On this day on 21st December

On this day in 1120 Thomas Becket, the only son of Gilbert Becket, a wealthy Norman merchant living in London, and his wife Matilda, was born. Four daughters of the marriage also survived into adulthood. His father served a term as sheriff of the City, but later he suffered heavy losses when his properties were destroyed by fire.

According to Frank Barlow "between 1130 and 1141, he was successively, but perhaps intermittently, a boarder at the Augustinian priory at Merton in Surrey, a pupil at one or more of the London grammar schools and a student at Paris."

It is claimed by Edward Grim that in his youth he was more interested in rural sports than in his books and that his way of life was frivolous. He also came under the influence of an important Norman baron, Richer de l'Aigle, a great-grandson of a knight killed at the Battle of Hastings, and himself a soldier of considerable experience. He used to take Becket on holidays into the country, where they hunted and hawked.

One of his biographers has pointed out: "His contemporaries described Thomas as a tall and spare figure with dark hair and a pale face that flushed in excitement. His memory was extraordinarily tenacious and, though neither a scholar nor a stylist, he excelled in argument and repartee. He made himself agreeable to all around him, and his biographers attest that he led a chaste life."

Thomas entered adult life as a city clerk and accountant in the service of the sheriffs. After three years he was introduced by his father to Theobald of Bec, the Archbishop of Canterbury. In 1141 he became a member of the household. His colleagues were a distinguished company that included the political philosopher John of Salisbury. Theobald was impressed with Becket and was sent to study civil and canon law at Bologna University.

It is claimed that Becket was endowed with, or acquired, most of the qualities that make for worldly success. "His elegance was enhanced by vivacity.... He had excellent manners and was a good talker. Clearly he had the ability and the will to please: he was a charmer. John of Salisbury says that he had very acute senses of smell and hearing and a good memory. Such endowments make a little education go a very long way. He was undoubtedly intelligent, alert, responsive. Once he realized that he had to make his own way he became extremely ambitious."

When Henry II became king in 1154, he asked Archbishop Theobald for advice on choosing his government ministers. On the suggestion of Theobald, Henry appointed Thomas Becket, who was twelve years his junior, as his chancellor. Becket's job was an important one as it involved the distribution of royal charters, writs and letters. People declared that "they had but one heart and one mind". The king and Becket soon became close friends. "Often the king and his minister behaved like two schoolboys at play."

William FitzStephen tells the story of Becket and the king riding together through the streets of London. It was a cold day and when the king noticed an old man coming towards them, poor and clad in a thin and ragged coat. "Do you see that man? How poor he is, how frail, and how scantily clad! Would it not be an act of charity to give him a thick warm cloak." Becket agreed and the king replied: "You shall have the credit for this act of charity" and then attempted to strip his chancellor of his new "scarlet and grey" cloak. After a brief struggle Becket reluctantly allowed the king to overcome him. "The king then explained what had happened to his attendants and they all laughed loudly".

When Theobald of Bec died in 1162, Henry chose Becket as his next Archbishop of Canterbury. The decision angered many leading churchmen. They pointed out that Becket had never been a priest, and had a reputation as a cruel military commander when he fought against the French king Louis VII. It was claimed that "who can count the number of persons he (Becket) did to death, the number whom he deprived of all their possessions... he destroyed cities and towns, put manors to the torch without thought of pity."

Becket was also very materialistic (he loved expensive food, wine and clothes). His critics also feared that as Becket was a close friend of Henry II, he would not be an independent leader of the church. At first Becket refused the post: "I know your plans for the Church, you will assert claims which I, if I were archbishop, must needs oppose." Henry insisted and he was ordained priest on 2nd June, 1162, and consecrated bishop the next day.

Herbert of Bosham claims that after being appointed as archbishop, Thomas Becket began to show a concern for the poor. Every morning thirteen poor people were brought to his home. After washing their feet Becket served them a meal. He also gave each one of them four silver pennies. John of Salisbury believed that Becket sent food and clothing to the homes of the sick, and that he doubled Theobald's expenditure on the poor.

Instead of wearing expensive clothes, Becket now wore a simple monastic habit. As a penance (punishment for previous sins) he slept on a cold stone floor, wore a tight-fitting hairshirt that was infested with fleas and was scourged (whipped) daily by his monks. As a contemporary wrote: "Clad in a hair-shirt of the roughest kind which reached to his knees and swarmed with vermin, he punished his flesh with the sparest diet, and his main drink was water... He often exposed his naked back to the lash."

John Gillingham has argued that Becket had responded to the criticism his appointment had received: "In the eyes of respectable churchmen Becket... he did not deserve to be archbishop. He was too wordly and too much the King's friend. Wounded in his self-esteem Becket set out to prove, to an astonished world, that he was the best of all possible archbishops. Right from the start he went out of his way to oppose the King who, chiefly out of friendship, had made him an archbishop."

Thomas Becket soon came into conflict with Roger of Clare, Earl of Hertford. Becket argued that some of the manors in Kent should come under the control of the Archbishop of Canterbury. Roger disagreed and refused to give up this land. Becket sent a messenger to see Roger with a letter asking for a meeting. Roger responded by forcing the messenger to eat the letter.

In January, 1163, after a long spell in France, Henry II arrived back in England. Henry was told that, while he had been away, there had been a dramatic increase in serious crime. The king's officials claimed that over a hundred murderers had escaped their proper punishment because they had claimed their right to be tried in church courts. Those that had sought the privilege of a trial in a Church court were not exclusively clergymen. Any man who had been trained by the church could choose to be tried by a church court. Even clerks who had been taught to read and write by the Church but had not gone on to become priests had a right to a Church court trial. This was to an offender's advantage, as church courts could not impose punishments that involved violence such as execution or mutilation. There were several examples of clergy found guilty of murder or robbery who only received "spiritual" punishments, such as suspension from office or banishment from the altar.

The king decided that clergymen found guilty of serious crimes should be handed over to his courts. At first, the Archbishop agreed with Henry on this issue and in January 1164, Henry published the Clarendon Constitution. After talking to other church leaders Becket changed his mind. Henry was furious when Becket began to assert that the church should retain control of punishing its own clergy. The king believed that Becket had betrayed him and was determined to obtain revenge.

In 1164, the Archbishop of Canterbury was involved in a dispute over land. Henry ordered Becket to appear before his courts. When Becket refused, the king confiscated his property. Henry also claimed that Becket had stolen £300 from government funds when he had been Chancellor. Becket denied the charge but, so that the matter could be settled quickly, he offered to repay the money. Henry refused to accept Becket's offer and insisted that the Archbishop should stand trial. When Henry mentioned other charges, including treason, Becket decided to run away to France.

Becket joined his former secretary, John of Salisbury in Rheims: The two men were very close friends: "John of Salisbury, a small and delicate man, warm, lively and playful, a joker with an eye to the ridiculous, the confident member of a learned elite, so sure of his scholarship that he could quote, to amuse his circle, classical authors and other embroideries of his own invention, was everything that Thomas Becket was not."

However, the quarrel between Becket and the king put a strain upon their friendship: John would not abandon Becket's cause but he disagreed with the way Becket was dealing with the situation. Becket now moved to Pontigny Abbey. According to Edward Grim, at least three times a day, his chaplain, was compelled by Becket, to "scourge him on the bare back until the blood flowed". Grim added that with these punishments he "killed all carnal desires".

Under the protection of Henry's old enemy. King Louis VII, Becket organised a propaganda campaign against the monarchy. As Becket was supported by Pope Alexander III, Henry feared that he would be excommunicated (expelled from the Christian Church). Alexander sent a letter to Henry urging him to make peace with Becket and suggesting that he restored him as Archbishop of Canterbury.

John of Salisbury was also involved in negotiations with Henry II and Louis VII. The three men met at Angers in April 1166. In a letter to Becket he complained that he wasted money and lost two horses on the journey and that it obtained nothing of value. Talks continued and on 7th January 1169, Becket and Henry met at Montmirail but they failed to reach an agreement. Alexander, finally ran out of patience and ordered Becket to agree a deal with Henry. On 22nd July, 1170, Becket and Henry met at Fréteval and it was agreed that the archbishop should return to Canterbury and receive back all the possessions of his see.

On his arrival, Thomas Becket excommunicated (expelled from the Christian Church) Roger de Pont L'Évêque, the Archbishop of York, and other leading churchmen who had supported the king while he was away. Henry II, who was in Normandy at the time, was furious when he heard the news. Guernes de Pont-Sainte-Maxence, claims he said: "A man who has eaten my bread, who came to my court poor and I have raised him high - now he draws up his heel to kick me in the teeth! He has shamed my kin, shamed my realm: the grief goes to my heart, and no one has avenged me!"

Edward Grim points out that Henry added: "What miserable drones (the male of the honeybee that is stingless) and traitors have nourished and promoted in my realms, who let their lord to be treated with such shameful contempt by a low-born clerk." (25) According to Gervase of Canterbury the king said: "How many cowardly, useless drones have I nourished that not even a single one is willing to avenge me of the wrongs I have suffered." Four of Henry's knights, Hugh de Morville, William de Tracy, Reginald FitzUrse, and Richard Ie Breton, who heard Henry's angry outburst decided to travel to England to see Becket.

When the knights arrived at Canterbury Cathedral on 29th December 1170, they demanded that Becket pardon the men he had excommunicated. Edward Grim later reported: "The wicked knight (William de Tracy), fearing that the Archbishop would be rescued by the people in the nave... wounded this lamb who was sacrificed to God... cutting off the top of the head... Then he received a second blow on his head from Reginald FitzUrse but he stood firm. At the third blow he fell on his knees and elbows... Then the third knight (Richard Ie Breton) inflicted a terrible wound as he lay, by which the sword was broken against the pavement... the blood white with the brain and the brain red with blood, dyed the surface of the church. The fourth knight (Hugh de Morville) prevented any from interfering so the others might freely murder the Archbishop."

Benedict of Peterborough, a prior based in Canterbury, wrote about what he knew about the murder: "While the body still lay on the pavement... some of them (people from Canterbury) brought bottles and carried off secretly as much blood as they could. Others cut off shreds of clothing and dipped them in the blood. Some of the blood left over was carefully collected and poured into a clean vessel... They stripped him of his outer garments... and in doing so they discovered that the body was covered in sackcloth, even from the thighs down to the knees."

Arnulf, the Bishop of Lisieux, was with Henry II when he heard the news of Becket's death. In a letter to Alexander III he wrote: "The king burst into loud cries and exchanged his royal robes for sackcloth... For three whole days he remained shut up in his chamber, and would neither take food nor admit anyone to comfort him." William of Blois also wrote to the Pope about the murder. "I have no doubt that the cry of the whole world has already filled your ears of how the king of the English, that enemy of the angels... has killed the holy one... For all the crimes we have ever read or heard of, this easily takes first place - exceeding all the wickedness of Nero."

Pope Alexander III canonised Becket on 21st February, 1173 and he became a symbol of Christian resistance to the power of the monarchy. The king met Alexander III's legates at Avranches in May and submitted to their judgment. An agreement was signed on 21st May, 1172, that included the following: "That he (Henry) should at his own expense provide two hundred knights to serve for a year with the Templers in the Holy Land. That he himself should take the cross for a period of three years and depart for the Holy Land before the following Easter. That he should utterly abolish customs damaging to the Church which had been introduced in his reign."

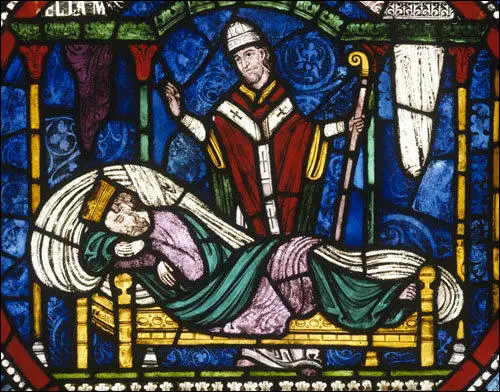

Henry admitted that, although he never desired the killing of Becket, his words may have prompted the murderers. On 12th July, 1174, Henry II did public penance, and was scourged at the archbishop's tomb. The event was described by Gervase of Canterbury: "He (Henry II) set out with a sad heart to the tomb of St. Thomas at Canterbury... he walked barefoot and clad in a woollen smock all the way to the martyr's tomb. There he lay and of his free will was whipped by all the bishops and abbots there present and each individual monk of the church of Canterbury."

In the Middle Ages the Church encouraged people to make pilgrimages to special holy places called shrines. It was believed that if you prayed at these shrines you might be forgiven for your sins and have more chance of going to heaven. Others went to shrines hoping to be cured from an illness they were suffering from. Becket's tomb at Canterbury Cathedral became the most popular shrine in England. When Becket was murdered local people managed to obtain pieces of cloth soaked in his blood. Rumours soon spread that, when touched by this cloth, people were cured of blindness, epilepsy and leprosy. It was not long before the monks at Canterbury Cathedral were selling small glass bottles of Becket's blood to visiting pilgrims. The monks also sold metal badges that had been stamped with the symbol of the shrine. The badges were then fixed to the pilgrim's hat so that people would know they had visited the shrine.

On this day in 1804 Benjamin Disraeli, the eldest son and second of five children of Isaac D'Israeli and his wife, Maria Basevi Disraeli, was born at 6 King's Road, Bedford Row, London, on 21st December 1804. His father was a historian and literary critic. In 1816 he inherited a large fortune of the death of his father, Benjamin D'Israeli, a successful businessman.

Disraeli was brought up in the Jewish faith but was baptized into the Christian faith on 31st July 1817. He attended Higham Hall in Epping Forest, a school run by the Unitarian minister Eli Cogan, until 1819, after which he was taught at home.

In November 1821 Disraeli was articled at his father's arrangement to a solicitor's firm in the Old Jewry. His name was entered at Lincoln's Inn, but rejected the idea of a career at the bar because he had a strong dislike of the mundane lifestyle of the English middle classes, who he claimed the "only adventure of life" was marriage.

An ardent admirer of Lord Byron, he dreamed instead of literary fame. "From the early 1820s he had adopted an appropriately eye-catching and narcissistic style of dress, with ruffled shirts, velvet trousers, coloured waistcoats, and jewellery, and he wore his hair in cascades of ringlets... He reflected self-consciously, in Romantic fashion, on the sublime natural creations that he observed on his travels."

Disraeli's first novel, Vivian Grey was published anonymously in two volumes in April 1826. It was a portrayal of the unscrupulous ambition of a clever young man. It was also highly critical of London society. It received some very bad reviews and when the identity of the author was revealed, it did his reputation a great deal of harm. However, the book sold very well and it made it possible for him to become a full-time author.

The literary abuse he received "contributed to the onset of a major nervous crisis that affected him for much of the next four years... he had always been moody, sensitive, and solitary by nature, but now became seriously depressed and lethargic." (5) Disraeli continued to write and his first success was followed by The Young Duke (1831), Contarini Fleming (1832), Alroy (1833), Henrietta Temple (1837) and Venetia (1837).

Benjamin Disraeli took a strong interest in politics and was advocate of parliamentary reform. He refused to support the Tories or the Whigs. "Toryism is worn out & I cannot condescend to be a Whig." In the 1832 General Election he stood as a Radical at High Wycombe. Despite having the support of the two leading progressives, Francis Burdett and Daniel O'Connell, he was defeated, by the Whig candidate.

In 1833, Disraeli published a pamphlet where he argued for a Tory–Radical coalition against the Whigs. When he stood in the High Wycombe seat in the 1835 General Election he stood as an Independent Radical, he was supplied with £500 from Tory funds. This was the first time that the Tories had used money is this way and the historian, Robert Blake, has suggested that this marks the start of the modern Conservative Party. Again he was heavily defeated and later that year he fought the Taunton by-election as a Tory. Once again he was defeated but over the next few months he concentrated on producing Tory propaganda.

Disraeli's change in political affiliations upset the Radicals and his old friend, Daniel O'Connell, launched a bitter attack: "After being twice discarded by the people, to become a Conservative. He possesses all the necessary requisites of perfidy, selfishness, depravity, want of principle, etc., which would qualify him for the change. His name shows that he is of Jewish origin. I do not use it as a term of reproach; there are many most respectable Jews. But there are, as in every other people, some of the lowest and most disgusting grade of moral turpitude; and of those I look upon Mr. Disraeli as the worst."

Benjamin Disraeli responded by attacking O'Connell in The Times newspaper. This included a demand for a duel with O'Connell's son. As a result of this Disraeli was arrested. This dispute helped to promote Disraeli's political career and he was offered the safe Tory seat of Maidstone. Disraeli easily beat his Whig opponent in the 1837 General Election.

Disraeli's maiden speech in the House of Commons was poorly received and after enduring a great deal of barracking ended with the words: "though I sit down now, the time will come when you will hear me." Disraeli advocated triennial parliaments and the secret ballot. In one speech argued that the "rights of labour were as sacred as the rights of property". In another he spoke against the Poor Law Amendment Act, something that he described as the "more odious than any other new Bill since the Conquest".

Disraeli advocated parliamentary reform and joined those such as Thomas Attwood, Thomas Wakely, Thomas Duncombe, John Fielden and Joseph Hume, who supported Moral Force Chartism. Disraeli believed that peaceful methods of persuasion such as the holding of public meetings, the publication of newspapers and pamphlets and the presentation of petitions to Parliament would finally convince the government to reform the parliamentary system.

Disraeli argued that moderate reform would undermine people like Feargus O'Connor, James Rayner Stephens and George Julian Harney, who were the leaders of the Physical Force Chartists. O'Connor began making speeches where he spoke of being willing "to die for the cause" and promising to "lead people to death or glory". O'Connor argued that the concessions the chartists demanded would not be conceded without a fight, so there had to be a fight. In July 1839, Disraeli spoke up persuasively for the arguments in the Chartist petition - and then joined the 235 MPs who voted to reject it.

On 28th August 1839, Benjamin Disraeli married Mary Anne Lewis, the widow of Wyndham Lewis, the Tory MP who had died the previous year. Aged 47 she was extremely wealthy. On one occasion Disraeli remarked that he had married for money, and his wife replied, "Ah! but if you had to do it again, you would do it for love."

According to Jonathan Parry: "She was coquettish, impulsive, not well educated, and extremely talkative, but also warm, loyal, and sensible. She shared something of Disraeli's love of striking clothes and social glitter while feeling, like him, an outsider in very high social circles. Her money, house, and solid position were undoubtedly attractive to him... . But so also were her vivacity and her childless motherliness. All his life older women appealed to Disraeli, apparently in search of a mother-substitute more appreciative of his genius than his own stolid parent had been... She provided the domestic stability and constant admiration that he sorely needed. She also paid off many of his debts: she had spent £13,000 on these and his elections."

After the Conservative victory in the 1841 General Election, Disraeli suggested to Sir Robert Peel, the new Prime Minister, that he would make a good government minister. Peel disagreed and Disraeli had to remain on the backbenches. Disraeli was hurt by Peel's rejection and over the next few years he became a harsh critic of the Conservative government. As Duncan Watts pointed out: "Peel was to pay a heavy price for Disraeli's wounded pride."

In 1842 Disraeli helped to form the Young England group. Disraeli and members of his group argued that the middle class now had too much political power and advocated an alliance between the aristocracy and the working class. Disraeli suggested that the aristocracy should use their power to help protect the poor. This political philosophy was expressed in Disraeli's novels Coningsby (1844), Sybil (1845) and Tancred (1847). In these books the leading characters show concern about poverty and the injustice of the parliamentary system.

Robert Blake argues that Disraeli had no chance of making this the policy of the Conservative Party, as its vast majority of members were committed to preserving the status quo. "To give the vote to the starving, illiterate, semi-revolutionary masses, victims of every sort of delusion from Chartism downwards, would have seemed lunacy to the possessing classes. Rightly or wrongly they had no intention of risking it, and that fact alone ruled Tory-Radicalism out of the realm of practical politics".

Peel attempted to overcome the religious conflict in Ireland by setting up the Devon Commission to inquire into the "state of the law and practice in respect to the occupation of land in Ireland." However, Peel's attempts to improve the situation in Ireland was severely damaged by the 1845 potato blight. The Irish crop failed, therefore depriving the people of their staple food. Peel was informed that three million poor people in Ireland who had previously lived on potatoes would require cheap imported corn. Peel realised that they only way to avert starvation was to remove the duties on imported corn.

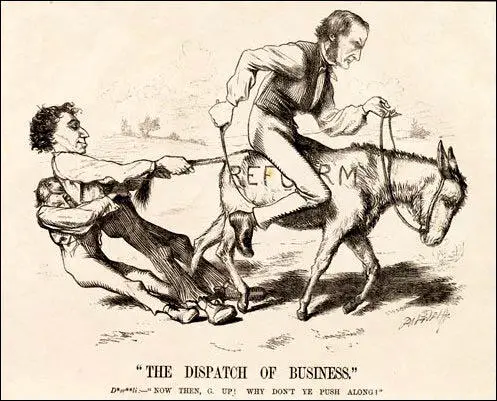

The first months of 1846 were dominated by a battle in Parliament between the free traders and the protectionists over the repeal of the Corn Laws. Disraeli became the leader of the group that opposed Peel. He was accused of using this difficult situation to undermine the Prime Minister. However, he later told a fellow MP that he did this "because, from my earliest years, my sympathies had been with the landed interest of England". Disraeli made a stinging attack on Peel when he accusing him of betraying "the independence of party" and thus "the integrity of public men, and the power and influence of Parliament itself".

An alliance of free-trade Conservatives (Peelites), Radicals, and Whigs assured the repeal of the Corn Laws. However, it caused a slit in the Conservative Party. "It was not a straight division of landed gentry against the rest. It was a division between those who considered that the retention of the corn laws was an essential bulwark of the order of society in which they believed and those who considered that the Irish famine and the Anti-Corn Law League had made retention even more dangerous to that order than abandonment."

Sir Robert Peel resigned as Prime Minister in June 1846. The Tories were so divided that they were unable to form a government. Queen Victoria sent for Lord John Russell, the Whig leader. In the 1847 General Election, Disraeli stood, successfully, for the Buckinghamshire constituency. The new House of Commons had more Conservatives (325) than Whigs (292), but the depth of the Tory schism enabled Russell to continue to govern.

The Conservatives were now officially led by George Bentinck in the Commons but Disraeli was seen as the rising star. He began to change his image in Parliament: "The colourful attire had by now given way to the black frock coat (sometimes blue in summer), grey trousers, plush waistcoat, and sober neckerchief which was to be his Commons uniform for the next thirty years. He worked hard on his oratory, mugging up blue books and spending all day memorizing figures... He capitalized on his clear voice, great command of language, and extraordinarily retentive memory, and now began to learn the art of managing parliamentary debates tactically". One observer stated that because of the damage caused by the split in the Tory Party, Disraeli "was like a subaltern in a great battle where every superior officer was killed or wounded".

In 1847, Lionel de Rothschild had been returned as the MP for the City of London. As a practising Jew he could not take the oath of allegiance in the prescribed Christian form, and therefore could not take his seat. Lord John Russell proposed in the Commons that the oath should be amended to permit Jews to enter Parliament. Disraeli spoke in favour of the measure, arguing that Christianity was "completed Judaism".

The speech was badly received by his own party. The Anglican establishment disagreed with the proposal and Samuel Wilberforce, Bishop of Oxford, suggested that Lord Russell was paying off the Jews for helping elect him. The bill did get through the House of Commons but was defeated in the House of Lords. Rothschild was several times elected but had to wait another eleven years to be allowed into Parliament.

On 4th February, 1852, Lord John Russell, the leader of the Whig government, resigned. Edward Smith-Stanley, 14th Earl of Derby, the new Prime Minister, appointed Disraeli as his Chancellor of the Exchequer. It has been claimed that Disraeli was attracted to the office by the £5,000 per year salary, which helped pay his debts.

Benjamin Disraeli recognized that a return to the Corn Laws was politically impossible as he feared it would result in social unrest. He therefore attempted to help the landed interests in other ways. Disraeli proposed various fiscal remedies, principally rate relief for agriculture, but also malt tax reduction and income tax differentiation in favour of tenant farmers. This period of power only lasted a few months and Derby was soon replaced as Prime Minister by George Hamilton-Gordon, 4th Earl of Aberdeen.

Lord Derby became Prime Minister again in 1858 and once again Disraeli was appointed as Chancellor of the Exchequer. He also became leader of the House of Commons and was responsible for the introduction of measures to reform parliament. In February, 1858, Disraeli proposed the equalization of the town and county franchise. This would have resulted in some men in towns losing the vote and was opposed by the Liberals. An amendment proposed by Lord John Russell "condemning this disfranchisement" was passed by 330 to 291.

Derby dissolved Parliament, and the ensuing 1859 General Election resulted in modest Tory gains, but not enough to control the House of Commons. Derby resigned, and Lord Palmerston, became Prime Minister, and Disraeli once more lost his position in the government. In March 1860 Lord John Russell attempted to introduce a new Parliamentary Reform Act that would reduce the qualification for the franchise to £10 in the counties and £6 in towns, and effecting a redistribution of seats. Palmerson was opposed to parliamentary reform, and with his lack of support, the measure did not become law.

William Gladstone, the new leader of the Liberal Party, made it clear that like Lord Russell, he was also in favour of increasing the number of people who could vote. Although the Conservative Party had opposed previous attempts to introduce parliamentary reform, Lord Derby's new government were now sympathetic to the idea. The Conservatives knew that if the Liberals returned to power, Gladstone was certain to try again. Disraeli "feared that merely negative and confrontational responses to the new forces in the political nation would drive them into the arms of the Liberals and promote further radicalism" and decided that the Conservative Party had to change its policy on parliamentary reform.

Benjamin Disraeli argued that the Conservatives were in danger of being seen as an anti-reform party. In 1867 Disraeli proposed a new Reform Act. Robert Gascoyne-Cecil, (later 3rd Marquess of Salisbury) resigned in protest against this extension of democracy. However, as he explained this had nothing to do with democracy: "We do not live - and I trust it will never be the fate of this country to live - under a democracy."

On 21st March, 1867, William Gladstone made a two hour speech in the House of Commons, exposing in detail the inconsistencies of the bill. On 11th April Gladstone proposed an amendment which would allow a tenant to vote whether or not he paid his own rates. Forty-three members of his own party voted with the Conservatives and the amendment was defeated. Gladstone was so angry that apparently he contemplated retirement to the backbenches.

However, Disraeli did accept an amendment from Grosvenor Hodgkinson, which added nearly half a million voters to the electoral rolls, therefore doubling the effect of the bill. Gladstone commented: "Never have I undergone a stronger emotion of surprise than when, as I was entering the House, our Whip met me and stated that Disraeli was about to support Hodgkinson's motion."

On 20th May 1867, John Stuart Mill, the Radical MP for Westminster, and the leading male supporter in favour of women's suffrage, proposed that women should be granted the same rights as men. "We talk of political revolutions, but we do not sufficiently attend to the fact that there has taken place around us a silent domestic revolution: women and men are, for the first time in history, really each other's companions... when men and women are really companions, if women are frivolous men will be frivolous... the two sexes must rise or sink together."

During the debate on the issue, Edward Kent Karslake, the Conservative MP for Colchester, said in the debate that the main reason he opposed the measure was that he had not met one woman in Essex who agreed with women's suffrage. Lydia Becker, Helen Taylor and Frances Power Cobbe, decided to take up this challenge and devised the idea of collecting signatures in Colchester for a petition that Karslake could then present to parliament. They found 129 women resident in the town willing to sign the petition and on 25th July, 1867, Karslake presented the list to parliament. Despite this petition the Mill amendment was defeated by 196 votes to 73. Gladstone voted against the amendment.

Other amendments were accepted: Out went the "dual vote" which allowed people with property to vote in town and country. The clause that would give extra votes for people with savings or education. So did the requirement that ratepayers would need to show two years' residence - the condition was reduced to one year. Robert Cecil, 3rd Marquis of Salisbury, complained that "all the precautions, guarantees, and securities in the Bill" had disappeared. He told Disraeli: "You are afraid of the pot boiling over. At the first threat of battle you throw your standard in the mud".

Benjamin Disraeli dismissed these points by right-wing members of his party, by claiming that this reform will guarantee peace in the years to come: "England is safe in the race of men who inhabit her, safe in something much more precious than her accumulated capital - her accumulated experience. She is safe in her national character, in her fame and in that glorious future which I believe awaits her."

William Gladstone decided not to take part in the debate on the third reading of the bill as he feared it would have a negative reaction: "A remarkable night. Determined at the last moment not to take part in the debate: for fear of doing mischief on our own side." Without provocation from Gladstone the bill was passed without division. The House of Lords also agreed to pass the 1867 Reform Act.

The 1867 Reform Act gave the vote to every male adult householder living in a borough constituency. Male lodgers paying £10 for unfurnished rooms were also granted the vote. This gave the vote to about 1,500,000 men. The Reform Act also dealt with constituencies and boroughs with less than 10,000 inhabitants lost one of their MPs. The forty-five seats left available were distributed by: (i) giving fifteen to towns which had never had an MP; (ii) giving one extra seat to some larger towns - Liverpool, Manchester, Birmingham and Leeds; (iii) creating a seat for the University of London; (iv) giving twenty-five seats to counties whose population had increased since 1832.

On 27th February, Edward Smith-Stanley, 14th Earl of Derby, retired as prime minister on medical advice, and was replaced by Benjamin Disraeli. A few days later William Gladstone, the leader of the Liberal Party, moved and carried a bill to abolish compulsory church rates, an issue which united radicals, libertarians, nonconformists and those Anglicans unwilling to defend the status-quo. Gladstone followed this by carrying with a majority of sixty-five votes the first of three resolutions to abolish the Anglican establishment in Ireland. By taking this action Gladstone was able to heal the divisions in the Liberal Party, that had been divided over the issue of parliamentary reform.

Gladstone later argued that the decision publicly to advocate Irish disestablishment was an example of "a striking gift" endowed on him by Providence, which enabled him to identify a question whose moment for public discussion and action had come. Henry Labouchere , a fellow Liberal MP, responded by saying that he "did not object to the old man always having a card up his sleeve, but he did object to his insinuating that the Almighty had placed it there."

More than a million votes were cast in the 1868 General Election. This was nearly three times the number of people who voted in the previous election. The Liberals won 387 seats against the 271 of the Conservatives. Robert Blake believes the Irish issue was an important factor in Gladstone's victory. "Gladstone could not have selected a better issue on which to unify his own party and divide his opponents". The Liberals did especially well in the cities because of the "existence of a large Irish immigrant population".

Out of office Disraeli resumed his career as a novelist. As Duncan Watts has pointed out: "Generally he was content to sit back and allow his arch enemy to make mistakes, and there was some dissatisfaction within the Party at his lack of positive leadership. Attempts were made to replace him with the Earl of Derby, son of the old Prime Minister, but he withstood the challenge."

When the Conservatives were in power they had established a Royal Commission on Trade Unions. Three members of the commission, Frederic Harrison, Thomas Hughes and Thomas Anson, 2nd Earl of Lichfield, refused to sign the Majority Report as they considered it hostile to trade unions. They therefore published a Minority Report where he argued that trade unions should be given privileged legal status.

The Trade Union Congress campaigned to have the Minority Report accepted by the new Liberal government. Gladstone eventually agreed and the 1871 Trade Union Act was based largely on the Minority Report. This act secured the legal status of trade unions. As a result of this legislation no trade union could be regarded as criminal because "in restraint of trade"; trade union funds were protected. Although trade unions were pleased with this act, they were less happy with the Criminal Law Amendment Act passed the same day that made picketing illegal.

Working class males now formed the majority in most borough constituencies. However, employers were still able to use their influence in some constituencies because of the open system of voting. In parliamentary elections people still had to mount a platform and announce their choice of candidate to the officer who then recorded it in the poll book. Employers and local landlords therefore knew how people voted and could punish them if they did not support their preferred candidate.

In 1872 William Gladstone removed this intimidation when his government brought in the Ballot Act which introduced a secret system of voting. Paul Foot points out: "At once, the hooliganism, drunkenness and blatant bribery which had marred all previous elections vanished. employers' and landlords' influence was still brought to bear on elections, but politely, lawfully, beneath the surface."

Gladstone became very unpopular with the working-classes when his government passed the 1872 Licensing Act. This restricted the closing times in public houses to midnight in towns and 11 o'clock in country areas. Local authorities now had the power to control opening times or to become completely "dry" (banning all alcohol in the area). This led to near riots in some towns as people complained that the legislation interfered with their personal liberty.

Benjamin Disraeli made constant attacks on Gladstone and his government. In one speech in Manchester that lasted three and quarter hours he said that the government was losing its energy. He was suggesting that Gladstone, now aged 62, was too old for the job. "As I sat opposite the ministers reminded me of one of those marine landscapes not very uncommon on the coasts of South America. You behold a row of exhausted volcanoes. Not a flame flickers from a single pallid crest".

On 9th August 1873, Gladstone replaced Robert Lowe and became his own chancellor of the exchequer. Gladstone sought to regain the political initiative by a daring and dramatic financial plan: "abolition of Income Tax and Sugar Duties with partial compensation from Spirits and Death Duties". To balance the books he also needed some defence savings. However, the army and navy cabinet ministers refused.

Gladstone became very disillusioned with politics and considered resigning. Gladstone wrote in his diary on 18th January, 1874: "On this day I thought of dissolution". He told some of his senior ministers, John Bright, George Leveson-Gower and George Carr Glyn of his decision. "They all seemed to approve. My first thought of it was an escape from a difficulty. I soon saw on reflection that it was the best thing in itself."

As the prime minister,Benjamin Disraeli now had the opportunity to the develop the ideas that he had expressed when he was leader of the Young England group in the 1840s. Social reforms passed by the Disraeli government included: the Factory Act (1874) and the Climbing Boys Act (1875), Artisans Dwellings Act (1875), the Public Health Act (1875), the Pure Food and Drugs Act (1875). Disraeli also kept his promise to improve the legal position of trade unions. The Conspiracy and Protection of Property Act (1875) allowed peaceful picketing and the Employers and Workmen Act (1878) enabled workers to sue employers in the civil courts if they broke legally agreed contracts.

Early in his career Disraeli was not a strong enthusiast for building up the British Empire and had described colonies as "millstones around our neck" and had argued that the Canadians should "defend themselves" and that British troops should be withdrawn from Africa. However, once he became prime-minister he changed his view on the subject. He was especially interested in India, with its population of over 170 million. It was also an outlet for British goods and a source of valuable imports such as raw cotton, tea and wheat. It is possible that he saw the Empire as an "issue on which to damage his opponents by impugning their patriotism".

In one speech Disraeli attacked Liberals as being people who were not committed to the British Empire: "Gentlemen, there is another and second great object of the Tory party. If the first is to maintain the institutions of the country, the second is, in my opinion, to uphold the empire of England. If you look to the history of this country since the advent of Liberalism - forty years ago - you will find that there has been no effort so continuous, so subtle, supported by so much energy, and carried on with so much ability and acumen, as the attempts of Liberalism to effect the disintegration of the empire of England."

Disraeli got on very well with Queen Victoria. She approved of Disraeli's imperialist views and his desire to make Britain the most powerful nation in the world. In May, 1876 Victoria agreed to his suggestion that she should accept the title of Empress of India. The title was said to be un-English and the proposal of the measure also seemed to suggest an unhealthily close political relationship between Disraeli and the Queen. The idea was rejected by Gladstone and other leading figures in the Liberal Party.

In May 1876 it was reported that Turkish troops had murdered up to 7,000, Orthodox Christians in the Balkans. Gladstone was appalled by these events and on 6th September he published Bulgarian Horrors and the Question of the East (1876). He sent a copy to Benjamin Disraeli who described the pamphlet as "vindictive and ill-written... indeed in that respect of all the Bulgarian horrors perhaps the greatest."

The initial print run of 2,000 sold out in two days. Several reprints took place and eventually over 200,000 copies of the pamphlet were sold. On 9th September, Gladstone addressed an audience of 10,000 at Blackheath on the subject and became the leader of the "popular front of moral outrage". Gladstone stated that "never again shall the hand of violence be raised by you, never again shall the flood-gates of lust be open to you, never again shall the dire refinements of cruelty be devised by you for the sake of making mankind miserable."

William Gladstone's approach was in stark contrast to what has been called "Disraeli's sardonic cynicism". Robert Blake has argued that the conflict between Gladstone and Disraeli "injected a bitterness into British politics which had not been seen since the Corn Law debates". It has been claimed that "Gladstone developed a new form of evangelical mass politics" over this issue.

Benjamin Disraeli believed William Gladstone was using the massacre to further his political career. He told a friend: "Posterity will do justice to that unprincipled maniac Gladstone - extraordinary mixture of envy, vindictiveness, hypocrisy and superstition; and with one commanding characteristic - whether preaching, praying, speechifying, or scribbling - never a gentleman!"

Disraeli suffered from increasingly bad health and endured periods of gout, asthma, and bronchitis. "He perceived that his physical powers were not sufficient to continue to lead the Commons effectively". Disraeli volunteered to resign the premiership. Queen Victoria rejected the idea and in August 1876 she made him earl of Beaconsfield. Disraeli now left the House of Commons but continued as Prime Minister and now used the House of Lords to explain his government's policies.

Gladstone began to attack the foreign policy of the Conservative government. He attacked imperialism and warned of the dangers of a bloated empire with worldwide responsibilities which in the long run would become unsustainable. He pointed out that military spending had turned an inherited surplus of £6 million into a deficit of £8 million. As a result of these views, Prince George, Duke of Cambridge (the commander-in-chief) refused to shake Gladstone's hand when he met him. When his house was attacked by a Jingo mob on a Sunday evening, Gladstone wrote in his diary: "This is not very sabbatical".

In the 1880 General Election the Liberal Party won 352 seats with 54.7% of the vote. Benjamin Disraeli resigned and Queen Victoria invited Spencer Cavendish, Lord Hartington, the official leader of the party, to become her new prime minister. He replied that the Liberal majority appeared to the nation as being a "Gladstone-created one" and that Gladstone had already told other senior figures in the party he was unwilling to serve under anybody else.

Victoria explained to Hartington that "there was one great difficulty, which was that I could not give Mr. Gladstone my confidence." She told her private secretary, Sir Henry Frederick Ponsonby: "She will sooner abdicate than send for or have any communication with that half mad firebrand who would soon ruin everything and be a dictator. Others but herself may submit to his democratic rule but not the Queen."

Victoria now asked to see Granville Leveson-Gower, 2nd Earl Granville. He also refused to be prime minister, explaining that Gladstone had a "great amount of popularity at the present moment amongst the people". He also suggested that Gladstone, now aged 70, would probably retire by 1881. Victoria now agreed to appoint Gladstone as her prime minister. That night he recorded in his diary that the Queen received him "with the perfect courtesy from which she never deviates".

Benjamin Disraeli decided to retire from politics. Disraeli hoped to spend his retirement writing novels but soon after the publication of Endymion (1880) he became very ill with severe bronchitis. Queen Victoria wanted to visit Disraeli but he rejected the idea. He is said to have remarked: "No it is better not. She would only ask me to take a message to Prince Albert". Disraeli died aged 76 on 19th April, 1881.

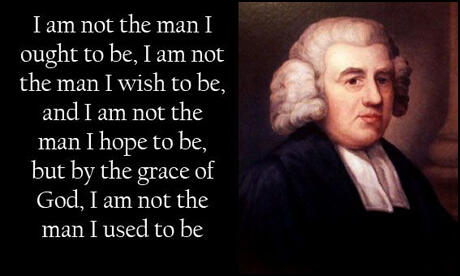

On this day in 1807 John Newton died. Newton was born on 24th July 1725 in Wapping. His father was a master mariner. His mother died of tuberculosis when John was only six. His father remarried after his mother's death, but John did not enjoy a good relationship with his stepmother.

In 1733 Newton was sent to a boarding-school at Stratford. At the age of eleven he went to sea with his father. A few years later he became a crew member of a slave-ship. He later recalled that he was based in Sierra Leone "for the purpose of purchasing and collecting slaves, to sell to the vessels that arrived from Europe."

Newton later explained: "The slaves, in general, are bought, and paid for. Sometimes, when goods are lent, or trusted on shore, the trader voluntarily leaves a free person, perhaps his own son, as a hostage, or pawn, for the payment; and, in case or default, the hostage is carried off, and sold; which, however hard upon him, being in consequence of a free stipulation, cannot be deemed unfair. There have been instances of unprincipled captains, who, at the close of what they supposed their last voyage, and when they had no intention of revisiting the coast, have detained, and carried away, free people with them; and left the next ship, that should come from the same port, to risk the consequences. But these actions, I hope, and believe, are not common."

Newton argued that it was important to have as many slaves as possible on board the slave-ship: "With our ships, the great object is, to be full. When the ship is there, it is thought desirable, she should take as many as possible. The cargo of a vessel of a hundred tons, or little more, is calculated to purchase from two hundred and twenty to two hundred and fifty slaves. Their lodging-rooms below the deck, which are three (for the men, the boys, and the women) besides a place for the sick, are sometimes more than five feet high, and sometimes less; and this height is divided towards the middle, for the slaves lie in two rows, one above the other, on each side of the ship, close to each other, like books upon a shelf. I have known them so close, that the shelf would not, easily, contain one more. Let it be observed, that the poor creatures, thus cramped for want of room, are likewise in irons, for the most part both hands and feet, and two together, which makes it difficult for them to turn or move, to attempt either to rise or to lie down, without hurting themselves, or each other."

John Newton admitted that conditions on board ship were appalling: "The heat and the smell of these rooms, when the weather will not admit of the slaves being brought upon deck, and of having their rooms cleaned every day, would be, almost, insupportable, to a person not accustomed to them. If the slaves and their rooms can be constantly aired, and they are not detained too long on board, perhaps there are not many die; but the contrary is often their lot. They are kept down, by the weather, to breathe a hot and corrupted air, sometimes for a week: this, added to the galling of their irons, and the despondency which seizes their spirits, when thus confined, soon becomes fatal."

On one occasion Newton kept a record of how many slaves died on a journey from Africa to South Carolina: "The ship, in which I was mate, left the coast with two hundred and eighteen slaves on board; and though we were not much affected by epidemical disorders, I find, by my journal of that voyage (now before me) that we buried sixty-two on our passage to South Carolina, exclusive of those which died before we left the coast, of which I have no account. I believe, upon an average between the more healthy, and the more sickly voyages, and including all contingencies, One fourth of the whole purchase may be allotted to the article of mortality. That is, if the English ships purchase sixty thousand slaves annually, upon the whole extent of the coast, the annual loss of lives cannot be much less than fifteen thousand."

Newton also took slaves to Antigua. He later recalled a conversation with a man who purchased slaves from Newton: "He said, that calculations had been made, with all possible exactness, to determine which was the preferable, that is, the most saving method of managing slaves". He went onto say that they needed to decided: "Whether, to appoint them moderate work, plenty of provision, and such treatment, as might enable them to protract their lives to old age? Or, by rigorously straining their strength to the utmost, with little relaxation, hard fare, and hard usage, to wear them out before they became useless, and unable to do service; and then, to buy new ones, to fill up their places?" Newton added: "He farther said, that these skillful calculators had determined in favor of the latter mode, as much the cheaper; and that he could mention several estates, in the island of Antigua, on which, it was seldom known, that a slave had lived above nine years."

Newton's biographer, Bruce Hindmarsh, points out: "His behaviour during this whole period involved ribald and blasphemous language; he also alludes vaguely to sexual misconduct. After six months trading he determined to stay on the Guinea coast of Africa to work in the onshore trade, hoping to make his fortune as a slave factor on one of the Plantanes islands off the coast of Sierra Leone. Instead during the next two years he suffered illness, starvation, exposure, and ridicule as his master, a man named Clow, used him brutally. Newton always marked this point as the nadir of his spiritual journey."

On 21st March, 1748, Newton was aboard The Greyhound when he encountered a severe north Atlantic storm. Newton resorted to saying his prayers and because he survived he developed a new faith in God. Newton began to read the Bible and other religious books. However, he continued to work on ships taking slaves from the Guinea coast and the West Indies (1748–9).

John Newton married Mary Catlett on 12th February 1750. He became master of slave-trading ships, The Duke of Argyle (1750–51) and The African (1752–54). Bruce Hindmarsh has argued "Newton has sometimes been accused of hypocrisy for holding strong religious convictions at the same time as being active in the slave trade, praying above deck while his human cargo was in abject misery below deck."

In 1754 Newton suffered a convulsive fit and was forced to leave the maritime trade. Later that year he attended religious meetings addressed by George Whitefield and John Wesley. In August 1755 Newton took up a civil service post as tide surveyor at Liverpool. He also became a leading evangelical laymen in the region. This included hosting large religious meetings in his own home.

Newton was considered a Methodist and was unsuccessful in several applications for orders in the Church of England. He sent the first draft of his autobiography to William Legge, 2nd Earl of Dartmouth. With his support Newton received deacon's orders, on 29th April 1764, from the Bishop of Lincoln. Newton became curate-in-charge of Olney in Buckinghamshire. Later that year Newton's Authentic Narrative appeared in print and it immediately established his place as one of the country's leading evangelicals.

Newton had become friends with the poet, William Cowper and in 1771 they began to collaborate formally on a project to publish a volume of their collected hymns. Olney Hymns was published in 1779. Newton's most famous contributions include Glorious Things of Thee are Spoken, How Sweet the Name of Jesus Sounds! and Amazing Grace. In his book, Life of Cowper (1835) Robert Southey claimed that Newton's influence had served to undermine Cowper's sanity.

In January 1780 Newton accepted the offer from John Thornton of the benefice of St Mary Woolchurch in Lombard Street. The living was worth just over £260 a year. He became close friends with William Wilberforce and became involved in his campaign against the slave-trade. In 1787 Newton published Thoughts upon the African Slave Trade (1787). He admitted that this was "a confession, which... comes too late....It will always be a subject of humiliating reflection to me, that I was once an active instrument in a business at which my heart now shudders."

John Newton explained why he had become involved in the campaign against the slave trade: "The nature and effects of that unhappy and disgraceful branch of commerce, which has long been maintained on the Coast of Africa, with the sole, and professed design of purchasing our fellow-creatures, in order to supply our West-India islands and the American colonies, when they were ours, with slaves; is now generally understood. So much light has been thrown upon the subject, by many able pens; and so many respectable persons have already engaged to use their utmost influence, for the suppression of a traffic, which contradicts the feelings of humanity; that it is hoped, this stain of our National character will soon be wiped out."

John Newton died on 21st December 1807 and was buried by the side of his wife in St Mary Woolchurch on 31st December; both bodies were reinterred at Olney in 1893.

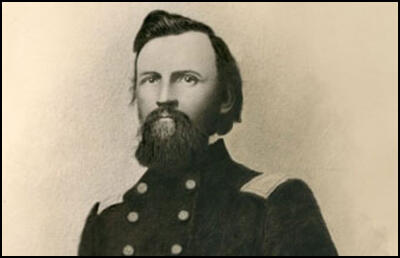

On this day in 1829 Hans Christian Heg was born in Norway. His family emigrated to America when he was eleven years old. Heg settled in Waterford, Wisconsin and in 1851 married Gunild Einong.

Heg was a Major in the 4th Wisconsin Militia and became the first Norwegian to be elected to state office when he became State Prison Commissioner of Wisconsin.

On the outbreak of the Civil War Heg joined the Union Army and was given the rank of Colonel and was heavily involved in recruiting the 15th Wisconsin, the Scandinavian Regiment.

Heg led the regiment during the successful raid on Union City, Tennessee. After an extensive campaign in Tennessee, Mississippi, and Alabama, Heg took part in the battle at Perryville (8th October, 1862). He was injured when his horse fell and was sent back to Wisconsin to recover.

Back on duty he led the capture of a Confederate artillery battery at Knob Gap, Tennessee (15th December, 1862). He then commanded the Scandinavian Regiment during the battle of Murfreesboro (Stones River). Despite suffering serious losses his brigade commander reported: "Colonels Alexander and Heg, in my opinion, proved themselves the bravest of the brave. Had such men as these been in command of some of our brigades, we should have been spared the shame of witnessing the rout of our troops and the disgraceful panic, encouraged, at least, by the example and advice of officers high in command."

In May, 1863, Heg was placed in command of the newly formed 3rd Brigade of the 1st Division, 20th Army Corps. On 29th August he led an early morning assault across the Tennessee River. The 3rd Brigade crossed over without a single casualty, therefore becoming the first Union troops south of the river.

Heg, about to be promoted to the rank of Brigadier General, led his men at Chickamauga in Georgia (19th September, 1863). Around 5 o'clock, just before the fighting finished, Heg was shot in the abdomen. Heg was taken to the Field Hospital at Crawfish Springs, but died the following day. Hans Christian Heg, the highest ranking officer in the Union Army in Wisconsin to be killed, is buried in the Norway Lutheran Church Cemetery in Racine County.

On this day in 1850 the Illustrated London News describes the plight of emigrants at Liverpool waiting to be taken to Boston. "Here are women with swollen eyes, who have just parted with near and dear ones, perhaps never to meet again, and mothers seeking to hush their wailing babes. In one place sits an aged woman listless and sad, scarcely conscious of the bustle and confusion around her. The voyage across the Atlantic is another dreary chapter in an existence made up of periods of strife with hard adversities."

At the beginning of the 19th century Liverpool was the main port used by those wanting to travel to the United States. As well as English emigrants, virtually all those from Ireland sailed from this port. So also did large numbers from Germany, Sweden and Norway. It is estimated that around a half of all Europe's emigrants went via Liverpool. In 1830 an estimated 15,000 emigrants went from Liverpool. This increased to over 50,000 in 1842.

By the middle of the 19th century an average of 200,000 emigrants a year were leaving from Liverpool. This was more than half of all emigrants to America. However, as the century progressed, German ports such as Bremen and Hamburg became more important, as they were geographically better placed to cater for the growing number of emigrants from central and eastern Europe.

On this day in 1865 Nina Boyle, the second daughter and fifth of the six children of Robert Boyle (1830–1869), was born in Bexley, Kent. Her father was the son of David Boyle. After his death she spent time in South Africa and worked as a nurse during the Boer War.

Boyle was a strong supporter of women's suffrage and helped establish the Women's Enfranchisement League of Johannesburg. After returning to Britain in 1911, she became active in the Women's Freedom League (WFL), which had been formed in 1907 after a split within the Women's Political and Social Union (WSPU) over the way Emmeline Pankhurst and Christabel Pankhurst were running the organisation. These women objected to the way that the Pankhursts were making decisions without consulting members. Other members of the WFL included: Charlotte Despard, Teresa Billington-Greig, Elizabeth How-Martyn, Dora Marsden, Helena Normanton, Anne Cobden Sanderson and Margaret Nevinson.

Like the WSPU, the WFL was a militant organisation that was willing the break the law. As a result, over 100 of their members were sent to prison after being arrested on demonstrations or refusing to pay taxes. However, members of the WFL was a completely non-violent organisation and opposed the WSPU campaign of vandalism against private and commercial property. The WFL were especially critical of the WSPU arson campaign.

Boyle, who wrote extensively for The Vote, became head of the WFL's political and militant department in 1912. According to her biographer, Marc Brodie: "She (Nina Boyle) was arrested on several occasions and imprisoned three times. Partly as a means of improving the treatment of women by the police - particularly given her own experiences - and also as part of the WFL's aim to make all employment areas open to women, Boyle attempted to gain approval for women to be employed as special constables."

After a meeting with Sir Edward Henry, the Chief Commissioner of Police, Nina Boyle and Margaret Damer Dawson founded the Women Police Volunteers. The following year Dawson became Commandant and Mary Allen became Sub-Commandant. The government had always opposed the idea of policewomen but with a large numbers of policemen joining the British Army, it was considered a good idea to have women volunteers to help run the service. Another reason that Dawson's proposal was accepted was that her members were willing to work without pay.

David Doughan argues that Margaret Damar Dawson was the right kind of leader for this new organisation: "Many of the first recruits, numbering approximately fifty, had experience of being imprisoned as militant suffragists, a point which was stressed by the rival Women's Police Patrols, set up by the National Union of Women Workers (later the National Council of Women). Margaret Damer Dawson's highly respectable non-suffragette background, together with the number of her aristocratic acquaintances, was thus an asset when dealing with figures of authority."

In February 1915 the Women Police Volunteers was renamed her organisation, the Women's Police Service (WPS). At first the WPS concentrated its work in the London area. Wearing a dark-blue uniform, the WPS were assigned responsibilities such as looking after the welfare of refugees. Later that year, Allen was sent to sort out problems in Grantham and Hull. Both towns had army camps and local people were complaining about drunken behaviour and a growth in prostitution. Boyle saw this as a "slur upon all women" and resigned from the WPV.

Eveline Haverfield was appointed as Commandant in Chief of the Women's Reserve Ambulance Corps and was instructed to organize the sending of the Scottish Women's Hospital Units to Serbia. The women left in August, 1916, and included Nina Boyle, Dr. Else Inglis, Elsie Bowerman, Lilian Lenton and Vera Holme.

After the passing of the Qualification of Women Act the first opportunity for women to vote was in the 1918 General Election. Boyle attempted to stand as a Women's Freedom League candidate in the Keighley by-election. However, her nomination was rejected because of a technical flaw.

In 1920 Boyle published a novel, Out of the Flying-Pan. Over the next few years she produced several novels with strong women characters. The most successful was What Became of Mr. Desmond? (1922). When her novel, The Rights of Mallaroche, appeared in 1927, the reviewer in the Times Literary Supplement remarked that he had to "mile at the feminism which Miss Boyle has kept hot from her suffragette days".

As Marc Brodie has pointed out: "During the 1920s and 1930s Boyle remained active in a broad range of women's organizations. She campaigned on behalf of the National Union of Women Teachers, the Women's Election Committee, the Open Door Council (which aimed to remove protective barriers that restricted women's employment opportunities), and also organizations concerned with the welfare of women and children in developing countries. She was particularly active in the Save the Children Fund (SCF)."

Boyle moved to the right in the 1920s and was a supporter of the British Empire Union (BEU) and the Conservative Party. During the Second World War she was a member of the Never Again Association, that campaigned for the expulsion from Britain of all persons born in Axis countries.

Nina Boyle, who never married, died in a nursing home at 99 Cromwell Road, London, on 4th March 1943, and five days later was cremated at Golders Green.

On this day in 1866 the Fetterman Massacre took place. In June 1866, Red Cloud, chief of the Oglala Sioux, began negotiating with the army based at Fort Laramie about the decision to allow emigrants to settle on the last of the great Sioux hunting grounds. When he was unable to reach agreement with the army negotiators he resorted to sending out war parties that attacked emigrants and army patrols. These hit and run tactics were difficult for the army to deal with and be the time they arrived on the scene of the attack the war parties had disappeared.

On 21st December, 1866, Captain W. J. Fetterman and an army column of 80 men, were involved in protecting a team taking wood to Fort Phil Kearny. Although under orders not to "engage or pursue Indians" Fetterman gave the orders to attack a group of Sioux warriors. The warriors ran away and drew the soldiers into a clearing surrounded by a much larger force. All the soldiers were killed in what became known as the Fetterman Massacre. Later that day the stripped and mutilated bodies of the soldiers were found by a patrol led by Captain Ten Eyck.

On this day in 1892 Cicely Fairfield (Rebecca West), the youngest of three children (all daughters) of Charles Fairfield (1843–1906) and his wife, Isabella Campbell Mackenzie (1853–1921), was born at 28 Burlington Road, Westbourne Park. Her father, an anti-socialist journalist, left the family when she was a child. Her feeling of desertion by her father persisted for the remainder of her life."

Cicely's mother was a talented pianist, having come from a musical family. Her brother, the violinist and composer Alick Mackenzie, was president of the Royal Academy of Music (1888–1924). After her husband left the family home, Isabella took her three children to her native Edinburgh.

Cicely attended George Watson's Ladies' College (1904–7). Although highly intelligent her headmistress did not encourage her to go to university. At first she wanted a career in the theatre and while studying at the Academy of Dramatic Art (1910–11), she took the name Rebecca West after the heroine of Ibsen's Rosmersholm). However, she had developed strong left-wing opinions and decided to become a journalist instead.

Three veterans of the women's suffrage campaign, Dora Marsden, Grace Jardine and Mary Gawthorpe, began publishing their a feminist journal, The Freewoman on 23rd November, 1911. In its first edition Rebecca West wrote an article in support for free-love: "Marriage had certain commercial advantages. By it the man secures the exclusive right to the woman's body and by it, the woman binds the man to support her during the rest of her life... a more disgraceful bargain was never struck."

This article created a storm. Mary Humphrey Ward, the leader of Anti-Suffrage League argued that the journal represented "the dark and dangerous side of the Women's Movement". According to Ray Strachey, the leader of the National Union of Suffrage Societies (NUWSS), Millicent Fawcett, read the first edition and "thought it so objectionable and mischievous that she tore it up into small pieces". Whereas Maude Royden described it as a "nauseous publication".

Other feminists were much more supportive, Ada Nield Chew, argued that the was "meat and drink to the sincere student who is out to learn the truth, however unpalatable that truth may be." Benjamin Tucker commented that it was "the most important publication in existence". Floyd Dell, who worked for the Chicago Evening Post argued that before the arrival of The Freewoman: "I had to lie about the feminist movement. I lied loyally and hopefully, but I could not have held out much longer. Your paper proves that feminism has a future as well as a past." Guy Aldred pointed out: "I think your paper deserves to succeed. I will use my influence in the anarchist movement to this end." Others showed their support for the venture by writing without payment for the journal. This included Teresa Billington-Greig, Rebecca West, H. G. Wells, Edward Carpenter, Havelock Ellis, Stella Browne, C. H. Norman, Huntley Carter, Lily Gair Wilkinson and Rose Witcup.

On 28th December 1911, Dora Marsden began a five-part series on morality. Dora argued that in the past women had been encouraged to restrain their senses and passion for life while "dutifully keeping alive and reproducing the species". She criticised the suffrage movement for encouraging the image of "female purity" and the "chaste ideal". Dora suggested that this had to be broken if women were to be free to lead an independent life. She made it clear that she was not demanding sexual promiscuity for "to anyone who has ever got any meaning out of sexual passion the aggravated emphasis which is bestowed upon physical sexual intercourse is more absurd than wicked."

Dora Marsden went on to attack traditional marriage: "Monogamy was always based upon the intellectual apathy and insensitiveness of married women, who fulfilled their own ideal at the expense of the spinster and the prostitute." According to Marsden monogamy's four cornerstones were "men's hypocrisy, the spinster's dumb resignation, the prostitute's unsightly degradation and the married woman's monopoly." Marsden then added "indissoluble monogamy is blunderingly stupid, and reacts immorally, producing deceit, sensuality, vice, promiscuity and an unfair monopoly." Friends assumed that Marsden was writing about her relationships with Grace Jardine and Mary Gawthorpe.

On 21st March 1912 Stella Browne wrote about her views on free-love in The Freewoman: "The sexual experience is the right of every human being not hopelessly afflicted in mind or body and should be entirely a matter of free choice and personal preference untainted by bargain or compulsion." According to her biographer, Lesley A. Hall: "Browne emphasized the need for women to speak about their own experiences. In both principle and practice Stella was a convinced believer in free love, known to have had various lovers, certainly some male, and possibly some female, though these cannot be reliably identified."

The articles on sexuality created a great deal of controversy. However, they were very popular with the readers of the journal. In February 1912, Ethel Bradshaw, secretary of the Bristol branch of the Fabian Women's Group, suggested that readers formed Freewoman Discussion Circles. Soon afterwards they had their first meeting in London and other branches were set up in other towns and cities.

Some of the talks that took place in the Freewoman Discussion Circles included Edith Ellis (Some Problems of Eugenics), Rona Robinson (Abolition of Domestic Drudgery), C. H. Norman (The New Prostitution), Huntley Carter (The Dances of the Stars) and Guy Aldred (Sex Oppression and the Way Out). Other active members included Rebecca West, Grace Jardine, Stella Browne, Harry J. Birnstingl, Charlotte Payne-Townshend Shaw, Havelock Ellis, Lily Gair Wilkinson, Françoise Lafitte-Cyon and Rose Witcup.

Rebecca West became very active in the socialist movement and joined the Fabian Society and met George Bernard Shaw at one of its summer schools. In 1912 she became a staff member of The Clarion. She soon developed a reputation as a perceptive reviewer. When she reviewed the novel, Marriage, she described the author, H. G. Wells, "the old maid among novelists". Wells responded by inviting West to his home. Soon afterwards they became lovers and a son, Anthony Panther West, was born on 4th August 1914.

Her biographer, Bonnie Kime Scott, has argued: "West's affair brought her a domesticity which she disliked, and rustication to various places discreetly accessible to Wells, already notorious for extramarital affairs. She happily settled in her own London flat in 1919." Her first novel, Return of the Soldier (1918), was about a soldier from the First World War suffering from shell-shock. This was followed by the novelsThe Judge (1922), The Strange Necessity (1928) and Harriet Hume (1929). She also wrote a study of the author D. H. Lawrence (1930). She also wrote articles for the Daily News, The Star, New Statesman and New Republic.

Rebecca West married Henry Andrews (1894–1968) on 1st November 1930. West continued to take a keen interest in politics and was a supporter of the Popular Front government in Spain during the Spanish Civil War. She joined with Emma Goldman, Sybil Thorndyke, Fenner Brockway and C. E. M. Joad to establish the Committee to Aid Homeless Spanish Women and Children.

Bonnie Kime Scott has pointed out: "Rebecca West has gradually gained recognition as a perceptive and independent interpreter of literature... West's accounts of literature and culture are typically grounded in philosophical paradigms and cultural diagnoses that invite critical study today. She found pervasive examples of Manichaeism, and joined anthropologists of her era in detecting examples of Western degeneracy."

After the Second World War West became more conservative in her political views and wrote for the Daily Telegraph and the New Yorker. Some of her work was extremely anti-communist and some critics, including Arthur Schlesinger and J. B. Priestley, accused of her being in sympathy with McCarthyism - a charge she denied.

Other books published by Rebecca West included The Meaning of Treason (1949), The Fountain Overflows (1957), The Court and the Castle (1958), The Birds Fall Down (1966), McLuhan and the Future of Literature (1969) and 1900 (1982).

Rebecca West died on 15th March 1983 at 48 Kingston House North, South Kensington. She was buried at Brookwood Cemetery, near Woking.

On this day in 1919 Emma Goldman is deported to Russia. After the death of Johann Most, Emma Goldman became the leader of the anarchist movement in the United States. Along with Alexander Berkman she published the radical journal, Mother Earth and produced books such as Anarchism and Other Essays (1910) and and The Social Significance of the Modern Drama (1914). They also helped organize the Ferrer School in New York City and industrial disputes such as the Lawrence Textile Strike.

In 1919 Woodrow Wilson appointed A. Mitchell Palmer as his attorney general. Soon after taking office, a government list of 62 people believed to hold "dangerous, destructive and anarchistic sentiments" was leaked to the press. It was also revealed that these people had been under government surveillance for many years. Worried by the revolution that had taken place in Russia, Palmer became convinced that Communist agents were planning to overthrow the American government. Palmer recruited John Edgar Hoover as his special assistant and together they used the Espionage Act (1917) and the Sedition Act (1918) to launch a campaign against radicals and left-wing organizations.

A. Mitchell Palmer claimed that Communist agents from Russia were planning to overthrow the American government. On 7th November, 1919, the second anniversary of the Russian Revolution, over 10,000 suspected communists and anarchists were arrested. Palmer and Hoover found no evidence of a proposed revolution but large number of these suspects were held without trial for a long time. The vast majority were eventually released but Emma Goldman, Alexander Berkman, Mollie Steimer, and 245 other people, were deported to Russia.

As Agnes Smedley pointed out: "Much that we read of Russia is imagination and desire only. And no person is safe from intrigues and the danger of prison. The prisons are jammed with anarchists and syndicalists who fought in the revolution. Emma Goldman and Berkman are out only because of their international reputations. And they are under house arrest; they expect to go to prison any day, and may be there now for all I know. Any Communist who excuses such things is a scoundrel and a blaggard. Yet they do excuse it - and defend it. If I'm not expelled or locked up or something, I'll raise a small-sized hell. Everybody calls everybody a spy, secretly, in Russia, and everybody is under surveillance. You never feel safe."

Goldman and Berkman, who had already been appalled by the way that Lenin and Leon Trotsky had dealt with the Kronstadt Uprising decided to leave Russia as soon as possible. Berkman wrote: "Grey are the passing days. One by one the embers of hope have died out. Terror and despotism have crushed the life born in October. The slogans of the Revolution are forsworn, its ideals stifled in the blood of the people. The breath of yesterday is dooming millions to death; the shadow of today hangs like a black pall over the country. Dictatorship is trampling the masses under foot. The Revolution is dead; its spirit cries in the wilderness.... I have decided to leave Russia." After a brief stay in Stockholm, Berkman lived in Berlin, where he published several pamphlets and books on the Bolshevik government, including The Bolshevik Myth (1925).