On this day on 20th December

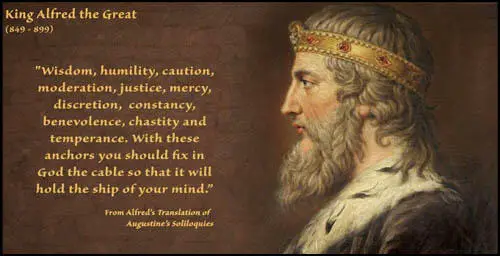

On this day in 899 Alfred the Great died. Alfred, the youngest son of King Ethelwulf of Wessex and Osburh, was born at Wantage, in about 848. He had a sister, Ethelswith and three brothers, Ethelbald, Ethelberht and Ethelred, who survived childhood. Alfred's grandfather, King Egbert, was the founder of the Wessex supremacy in 802 and ruled for over 40 years.

Alfred experienced poor health as a child. According to John Assler he had these problems "from the first flowering of his youth" and it was feared that he would die before reaching adulthood. A doctor who has studied his symptoms has suggested that he was suffering from tuberculosis or/and Crohn's disease.

In 856 Ethelwulf visited Rome for the first time. Alfred went with him and he left two of his sons, Ethelbald and Ethelberht to rule Wessex while he was away. Ethelbald became very angry when he heard that his father had married Judith of Flanders, the daughter of Charles the Bald, the king of Italy. Ethelbald was concerned that she might "produce heirs more throne-worthy than he".

Ethelwulf died eleven months after his return from Italy. Ethelbald now became king of Wessex. He also married his father's young widow, Judith. This caused a great scandal as this was forbidden by the Church. Ethelbald only survived his father by only a little over three years and died on 20th December 860. John Assler described Ethelbald as "iniquitous and grasping", and his reign as "two and a half lawless years".

Ethelberht replaced his brother as king. As well as Wessex he also became king of Kent. During this period Alfred lived at East Dene and according to one biographer, spent a good deal of time in Alfriston. The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle describes his reign as one of good harmony and great peace. Although this was true of internal affairs, the Vikings remained a threat, unsuccessfully storming Winchester and ravaging all eastern Kent. Ethelberht died in the autumn of 865 and was buried at Sherborne beside his brother Ethelbald.

Ethelred, who was only aged eighteen, became the next king of Wessex. In 868 Alfred married Ealhswith, daughter of a Mercian nobleman. They had five or six children together, including Edward the Elder, Ethelweard, Ethelflaed (who married Ethelred, the ruler of Mercia) and Elfthryth (who married Baldwin II the Count of Flanders).

The Vikings increased their attacks on England and over the next five years they conquered and installed their own rulers over Northumbria and East Anglia. They also captured Nottingham in Mercia. In 870 they turned their attention to Wessex and set up base at Reading. Alfred joined his brother in battle against the Vikings. A victory at Ashdown was followed by defeat at Basing.

Ethelred was badly wounded in battle and died of his injuries on 15th April, 871. Alfred was now the king of Wessex. "Never before and never since in our history have four brothers succeeded each other on the same throne, and all inside ten years. Ethelbald, Ethelberht and Ethelred were not slain in battle, although they all fought battles, but it is very possible that wounds in battle played their part in cutting short their lives."

Alfred faced a serious military crisis. The kingdoms of Northumbria, East Anglia and Mercia had all recently fallen to the Vikings. Wessex under Alfred was the only surviving Anglo-Saxon province. As Barbara Yorke has pointed out: "Alfred promoted himself as the defender of all Christian Anglo-Saxons against the pagan Viking threat and began the liberation of neighbouring areas from Viking control. He thus paved the way for the future unity of England."

Alfred was faced with a serious threat from Scandinavian leaders that included Ivar the Boneless, Björn Ironside, Halfdan Ragnarsson and Sigurd Snake-in-the-Eye. The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle records that these warriors had settled in Northumbria, Mercia and East Anglia. There is also evidence for a Danish and Norwegian presence in Yorkshire and the Lake District. Scandinavians took their paganism seriously, and destroyed a large number of churches in England.

The Vikings had developed new methods of war. The moved fast at sea in their long, many-oared ships carrying up to 100 men apiece, and on the land by rounding up all the horses where ever they touched and turning themselves into the first mounted infantry. They also learnt to build strong, stockaded forts, and when defeated retired behind these and were able to resist attacks from the British tribes.

Guthrum, a Danish chieftain, became a serious problem for Alfred with his army raiding Wessex. Alfred confronted him in a series of skirmishes but Guthrum's hopes of conquering all of Wessex came to an end with the Battle of Edington in May 878. The Danes were pursued to Chippenham and was besieged for ten days, until agreeing to surrender. Under the Treaty of Wedmore the borders dividing the lands of Alfred and Guthrum were established.

To show his good will, Guthrum converted to Christianity and took on the Christian name Ethelstan with Alfred as his godfather. (18) As the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle pointed out: "Then the raiding army granted him (Alfred) hostages and great oaths that they would leave his kingdom and also promised him that their king (Guthrum) would receive baptism; and they fulfilled it. And three weeks later the king Guthrum came to him, one of thirty of the most honourable men who were in the raiding army, at Aller - and that is near Athelney - and the king received him at baptism; and his chrism loosing was at Wedmore."

Guthrum upheld his end of the treaty and left Alfred's territory unmolested. According to Douglas Woodruff, the author of Alfred the Great (1974) argued: "Alfred himself, the respect the Danes could not withhold from him as a fighting man, the magnanimity of his spirit, and his deep personal conviction of the truths of Christianity, which made a lasting impression on Guthrum, putting him in a class apart from the other Danish leaders. He kept his pact with Alfred, and it was no doubt by agreement that after a year at Cirencester he moved his army into East Anglia, and began settling them on the land."

Alfred also took control of Mercia, including London, its capital, in 886. Some of his charters now called him "king of the Anglo-Saxons". Assler described Alfred as "ruler of all Christians of the island of Britain" and the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle asserts of Alfred that all the people "except what was under subjection to the Danes submitted to him". David Pratt points out that although almost all chroniclers agree that the Saxon people of pre-unification England submitted to Alfred, he did not adopt the title King of England himself.

Alfred the Great introduced several military reforms. One, reported in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle's annal for 893, was the division of the fyrd into two "so that always half were at home and half on service". In 896, the annal reported that Alfred began to build ships to an enlarged sixty-oar design of his own. This reform resulted in some historians claiming that Alfred was the father of an English navy. The third major reform was "building a chain of forts around his kingdom, from Devon and Somerset to Sussex and Surrey." (23) He also creating a standing army that served for six months in every year. It has been claimed that "Alfred's defensive arrangements enabled the mass of the people to live and work in peace."

Alfred's close associate, John Assler, explained: "He (Alfred) was a bountiful giver of alms, both to his own countrymen and to foreigners of all nations, incomparably affable and pleasant to all men, and a skilful investigator of the secrets of nature. Many Franks, Frisians, Gauls, Pagans, Britons and Scots, and Bretons submitted voluntarily to his dominion, both noble and ignoble, all of whom, according to their birth and dignity, he ruled, loved, honoured, and enriched with money and power."

Douglas Woodruff has argued that Alfred introduced several important legal reforms. At that time Judgement by Ordeal was a widespread custom among the people of Britain. For example, someone accused of a crime might be made to eat a specially baked cake. It was believed if the person was lying, God would make sure he choked and died.

Ordeal by fire involved the accused plunging his bare arm into boiling water and fetch out a stone from the bottom of the vessel. His arm was then bandaged and left for three days. At the end of the time, priests, in the presence of witnesses, unbandaged the arm and if it was completely healed he would be acquitted. On other occasions a man would have to carry a very hot iron rod for a number of paces. The test of innocence was the burns should disappear in three days.

In about 890, Alfred issued a law code, consisting of his "own" laws followed by a code issued by his predecessor King Ine of Wessex. About a fifth of the law code is taken up by Alfred's introduction. Alfred encouraged the use of local courts where jurors knew something about the person accused of a crime. "The beginnings of the jury system rested on the principle that one of the best guides to who was telling the truth was the good name or the less good name that a man enjoyed among his neighbours. The guiding principle was exactly the opposite of what was later to become the essence of the jury system, that the jurors must have no previous knowledge of the parties to a suit and if possible no knowledge of the facts or preconceived opinions."

Alfred surrounded himself with scholars such as John Assler, Grimbald of St Bertin, John the Old Saxon and Plegemund of Mercia. He insisted that all his officials obtain wisdom (learnt to read). According to Patrick Wormald the "idea of wisdom observably drove Alfred's programme of spiritual and cultural revival". Alfred wanted his officials to learn Latin as well as English.

His biographer, John Assler, argues: "Meanwhile amid wars and the frequent hindrances of this present life, the incursions of the Pagans and his own daily infirmities of body, the King did not cease to carry on the government and to engage in hunting of every form; to teach his goldsmiths and all his artificers, his falconers, hawkers and dog-keepers; to erect by his own inventive skill finer and more sumptuous buildings than had ever been the wont of his ancestors; to read aloud Saxon books, and above all, not only to command others to learn Saxon poems by heart but to study them himself in private to the best of his power... Moreover, he loved his bishops and the whole order of clergy, his earls and nobles, and all his servants and friends with wonderful affection, and he looked upon their sons, who were brought up in the royal household, as no less dear to him than his own, never ceasing night and day, among other things, to instruct them in all good morals and to teach them letters."

Alfred the Great introduced a new education system. The emphasis was on a school at court itself rather than in the kingdom's major churches. Children of lesser as well as noble birth were schooled there. "The schooling was to begin in the vernacular, not for its own sake but, as Alfred said, to lay foundations on which Latin learning could then be built in those continuing to higher rank.... The vernacular received such a boost that English now became a language of prose literature, with all that was to mean for its survival."

Alfred decided to translate books into Anglo-Saxon. His first book was Pastoral Care, a treatise on the responsibilities of the clergy, that had been written by Pope Gregory I in about 590. This was followed by

History against the Pagans by Paulus Orosius. This book was written in about 416 and Alfred added a lot of historical information that was not in the original book. He also provided an Anglo-Saxon translation of Ecclesiastical History of the English People, a book that had been produced in Latin by Bede. It is this work that has given him the title of the "father of English prose".

In 892 the Danish commander Haesten sailed to England from Boulogne to the Kent coast. His army landed in 80 ships and occupied the village of Milton Regis, whilst his allies landed at Appledore with 250 ships. Alfred positioned his army between them to keep them from uniting, the result of which was that Hastein agreed terms, including allowing his two sons to be baptised, and left Kent and established a camp at Benfleet.

Hastein used this camp as a base to raid Mercia. Alfred's troops captured his fort, along with his ships, women and children. This included Hastein's own wife and sons. According to the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, Hastein negotiated the release of his family. Shortly afterwards, Hastein launched a second raid along the Thames valley and from there along the River Severn. Eventually they returned to the fortress at Shoeburyness. "After many weeks had passed, some of the heathens (Danes) died of hunger, but some, having by then eaten their horses, broke out of the fortress, and joined battle with those who were on the east bank of the river. But, when many thousands of pagans had been slain, and all the others had been put to flight, the Christians were masters of the place of death."

Alfred the Great died on 26th October 899. He was barely fifty. His successor was his son Edward the Elder. It has been claimed by his biographer, Patrick Wormald: "It is needless to endorse all that has been thought of Alfred as history transmuted into myth. The historical record plainly establishes that he was among the most remarkable rulers in the annals of human government."

Barbara Yorke has argued that "Alfred’s lack of a saintly epithet, a disadvantage in the high Middle Ages, was the salvation of his reputation in a post-Reformation world. As a pious king with an interest in promoting the use of English, Alfred was an ideal figurehead for the emerging English Protestant church". Archbishop Matthew Parker "did an important service to Alfred’s reputation by publishing an edition of Asser’s Life of Alfred in 1574."

John Foxe, the author of Foxe's Book of Martyrs (1563) also wrote favourably about Alfred. It has been argued that this is one of the most important books published in the English language: "The Book of Martyrs, with the full force of government propaganda behind it, undoubtedly had a powerful effect on the English people, and is one of the few books which can be said to have changed the course of history."

It was during the reign of Queen Victoria, that Alfred really gained his impressive reputation. Joanne Parker, argues in her book, England's Darling: The Victorian Cult of Alfred the Great (2007) that "the Saxon monarch became increasingly promoted as a moral role-model for everyone, and his personal achievements, accomplishments and character were investigated and discussed as much as his civic institutions and establishments." Parker quotes the Victorian historian, Edward Augustus Freeman, the author of The History of the Norman Conquest of England (1867-1879) as describing Alfred as "the most perfect character in history".

Charles Dickens also loved Alfred and in his book A Child’s History of England (1851-53) he puts forward the viewpoint that he was our greatest king: "As great and good in peace, as he was great and good at war, King Alfred never rested from his labours to improve his people. He loved to talk with clever men, and with travellers from foreign countries, and to write down what they told him, for his people to read.... He founded schools; he patiently heard causes himself in his Court of Justice; the great desires of his heart were to do right to all his subjects, and to leave England, better, wiser, happier in all ways, than he found it."

In the 20th century Alfred the Great was acclaimed by Marxist historians. A. L. Morton, the author of A People's History of England (1938) claims that his achievements in the field of education makes him "one of the greatest figures in English history". Morton points out: "Alfred encouraged learned men to come from Europe and even from Wales and in middle age taught himself to read and write in Latin and English... He sought eagerly for the best knowledge that the age afforded and in a less illiterate time would probably have attained a really scientific outlook. Constantly in ill health, never long in peace, the extent of his work is remarkable."

On this day in 1789 Richard Oastler, the son of a clothing merchant, was born in Leeds. Richard attended a Moravian boarding school from 1798 to 1810 and became a commission agent. Oaster did this job for ten years and in 1820 was appointed as steward for Thomas Thornhill, the absentee landlord of Fixby, a large estate near Huddersfield.

In 1830 Oastler met John Wood, a worsted manufacturer from Bradford, who agonised over the need to employ children in his factory. After a lengthy meeting Oastler decided to join the struggle for factory legislation.

Unlike most of the people in the factory reform movement, Oastler was a supporter of the Tory Party. He strongly opposed universal suffrage, trade unions and was a warm supporter of the rigid class structure of the early 19th century. However, Oastler believed it was the responsibility of the ruling class to protect the weak and vulnerable. For example, Oastler thought the 1834 Poor Law was too harsh and campaigned for it to be reformed.

Oastler thought the best way to protect children was to obtain a maximum ten hour day. He argued: "Very often the children are awakened by the parents at four in the morning. They are pulled out of bed when almost asleep. The younger children are carried on the backs of the older children asleep to the mill, and they see no more of their parents till they go home at night, and are sent to bed."

On 29th September 1830, Richard Oastler wrote a letter to the Leeds Mercury attacking the employment of young children in textile factories. John Hobhouse, the Radical M.P. read the letter and decided to introduce a bill restricting child labour. Hobhouse proposed that: (a) no child should work in a factory before the age of 9; (b) no one between the ages of 9 and 18 should work for more than twelve hours; (c) no one aged between the ages of 9 and 18 should work for more than 66 hours a week; (d) no one under 18 should be allowed to do night work.

After details of Hobhouse's Bill was published, workers began forming what became known as Short Time Committees in an effort to help promote its passage through Parliament. The first Short Time Committees were formed in Huddersfield and Leeds but within a few months, with the help of Richard Oastler, they were established in most of the major textile towns.

Parliament was dissolved in April, 1831 and so Hobhouse's Bill had to be reintroduced after the General Election. Hobhouse's proposals for factory legislation were discussed in Parliament in September 1831. Richard Oastler and the Short Time Committees were furious when Hobhouse agreed to make changes to his proposals. Although Hobhouse's Bill was passed it only applied to cotton factories and failed to provide any machinery for its enforcement.

Unhappy with what Hobhouse had achieved, the Short Time Committees continued to work for factory legislation. A magnificent orator, Richard Oastler soon became leader of what was now known as the Ten Hour Movement. In 1836 Oastler began advocating workers to use strikes and sabotage in their campaign for factory legislation and changes in the poor law. When Thomas Thornhill heard about this he sacked Oastler from his post as steward of Fixby. He also began legal proceedings against Oastler for unpaid debts. Unable to pay back the money he owed, Oastler was jailed for debt in December 1840. His friends began raising money to help him but it was not until February 1844 that the debt was paid and Oastler was released from Fleet Prison. Once released, Oastler returned to his campaign for the ten hour day.

In 1847, Parliament passed an act that stated that children between 13 and 18 and women were not to work for more than ten hours a day and 58 hours a week. However, the 1847 Factory Act only applied to parts of the textile industry. It was not until 1867, six years after the death of Richard Oastler, that the existing Factory Acts applied to all places of manufacturing.

On this day in 1851 Dora Montefiore, the eighth child of Francis and Mary Fuller, was born on 20th December, 1851. Her father was a land surveyor and railway entrepreneur. She was educated at home at Kenley Manor, near Coulsdon, and then at a private school in Brighton. According to Olive Banks: "There was a deeply affectionate relationship between father and daughter, and he obviously made great efforts to stimulate her intelligence.... she became his amanuensis, travelling with him and helping him prepare papers for the British Association and Social Science Congresses."

In 1874 she went to Australia, where she met George Barrow Montefiore, a wealthy businessman. After their marriage on 1st February 1881, they lived in Sydney, where their daughter was born in 1883 and their son in 1887. Her husband died on 17th July 1889. Although she had no personal grievances, she discovered that she had no rights of guardianship over her own children unless her husband had willed them to her. She therefore became an advocate of women's rights and in March 1891 she established the Womanhood Suffrage League of New South Wales.

On returning to England in 1892 she worked under Millicent Fawcett at the National Union of Suffrage Societies. She also joined the Social Democratic Federation and eventually served on its executive. She also contributed to its journal, Justice.

During the Boer War Montefiore "refused willingly to pay income tax, because payment of such tax went towards financing a war in the making of which I had had no voice." As she pointed out in her autobiography, From a Victorian to a Modern (1927): "In 1904 and 1905 a bailiff had been put in my house, a levy of my goods had been made, and they had been sold at public auction in Hammersmith. The result as far as publicity was concerned was half a dozen lines in the corner of some daily newspapers, stating the fact that Mrs. Montefiore’s goods had been distrained and sold for payment of income tax; and there the matter ended."

During this period she became close friends with Elizabeth Wolstenholme-Elmy who had also become dissatisfied with the slow progress towards women's suffrage. Both women joined the Women's Social and Political Union (WSPU) soon after it was formed in 1905. She worked closely with Sylvia Pankhurst and Annie Kenney as part of their London campaign.

In 1906 Dora Montefiore refused to pay her taxes until women were granted the vote. Outside her home she placed a banner that read: “Women should vote for the laws they obey and the taxes they pay.” As she explained: "I was doing this because the mass of non-qualified women could not demonstrate in the same way, and I was to that extent their spokeswoman. It was the crude fact of women’s political disability that had to be forced on an ignorant and indifferent public, and it was not for any particular Bill or Measure or restriction that I was putting myself to this loss and inconvenience by refusing year after year to pay income tax, until forced to do so by the powers behind the Law."

This resulted in her Hammersmith home being besieged by bailiffs for six weeks. "Towards the end of June, the time was approaching when, according to information brought in from outside the Crown had the power to break open my front door and seize my goods for distraint. I consulted with friends and we agreed that as this was a case of passive resistance, nothing could be done when that crisis came but allow the goods to be distrained without using violence on our part. When, therefore, at the end of those weeks the bailiff carried out his duties, he again moved what he considered sufficient goods to cover the debt and the sale was once again carried out at auction rooms in Hammersmith. A large number of sympathisers were present, but the force of twenty-two police which the Government considered necessary to protect the auctioneer during the proceedings was never required, because again we agreed that it was useless to resist force majeure when it came to technical violence on the part of, the authorities."

In October 1906 she was arrested during a WSPU demonstration and was sent to Holloway Prison. "The cells had a cement floor, whitewashed walls and a window high up so that one could not see out of it. It was barred outside and the glass was corrugated so that one could not even get a glimpse of the sky; and the only sign of outside life was the occasional flicker of the shadow of a bird as it flew outside across the window. The furnishing of the cell consisted of a wooden plank bed stood up against the wall, a mattress rolled up in one corner, two or three tin vessels, a cloth for cleaning and polishing and some bath brick. On the shelf were a Bible, a wooden spoon, a salt cellar, and one other book whose name I forget, but I remember glancing into it and thinking it would appeal to the intelligence of a child of eight. There was also a stool without a back, and inside the mattress when unrolled for the night and placed on the wooden stretcher were two thin blankets, a pillow and some rather soiled-looking sheets. One tin utensil was for holding water, the second for sanitary purposes, and the third was a small tin mug for holding cocoa."

Montefiore disagreed with the way Emmeline Pankhurst and Christabel Pankhurst were running the WSPU and in 1906 she left the organisation. However, she remained close to Sylvia Pankhurst, who shared a belief in socialism. Montefiore was not alone in her opinions of the leadership of the WSPU. These women objected to the way that the Pankhursts were making decisions without consulting members. They also felt that a small group of wealthy women like Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence were having too much influence over the organisation. In the autumn of 1907, Teresa Billington-Greig, Elizabeth How-Martyn, Dora Marsden, Helena Normanton, Margaret Nevinson and Charlotte Despard and seventy other members of the WSPU left to form the Women's Freedom League (WFL).

In 1907 Montefiore joined the Adult Suffrage Society and was elected its honorary secretary in 1909. She also remained in the Social Democratic Federation. Montefiore's biographer, Karen Hunt, has pointed out: "Within the SDF she developed a woman-focused socialism and helped set up the party's women's organization in 1904. An energetic although often dissident worker for the SDF until the end of 1912, Montefiore resigned from what had become the British Socialist Party as an anti-militarist."

Montefiore was pre-eminently a journalist and pamphleteer. She wrote a women's column in The New Age (1902–6) and in the Social Democratic Federation journal Justice (1909–10). Later she was to write for the Daily Herald and the New York Call. Most of her pamphlets were on women and socialism, for example, Some words to Socialist women (1907). Montefiore was also interested in an international apprach to women's suffrage and socialism and travelled a great number of congresses and conferences in Europe, the United States, Australia, and South Africa.

On 31st July, 1920, a group of revolutionary socialists attended a meeting at the Cannon Street Hotel in London. The men and women were members of various political groups including the British Socialist Party (BSP), the Socialist Labour Party (SLP), Prohibition and Reform Party (PRP) and the Workers' Socialist Federation (WSF).

It was agreed to form the Communist Party of Great Britain (CPGB). Early members included Dora Montefiore, Tom Bell, Willie Paul, Arthur McManus, Harry Pollitt, Rajani Palme Dutt, Helen Crawfurd, A. J. Cook, Albert Inkpin, J. T. Murphy, Arthur Horner, Rose Cohen, Tom Mann, Ralph Bates, Winifred Bates, Rose Kerrigan, Peter Kerrigan, Bert Overton, Hugh Slater, Ralph Fox, Dave Springhill, William Mellor, John R. Campbell, Bob Stewart, Shapurji Saklatvala, George Aitken, Dora Montefiore, Sylvia Pankhurst and Robin Page Arnot. McManus was elected as the party's first chairman and Bell and Pollitt became the party's first full-time workers.

After the death of her son from the effects of mustard gas in 1921 (he had been gassed while serving on the Western Front during the First World War), she joined his widow and children in Australia. In 1927 she published her autobiography, From a Victorian to a Modern.

Dora Montefiore died on 21st December 1933, at her home in Hastings, and was cremated at Golders Green, Middlesex.

On this day in 1865 Maud Gonne, the daughter of a colonel in the British Army. After her mother's early death she was sent to be educated in Paris. Her father was from a wealth Irish family and in 1882 she joined him in Dublin.

Maude Gonne's father died in 1886 and left her financially independent. She returned to France where she met and fell in love with the radical journalist, Lucien Millevoye. Influenced by Millevoye's political views, Maud became involved in radical politics.

Maude Gonne moved to Ireland and settled in Donegal where she was active in the campaign to protect those evicted from their homes. This included building huts, fund-raising and writing to newspapers. Threatened with arrest, Maud fled to France in 1890 where she gave birth to Millevoye's child. While living in Paris she edited L'Irlande Libre, a monthly journal that promoted Irish independence.

In 1900 Maud Gonne ended her relationship with Millevoye and returned to Ireland where she founded the revolutionary group, the Daughters of Erin. The organization also produced the monthly journal, The Irish Woman, and she contributed several articles on feminist and political topics.

Together with William Butler Yeats Maude Gonne helped establish the Abbey Theatre in Dublin. Yeats fell in love with her and his feelings for her inspired a large number of poems. In 1902 Gonne played the leading role in his play, Kathleen Ni Houlihan.

In 1903 Maude Gonne married John MacBride, a major of the Irish Brigade. After giving birth to Seán MacBride, she joined Constance Markievicz, James Connolly and James Larkin in the campaign to force the authorities to extend the 1906 Provision of School Meals Act to Ireland. She also started a scheme to feed poor children in Dublin.

During the First World War Maud joined Constance Markievicz, Hanna Sheehy Skeffington and Kathleen Clarke in the campaign against the conscription of Irish men into the British Army.

On 5th May 1916 John MacBride was executed for his part in the Easter Rising. Maud continued to campaign against conscription and in 1918 she was arrested and interned in Holloway Prison in London.

After her release Maud Gonne returned to Ireland and worked for the White Cross, an organization that helped the victims of the War of Independence and their dependents. Together with Charlotte Despard she collected first-hand evidence of army and police atrocities in Cork and Kerry. The two women also formed the Women's Prisoners' Defence League to support republican prisoners.

In 1923 Maude Gonne was imprisoned without charge by the Free State government and was one of the 91 women who went on hunger strike while in prison.

Maude Gonne's son, Seán MacBride, also became involved in politics and in 1936 became Chief of Staff of the Irish Republican Army. In 1938, she published her memoirs, A Servant of the Queen.

Maud Gonne died at Roebuck, Clonskeagh, on 27th April, 1953 and afterwards was buried in the Republican Plot in Glasnevin Cemetery, Dublin.

On this day in 1880 Olive Hockin, was born in Bude, Cornwall, on 20th December, 1880. Her father, Edward Hockin (1838-1880), was a wealthy landowner and her mother Margaret Sarah Hoyer (1855-1919), was a clergyman's daughter.

As a teenager she spent time in Buenos Aires, Argentina. She returned to London in 1897 to study at the Slade School of Fine Art where she took a mixture of full and part-time courses.

Hockin was a contributor to Orpheus, the journal of the Theosophical Society. The editorial of the journal stated "we are a group of artists who revolt against the materialism of most contemporary art. We are adherents of that ancient philosophic idealism which is known to our times as theosophy." In the first few editions the journal included a reproduction of her paintings, The Blue Closet and A Phantast. She also wrote a an article Impressions of the Italian Futurist Painters.

Hockin joined the Women's Social and Political Union (WSPU) in 1912. Its newspaper, Votes for Women, reported that she had become "a new worker in our movement" and was producing banners for the Bastille Day rally that was to take part in Hyde Park on 14th July 1912. Later she said she joined "the movement, and had worked in it heart and soul, because it was a deeply rooted conviction that the world would be fairer and the conditions of life better for men, as well as for women and children, if women shared in the government."

In July 1912, Emmeline Pankhurst gave permission for Christabel Pankhurst, to launch a secret arson campaign. She knew that she was likely to be arrested and so she decided to move to Paris. In January 1913, Emmeline Pankhurst made a speech where she stated that it was now clear that Herbert Asquith had no intention to introduce legislation that would give women the vote. She now declared war on the government and took full responsibility for all acts of militancy. "Over the next eighteen months, the WSPU was increasingly driven underground as it engaged in destruction of property, including setting fire to pillar boxes, raising false fire alarms, arson and bombing, attacking art treasures, large-scale window smashing campaigns, the cutting of telegraph and telephone wires, and damaging golf courses".

The WSPU used a secret group called Young Hot Bloods to carry out these acts. No married women were eligible for membership. The existence of the group remained a closely guarded secret until May 1913, when it was uncovered by the conspiracy trial of eight members of the suffragette leadership, including Flora Drummond, Annie Kenney and Rachel Barrett. It has speculated that this group included Olive Hockin, Helen Craggs, Kitty Marion, Lilian Lenton, Miriam Pratt, Norah Smyth, Clara Giveen, Hilda Burkitt, Olive Wharry and Florence Tunks.

On 19th February, 1913, an attempt was made to blow up a house which was being built for David Lloyd George, the Chancellor of the Exchequer, near Walton Heath Golf Links. "One device had exploded, causing about £500 worth of damage, while another had failed to ignite." Sir George Riddell who had commissioned the house, wrote in his diary that Lloyd George: "Said the facts had not been brought out and that no proper point had been made of the fact that the bombs had been concealed in cupboards, which must have resulted in the death of 12 men had not the bomb which first exploded blown out the candle attached to the second bomb, which had been discovered, hidden away as it was. He was very indignant." Lloyd George wrote to Riddell and apologised for being "such a troublesome and expensive tenant" and that the WSPU should be made to pay for the damage.

That evening in a speech at Cory Hall, Cardiff, Emmeline Pankhurst declared "we have blown up the Chancellor of Exchequer's house' and stated that "for all that has been done in the past I accept responsibility. I have advised, I have incited, I have conspired". Pankhurst concluded that extreme methods were needed because "No measure worth having has been won in any other way."

Emmeline Pankhurst was arrested and charged with "incitement to commit arson". On 3rd April she was sentenced to three years' penal servitude and immediately went on hunger strike. No attempt was ever made to feed her forcibly and the Prisoners' (Temporary Discharge for Ill Health) Bill (Cat & Mouse Act), which allowed hunger-striking prisoners to be released to recover their health before being returned to prison, was rushed through to ensure that she did not die in prison.

Police records show that the police suspected Olive Hockin and Norah Smyth of being the people who had carried out the attempt to blow up Lloyd George's house. As Elizabeth Crawford has pointed out: "It is clear from the New Scotland Yard reports of the investigation that Olive Hockin's address had been under surveillance. Her absence from home, the manner of her departure and the time of her return are all noted in the police report."

On 12th March 1913 the police raided Olive Hockin's flat as she was suspected an arson attack on Roehampton Golf Club. In the flat they discovered a "suffragette arsenal" that included "a perfect arsenal of implements of destruction, including bottles of corrosive fluid, clippers for cutting telegraph wires, fire lighters, hammers, flints, tools of all descriptions in addition to a number of false motor-car identification plates, etc..."

Olive Hockin was charged with "conspiring with others unknown to set fire to the croquet pavilion, the property of Roehampton Golf Club (26 February), to commit damage to an orchid house at Kew Gardens (8 February) and to cut telephone wires on various dates", and with "placing certain fluid in a Post Office letter-box in Ladbroke Grove (12 March)". At her trial it was disclosed that a copy of the Daily Herald and of The Suffragette, which was found inside the dropped bag had her name and address penciled on them. Her caretaker later identified the handwriting as that of their local newsagents.

At her trial Hockin admitted that she had been drawn into the militant suffrage movement after she became aware of the evils of prostitution. In court it was stated that Hockin had been seen by "a police officer to ride a bicycle along the High Street, Notting Hill, and turn into Ladbroke Road, where the pillar-box stood. When the officer got up to the letter-box he saw some fluid trickling out of the bottom."

In court it was admitted that Olive Hockin had been under surveillance for several weeks and on 26th February, the night of the attack in Roehampton, Hockin was seen to be acting suspiciously. Votes for Women reported: "In the evening a motor-car, driven by a lady, stopped at the house. Some parcels and long rods were taken out of the studio and strapped to the side of the car. The defendant (Olive Hockin) and another lady left in the car at about 10.30." About four o'clock the next morning the witness heard the front door bang and someone pass up the stairs to the studio. Later in the morning Miss Hockin said she was sorry that the door banged, but 'the young lady did not know how to manage the door'. The witness "stated that Miss Hockin did not sleep at the studio on the night of the Roehampton affair."

Mrs Hall, her landlady, pointed out that the following morning Olive Hockin left out two pairs of boots to be cleaned, and only one pair of which belonged to the prisoner. The second pair had mud and grass on them, at the sight of which Mrs Hall remembered reading an article about a fire at the Roehampton Pavilion. Later that day Mrs Hall heard Hockin being visited by two young women carrying gentleman's "dressing-cases".

Olive Hockin claimed she was not guilty of these charges. She also objected to the male dominated justice system: "A court composed entirely of men have no moral right to convict and sentence a woman, and until women have the power of voting I shall continue to defy the law, whether I am in prison or out of it."

Judge Charles Montague Lush formally withdrew the charges relating to the attack on the orchid house, telephone-wire cutting and the pillar-box attack,. His summing-up showed sympathy for Olive Hockin and commented there was no evidence that she was present at Roehampton. Lush also controversially commented that she was a "woman who in her zeal had joined in a cause which she thought was a thoroughly good cause, and she might be right in thinking so." Olive was sentenced to four months imprisonment and ordered to pay half the costs of the prosecution.

Soon after her arrival surveillance photographs of Olive Hockin were taken from a van parked in the prison exercise yard. Olive appears with Margaret Schenke, Jane Short and Margaret Mcfarlane. The images were compiled into photographic lists of key suspects, used to try and identify and arrest Suffragettes before they could commit militant acts.

Olive Hockin threatened to go on hunger strike and it was transferred to the First Division, and agreed to serve her sentence on condition of being permitted to carry on as an artist in prison. (29) Margaret Schenke claimed that she carved the chair in her cell.

Sylvia Pankhurst grew increasingly unhappy about the Women's Social and Political Union (WSPU) decision to abandon its earlier commitment to socialism. She also rejected the WSPU attempts to gain middle class support by arguing in favour of a limited franchise. Pankhurst made the final break with the WSPU when the movement adopted a policy of widespread arson. Sylvia now concentrated her efforts on helping the Labour Party build up its support in London.

In 1913, Sylvia Pankhurst, with the help of Keir Hardie, Julia Scurr, Mary Phillips, Millie Lansbury, Eveline Haverfield, Lilian Dove-Wilcox, Maud Joachim, Nellie Cressall and George Lansbury established the East London Federation of Suffragettes (ELF). An organisation that combined socialism with a demand for women's suffrage it worked closely with the Independent Labour Party. Pankhurst also began production of a weekly paper for working-class women called The Women's Dreadnought.

As June Hannam has pointed out: "The ELF was successful in gaining support from working women and also from dock workers. The ELF organized suffrage demonstrations and its members carried out acts of militancy. Between February 1913 and August 1914 Sylvia was arrested eight times. After the passing of the Prisoners' Temporary Discharge for Ill Health Act of 1913 (known as the Cat and Mouse Act) she was frequently released for short periods to recuperate from hunger striking and was carried on a stretcher by supporters in the East End so that she could attend meetings and processions. When the police came to re-arrest her this usually led to fights with members of the community which encouraged Sylvia to organize a people's army to defend suffragettes and dock workers. She also drew on East End traditions by calling for rent strikes to support the demand for the vote."

On her release from prison Olive Hockin left the Women's Social and Political Union (WSPU) and joined the East London Federation of Suffragettes (ELF). Sylvia Pankhurst, known as "Our Sylvia", operating from her shop in Bow Road, recruited women who were working in local factories and sweatshops. Branches were formed in Bow & Bromley, Stepney, Limehouse, Bethnal Green, Hackney and West Ham. Hockin organised the Poplar branch that she ran from her home at 28 Campden Hill Gardens, Kensington.

Olive Hockin continued to work as an artist and produced one of her most important paintings, Pan! Pan! O Pan! Bring Back thy Reign Again Upon the Earth (1914) during this period. She continued exhibiting at the Society of Women Artists, at the Walker Art Gallery and the Royal Academy.

With growing numbers of men joining the British armed forces during the First World War, the country was desperately short of labour. The Government decided that more women would have to become more involved in producing food and goods to support their war effort. This included the establishment of the Women's Land Army. According to her own account, she had "just walked up to offer my services' to a Dartmoor farmer, after having seen his advertisement for a casual labourer." She saw his wife first who commented: "Well really! You must come in and tell me about it. I am afraid my husband only laughs at the idea. He says that a woman about the place would be more trouble than she is worth, and we quite made up our minds that no woman could possibly do the work!"' In 1918 she published her own account of her experiences, Two Girls on the Land: Wartime on a Dartmoor Farm.

The book was favourably reviewed in the The Common Cause, the newspaper of the National Union of Women's Suffrage Societies. "There is no attempt to cloak the real grind of hard days that lie behind the phrase "work on the land". Here you have it all clearly stated - the long, long hours, the consistent pressure of work, the mud in the winter, the heat in the summer - and through it all the things that competence and make one glad to one's best to "carry on". It is not possible here to set out the many paragraphs worth quoting, but to anyone who reads the book I can testify to the truth of every line."

In the summer of 1922 she married John Leared, the proprietor of a Cheltenham polo-pony training school. She became the mother of two sons, Oliver Leared (born 1926) and Nicholas Leared (born 1929). The family lived at Colmans, Elmstone Hardwicke.

Olive Hockin died at Cheltenham, Gloucestershire, on 5th February, 1936.

On this day in 1902 Prince George, Duke of Kent was born. George Saxe-Coburg-Gotha was the son of George, Prince of Wales, who was the son of Edward VII and Queen Alexandra. At the time of his birth, George was fifth in the line of succession.

Edward VII died in 1910 and Prince George's father, George V became the new king. The outbreak of the First World War created problems for the royal family because of its German background. Owing to strong anti-German feeling in Britain, it was decided to change the name of the royal family from Saxe-Coburg-Gotha to Windsor. To stress his support for the British, the king made several visits to the Western Front. On one visit to France in 1915 he fell off his horse and broke his pelvis.

At the age of thirteen Prince George went to Osborne Naval College. Later he transferred to Dartmouth College and served in the Royal Navy on board the Iron Duke and the Nelson.

In 1917 George V took the controversial decision to deny political asylum to the Tsar Nicholas II and his family after the Bolshevik Revolution. People where shocked by George's unwillingness to protect his cousin but his advisers argued that it was important for the king to distance himself from the autocratic Russian royal family. Some people questioned this decision when it became known that the Bolsheviks had executed Tsar Nicholas, his wife and their five children.

In 1924 George V appointed Ramsay MacDonald, Britain's first Labour Prime Minister. Two years later he played an important role in persuading the Conservative Government not to take an unduly aggressive attitude towards the unions during the General Strike.

Prince George remained in the Royal Navy until 1929. He then held posts in the Foreign Office and the Home Office. In 1934 George married Princess of Marina of Yugoslavia. At the same time he was granted the title of the Duke of Kent. Like his brother Edward, the Duke of Kent was sympathetic to the political developments that were taking place in Nazi Germany.

George V died of influenza on 20th January, 1936. George's brother, Edward VIII now became king. At the time he was having a relationship with Wallis Simpson. The government instructed the British press not to refer to the relationship. The prime minister, Stanley Baldwin, urged the king to consider the constitutional problems of marrying a divorced woman.

Although the king received the political support from Winston Churchill and Lord Beaverbrook, he was aware that his decision to marry Wallis Simpson would be unpopular with the British public. The Archbishop of Canterbury also made it clear he was strongly opposed to the king's relationship.

The government was also aware that Simpson was in fact involved in other sexual relationships. This included a married car mechanic and salesman called Guy Trundle and Edward Fitzgerald, Duke of Leinster. More importantly, the Federal Bureau of Investigation believed that Simpson was having a relationship with Joachim von Ribbentrop, the German Ambassador to Britain, and that she was passing secret information obtained from the king to the Nazi government.

On 10th December, 1936, the king signed a document that stated he he had renounced "the throne for myself and my descendants." The following day he made a radio broadcast where he told the nation that he had abdicated because he found he could not "discharge the duties of king as I would wish to do without the help and support of the woman I love."

George VI now became king and the coronation took place on 12th May, 1937. Later that month, Neville Chamberlain replaced Stanley Baldwin as prime-minister. The following year Chamberlain travelled to Nazi Germany to meet Adolf Hitler in an attempt to avoid war between the two countries.

The result of Chamberlain's appeasement policy was the signing of the Munich Agreement. George VI wrote to Chamberlain on hearing the news: "I am sending this letter by my Lord Chamberlain, to ask you if you will come straight to Buckingham Palace, so that I can express to you personally my most heartfelt congratulations on the success of your visit to Munich. In the meantime this letter brings the warmest of welcomes to one who by his patience and determination has earned the lasting gratitude of his fellow countrymen throughout the Empire."

Prince George shared his brother's view of appeasement and was considered the leader of the Anglo-German peace group. According to the authors of Double Standards (2001) the Duke of Kent met Rudolf Hess and Alfred Rosenberg during the 1930s. A report written by Rosenberg for Adolf Hitler in October 1935 stated that the Duke of Kent was working behind the scenes "in strengthening the pressure for a reconstruction of the Cabinet and mainly towards beginning the movement in the direction of Germany."

In February 1937 it was reported that the Duke of Kent had met the Duke of Windsor in Austria. Later that year a Foreign Office document pointed out that the Duke of Kent had developed a close relationship with Joachim von Ribbentrop, the German Ambassador in London.

By 1938 British intelligence was becoming very concerned about the activities of the Nazi spy, Princess Stephanie von Hohenlohe. A report said: "She is frequently summoned by the Führer who appreciates her intelligence and good advice. She is perhaps the only woman who can exercise any influence on him." They also reported that she seemed to be "actively recruiting these British aristocrats in order to promote Nazi sympathies." (PROKV2/1696).

According to MI5 the list of people she had been associating with over the last few years included Prince George, the Duke of Windsor, Wallis Simpson, Ethel Snowden, Philip Henry Kerr (Lord Lothian), Geoffrey Dawson, Hugh Grosvenor, 2nd Duke of Westminster, Charles Vane-Tempest-Stewart, 7th Marquess of Londonderry, Ronald Nall-Cain, 2nd Baron Brocket, Lady Maud Cunard and Walter Rothschild, 2nd Baron Rothschild. In August 1938 French intelligence, the Deuxième Bureau, told MI6 that it was almost certain that Princess Stephanie was an important German agent.

The Duke of Kent took part in secret talks with his cousin Prince Philip of Hesse in early 1939 in order to avoid a war with Nazi Germany. In July 1939, the Duke of Kent he approached George VI with a plan to negotiate directly with Adolf Hitler. The king, who supported the idea, spoke to Neville Chamberlain and Lord Halifax about the plan.

On the outbreak of the Second World War the Duke of Kent and his family moved to Scotland, living in Pitliver House, near Rosyth, in Fife. He returned to active military service at the rank of Rear Admiral, briefly serving on the Intelligence Division of the Admiralty. In April 1940, he transferred to the Royal Air Force. He took the post of Staff Officer in the RAF Training Command at the rank of Air Commodore.

In 1940 the Duke of Kent travelled to Lisbon to meet the dictator of Portugal, Antonio Salazar. The Duke of Windsor, who was in Madrid at the time, planned to meet his brother while he was in Lisbon. British officials were instructed to prevent the former king from going to Portugal until the Duke of Kent had left the country.

On 10th May, 1941, Rudolf Hess flew a Me 110 to Scotland with the intention of having a meeting with the Duke of Hamilton. Hess hoped that Hamilton would arrange for him to meet George VI. According to the authors of Double Standards (2001) the Duke of Kent was with Hamilton at his home (Dungavel House) on the night that Hess arrived in Scotland. As the Duke of Kent's papers are embargoed it is impossible to confirm this story. However, we do know from other sources he was at RAF Sumburgh in the Shetlands on the 9th and at Balmoral in Scotland on the 11th of May. The following day he was at RAF Wick at Caithness. He was therefore definitely in that area during this period.

The Duke of Hamilton's diary records several meetings with the Duke of Kent during the early months of 1941. Elizabeth Byrd worked as a secretary for Hamilton's brother Lord Malcolm Douglas-Hamilton. She claims he told her that the Duke of Hamilton took the "flak for the whole Hess affair in order to protect others even higher up the social scale". Byrd added that "he (Lord Malcolm) had strongly hinted that the cover-up was necessary to protect the reputations of members of the Royal Family".

On 25th August 1942, Prince George, Duke of Kent, took off from Invergordon in an S-25 Sunderland Mk III Flying Boat. The official story is the Duke was on a morale-boosting visit to RAF personnel stationed in Iceland. The crew had been carefully selected for the task. The captain, Flight Lieutenant Frank Goyen, was considered to be Sunderland flyer in the RAF and had flown some of Britain’s politicians during the war. The rest of the crew was also highly regarded. The co-pilot was Wing Commander Thomas Lawton Mosley, the commanding officer of 228 Squadron. Mosley was one of the RAF’s most experienced pilots having completed 1,449 flying hours. He was also a navigation specialist and was a former instructor at the School of Navigation.

Officially the Duke of Kent was one of fifteen people on board the aircraft. Also on board were Prince George’s private secretary (John Lowther), his equerry (Michael Strutt) and his valet (John Hales). The flying boat took off from Invergordon on the east coast of Scotland at 1.10 p.m. Being a flying boat, its standing orders were to fly over water, only crossing land when absolutely unavoidable. The route was to follow the coastline to Duncansby Head – the northernmost tip of Scotland – and then turn northwest over the Pentland Firth towards Iceland.

The S-25 Sunderland Mk III crashed into Eagle’s Rock later that afternoon (there is much dispute about the exact time this happened) at a height of around 650 feet. The flying boat was well off course when the accident happened. Its 2,500 gallons of fuel, carried in the wings, exploded.This raises some important questions. Why did the pilot take the flying boat off course? It was a clear day and he would be fully aware that he was now flying over land rather than the sea. Why, when the aircraft included four experienced navigators, did the aircraft drift a huge 15 degrees off course from its point of departure? Why did he descend to 650 feet when he was flying over high land? This is especially puzzling when one considers that the S-25 Sunderland Mk III had one major defect – it was sluggish when climbing – especially when heavily laden, as it was on the Duke of Kent’s flight.

The crash was heard by local people and reached the scene of the accident about 90 minutes after they heard the explosion. This included a doctor (John Kennedy) and two policemen (Will Bethune and James Sutherland). They found 15 bodies. This included the body of the Duke of Kent. Bethune gave a radio interview in 1985 where he described finding Prince George’s body. He said that handcuffed to the Duke’s wrist was an attaché case that had burst open, scattering a large number of hundred-kroner notes over the hillside.

The Duchess of Kent, collapsed in shock when she heard the news. The following morning the newspapers reported that everyone on board the Sunderland had been killed. Telegrams were sent to the next of kin of all members of the crew. However, later that day it emerged that Andy Jack, the tail-gunner, had been found in a crofter’s cottage at Ramscraigs. Apparently, when the flying boat exploded, the tail section was thrown over the brow of the hill, coming to rest in the peat bog on the other side. Andy Jack only had superficial injuries. What he did next was very surprising. Instead of going to the wreckage to see what had happened to his colleagues, and waiting for rescuers to arrive, he ran away in the opposite direction. This of course was in direct contravention of standard procedure – which was always to remain with the wreck. Andy Jack eventually found an isolated crofter’s cottage. The owner, Elsie Sutherland alerted Dr. John Kennedy by telephone. However, it was sometime before this information reached the authorities. Andy Jack’s sister Jean had already received a telegram telling her that her brother had been killed in the accident.

Winston Churchill made a statement in the House of Commons where he described the Duke of Kent as “a gallant and handsome prince”. Of the many tributes and messages of condolence received from other countries, the most significant was from General Wladyslaw Sikorski, the head of the Polish government in exile. The two men were very close and Sikorski sent a special dispatch to all Polish troops in Britain where he described the Duke as “a proven friend of Poland and the Polish armed forces”.

The Duchess of Kent visited Andy Jack several times after the death of her husband. It is believed that the information he provided influenced what was inscribed on the Duke of George’s memorial. This included the following: “In memory of…. the Duke of Kent… and his companions who lost their lives on active service during a flight to Iceland on a special mission on 25th August 1942”. The use of the words “special mission” is an interesting one. It was also the words used by Pilot Officer George Saunders, who also died in the crash. In 2001 Peter Brown, the nephew of Saunders, told a researcher that he was told that in August 1942, Saunders went home to see his family in Sheffield. Saunders informed his mother: “I’m just on leave for a couple of days. I’m going on a most important mission, very secret. I can’t say any more.”

A court of inquiry was held and details of their findings were presented in the House of Commons by the Secretary of State for Air, Archibald Sinclair, on 7th October 1942. The conclusion of the report was: “Accident due to aircraft being on wrong track at too low altitude to clear rising ground on track. Captain of aircraft changed flight-plan for reasons unknown and descended through cloud without making sure he was over water and crashed.”

Sinclair confirmed that weather conditions were fine and there was no evidence of mechanical failure. He added “the responsibility for this serious mistake in airmanship lies with the captain of the aircraft”. It was therefore suggested that the reason for the crash was the team of four pilot/navigators drifted off course and then failed to reach the necessary height to clear Eagle Rock.

The problem is that the documents that would enable researchers to re-examine the evidence have vanished. This includes the flight plan filed by Goyen before take-off.

The secret court of inquiry should have been made available after 15 years. When researchers asked the Public Record Office in 1990 for a copy of the report it was discovered that it had gone missing. The PRO suggested it might have been transferred to the royal archives at Windsor Castle. However, the registrar of the royal archives denies they have ever had the report.

Andy Jack, the only survivor of the crash, was forced to sign the Official Secrets Act while still in hospital. He later told his sister that he could not talk about the crash because he had been “sworn to secrecy”. Jean Jack did provide researchers with one piece of interesting information about the case. Frank Goyen gave Andy Jack a signed photograph of himself just before take-off on which he had written: “With memories of happier days.” Was this a reference to the mission they were about to undertake? Does it suggest that Goyen disapproved of the mission?

Andy Jack was promoted and after the war served in Gibraltar. While he was there he was visited several times by the Duchess of Kent. Clearly, she was still interested in finding out why her husband was killed.

On 17th May 1961 the Duchess of Kent brought the case to national attention when she visited the scene of her husband’s death. This created a discussion about the crash in the media. Andy Jack now came forward to give an interview to the Scottish Daily Express. He was still serving with the RAF and not surprisingly he went along with the conclusions of the official inquiry. He retired from the RAF on a good pension in 1964. However, he drunk away his money and died of cirrhosis of the liver at the age of fifty-seven.

An important witness to the crash was Captain E. E. Fresson. He piloted an aircraft over the same area and at around the same time as the crashed Flying Boat. The following day he took the only aerial photographs of the wreckage. In 1963 Fresson published his autobiography, Air Road to the Isles. Amazingly, the book does not refer to the death of the Duke of Kent. According to his son, Richard Fresson, the book originally included a full chapter that covered his investigation into the crash. However, this material was removed by the publishers at the last moment.

There is also another interesting aspect to this story. Just ten days after the death of the Duke of Kent, another flying boat, also from 228 Squadron, crashed in the Scottish Highlands. The official explanation was that the plane had run out of fuel. Everyone on board was killed, including a very interesting passenger, Fred Nancarrow, a journalist from Glasgow. Nancarrow was investigating the Eagle Rock crash.

On this day in 1902 Sidney Hook, the son of Isaac and Jennie Hook, was born in Brooklyn. His parents were Austrian Jewish immigrants and they lived in Williamsburg. Hook's family lived in extreme poverty. He explained in his autobiography, Out of Step: An Unquiet Life in the 20th Century (1987): "The physical conditions under which we lived were quite primitive. On Locust Street where we lived for some years, the toilets were in the yard. In other tenements they were shared with another family. All were railroad flats, heated only by a coal stove and boiler in the kitchen. Gas provided illumination and the most common means of suicide. We froze in winter and fried in summer. Vermin were almost always a problem, and the smell of kerosene pervaded our bedrooms, which had no windows and gave on skylights instead. The public baths were used until bathtubs were installed. The women worked like pack horses; their work was never done. Nor could their husbands have shared their household labors. My father left for work before we arose; he returned from work when we were ready to go to bed. More than once, to the astonishment and amusement of the children, he would fall asleep at the dinner table with the soup spoon in his hand poised in the air."

At the age of 13 Sidney Hook became a socialist. He was introduced to the ideas of Eugene Debs by a schoolmate whose father "had imbued his son with an enthusiasm that bordered on the fanatical". As a result of this friendship Hook became a "faithful reader" of the New York Socialist Call newspaper. Hook also read pamphlets written by Daniel DeLeon. However, the most important influence at the time was the work of the novelist, Jack London: "The most profound source of the Socialist appeal, was its moral concern, its sense of human fraternity, its emphasis upon equality of opportunity for all, its view that what men have in common - their human condition in life and death - was more significant than the racial, national, and other parachial differences that separated them."

Hook was totally opposed to the United States involvement in the First World War and the Espionage Act that was passed by Congress in 1917. It prescribed a $10,000 fine and 20 years' imprisonment for interfering with the recruiting of troops or the disclosure of information dealing with national defence. Additional penalties were included for the refusal to perform military duty. Over the next few months around 900 went to prison under the Espionage Act. Criticised as unconstitutional, the act resulted in the imprisonment of many of the anti-war movement. This included the arrest of left-wing political figures such as Eugene V. Debs, Bill Haywood, Philip Randolph, Victor Berger, John Reed, Max Eastman, Martin Abern and Emma Goldman.

Hook was also a supporter of the Russian Revolution. He did not agree with the closing down of the Consit and the banning of the opposition parties but as he explained: "The first doubts began to emerge only after the Russian October Revolution, when the voices of Menshevik and Anarchist protest reached us, but only faintly. These voices and our doubts were drowned out by the thunder of the counterrevolutionary armies of Denikin, Kolchak, Yudenich, and the remarkable propaganda of the Bolsheviks, whose mastery of all the media of modern communication has remained unsurpassed from that day to this."

In 1919 Hook began studying philosophy at the College of the City of New York. His main lecturer was Harry Overstreet who had been influenced by the teaching of John Dewey. "Professor Harry Overstreet, chairman of the Department of Philosophy... had been converted to John Dewey's conception of philosophy, but unfortunately he did not hold up his end of the technical arguments when challenged by philosophy students... Nor was he highly regarded by fanatical young Socialists, to whom he was a mere social reformer whose ineffectual programs made more difficult the radicalization of the working class."

Hook later recalled how Overstreet reacted to what became known as the Red Scare: "Overstreet would flare up with an eloquent outburst of denunciation at some particularly outrageous act of oppression. This was especially hazardous during the days of the Palmer raids and subsequent deportations. There were few organized protests against these brutal highhanded measures that crassly violated the key provisions of the Bill of Rights. The general public reacted to the excesses as if they were a passing heat wave. In the postwar hysteria of the time, it seemed as if the public either supported these measures or, more likely, was indifferent to them."

A. Mitchell Palmer claimed that Communist agents from Russia were planning to overthrow the American government. On 7th November, 1919, the second anniversary of the Russian Revolution, over 10,000 suspected communists and anarchists were arrested. Palmer and Hoover found no evidence of a proposed revolution but large number of these suspects were held without trial for a long time. The vast majority were eventually released but Emma Goldman, Alexander Berkman, Mollie Steimer, and 245 other people, were deported to Russia.

Hook was also deeply influenced by the teaching of Morris Cohen. He explained in Out of Step: An Unquiet Life in the 20th Century (1987): "One of the great teachers of the first third of our century was Morris R. Cohen of the College of the City of New York, where he taught courses in philosophy from 1912 to 1938. By conventional pedagogical standards, he would not be considered a great or even a good teacher, for he inspired only a few of his students to undertake careers in philosophy and overawed the rest. Nonetheless his prowess as a teacher became legendary and his ideas a force in the intellectual community. Yet his classroom techniques would never have won him tenure in any public school system, and he himself confessed he was a failure in his early efforts as an elementary and secondary schoolteacher, because he could not even control his classes."

While at university Hook became a devoted follower of John Dewey. "My familiarity with Dewey's writings began at the College of the City of New York. I had enrolled in an elective course in social philosophy with Professor Harry Overstreet, who was a great admirer of Dewey's and spoke of him with awe and bated breath. The text of the course was Dewey's Reconstruction in Philosophy, which we read closely. Before I graduated, and in connection with courses in education, I read some of Dewey's Democracy and Education and was much impressed with its philosophy of education, without grasping at that time its general significance... What did impress me about Reconstruction in Philosophy, and later other writings of Dewey, was the brilliant application of the principles of historical materialism, as I understood them then as an avowed young Marxist, to philosophical thought, especially Greek thought. Most Marxist writers, including Marx and Engels themselves, made pronouncements about the influence of the mode of economic production on the development of cultural and philosophical systems of thought, but Dewey, without regarding himself as a Marxist or invoking its approach, tried to show in detail how social stratification and class struggles got expressed in the metaphysical dualism of the time and in the dominant conceptions of matter and form, body and soul, theory and practice, truth, reason, and experience. However, even at that time I was not an orthodox Marxist. Although politically sympathetic to all of the social revolutionary programs of Marxism, and in complete agreement with Dewey's commitment to far-reaching social reforms, I had a much more traditional view of philosophy as an autonomous discipline concerned with perennial problems whose solution was the goal of philosophical inquiry and knowledge.... In that period he was indisputably the intellectual leader of the liberal community in the United States, and even his academic colleagues at Columbia and elsewhere who did not share his philosophical persuasion acknowledged his eminence as a kind of intellectual tribune of progressive causes."

On 9th April, 1923, Sidney Hook began teaching in the elementary school system in New York City. "Compared to the most recent disciplinary cases in our ghetto or slum schools, these students were only mildly disorderly. The drug scene was still many years in the future, and although many carried vicious pocket knives honed to razor-sharp thinness, the switchblade had not yet come into use. Half of the class seemed genuinely dull or backward, half were quick-witted but restless and undisciplined. Although most were native-born, their use of English was extremely primitive.... The students feared their parents and the truant officer more than their teacher, and came up with all sorts of original ailments and domestic calamities to win freedom from classroom attendance. They were safe so long as the teacher did not report excessive absence."

Hook adopted the progressive methods of teaching that was promoted by John Dewey. " But the most important cause of my success was my ability to motivate the students, to build on their interests, and to capture and hold their attention by dramatizing events in history. To do this I had to disregard the syllabus for the grade. Capitalizing on the boys' passion for baseball, I taught them percentage, so that they could determine the standing of the clubs and the batting averages of the players, as well as American geography. They learned a great deal about the colorful historical figures of the past and present.... I followed progressive methods, not out of principle but because they actually worked. I was unorthodox even in my untimely progressivism. There were some skills that could only be acquired by drill, and one couldn't always make a game of them. I was not above resorting to external rewards for persistence in drill exercises."

Sidney Hook taught at the College of the City of New York. He also studied for his Ph.D. degree at Columbia University under John Dewey. "He (John Dewey) was world famous when I first got to know him, but he didn't seem to know it. He was the soul of kindness and decency in all things to everyone, the only great man whose stature did not diminish as one came closer to him. In fact it was difficult to remain in his presence for long without feeling uncomfortable... He was too kind, kind to a fault... There was an air of abstraction about Dewey that made his sensitivity to others surprising. It was as if he had an intuitive sense of a person's authentic, unspoken need. Anyone who thought he was a softie, however, would be brought up short. He had the canniness of a Vermont farmer and a dry wit that was always signaled by a chuckle and a grin that would light up his face."

In 1929 Hook visited the Soviet Union: "Although I became aware of definite shortcomings and lacks in Soviet life, I was completely oblivious at the time to the systematic repressions that were then going on against noncommunist elements and altogether ignorant of the liquidation of the so-called kulaks that had already begun that summer. I was not even curious enough to probe and pry, possibly for fear of what I would discover. To be sure, most of the politically knowledgable persons I met were Communists of varying degrees of fanaticism. Although the deadly purges of the Communist ranks had not yet begun, I was aware that followers of Trotsky were having a hard time of it. Adolf Joffe's letter of suicide - he was a leading partisan of Trotsky - protesting his treatment and that of others at the hands of the Party bureaucracy had moved me deeply, and Trotsky's expulsion from the Soviet Union while I was in Germany was still fresh in my mind. What accounted for my failure to discover the truth and even to search for it with the zeal with which I would have pursued reports of gross injustice committed elsewhere? Several things. First, I had come to the Soviet Union with the faith of someone already committed to the Socialist ideal and convinced that the Soviet Union was genuinely dedicated to its realization. This conviction had been nurtured and strengthened by the Soviet Union's peace policy, its enlightened social legislation all along the line, and despite its doctrinal orthodoxy, which I never shared, its declared educational theory and practice."

Sidney Hook was an early member of the Socialist Party of America and a supporter of Norman Thomas. "At the time the Socialists were not short of revolutionary rhetoric, and their chief spokesman, Norman Thomas, towered head and shoulders intellectually above the mediocrities of the rival organization. The real reason was that, in attaching themselves to the organizations influenced by the Communist Party, they felt they were identifying with the Soviet Union - the country that was showing the world the face of the future: a planned society, in which, allegedly, there was no unemployment, no human want in consequence of the production of plenty, and in which, allegedly, the workers of arm and brain controlled their own destinies... The Socialists, it was claimed, lacked the verve and fire required for the total expropriation of the bourgeoisie, for the destruction of its state apparatus, and for the transformation of existing educational, legal, and political institutions from top to bottom."

Hook was disturbed by the events that were taking place in the Soviet Union. He no longer felt he could support the policies of Joseph Stalin. Hook now decided to join with other like-minded people to form the American Workers Party (AWP). Established in December, 1933, Abraham Muste became the leader of the party and other members included Louis Budenz, James Rorty, V.F. Calverton, George Schuyler, James Burnham, J. B. S. Hardman and Gerry Allard.

Hook later argued: "The American Workers Party (AWP) was organized as an authentic American party rooted in the American revolutionary tradition, prepared to meet the problems created by the breakdown of the capitalist economy, with a plan for a cooperative commonwealth expressed in a native idiom intelligible to blue collar and white collar workers, miners, sharecroppers, and farmers without the nationalist and chauvinist overtones that had accompanied local movements of protest in the past. It was a movement of intellectuals, most of whom had acquired an experience in the labor movement and an allegiance to the cause of labor long before the advent of the Depression."

Soon after its formation of the AWP, leaders of the Communist League of America (CLA), a group that supported the theories of Leon Trotsky, suggested a merger. Sidney Hook, James Burnham and J. B. S. Hardman were on the negotiating committee for the AWP, Max Shachtman, Martin Abern and Arne Swabeck, for the CLA. Hook later recalled: "At our very first meeting, it became clear to us that the Trotskyists could not conceive a situation in which the workers' democratic councils could overrule the Party or indeed one in which there would be plural working class parties. The meeting dissolved in intense disagreement." However, despite this poor beginning, the two groups merged in December 1934.