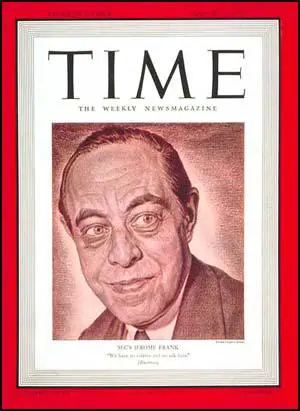

Jerome Frank

Jerome Frank was born in New York City on 10th September, 1889. He received a degree from the University of Chicago in 1909 and obtained his law degree from the University of Chicago Law School in 1912. After leaving university he worked as a lawyer in private practice in Chicago.

In March, 1933, President Franklin D. Roosevelt appointed Henry A. Wallace as Secretary of State for Agriculture in March, 1933. Felix Frankfurter suggested that Frank would be a useful addition to the department. According to William E. Leuchtenburg, the author of The FDR Years (1995), Frank had confided to Frankfurter: "I know you know Roosevelt very well. I want to get out of this Wall Street racket... This crisis seems to be the equivalent of a war and I'd like to join up for the duration." As a result, Wallace appointed Frank as general council to the Agricultural Adjustment Act (AAA).

Frank worked under George N. Peek, who was the head of the AAA. John C. Culver and John C. Hyde, the authors of American Dreamer: A Life of Henry A. Wallace (2001) have argued that Peek never liked Frank and wanted to appoint his own general council: "Crusty and dogmatic, Peek still seethed with resentment over Wallace's appointment as secretary, a position he coveted... Frank was liberal, brash, and Jewish. Peek loathed everything about him. In addition, Frank surrounded himself with idealistic left-wing lawyers... whom Peek also despised." This group of left-wing idealists included Frederic C. Howe, Adlai Stevenson, Alger Hiss, Lee Pressman, Hope Hale Davis and Gardner Jackson. Peek later wrote that the "place was crawling with... fanatic-like... socialists and internationalists."

Peek's main objective was to raise agricultural prices through cooperation with processors and large agribusinesses. Other members of the Agricultural Department such as Jerome Frank were primarily concerned to promote social justice for small farmers and consumers. On 15th November, 1933, Peek demanded that Henry A. Wallace should fire Frank for insubordination. Wallace, who agreed more with Frank than Peek, refused.

John Kennedy Ohl, the author of Hugh S. Johnson and the New Deal (1985) has argued: "In order to raise prices paid to farmers, Peek was willing to give the food processors almost any type of controls they wanted; Frank and Tugwell, however, were appalled by these agreements. In their opinion the processors owed something to the government in exchange for immunity from the antitrust laws. They also believed that there should be a check on excessive prices and unreasonable profits, ideally in the form of clauses providing for quality standards and full access by the government to company books and records. Whenever possible, Frank held up approval of Peek's marketing agreements with questions about their legality, while others from Agriculture protested them in the name of the consumer."

In December 1933, Wallace accompanied President Franklin D. Roosevelt on a visit to Warm Springs. George N. Peek seized the opportunity to announce a half-million-dollar plan to subsidize the sale of butter in Europe. Peek's action was intended as a declaration of independence, but Rexford Tugwell, acting secretary in Wallace's absence, took it as insubordination. Tugwell wrote in his autobiography that "it was becoming obvious that if we did not get rid of George Peek, he would get rid of us." He said this to Roosevelt and it was agreed that Peek should be moved from the AAA.

A few days later, Wallace made a speech where he said the dairy program had been a failure. Although he did not make reference to George N. Peek, it was clearly a comment of his policy at the AAA. John Franklin Carter commented: "That is the coolest political murder that has been committed since Roosevelt came into office." Peek resigned from the AAA on 11th December, 1933. Peek was replaced by Chester R. Davis.

In June 1934 the Southern Tenant Farmers' Union (STFU) was established in response to allegations that an absentee landlord had evicted some forty tenant families in Arkansas. Led by socialists, the STFU promoted the idea that blacks and whites could work efficiently together. According to William E. Leuchtenburg, the author of Franklin D. Roosevelt and the New Deal (1963): "It was in Arkansas that croppers and farm laborers, driven to rebellion by the hard handed tactics of the landlords and the AAA committees, established the Southern Tenant Farmers' Union in July, 1934. Under socialist leadership, the farmers, Negro and white-some of the whites had been Klansmen-organized in the region around Tyronza."

The landlords struck back with a campaign of terrorism." The journalist, Dorothy Detzer, argued: "Riding bosses hunted down union organizers like runaway slaves; union members were flogged, jailed, shot-some were murdered." Norman Thomas told a nationwide radio audience: "It will end either in the establishment of complete slavish submission to the vilest exploitation in America or in bloodshed, or in both."

Frank, Lee Pressman and Alger Hiss, decided to draw up legislation that would protect sharecroppers from their landlords. They were aware that Chester R. Davis, the head of the Agricultural Adjustment Act (AAA), did not support this move. They therefore persuaded Victor Christgau, his second in command to send out details of the change in the name of Henry A. Wallace. Davis was furious when he discovered what had happened. He later recalled: "The new interpretations completely reversed the basis on which cotton contracts had been administered through the first year. If the contract had been so construed, and if the Department of Agriculture had enforced it, Henry Wallace would have been forced out of the Cabinet within a month. The effects would have been revolutionary."

In February 1935, Davis insisted that Frank and Hiss should be dismissed. Wallace was unable to protect them: "I had no doubt that Frank and Hiss were animated by the highest motives, but their lack of agricultural background exposed them to the danger of going to absurd lengths... I was convinced that from a legal point of view they had nothing to stand on and that they allowed their social preconceptions to lead them to something which was not only indefensible from a practical, agricultural point of view, but also bad law."

Chester R. Davis told Frank: "I've had a chance to watch you and I think you are an outright revolutionary, whether you realize it or not". Wallace wrote in his diary: "I indicated that I believed Frank and Hiss had been loyal to me at all times, but it was necessary to clear up an administrative situation and that I agreed with Davis". According to Sidney Baldwin, the author of Poverty and Politics: The Rise and Decline of the Farm Security Administration (1968), Wallace greeted Frank with tears in his eyes: "Jerome, you've been the best fighter I've had for my ideas, but I've had to fire you... The farm people are just too strong."

Rexford Tugwell was unhappy with Wallace's decision and thought he should have sacked Chester R. Davis instead: "He (Wallace) gave up his policy. It was more a failure of leadership than anything else. It was letting himself be pushed around by what I thought were pretty sinister forces." Raymond Gram Swing, wrote in the Nation Magazine that Wallace had shown himself unwilling to stand up to big producers and agribusiness and seize "economic power from the interests in agriculture who hold it."

President Franklin D. Roosevelt appreciated the ability of Frank and in 1935 he appointed him as a special counsel to the Reconstruction Finance Association. In 1937, Roosevelt named Frank as a commissioner of the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC). He became Chairman of the SEC in 1939. In February 1941, Roosevelt named Frank as a judge of the United States Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit.

Jerome Frank died of a heart attack in New Haven, Connecticut, on 13th January, 1957.

Primary Sources

(1) John Kennedy Ohl, Hugh S. Johnson and the New Deal (1985)

In August 1933, Peek attempted to outflank Johnson by having Roosevelt exempt from the President's Reemployment Agreement "any industry which has to do with agriculture or any of its products." Johnson, however, effectively stymied Peek. He convinced Roosevelt that Peek's proposal was simply "a move on the part of the food chains and others who thought they would have a better chance under Agriculture." He also reminded the president that exemption of any agriculture-related industry from the blanket code would practically exempt most major industries in the nation and bring an end to the code. Even if it were possible to minimize the exemptions, Johnson added, it would not be efficacious to approve Peek's request. NRA worked at top speed, while AAA worked more deliberately; and from a psychological perspective, the first should not be geared to the latter.

During the late summer and fall of 1933, members of the Department of Agriculture attacked Johnson almost daily. Jerome Frank recalled: "All of us took a hand at it - Peek for his reason, Wallace and Tugwell and the economists for other reasons." The feud carried over to Washington social circles, always somewhat incestuous with government. One August night at a party given by columnist Drew Pearson, Johnson had "a hell of a hot discussion," which lasted for hours and took the form of a "powwow against Hugh Johnson," with Frank, Tugwell, and others from Agriculture. Though Johnson had only Robbie to back him up, he more than held his own."

On October 12, 1933, Johnson had "a fine visit" with Peek and Wallace, prompting Wallace to write to newsman Paul Anderson that "things in the official family are beginning to straighten out." Wallace, however, was too optimistic. As the NRA codes began to take effect, industrial prices climbed, forcing farmers to pay more for the products they bought. Frank, Tugwell, Mordecai Ezekiel, and others in the Department of Agriculture responded by stepping up their attacks on Johnson and NRA. Johnson retaliated by branding the farm "intellectuals" as "professors who wear the heaviest of horn-rimmed glasses." The professors hurled back such epigrams as "Johnson is a sheep in wolf's clothing."

During the last months of 1933, Johnson's feud with the Department of Agriculture centered on the marketing agreements Peek was arranging to control the quantity of commodities released for sale. In order to raise prices paid to farmers, Peek was willing to give the food processors almost any type of controls they wanted; Frank and Tugwell, however, were appalled by these agreements. In their opinion the processors owed something to the government in exchange for immunity from the antitrust laws. They also believed that there should be a check on excessive prices and unreasonable profits, ideally in the form of clauses providing for quality standards and full access by the government to company books and records. Whenever possible, Frank held up approval of Peek's marketing agreements with questions about their legality, while others from Agriculture protested them in the name of the consumer.