On this day on 25th March

On this day in 1807 the Abolition of the Slave Trade Act becomes law. In 1805 the House of Commons passed a bill that made it unlawful for any British subject to capture and transport slaves, but the measure was blocked by the House of Lords.

In February 1806, Lord Grenville formed a Whig administration. Grenville and his Foreign Secretary, Charles Fox, were strong opponents of the slave trade. Fox and William Wilberforce led the campaign in the House of Commons, whereas Grenville, had the task of persuading the House of Lords to accept the measure.

Greenville made a passionate speech where he argued that the trade was "contrary to the principles of justice, humanity and sound policy" and criticised fellow members for "not having abolished the trade long ago". When the vote was taken the Abolition of the Slave Trade bill was passed in the House of Lords by 41 votes to 20. In the House of Commons it was carried by 114 to 15 and it become law on 25th March, 1807.

British captains who were caught continuing the trade were fined £100 for every slave found on board. However, this law did not stop the British slave trade. If slave-ships were in danger of being captured by the British navy, captains often reduced the fines they had to pay by ordering the slaves to be thrown into the sea.

Some people involved in the anti-slave trade campaign such as Thomas Clarkson and Thomas Fowell Buxton, argued that the only way to end the suffering of the slaves was to make slavery illegal. However, it was not until 1833 that Parliament passed the Slavery Abolition Act.

On this day in 1811 Percy Bysshe Shelley is expelled from the University of Oxford for publishing the pamphlet, The Necessity of Atheism. Shelley, the son of Sir Timothy Shelley, the M.P. for New Shoreham, was born at Field Place near Horsham, in 1792. Sir Timothy Shelley sat for a seat under the control of the Duke of Norfolk and supported his patron's policies of electoral reform and Catholic Emancipation.

Shelley was educated at Eton and Oxford University and it was assumed that when he was twenty-one he would inherit his father's seat in Parliament. As a young man he was taken to the House of Commons where he met Sir Francis Burdett, the Radical M.P. for Westminster. Shelley, who had developed a strong hatred of tyranny while at Eton, was impressed by Burdett, and in 1810 dedicated one of his first poems to him. At university Shelley began reading books by radical political writers such as Tom Paine and William Godwin.

At university Shelley wrote articles defending Daniel Isaac Eaton, a bookseller charged with selling books by Tom Paine and the much persecuted Radical publisher, Richard Carlile. This resulted in him writing he Necessity of Atheism.

Shelley eloped to Scotland with Harriet Westbrook, a sixteen year old daughter of a coffee-house keeper. This created a terrible scandal and Shelley's father never forgave him for what he had done. Shelley moved to Ireland where he made revolutionary speeches on religion and politics. He also wrote a political pamphlet A Declaration of Rights, on the subject of the French Revolution, but it was considered to be too radical for distribution in Britain.

Percy Bysshe Shelley returned to England where he became involved in radical politics. He met William Godwin the husband of Mary Wollstonecraft, the author of Vindication of the Rights of Women. Shelley also renewed his friendship with Leigh Hunt, the young editor of The Examiner. Shelley helped to support Leigh Hunt financially when he was imprisoned for an article he published on the Prince Regent.

Leigh Hunt published Queen Mab, a long poem by Shelley celebrating the merits of republicanism, atheism, vegetarianism and free love. Shelley also wrote articles for The Examiner on polical subjects including an attack on the way the government had used the agent provocateur William Oliver to obtain convictions against Jeremiah Brandreth.

In 1814 Shelley fell in love and eloped with Mary, the sixteen-year-old daughter of William Godwin and Mary Wollstonecraft. For the next few years the couple travelled in Europe. Shelley continued to be involved in politics and in 1817 wrote the pamphlet A Proposal for Putting Reform to the Vote Throughout the United Kingdom. In the pamphlet Shelley suggested a national referendum on electoral reform and improvements in working class education.

Percy Bysshe Shelley was in Italy when he heard the news of the Peterloo Massacre. He immediately responded by writing The Mask of Anarchy, a poem that blamed Lord Castlereagh, Lord Sidmouth and Lord Eldon for the deaths at St. Peter's Fields. In The Call to Freedom Shelley ended his argument for non-violent mass political protest with the words: "Ye are many - they are few."

In 1822 Shelley, moved to Italy with Leigh Hunt and Lord Byron where they published the journal The Liberal. By publishing it in Italy the three men remained free from prosecution by the British authorities. The first edition of The Liberal sold 4,000 copies. Soon after its publication, Percy Bysshe Shelley was lost at sea on 8th July, 1822 while sailing to meet Leigh Hunt.

On this day in 1819 Dr Michael Ward was interviewed by Lord Kenyon's House of Lords Committee about the subject of child labour: " I have had frequent opportunities of seeing people coming out from the factories and occasionally attending as patients. Last summer I visited three cotton factories with Dr. Clough of Preston and Mr. Barker of Manchester and we could not remain ten minutes in the factory without gasping for breath. How it is possible for those who are doomed to remain there twelve or fifteen hours to endure it? If we take into account the heated temperature of the air, and the contamination of the air, it is a matter of astonishment to my mind, how the work people can bear the confinement for so great a length of time... When I was a surgeon in the infirmary, accidents were very often admitted to the infirmary, through the children's hands and arms having being caught in the machinery; in many instances the muscles, and the skin is stripped down to the bone, and in some instances a finger or two might be lost. Last summer I visited Lever Street School. The number of children at that time in the school, who were employed in factories, was 106. The number of children who had received injuries from the machinery amounted to very nearly one half. There were forty-seven injured in this way."

Edward Baines' book The History of the Cotton Manufacture (1835)

On this day in 1859 Rachel McMillan was born in New York. Her sister, Margaret McMillan, was born the following year on 20th July, 1860. Their parents, James and Jean McMillan, had originally come from Inverness but had emigrated to America in 1840. In 1865 James McMillan and his daughter Elizabeth died. Margaret also caught scarlet fever and although she survived it left her deaf (she recovered her hearing at fourteen).

Deeply upset by these events, Mrs. McMillan decided to take her two young daughters back to Scotland. Rachel and Margaret both attended the Inverness High School and were able to make good use of their grandparents well-stocked library. When Jean McMillan died in 1877 it was decided that Rachel would remain in Inverness to nurse her very sick grandmother, while Margaret was sent away to be trained as a governess.

In 1887 Rachel paid a visit to a cousin in Edinburgh. Her cousin took her to church where she heard an impressive sermon by John Glasse, a Christian Socialist. Rachel was also introduced to John Gilray, another recent convert to this religious group. Gilray gave Rachel copies of Justice, a socialist newspaper and Advice to the Young, a book by Peter Kropotkin. Rachel was impressed by what she read. She particularly liked the articles by William Morris and William Stead.

During the following week Rachel went with Gilray to several socialist meetings in Edinburgh. When she arrived home in Inverness she wrote to a friend about her new beliefs: "I think that, very soon, when these teachings and ideas are better known, people generally will declare themselves Socialists."

Rachel's grandmother died in July 1888. Freed of her nursing responsibilities, Rachel joined Margaret McMillan in London and the two remained together for most of the rest of their lives. Margaret, who was employed as a junior superintendent in a home for young girls, found Rachel a similar job in Bloomsbury.

In London Rachel and Margaret attended socialist meetings where they met William Morris, H. M. Hyndman, Peter Kropotkin, William Stead and Ben Tillet. They also began contributing to the magazine Christian Socialist and gave free evening lessons to working class girls in London. Margaret later wrote: "I taught them singing, or rather I talked to them while they jeered at me." It was at this time that the two sisters became aware of the connection between the workers' physical environment and their intellectual development.

In October 1889, Rachel and Margaret helped the workers during the London Dock Strike. The continued to be involved in spreading the word of Christian Socialism to industrial workers and in 1892 it was suggested that their efforts would be appreciated in Bradford.

Although for the next few years they were based in Bradford, Rachel and Margaret toured the industrial regions speaking at meetings and visiting the homes of the poor. As well as attending Christian Socialist meetings, the sisters joined the Fabian Society, the Labour Church, the Social Democratic Federation and the newly formed Independent Labour Party (ILP).

Margaret and Rachel's work in Bradford convinced them that they should concentrate on trying to improve the physical and intellectual welfare of the slum child. In 1892 Margaret joined Dr. James Kerr, Bradford's school medical officer, to carry out the first medical inspection of elementary school children in Britain. Kerr and McMillan published a report on the medical problems that they found and began a campaign to improve the health of children by arguing that local authorities should install bathrooms, improve ventilation and supply free school meals.

The sisters remained active in politics and Margaret McMillan became the Independent Labour Party candidate for the Bradford School Board. Elected in 1894 she was now in a position to influence what went on in Bradford schools. She also wrote several books and pamphlets on the subject including Child Labour and the Half Time System (1896) and Early Childhood (1900).

In 1902 Margaret joined her sister Rachel in London. The sisters joined the recently formed Labour Party and worked closely with leaders of the movement including James Keir Hardie and George Lansbury. Margaret continued to write books on health and education. In 1904 she published her most important book, Education Through the Imagination (1904) and followed this with The Economic Aspects of Child Labour and Education (1905).

The two sisters led the campaign for school meals and eventually the House of Commons became convinced that hungry children cannot learn and passed the 1906 Provision of School Meals Act. The legislation accepted the argument put forward by the McMillan sisters that if the state insists on compulsory education it must take responsibility for the proper nourishment of school children.

In 1908 Rachel McMillan and Margaret McMillan opened the country's first school clinic in Bow. This was followed by the Deptford Clinic in 1910 that served a number of schools in the area. The clinic provided dental help, surgical aid and lessons in breathing and posture. The sisters also established a Night Camp where slum children could wash and wear clean nightclothes.

Rachel and Margaret McMillan both supported the campaign for universal suffrage. They were against the use of violence and tended to favour the approach of the NUWSS. However, they disagreed with the way WSPU members were treated in prison and at one meeting where they were protesting against the Cat and Mouse Act, the sisters were physically assaulted by a group of policemen.

In 1914 the sisters decided to start an Open-Air Nursery School & Training Centre in Deptford. Within a few weeks there were thirty children at the school ranging in age from eighteen months to seven years. Rachel, who was mainly responsible for the kindergarten, proudly pointed out that in the first six months there was only one case of illness and, because of precautions that she took, this case of measles did not spread to the other children.

Rachel McMillan, who had suffered from poor health for a long time, died on 25th March, 1917.

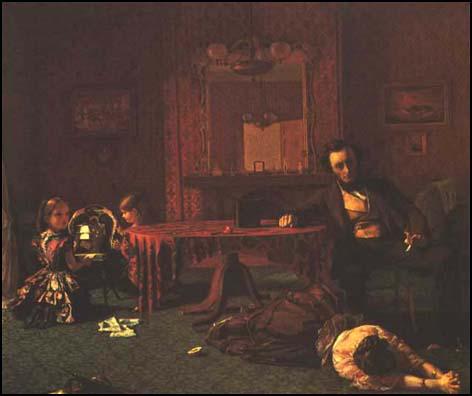

On this day in 1863 the artist Augustus Leopold Egg died. Augustus Leopold Egg was born in London on 2nd May 1816. He attended Henry Sass Drawing School in preparation for entering the Royal Academy. His painting A Spanish Girl was accepted by the Academy in 1838. At about this time he formed The Clique, a sketching club, with William Powell Frith and Richard Dadd.

In the 1840s Egg began painting comic scenes from Shakespeare, Lord Byron and Walter Scott. He also painted historical pictures such as Queen Elizabeth Discovers She is No Longer Young (1848), The Life and Death of Buckingham (1855) and The Night Before Naseby (1859).

In 1859 Egg produced a series of three paintings called Past and Present. Influenced by the moral paintings of William Hogarth, the pictures tell the story of a man that Egg knew, whose wife had been unfaithful. In the first picture the husband discovers his wife's infidelity; he holds the letter that has enabled him to discover the betrayal and crushes a picture of his wife's lover under his foot. The second and third pictures both take place at the same moment, five years later, after the death of the father. One picture shows the children alone in the home, whereas the mother is living under the Adelphi arches in London.

Egg, a friend of the writer Charles Dickens, suffered from chronic respiratory disease. In 1863 Egg was advised that his health would improve if he lived in Africa. This move was unsuccessful and Augustus Leopold Egg died in Algiers on 25th March, 1863.

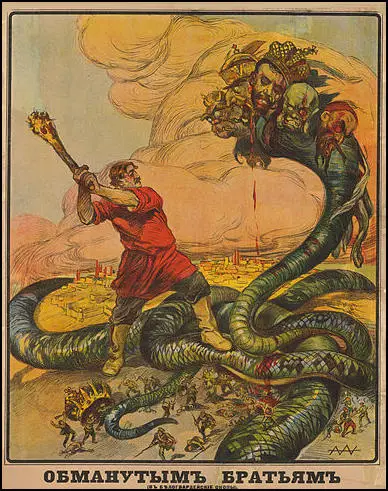

On this day in 1880 artist Alexander Apsit was born in Riga. He moved to Saint Petersburg in 1894 and attended art school and became a student of Lew Dmitriew-Kawkaski.

Aspit worked for various Russian magazines and on the outbreak of the First World War was employed by the government to design war posters. After the Bolshevik Revolution Apsit was commissioned by the State Publishing House to design revolutionary posters.

The Year of Proletarian Dictatorship was produced in October, 1918, for the first anniversary of the revolution. It shows the key elements of the revolutionary poster's imagery: a farmer with a red flag and scythe in the foreground, and a blacksmith with a hammer crushing the emblems of fallen capitalism - both as guards in front of a field of simple flags in the background an industrialized city and a rising sun.

Several posters were produced during the Russian Civil War with the intention of persuading young men to join the Red Army. The White Army was often portrayed as a monster.

After the war, he worked in Latvia as a book illustrator. In addition, he designed advertising posters and greeting cards, as well as the wrapping paper of chocolates and sweets from the company Vilhelms Ķuze. In 1939, Apsit moved to Nazi Germany, where he died in 1943. Alexander Apsit died in Ludwigslust on 19th September, 1943.

On this day in 1902 David Lloyd George attacked the proposed Education Act. He resented the idea that Nonconformists contributing to the upkeep of Anglican schools. It was also argued that school boards had introduced more progressive methods of education. He argued that "the school boards are to be destroyed because they stand for enlightenment and progress."

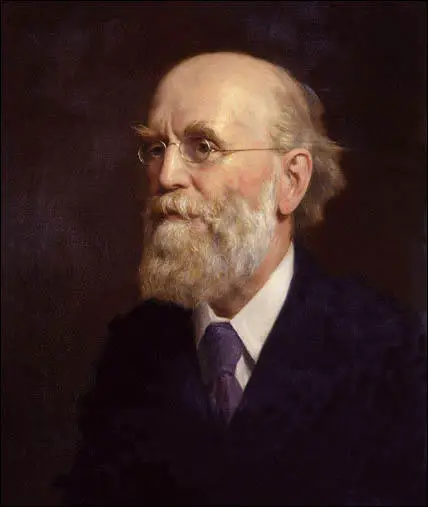

John Clifford became the leader of the campaign against the legislation. Clifford was opposed to Balfour's bill for three main reasons: (1) the rate aid was being used to support the teaching of religious views to which some rate-payers were opposed; (2) sectarian schools, supported by public funds, were not under public control; (3) teachers in sectarian schools were subject to religious tests.

Clifford prepared a plan of "Passive Resistance". It was based on the strategy used by John Hampden against Ship Money in 1637 and one of the causes of the English Civil War. "Its tactics were to be those of the old Tithe War: refuse to pay the abhorrent education rate, submit rather to the forced sale of your goods and even of your house; if need be, go to jail!".

Clifford argued that people who disagreed with the proposed Education Act should refuse to pay at least that portion of the rate which was to be spent in or on church schools. The National Passive Resistance Committee was set-up with the motto "No Say. No Pay". However, within weeks the Anti-Martyrdom League was formed to pay the rates that the passive resisters withheld. (4)

In July, 1902, a by-election at Leeds demonstrated what the education controversy was doing to party fortunes, when a Conservative Party majority of over 2,500 was turned into a Liberal majority of over 750. The following month a Baptist came near to capturing Sevenoaks from the Tories and in November, 1902, Orkney and Shetland fell to the Liberals. That month also saw a huge anti-Bill rally held in London, at Alexandra Palace.

Despite the opposition to the new Education Act, it was passed in December, 1902. John Clifford, wrote several pamphlets about the legislation that had a readership that ran into hundreds of thousands. Balfour accused him of being a victim of his own rhetoric: "Distortion and exaggeration are of its very essence. If he has to speak of our pending differences, acute no doubt, but not unprecedented, he must needs compare them to the great Civil War. If he has to describe a deputation of Nonconformist ministers presenting their case to the leader of the House of Commons, nothing less will serve him as a parallel than Luther's appearance before the Diet of Worms."

Rate refusals began in the spring of 1903. "What normally happened was that sufficient of their goods should be distrained and auctioned to defray the rate. It was usually arranged for a friend of the refuser should be on hand to buy back the goods." Over the next four years 170 men went to prison for refusing to pay their school taxes. This included 60 Primitive Methodists, 48 Baptists, 40 Congregationalists and 15 Wesleyan Methodists. John Clifford never went to prison but he appeared in court on 41 different occasions over the next ten years.

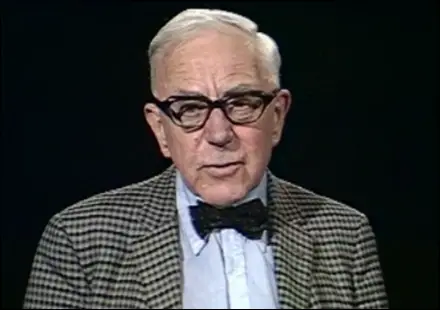

On this day in 1906 Alan John Percivale Taylor, the only son of Percy Lees Taylor, a cotton merchant, and his wife, Constance Sumner Thompson, a schoolmistress, was born at Birkdale. His parents were supporters of the Labour Party and he grew up with left-wing views.

Taylor was educated at Bootham School in York and Oriel College. A talented student he graduated from Oxford University with a first class degree in modern history in 1927. He considered the possibility of a career as a lawyer but in 1928 he decided to study diplomatic history in Vienna.

In 1930 he was appointed as a lecturer at Manchester University. Taylor also contributed regularly as reviewer and leader writer on the Manchester Guardian, where he expressed his views as a left-wing pacifist. His first book, The Italian Problem in European Diplomacy, 1847–1849, appeared in 1934.

Taylor was a strong opponent of Adolf Hitler and his government in Nazi Germany. In 1936 he resigned from the Manchester Peace Council and began to urge British rearmament. He criticised the policy of appeasement and argued for an Anglo-Soviet alliance to contain fascism. In 1938 he published Germany's First Bid for Colonies, 1884–1885 .

With the support of Lewis Namier, Taylor returned to Oxford University in 1938 as a fellow of Magdalen College. According to A.F. Thompson, one of his students: "He schooled himself to lecture (and speak publicly) without notes, a craft he later brought to perfection... Soon established as an outstanding tutor of responsive undergraduates and a charismatic, early-morning lecturer, he began to make a wider name for himself as an incisive speaker on current affairs, in person and on the radio."

During the Second World War he was a member of the Home Guard. He continued to teach history and published The Habsburg Monarchy (1941) and The Course of German History (1945). Although he was sympathetic to the plight of the Soviet Union during the Cold War, he remained a staunch critic of the rule of Joseph Stalin and in 1948 created a stir at a Stalinist cultural congress in Wrocław, when he argued that everyone had the right to hold different views from those in power.

In 1957, Taylor joined forces with J. B. Priestley, Kingsley Martin, Bertrand Russell, Fenner Brockway, Wilfred Wellock, Ernest Bader, Frank Allaun, Donald Soper, Vera Brittain, E. P. Thompson, Sydney Silverman, James Cameron, Jennie Lee, Victor Gollancz, Konni Zilliacus, Richard Acland, Stuart Hall, Ralph Miliband, Frank Cousins, Canon John Collins and Michael Foot to establish the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament.

Taylor published a large number of books on history including The Struggle for Mastery in Europe 1848-1918 (1954), The Trouble Makers: Dissent over Foreign Policy, 1792–1939 (1957), The Origins of the Second World War (1961), The First World War (1963), Politics In Wartime (1964) English History 1914-1945 (1965), From Sarajevo to Potsdam (1966), Churchill Revised: A Critical Assessment (1969) and Beaverbrook (1972). Taylor's autobiography,A Personal History, was published in 1983.

His biographer, A.F. Thompson, has argued: "Taylor emerged as a national figure with the advent of television. On In the News and Free Speech he caught the viewers' fancy as a quick-witted debater, a Cobbett-like scourge of the establishment... First of the television dons, he retained this primacy into old age as he delivered unscripted lectures direct to the camera on historical themes to a vast audience."

Alan John Percivale Taylor, who suffered from Parkinson's Disease for many years, died at a nursing home in Barnet on 7th September 1990.

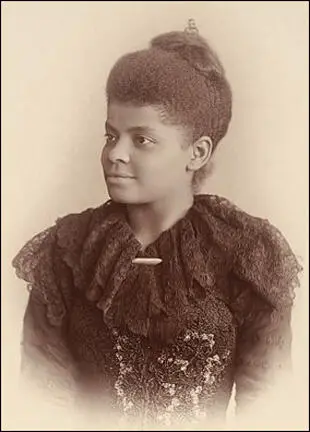

On this day in 1931 civil rights activist Ida Wells died of uremia. Ida Wells, the daughter of a carpenter, was born in Holly Springs, Mississippi, in 1862. Her parents were slaves but they family achieved freedom in 1865. When Ida was sixteen both her parents and a younger brother, died of yellow fever. At a meeting following the funeral, friends and relatives decided that the five children should be farmed out to various aunts and uncles. Ida was devastated by the idea and to keep the family together, dropped out of High School, and found employment as a teacher in a local Black school.

In 1880 Ida moved to Memphis where she attended Fisk University. Ida held strong political opinions and she upset many people with her views on women's rights. When she was 24 she wrote, "I will not begin at this late day by doing what my soul abhors; sugaring men, weak deceitful creatures, with flattery to retain them as escorts or to gratify a revenge."

Ida became a public figure in the city when in 1884 she led a campaign against segregation on the local railway. After being forcibly removed from a whites only carriage she successfully sued the Chesapeake, Ohio & South Western Railroad Company. However, this was overturned three years later by a ruling from the Tennessee Supreme Court.

In 1884 Ida began teaching in Memphis. She also wrote articles on civil rights for local newspapers and when she criticised the Memphis Board of Education for under-funding African American schools, she lost her job as a teacher.

Ida Wells used her savings to become part owner of Free Speech, a small newspaper in Memphis. Over the next few years she concentrated on writing about individual cases where black people had suffered at the hands of white racists. This included an investigation into lynching and discovered during a short period 728 black men and women had been lynched by white mobs. Of these deaths, two-thirds were for small offences such as public drunkenness and shoplifting. the first conference of the NAACP she successfully persuaded the organisation to resolve to make lynching a federal crime.

On 9th March, 1892, three African American businessmen were lynched in Memphis. When Ida wrote an article condemning the lynchers, a white mob destroyed her printing press. They declared that they intended to lynch Ida but fortunately she was visiting Philadelphia at the time. Unable to return to Memphis, Ida was recruited by the progressive newspaper, New York Age . She continued her campaign against lynching and Jim Crow laws and in 1893 and 1894 made lecture tours of Britain. While there in 1894 she helped to establish the British Anti-Lynching Committee. Members included James Keir Hardie, Thomas Burt, John Clifford, Isabella Ford, Tom Mann, Joseph Pease, C. P. Scott, Ben Tillett and Mary Humphrey Ward.

In 1894 Ida married Ferdinand Barnett, the founder of the Conservator , the first African American newspaper in Chicago. Ida gave birth to four children: Charles (1896), Herman (1897), Ida (1901) and Alfreda (1904). She continued her involvement in politics and wrote pamphlets such as Southern Horrors: Lynch Law in All Its Phases.

In 1901 Ida published her book, Lynching and the Excuse for It. In the book she argued that the main aim of lynching was to intimidate blacks from becoming involved in politics and therefore maintaining white power in the South.

Ida was also one of the founders of the National Association for the Advancement of Coloured People (NAACP) in 1909. At the first conference of the NAACP she successfully persuaded the organisation to resolve to make lynching a federal crime.

An early supporter of women's suffrage, Ida created a stir in 1913 when she refused to march at the back with other black delegates during a demonstration organised by the National American Women Suffrage.

Ida, who wrote for the Chicago Tribune, campaigned for racial equality in the United States Army during the First World War. This included publicizing the execution of black soldiers for minor offences while fighting for their country. After her retirement, Ida wrote her autobiography, Crusade for Justice (1928).

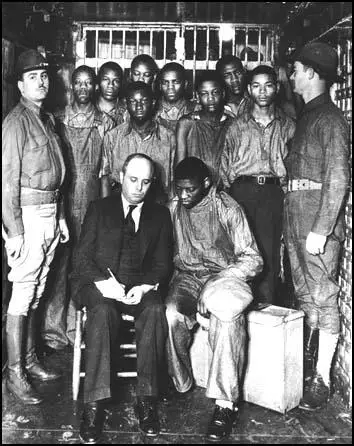

On this day in 1931 the Scottsboro Boys are arrested in Alabama and charged with rape. Victoria Price (21) and Ruby Bates (17) claimed they were gang-raped by 12 black men on a Memphis bound train. Nine black youths on the train were arrested and charged with the crime. Twelve days later the trial of Haywood Patterson, Charles Weems, Clarence Norris, Andy Wright, Ozzie Powell, Olen Montgomery, Eugene Williams and Willie Roberson took place at Scottsboro, Alabama. Their defence attorney was an alcoholic, who was drunk throughout the trial. The prosecutor on the other hand, told the jury, "Guilty or not, let's get rid of these niggers". After three days all nine men were found guilty: eight, including two aged 14, were sentenced to death and the youngest man, who was only thirteen, was given life imprisonment.

John Gates later wrote: "A few weeks after I joined the YCL (Young Communist League), nine young Negroes were arrested on a freight train near Scottsboro, Alabama, convicted of raping two white women and sentenced to the electric chair. This was the famous Scottsboro case. It was to have lasting significance for our country and to set off a chain reaction that is still felt throughout the world.... The plight of an entire people was suddenly illumined for me. Besides, some of the Scottsboro Boys themselves were of my own age; they were victims of the same depression which affected all of us in one way or another. The role of the Communists in the case confirmed my conviction that I had been right in joining up with them."

Two famous writers, Theodore Dreiser and Lincoln Steffens, publicized the case by writing articles on how the men had been falsely convicted. The National Association for the Advancement of Coloured People (NAACP) and the American Communist Party both became involved in the campaign and Clarence Darrow, America's leading criminal lawyer, took up the case. In November, 1932, the United States Supreme Court ordered a second trial on the grounds that the men had been inadequately defended in court.

Although Ruby Bates testified at the second trial that the rape story had been invented by Victoria Price and the crime had not taken place, the men were once again found guilty. Mary Heaton Vorse wrote: "The Scottsboro case is not simply one of race hatred. It arose from the life that was followed by both accusers and accused, girls and boys, white and black. If it was intolerance and race prejudice which convicted Haywood Patterson, it was poverty and ignorance which wrongfully accused him."

Heywood Broun, probably the most popular journalist in the United States at the time, took up the case. He also wrote about the conviction of the innocent Tom Mooney. However, in 1933 he was expelled from the Socialist Party of America after appearing with members of the Communist Party at a rally demanding the release of these men. Broun wrote in the New York World-Telegram on 29th April 1933: "I don't expect the Communists to love me, and I'm not going to love them. I hope from time to time to say many things about them, and I expect the same in return. But I think it would be a fine idea not to fight until Tom Mooney is free and the Scottsboro boys are acquitted."

A third trial ended with the same result but a fourth in January, 1936, resulted in four of the men being acquitted. Lincoln Steffens, like many other journalists, continued with his campaign. "No state in this union has a right to speak of justice as long as the most friendless Negro child accused of a crime receives less than the best defence that would be given its wealthiest white citizen."

Richard B. Moore, was another civil rights activist who campaigned for the men's release. In 1940 he argued: "The Scottsboro Case is one of the historic landmarks in the struggle of the American people and of the progressive forces throughout the world for justice, civil rights and democracy. In the present period, the Scottsboro Case has represented a pivotal point around which labor and progressive forces have rallied not only to save the lives of nine boys who were framed... but also against the whole system of lynching terror and the special oppression and persecution of the Negro people... Last year we came to a new development in the Scottsboro Case which shows more clearly than ever before the fascist nature of this case. Governor Graves (of Alabama) gave his pledged word to the Scottsboro Defense Committee and to leading Alabama citizens at a hearing to release the remaining Scottsboro boys." Four more of the men were released in the 1940s but the last prisoner, Andy Wright, had to wait until 9th June, 1950, before achieving his freedom. This was nineteen years and two months after his arrest in Alabama.

The nine men were finally pardoned in October, 1976. Only one of the men, Clarence Norris, who had spent 15 years in prison for the crime, was still alive. He commented when he heard the news: "I only wish the other eight boys could be here today. Their lives were ruined by this thing, too." In April 1977 the Alabama House Judiciary Committee rejected a proposal to pay Norris $10,000 in compensation for his time spent in prison. The last of the group, Clarence Norris, died in 1989.

On 20th November, 2013, Alabama’s parole board granted posthumous pardons for the three remaining members of the group who had yet to have their convictions rescinded, Haywood Patterson, Charles Weems and Andy Wright. Sheila Washington, a Scottsboro resident who has led the campaign to pardon the men, told The Guardian that holding the three pardon certificates in her hand had been “joyous and sad at the same time. I feel like jumping up and down and rejoicing for them, because this is something they wanted in their lifetimes but it never happened.”

On this day in 1933 the Manchester Guardian publishes article on the famine in the Soviet Union. The journalist, Malcolm Muggeridge knew that his reports would be censored and so he sent them out of the country in the British diplomatic bag. Muggeridge wrote: "I mean starving in its absolute sense; not undernourished as, for example, most Oriental peasants... and some unemployed workers in Europe, but having had for weeks next to nothing to eat." Muggeridge quoted one peasant as saying: "We have nothing. They have taken everything away." Muggeridge supported this view: "It was true. The famine is an organized one." He went to Kuban where he saw well-fed troops being used to coerce peasant starving to death. Muggeridge argued it was "a military occupation; worse, active war" against the peasants.

Muggeridge travelled to Rostov-on-Don and found further examples of mass starvation. He claimed that many of the peasants had bodies swollen from hunger, and there was an "all-pervading sight and smell of death." When he asked why they did not have enough to eat, the inevitable answer came that the food had been taken by the government. Muggeridge reported on 28th March: "To say that there is a famine in some of the most fertile parts of Russia is to say much less than the truth; there is not only famine but - in the case of the North Caucasus at least - a state of war, a military occupation."

On 31st March, 1933, The Evening Standard carried a report by Gareth Jones: "The main result of the Five Year Plan has been the tragic ruin of Russian agriculture. This ruin I saw in its grim reality. I tramped through a number of villages in the snow of March. I saw children with swollen bellies. I slept in peasants’ huts, sometimes nine of us in one room. I talked to every peasant I met, and the general conclusion I draw is that the present state of Russian agriculture is already catastrophic but that in a year’s time its condition will have worsened tenfold... The Five-Year Plan has built many fine factories. But it is bread that makes factory wheels go round, and the Five-Year Plan has destroyed the bread-supplier of Russia."

William Henry Chamberlin told officials at the British Embassy that he estimated that two million had died in Kazakhstan, a half a million in the North Caucasus, and two million in the Ukraine. Historians have estimated that as many as seven million people died during this period. Journalists based in Moscow were willing to accept the word of the Soviet authorities for their information. Walter Duranty even told his friend, Hubert Knickerbocker, that the reported famine "is mostly bunk".

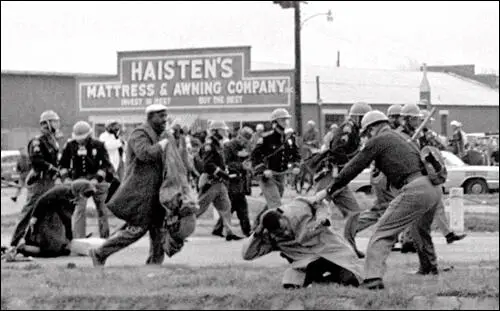

On this day in 1965 Martin Luther King led 25,000 people to the Alabama State Capitol.and handed a petition to Governor George Wallace, demanding voting rights for African Americans. That night, the Ku Klux Klan killed Viola Liuzzo while returning from the march.

On 6th August, 1965, Lyndon B. Johnson signed the Voting Rights Act. This removed the right of states to impose restrictions on who could vote in elections. Johnson explained how: "Every American citizen must have an equal right to vote. Yet the harsh fact is that in many places in this country men and women are kept from voting simply because they are Negroes." The legislation now empowered the national government to register those whom the states refused to put on the voting list.

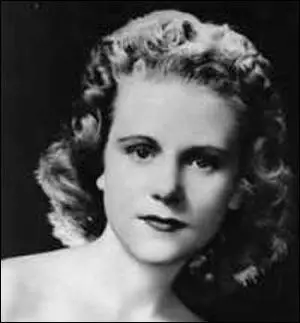

On this day in 1965 civil rights campaigner Viola Liuzzo is murdered by the Ku Klux Klan. Viola Fauver was born in Pennsylvania on 11th April, 1925. As a child, Viola lived in Tennessee and Georgia. After an unsuccessful marriage and the birth of two children, Viola married Anthony J. Liuzzo, a Teamster Union official from Detroit. Viola had three more children and at the age of 36 she resumed her education at Wayne State University. After graduating with top honors Viola became a medical lab technician.

A member of the NAACP, Viola decided to take part in the Selma to Montgomery march on 25th March, 1965, where Martin Luther King led 25,000 people to the Alabama State Capitol and handed a petition to Governor George Wallace, demanding voting rights for African Americans. After the demonstration had finished, Viola volunteered to help drive marchers back to Montgomery Airport. Leroy Moton, a young African American, offered to work as her co-driver.

On the way back from one of these trips to the airport, Viola and Leroy, were passed by a car carrying four members of the Ku Klux Klan from Birmingham. When they saw a white woman and black man in the car together, they immediately knew that they had both been taking part in the civil rights demonstration at Montgomery. The men decided to kill them and after driving alongside Viola's car, one of the men, Collie Wilkins, put his arm out of the window, and fired his gun. Viola Liuzzo was hit in the head twice and died instantly. Leroy was uninjured and was able to get the car under control before it crashed.

The four men in the car, Collie Wilkins (21), Gary Rowe (34), William Eaton (41) and Eugene Thomas (42) were quickly arrested. Rowe, an FBI undercover agent, testifed against the other three men. In an attempt to prejudice the case, rumours began to circulate that Viola was a member of the Communist Party and had abandoned her five children in order to have sexual relationships with African Americans involved in the civil rights movement. It was later discovered that these highly damaging stories that appeared in the press had come from the FBI.

Despite Rowe's testimony, the three members of the Ku Klux Klan were acquitted of murder by an Alabama jury. President Lyndon Johnson, instructed his officials to arrange for the men to be charged under an 1870 federal law of conspiring to deprive Viola Liuzzo of her civil rights. Wilkins, Eaton and Thomas were found guilty and sentenced to 10 years in prison.

On this day in 1969 writer Max Eastman died at his summer home in Bridgetown, Barbados, at the age of 86. Max Eastman was born in Canandaigua on 4th January, 1883. Both his parents, Samuel Eastman and Annis Ford, were church ministers. In 1889 his mother was one of the first women to be ordained as a minister. Eastman graduated from Williams College in 1905 and afterwards studied philosophy with John Dewey at Columbia University.

Barbara Gelb has argued: "The son of two Congregational ministers from upstate New York, Eastman had been raised in an atmosphere of liberal-mindedness; having a mother who was the first woman to be ordained a Congregational minister in New York State, Eastman found himself perfectly at home in sympathy with the suffragists and other social reform movements of the day."

In 1907 Eastman moved to New York City, settling in Greenwich Village with his sister Crystal Eastman. Soon afterwards Eastman met Ida Rauh. According to William L. O'Neill: "Ida Rauh, a beautiful and intelligent Jewish woman with a private income, whom Max Eastman had known since first coming to New York. She was rebelling against her bourgeois family and explained the class struggle to him so clearly that he became a socialist." Eastman was persuaded to join the Men's League for Women's Suffrage.

The couple were married on 4th May, 1911 in Patterson, New Jersey. He later recalled that he awoke the next morning seized with terror: "I had lost, in marrying Ida, my irrational joy in life." The author of The Last Romantic (1978), has argued: "Unlike his affectionate mother and sister, Ida was never one to shower people, even her husband, with compliments and attentions. Yet these were necessary to Max's well-being. She was given to periods of indolence and so could not pour vitality into Max's languid nerves as he thought essential."

Sidney Hook got to know Eastman during this period. He later recalled: "Max Eastman was authentically American, sympathetic to the great rebels of the American past, intellectually independent, drawn to an undogmatic socialism on compassionate rather than economic grounds, an ardent supporter of women's rights at a time when it was dangerous even for a woman to be known as a feminist, defender of dissemination of information about birth control, an advocate of free love and open marriage, a pioneer for civil liberties, receptive to new ideas in almost every field. Max Eastman fought in more good causes than almost any man or woman of his generation, and yet he was by no means a purely literary radical - one of those who flaunt their radical ideas but never come within hailing distance of any political activity. Eastman put his very life and career on the line in pursuit of his radical ideas. More than once he had the courage to stand up to an enraged mob."

Eastman developed a reputation as an outstanding journalist and in 1912 was invited to become editor of the left-wing magazine, The Masses. Organized like a co-operative, artists and writers who contributed to the journal shared in its management. Other radical writers and artists who joined the team included Floyd Dell, John Reed, William Walling, Crystal Eastman, Sherwood Anderson, Carl Sandburg, Upton Sinclair, Arturo Giovannitti, Michael Gold, Amy Lowell, Louise Bryant, John Sloan, Art Young, Boardman Robinson, Robert Minor, K. R. Chamberlain, Stuart Davis, Lydia Gibson, George Bellows and Maurice Becker.

In his first editorial, Eastman argued: "This magazine is owned and published cooperatively by its editors. It has no no dividends to pay, and nobody is trying to make money out of it. A revolutionary and not a reform magazine: a magazine with a sense of humour and no respect for the respectable: frank, arrogant, impertinent, searching for true causes: a magazine directed against rigidity and dogma wherever it is found: printing what is too naked or true for a money-making press: a magazine whose final policy is to do as it pleases and conciliate nobody, not even its readers."

Floyd Dell was appointed as Eastman's assistant: "Max Eastman was a tall, handsome, poetic, lazy-looking fellow... I was paid twenty-five dollars a week for helping Max Eastman get out the magazine.... At the monthly editorial meetings, where the literary editors were usually ranged on one side of all questions and the artists on the other. The squabbles between literary and art editors were usually over the question of intelligibility and propaganda versus artistic freedom; some of the artists held a smouldering grudge against the literary editors, and believed that Max Eastman and I were infringing the true freedom of art by putting jokes or titles under their pictures. John Sloan and Art Young were the only ones of the artists who were verbally quite articulate; but fat, genial Art Young sided with the literary editors usually; and John Sloan, a very vigorous and combative personality, spoke up strongly for the artists."

The Masses was often in trouble with the authorities. One of Art Young's cartoons, Poisoned at the Source, that appeared in the July 1913 edition of the magazine upset the Associated Press company and he was indicted for criminal libel. However, after a year, the company decided to drop the law suit.

Eastman, like most of the people working for The Masses, believed that the First World War had been caused by the imperialist competitive system and that the USA should remain neutral. This was reflected in the fact that the articles and cartoons that appeared in journal attacked the behaviour of both sides in the conflict.

After the USA declared war on the Central Powers in 1917, The Masses came under government pressure to change its policy. When it refused to do this, the journal lost its mailing privileges. In July, 1917, it was claimed by the authorities that cartoons by Art Young, Boardman Robinson and Henry J. Glintenkamp and articles by Eastman and Floyd Dell had violated the Espionage Act. Under this act it was an offence to publish material that undermined the war effort. One of the journals main writers, Randolph Bourne, commented: "I feel very much secluded from the world, very much out of touch with my times. The magazines I write for die violent deaths, and all my thoughts are unprintable."

Floyd Dell argued in court: "There are some laws that the individual feels he cannot obey, and he will suffer any punishment, even that of death, rather than recognize them as having authority over him. This fundamental stubbornness of the free soul, against which all the powers of the state are helpless, constitutes a conscious objection, whatever its sources may be in political or social opinion." The legal action that followed forced The Masses to cease publication. In April, 1918, after three days of deliberation, the jury failed to agree on the guilt of Dell and his fellow defendants.

The second trial was held in January 1919. John Reed, who had recently returned from Russia, was also arrested and charged with the original defendants. Floyd Dell wrote in his autobiography, Homecoming (1933): "While we waited, I began to ponder for myself the question which the jury had retired to decide. Were we innocent or guilty? We certainly hadn't conspired to do anything. But what had we tried to do? Defiantly tell the truth. For what purpose? To keep some truth alive in a world full of lies. And what was the good of that? I don't know. But I was glad I had taken part in that act of defiant truth-telling." This time eight of the twelve jurors voted for acquittal. As the First World War was now over, it was decided not to take them to court for a third time.

In 1918 Eastman joined with Art Young, Floyd Dell and his sister, Crystal Eastman, to establish another radical journal, The Liberator. Other writers and artists involved in the magazine included Claude McKay, Boardman Robinson, Robert Minor, Stuart Davis, Lydia Gibson, Maurice Becker, Helen Keller, Cornelia Barns, and William Gropper.

In 1922 the journal was taken over by Robert Minor and the Communist Party and in 1924 was renamed as The Workers' Monthly. After this Eastman left the United States and travelled to the Soviet Union. Eastman had welcomed the Russian Revolution but became disillusioned when Joseph Stalin ousted Leon Trotsky.

Eastman divorced his first wife, Ida Raub, to marry Elena Krylenko in 1924. He met her during a visit to the Soviet Union. Elena's brother, was Nikolai Krylenko, who, as president of the supreme tribunal he prosecuted all the major political trials of the 1920s. Later, Joseph Stalin appointed Krylenko as Commissar for Justice and was involved in the conviction of a large number of members of the Communist Party during the Great Purges.

Eastman went to live in France in 1924 where he wrote Since Lenin Died (1925), and Marx and Lenin: The Science of Revolution (1926). In these books Eastman warned of the dangers posed by Joseph Stalin in the Soviet Union. The book was unpopular with most American Marxists and Eastman was denounced as a rebellious individualist. Sidney Hook argued: "Of all the forms of intellectual independence Eastman displayed in his life, nothing matched the courage he had to summon up when he stood practically alone on his return from the Soviet Union in 1924. He had brought with him the first hard evidence of the Stalinization of the Bolshevik regime. In consequence, he became a rebel outcast in his own country and a pariah in the radical movement that had been central to his life."

In 1927 Eastman returned to the United States and now a supporter of Leon Trotsky, becomes his translator and unofficial literary agent. During the Great Purge most of Eastman's left-wing friends in the Soviet Union were executed by Stalin. Books published during this period include The Enjoyment of Laughter (1935), The End of Socialism in Russia (1937), Stalin's Russia and the Crisis in Socialism (1940), Marxism, Is It Science? (1940) and Heroes I Have Known (1942).

During the Second World War Eastman began to question his socialist beliefs. In 1941 the Reader's Digest appointed him their roving editor and began publishing his attacks on socialists and communists. He wrote: "Red Baiting - in the sense of reasoned, documented exposure of Communist and pro-Communist infiltration of government departments and private agencies of information and communication - is absolutely necessary. We are not dealing with honest fanatics of a new idea, willing to give testimony for their faith straightforwardly, regardless of the cost."

In 1952 Eastman was introduced to Alexander Orlov, a NKVD officer who had fled to the United States in 1938. Orlov had been working on a book about Joseph Stalin. Eastman agreed to be his literary agent. Eastman arranged for Orlov to meet Eugene Lyons, another former Marxist who was now a staunch anti-Communist. This led to a meeting with John S. Billings, the editor of Life Magazine. Orlov submitted his manuscript to the magazine and the first of the four articles, The Ghastly Secrets of Stalin's Power, appeared on 6th April. The article created great controversy and was discussed in great depth in the American media. With each successive installment, the circulation of the magazine reached new heights. Orlov's book, The Secret History of Stalin's Crimes, was published by Random House in the autumn of 1953.

In the 1950s Eastman was a strong supporter of Joe McCarthy and the House of Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC). His anti-Communist articles in the Reader's Digest, The Freeman and the National Review in the early 1950s played an important role in what became known as McCarthyism. In June 1953 he wrote: "Red Baiting - in the sense of reasoned, documented exposure of Communist and pro-Communist infiltration of government departments and private agencies of information and communication - is absolutely necessary. We are not dealing with honest fanatics of a new idea, willing to give testimony for their faith straightforwardly, regardless of the cost. We are dealing with conspirators who try to sneak in the Moscow-inspired propaganda by stealth and double talk, who run for shelter to the Fifth Amendment when they are not only permitted but invited and urged by Congressional committee to state what they believe. I myself, after struggling for years to get this fact recognized, give McCarthy the major credit for implanting it in the mind of the whole nation."

In 1955 he published Reflections on the Failure of Socialism. He argued: "Instead of liberating the mind of man, the Bolshevik revolution locked it into a state's prison tighter than ever before. No flight of thought was conceivable, no poetic promenade even, to sneak through the doors or peep out of a window in this pre-Darwinian dungeon called Dialectic Materialism. No one in the western world has any idea of the degree to which Soviet minds are closed and sealed tight against any idea but the premises and conclusions of this antique system of wishful thinking. So far as concerns the advance of human understanding, the Soviet Union is a gigantic road-block, armed, fortified and defended by indoctrinated automatons made out of flesh, blood and brains in robot-factories they call schools."

In 1956 Eastman wrote: "We are fighting this cold war for our life, and we must fight on all fronts and in every field of action. We must employ in a campaign to liberate the enslaved countries and deliver the world from the menace of Communist tyranny all the means employed by the Communists to destroy and enslave us-expecting only that we fight with the truth, adhering to moral principle, while they fight with lies and a deliberate code of treachery. And we must make our aim as clear to the world as the Communists have made theirs. We must never affirm our loyalty to Peace without linking to it the word Freedom."

For over twenty-five years Eastman worked as a roving reporter for the Reader's Digest where he advocated free enterprise and warned of the dangers of communism. He also wrote two volumes of autobiography: The Enjoyment of Living (1948) and Love and Revolution (1965).

In 1956 Eastman wrote: "We are fighting this cold war for our life, and we must fight on all fronts and in every field of action. We must employ in a campaign to liberate the enslaved countries and deliver the world from the menace of Communist tyranny all the means employed by the Communists to destroy and enslave us-expecting only that we fight with the truth, adhering to moral principle, while they fight with lies and a deliberate code of treachery. And we must make our aim as clear to the world as the Communists have made theirs. We must never affirm our loyalty to Peace without linking to it the word Freedom."

For over twenty-five years Eastman worked as a roving reporter for the Reader's Digest where he advocated free enterprise and warned of the dangers of communism. He also wrote two volumes of autobiography: The Enjoyment of Living (1948) and Love and Revolution (1965).

On this day in 1976 General Bernard Montgomery died. Montgomery, the son of a bishop, was born in London on 17th November 1887. He was educated at St Paul's School and Sandhurst Military Academy. He later recalled: "In 1907 entrance to the Royal Military College, Sandhurst, was by competitive examination. There was first a qualifying examination in which it was necessary to show a certain minimum standard of mental ability; the competitive examination followed a year or so later. These two hurdles were negotiated without difficulty, and in the competitive examination my place was 72 out of some 170 vacancies." After graduating in 1908 joined the Royal Warwickshire Regiment.

Montgomery served in India before being sent to France at the beginning of the First World War. He was seriously wounded when he was shot in the chest in October 1914: "My life was saved that day by a soldier of my platoon. I had fallen in the open and lay still hoping to avoid further attention from the Germans. But a soldier ran to me and began to put a field dressing on my wound; he was shot through the head by a sniper and collapsed on top of me. The sniper continued to fire at us and I got a second wound in the knee; the soldier received many bullets intended for me. No further attempt was made by my platoon to rescue us; indeed, it was presumed we were both dead. When it was dark the stretcher-bearers came to carry us in; the soldier was dead and I was in a bad way."

After a long spell in a military hospital, Montgomery returned to the Western Front in 1916 and by 1918 was chief of staff of the 47th London Division. In his autobiography Montgomery argued that: " The higher staffs were out of touch with the regimental officers and with the troops. The former lived in comfort, which became greater as the distance of their headquarters behind the lines increased. There was no harm in this provided there was touch and sympathy between the staff and the troops. This was often lacking. The frightful casualties appalled me."

Montgomery remained in the British Army and in 1926 became an instructor at Camberley. Promoted to the rank of major general he was sent to command British forces Palestine in October, 1938. On the outbreak of the Second World War Montgomery was sent to France with the British Expeditionary Force. He led the 2nd Corps but was forced to retreat to Dunkirk during Germany's Western Offensive and arrived back in England on 1st June, 1940. Montgomery was placed in command of the 5th Corps (July 1940-April 1941), the 12th Corps (April 1941-December 1941) and the South-Eastern Army (December 1941-August 1942).

In July 1942 Erwin Rommel and the Deutsches Afrika Korps were only 113km (70 miles) from Alexandria. The situation was so serious that Winston Churchill made the long journey to Egypt to discover for himself what needed to be done. Churchill decided to make changes to the command structure. General Harold Alexander was placed in charge of British land forces in the Middle East and Montgomery was chosen to become commander of the Eighth Army.

On 30th August, 1942, Erwin Rommel attacked at Alam el Halfa but was repulsed by the Eighth Army. Montgomery responded to this attack by ordering his troops to reinforce the defensive line from the coast to the impassable Qattara Depression. Montgomery was now able to make sure that Rommel and the German Army was unable to make any further advances into Egypt. Rommel reported that he was ill and was evacuated. Doctors reported that he was "suffering from chronic stomach and intestinal catarrh, nasal diphtheria and considerable circulation trouble."

Over the next six weeks Montgomery began to stockpile vast quantities of weapons and ammunition to make sure that by the time he attacked he possessed overwhelming firepower. By the middle of October the Eighth Army totalled 195,000 men, 1,351 tanks and 1,900 pieces of artillery. This included large numbers of recently delivered Sherman M4 and Grant M3 tanks.

On 23rd October, 1942, General Bernard Montgomery launched Operation Lightfoot with the largest artillery bombardment since the First World War. The attack came at the worst time for the Deutsches Afrika Korps as Erwin Rommel was on sick leave in Austria. His replacement, General George Stumme, died of a heart-attack the day after the 900 gun bombardment of the German lines. Stume was replaced by General Ritter von Thoma and Adolf Hitler phoned Rommel on 24th October: "Rommel, there is bad news from Africa. The situation looks very black. No one seems to know what has happened to Stumme. Do you feel well enough to go back and would you be willing to go?"

When Erwin Rommel returned he launched a counterattack at Kidney Depression (27th October). Montgomery now returned to the offensive and the 9th Australian Division created a salient in the enemy positions. Winston Churchill was disappointed by the Eighth Army's lack of success and accused Montgomery of fighting a "half-hearted" battle. Montgomery ignored these criticisms and instead made plans for a new offensive, Operation Supercharge.

On 1st November 1942, Montgomery launched an attack on the Deutsches Afrika Korps at Kidney Ridge. After initially resisting the attack, Rommel decided he no longer had the resources to hold his line and on the 3rd November he ordered his troops to withdraw. However, Adolf Hitler overruled his commander and the Germans were told to stand and fight.

The next day Montgomery ordered his men forward. The Eighth Army broke through the German lines and Erwin Rommel, in danger of being surrounded, was forced to retreat. Those soldiers on foot, including large numbers of Italian soldiers, were unable to move fast enough and were taken prisoner. For a while it looked like the the British would cut off Rommel's army but a sudden rain storm on 6th November turned the desert into a quagmire and the chasing army was slowed down. Rommel, now with only twenty tanks left, managed to get to Sollum on the Egypt-Libya border. On 8th November Rommel learned of the Allied invasion of Morocco and Algeria that was under the command of General Dwight D. Eisenhower. His depleted army now faced a war on two front.

The British Army recaptured Tobruk on 12th November, 1942. During the El Alamein campaign half of Rommel's 100,000 man army was killed, wounded or taken prisoner. He also lost over 450 tanks and 1,000 guns. The British and Commonwealth forces suffered 13,500 casualties and 500 of their tanks were damaged. However, of these, 350 were repaired and were able to take part in future battles. Winston Churchill was convinced that the battle of El Alamein marked the turning point in the war and ordered the ringing of church bells all over Britain. As he said later: "Before Alamein we never had a victory, after Alamein we never had a defeat."

Montgomery and the Eighth Army continued to move forward and captured Tripoli on 23rd January, 1943. Rommel was unable to mount a successful counterattack and on 9th March he was replaced by Jurgen von Arnium as commander in chief of Axis forces in Africa. This change failed to halt the Allied advance in Africa and on 11th May, 1943, the Axis forces surrendered Tunisia.

At the Casablanca Conference held in January 1943, Winston Churchill and Franklin D. Roosevelt decided to launch an invasion of Sicily. It was hoped that if the island was taken Italy might withdraw from the war. It was also argued that a successful invasion would force Adolf Hitler to send troops from the Eastern Front and help to relieve pressure on the Red Army in the Soviet Union.

The operation was placed under the supreme command of General Dwight D. Eisenhower. General Harold Alexander was commander of ground operations and his 15th Army Group included Montgomery (8th Army) and General George Patton (US 7th Army). Admiral Andrew Cunningham was in charge of naval operations and Air Marshal Arthur Tedder was air commander.

On 10th July 1943, the 8th Army landed at five points on the south-eastern tip of the island and the US 7th Army at three beaches to the west of the British forces. The Allied troops met little opposition and Patton and his troops quickly took Gela, Licata and Vittoria. The British landings were also unopposed and Syracuse was taken on the the same day. This was followed by Palazzolo (11th July), Augusta (13th July) and Vizzini (14th July), whereas the US troops took the Biscani airfield and Niscemi (14th July).

General George Patton now moved to the west of the island and General Omar Bradley headed north and the German Army was forced to retreat to behind the Simeto River. Patton took Palermo on 22nd July cutting off 50,000 Italian troops in the west of the island. Patton now turned east along the northern coast of the island towards the port of Messina.

Meanwhile Montgomery and the 8th Army were being held up by German forces under Field Marshal Albrecht Kesselring. The Allies carried out several amphibious assaults attempted to cut off the Germans but they were unable to stop the evacuation across the Messina Straits to the Italian mainland. This included 40,000 German and 60,000 Italian troops, as well as 10,000 German vehicles and 47 tanks.

On 17th August 1943, General George Patton and his troops marched into Messina. The capture of Sicily made it possible to clear the way for Allied shipping in the Mediterranean. It also helped to undermine the power of Benito Mussolini and Victor Emmanuel III forced him to resign.

Montgomery, as commander of the 8th Army, led the invasion of Italy on 3rd September, 1943. When he landed at Reggio he experienced little resistance and later that day British warships landed the 1st Parachute Division at Taranto. Six days later the US 6th Corps arrived at Salerno. These troops faced a heavy bombardment from German troops and the beachhead was not secured until 20th September.

The German Army fought ferociously in southern Italy and the Allied armies made only slow progress as the moved north towards Rome. The 5th Army took Naples on 1st October and later that day the 8th Army captured the Foggia airfields.

In December 1943, Montgomery was appointed head of the 2nd Army and commander of all ground forces in the proposed invasion of Europe. Montgomery believed he was better qualified than General Dwight Eisenhower to have been given overall control of Operation Overlord. However, as the United States provided most of the men, material and logistical support, Winston Churchill was unable to get the decision changed.

Soon after the D-Day invasion Montgomery ptoposed Operation Market-Garden. The combined ground and airborne attack was designed to gain crossings over the large Dutch rivers, the Mass, Waal and Neder Rijn, to aid the armoured advance of the British 2nd Army. On 17th September 1944, three divisions of the 1st Allied Airbourne Corps landed in Holland. At the same time the British 30th Corps advanced from the Meuse-Escaut Canal. The bridges at Nijmegen and Eindhoven were taken but a German counter-attack created problems at Arnhem. Of the 9,000 Allied troops at Arnhem, only 2,000 were left when they were ordered to withdraw across the Rhine on 25th September.

After the failure of Operation Market-Garden Montgomery began to question the strategy developed by Eisenhower and as a result of comments made at a press conference he gave on 7th January, 1945, he was severely rebuked by Winston Churchill and General Alan Brooke, the head of the British Army.

Although he came close to being sacked Montgomery was allowed to remain in Europe and the end of the war was appointed Commander in Chief of the British Army of Occupation.

In 1946 Montgomery was granted a peerage and he took the title Viscount Montgomery of Alamein. He also served under General Dwight Eisenhower as deputy supreme commander of the Allied forces in Europe.

General Bernard Montgomery wrote several books on his war experiences including El Alamein to the River Sangro(1948), The Memoirs of Field Marshal Montgomery (1958), An Approach to Sanity (1959), The Path to Leadership (1961), Normandy to the Baltic (1968) and A Consise History of Warfare (1972) .