Evacuation in the Second World War

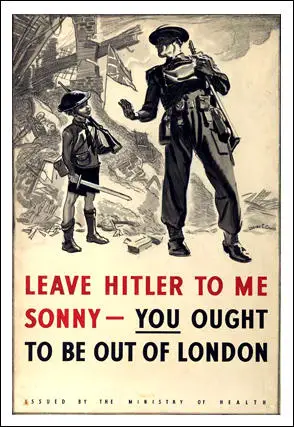

The government made plans for the evacuation of all children from Britain's large cities. Sir John Anderson, who was placed in charge of the scheme, decided to divide the country into three areas: evacuation (people living in urban districts where heavy bombing raids could be expected); neutral (areas that would neither send nor take evacuees) and reception (rural areas where evacuees would be sent). It is estimated that between June and August 1939 some 3,750,000 moved from areas thought vulnerable to those considered safe. (1)

Herbrand Sackville, 9th Earl De La Warr, President of the Board of Education, attempted to reassure mothers anxious about their children who had been evacuated from danger zones. "I do wish that some of you parents of evacuated children could see the effects of your children of only a few days in the country. If you are feeling anxious about them, I think it would reassure you. Our task must be to save your children as far as possible from the sufferings and beastliness of modern war. So, however much you may miss them, don't take your children back just because nothing has happened during the first few days of war." (2)

In July, 1939, the government published a leaflet, Evacuation: Why and How?: "If we were involved in war, our big cities might be subjected to determined attacks from the air - at any rate in the early stages - and although our defences are strong and are rapidly growing stronger, some bombers would undoubtedly get through. We must see to it then that the enemy does not secure his chief objects - the creation of anything like panic, or the crippling dislocation of our civil life. One of the first measures we can take to prevent this is the removal of the children from the more dangerous areas. The scheme is entirely a voluntary one, but clearly the children will be much safer and happier away from the big cities where the dangers will be greatest." (3)

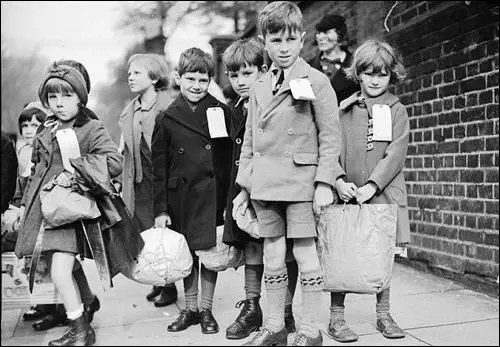

After the outbreak of the war the number of evacuees increased rapidly. It is believed that in September 1939 alone around a quarter of the population moved. According to Angus Calder: "It was, on the surface, a triumph of calm and order. The parties, clutching gas masks and emergency rations, shepherded by their teachers, were guided and controlled by an elaborate system of banners, armlets and labels." Official records claim that 47 per cent of primary schoolchildren, and about one third of the mothers went to the designated areas. This included 827,000 schoolchildren, 524,000 mothers and children under school age going together, 13,000 expectant mothers, 7,000 blind, crippled or otherwise handicapped people; and 103,000 teachers and helpers. (4)

Jim Woods lived in Lambeth and at the age of six was evacuated with his sister. "I remember going to the station and there were literally hundreds of children lined up waiting to go. Everyone had a cardboard box with their gas masks in and a label tied to their coats to identify them if they got lost. We ended up in South Wales. The first night we slept on the floor of the church hall. The next day my sister and I were allocated to a Mr. and Mrs. Reece. At first it was quite frightening being separated from your mother and not understanding what was going on. However, after a few days we settled down and quite enjoyed being in Wales. After living in London we were now surrounded by countryside. The village was lived in was very small. There were mines close up by and we had great fun exploring the slag heaps. My sister and I got on very well with Mr. and Mrs. Reece. There were upsets sometimes. On one occasion we decided to go home to London. We followed the railway track. We thought it would take us back to London but after following it for about a mile we discovered it was a railway line used by the local mines." (5)

The billetor received received 10s. 6d. from the government for taking a child. Another 8s. 6d. per head was paid if the billetor took more than one. For mothers and infants, the billetor provided lodging only at a cost of 5s. per adult and 3s. per child. The people who took the children into their homes complained about the state of their health. Research suggests that around half of the evacuated children had fleas or headlice. Others suffered from impetigo and scabies. Muriel Green lived in the village of Snettisham in Norfolk: "The village people objected to the evacuees chiefly because of the dirtiness of their habits and clothes." (6)

Billetors were sometimes appalled by the behaviour of the evacuees. It is estimated that about 5 per cent of the evacuees lacked proper toilet training. One billetor reported about how when one six year old boy went to the toilet in the front room his mother shouted: "You dirty thing, messing up the lady's carpet. Go and do it in the corner." (84) Another report suggested: "The state of the children was such that the school had to be fumigated after the reception. Except for a small number the children were filthy, and in this district we have never seen so many verminous children lacking any knowledge of clean and hygienic habits." (7)

Oliver Lyttelton, a Member of Parliament, allowed ten children from London to live in his large country house. He later complained: "I got a shock. I had little dreamt that English children could be so completely ignorant of the simplest rules of hygiene, and that they would regard the floors and carpets as suitable places upon which to relieve themselves." (9) However, according to Richard Titmuss, evacuation meant that the "poor housed the poor... and the wealthier classes evaded their responsibilities throughout the war." (10)

The Dorking branch of the National Federation of Women's Institutes, produced a report on the children evacuated to their area. "It appeared they were unbathed for months... Condition of their boots and shoes - there was hardly a child with a whole pair and most of the children were walking on the ground - no soles, and just uppers hanging together... Many of the mothers and children were bed-wetters and were not in the habit of doing anything else... The appalling apathy of the mothers was terrible to see." (11)

Children evacuated to Oxford and Cambridge were asked to write essays explaining what they liked and disliked about their new homes. A thirteen year old girl wrote: "There isn't much that I really like in Cambridge. I like the meadows and parks in the summer but it is too cold in the winter to go there. I miss my home in Tottenham and I would rather be there than where I am. I cannot find much to do down here. I miss my sister and my friends. I haven't any of my friends living in Newnham (Cambridge) where I live and I never know where to go on Saturday and Sunday as I have no one to go with. At home I can stop in on Saturday if it is cold, but I have to take my brother out because the lady in this house goes to work and sometimes it is too cold to go anywhere. I miss my cup of tea which I always have at home after dinner. I miss my mother's cooking because the lady does not cook very well." (12)

About two million people adults privately evacuated themselves - to Wales, Devon, Scotland and other quiet areas. Constantine Fitzgibbon reported that his mother was inundated with requests to take in wealthy strangers from London: "A constant stream of private cars and London taxis" arrived in September, 1939, "filled with men and women of all ages and in various stages of hunger, exhaustion and fear, offering absurd sums for accommodation in her already overcrowded house, and even for food. This horde of satin-clad, pin-striped refugees poured through for two or three days, eating everything that was for sale, downing all the spirits in the pubs, and then vanished." (13)

Kate Eggleston, admitted that sometimes the evacuated children were badly treated: "I was at primary school when war broke out, in Nottingham. As a small child I can remember the evacuees coming. We were horrible to them. It's one of my most shameful memories, how nasty we were. We didn't want them to come, and we all ranged up on them in the playground. We were all in a big circle and the poor evacuees were herded together in the middle, and we were glaring at them and saying, 'You made us squash up in our classrooms, you've done this, you're done that.' I can remember them now, looking frightened to death. They were poor little East-Enders, they weren't tough at all, they were poor little thin, puny things. They used to be very quiet, and they only used to talk to themselves. We weren't friendly with them at all, we were very much apart, we just ignored them. It was prejudice from the teachers from the word go. When the evacuees arrived, they were pushed round from classroom to classroom in a big bunch according to their ages, in no welcoming way. All the existing children had to sit three to a bench instead of two, so we all moved up, and the evacuees sat down by the windows, which must have been the coldest and the draughtiest place in the classroom. I remember that we were put into sets, and that the 'duffers' were the ones who sat by the window, so all the evacuees were in the duffers' set." (14)

Some children were very happy with their situation: "I was 5½ years old when war was declared; I lived in Coventry with my parents and two teenage sisters... I was at school at St Joseph's Convent, which was evacuated to Stoneleigh Abbey, a fantastic country manor house with large grounds, huge trees and flowering bushes. I found it very different from life in a busy city. We slept on camp beds in the ballroom and were given navy blue blankets. I was fortunate enough to have my bed by the window and was allowed to put my teddies on the windowsill... I was delighted to find that the teacher who was sleeping with us was our music teacher... She was very kind and would comfort all the children who were homesick and explained why we had to be there. Fortunately, most of the children adapted to the situation fairly quickly." (15)

When the expected bombing of cities did not take place in 1939, parents began to doubt whether they had made the right decision in evacuating their children to safe areas. As Muriel Green pointed out: "Many evacuees returned to London because on the night of 3rd September, and the morning of the 6th there was an air-raid warning. They said they thought they had been sent to safety areas, but they decided they were no safer on the East Coast than in London especially as they have air-raid shelters in their gardens and in the parks. There are none here." (16)

By January 1940, an estimated one million evacuees had returned home. A survey carried out suggested that the lack of bombing was the reason why four out of five decided to leave. Other reasons given were homesickness among the children, dissatisfaction with the foster home and the loneliness of the parents. "Once the retreat from evacuation started, it was sure to become a rout. Parents from the same street or block of flats, travelling down to see their children at the week-ends and travelling back again together, would soon form a common resolution to bring their children back again." (17)

Primary Sources

(1) Government leaflet, Evacuation: Why and How? (July, 1939)

There are still a number of people who ask "What is the need for all this business about evacuation? Surely if war comes it would be better for families to stick together and not go breaking up their homes?"

It is quite easy to understand this feeling, because it is difficult for us in this country to realise what war in these days might mean. If we were involved in war, our big cities might be subjected to determined attacks from the air - at any rate in the early stages - and although our defences are strong and are rapidly growing stronger, some bombers would undoubtedly get through.

We must see to it then that the enemy does not secure his chief objects - the creation of anything like panic, or the crippling dislocation of our civil life.

One of the first measures we can take to prevent this is the removal of the children from the more dangerous areas. The Government have accordingly made plans for the removal from what are called " evacuable" areas to safer places called " reception " areas, of school children, children below school age if accompanied by their mothers or other responsible persons, and expectant mothers and blind persons.

The scheme is entirely a voluntary one, but clearly the children will be much safer and happier away from the big cities where the dangers will be greatest.

There is room in the safer areas for these children; householders have volunteered to provide it. They have offered homes where the children will be made welcome. The children will have their schoolteachers and other helpers with them and their schooling will be continued.

If you have children of school age, you have probably already heard from the school or the local education authority the necessary details of what you would have to do to get your child or children taken away. Do not hesitate to register your children under this scheme, particularly if you are living In a crowded area. Of course it means heartache to be separated from your children, but you can be quite sure that they will be well looked after. That will relieve you of one anxiety at any rate. You cannot wish, if it is possible to evacuate them, to let your children experience the dangers and fears of air attack in crowded cities.

Children below school age must be accompanied by their mothers or some other responsible person. Mothers who wish to go away with such children should register with the Local Authority. Do not delay In making enquiries about this.

A number of mothers in certain areas have shown reluctance to register. Naturally, they are anxious to stay by their men folk. Possibly they are thinking that they might as well wait and see; that it may not be so bad after all. Think this over carefully and think of your child or children in good time. Once air attacks have begun it might be very difficult to arrange to get away.

(2) Herbrand Sackville, 9th Earl De La Warr, President of the Board of Education, radio broadcast (14th September, 1939)

I do wish that some of you parents of evacuated children could see the effects of your children of only a few days in the country. If you are feeling anxious about them, I think it would reassure you. Our task must be to save your children as far as possible from the sufferings and beastliness of modern war. So, however much you may miss them, don't take your children back just because nothing has happened during the first few days of war.

The time may come when air raids are a grim reality. The Government felt it to be sufficiently important, to save the nation's childhood, to put the whole transport system at its disposal for nearly four days. But it would hardly be possible to do the same again.

(3) National Federation of Women's Institutes, Town Children Through Country Eyes (1940)

The state of the children was such that the school had to be fumigated after the reception. Except for a small number the children were filthy, and in this district we have never seen so many verminous children lacking any knowledge of clean and hygienic habits.

It appeared they were unbathed for months... Condition of their boots and shoes - there was hardly a child with a whole pair and most of the children were walking on the ground - no soles, and just uppers hanging together... Many of the mothers and children were bed-wetters and were not in the habit of doing anything else... The appalling apathy of the mothers was terrible to see.

(4) Children evacuated to Oxford and Cambridge were asked to write essays explaining what they liked and disliked about their new homes. This is an extract from one of these essays written by a thirteen year old girl.

There isn't much that I really like in Cambridge. I like the meadows and parks in the summer but it is too cold in the winter to go there. I miss my home in Tottenham and I would rather be there than where I am. I cannot find much to do down here. I miss my sister and my friends. I haven't any of my friends living in Newnham (Cambridge) where I live and I never know where to go on Saturday and Sunday as I have no one to go with. At home I can stop in on Saturday if it is cold, but I have to take my brother out because the lady in this house goes to work and sometimes it is too cold to go anywhere. I miss my cup of tea which I always have at home after dinner. I miss my mother's cooking because the lady does not cook very well.

(5) A seventeen year old girl from London recorded her thoughts on evacuation for the Mass-Observation organization.

I was an evacuee for six weeks. The main problem between evacuees and hosts seems to me to be the difficulty of adapting one to the other. A few of the hosts treated their evacuees, mainly girls, as guests, or as they would their own children. But the majority treated the girls as unpaid maids.

A good deal of publicity has been given to the hosts burdened with dirty, verminous evacuees, but none or very little to cases where well brought up, middle class girls and boys have been billeted in poor, dirty homes, where they have little to eat and none of the facilities they are used to. At least half of the 250 girls evacuated with the school are billeted in tiny, dirty houses where they have to do any housework that is done. Being billeted in such houses has a very bad effect on the younger girls of an impressionable age, and they grow slack in their care of their personal cleanliness and manners.

There are a good many clean middle class homes in the area but the owners of these homes have seen to it that they did not have to take in evacuees.

The Government allowance for evacuees is another problem. A great many hosts find it impossible to manage on the Government allowance and they grumble incessantly to their evacuees and demand a supplementary allowance from parents. When the parents explain that this has been forbidden the hosts become extremely disagreeable, nag the evacuees, give them poor food and their meals separate from the rest of the family. I think a great many of the problems of evacuation would be solved if evacuees were found billets roughly corresponding in class to their own homes.

(6) Kate Eggleston was a schoolchild in Nottingham during the war. Her recollections of evacuees appeared in the book, Don't You Know There's a War On? by Jonathan Croall (1989)

I was at primary school when war broke out, in Nottingham. As a small child I can remember the evacuees coming. We were horrible to them. It's one of my most shameful memories, how nasty we were. We didn't want them to come, and we all ranged up on them in the playground. We were all in a big circle and the poor evacuees were herded together in the middle, and we were glaring at them and saying, "You made us squash up in our classrooms, you've done this, you're done that." I can remember them now, looking frightened to death. They were poor little East-Enders, they weren't tough at all, they were poor little thin, puny things. They used to be very quiet, and they only used to talk to themselves. We weren't friendly with them at all, we were very much apart, we just ignored them.

It was prejudice from the teachers from the word go. When the evacuees arrived, they were pushed round from classroom to classroom in a big bunch according to their ages, in no welcoming way. All the existing children had to sit three to a bench instead of two, so we all moved up, and the evacuees sat down by the windows, which must have been the coldest and the draughtiest place in the classroom. I remember that we were put into sets, and that the 'duffers' were the ones who sat by the window, so all the evacuees were in the duffers' set.

(7) Evelyn Rose was a fourteen year old girl living in London when the war began in 1939. She was interviewed about her experiences for the book, Voices from the Past: The Blitz (1987).

I was fourteen when war was declared. In the interests of safety, it was decided that my sister and I should be evacuated. We went to Chorley Wood which was only 30 miles from London but it was considered to be a safe area. We were billeted with a family in a large house where there were servants. It was not something that we were used to. We were terribly homesick and unhappy and after a few months we went home.

Back at home I got a job working in an office producing service uniforms. As the factory had a big basement it was turned into a shelter for the factory employees. That's how we spent our evenings. All huddled together listening to the sirens and bombs.

We got through nearly a year of that and then we had a terrible tragedy. It was September 19, 1940. The war had been on a year. My mother had a cleaning lady and she left my sister with her while she went out to do some shopping. Where we lived had a direct hit. The cleaning lady escaped but my sister was killed. She was eight years and three days. My parents never got over it. Virtually everything we had was destroyed.

(8) Margaret Cole, Evacuation Survey (1940)

One priest felt it necessary to call upon the parents of the evacuees to insist upon their return home, alleging that any physical danger they might incur thereby was trifling when compared with the spiritual dangers they ran by remaining.

(9) Bernard Kops, a thirteen year old boy from Stepney in London was billeted in a village in Buckinghamshire. He wrote about his experiences in his autobiography, The World is a Wedding (1963)

Everything was so clean in the room. We were even given flannels and toothbrushes. We'd never cleaned our teeth up till then. And hot water came from the tap. And there was a lavatory upstairs. And carpets. And something called an eiderdown. And clean sheets. This was all very odd. And rather scaring.

(10) The National Federation of Women's Institutes carried out a survey of their members on their impressions of evacuation. The report, Town Children Through Country Eyes , was published in 1940. Here is a collection of things reported in the survey.

Except for a small number the children were filthy, and in this district we have never seen so many children lacking any knowledge of clean and hygienic habits. Furthermore, it appeared they were unbathed for months. One child was suffering from scabies and the majority had it in their hair and the others had dirty septic sores all over their bodies.

Many of the mothers and children were bed-wetters and were not in the habit of doing anything else. The appalling apathy of the mothers were terrible to see.

Their clothing was in a deplorable condition, some of the children being literally sewn into their ragged little garments. There was hardly a child with a whole pair (of shoes) and most of the children were walking on the ground - no soles, and just uppers hanging together." "The state of the children was such that the school had to be fumigated after the reception.

(11) Jim Woods was only five years old when the Second World War started. At the time his family lived in Lambeth.

I was eventually evacuated. I remember going to the station and there were literally hundreds of children lined up waiting to go. Everyone had a cardboard box with their gas masks in and a label tied to their coats to identify them if they got lost. We ended up in South Wales.

The first night we slept on the floor of the church hall. The next day my sister and I were allocated to a Mr. and Mrs. Reece. At first it was quite frightening being separated from your mother and not understanding what was going on. However, after a few days we settled down and quite enjoyed being in Wales. After living in London we were now surrounded by countryside. The village was lived in was very small. There were mines close up by and we had great fun exploring the slag heaps.

My sister and I got on very well with Mr. and Mrs. Reece. There were upsets sometimes. On one occasion we decided to go home to London. We followed the railway track. We thought it would take us back to London but after following it for about a mile we discovered it was a railway line used by the local mines.

We were in Wales for about two and a half years. After we went home Mr. Reece came to London and asked my mother if he could adopt us. I did not find out about this until I visited them after the war.

(12) Muriel Green, lived in the village of Snettisham in Norfolk, diary entry for the Mass Observation Archive (29th November, 1939)

Many evacuees returned to London because on the night of 3rd September, and the morning of the 6th there was an air-raid warning. They said they thought they had been sent to safety areas, but they decided they were no safer on the East Coast than in London especially as they have air-raid shelters in their gardens and in the parks. There are none here.

The village people objected to the evacuees chiefly because of the dirtiness of their habits and clothes. Also because of their reputed drinking and bad language. It's exceptional to hear women swear in the village or for them to enter a public house. The villagers used to watch them come out of the pubs with horror.

(13) Cynthia Gillett went to school in London during the Second World War. She wrote about her war experiences in Jonathan Croall's book, Don't You Know There's a War On? (1989)

We were evacuated twice during the war. The first time was to Edworth, a village in Bedfordshire, where we stayed for eight months. We were billeted in a manor house on a dairy farm. The parlourmaid, who was the one designated to actually look after us, used to beat you for reading in the morning. I can remember getting really severely beaten for reading Anne of Green Gables. She didn't approve of working-class people reading, and anyway morning was for work, not reading. She was a very sadistic woman. I had this younger sister, a funny little girl. I had to look after her all the time, I was always hemmed in. My mother used to say, 'Promise me you'll never leave her.' The parlour-maid didn't want to look after us, so she used to get at me through my sister if I didn't do what she wanted. She used to hold her head under the water, that sort of thing. So one day we ran away; there was a nice lady on the evacuation panel, and I can remember trying to find her in the village. The woman at the manor sent her son after us, so after that he had to follow us on the bus to make sure we went to school.

(14) Leonard England, Mass Observation report on an air-raid on Southampton (4th December, 1940)

Throughout Monday there was apparently a large unofficial evacuation. Two people spontaneously compared the lines of people leaving the town with bedding and prams full of goods to the pictures they had seen of refugees in Holland and Poland. Some official evacuation took place on the Monday, but at the Avenue Hall rest centre a group of fifty waited all the afternoon for a bus to take them out; the warning went when there were still no buses, and all of them went out to shelters without waiting any longer.

On Monday evening from about 4.30 onwards a stream of people were leaving the town for the night. When Mr. Andrews left the train at the docks, he was impressed by the seeming deadness of the town; there were no cars, and hardly any people except those that had left the train with him. But farther out people were moving. The buses were full, men and women were walking with their baggage. Some were going to relations in outlying parts, some to shelters, preceded by their wives who had reserved them places, and some to sleep in the open. 'Anything so as not to spend another night in there.' Many were trying to hitch hike, calling out to every car that passed; very few stopped. This caused considerable annoyance, especially as many coaches completely empty went by.

Trains leaving were full of women and children; many had little baggage, as if they were coming back next day. The next day many returned after the night, but more were intent on getting out. In some neighbourhoods whole streets had evacuated, most people leaving a note on their doors giving their new address; one such notice read 'Home all day, away all night'. Men as well as women were leaving; one man was going to Northampton to his son's, regretfully, after 26 years in Southampton.

All day people were leaving the town with suitcases and baggage. All of these seemed to set out with a set purpose and aim but all the aims were different. Here and there, for instance, there were streams of people all with baggage. Following these streams, Mr. Andrews saw them split up, some going to bus stops, others to trains. Both trains and buses were leaving half empty, there was no great rush. People seemed puzzled by which stations were open, which buses were running, and were moving from one to the other.

The news that anybody could be evacuated by applying at the Central Hall seemed to be leaking out only slowly. One woman midday was telling everybody she met, but another at the same time was telling her friends to go out to Romsey, 'there was still room there'.

(15) Angus Calder, The People's War: Britain 1939-45 (1969)

Methods of billeting varied greatly. In the well organized city of Cambridge, volunteers were waiting on the station platforms as each train came in to take the evacuees to 'dispersal centres' organized in different wards, and efforts were made to keep school parties together. In many areas, however, local householders had assembled to pick their evacuees when the trains or buses arrived, and 'Scenes reminiscent of a cross between an early Roman slave market and Selfridge's bargain basement ensued. Potato farmers selected husky lads; girls often or twelve who could lend a hand in the house were naturally much in demand; nicely dressed children were whisked away by local bigwigs. Those who got 'second pick' were often resentful, and there was likely to be a residue of unwholesome looking waifs whom nobody wanted, but whom somebody would have to take when the billeting officer began to mutter about compulsory powers. The alternative was usually a more or less haphazard distribution of children by the billeting officer and his helpers.

Social mismatching was inherent in the scheme. The official evacuees came disproportionately from the poorest strata of urban society, for several reasons. Firstly, the well-to-do were more likely to have made their own arrangements. Secondly, the evacuation areas were mostly areas of high population density, where overcrowding was at its worst, while the wealthier suburbs were often classified as 'neutral' areas. Thirdly, the poorer classes had maintained a higher birth rate than their social superiors. Social surveys of several provincial towns in the 1930s had suggested that while twelve to fifteen per cent of families were living below the poverty line, they included twenty-two to thirty per cent of the children. Large families, then as always, were a contributory cause of much poverty. And it is clear from detailed studies of evacuation in several areas that parents with only one or two children were less likely to send them away, and swifter to bring them back, than those with five or six; the smaller the family, the more it clung together.

As for the other half of the experiment, there was a shortage of housing, sometimes very acute, in the country as well as in the towns. Those with room to spare would be found disproportionately among the well-to-do. A Scottish survey suggested that only four out often evacuees from the overwhelmingly working-class town of Clydebank went to families judged to be working-class, and a third went to homes which were assessed as 'wealthy'. In many cases, like was matched with like, and working-class families took working-class children into environments much like those which they had known at home.