On this day on 26th July

On this day in 1856 George Bernard Shaw, the third and youngest child, and only son, of George Carr Shaw (1815–1885) and Lucinda Gurly (1830–1913), was born at 3 Upper Synge Street (later 33 Synge Street), Dublin. Shaw's father, a corn merchant, was also an alcoholic and therefore there was very little money to spend on George's education. George went to local schools but never went to university and was largely self-taught.

Shaw began work on 26th October 1871, when he was fifteen, as a junior clerk in a Dublin estate agency run by two brothers, Charles Uniacke and Thomas Courtney Townshend, at a salary of £18 a year. He later recalled that he worked in " a stuffy little den counting another man's money… I enter and enter, and add and add, and take money and give change, and fill cheques and stamp receipts". He added that it was a "damnable waste of human life". According to his biographer, Stanley Weintraub: "While he performed his drudgery so conscientiously over fifteen months that his wages rose to £24." His parents moved to London and Shaw joined them in March 1876.

Shaw hoped to become a writer and during the next seven years wrote five unsuccessful novels. He was more successful with his journalism and contributed to Pall Mall Gazette. Shaw got on well with the newspaper's campaigning editor, William Stead, who attempted to use the power of the popular press to obtain social reform.

In 1882 Shaw heard Henry George lecture on land nationalization. This had a profound effect on Shaw and helped to develop his ideas on socialism. Shaw now joined the Social Democratic Federation and its leader, H. H. Hyndman, introduced him to the works of Karl Marx. Shaw was convinced by the economic theories in Das Kapital but was aware that it would have little impact on the working class. He later wrote that although the book had been written for the working man, "Marx never got hold of him for a moment. It was the revolting sons of the bourgeois itself - Lassalle, Marx, Liebknecht, Morris, Hyndman, Bax, all like myself, crossed with squirearchy - that painted the flag red. The middle and upper classes are the revolutionary element in society; the proletariat is the conservative element."

Shaw became an active member of the Social Democratic Federation (SDF), and became friends with others in the movement including William Morris, Eleanor Marx, Annie Besant, Walter Crane, Edward Aveling and Belfort Bax. In May 1884 Shaw joined the Fabian Society and the following year, the Socialist League, an organisation that had been formed by Morris and Marx after a dispute with H. H. Hyndman, the leader of the SDF.

George Bernard Shaw gave lectures on socialism on street corners and helped distribute political literature. On 13th November he took part in a demonstration in London that resulted in the Bloody Sunday Riot. However, he always felt uncomfortable with trade union members and preferred debate to action.

By 1886, Shaw tended to concentrate his efforts on the work that he did with the Fabian Society. The society that included Edward Carpenter, Annie Besant, Walter Crane, Sidney Webb and Beatrice Webb believed that capitalism had created an unjust and inefficient society. They agreed that the ultimate aim of the group should be to reconstruct "society in accordance with the highest moral possibilities". As Shaw pointed out: "Some men see things as they are and say why. I dream things that never were and say why not."

The Fabian Society rejected the revolutionary socialism of the Social Democratic Federation and were concerned with helping society to move to a socialist society "as painless and effective as possible". This is reflected in the fact that the group was named after the Roman General, Quintus Fabius Maximus, who advocated the weakening the opposition by harassing operations rather than becoming involved in pitched battles.

The Fabian group was a "fact-finding and fact-dispensing body" and they produced a series of pamphlets on a wide variety of different social issues. Many of these were written by Shaw including The Fabian Manifesto (1884), The True Radical Programme (1887), Fabian Election Manifesto (1892), The Impossibilities of Anarchism (1893), Fabianism and the Empire (1900) and Socialism for Millionaires (1901). Max Beerbohm, who did not share Shaw's socialist beliefs, described him as "the most brilliant and remarkable journalist in London."

Frank Harris appointed Shaw as drama critics for The Fortnightly Review. He also published long articles by Shaw including Socialism and Superior Brains. Harris described Shaw as "thin as a rail, with a long, bony, bearded face. His untrimmed beard was reddish, though his hair was fairer. He was dressed carelessly in tweeds... His entrance into the room, his abrupt movements - as jerky as the ever-changing mind - his perfect unconstraint, his devilish look, all showed a man very conscious of his ability, very direct, very sharply decisive."

Shaw supported women's rights, and in 1891 wrote: "Unless woman repudiates her womanliness, her duty to her husband, to her children, to society, to the law, and to everyone but herself, she cannot emancipate herself. It is false to say that woman is now directly the slave of man: she is the immediate slave of duty; and as man's path to freedom is strewn with the wreckage of the duties and ideals he has trampled on, so must hers be."

Beatrice Webb wrote in her diary: "Bernard Shaw is a marvellously smart witty fellow with a crank for not making money. I have never known a man use his pen in such a workmanlike fashion or acquire such a thoroughly technical knowledge of any subject upon which he gives an opinion. As to his character, I do not understand it. He has been for twelve years a devoted propagandist, hammering away at the ordinary routine of Fabian Executive work with as much persistence as Graham Wallas or Sidney (Webb). He is an excellent friend - at least to men - but beyond this I know nothing.... Adored by many women, he is a born philanderer. A vegetarian, fastidious but unconventional in his clothes, six foot in height with a lithe, broad-chested figure and laughing blue eyes. Above all a brilliant talker, and, therefore, a delightful companion."

Edith Nesbit was one of the many women who he tried to seduce. She wrote to a friend: "George Bernard Shaw... has a fund of dry Irish humour that is simply irresistible. He is a clever writer and speaker - is the grossest flatterer I ever met, is horribly untrustworthy as he repeats everything he hears, and does not always stick to the truth, and is very plain like a long corpse with dead white face - sandy sleek hair, and a loathsome small straggly beard, and yet is one of the most fascinating men I ever met."

Jack Grein was the founder of Independent Theatre. According to his biographer, John P. Wearing: "Grein's major achievement was establishing the Independent Theatre in London in 1891.... Grein endeavoured to stage plays of high literary and artistic value rejected by the commercial theatre or suppressed by the censor (whom the Independent Theatre circumvented by being a subscription society)." A great admirer of Henrik Ibsen his first production was Ghosts.

The following year Grein met Shaw. During a walk in Hammersmith Grein said he was disappointed that he had not discovered any good British playwrights. Shaw replied that he had written a play "that you'll never have the courage to produce". Grein asked to see the play. He later recalled: "I spent a long and attentive evening in sorting and deciphering it. I had never had a doubt as to my acceptance... But I could very well understand how little chance that play would have had with the average theatre manager."

Widower's Houses opened at the Royalty Theatre in Dean Street, Soho on 9th December, 1892. Michael Holroyd, the author of Bernard Shaw (1998), points out: "The novelty of Widowers' Houses lay in the anti-romantic use to which Shaw put theatrical cliché. When the father discovers his daughter in the arms of a stranger, he omits to horsewhip him, but pitches into negotiations over the marriage - and these negotiations reveal a naked money-for-social-position bargin." According to Holroyd: "At the end of the performance, Shaw hurried before the curtain to make a speech and was acclaimed with hisses. At the second and final performance, a matinee on 13th December, he again climbed on to the stage and, there being no critics present, was applauded."

This was followed by other plays by Ibsen including The Wild Duck, Rosmersholm and The Master Builder. Shaw later wrote: "The Independent Theatre is an excellent institution, simply because it is independent. The disparagers ask what it is independent of.... It is, of course, independent of commercial success.... If Mr Grein had not taken the dramatic critics of London and put them in a row before Ghosts and The Wild Duck, with a small but inquisitive and influential body of enthusiasts behind them, we should be far less advanced today than we are."

In his pamphlets George Bernard Shaw argued in favour of equality of income and advocated the equitable division of land and capital. Shaw believed that "property was theft" and believed like Karl Marx that capitalism was deeply flawed and was unlikely to last. However, unlike Marx, Shaw favoured gradualism over revolution. In a pamphlet, that he wrote in 1897 Shaw predicted that socialism "will come by prosaic installments of public regulation and public administration enacted by ordinary parliaments, vestries, municipalities, parish councils, school boards, etc."

Shaw worked closely with Sidney Webb in trying to establish a new political party that was committed to obtaining socialism through parliamentary elections. This view was expressed in their Fabian Society pamphlet A Plan on Campaign for Labour.

In 1893 Shaw was one of the Fabian Society delegates that attended the conference in Bradford that led to the formation of the Independent Labour Party. Three years later Shaw produced a report for the Trade Union Congress (TUC) that suggested a political party that had strong links with the trade union movement.

In 1894 Frank Harris was sacked by Frederick Chapman, the owner of the The Fortnightly Review, for publishing an article by Charles Malato, an anarchist who praised political murder as "propaganda… by deed". Harris now purchased The Saturday Review and once again appointed Shaw as his drama critic on a salary of £6 a week. Shaw later commented that was "not bad pay in those days" and added that Harris was "the very man for me, and I the very man for him". Shaw's hostile reviews led to some managements withdrawing their free seats. Some of the book reviewers were so severe that publishers cancelled their advertisements. Harris was forced to sell the journal for financial reasons in 1898. Michael Holroyd has argued: "There had been a number of libel cases and rumours of blackmail - later put down by Shaw to Harris's innocence of English business methods."

In January 1896 Beatrice Webb invited Shaw and Charlotte Payne-Townshend to their rented home in the village of Stratford St Andrew in Suffolk. Shaw took a strong liking to Charlotte. He wrote to Janet Achurch: "Instead of going to bed at ten, we go out and stroll about among the trees for a while. She, being also Irish, does not succumb to my arts as the unsuspecting and literal Englishwoman does; but we get on together all the better, repairing bicycles, talking philosophy and religion... or, when we are in a mischievous or sentimental humor, philandering shamelessly and outrageously." Beatrice wrote: "They were constant companions, pedaling round the country all day, sitting up late at night talking."

Shaw told Ellen Terry: "Kissing in the evening among the trees was very pleasant, but she knows the value of her unencumbered independence, having suffered a good deal from family bonds and conventionality before the death of her mother and the marriage of her sister left her free... The idea of tying herself up again by a marriage before she knows anything - before she has exploited her freedom and money power to the utmost."

When they returned to London she sent an affectionate letter to Shaw. He replied: "Don't fall in love: be your own, not mine or anyone else's.... From the moment that you can't do without me, you're lost... Never fear: if we want one another we shall find it out. All I know is that you made the autumn very happy, and that I shall always be fond of you for that."

Michael Holroyd has pointed out in his book, Bernard Shaw (1998): "Charlotte had an apprehension of sexual intercourse... Over the next eighteen months they seem to have found together a habit of careful sexual experience, reducing for her the risk of conception and preserving for him his subliminal illusions... Charlotte soon made herself almost indispensable to Shaw. She learnt to read his shorthand and to type, took dictation and helped him prepare his plays for the press."

Beatrice Webb recorded in her diary that Charlotte Payne-Townshend was clearly in love with George Bernard Shaw but she did not believe that he felt the same way: "I see no sign on his side of the growth of any genuine and steadfast affection." In July 1897 Charlotte proposed marriage. He rejected the idea because he was poor and she was rich and people might consider him a "fortune-hunter". He told Ellen Terry that the proposal was like an "earthquake" and "with shuddering horror and wildly asked the fare to Australia". Charlotte decided to leave Shaw and went to live in Italy.

In April 1898 George Bernard Shaw had an accident. According to Shaw his left foot swelled up "to the size of a church bell". He wrote to Charlotte complaining that he was unable to walk. When she heard the news she travelled back to visit him at his home in Fitzroy Square. Soon after she arrived on 1st May she arranged for him to go into hospital. Shaw had an operation that scraped the necrosed bone clean.

Shaw's biographer, Stanley Weintraub, has pointed out: "In the conditions of non-care in which he lived at 29 Fitzroy Square with his mother (the Shaws had moved again on 5 March 1887), an unhealed foot injury required Shaw's hospitalization. On 1 June 1898, while on crutches and recuperating from surgery for necrosis of the bone, Shaw married his informal nurse, Charlotte Frances Payne-Townshend, at the office of the registrar at 15 Henrietta Street, Covent Garden. He was nearly forty-two; the bride, a wealthy Irishwoman born at Londonderry on 20 January 1857, thus a half-year younger than her husband, resided in some style at 10 Adelphi Terrace, London, overlooking the Embankment." Shaw later told Wilfrid Scawen Blunt: "I thought I was dead, for it would not heal, and Charlotte had me at her mercy. I should never have married if I had thought I should get well."

On 27th February 1900 the Fabian Society joined with the Independent Labour Party, the Social Democratic Federation and trade union leaders to form the Labour Representation Committee (LRC). The LRC put up fifteen candidates in the 1900 General Election and between them they won 62,698 votes. Two of the candidates, Keir Hardie and Richard Bell won seats in the House of Commons. The party did even better in the 1906 election with twenty nine successful candidates. Later that year the LRC decided to change its name to the Labour Party.

George Bernard Shaw wrote several plays with political themes during this period. These plays dealt with issues such as poverty and women's rights and implied that socialism could help solve the problems created by capitalism. Max Beerbohm was a great supporter of the work of Shaw. Although he did not share Shaw's socialist beliefs, but considered him a great playwright. He was especially complimentary about Man and Superman (1902), which he considered to be his "masterpiece so far". He described it as the "most complete expression of the most distinct personality in current literature".

Beerbohm also liked John Bull's Other Island (1904): "Mr Shaw, it is insisted, cannot draw life: he can only distort it. All his characters are but so many incarnations of himself. Above all, he cannot write plays. He has no dramatic instinct, no theatrical technique... That theory might have held water in the days before Mr Shaw's plays were acted. Indeed, I was in the habit of propounding it myself... When I saw John Bull's Other Island I found that as a piece of theatrical construction it was perfect... to deny that he is a dramatist merely because he chooses for the most part, to get drama out of contrasted types of character and thought, without action, and without appeal to the emotions, seems to me both unjust and absurd. His technique is peculiar because his purpose is peculiar. But it is not the less technique."

Major Barbara was first performed on 28th November 1905. The play completely divided the critics. Desmond MacCarthy told his readers: "Mr Shaw has written the first play with religious passion for its theme and has made it real. That is a triumph no criticism can lessen." The Sunday Times said that Shaw was "the most original English dramatist of the day". However, The Morning Post described the play as a work of "deliberate perversity" without any "straightforward intelligible purpose". Whereas The Clarion claimed it was an "audacious propagandist drama".

In 1912 George Bernard Shaw began work on his play Pygmalion. His biographer, Stanley Weintraub, pointes out: "Although Shaw claimed that he had written a didactic play about phonetics, and its anti-heroic protagonist, Henry Higgins, is indeed a speech professional, what playgoers saw was a high comedy about love and class, about a cockney flower-girl from Covent Garden educated to pass as a lady, and the repercussions of the experiment... The First World War began as Pygmalion was nearing its hundredth sell-out performance, and gave Shaw an excuse to wind down the production."

Like many socialists, George Bernard Shaw opposed Britain's involvement in the First World War. He created a great deal of controversy with his provocative pamphlet, Common Sense About the War, which appeared on 14th November 1914 as a supplement to the New Statesman. It sold more than 75,000 copies before the end of the year and as a result he became a well-known international figure. However, given the patriotic mood of the country, his pamphlet created a great deal of hostility. Some of his anti-war speeches were banned from the newspapers, and he was expelled from the Dramatists' Club.

Kingsley Martin was one of those who went to hear Shaw speak at an anti-war meeting: "He made an indelible impression on me at this first meeting. I cannot recall what he spoke about. It mattered little. It was George Bernard Shaw you remembered; his physical magnificence, splendid bearing, superb elocution, unexpected Irish brogue, and continuous wit were the chief memories of his speech. He would give his nose a thoughtful twitch between his thumb and finger while the audience laughed. He was one of the best speakers I ever heard."

Shaw's status as a playwright continued to grow after the war and plays such as Heartbreak House (1919), Back to Methuselah (1921), Saint Joan (1923), The Apple Cart (1929) and Too True to be Good (1932) were favourably received by the critics and 1925 he was awarded the Nobel prize for literature. Cyril Joad was one of those who believed Shaw was a genius: "Shaw became for me a kind of god. I considered that he was not only the greatest English writer of his time (I still think that), but the greatest English writer of all time (and I am not sure that I don't still think that too). Performances of his plays put me almost beside myself with intellectual excitement."

Shaw continued to write books and pamphlets on political and social issues. This included The Crime of Imprisonment (1922) and Intelligent Woman's Guide to Socialism (1928). Charlotte's support of her husband was vitally important to his career. As Stanley Weintraub has pointed out: "Childless, they indulged in surrogate sons and daughters whose children often went to school on quiet Shavian largess. Granville Barker and Lillah McCarthy had their Royal Court and Savoy seasons underwritten by G.B.S., who lost, unconcernedly, all his investment."

In 1928 Frank Harris wrote to Shaw asking if he could write his biography. Shaw replied: "Abstain from such a desperate enterprise... I will not have you write my life on any terms." Harris was convinced that the royalties of the proposed book would solve his financial problems. In 1929 he wrote: "You are honoured and famous and rich - I lie here crippled and condemned and poor."

Eventually, Shaw agreed to cooperate with Harris in order to help him provide for his wife. Shaw told a friend that he had to agree because "frank and Nellie... were in rather desperate circumstances." Shaw warned Harris: "The truth is I have a horror of biographers... If there is one expression in this book of yours that cannot be read at a confirmation class, you are lost for ever. "

Shaw sent Harris contradictory accounts of his life. He told Harris that he was "a born philanderer". On another occasion he attempted to explain why he had little experience of sexual relationships. In 1930 he wrote to Harris: "If you have any doubts as to my normal virility, dismiss them from your mind. I was not impotent; I was not sterile; I was not homosexual; and I was extremely susceptible, though not promiscuously."

Frank Harris died of heart failure on 26th August 1931. Shaw sent Nellie a cheque and she arranged to send him the galley-proofs. The book was then rewritten by Shaw: "I have had to fill in the prosaic facts in Frank's best style, and fit them to his comments as best I could; for I have most scrupulously preserved all his sallies at my expense.... You may, however, depend on it that the book is not any the worse for my doctoring." George Bernard Shaw was published in 1932.

During the Blitz, the Shaws, now in their middle eighties, moved out of London. Shaw was a strong opponent of Britain's involvement in the Second World War, which he described "fundamentally not merely maniacal but nonsensical". He wrote very little but he did find the energy to produce Everybody's Political What's What (1944).

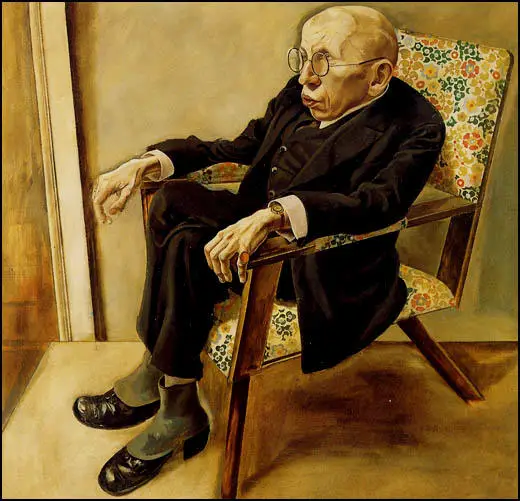

Max Beerbohm did over forty caricatures of George Bernard Shaw during his lifetime. He did not find Shaw's appearance attractive. He mentioned his pallid pitted skin and red hair like seaweed. "The back of his neck was especially bleak; very long, untenanted, and dead white". He admitted that Shaw's political views did not help: "My admiration for his genius has during fifty years and more been marred for me by dissent from almost any view that he holds about anything."

Charlotte Payne-Townshend Shaw, who had suffered from osteitis deformans for many years, died aged eighty-six on 12th September 1943. Shaw continued to write and his last play, Why She Would Not, was completed on 23rd July, 1950, three days before Shaw's ninety-fourth birthday.

George Bernard Shaw had a fall on 10th September 1950, while pruning trees. He was taken to hospital where it was discovered that he had fractured his hip. Bedridden, he developed kidney failure and died on 2nd November.

On this day in 1893 artist Georg Grosz, the son of a pub owner, was born in Berlin, Germany. He was brought up by devout Lutheran parents. His father was warden at the local masonic hall. "My father himself used sometimes to draw on the large cardboard sheets pinned to the square table... I can still remember sitting on his lap and watching all sorts of creatures come to life under his hand."

His father died in 1901 and the family moved to Berlin. "My mother and aunt sewed blouses for some big concern - hard work that brought in little cash. True, living was cheap, and we had enough of the bare necessities, but we were constantly beset by money worries now.... We were living in a real working-class district, though I did not realize it at the time."

Grosz was a talented artist and began attending a weekly drawing class taught by a local painter. In 1909 he became a student at the Dresden Academy of Fine Arts, where his teachers were Robert Sterl and Osmar Schindler. In 1911 he moved to the Berlin College of Arts and Crafts where he studied under Emil Orlik. During this period Grosz had his first caricatures published in the Berliner Tageblatt.

On the outbreak of the First World War Grosz was conscripted into the German Army. "What can I say about the First World War, a war in which I served as an infantryman, a war I hated at the start and to which I never warmed as it proceeded? I had grown up in a humanist atmosphere, and war to me was never anything but horror, mutilation and senseless destruction, and I knew that many great and wise people felt the same way about it. At the outbreak of hostilities, Germany was in the throes of a kind of mass delirium, but when the first flush of that was over there was nothing to take its place."

A strong opponent of the war, he was eventually released as unfit for duty. Grosz wrote to a friend "The time I spent in the stranglehold of militarism was a period of constant resistance - and I know there was not one thing I did which did not utterly disgust me... I have one dream: perhaps there will, after all, be changes, rebellions, perhaps one day international socialism which has lost its backbone will gather strength enough for an open uprising... It is an absurd dream, no more... to the slaughterhouse!"

However, the following year, desperate for soldiers, Grosz was called up again. Kept from frontline action, Grosz was used to transport and guard prisoners of war. "In 1916 I was discharged from military service, or rather, given a sort of leave of absence on the understanding that I might be recalled within a few months. And so I was a free man, at least for a while. The collapse of Germany was only a matter of time. All the fine phrases were now no more than stale, rank printer's in on brown substitute paper. I watched it all from my studio in Sudende, living and drawing in a world of my own. I drew soldiers without noses; war cripples with crab-like limbs of steel; two medical orderlies tying a violent infantryman up in a horse blanket; a one-armed soldier using his good hand to salute a heavily bemedalled lady who had just passed him a biscuit; a colonel, his fly wide open, embracing a nurse; a hospital orderly emptying a bucket full of pieces of human flesh down a pit."

Grosz hated the strong nationalism that had emerged during the war in Germany. Grosz's close friend, the artist, Helmut Herzfeld, shared this view and decided to change his name to John Heartfield in 1916 in "protest against German nationalistic fervour". Grosz decided to follow his example changed the spelling of his name to "de-Germanise" and internationalise his name – thus Georg became "George".

In the middle of 1917 Grosz was recalled to the German Army. "My new duties were to train recruits and to transport and guard prisoners of war. But I had enough and one night they found me semi-conscious, head-first in the latrine. I spent some time in hospitals after that. Whenever I had a moment to spare I would vent my spleen in sketches of everything about me that I hated, either in my notebook or on sheets of writing paper; the brutal faces of my comrades, badly mutilated war cripples, arrogant officers, lascivious nurses."

George Grosz had joined the Spartacus League, an anti-war organization, led by Karl Liebknecht and Rosa Luxemburg. He now considered himself a Marxist and a pacifist. He was terribly unhappy in the army and in 1917 he tried to commit suicide and Grosz was placed in an army hospital. According to Grosz, it was decided to execute him but he was saved by the intervention of one of his wealthy patrons, Count Harry Clemens Ulrich Kessler. Grosz was now diagnosed as suffering from shell-shock and was discharged from the German Army.

The war had a major impact on his art. Grosz joined with John Heartfield in protesting about the German wartime propaganda campaign against the allies. He was also totally opposed to the war continuing when it was clear that victory was impossible. His most powerful anti-war drawings during this period, was such Fit for Active Service (1918), in which a well-fed doctor inspecting a skeleton with an ear trumpet and pronouncing a skeleton, "KV" fit for duty. Unconcerned with the diagnosis, the surrounding officers appear either bored or absorbed in other matters.

The German government of Max von Baden asked President Woodrow Wilson for a cease-fire on 4th October, 1918. "It was made clear by both the Germans and Austrians that this was not a surrender, not even an offer of armistice terms, but an attempt to end the war without any preconditions that might be harmful to Germany or Austria." This was rejected and the fighting continued. On 6th October, it was announced that Karl Liebknecht, who was still in prison, demanded an end to the monarchy and the setting up of Soviets in Germany.

By the 8th November, workers councils took power in virtually every major town and city in Germany. This included Bremen, Cologne, Munich, Rostock, Leipzig, Dresden, Frankfurt, Stuttgart and Nuremberg. Theodor Wolff, writing in the Berliner Tageblatt: "News is coming in from all over the country of the progress of the revolution. All the people who made such a show of their loyalty to the Kaiser are lying low. Not one is moving a finger in defence of the monarchy. Everywhere soldiers are quitting the barracks."

On 7th November, 1918, Kurt Eisner, a member of the Independent Social Democratic Party (USPD) established a Socialist Republic in Bavaria. Several leading socialists arrived in the city to support the new regime. This included Erich Mühsam, Ernst Toller, Otto Neurath, Silvio Gesell and Ret Marut. Eisner also wrote to Gustav Landauer inviting him to Munich: "What I want from you is to advance the transformation of souls as a speaker." Landauer became a member of several councils established to both implement and protect the revolution.

Konrad Heiden wrote: "On November 6, 1918, he (Kurt Eisner) was virtually unknown, with no more than a few hundred supporters, more a literary than a political figure. He was a small man with a wild grey beard, a pince-nez, and an immense black hat. On November 7 he marched through the city of Munich with his few hundred men, occupied parliament and proclaimed the republic. As though by enchantment, the King, the princes, the generals, and Ministers scattered to all the winds."

George Grosz was a supporter of the German Revolution. Grosz was especially hostile to Friedrich Ebert, the leader of the German Social Democrat Party, and the leader of the government. "President Ebert had his beard trimmed, looked more and more like a managing director and changed his democratic felt hat for a shiny topper. Secretary of State Otto Meissner, the republic's master of ceremonies, made sure that he performed the office of his illustrious predecessors with due dignity and did not commit too many proletarian solecisms in the pursuit of his exalted duties."

The Spartacus League published a leaflet that claimed: "The Ebert-Scheidemann government intends, not only to get rid of the last representative of the revolutionary Berlin workers, but to establish a regime of coercion against the revolutionary workers." It is estimated that over 100,000 workers demonstrated against the sacking of Eichhorn the following Sunday in "order to show that the spirit of November is not yet beaten."

By 13th January, 1919 the rebellion had been crushed and most of its leaders were arrested. This included Rosa Luxemburg and Karl Liebknecht, who refused to flee the city, and were captured on 16th January and taken to the Freikorps headquarters. "After questioning, Liebknecht was taken from the building, knocked half conscious with a rifle butt and then driven to the Tiergarten where he was killed. Rosa was taken out shortly afterwards, her skull smashed in and then she too was driven off, shot through the head and thrown into the canal."

Friedrich Ebert, the president of Germany, arranged for 30,000 Freikorps, under the command of General Burghard von Oven, to take Munich. At Starnberg, some 30 km south-west of the city, they murdered 20 unarmed medical orderlies. The Red Army knew that the choice was armed resistance or being executed. The Bavarian Soviet Republic issued the following statement: "The White Guards have not yet conquered and are already heaping atrocity upon atrocity. They torture and execute prisoners. They kill the wounded. Don't make the hangmen's task easy. Sell your lives dearly."

George Grosz explained that the experience of war had a major impact on political consciousness: "Yes, everyone was now allowed his say. But having been used to taking their marching orders for years, all they could do was strut about a little less stiffly perhaps but also less smartly than before. The people obviously missed the sharp voice of command, and as for their vaunted freedom, they were at a complete loss what to do with it. Each one had a political view, compounded of fear, envy and hope - but what good were these views to anyone if no leader came forward to put them into practice? And as the people themselves refused to shoulder the responsibility or the blame, they had to look for a scapegoat. One was ready to hand: the Jew."

Zbyněk Zeman has pointed out in his book, Heckling Hitler: Caricatures of the Third Reich (1984) that Grosz's art was deeply influenced by the political situation: "The brutality and confusion of Germany after World War I were strikingly reflected in George Grosz's drawings. His drawing Communists Fall and Shares Rise refers to Bloody Week (10-17 January 1919) when regular and irregular troops of the Republic crushed the communist 'Spartacists', who had occupied the imperial palace in Berlin."

Uwe M. Schneede, the author of George Grosz: His Life and Work (1979) has pointed out that the drawing was inspired by a phrase used by Rosa Luxemburg during the First World War: "Grosz links military action against the workers with the economic interests of the ruling classes. These drawings are comments on the Marxist interpretation of history, made wholly convincing through the powerful characterisation of the facial expressions of those who order the murders and those who carry them out."

George Grosz began contributing work to Die Neue Jugend, an arts journal published by his brother. His work was influenced by his friend, John Heartfield who had "developed a new very amusing style of using collage and bold typography". Grosz helped him develop what became known as photomontage (the production of pictures by rearranging selected details of photographs to form a new and convincing unity). We... invented photomontage in my South End studio at five o'clock on a May morning in 1916, neither of us had any inkling of its great possibilities, nor of the thorny yet successful road it was to take. As so often happens in life, we had stumbled across a vein of gold without knowing it."

In 1920 George Grosz, John Heartfield and Raoul Hausmann organised the Erste Internationale Dada-Messe in the Berlin gallery owned by Otto Burchard. It was a comprehensive manifestation of Dada (a movement consisted of artists who rejected the logic, reason, and aestheticism of modern capitalist society, instead expressing nonsense, irrationality, and anti-bourgeois protest in their works). Among the 174 works in the exhibition were pictures by Grosz, Heartfield, Hausmann, Otto Dix, Max Ernst, Hannah Höch and Rudolf Schlichter. "The text on the panels accompanying each exhibit was partly Dadaist-polemical, partly political."

In 1922 Grosz traveled to the Soviet Union with the Danish writer Martin Andersen Nexø. Upon their arrival in Murmansk they were briefly arrested as spies; after their credentials were approved, they were allowed to meet with Lenin and other revolutionary leaders such as Grigory Zinoviev and Anatoly Lunacharsky. Grosz's six-month stay in the Soviet Union left him unimpressed by what he had seen. On his return he left the KPD, but he remained a committed socialist revolutionary. After spending time in the Soviet Union he could "no longer subscribe to the positive image of the happy, liberated worker".

George Grosz wrote in his autobiography about how the political situation had changed the role of the artist: “All moral codes were abandoned. A wave of vice, pornography and prostitution enveloped the whole country.... The streets became ravines of manslaughter and cocaine traffic, marked by steel rods and bloody, broken chair legs.” In 1923 he published the book, Ecce Homo. It contained 84 offset lithographs and 16 watercolor reproductions. "The book is a vicious satire of post-war German life, with politicians, capitalists, prostitutes, mutilated veterans, beggars, and drunks in various states of despair, lust, and rage. The German government banned it and Grosz was put on trial for public offense. While he was clearly influenced by the Cubist, Bauhaus, and Fauvist movements, in Ecce Homo, Grosz’s raw, angry style is distinctly his own."

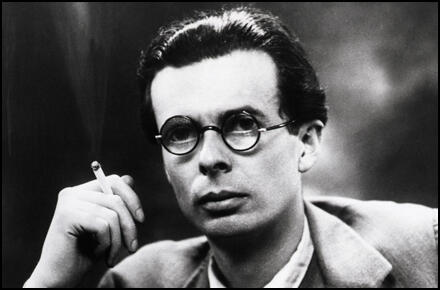

On this day in 1894 writer Aldous Huxley, the third son of Leonard Huxley, a teacher at Charterhouse School and subsequently editor of The Cornhill Magazine, was born in Godalming.

His mother, Julia Frances Huxley, was the daughter of Thomas Arnold (1823–1900) and the granddaughter of Thomas Arnold (1795–1842) of Rugby School. His grandfather was T. H. Huxley and his aunt was Mary Humphry Ward. His eldest brother was Julian Huxley.

Huxley attended Prior's Field, a progressive school founded by his mother. He arrived at Eton College in the autumn 1908. Soon afterwards his mother died that according to one biographer, destroyed his faith in life. In 1911 Huxley was struck down by a staphylococcic infection in the eye that left him purblind for eighteen months. According to David King Dunaway: "At home Huxley taught himself to read Braille, to touch-type, and to play the piano. His eyesight improved to one-quarter of normal vision in one eye (he spent half a century experimenting with alternative therapies and surgery)."

Huxley won a scholarship to Balliol College, to read English language and literature. However, he could only study by dilating his eyes with drops and using a large magnifying glass. While at Oxford University Huxley contributed articles to The Athenaeum. This brought him into contact with John Middleton Murry who introduced him to writers such as D. H. Lawrence and Katherine Mansfield.

Huxley began spending time with Philip Morrell and Ottoline Morrell at their home Garsington Manor near Oxford. It was also a refuge for conscientious objectors. They worked on the property's farm as a way of escaping prosecution. It also became a meeting place for a group of intellectuals described as the Bloomsbury Group. Members included Virginia Woolf, Vanessa Bell, Clive Bell, John Maynard Keynes, David Garnett, E. M. Forster, Duncan Grant, Lytton Strachey, Dora Carrington, Gerald Brenan, Ralph Partridge, Bertram Russell, Leonard Woolf, Desmond MacCarthy and Arthur Waley. Other people who Huxley met at Garsington included Dorothy Brett, Mark Gertler, Siegfried Sassoon, Goldsworthy Lowes Dickinson, Thomas Hardy, Vita Sackville-West, Harold Nicolson and T.S. Eliot.

One of the members of this group, Frances Partridge, later recalled in her autobiography, Memories (1981): "They were not a group, but a number of very different individuals, who shared certain attitudes to life, and happened to be friends or lovers. To say they were unconventional suggests deliberate flouting of rules; it was rather that they were quite uninterested in conventions, but passionately in ideas. Generally speaking they were left-wing, atheists, pacifists in the First World War, lovers of the arts and travel, avid readers, Francophiles. Apart from the various occupations such as writing, painting, economics, which they pursued with dedication, what they enjoyed most was talk - talk of every description, from the most abstract to the most hilariously ribald and profane."

Leonard Woolf first met Huxley at Garsington Manor. He later commented: "The Oxford generations of the nineteen tens and nineteen twenties produced a remarkable constellation of stars of the first magnitude and I much enjoyed seeing them twinkle in the Garsington garden. There for the first time I saw the young Aldous Huxley folding his long, grasshopper legs into a deckchair and listened entranced to a conversation which is unlike that of any other person that I have talked with. I could never grow tired of listening to the curious erudition, intense speculative curiosity, deep intelligence which, directed by a gentle wit and charming character, made conversation an art."

Aldous Huxley fell in love with Dora Carrington during this period. "Her short hair, clipped like a page's, hung in a bell of elastic gold about her cheeks. She had large blue china eyes, whose expression was one of ingenuous and often puzzled earnestness." Although she enjoyed his company she was not looking for a physical relationship with Huxley. He told Dorothy Brett: "Carrington and I had a long argument on the subject of virginity: I may say it was she who provoked it by saying that she intended to remain a vestal for the rest of her life. All expostulations on my part were in vain."

After obtaining a first at Oxford University, Huxley taught at Repton School and at Eton College, where among his students were George Orwell and Harold Acton. He also published four volumes of poetry: The Burning Wheel (1916), Jonah (1917), The Defeat of Youth (1918), and Leda (1920). Lytton Strachey liked Huxley's poetry but claimed that "he looked like a piece of seaweed" but he was "incredibly cultured."

Huxley married, Maria Nys, a Belgian refugee who he had met at Garsington Manor, on 10th July 1919. The following year she gave birth to a son, Matthew (April 1920). They lived in a small flat in Hampstead, and as well as contributing to literary journals he began work on his first novel, Crome Yellow (1921). Scott Fitzgerald wrote that the novel was "the highest point so far attained by Anglo-Saxon sophistication" and that Huxley was "the wittiest man now writing in English".

Crome Yellow brought Huxley instant fame but upset his friends who appeared in the novel. This included Dora Carrington (Mary Bracegirdle). In the novel Huxley recreated his many discussions with Carrington. She explained what she was looking for in a man: "It must be somebody intelligent, somebody with intellectual interests that I can share. And it must be somebody with a proper respect for women, somebody who's prepared to talk seriously about his work and his ideas and about my work and my ideas. It isn't, as you see, at all easy to find the right person."

Ottoline Morrell felt betrayed by Huxley for writing about her in Crome Yellow. The character, Priscilla Wimbush, was described as having a "large square middle-aged face, with a massive projecting nose and little greenish eyes, the whole surmounted by a lofty and elaborate coiffure of a curiously improbable shade of orange." Ottoline was also furious about his rude and unfunny descriptions of her friends, Dorothy Brett, Dora Carrington, Bertram Russell and Mark Gertler. She told Huxley that his book reminded her of "poor photography".

Huxley followed Crome Yellow with Antic Hay (1923) and Those Barren Leaves (1925). According to David King Dunaway, all three novels "satirized social behaviour in post-war Britain using friends and family as fodder for incisive characterizations... The comic lightness of the novels was undermined by much wider social concerns.... Moreover, a dark thread runs through Huxley's musings on corruption in the smart set; his characters are torn between pleasures of the flesh and an austere dedication to the spirit, and Huxley was willing to expose human frailty, to illuminate hypocrisy."

Huxley continued the idea of writing about people he knew in his next novel, Point Counter Point (1928). Characters in this novel included Lucy Tantamount (Nancy Cunard), John Bidlake (Augustus John), Everard Webley (Oswald Mosley), Mark Rampion (D. H. Lawrence), Mary Rampion (Frieda Lawrence), Denis Burlap (John Middleton Murry) and Beatrice Gilray (Katherine Mansfield).

Beatrice Webb praised the writing of Huxley but disliked the subject matter of his books. She put in him the same group as D. H. Lawrence, Compton MacKenzie, David Garnett and Norman Douglas: "clever novelists... all depicting men and women as mere animals, and morbid at that. except always that these bipeds practise birth control and commit suicide. so it looks as if the species would happily die out. it is an ugly and tiresome idol of the mind, but it lends itself to a certain type of fantastic wit and stylish irony.

Huxley's books sold very well and with his royalties he purchased a villa in Bandol on the south coast of France. He also had a summer home at Forte dei Marmi in Tuscany. After the death of his friend, D. H. Lawrence, Huxley arranged for the publication of The Letters of D. H. Lawrence (1932). As well as novels, plays and short stories, Huxley wrote a large number of articles for newspapers and magazines.

In summer 1932 Huxley published Brave New World. It was an international best-seller and established him as Britain's best-known novelist between the wars. Translated into twenty-eight languages, the novel was inspired by Men Like Gods, a utopian novel by H. G. Wells. However, George Orwell argued that the novel "must be partly derived from" We by the Russian writer, Yevgeny Zamyatin. Huxley denied that he had ever heard of this book.

David King Dunaway has pointed out: "The novel, the first about human cloning, is a dystopia set five centuries in the future, when overpopulation has led to biogenetic engineering. Through computerized genetic selection, social engineers create a population happy with its lot. All the earth's children are born in hatcheries, and Soma, a get-happy pill, irons out most problems."

Time Magazine saw it as an attack on the culture of the United States with Henry Ford as the new God (worshippers say "Our Ford" instead of "Our Lord"): "Huxley's 1932 work - about a drugged, dull and mass-produced society of the future - has been challenged for its themes of sexuality, drugs and suicide. The book parodies H.G. Wells' utopian novel Men Like Gods and expresses Huxley's disdain for the youth and market-driven culture of the U.S. Chewing gum, then as now a symbol of America's teenybopper shoppers, appears in the book as a way to deliver sex hormones and subdue anxious adults; pornographic films called feelies are also popular grown-up pacifiers."

Beatrice Webb was also highly critical of the book: "I have been reading Aldous Huxley's Point Counter Point, and pondering over this strangely pathological writing, pathological without knowing it. The febrile futility of the particular clique he describes reminds me of that far more powerful book The Magic Mountain, by Thomas Mann. Far more powerful because Mann is describing a society of sick people ... Huxley's group do not know that they are sick and are presented as a sample of normal human life. What with their continuous and promiscuous copulations, their shallow talk and chronic idleness, the impression left is one of simple disgust at their bodies and minds.... And the book, apart from arousing a morbid interest in morbidity, is dull, dull, dull. In a few years' time it will be unreadable - it represents a fashion. In this characteristic of fashionableness Aldous Huxley is like his maternal aunt, Mrs Humphry Ward; also in his tendency to preach."

Aldous Huxley's next novel was Eyeless in Gaza (1936). Huxley then suffered from "writer's block" and it was several years before he could complete another novel. In 1937 Aldous and Maria Huxley travelled to North America, spending time in New York City and San Cristobal, where he finished, Ends and Means (1937), a book explaining his pacifist beliefs.

In January 1938 the Huxleys moved to California and was employed by Hollywood film studios. He wrote the screenplays for Pride and Prejudice (1940), Madame Curie (1943), Jane Eyre (1943), A Woman's Vengeance (1948), Prelude to Fame (1950) and Alice in Wonderland (1951). He found working with studio executives difficult who he described as having "the characteristics of the minds of chimpanzees".

Huxley's next book, The Devils of Loudun (1952), was "a historical recreation of a story of demonically possessed French nuns and exorcists". Based on the true events in the small French town of Loudun in 1631, it features the activities of Father Urbain Grandier. As Time Magazine pointed out: "In The Devils of Loudun, Aldous Huxley with skill and scholarship resurrects one of the forgotten scandals of Christendom. The result is a brilliantly quarrelsome tract that is also one of the most fascinating historical narratives of the year."

Maria Huxley developed cancer. She told her friend: "To me, dying is no more than going from one room to another." She died on 12th February 1955. The following year he married Laura Archer (1911–2007), an Italian violinist, writer, and psychotherapist. He published his last novel, Island in 1962. He claimed "this is what Brave New World should have been, and wasn't".

Aldous Huxley died in Los Angeles, on 22nd November 1963, the same day that John F. Kennedy was assassinated.

On this day in 1913 an estimated 50,000 women reached Hyde Park at the end of the Women's Pilgrimage. In 1913 the National Union of Women Suffrage Societies (NUWSS) had nearly had 100,000 members. Katherine Harley, a senior figure in the NUWSS, suggested holding a "Woman's Suffrage Pilgrimage" in order to show Parliament how many women wanted the vote. According to Lisa Tickner, the author of The Spectacle of Women (1987) argued: "A pilgrimage refused the thrill attendant on women's militancy, no matter how strongly the militancy was denounced, but it also refused the glamour of an orchestrated spectacle."

Members of the NUWSS set off on 18th June, 1913. The North-Eastern Federation, the North and East Ridings Federation, the West Riding Federation, the East Midland Federation and the Eastern Counties Federation, travelled the Newcastle-upon-Tyne to London route. The North-Western Federation, the Manchester and District, the West Lancashire, West Cheshire and North Wales Federation, the West Midlands Federation, and the Oxfordshire, Berkshire, Buckinghamshire and Bedfordshire Federation travelled on the Carlisle to the capital route. The South-Western Federation, the West of England Federation, the Surrey, Sussex and Hampshire Federation walked from Lands End to Hyde Park.

As Elizabeth Crawford, the author of The Suffragette Movement (1999), pointed out: "Pilgrims were urged to wear a uniform, a concept always close to Katherine Harley's heart. It was suggested that pilgrims should wear white, grey, black, or navy blue coats and skirts or dresses. Blouses were either to match the skirt or to be white. Hats were to be simple, and only black, white, grey, or navy blue. For 3d, headquarters supplied a compulsory raffia badge, a cockle shell, the traditional symbol of pilgrimage, to be worn pinned to the hat. Also available were a red, white and green shoulder sash, a haversack, made of bright red waterproof cloth edged with green with white lettering spelling out the route travelled, and umbrellas in green or white, or red cotton covers to co-ordinate civilian umbrellas."

Members of the NUWSS publicized the Women's Pilgrimage in local newspapers. Helen Hoare, for example, sent a letter to The East Grinstead Observer: "It is no doubt true that some men were formerly inclined to support it have been alienated by the doings of the militant party. The National Union of Women’s Suffrage Society (that is the law-abiding, non-militant party), in order to show the world that it is alive, and to encourage its members in a long and disheartening struggle, has organised a great pilgrimage from all parts of England to London."

Lisa Tickner has pointed out: "Most women travelled on foot, though some rode horses or bicycles, and wealthy sympathisers lent cars, carriages, or pony traps for the luggage. The intention was not that each individual should cover the whole route but that the federations would do so collectively." One of the marchers, Margory Lees, claimed that the pilgrimage succeeded in "visiting the people of this country in their own homes and villages, to explain to them the real meaning of the movement." Another participant, Margaret Greg, recorded: "My verdict on the Pilgrimage is that it is going to do a very great deal of work - the sort of work that has hitherto only been done by towns or at election times is being spread all over the country." The pilgrims were accompanied by a lorry, containing their baggage. Margaret Ashton brought her car and picked up those suffering from exhaustion.

During the next six weeks held a series of meetings all over Britain where they sold The Common Cause and other NUWSS literature. The meetings held on the way were nearly all peaceful. However, the women had to endure a great deal of abuse. Harriet Blessley of Portsmouth recalled: "It is difficult to feel a holy pilgrim when one is called a brazen hussy."

A serious riot took place at a meeting organised by Marie Corbett of the East Grinstead Suffrage Society and Edward Steer of the Men's League for Women's Suffrage at East Grinstead three days before the end of the march. As the The East Grinstead Observer reported: "The procession was not an imposing one. It consisted of about ten ladies who were members of the Suffrage Society. Mrs. Marie Corbett led the way carrying a silken banner bearing the arms of East Grinstead. The reception, which the little band of ladies got, was no means friendly. Yells and hooting greeted them throughout most of the entire march, and they were the targets for occasional pieces of turf, especially when they passed through Queen’s Road. In the High Street they found a crowd of about 1,500 people awaiting them."

Edward Steer was the chairman and Laurence Housman was the main speaker. The local newspaper reported that both men were attacked by the crowd: "By this time pieces of turf and a few ripe tomatoes and highly seasoned eggs were flying about, and were not always received by the person they were intended for. The unsavoury odur of eggs was noticeable over a considerable area. Unhappily, Miss Helen Hoare of Charlwood Farm, was struck in the face with a missile and received a cut on the cheek and was taken away for treatment."

Despite this riot The Common Cause reported that overall the pilgrimage was a great success and "the result was nothing less than a revelation, to those who doubted it, of the almost universal sympathy given to the Non-militant Suffrage Cause once it is understood." The Daily News commented on the woman's brown skins on the march and added "never was so peaceful, so pleasant a raid of London - and rarely one more picturesque or more inspiring."

An estimated 50,000 women reached Hyde Park in London on 26th July. As The Times newspaper pointed out, the march was part of a campaign against the violent methods being used by the Women Social & Political Union: "On Saturday the pilgrimage of the law abiding advocates of votes for women ended in a great gathering in Hyde Park attended by some 50,000 persons. The proceedings were quite orderly and devoid of any untoward incident. The proceedings, indeed, were as much a demonstration against militancy as one in favour of women's suffrage. Many bitter things were said of the militant women."

On 29th July 1913, Millicent Fawcett wrote to Herbert Asquith "on behalf of the immense meetings which assembled in Hyde Park on Saturday and voted with practical unanimity in favour of a Government measure." Asquith replied that the demonstration had "a special claim" on his consideration and stood "upon another footing from similar demands proceeding from other quarters where a different method and spirit is predominant."

On this day in 1917 Florence Farmborough writes in her diary about Yasha Bochkareva, the founder of the Women's Death Battalion.

Yasha Bachkarova, a Siberian woman soldier had served in the Russian Army since 1915 side by side with her husband; when he had been killed, she continued to fight. She had been wounded twice and three times decorated for valour. When she knew the soldiers were deserting in large numbers, she made her way to Moscow and Petrograd to start recruiting for a Woman's Battalion. It is reported that she had said, "If the men refuse to fight for their country, we will show them what the women can do!" So this woman warrior, Yasha Bachkarova, began her campaign; it was said that it had met with singular success. Young women, some of aristocratic families, rallied to her side; they were given rifles and uniforms and drilled and marched vigorously. We Sisters were of course thrilled to the core.

9th August, 1917: Last Monday, an ambulance-van drove up with three wounded women soldiers. We were told that they belonged to the Bachkarova Women's Death Battalion. We had not heard the full name before, but we instantly guessed that it was the small army of women recruited in Russia by the Siberian women soldier, Yasha Bachkarova. Naturally we were all very impatient to have news of this remarkable battalion, but the women were sadly shocked and we refrained from questioning them until they had rested. The van driver was not very helpful but he did know that the battalion had been cut up by the enemy and had retreated.

13th August, 1917: At dinner we heard more of the Women's Death Battalion. It was true; Bachkarova had brought her small battalion down south of the Austrian Front, and they had manned part of the trenches which had been abandoned by the Russian Infantry. The size of the Battalion had considerably decreased since the first weeks of recruitment, when some 2000 women and girls had rallied to the call of their leader. Many of them, painted and powdered, had joined the Battalion as an exciting and romantic adventure; she loudly condemned their behaviour and demanded iron discipline. Gradually the patriotic enthusiasm had spent itself; the 2000 slowly dwindled to 250. In honour to those women volunteers, it was recorded that they did go into the attack; they did go "over the top". But not all of them. Some remained in the trenches, fainting and hysterical; others ran or crawled back to the rear.

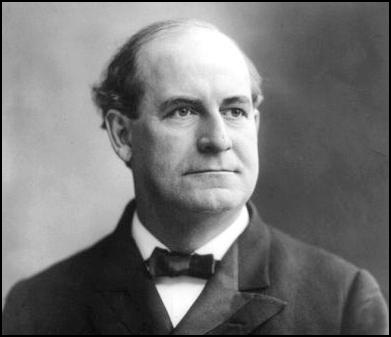

On this day in 1925 American politician William Jennings Bryan died.

William Jennings Bryan, the son of Silas Lillard Bryan and Mariah Elizabeth Jennings, was born in Salem, Illinois, on 19th March, 1860. Bryan graduated from Illinois College in 1881 and afterwards studied law in Chicago at the Northwestern University School of Law.

Bryan married Mary Elizabeth Baird, a fellow law student, on 1st October, 1884. He practiced law in Jacksonville but in 1887 moved to the fast-growing Lincoln in Lancaster County. Bryan was an active member of the Democratic Party and in 1890 was elected to the U.S. House of Representatives. He was only the second Democrat to be elected to Congress in the history of Nebraska.

Bryan soon established himself as one of the nation's leading orators. A Democratic with progressive views, he supported campaigns for graduated income tax, regulating child labour and women's suffrage. After his defeat 1894 he was appointed editor of the Omaha World Herald before becoming the Democratic presidential candidate in 1896. At the age of 36 he was the youngest man ever to win the nomination.

During the campaign Bryan became the first presidential candidate to use a car. His Republican opponent, William McKinley argued for high protective tariffs on foreign goods. This message was popular with America's leading industrialists and with the support of Mark Hanna, McKinley was able to raise $3,500,000 for his campaign. Outspending Bryan by 20 to 1, McKinley easily defeated his opponent by an electoral vote of 271 to 176.

Bryan was also the Democratic Party candidate in 1900. A devout anti-imperialist he urged a non-aggressive foreign policy. In one speech he argued: "The nation is of age and it can do what it pleases; it can spurn the traditions of the past; it can repudiate the principles upon which the nation rests; it can employ force instead of reason; it can substitute might for right; it can conquer weaker people; it can exploit their lands, appropriate their property and kill their people; but it cannot repeal the moral law or escape the punishment decreed for the violation of human rights." He added: "Behold a republic standing erect while empires all around are bowed beneath the weight of their own armaments - a republic whose flag is loved while other flags are only feared." This policy was not popular with the American public and this time he was defeated by McKinley by 292 electoral votes to 155.

Bryan became editor of his own newspaper, The Commoner . However, his main source of income was as a public speaker. Over the next few years he toured America giving talks on current affairs. He argued: "Never be afraid to stand with the minority when the minority is right, for the minority which is right will one day be the majority." He usually charged $500 per speech in addition to a percentage of the profits. He invested some of this money in buying large areas of land in Nebraska and Texas.

Bryan was again selected as the Democratic candidate for the 1908 Presidential Election and John W. Kern, a progressive politician from Indiana, became his running mate. The Republican Party selected Theodore Roosevelt and William Howard Taft. Using the slogan: "Shall the People Rule?", Bryan campaigned in favour of new income and inheritance taxes. He also warned against the growing influence of corporations in elections and called for their donations to political parties to become public. Bryan went down to his largest defeat, winning only 162 electoral votes to Roosevelt's 321.

Bryan returned to the lecture circuit where he continued to advocate progressive policies. This included arguing that religion was the foundation of morality, and individual and group morality was the foundation for peace and equality. However, in other ways he was a traditionalist and began attacking the ideas of Charles Darwin. He told one audience: "The parents have a right to say that no teacher paid by their money shall rob their children of faith in God and send them back to their homes skeptical, or infidels, or agnostics, or atheists." On another occasion he argued: "If we have to give up either religion or education, we should give up education."

In 1905 he suggested that "the Darwinian theory represents man reaching his present perfection by the operation of the law of hate, the merciless law by which the strong crowd out and kill off the weak. If this is the law of our development then, if there is any logic that can bind the human mind, we shall turn backward to the beast in proportion as we substitute the law of love. I choose to believe that love rather than hatred is the law of development."

In 1912 Theodore Roosevelt stood as the Progressive Party candidate against William H. Taft. This split the traditional Republican vote and enabled Woodrow Wilson, the Democratic Party candidate, to be elected. Wilson appointed Bryan as secretary of state. A passionate pacifist, Bryan convinced 31 nations to agree in principle to his proposal to accept a year's cooling-off period during political conflicts, allowing the dispute to be studied by an international commission. Bryan resigned from the government in protest against the way that President Wilson dealt with the sinking of the Lusitania. However, when the United States entered the First World War in 1917, Bryan gave his full support to the war effort.

As Bryan got older he became more conservative in his political attitudes. In June, 1924, the journalist, Heywood Broun, accused Bryan of being a supporter of the Ku Klux Klan. "For William Jennings Bryan is the very type and symbol of the spirit of the Ku Klux Klan. He has never lived in a land of men and women. To him this country has been from the beginning peopled by believers and heretics. According to his faith mankind is base and cursed. Human reason is a snare, and so Bryan has made oratory the weapon of his aggressions. When professors in precarious jobs have disagreed with him about evolution, Mr. Bryan has never argued the issue, but instead has turned bully and burned fiery crosses at their doors." Broun also criticised Bryan for not opposing Jim Crow laws.

In the early 1920s Bryan began a campaign to bring an end to the teaching of evolution in schools. Bryan argued in 1922: " Now that the legislatures of the various states are in session, I beg to call attention of the legislators to a much needed reform, viz., the elimination of the teaching of atheism and agnosticism from schools, colleges and universities supported by taxation. Under the pretense of teaching science, instructors who draw their salaries from the public treasury are undermining the religious faith of students by substituting belief in Darwinism for belief in the Bible. Our Constitution very properly prohibits the teaching of religion at public expense. The Christian church is divided into many sects, Protestant and Catholic, and it is contrary to the spirit of our institutions, as well as to the written law, to use money raised by taxation for the propagation of sects. In many states they have gone so far as to eliminate the reading of the Bible, although its morals and literature have a value entirely distinct from the religious interpretations variously placed upon the Bible."

Tennessee governor Austin Peay, agreed with Bryan and in 1925 he passed what became known as the Butler Act. This prohibited public school teachers from denying the Biblical account of man's origin. The law also prevented the teaching of the evolution of man from what it referred to as lower orders of animals in place of the Biblical account.

The American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) announced that it would finance a test case challenging the constitutionality of this measure. John Thomas Scopes, a teacher at Rhea County High School in Dayton, Tennessee, was approached by engineer and geologist George Rappleyea, and asked if he would be willing to teach evolution at the Rhea County High School. Scopes agreed and was arrested on 5th May, 1925. America's most famous criminal lawyer, Clarence Darrow, offered to defend Scopes without a fee. Bryan agreed to help the prosecution by Arthur Thomas Stewart, the District Attorney. He was financed by the World Christian Fundamental Association.

The Scopes Trial began in Dayton on 11th July, 1925. Over 100 journalists arrived in the town to report on the trial. The Chicago Tribune installed its own radio transmitter and it became the first trial in American history to be broadcast to the nation. Three schoolboys testified that they had been present when Scopes had taught evolution in their school. When the judge, John T. Raulston, refused to allow scientists to testify on the truth of evolution, Clarence Darrow called William Jennings Bryan to the witness stand. This became the highlight of the 11 day trial and many independent observers believed that Darrow successfully exposed the flaws in Bryan's arguments during the cross-examination.

In his closing speech Bryan pointed out: "Let us now separate the issues from the misrepresentations, intentional or unintentional, that have obscured both the letter and the purpose of the law. This is not an interference with freedom of conscience. A teacher can think as he pleases and worship God as he likes, or refuse to worship God at all. He can believe in the Bible or discard it; he can accept Christ or reject Him. This law places no obligations or restraints upon him. And so with freedom of speech, he can, so long as he acts as an individual, say anything he likes on any subject. This law does not violate any rights guaranteed by any Constitution to any individual. It deals with the defendant, not as an individual, but as an employee, official or public servant, paid by the State, and therefore under instructions from the State.... It need hardly be added that this law did not have its origin in bigotry. It is not trying to force any form of religion on anybody. The majority is not trying to establish a religion or to teach it - it is trying to protect itself from the effort of an insolent minority to force irrellgion upon the children under the guise of teaching science."

Bryan went on to argue: "Evolution is not truth; it is merely a hypothesis - it is millions of guesses strung together. It had not been proven in the days of Darwin - he expressed astonishment that with two or three million species it had been impossible to trace any species to any other species - it had not been proven in the days of Huxley, and it has not been proven up to today. It is less than four years ago that Professor Bateson came all the way from London to Canada to tell the American scientists that every effort to trace one species to another had failed - every one. He said he still had faith in evolution but had doubts about the origin of species. But of what value is evolution if it cannot explain the origin of species? While many scientists accept evolution as if it were a fact, they all admit, when questioned, that no explanation has been found as to how one species developed into another."

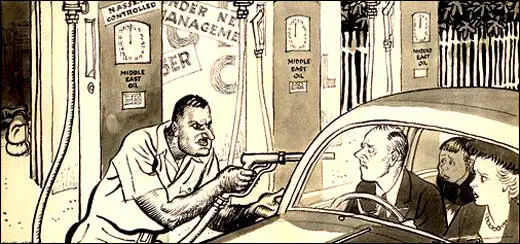

On this day in 1956 Gamal Abdel Nasser announces the nationalization of the Suez Canal. President Dwight Eisenhower became concerned about the close relationship developing between Egypt and the Soviet Union. In July 1956, Eisenhower cancelled a promised grant of 56 million dollars towards the building of the Aswan Dam. Nasser was furious and on 26th July he announced he intended to nationalize the Suez Canal. The shareowners, the majority of whom were from Britain and France, were promised compensation. Nasser argued that the revenues from the Suez Canal would help to finance the Aswan Dam.

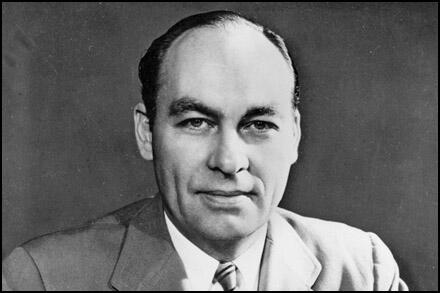

Anthony Eden replaced Winston Churchill as prime minister in April, 1955. Eden believed that he should take an early opportunity of seeking a fresh mandate from the electorate, and nine days after becoming prime minister he announced a general election for 26th May. At the time the Conservative Party was only 4% ahead of the Labour Party. During the 1955 General Election Eden emphasized the theme of the "property-owning democracy", and won by sixty seats. It was the first-time since 1900 that an incumbent administration had increased its majority in the House of Commons.

The Labour leader, Clement Attlee, retired and was replaced by the much younger, Hugh Gaitskell. It has been argued that when Hugh Gaitskell became leader in December, 1955, "British politics moved into a new era. Press criticisms became less inhibited. To some extent, Churchill and Attlee had been above criticism, but both Eden and, eventually, Gaitskell were fair game for a new breed of journalist." Eden found criticism difficult to take and William Clark, his press secretary, was kept very busy issuing statements defending his policies.

President Dwight Eisenhower became concerned about the close relationship developing between Egypt and the Soviet Union. In July 1956 Eisenhower cancelled a promised grant of 56 million dollars towards the building of the Aswan Dam. Gamal Abdel Nasser was furious and on 26th July he announced he intended to nationalize the Suez Canal. The shareowners, the majority of whom were from Britain and France, were promised compensation. Nasser argued that the revenues from the Suez Canal would help to finance the Aswan Dam.

Eden wrote to President Dwight Eisenhower for support: "In the light of our long friendship, I will not conceal from you that the present situation causes me the deepest concern. I was grateful to you for sending Foster over and for his help. It has enabled us to reach firm and rapid conclusions and to display to Nasser and to the world the spectacle of a united front between our two countries and the French. We have however gone to the very limits of the concessions which we can make.... I have never thought Nasser a Hitler, he has no warlike people behind him. But the parallel with Mussolini is close. Neither of us can forget the lives and treasure he cost before he was finally dealt with. The removal of Nasser and the installation in Egypt of a regime less hostile to the West, must therefore also rank high among our objectives. You know us better than anyone, and so I need not tell you that our people here are neither excited nor eager to use force. They are, however, grimly determined that Nasser shall not get away with it this time because they are convinced that if he does their existence will be at his mercy. So am I."

According to Harold Wilson, a Labour Party MP, Harold Macmillan, the Foreign Secretary was the main supporter of taking action against Nasser: "Eden was at first a reluctant warrior. Macmillan was putting the heat on from the start. At a separate dinner, he and Lord Salisbury were entertaining Robert Murphy, the US Defence Secretary. Macmillan took an extremely tough line about Nasser's action, which, he later explained, was designed to stiffen the American administration. Murphy was left to draw the conclusion that Britain would certainly go to war to secure the Canal and ensure free passage for the world's ships. In the whole history of the Suez fiasco, nothing has become clearer than the effect of Macmillan's tough line with Murphy both then and throughout the following weeks, when Eden was going through the torment of preparing to use force to recapture the Canal."

At a cabinet meeting in July the minutes recorded: "The Cabinet agreed that we should be on weak ground in basing our resistance on the narrow argument that Colonel Nasser had acted illegally. The Suez Canal Company was registered as an Egyptian company under Egyptian law; and Colonel Nasser had indicated that he intended to compensate the shareholders at ruling market prices. From a narrow legal point of view, his action amounted to no more than a decision to buy out the shareholders. Our case must be presented on wider international grounds. Our argument must be that the Canal was an important international asset and facility, and that Egypt could not be allowed to exploit it for a purely internal purpose. The Egyptians had not the technical ability to manage it effectively; and their recent behaviour gave no confidence that they would recognize their international obligations in respect of it. It was a piece of Egyptian property but an international asset of the highest importance and should be managed as an international trust. The Cabinet agreed that for these reasons every effort must be made to restore effective international control over the Canal. It was evident that the Egyptians would not yield to economic pressures alone. They must be subjected to the maximum political pressure which could only be applied by the maritime and trading nations whose interests were most directly affected. And, in the last resort, this political pressure must be backed by the threat - and, if need be, the use of force."

Walter Monckton, Eden's Minister of Defence, was the only cabinet minister to oppose this policy but decided against resigning: "I have remained in the Cabinet without resignation because I have not thought it right to take a step which I was assured would bring the Government down. The view which I have always expressed has been against the armed intervention which has taken place on the grounds - (a) that we should have half our own country and 90 per cent of world opinion against us; (b) that it was difficult to justify intervention on behalf of the invader and against the country invaded; (c) that it would inflame opinion against us in the Middle East and upset the whole of the Arab world; (d) that it would jeopardise our relations with the US which were the foundation of our international and defence policy."

Hugh Gaitskell, the leader of the Labour Party, warned Eden of the consequences of using military force: "Lest there should be any doubt in your mind about my personal attitude, let me say that I could not regard an armed attack on Egypt by ourselves and the French as justified by anything which Nasser has done so far or as consistent with the Charter of the United Nations. Nor, in my opinion, would such an attack be justified in order to impose a system of international control over the canal – desirable though this is. If, of course, the whole matter were to be taken to the United Nations and if Egypt were to be condemned by them as aggressors, then, of course, the position would be different. And if further action which amounted to obvious aggression by Egypt were taken by Nasser, then again it would be different. So far what Nasser has done amounts to a threat, a grave threat to us and to others, which certainly cannot be ignored; but it is only a threat, not in my opinion justifying retaliation by war."

Eden feared that Nasser intended to form an Arab Alliance that would cut off oil supplies to Europe. Secret negotiations took place between Britain, France and Israel and it was agreed to make a joint attack on Egypt. On 29th October 1956, the Israeli Army invaded Egypt. Two days later British and French bombed Egyptian airfields. British and French troops landed at Port Said at the northern end of the Suez Canal on 5th November. By this time the Israelis had captured the Sinai peninsula.

According to some historians, the majority of British people were on Eden's side. On 10 and 11 November an opinion poll found 53% supported the war, with 32% opposed (16) The majority of Conservative constituency associations passed resolutions of support of Eden. The British historian Barry Turner wrote that: "The public reaction to press comment highlighted the divisions within the country. But there was no doubt that Eden still commanded strong support from a sizeable minority, maybe even a majority, of voters who thought that it was about time that the upset Arabs should be taught a lesson. The Observer and Guardian lost readers; so too did the News Chronicle, a liberal newspaper that was soon to fold as a result of falling circulation."