Slave Ships

An estimated 15 million Africans were transported to the Americas between 1540 and 1850. To maximize their profits slave merchants carried as many slaves as was physically possible on their ships. By the 17th century slaves could be purchased in Africa for about $25 and sold in the Americas for about $150. After the slave-trade was declared illegal, prices went much higher. Even with a death-rate of 50 per cent, merchants could expect to make tremendous profits from the trade.

The journey from Africa to the West Indies or North America Usually took about two months. One study shows that the slave ship provided an average of about seven square feet per slave. Gad Heuman and James Walvin, the authors of The Atlantic Slave Trade (2003) have argued that: "About half of all deaths were from stomach complaints (notably dysentery) and fevers brought on board from Africa, and made worse by the ships' conditions. A substantial proportion of slave deaths took place on the African coast, in the period when the captain was trying to fill his ship's holds with other slaves. The white crews of the slave ships also suffered unusually high death rates (again, worst on the African coast), though that too declined with time. In addition, there were always the unpredictable attacks of diseases and ailments which could cause havoc at sea, in the filth of the slave quarters.... We know of rebellions on more than 300 voyages, and of violent incidents on the African coast."

Thomas Phillips, a slave-ship captain, wrote an account of his activities in A Journal of a Voyage (1746): "I have been informed that some commanders have cut off the legs or arms of the most willful slaves, to terrify the rest, for they believe that, if they lose a member, they cannot return home again: I was advised by some of my officers to do the same, but I could not be persuaded to entertain the least thought of it, much less to put in practice such barbarity and cruelty to poor creatures who, excepting their want of Christianity and true religion (their misfortune more than fault), are as much the works of God's hands, and no doubt as dear to him as ourselves."

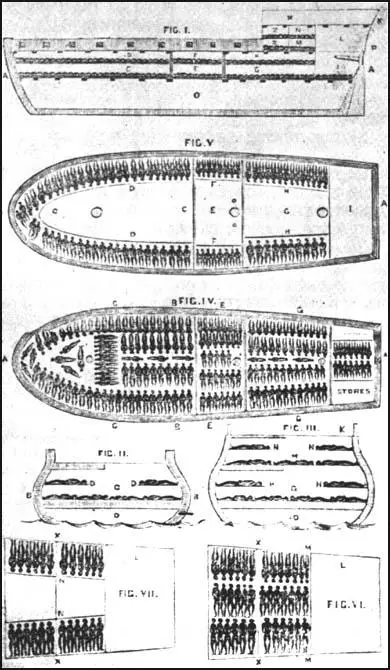

John Newton was a slave-captain between 1747 and 1754. He wrote in Thoughts upon the African Slave Trade (1787): "With our ships, the great object is, to be full. When the ship is there, it is thought desirable, she should take as many as possible. The cargo of a vessel of a hundred tons, or little more, is calculated to purchase from two hundred and twenty to two hundred and fifty slaves. Their lodging-rooms below the deck, which are three (for the men, the boys, and the women) besides a place for the sick, are sometimes more than five feet high, and sometimes less; and this height is divided towards the middle, for the slaves lie in two rows, one above the other, on each side of the ship, close to each other, like books upon a shelf. I have known them so close, that the shelf would not, easily, contain one more."

Working on a slave-ship could be very profitable. James Irving was a surgeon on the ship Vulture that sailed to Jamaica in November 1782. It has been argued by Suzanne Schwarz:, the author of Slave Captain: The Career of James Irving in the Liverpool Slave Trade (1995): "Assuming that Irving was paid £4 wages a month, together with the value of two privilege slaves and one shilling head money for each of the 592 slaves delivered alive to the West Indies, it is likely that Irving earned approximately £140 from this voyage. This is consistent with the average voyage earnings of slave-ship surgeons in the late eighteenth century, which were typically between £100 and £150."

In 1787 Thomas Clarkson and Granville Sharp formed the Society for the Abolition of the Slave Trade. Of the twelve members on the committee, nine were Quakers. Influential figures such as John Wesley and Josiah Wedgwood gave their support to the campaign. Later they persuaded William Wilberforce, the MP for Hull, to be their spokesman in the House of Commons. Clarkson was given the responsibility of collecting information to support the abolition of the slave trade. It is estimated that he was to ride some 35,000 miles in the next seven years. His work included interviewing 20,000 sailors and obtaining equipment used on the slave-ships such as iron handcuffs, leg-shackles, thumb screws, instruments for forcing open slave's jaws and branding irons. The misery which the slaves endure in consequence of too close a stowage is not easy to describe.

In 1787 Clarkson published his pamphlet, A Summary View of the Slave Trade and of the Probable Consequences of Its Abolition. He argued: "I have heard them (slaves) frequently complaining of heat, and have seen them fainting, almost dying for want of water. Their situation is worse in rainy weather. We do everything for them in our power. In all the vessels in which I have sailed in the slave trade, we never covered the gratings with a tarpawling, but made a tarpawling awning over the booms, but some were still panting for breath."

Slaves also began to publish their accounts of being aboard slave-ships. Ottobah Cugoano was only a child when he was taken from Africa: "We were taken in the ship that came for us, to another that was ready to sail from Cape Coast. When we were put into the ship, we saw several black merchants coming on board, but we were all drove into our holes, and not suffered to speak to any of them. In this situation we continued several days in sight of our native land. And when we found ourselves at last taken away, death was more preferable than life; and a plan was concerted amongst us, that we might burn and blow up the ship, and to perish all together in the flames: but we were betrayed by one of our own countrywomen, who slept with some of the headmen of the ship, for it was common for the dirty filthy sailors to take the African women and lie upon their bodies; but the men were chained and pent up in holes. It was the women and boys which were to burn the ship, with the approbation and groans of the rest; though that was prevented, the discovery was likewise a cruel bloody scene."

Olaudah Equiano was captured and sold as a slave in Benin. He wrote about his experiences in The Life of Olaudah Equiano the African (1789): "I was soon put down under the decks, and there I received such a greeting in my nostrils as I had never experienced in my life; so that, with the loathsomeness of the stench, and crying together, I became so sick and low that I was not able to eat, nor had I the least desire to taste anything. I now wished for the last friend, death, to relieve me; but soon, to my grief, two of the white men offered me eatables; and, on my refusing to eat, one of them held me fast by the hands, and laid me across, I think, the windlass, and tied my feet, while the other flogged me severely. The white people looked and acted, as I thought, in so savage a manner; for I had never seen among my people such instances of brutal cruelty. The closeness of the place, and the heat of the climate, added to the number in the ship, which was so crowded that each had scarcely room to turn himself, almost suffocated us. The air soon became unfit for respiration, from a variety of loathsome smells, and brought on a sickness among the slaves, of which many died. The wretched situation was again aggravated by the chains, now unsupportable, and the filth of the necessary tubs, into which the children often fell, and were almost suffocated. The shrieks of the women, and the groans of the dying, rendered the whole a scene of horror almost inconceivable."

A House of Commons committee in 1788 discovered that one slave-ship, The Brookes, was originally built to to carry a maximum of 451 people, but was carrying over 600 slaves from Africa to the Americas. "Chained together by their hands and feet, the slaves had little room to move." It has been estimated that only about half of the slaves taken from Africa became effective workers in the Americas. A large number of slaves died on the journey from diseases such as smallpox and dysentery. Others committed suicide by refusing to eat. Many of the slaves were crippled for life as a consequence of the way they were chained up on the ship.

Thomas Clarkson met Alexander Falcolnbridge, a former surgeon on board a slave ship. Falconbridge was willing to testify publicly about the way slaves were treated. He accompanied Clarkson to Liverpool where he acted as his bodyguard. Clarkson later called him "an athletic and resolute-looking man". In 1790 Falconbridge gave evidence to a privy council committee, and underwent four days of questions by a House of Commons committee. He explained how badly the slaves were treated on the ships: "The men, on being brought aboard the ship, are immediately fastened together, two and two, by handcuffs on their wrists and by irons rivetted on their legs. They are then sent down between the decks and placed in an apartment partitioned off for that purpose.... They are frequently stowed so close, as to admit of no other position than lying on their sides. Nor will the height between decks, unless directly under the grating, permit the indulgence of an erect posture; especially where there are platforms, which is generally the case. These platforms are a kind of shelf, about eight or nine feet in breadth, extending from the side of the ship toward the centre. They are placed nearly midway between the decks, at the distance of two or three feet from each deck, Upon these the Negroes are stowed in the same manner as they are on the deck underneath."

Thomas Trotter, a physician working on the slave-ship, Brookes, told the committee: "The slaves that are out of irons are locked spoonways and locked to one another. It is the duty of the first mate to see them stowed in this manner every morning; those which do not get quickly into their places are compelled by the cat and, such was the situation when stowed in this manner, and when the ship had much motion at sea, they were often miserably bruised against the deck or against each other. I have seen their breasts heaving and observed them draw their breath, with all those laborious and anxious efforts for life which we observe in expiring animals subjected by experiment to bad air of various kinds."

James Irving worked on slave-ships for nine years. It has been claimed by his biographer that "during his career he was involved in a number of voyages accounting for the delivery of some 3,000 slaves to the Americas". In May 1786 Irving sailed to Tobago. He wrote to his wife that "our black cattle are intolerably noisy and I'm almost melted in the midst of five or six hundred of them." David Richardson has argued: "Irving's insensitvity suggests that, even at a time when moral outrage in Britain at the enslavement of Africans was spreading, participation in the slave trade was still capable of promoting racism and blinding otherwise apparently quite caring individuals to the appalling suffering that they were helping to inflict on others."

Thomas Clarkson pointed out: "Men in their first voyages usually disliked the trade; and, if they were happy enough then to abandon it, they usually escaped the disease of a hardened heart. But if they want a second and a third time, their disposition became gradually changed... Now, if we consider that persons could not easily become captains (and to these the barbarities were generally chargeable by actual perpetration, or by consent) till they had been two or three voyages in this employ, we shall see the reason why it would be almost a miracle, if they, who were thus employed in it, were not rather to become monsters, than to continue to be men."

Some captains, like Hugh Crow, agreed with the regulation of the slave-trade. However, he rejected the criticism of William Wilberforce: "His proposition... that badges should be worn by African captains, who toiled at the risk of their lives for the accommodation of our colonies, and that he and others might enjoy their ease at home, was impertinent as well as ungracious; and his regulation that captains should land their cargoes without losing a certain number of black slaves, was absolutely ridiculous. Not a word was said about the white slaves, the poor sailors; these might die without regret.... And with respect to the insinuation thrown out, in this country, that African captains sometimes threw their slaves overboard, it is unworthy of notice, for it goes to impute an absolute disregard of self interest, as well as of all humanity. In the African trade, as in all others, there were individuals bad as well as good, and it is but justice to discriminate, and not condemn the whole for the delinquencies of a few."

John Newton wrote in Thoughts upon the African Slave Trade (1787): "Epidemical fevers and fluxes, which fill the ship with noisome and noxious effluvia, often break out, infect the seamen likewise, and the oppressors, and the oppressed, fall by the same stroke. I believe, nearly one half of the slaves on board, have, sometimes, died; and that the loss of a third part, in these circumstances, is not unusual. The ship, in which I was mate, left the coast with two hundred and eighteen slaves on board; and though we were not much affected by epidemical disorders, I find, by my journal of that voyage (now before me) that we buried sixty-two on our passage to South Carolina, exclusive of those which died before we left the coast, of which I have no account. I believe, upon an average between the more healthy, and the more sickly voyages, and including all contingencies, One fourth of the whole purchase may be allotted to the article of mortality. That is, if the English ships purchase sixty thousand slaves annually, upon the whole extent of the coast, the annual loss of lives cannot be much less than fifteen thousand."

In 1796 Mungo Park joined an American slave ship, Charlestown, bound for South Carolina. He later recalled the journal: "The number of slaves received on board this vessel... was one hundred and thirty; of whom about twenty-five had been, I suppose, of free condition in Africa, as most of them, being Bushreens, could write a little Arabic. Nine of them had become captives in the religious war between Abdulkader and Damel.... My conversation with them, in their native language, gave them great comfort; and as the surgeon was dead, I consented to act in a medical capacity in his room for the remainder of the voyage. They had in truth need of every consolation in my power to bestow; not that I observed any wanton acts of cruelty practised either by the master or the seamen towards them; but the mode of confining and securing Negroes in the American slave ships, owing chiefly to the weakness of their crews, being abundantly more rigid and severe than in British vessels employed in the same traffic, made these poor creatures to suffer greatly, and a general sickness prevailed amongst them. Besides the three who died on the Gambia, and six or eight while we remained at Goree, eleven perished at sea, and many of the survivors were reduced to a very weak and emaciated condition."

Stephen D. Behrendt, carried out a study of 1,709 muster rolls for Liverpool slave voyages between 1780 and 1807. He discovered that 17.8 per cent of original crew died (10,439 out of 58,778). The time spent on the African coast was particularly dangerous. Although large numbers of men died from drowning, Behrendt discovered that various types of fevers accounted for the majority of deaths. Gastrointestinal diseases including flux, dysentery and diarrhoea accounted for 11 per cent of the sample.

After William Wilberforce retired in 1825, Thomas Fowell Buxton became the leader of the campaign in the House of Commons. Buxton, with the help of Thomas Clarkson, set about collecting information about slavery and compiling demographic statistics. In a speech on 23rd May 1826 he described the conditions on board a slave-ship: "The voyage, the horrors of which are beyond description. For example, the mode of packing. The hold of a slave vessel is from two to four feet high. It is filled with as many human beings as it will contain. They are made to sit down with their heads between their knees: first, a line is placed close to the side of the vessel; then another line, and then the packer, armed with a heavy club, strikes at the feet of this last line in order to make them press as closely as possible against those behind... Thus it is suffocating for want of air, starving for want of food, parched with thirst for want of water, these poor creatures are compelled to perform a voyage of fourteen hundred miles. No wonder the mortality is dreadful!"

Primary Sources

(1) Ottobah Cugoano, Narrative of the Enslavement of a Native of Africa (1787)

We were taken in the ship that came for us, to another that was ready to sail from Cape Coast. When we were put into the ship, we saw several black merchants coming on board, but we were all drove into our holes, and not suffered to speak to any of them. In this situation we continued several days in sight of our native land. And when we found ourselves at last taken away, death was more preferable than life; and a plan was concerted amongst us, that we might burn and blow up the ship, and to perish all together in the flames: but we were betrayed by one of our own countrywomen, who slept with some of the headmen of the ship, for it was common for the dirty filthy sailors to take the African women and lie upon their bodies; but the men were chained and pent up in holes. It was the women and boys which were to burn the ship, with the approbation and groans of the rest; though that was prevented, the discovery was likewise a cruel bloody scene.

But it would be needless to give a description of all the horrible scenes which we saw, and the base treatment which we met with in this dreadful captive situation, as the similar cases of thousands, which suffer by this infernal traffic, are well known. Let it suffice to say that I was thus lost to my dear indulgent parents and relations, and they to me. All my help was cries and tears, and these could not avail, nor suffered long, till one succeeding woe and dread swelled up another. Brought from a state of innocence and freedom, and, in a barbarous and cruel manner, conveyed to a state of horror and slavery, this abandoned situation may be easier conceived than described.

(2) Olaudah Equiano, was captured and sold as a slave in the kingdom of Benin in Africa. He wrote about his experiences in The Life of Olaudah Equiano the African (1789)

The first object which saluted my eyes when I arrived on the coast, was the sea, and a slave ship, which was then riding at anchor, and waiting for its cargo. These filled me with astonishment, which was soon converted into terror, when I was carried on board. I was immediately handled, and tossed up to see if I were sound, by some of the crew; and I was now persuaded that I had gotten into a world of bad spirits, and that they were going to kill me.

I was soon put down under the decks, and there I received such a greeting in my nostrils as I had never experienced in my life; so that, with the loathsomeness of the stench, and crying together, I became so sick and low that I was not able to eat, nor had I the least desire to taste anything. I now wished for the last friend, death, to relieve me; but soon, to my grief, two of the white men offered me eatables; and, on my refusing to eat, one of them held me fast by the hands, and laid me across, I think, the windlass, and tied my feet, while the other flogged me severely.

The white people looked and acted, as I thought, in so savage a manner; for I had never seen among my people such instances of brutal cruelty. The closeness of the place, and the heat of the climate, added to the number in the ship, which was so crowded that each had scarcely room to turn himself, almost suffocated us.

The air soon became unfit for respiration, from a variety of loathsome smells, and brought on a sickness among the slaves, of which many died. The wretched situation was again aggravated by the chains, now unsupportable, and the filth of the necessary tubs, into which the children often fell, and were almost suffocated. The shrieks of the women, and the groans of the dying, rendered the whole a scene of horror almost inconceivable.

(3) Zamba Zembola, The Life and Adventures of Zamba and African Slave (1847)

Captain Winton told me in the course of our voyage, that, in the early part of his experience in the slave-trade, he had seen slaves where they were literally packed on the top of each other; and consequently, from ill air, confinement, and scanty or unwholesome provision, disease was generated to such an extent that in several cases he had known only one-half survive to the end of the voyage; and these, as he termed it, in a very unmarketable condition. He found, therefore, that, by allowing them what he called sufficient room and good provisions, with kind treatment, his speculations turned out much better in regard to the amount of dollars received; and that was all he cared for.

After being about 15 days out to sea a heavy squall struck the ship. The poor slaves below, altogether unprepared for such an occurrence, were mostly thrown to the side, where they lay heaped on the top of each other; their fetters rendered many of them helpless, and before they could be arranged in their proper places, and relived from their pressure on each other, it was found that 15 of them were smothered or crushed to death. The captain seemed considerably vexed; but the only grievance to him was the sudden loss of some five or six thousand dollars.

(4) Thomas Phillips, a slave-ship captain, wrote an account of his activities in A Journal of a Voyage (1746)

I have been informed that some commanders have cut off the legs or arms of the most willful slaves, to terrify the rest, for they believe that, if they lose a member, they cannot return home again: I was advised by some of my officers to do the same, but I could not be persuaded to entertain the least thought of it, much less to put in practice such barbarity and cruelty to poor creatures who, excepting their want of Christianity and true religion (their misfortune more than fault), are as much the works of God's hands, and no doubt as dear to him as ourselves.

(5) Thomas Clarkson interviewed a sailor who worked on a slave-ship and published the account in his book, Essay on the Slave Trade (1789)

The misery which the slaves endure in consequence of too close a stowage is not easy to describe. I have heard them frequently complaining of heat, and have seen them fainting, almost dying for want of water. Their situation is worse in rainy weather. We do everything for them in our power. In all the vessels in which I have sailed in the slave trade, we never covered the gratings with a tarpawling, but made a tarpawling awning over the booms, but some were still panting for breath.

(6) John Newton, Thoughts upon the African Slave Trade (1787)

I have, to the best, of my knowledge, pointed out the principal sources, of that immense supply of slaves, which furnishes so large an exportation every year. If all that are taken on board the ships, were to survive the voyage, and be landed in good order, possibly the English, French, and Dutch islands, and colonies, would be soon overstocked, and fewer ships would sail to the Coast. But a large abatement must be made for mortality. After what I have already said of their treatment, I shall now, that I am again to consider them on board the ships, confine myself to this point.

In the Portuguese ships, which trade from Brazil to the Gold Coast and Angola, I believe, a heavy mortality is not frequent. The slaves have room, they are not put in irons, (I speak from information only) and are humanely treated.

With our ships, the great object is, to be full. When the ship is there, it is thought desirable, she should take as many as possible. The cargo of a vessel of a hundred tons, or little more, is calculated to purchase from two hundred and twenty to two hundred and fifty slaves. Their lodging-rooms below the

deck, which are three (for the men, the boys, and the women) besides a place for the sick, are sometimes more than five feet high, and sometimes less; and this height is divided towards the middle, for the slaves lie in two rows, one above the other, on each side of the ship, close to each other, like books upon a shelf. I have known them so close, that the shelf would not, easily, contain one more.

And I have known a white man sent down among the men, to lay them in these rows to the greatest advantage, so that as little space as possible might be lost. Let it be observed, that the poor creatures, thus cramped for want of room, are likewise in irons, for the most part both hands and feet, and two together, which makes it difficult for them to turn or move, to attempt either to rise or to lie down, without hurting themselves, or each other. Nor is the motion of the ship, especially her heeling, or stoop on one side, when under sail, to be admitted; for this, as they lie athwart, or across the ship, adds to the uncomfortableness of their lodging, especially to those who lie on the leeward, or leaning side of the vessel.

The heat and the smell of these rooms, when the weather will not admit of the slaves being brought upon deck, and of having their rooms cleaned every day, would be, almost, insupportable, to a person not accustomed to them. If the slaves and their rooms can be constantly aired, and they are not detained too long on board, perhaps there are not many die; but the contrary is often their lot. They are kept down, by the weather, to breathe a hot and corrupted air, sometimes for a week: this, added to the galling of their irons, and the despondency which seizes their spirits, when thus confined, soon becomes fatal. And every morning, perhaps, more instances than one are found, of the living and the dead, like the Captives of Mezentius, fastened together.

Epidemical fevers and fluxes, which fill the ship with noisome and noxious effluvia, often break out, infect the seamen likewise, and the oppressors, and the oppressed, fall by the same stroke. I believe, nearly one half of the slaves on board, have, sometimes, died; and that the loss of a third part, in these circumstances, is not unusual. The ship, in which I was mate, left the coast with two hundred and eighteen slaves on board; and though we were not much affected by epidemical disorders, I find, by my journal of that voyage (now before me) that we buried sixty-two on our passage to South Carolina, exclusive of those which died before we left the coast, of which I have no account.

I believe, upon an average between the more healthy, and the more sickly voyages, and including all contingencies, One fourth of the whole purchase may be allotted to the article of mortality. That is, if the English ships purchase sixty thousand slaves annually, upon the whole extent of the coast, the annual loss of lives cannot be much less than fifteen thousand.

(7) Dr. Thomas Trotter, a physician working on the slave-ship, Brookes, was interviewed by a House of Commons committee in 1790. This is how he replied when he was asked if the "slaves had room to turn themselves".

No. The slaves that are out of irons are locked spoonways and locked to one another. It is the duty of the first mate to see them stowed in this manner every morning; those which do not get quickly into their places are compelled by the cat and, such was the situation when stowed in this manner, and when the ship had much motion at sea, they were often miserably bruised against the deck or against each other. I have seen their breasts heaving and observed them draw their breath, with all those laborious and anxious efforts for life which we observe in expiring animals subjected by experiment to bad air of various kinds.

(8) Alexander Falcolnbridge, An Account of the Slave Trade on the Coast of Africa (1790)

From the time of the arrival of the ships to their departure, which is usually near three months, scarce a day passes without some negroes being purchased, and carried on board; sometimes in small, and sometimes in larger numbers. The whole number taken on board, depends, in a great measure, on circumstances. In a voyage I once made, our stock of merchandize was exhausted in the purchase of about 380 negroes, which was expected to have procured 500. The number of English and French ships then at Bonny, had so far raised the price of negroes, as to occasion this difference.... I was once upon the coast of Angola, also, when there had not been a slave ship at the river Ambris for five years previous to our arrival, although a place to which many usually resort every year. The failure of the trade for that period, as far as we could learn, had no other effect than to restore peace and confidence among the natives, which, upon the arrival of ships, is immediately destroyed by the inducement then held forth in the purchase of slaves.....

Previous to my being in this employ I entertained a belief, as many others have done, that the kings and principal men bred Negroes for sale as we do cattle. During the different times I was in the country, I took no little pains to satisfy myself in this particular; but notwithstanding I made many inquires, I was not able to obtain the least intelligence of this being the case.... All the information I could procure confirms me in the belief that to kidnapping, and to crimes (and many of these fabricated as a pretext) the slave trade owes its chief support....

(9) Mungo Park, Travels to the Interiors of Africa (1799)

No European vessel had arrived at Gambia for many months previous to my return from the interior; and as the rainy season was now setting in, I persuaded Karfa to return to his people at Jindey. He parted with me on the 14th with great tenderness; but as I had little hopes of being able to quit Africa for the remainder of the year, I told him, as the fact was, that I expected to see him again before my departure. In this, however, I was luckily disappointed; and my narrative now hastens to its conclusion; for on the 15th, the ship Charlestown, an American vessel, commanded by Mr. Charles Harris, entered the river. She came for slaves, intending to touch at Goree to fill up; and to proceed from thence to South Carolina. As the European merchants on the Gambia had at this time a great many slaves on hand, they agreed with the captain to purchase the whole of his cargo, consisting chiefly of rum and tobacco, and deliver him slaves to the amount, in the course of two days. This afforded me such an opportunity of returning (though by a circuitous route) to my native country, as I thought was not to be neglected. I therefore immediately engaged my passage in this vessel for America; and having taken leave of Dr. Laidley, to whose kindness I was so largely indebted, and my other friends on the river, I embarked at Kaye on the 17th day of June.

The number of slaves received on board this vessel, both on the Gambia and at Goree, was one hundred and thirty; of whom about twenty-five had been, I suppose, of free condition in Africa, as most of them, being Bushreens, could write a little Arabic. Nine of them had become captives in the religious war between Abdulkader and Damel, mentioned in the latter part of the preceding chapter; two of the others had seen me as I passed through Bondou, and many of them had heard of me in the interior countries. My conversation with them, in their native language, gave them great comfort; and as the surgeon was dead, I consented to act in a medical capacity in his room for the remainder of the voyage. They had in truth need of every consolation in my power to bestow; not that I observed any wanton acts of cruelty practised either by the master or the seamen towards them; but the mode of confining and securing Negroes in the American slave ships, owing chiefly to the weakness of their crews, being abundantly more rigid and severe than in British vessels employed in the same traffic, made these poor creatures to suffer greatly, and a general sickness prevailed amongst them. Besides the three who died on the Gambia, and six or eight while we remained at Goree, eleven perished at sea, and many of the survivors were reduced to a very weak and emaciated condition.

In the midst of these distresses, the vessel, after having been three weeks at sea, became so extremely leaky, as to require constant exertion at the pumps. It was found necessary, therefore, to take some of the ablest of the Negro men out of irons, and employ them in this labour; in which they were often worked beyond their strength. This produced a complication, of miseries not easily to be described. We were, however, relieved much sooner than I expected; for the leak continuing to gain upon us, notwithstanding our utmost exertions to clear the vessel, the seamen insisted on bearing away for the West Indies, as affording the only chance of saving our lives. Accordingly, after some objections on the part of the master, we directed our course for Antigua, and fortunately made that island in about thirty-five days after our departure from Goree. Yet even at this juncture we narrowly escaped destruction; for on approaching the north-west side of the island, we struck on the Diamond Rock, and got into St John's harbour with great difficulty. The vessel was afterwards condemned as unfit for sea, and the slaves, as I have heard, were ordered to be sold for the benefit of the owners.

(10) James Irving, letter to Mary Irving (2nd December 1786)

We have been in Tobago since the 25th November and have not yet disposed of any of our very disagreeable cargo... I'm nearly wearied of this unnatural accursed trade, and think... when convenience suits of adopting some other mode of life, although I'm fully sensible and aware of the difficulties attending any new undertaking, yet I will at least look around me.

(11) Thomas Fowell Buxton, speech in the House of Commons (9th May, 1826)

The voyage, the horrors of which are beyond description. For example, the mode of packing. The hold of a slave vessel is from two to four feet high. It is filled with as many human beings as it will contain. They are made to sit down with their heads between their knees: first, a line is placed close to the side of the vessel; then another line, and then the packer, armed with a heavy club, strikes at the feet of this last line in order to make them press as closely as possible against those behind. And so the packing goes on; until, to use the expression of an eyewitness, "they are wedged together in one mass of living corruption". Thus it is suffocating for want of air, starving for want of food, parched with thirst for want of water, these poor creatures are compelled to perform a voyage of fourteen hundred miles. No wonder the mortality is dreadful!

(12) Gad Heuman and James Walvin, The Atlantic Slave Trade (2003)

There had undoubtedly been a number of slave deaths before reaching the African coast - on the protracted movement of slaves within Africa - though the evidence for this is sparse. We also know that a considerable number of slaves died after landfall in the Americas, not surprising perhaps given the levels of sickness on board the Atlantic vessels. What is clear is that European and American slave traders generally sought to preserve the lives and health of their African slaves. They were, after all - and however crude it may seem - a valuable investment. Moreover, many slave traders tried to improve the shipboard conditions, with the result that slave mortality fell on all European and American ships over time. Yet there remains the unavoidable fact that slaves continued to die at a rate which would have horrified shippers of military or emigrant Europeans. And they died "not only from disease and accident, but from rebellion, suicide, and natural disasters". We know of rebellions on more than 300 voyages, and of violent incidents on the African coast. There were some 443 shipwrecks of slave ships, while more than 800 vessels were seized by privateers. In the nineteenth century 1,871 slave ships were impounded by anti-slave-trade patrols. Yet the great majority of slaves packed into the slave ships on the African coast arrived, whatever their condition, for sale to the slave owners of the Americas.

Landfall brought relief to the crew but almost certainly more fears and uncertainties among the Africans. They were sold as soon as was possible, having been prepared on board ship to look fit for sale and work. They were sold either on the ship or at a local market. Sicker slaves, of course, took longer to sell. The slave traders usually accepted a percentage of the agreed price, the rest to be paid later, normally in local produce. Contrary to popular belief, the slave ships returned to Europe not loaded with colonial produce but often in ballast (normal cargo vessels shipped colonial produce back to Europe), and with a greatly reduced crew, many of whom were shabbily treated and simply paid off in the Americas. On return to Britain (or elsewhere), the slave captain's main task was securing repayment on his outlay, and, over the next few years, selling goods arriving from the Americas from people who had bought his slave cargo. It was a protracted business that might last up to six years. And yet there seems to have been no reluctance among shippers and investors to involve themselves in the Atlantic slave trade. They clearly thought that it had profitable potential.

Despite some highly inflated estimates, the slave trade yielded profits averaging about 10 per cent. And there seem to have been important linkages between the African trade and early European industry. The slave trade made use of and expanded complex systems of international finance and credit, and became central to a genuinely global economy which linked the trades of Asia to those of Africa, Europe and the Americas. At the heart of this Atlantic slave system was a consumer revolution which saw Europeans consuming the crops from the slave colonies of the Americas in enormous volumes. All this was made possible by the imported Africans. In the words of Herbert Klein, "Until European immigrants replaced them in the late nineteenth century, it was African slaves who enabled this consumption revolution to occur. Without that labor most of America would never have developed at the pace it did."