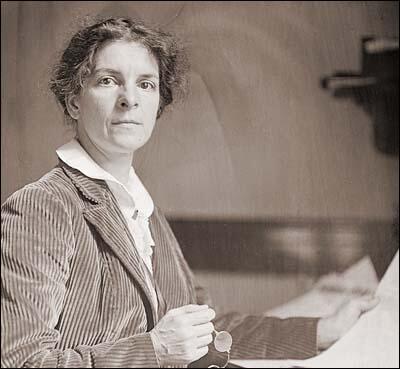

Rheta Childe Dorr

Rita Childe Dorr was born in Omaha on 2nd November 1866. After graduating from the University of Nebraska she moved to New York City in 1890 and eventually found work with the New York Evening Post.

A supporter of women's suffrage, Dorr wrote a great deal about the reform movement. This included the campaign to end child labour and an improvement in trade union rights. She was also a regular contributor to Hampton's Magazine and soon established her as a leading muckraker journalist. In 1910 a collection of her articles, What Eight Million Women Want, was published. The book was very successful and sold over half a million copies.

In 1912 Dorr travelled to Europe where she interviewed leading figures in the suffrage movement. She met Emmeline Pankhurst and became a strong supporter of the kind of direct action favoured by the Women Social & Political Union.

On her return to the United States Dorr joined the Congressional Union for Woman Suffrage and became the first editor of its journal, The Suffragist. Like the leaders of the Women Social & Political Union, Dorr supported participation in the First World War. This alienated from her former reform friends, many of whom worked for the Woman's Peace Party.

Rita Childe Dorr died on 8th August 1948.

Primary Sources

(1) Rheta Childe Dorr, What Eight Million Women Want (1910)

Not only in the United States, but in every constitutional country in the world the movement towards admitting women to full political equality with men is gathering strength. In half a dozen countries women are already completely enfranchised. In England the opposition is seeking terms of surrender. In the United States the stoutest enemy of the movement acknowledges that woman suffrage is ultimately inevitable. The voting strength of the world is about to be doubled, and the new element is absolutely an unknown quantity. Does anyone question that this is the most important political fact the modern world has ever faced?

I have asked you to consider three facts, but in reality they are but three manifestations of one fact, to my mind the most important human fact society has yet encountered. Women have ceased to exist as a subsidiary class in the community. They are no longer wholly dependent, economically, intellectually, and spiritually, on a ruling class of men. They look on life with the eyes of reasoning adults, where once they regarded it as trusting children. Women now form a new social group, separate, and to a degree homogeneous. Already they have evolved a group opinion and a group ideal.

And this brings me to my reason for believing that society will soon be compelled to make a serious survey of the opinions and ideals of women. As far as these have found collective expressions, it is evident that they differ very radically from accepted opinions and ideals of men. As a matter of fact, it is inevitable that this should be so. Back of the differences between the masculine and the feminine ideal lie centuries of different habits, different duties, different ambitions, different opportunities, different rewards.

Women, since society became an organized body, have been engaged in the rearing, as well as the bearing of children. They have made the home, they have cared for the sick, ministered to the aged, and given to the poor. The universal destiny of the mass of women trained them to feed and clothe, to invent, manufacture, build, repair, contrive, conserve, economize. They lived lives of constant service, within the narrow confines of a home. Their labor was given to those they loved, and the reward they looked for was purely a spiritual reward.

A thousand generations of service, unpaid, loving, intimate, must have left the strongest kind of a mental habit in its wake. Women, when they emerged from the seclusion of their homes and began to mingle in the world procession, when they were thrown on their own financial responsibility, found themselves willy-nilly in the ranks of the producers, the wage earners; when the enlightenment of education was no longer denied them, when their responsibilities ceased to be entirely domestic and became somewhat social, when, in a word, women began to think, they naturally thought in human terms. They couldn't have thought otherwise if they had tried.

They might have learned, it is true. In certain circumstances women might have been persuaded to adopt the commercial habit of thought. But the circumstances were exactly propitious for the encouragement of the old-time woman habit of service. The modern thinking, planning, self-governing, educated woman came into a world which is losing faith in the commercial ideal, and is endeavoring to substitute in its place a social ideal. She came into a generation which is reaching passionate hands towards democracy. She became one with a nation which is weary of wars and hatreds, impatient with greed and privilege, sickened of poverty, disease, and social injustice. The modern, free-functioning woman accepted without the slightest difficulty these new ideals of democracy and social service. Where men could do little more than theorize in these matters, women were able easily and effectively to act.

I hope that I shall not be suspected of ascribing to women any ingrained or fundamental moral superiority to men. Women are not better than men. The mantle of moral superiority forced upon them as a substitute for intellectual equality they accepted, because they could not help themselves. They dropped it as soon as the substitute was no longer necessary.

(2) Rheta Childe Dorr, Good Housekeeping (September 1925)

The whole question of restrictive legislation applied to adult women workers is obscured by a fogginess of thought, a confusion of ideas and arguments, based on propaganda rather than on facts. Back of the whole question lie ages of prejudice against any freedom for women, any acknowledgment of their right to function as independent, self-determining citizens. To deal with it properly requires cool thinking, clear intelligence. But if I did not believe that the readers of Good Housekeeping were willing to bring intelligence to bear on the subject, I should not be writing this protest against the whole body of laws, those in force and those projected, which on a sex basis alone limit the right of grown women to compete in the industrial world on equal terms with men. My first protest is against classing grown women with children under the law. Practically all laws limiting hours of work, prohibiting night work, and providing for a minimum wage are enacted for women and minors. I say "practically" just to be on the safe side. As a matter of fact, it is the routine thing to class woman labor with child labor or adolescent boy and girl labor.

The reason given is that the vast majority of "females in gainful occupations" are girls of tender years, temporary invaders of industry, pathetic flitters between the schoolroom and the matrimonial altar. I could, if I had space, quote statistical tables to prove the untruth of these generalizations. Few would read the statistics, and besides I would rather have Good Housekeeping readers think of working women as human beings rather than rows of figures. However, I will state that the last census gave the number of women, eighteen and over, in industry as 7,503,709. Nearly two million of these adult women were married. These wage-earners are not children. Why interfere with their right to earn the highest possible wage by putting them under the police power of the State? All the arguments in favor of such a policy boil down to one sentimental aphorism, "Women are women." Different from men. Weaker. More susceptible to accidents and to industrial diseases. Helpless under exploiting employers, defenseless after dark. Above all, they are mothers or potential mothers. Everybody, especially the women themselves, might be thinking about that all the time instead of such material advantages as richer lives, promotion into skilled trades, increased incomes, savings against old age. All so-called protective legislation is based on this "women are women" argument. It was the basis and foundation of the celebrated Brandeis brief supplied by the Consumers' League in defense of the Nine Hour Law in Oregon. On that brief Justice Brewer of the United States Supreme Court wrote his decision upon which took away from American working women rights guaranteed all other citizens under the Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution, the right to "Life, liberty, and property," of which the right "freely to contract" is an essential part.