggan, Harry Dexter White, Abraham George Silverman, Nathan Witt, Marion Bachrach, Julian Wadleigh, Henry H. Collins, Lee Pressman, Charles Kramer and Victor Perlo. Ware was working very close with Joszef Peter, the "head of the underground section of the American Communist Party." It was claimed that Peter's design for the group of government agencies, to "influence policy at several levels" as their careers progressed". Weyl later recalled that every member of the Ware Group was also a member of the CPUSA: "No outsider or fellow traveller was ever admitted... I found the secrecy uncomfortable and disquieting."

Hope Hale returned to New York City in 1939 where she worked as a free-lance writer. She married literary critic Robert Gorham Davis later that year. They both left the Communist Party of the United States (CPUSA) after the signing of the Nazi-Soviet Pact. "We who were self-blinded suffer the further pain of shame. Not shame that we joined in the fight, which indeed must be renewed and renewed, as long as people are still ill-fed, ill-clothed, ill-housed, and brutally tortured. My shame is in the terms of my joining: I forfeited my most essential freedom, to think for myself. Instead of keeping my wits about me, I gave them over to others, believing big lies and rejecting truths as big as millions starving. No excuse can lighten the knowledge that I used my brain and talents in defense of Stalin."

On this day in 1917 Emmeline Pankhurst and Christabel Pankhurst changed the name of the Women's Social and Political Union to the Women's Party. Its twelve-point programme included: (a) A fight to the finish with Germany. (b) More vigorous war measures to include drastic food rationing, more communal kitchens to reduce waste, and the closing down of nonessential industries to release labour for work on the land and in the factories. (c) A clean sweep of all officials of enemy blood or connections from Government departments. Stringent peace terms to include the dismemberment of the Hapsburg Empire."

The Women's Party also supported: "equal pay for equal work, equal marriage and divorce laws, the same rights over children for both parents, equality of rights and opportunities in public service, and a system of maternity benefits." Christabel and Emmeline had now completely abandoned their earlier socialist beliefs and advocated policies such as the abolition of the trade unions.

David Lloyd George commented to Andrew Bonar Law, that the Women's Party had been very useful in the fight against the Labour Party: "The Women's Party... has been extremely useful, as you know, to the Government especially in the industrial districts where there has been trouble during the last two years. They have fought the Bolshevik and Pacifist element with great skill, tenacity and courage."

Christabel Pankhurst became one of the seventeen women candidates that stood in the 1918 General Election. She was the only candidate of the Women's Party. She contested Smethwick, and the Conservative Party candidate agreed to stand down so it could be a straight fight with the Labour Party. Her alliance with the Conservatives brought her into conflict with Sylvia Pankhurst, who was a committed socialist.

Christabel accused the Labour candidate, John E. Davidson, of being a Bolshevik. Davidson replied that far from being "corrupted and led by Bolshevists' the Labour Party stood for social reform along constitutional lines "without breaking a single window, firing a single pillar-box, or burning down a single church." Davidson beat Pankhurst by 775 votes.

Christabel Pankhurst was very disappointed by the this result and brought an end to the Women's Party in June 1919, and she and her mother joined the Conservative Party. As Melanie Phillips pointed out: "Mrs Pankhurst and Christabel, it turned out, would have no part to play in the long agitation ahead for equality of franchise, pay, opportunity, divorce and inheritance."

On this day in 1926 women's suffrage campaigner Anne Cobden Sanderson died at 15 Upper Mall, Hammersmith

Anne Cobden, the fourth daughter of Richard Cobden, was born on 26 March 1853 at Westbourne Terrace, London. Her early years were spent at Dunford House, Midhurst, but after her father's death in 1865 she finished her education in Germany.

A supporter of women's rights she attended the Women's Suffrage Conference held in London in April 1871. Soon afterwards she joined the London Society for Women's Suffrage.

During this period she became friends with other suffragists such as Helen Taylor, Millicent Garrett, Elizabeth Garrett, Barbara Bodichon, Jessie Boucherett, Emily Davies, Francis Mary Buss, Dorothea Beale, Anne Clough, Elizabeth Wolstenholme-Elmy, Louisa Smith, Alice Westlake, Katherine Hare and Harriet Cook.

In 1874 with her sister Ellen she accompanied Sir Robert Lambert Playfair on his expedition to the Aures Mountains, Algeria. In 1877 she lived in London with her sisters and became involved in social work in the East End.

Anne Cobden married the barrister Thomas James Sanderson on 5th August 1882. They both held progressive political opinions and adopted the surname Cobden-Sanderson. Anne had two children, Richard (1884–1964) and Stella (1886–1979). She became good friends with William Morris and was influenced by the economic ideas of Henry George. Anne Cobden-Sanderson became a socialist and in 1890 joined Morris's Hammersmith Socialist Society. Anne and Thomas established the Doves Press and this became an important part of the Arts and Crafts Movement.

Anne eventually joined the Independent Labour Party and in 1902 organized a series of lectures for the ILP. She continued with her social work and supported Margaret MacMillan and Rachel MacMillan and their pioneering Bow Children's Clinic. The clinic provided dental help, surgical aid and lessons in breathing and posture. Anne and the MacMillan sisters also campaigned for school meals and compulsory medical inspection.

For several years Anne Cobden Sanderson was a member of the National Union of Women's Suffrage Societies. However, frustrated by its lack of success, she joined the Women Social & Political Union in 1905. She was the first prominent constitutional suffragist to defect to the militants. In October 1906 Anne, along with members of the WSPU, Mary Gawthorpe, Charlotte Despard and Emmeline Pankhurst, was arrested in a large demonstration outside the House of Commons. Her friend, George Bernard Shaw wrote in The Times, that "one of nicest women in England suffering from the coarsest indignity" of being in Holloway Prison.

In court Anne said: "We have talked so much for the Cause now let us suffer for it... I am a law breaker because I want to be a law maker." She was sentenced to two months' imprisonment. Millicent Fawcett wrote to The Times on 27th October 1906 to complain about the press reports of her behaviour in court: "I have known Mrs Cobden Sanderson for 30 years. I was not in the police-court on Wednesday when she was before the magistrate, but I find it absolutely impossible to believe that she bit, or scratched, or screamed, or behaved otherwise than like the refined lady she is." After Sanderson's release the NUWSS organized a banquet at the Savoy Hotel on 11th December. Those who attended included Beatrice Harraden, Minnie Baldock and Annie Kenney at the banquet.

In 1907 some leading members of the WSPU began to question the leadership of Emmeline Pankhurst and Christabel Pankhurst. These women objected to the way that the Pankhursts were making decisions without consulting members. Teresa Billington-Greig pointed out the absurdity of women fighting for votes in an organisation that refused them a voice in their own campaign. In the autumn of 1907, Anne Cobden Sanderson, Teresa Billington-Greig, Elizabeth How-Martyn, Dora Marsden, Helena Normanton, Anne Cobden Sanderson, Margaret Nevinson and Charlotte Despard and seventy other members of the WSPU left to form the Women's Freedom League (WFL).

According to Elizabeth Crawford, the author of The Suffragette Movement (1999): "Anne Cobden Sanderson proved one of the WFL's most tireless campaigners, speaking at outdoor meetings and continuing to take part in militant protests." She was arrested on 19th August 1909 while picketing the door of 10 Downing Street in order to present a petition to Herbert Asquith.

In October 1909 Anne Cobden Sanderson helped establish the Tax Resistance League (TRL). Founder members of the organisation included Louisa Garrett Anderson, Margaret Nevinson, Cicely Hamilton, Edith How-Martyn, Sime Seruya, Maud Arncliffe Sennett, Lena Ashwell, Dora Montefiore, Beatrice Harraden, Evelyn Sharp and Eveline Haverfield. The TRL remained under the auspices of the Women's Freedom League. The motto adopted by the TRL was "No Vote No Tax".

At its annual party conference in January 1912, the Labour Party passed a resolution committing itself to supporting women's suffrage. This was reflected in the fact that all Labour MPs voted for the measure at a debate in the House of Commons on 28th March. Soon afterwards Henry N. Brailsford and Kathleen Courtney, entered negotiations with the Labour Party as representatives of NUWSS.

In April 1912, the National Union of Women's Suffrage Societies announced that it intended to support Labour Party candidates in parliamentary by-elections.The NUWSS established an Election Fighting Fund (EFF) to support these Labour candidates. Anne Cobden Sanderson, who had been a long-time supporter of the Labour Party, contributed generously to the EEF.

In July 1914 the NUWSS argued that Asquith's government should do everything possible to avoid a European war. Two days after the British government declared war on Germany on 4th August 1914, Millicent Fawcett declared that it was suspending all political activity until the conflict was over. Although the NUWSS supported the war effort, it did not follow the WSPU strategy of becoming involved in persuading young men to join the armed forces.

Despite pressure from members of the NUWSS, Fawcett refused to argue against the First World War. Her biographer, Ray Strachey, argued: "She stood like a rock in their path, opposing herself with all the great weight of her personal popularity and prestige to their use of the machinery and name of the union." At a Council meeting of the National Union of Women's Suffrage Societies held in February 1915, Fawcett attacked the peace efforts of people like Mary Sheepshanks. Fawcett argued that until the German armies had been driven out of France and Belgium: "I believe it is akin to treason to talk of peace." Anne Cobden Sanderson was a pacifist and was once again in opposition to Fawcett.

In January 1915 Mary Sheepshanks published an open Christmas letter to the women of Germany and Austria, signed by 100 British women pacifists. The signatories included Anne Cobden Sanderson, Emily Hobhouse, Margaret Bondfield, Maude Royden, Sylvia Pankhurst, Eva Gore-Booth, Margaret Llewelyn Davies and Marion Phillips. It included the following: "Do not let us forget our very anguish unites us, that we are passing together through the same experiences of pain and grief. We pray you to believe that come what may we hold to our faith in peace and goodwill between nations."

After the war Anne Cobden Sanderson remained active in the Labour Party in Hammersmith. Her husband, Thomas James Sanderson, died in 1922. As her biographer, A. C. Howe, pointed out: "Following Thomas's death in 1922, Annie settled at great personal cost a lawsuit brought against her by Sir Emery Walker, seeking compensation for the typeface her husband had thrown into the Thames on closing the Doves Press in 1917."

On this day in 1950 George Bernard Shaw died. In 1882 Shaw heard Henry George lecture on land nationalization. This had a profound effect on Shaw and helped to develop his ideas on socialism. Shaw now joined the Social Democratic Federation and its leader, H. H. Hyndman, introduced him to the works of Karl Marx. Shaw was convinced by the economic theories in Das Kapital but was aware that it would have little impact on the working class. He later wrote that although the book had been written for the working man, "Marx never got hold of him for a moment. It was the revolting sons of the bourgeois itself - Lassalle, Marx, Liebknecht, Morris, Hyndman, Bax, all like myself, crossed with squirearchy - that painted the flag red. The middle and upper classes are the revolutionary element in society; the proletariat is the conservative element."

Shaw became an active member of the Social Democratic Federation (SDF), and became friends with others in the movement including William Morris, Eleanor Marx, Annie Besant, Walter Crane, Edward Aveling and Belfort Bax. In May 1884 Shaw joined the Fabian Society and the following year, the Socialist League, an organisation that had been formed by Morris and Marx after a dispute with H. H. Hyndman, the leader of the SDF. Shaw gave lectures on socialism on street corners and helped distribute political literature. On 13th November he took part in a demonstration in London that resulted in the Bloody Sunday Riot. However, he always felt uncomfortable with trade union members and preferred debate to action.

By 1886, Shaw tended to concentrate his efforts on the work that he did with the Fabian Society. The society that included Edward Carpenter, Annie Besant, Walter Crane, Sidney Webb and Beatrice Webb believed that capitalism had created an unjust and inefficient society. They agreed that the ultimate aim of the group should be to reconstruct "society in accordance with the highest moral possibilities". As Shaw pointed out: "Some men see things as they are and say why. I dream things that never were and say why not."

On this day in 1957, the New Statesman published an article by J. B. Priestley that attacked the decision by Aneurin Bevan to abandon his policy of unilateral nuclear disarmament. The article resulted in a large number of people writing letters to the journal supporting Priestley's views. As Canon John Collins pointed out: "Whether other events may have contributed to the emergence of CND, J. B. Priestley's article exposing the utter folly and wickedness of the whole nuclear strategy was the real catalyst."

Kingsley Martin, the editor of the New Statesman, organised a meeting of people inspired by Priestley and as result they formed the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament (CND). Early members of this group included J. B. Priestley, Bertrand Russell, Fenner Brockway, Wilfred Wellock, Ernest Bader, Frank Allaun, Donald Soper, Vera Brittain, E. P. Thompson, Sydney Silverman, James Cameron, Jennie Lee, Victor Gollancz, Konni Zilliacus, Richard Acland, Stuart Hall, Ralph Miliband, Frank Cousins, A. J. P. Taylor, Canon John Collins and Michael Foot.

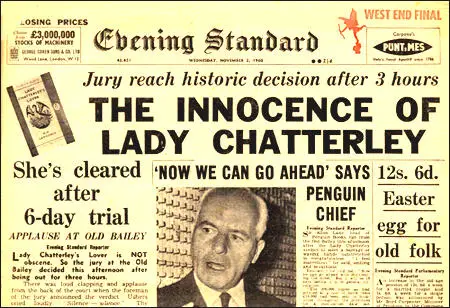

On this day in 1960 Penguin Books is found not guilty of obscenity in the trial against Lady Chatterley's Lover. In 1926 D. H. Lawrence visited Nottingham. This inspired him to begin a new novel. Lawrence's biographer, John Worthen, has argued: "His sympathy was now far more with his father (who had died in 1924) than with his mother, and the novel's central character was thoroughly working-class. The second version, started in November 1926, made the novel sexually explicit; it became a hymn to the love-making of the couple, to the body of the man and the woman, for sexuality as it could potentially be between an independent working-class man and an independent upper-class woman. It was a final fictional reworking of a theme which he had always written about for the chance it gave him to concentrate on sexual attraction (and to some extent had enacted in his own life and relationships), but which he now returned to both polemically and nostalgically."

The highly explicit sex passages in the book meant that Lawrence was unable to find a publisher for the novel. With the help of the Italian bookseller Pino Orioli, Lawrence arranged for Lady Chatterley's Lover to be printed in and distributed from Florence. The book made him so much money that he could now afford to live in expensive hotels. Later he moved to Bandol on the south coast of France.

On this day in 1965 Norman Morrison, a 31-year-old Quaker, sets himself on fire below Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara's Pentagon office, to protest the use of napalm in the Vietnam War. That morning Morrison left home with his baby daughter Emily, drove 40 miles to Washington DC, and just yards from the Pentagon, poured kerosene over himself before striking a match.

Coming home after collecting their two older children from school, his wife, Anne, had no idea what Norman had done. But as night fell, she wondered where he had taken Emily. Then the phone rang. It was a journalist. Realising she had no idea what had happened, he suggested she phone the hospital.

The day after his death, a letter arrived addressed to Anne in Norman's handwriting. "Dearest Anne," it began, "please don't condemn me. For weeks, even months, I have been praying only that I be shown what I must do. This morning with no warning I was shown."

Morrison was following the example of the Buddhist monk, Thich Quang Due, and publically burnt himself to death. In the weeks that were to follow, two other pacifists, Roger La Porte and Alice Herz, also immolated themselves in protest against the war.