Thomas Attwood

Thomas Attwood, the son of Matthias and Ann Attwood, was born at Hawne House, Halesowen on 6th October, 1783. Matthias Attwood was a successful businessman who owned extensive coal and iron interests in Halesowen and a bank in Birmingham. After being educated at Wolverhampton Grammar School, Thomas Attwood began work at his father's bank.

Attwood first became involved in politics when he joined the campaign against the East India Company. Attwood believed that the actions of the company was severely restricting foreign trade. As many local businesses depended on the export trade, the East India Company was blamed for the growing unemployment in Birmingham.

In 1812 the government appointed a Select Committee to of the House of Commons to investigate the activities of the East India Company. Attwood led the Birmingham delegation which gave evidence to the Committee. Attwood was a very impressive witness and his evidence was partly responsible for convincing the House of Commons to restrict the company's monopoly of foreign trade.

Thomas Attwood now began to take an interest in economic matters and in 1815 he put forward a policy that he believed would reduce unemployment. Attwood argued that Britain should have a paper currency which was not tied to gold. His second theory was that the government should counter economic depressions by increasing the money supply.

Attwood's economic theories were popular in Birmingham but he failed to convince the government. Although he managed to persuade 40,000 people to sign a petition advocating currency reform, the Duke of Wellington and his government refused to consider Attwood's proposal. Attwood gradually developed the view that the House of Commons needed more people with business experience and knowledge of economics. He therefore joined the demand for large manufacturing towns like Birmingham to be represented in Parliament.

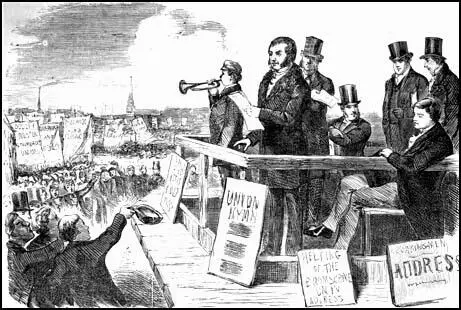

On 25th January, 1830, about 10,000 people attended the first meeting of the Birmingham Political Union. People listened for six hours to speeches made by Attwood and other leaders of the organisation. Another meeting in May at the Beardsworth Repository in Birmingham was attended by over 80,000 people. Other manufacturing towns in Britain began to follow Birmingham's example and formed Political Unions.

For the next two years Attwood was one of the main leaders in the campaign for parliamentary reform. When the Reform Act was eventually passed in 1832, Attwood was installed as a freeman of the City of London in recognition of the important role he had played in the fight for the vote. In the general election held in the autumn of 1832 Attwood and another leading member of the Political Union, Joshua Scholefield, were elected unopposed as Birmingham's first two MPs.

Attwood worked hard to convince the House of Commons of the wisdom of his economic ideas. However, he was unsuccessful at persuading his fellow MPs and he eventually came to the conclusion that a further reform of Parliament was needed. In May, 1837, the Birmingham Political Union was revived. In June a new list of demands were drawn up, including: currency reform, household suffrage, triennial parliaments, payment of MPs, and the abolition of the property qualification.

In January 1838 Thomas Attwood and the Birmingham Political Union began to work with the London Working Men's Association in the fight for the vote. However, Attwood objected to the aggressive speeches made by Feargus O'Connor and was much more closely aligned with William Lovett, Henry Hetherington, John Cleave and the other Moral Force Chartists.

In June 1839, Attwood presented the first National Petition to the House of Commons. Although it had been signed by over 1,280,000 people, the Commons rejected the petition by 235 votes to 46. Frustrated by the unwillingness of Parliament to respond to public pressure, and aware that many of the Chartist leaders had doubts about currency reform, Attwood decided to resign from Parliament. Attwood took no further part in politics. In later life Attwood suffered from creeping paralysis.

Thomas Attwood died in Malvern on 9th March 1859.

Primary Sources

(1) Thomas Attwood, speech at a meeting of the Birmingham Political Union (June, 1837)

We have against us, the whole of the aristocracy, nine-tenths of the gentry, the great body of the clergy, and all the pensioners, sinecurists, and bloodsuckers that feed on the vitals of the people.

(2) R. G. Gammage, History of the Chartist Movement (1894)

Mr. Attwood delivered a speech. He professed himself a peaceful man, and declared that he would never sanction the commission of violence for gaining the people's object, but as he warmed to the subject, he talked about the legislature being unable to resist the demand for two millions of men, which, which, if not speedily complied with, would result in the two millions being increased to five. If petitioning was found to fail in making the necessary impression, the honourable gentleman suggested a national strike for one week, during which time not a hammer was to be wielded, nor an anvil sounded, not a shuttle moved, throughout the country, and he told his hearers that although he would be opposed to the employment of any violence, if the people were attacked the consequences must fall on the heads of the aggressors. He told the meeting too, that if the government dared to arrest him in the execution of his peaceful purpose, a hundred thousand men would march to demand his release.

(3) Feargus O'Connor, speech (3rd August, 1839)

This is a wild and visionary scheme of Attwood's, to starve the people into paper money. However, I have no objection to try the experiment, providing the rich who suggested it, will deposit in the hands of the committees, either money or food to stand the strike.