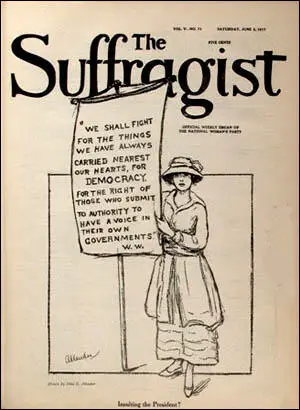

The Suffragist

In 1913 Alice Paul and the Congressional Union for Women Suffrage (CUWS) started its own magazine, The Suffragist. Its first editor was the veteran muckraking journalist, Rheta Childe Dorr. The magazine published articles by leading members such as Alice Paul, Lucy Burns and Inez Milholland. Its main cartoonist was the outstanding artist, Nina Allender. It journal also published cartoons by Cornelia Barns, Rollin Kirby and Boardman Robinson. (1)

Nina Allender emerged as being the most important cartoonist at the newspaper. Yolanda Reynoso Aguilar has argued: "Nina Allender viewed herself as more of a painter, there was hesitation towards the beginning of her endeavors of being a cartoonist. Though that uncertainty became quickly forgotten as her cartoons were showcased weekly on the cover of the Suffragist newspaper. Her cartoons became a trademark... Her earlier works played off traditional gender roles and she soon began to create works that featured that were then labeled as the Allender girl." (2)

It was said: "She (Nina Allender) gave to the American public in cartoons that have been widely copied and commented on, a new type of suffragist - the young and zealous women of a new generation determined to wait no longer for a just right. It was Mrs. Allender's cartoons more than any other one thing that in the newspapers of this country began to change the cartoonist's idea of the suffragist." (3)

Laura Myers has pointed out: "Male cartoonists often drew suffragists as unattractive old maids with thick spectacles and wielding battle axes, or portrayed them as too hysterical to vote." Allender answered this with portraits of "smart modern women" seeking the vote to gain an equal voice in a male-run government. She quotes Alice Sheppard as saying "you cannot argue against a picture." (4)

It has been claimed that this was a strategy developed by Alice Paul: "When Alice Paul recruited a cartoonist for her newspaper The Suffragist in 1914, the idea of that activist was already sketched in the public mind and it was not pretty. Throughout the 19th century and into the 20th, Americans had encountered countless images showing women suffragists as old, mannish and unattractive. In pursuing the vote, women were portrayed as threatening national values, the sanctity of the home and their husbands' masculinity.... Suffragist artists fought back on a black-and-white battlefield, developing imagery to subvert negative portrayals. In the 1910s, these cartoons were key to America's reimagining who a suffragist was and to winning sympathy for the cause." (5)

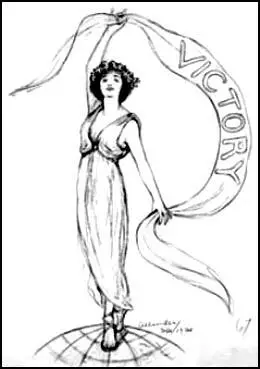

Allender was not the only cartoonist creating a new image of women fighting for the vote: Lou Rogers and Blanche Ames were also involved in this campaign "The three of them began to turn things around with their political cartoons that were witty, sharp, and attacking the power that was trying to silence them. This new and modern-day women that was being depicted as the Allender girl, showed a spirit of daring and pride as well as possessing youth. " (6)

Primary Sources

(1) The Suffragist (23rd February, 1918)

She (Nina Allender) gave to the American public in cartoons that have been widely copied and commented on, a new type of suffragist - the young and zealous women of a new generation determined to wait no longer for a just right. It was Mrs. Allender's cartoons more than any other one thing that in the newspapers of this country began to change the cartoonist's idea of the suffragist.

(2) Anna Diamond, New York Times (14 August 2020)

When Alice Paul recruited a cartoonist for her newspaper The Suffragist in 1914, the idea of that activist was already sketched in the public mind and it was not pretty. Throughout the 19th century and into the 20th, Americans had encountered countless images showing women suffragists as old, mannish and unattractive. In pursuing the vote, women were portrayed as threatening national values, the sanctity of the home and their husbands' masculinity.

It was impossible to miss such representations. Whether in newspapers, on posters or on buildings around town, "all Americans encountered cartoons," according to Allison K. Lange, author of Picturing Political Power: Images in the Women's Suffrage Movement.

Suffragist artists fought back on a black-and-white battlefield, developing imagery to subvert negative portrayals. In the 1910s, these cartoons were key to America's reimagining who a suffragist was and to winning sympathy for the cause.

Paul enlisted Nina Allender, an artist and women's rights activist, to shape the image of a charming and energetic suffragist for the Congressional Union for Woman Suffrage (a precursor to the National Woman's Party, or N.W.P.). It was important that the Allender Girl be created in a style that was widely recognizable, according to the historian Rebecca McCarron.

Following in the illustrated tradition of the independent "New Woman" and the era's iconic Gibson and Brinkley Girls, she was a stylish ideal of educated, youthful femininity and middle-class respectability. That was essential to offsetting the N.W.P.'s more militant strategies, like picketing the White House and holding hunger strikes in jail.

Other images, like those distributed by the National American Woman Suffrage Association, rebutted claims that women's voting rights endangered the home. Rose O'Neill, creator of the popular cherubic Kewpie babies, sent her characters marching under banners demanding "Votes for Our Mothers." Cartoons by artists like O'Neill, Blanche Ames Ames and Mary Ellen Sigsbee argued that women needed the vote precisely because they were caring and virtuous mothers, Lange said.

Annie Lucasta Rogers, who adopted the androgynous name Lou Rogers to advance her career, was a member of the radical feminist club Heterodoxy. (Her depiction of a woman tearing off the bonds of disenfranchisement strongly influenced the imagery of Wonder Woman, according to Jill Lepore's book "The Secret History of Wonder Woman.") She explained in a 1913 interview that her cartoons were "a chance to help women see their own problems, help bring out the things that are true in the traditions that have bound them; help show up the things that are false."

Whether the images featured girlish, maternal or symbolic figures, the protagonists, and the artists who drew them, were white. Though there were many women of color who were passionate suffragists, their absence in the cartoons spoke to a larger strategy adopted by many reformers to appease white supremacist politicians and suffragists and obscure the contributions of women who were not white.

The National Association of Colored Women produced portraits of leaders like Mary Church Terrell, but, Lange said, they lacked the same resources and infrastructure to widely shape their public image. One rare example - perhaps the only one - of a cartoon in support of Black women's suffrage was printed in the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People's publication The Crisis with the title "Woman to the Rescue!" It shows a Black mother protecting her children against birds of prey representing Jim Crow and segregation.

Soon after the Allender Girl celebrated her hard-won victory in The Suffragist, her creator moved on to Paul's next pursuit - the passage of the Equal Rights Amendment, in the pages of the N.W.P.'s new magazine, Equal Rights. But 100 years later, American women are still at that drawing board.