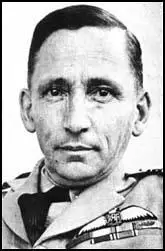

Arthur Tedder

Arthur Tedder, the son of a civil servant, was born in Glenguin, Scotland, on July, 1890. Educated at Magdalene College, Cambridge, he won the Prince Consort Prize for History in 1913.

A member of the Special Reserve of the Dorset Regiment, he joined the Royal Flying Corps in 1916. After carrying out bombing and reconnaissance missions he was given command of 70 Squadron.

Tedder joined the Royal Air Force after the war and in 1929 joined the RAF Staff College at Cranston. Other posts include head of the Air Armament School (1934-36), Director of training at the Air Ministry (1936-38) and Air Officer Commander in Singapore (1936-38).

Promoted to vice marshall Tedder was appointed director general of Research and Development in the Air Ministry in 1938. He held this post until he became air commander in the Middle East in 1940 and played an important role in the defeat of Erwin Rommel in the Desert War.

After the successful conquest of Tunisia and Sicily he was appointed as deputy Supreme Allied Commander under General Dwight Eisenhower. The two men worked closely together in planning the D-Day landings in the summer of 1944. Tedder was responsible for providing tactical air support and was a strong advocate of destroying Germany's communication system during the invasion.

Tedder's views brought him into conflict with Arthur Harris, Trafford Leigh-Mallory and Carl Spaatz. The British prime minister, Winston Churchill, who considered Tedder to be too much under the influence of the Americans, also had doubts about the wisdom of carrying out heavy bombing raids on France before the invasion.

In January 1945 Tedder met Joseph Stalin to discuss the war against Germany and on 8th May 1945 he led the Allied delegation to Berlin that accepted the surrender of the government of Nazi Germany. Tedder became Chief of the Air Staff in 1946.

After his retirement from the Royal Air Force in 1950 Tedder, now the Ist Baron of Glenquin, was chairman of the British Joint Services Commission in Washington before becoming Chancellor of Cambridge University. Arthur Tedder, who published his memoirs With Prejudice in 1966, died in Surrey on 3rd June, 1967.

Primary Sources

(1) Bernard Montgomery worked very closely with Arthur Tedder during the Desert War. He commented on the importance of air support during modern battles in 1943.

I believe that the first and great principle of war is that you must first win your air battle before you fight your land and sea battle. If you examine the conduct of the campaign from Alamein through Tunisia, Sicily and Italy you will find I have never fought a land battle until the air battle has been won. We never had to bother about the enemy air, because we won the air battle first.

The second great principle is that Army plus Air has to be so knitted that the two together from one entity. If you do that, the resultant military effort will be so great that nothing will be able to stand against it.

The third principle is that the Air Force command. I hold that it is quite wrong for the soldier to want to exercise command over the air striking forces. The handling of an Air Force is a life-study, and therefore the air part must be kept under Air Force command.

The Desert Air Force and the Eighth Army are one. We do not understand the meaning of "army cooperation". When you are one entity you cannot cooperate. If you knit together the power of the Army on the land and the power of the Air in the sky, then nothing will stand against you and you will never lose a battle.

(2) Arthur Harris, wrote about Arthur Tedder's role in the Desert War and Operation Overlord in his autobiography, Bomber Command (1947)

The plan of the campaign was worked out by the competent authorities in Shaef-Supreme Headquarters Allied Expeditionary Force. It was entirely the conception of Tedder, who certainly has one of the most brilliant minds in any of the services, and it was forced through against continuous opposition, some of which was based on the fear that it would turn the French against us. There was, of course, no reason to believe that the bombing would be as accurate as it proved to be, and I myself doubted whether we could achieve the extraordinary precision needed if the project was to succeed. It was Tedder, and the men under him, who saved the British Army in the Middle East when Rommel was threatening Egypt, and then did so much to make El Alamein a victory. In the invasion of Italy, Elsenhower saw what a great commander he was. It was, of course, of the greatest importance that the Deputy Supreme Commander should come from the Air Force, since air power would be dominant in any combined campaign. It was at one time suggested that the Deputy should come from the British Army, but Elsenhower knew both Tedder's worth and the importance of the weapons he understood so well, and insisted on his appointment and his retention of it. In such matters there was often the difficulty that Air Ministry regulations were so contrived that R.A.F. Commanders-in-the-Field were invariably outranked by those who held similar positions in other services. To the working out of the plan of campaign for the disorganization of the French railways, Tedder brought a genuinely scientific mind, with all the detachment of the scientist.

(3) Winston Churchill had doubts about the plans proposed by Arthur Tedder to carry out heavy bombing raids on France before the Normandy landings. He wrote to Franklin D. Roosevelt about this issue on 7th May, 1944.

I ought to let you know that the War Cabinet is unanimous in its anxiety about these French slaughters, even reduced as they have been, and also in its doubts as to whether almost as good military results could not be produced by other methods. Whatever is settled between us, we are quite willing to share responsibilities with you.

(4) General Dwight D. Eisenhower, diary entry (11th June, 1943)

Air Chief Marshal Sir Arthur William Tedder. He ranks close to Admiral Cunningham in qualifications, except in the one thing of broad vision. I believe that the history of the establishment of the Royal Air Force is reflected somewhat in his way of thinking and that, therefore, he is not quite as broad-gauged as he might be. I do not register this opinion as a fixed conclusion, but I sometimes have the feeling I have just expressed. Certainly in all matters of energetic operation, fitting into an allied team, and knowledge of his job, he is tops. Moreover, he is a leader type.

(5) Franklin D. Roosevelt, letter to Winston Churchill about the bombing of France (11th May, 1944)

I share fully with you your distress at the loss of life among the French population. However regrettable the attendant loss of civilian lives is, I am not prepared to impose from this distance any restriction on military action by the responsible commanders that in their opinion might militate against the success of Overlord or cause additional loss of life to our Allied forces of invasion.