On this day on 1st January

On this day in 1785 the first issue of The Times is published. In 1785 John Walter's career as a Lloyd's underwriter in London was at an end. An increase in insurance claims arising from a hurricane in Jamaica had ruined his business. Close to bankruptcy, John Walter decided to look for a new form of business. While an underwriter at Lloyds he became aware of a new method of typesetting called logography. The inventor, Henry Johnson, claimed that this new method of typesetting was faster and more accurate because it allowed more than one letter to be set at a time. John Walter purchased Johnson's patent and decided to start a printing company.

John Walter came to the conclusion that he had to find a good way of publicizing his logography system. Eventually he came up with the idea of producing a daily advertising sheet. The first edition of the Daily Universal Register was published on 1st January, 1785. The newspaper was in competition with eight other daily newspapers in London. Like the other newspapers,it included parliamentary reports, foreign news and advertisements. John Walter made it clear in the first edition of the newspaper that he was primarily concerned with advertising revenue: "The Register, in its politics, will be of no party. Due attention should be paid to the interests of trade, which are so greatly promoted by advertisements."

After a couple of years John Walter had discovered that logography was not going to have the impact on the printing industry that he had initially thought when he started the Daily Universal Register . However, he was now convinced he could make a profit from newspapers. Especially when he was able to negotiate a secret deal where he was paid £300 a year to publish stories favourable to the government.

In 1788 John Walter decided to change the name and the style of his newspaper. Walter now started to produce a newspaper that appealed to a larger audience. This included stories of the latest scandals and gossip about famous people in London. Walter called his new paper The Times. One of these stories about the Prince of Wales resulted in Walter being fined £50 and sentenced to two years in Newgate Prison.

In January, 1803 John Walter's son, John Walter II, became the new proprietor of The Times. John Walter II decided he wanted to run a newspaper that was independent of government control. He began employing young journalist who supported political reform including Henry Crabbe Robinson, Charles Lamb, William Hazlitt and Thomas Barnes. The newspaper turned away from government minister's handouts and instead developed its own news-getting organisation.

John Walter II also introduced new technology into The Times. In 1817 he installed a steam-powered Koenig printing machine. This increased the speed that newspapers could be printed and by the end of the year, the newspaper was selling over 7,000 copies a day. In the same year that the newspaper obtained their steam-powered printing machine, Thomas Barnes became the new editor of the newspaper. Barnes was a strong advocate on independent reporting. In 1819 he published a several articles written by John Edward Taylor and John Tyas on the Peterloo Massacre. The Times criticised the way Lord Liverpool's government was dealing with those arguing for political reform.

After the massacre The Times began to argue for parliamentary reform. By 1830 the newspaper was constantly urging the Whig government to take action. The views of the newspaper and its editor, Thomas Barnes, had a great influence on public opinion. The government tax on newspapers meant that its price of 7d. made it too expensive for most people to buy. However, copies were available in reading rooms. In 1831 the Tory St. James's Chronicle claimed that "for every one copy of The Times that is purchased for the usual purposes, nine we venture to say are purchased to be lent to the wretched characters who, being miserable, look to political changes for an amelioration of their condition."

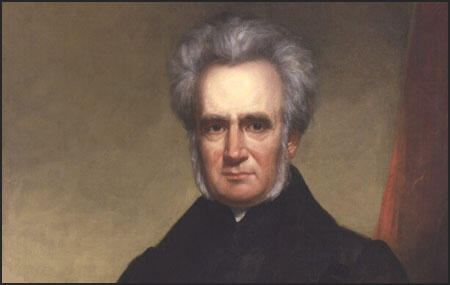

In Parliament the Tories complained about The Times campaign. In a debate that took place in the House of Commons on 7th March, 1832, Sir Robert Peel argued that the newspaper was the "principal and most powerful advocate of Reform" in Britain. After the 1832 Reform Act was passed The Times called it the "greatest event of modern history."

The Times also campaigned for the rights of trade unionists. In 1834 it became involved in what became known as the case of the Tolpuddle Martyrs. The Times condemned the decision to prosecute six farmworkers at Tolpuddle for "administering illegal oaths". The Times also supported the demands that the men should be reprieved after they were sentenced to transportation for seven years.

In 1834 a group of Whigs purchased control of the Morning Chronicle. Thomas Barnes disagreed with the way the Morning Chronicle gave "slavish support to the government". Barnes had talks with the leaders of the Conservative Party and after they had agreed that they would not attempt to interfere with reforms introduced by the Whigs such as the 1832 Reform Act and the Tithe Act, he agreed that the newspaper would became a supporter of Sir Robert Peel and his new government.

Thomas Barnes remained editor of The Times until his death on 7th May 1841. John Walter II made the surprising decision to invite the twenty-three year old John Delane to take over the job. Unlike Barnes, Delane rarely wrote for the paper. Delane held liberal views on most issues, but believed it was the role of a newspaper to be independent of political parties. In 1852 he wrote that it is the "duty of the journalist is the same as that of the historian - to seek truth above all things". However, he added that The Times "owes its first duty to the national interests" and that the "ends of government were absolutely identical with those of the press".

On this day in 1854 Francis Place died at the Hammersmith home of his two unmarried daughters. Place was born on 3rd November, 1771 in a debtor's prison in Drury Lane, where his father worked as a overseer. After a short period at school, Francis was apprenticed to a leather-breeches maker. At nineteen he married and settled into a small house near the Strand in London.

In 1793 Place became involved in a strike. Place was identified as one of the leaders of the strikers and after the dispute was over he found it impossible to find work as a leather-breeches maker. While out of work Place read about the trial of Thomas Hardy, John Horne Tooke, and John Thelwall, the three leaders of the the London Corresponding Society.

Place became convinced that the most important thing that working men needed was the vote and despite the persecution of its membership, he decided to join the group. With their leaders in prison, Place was offered and accepted the post of Chairman. He held the post until 1797 when he resigned in protest against the violent tactics of some members of the organisation.

While out of work Place educated himself by reading books on history, law and economics. In 1799 he opened his own tailor's shop at 16 Charing Cross Road. He used part of his premises as a library of radical books. People came to his shop to read and borrow books and pamphlets by people like Tom Paine and Joseph Priestley. Place's library soon became a meeting-place for reformers.

In 1807 Francis Place helped Sir Francis Burdett in his campaign to represent the Westminster constituency in the House of Commons. The two men became close friends and over the next couple of years Burdett introduced Place to other radical figures such as Robert Owen, Jeremy Bentham, and Joseph Hume.

Place also met Joseph Lancaster who convinced him of the importance of providing children with a non-sectarian education. Place played an active role in promoting Lancastrian schools as he believed it provided the best opportunity of "promoting the happiness of the rising generation". Place also hoped that these schools would help to eradicate what he believed was harming the progress of the working class: "drunkeness, lax morals, bad manners and over population".

Although Place fathered fifteen children, he was deeply concerned about the growth in the British population. In 1822 he wrote and published The Principles of Population. People were shocked to read in the book that Place advocated the use of contraceptives. Place was labelled a "bold bad man" and even some Radicals shunned him after the publication of this book.

Place also gave help to Radical politicians in the House of Commons. He collected data on issues such as the Combination Acts and parliamentary reform and then passed it on to Sir Francis Burdett, John Hobhouse and Joseph Hume so they could promote the cause in Parliament. Between 1822 and 1824 Place collected eight volumes of statistics that he believed indicated that the Combination Acts should be repealed. Place argued that the repeal of the Combination Acts would lead to the disappearance of trade unions. Place achieved victory in 1824 but he was shocked when he discovered that one of the consequences of this was a rapid growth in the trade union movement.

After the repeal of the Combination Acts in 1824 Place turned his attention to parliamentary reform. He played a prominent in the agitation that resulted in the 1832 Reform Act. Upset by the limited scope of the reform he joined with John Cleave, Henry Hetherington, and William Lovett to form the London Working Men's Association in 1836. Two years later he helped draft the People's Charter that instigated the Chartist movement.

Place was a Moral Force Chartist and argued strongly against the use of violence to obtain the vote. When Feargus O'Connor replaced William Lovett as the unofficial leader of the movement, Place ceased to be involved in Chartist activities. After 1840 Francis Place concentrated his energies on organizing the campaign against the Corn Laws. He also spent a considerable amount of time writing his autobiography and a history of the 1832 Reform Act.

On this day in 1857 after a long campaign by Caroline Norton, the Divorce and Matrimonial Causes Act comes into effect. Ernest Sackville Turner has argued that the "Common Law of England, in the early part of the 19th century the nineteenth century, granted a wife fewer rights than had been accorded to under the later Roman law, and hardly more than had been conceded to an African slave before emancipation... The husband... owned her body, her property, her savings, her personal jewels and her income, whether they lived together or separately." Turner goes on to point out, that the husband "could legally support his mistress on the earnings of his wife".

John Stuart Mill, the Radical MP for Westminster, was one of the few men who was willing to speak up for women: "She can acquire no property, but for the husband: the instant it becomes hers, even if by inheritance, it becomes ipso facto his... This is her legal state. And from this state she has no means to withdraw herself. If she leaves her husband she can take nothing with her, neither her children nor anything which is rightfully her own. If he chooses he can compel her to return by law, or by physical force; or he may content himself with seizing for his own use anything which she may earn or which may be given to her by her relations. It is only separation by a decree of a court of justice which entitles her to live apart without being forced back into the custody of an exasperated jailer."

In 1850 a Royal Commission had recommended that the government took a look into the workings of the Divorce Law. Robert Rolfe, 1st Baron Cranworth, took up the challenge and when he was appointed Lord Chancellor he began to draw up new legislation. Caroline Norton contacted Cranworth and requested that he included a clause that would ensure that wives could retain their own property after marriage.

Barbara Leigh Smith, the daughter of Benjamin Leigh Smith, the Radical MP for Norwich, joined the campaign, and published Brief Summary in Plain Language of the Most Important Laws Concerning Women (1854). It included the following passage: "A man and wife are one person in law; the wife loses all her rights as a single woman, and her existence is entirely absorbed in that of her husband. He is civilly responsible for her acts; she lives under his protection or cover, and her condition is called coverture. A woman's body belongs to her husband; she is in his custody, and he can enforce his right by a writ of habeas corpus."

As part of her campaign she published the pamphlet, English Laws for Women in the Nineteenth Century (1854). She explained that after years of experiencing violence from her husband she was unable to obtain a divorce: "I consulted whether a divorce 'by reason of cruelty' might not be pleaded for me; and I laid before my lawyers the many instances of violence, injustice, and ill-usage, of which the trial was but the crowning example. I was then told that no divorce I could obtain would break my marriage; that I could not plead cruelty which I had forgiven; that by returning to Mr Norton I had 'condoned' all I complained of. I learnt, too, the law as to my children – that the right was with the father; that neither my innocence nor his guilt could alter it; that not even his giving them into the hands of a mistress, would give me any claim to their custody. The eldest was but six years old, the second four, the youngest two and a half, when we were parted. I wrote, therefore, and petitioned the father and husband in whose power I was, for leave to see them – for leave to keep them, till they were a little older. Mr Norton's answer was, that I should not have them; that if I wanted to see them, I might have an interview with them at the chambers of his attorney."

Caroline Norton also wrote a letter to Queen Victoria complaining about the position of women in regards to divorce. "If her husband take proceedings for a divorce, she is not, in the first instance, allowed to defend herself. She has no means of proving the falsehood of his allegations... If an English wife be guilty of infidelity, her husband can divorce her so as to marry again; but she cannot divorce the husband, however profligate he may be. No law court can divorce in England. A special Act of Parliament annulling the marriage, is passed for each case. The House of Lords grants this almost as a matter of course to the husband, but not to the wife. In only four instances (two of which were cases of incest), has the wife obtained a divorce to marry again."

A group of women, including Barbara Leigh Smith, Emily Davies, Elizabeth Garrett and Dorothea Beale, organised a petition demanding equal legal rights with men. The petition signed by 26,000 men and women was submitted to Parliament. It was accepted by John Stuart Mill in the House of Commons and Lord Henry Brougham in the House of Lords. "The subject was almost entirely new to public consideration, and, as was natural, the feeling both in support of and in opposition to change was very strong. It would disrupt society, people said; it would destroy the home, and turn women into loathsome, self-assertive creatures no one could live with."

The proposed Marriage and Divorce Act was discussed at great length in 1857. William Ewart Gladstone, the future leader of the Liberal Party, was a strong opponent of the bill as he saw it as undermining the authority of the Church. He made seventy-three interventions against the bill, twenty-nine of them in the course of one protracted sitting. However, he was in a small minority and could only gain the support of a "few dozen votes".

In the House of Lords, John Bird Sumner, the Archbishop of Canterbury and Henry Phillpotts, Bishop of Exeter, both supported the measure and became law in January, 1858. Its main purpose was to transfer jurisdiction on divorce from Parliament and the ecclesiastical courts to a new tribunal. This simplified proceedings and radically lowered divorce costs, thereby making it available to a larger section of the population. Actions for "criminal conversations" were abolished.

The new law did not treat men and women on a equal basis. A man could divorce a woman if she was "guilty of adultery". However, the woman could only obtain a divorce if she could show that "her husband has been guilty of incestuous adultery, or of bigamy with adultery, or of rape, or of sodomy or bestiality, or of adultery coupled with such cruelty as without adultery would have entitled her to a divorce, or of adultery coupled with desertion, without reasonable excuse, for two years or upwards."

Four of the causes in the new act were based on Caroline Norton's experiences as a married woman. (Clause 21) A wife deserted by her husband might be protected if the possession of her earnings from any claim of her husband upon them. (Clause 24) The courts were able to direct payment of separate maintenance to a wife or to her trustee. (Clause 25) A wife was able to inherit and bequeath property like a single woman. (Clause 26) A wife separated from her husband was given the power of contract and suing, and being sued, in any civil proceeding.

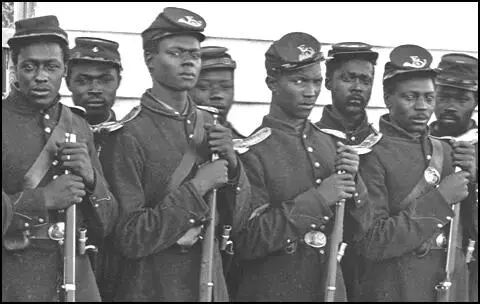

On this day in 1863, Abraham Lincoln gives his approval to the formation of black regiments. In January 1863 it was clear that state governors in the north could not raise enough troops for the Union Army. Lincoln had objected in May, 1862, when General David Hunter began enlisting black soldiers into the 1st South Carolina (African Descent) regiment. However, nothing was said when Hunter created two more black regiments in 1863.

John Andrew, the governor of Massachusetts, and a passionate opponent of slavery, began recruiting black soldiers and established the 5th Massachusetts (Colored) Cavalry Regiment and the 54th Massachusetts (Colored) and the 55th Massachusetts (Colored) Infantry Regiments. In all, six regiments of US Colored Cavalry, eleven regiments and four companies of US Colored Heavy Artillery, ten batteries of the US Colored Light Artillery, and 100 regiments and sixteen companies of US Colored Infantry were raised during the war. By the end of the conflict nearly 190,000 black soldiers and sailors had served in the Union forces.

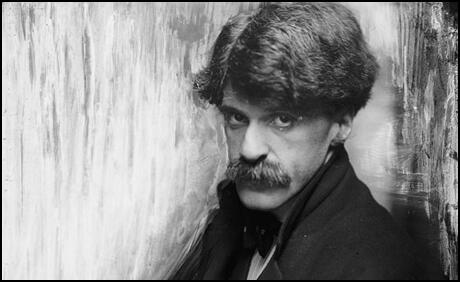

On this day in 1864 Alfred Stieglitz, the son of a wool merchant, was born in Hoboken, New Jersey. Stieglitz was sent to Europe to complete his education and was studying at the Berlin Polytechnic in 1883 when he discovered photography. He switched from mechanical engineering to photo-chemistry and began taking photographs. Stieglitz took a keen interest in the history of photography and over the next few years became a leading authority on the subject.

Stieglitz returned to the United States in 1890 where he obtained a reputation as a photographer who liked to overcome technical problems. This including taking the first successful photographs in snow and rain. He also experimented with flash powder so that he could take photographs at night.

Stieglitz was the most influential member of the Club for American Amateur Photographers. A member of the the Camera Club he joined with Clarence White, Edward Steichen, Alvin Langdon Coburn, and Gertrude Kasebier in 1902 to form the Photosecession Group.

Stieglitz also edited the quarterly Camera Work(1903-17) where he passionately advocated that photographs deserved to be judged as works of art. Stieglitz opened the Little Gallery on Fifth Avenue, to promote the work of photographers such as Paul Strand and Edward Steichen. He also ran the Intimate Gallery (1925-29) and An American Place (1929-46). Alfred Stieglitz died on 13th July, 1946.

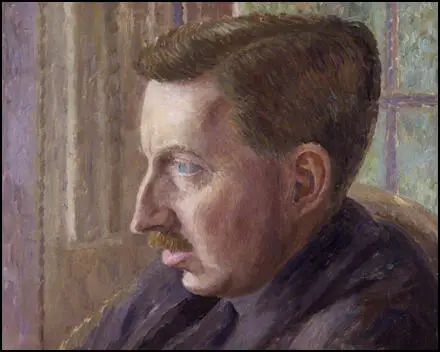

On this day in 1879 Edward Morgan Forster, the son of Edward Forster, an architect, and Marianne Thornton, was born in London. After an education at Tonbridge School and King's College, Cambridge, he spent a year travelling in Europe.

On his return to England in 1903, Forster taught Latin at the Working Men's College in London. He also joined with his friend, G. M. Trevelyan, to establish the Independent Review, a journal that supported the more progressive wing of the Liberal Party. Over the next few years the journal supported social reform and criticised the imperialistic foreign policies of the Conservative government.

Forster also became a member of the Bloomsbury Group that met and discussed literary and artistic issues. The group Virginia Woolf, Vanessa Bell, Clive Bell, John Maynard Keynes, Leonard Woolf, Lytton Strachey, David Garnett, Roger Fry and Duncan Grant.

Forster published his first novel, Where Angels Fear to Trend in 1905. This was followed by the Longest Journey (1907), A Room with a View (1908) and Howard's End (1910). Forster, also wrote Maurice, a novel about homosexuality, but decided to circulate it privately to prevent possible criticisms of his lifestyle.

As a pacifist Forster refused to fight in the First World War. Instead he worked in Alexandria for the International Red Cross. There was less disapproval of Forster's homosexuality in Alexandria and in 1917 he began living with an Egyptian tram conductor, Mohammed el Adl.

In 1919 Forster returned to England where he worked as literary editor for the left-wing newspaper, the Daily Herald. Two years later Forster moved to India were he worked as personal secretary for Maharajah of Dewas. These experiences resulted in his novel, Passage to India (1924).

When Forster returned to England he wrote essays and articles on a wide range of subjects, including a large number criticizing Nazism and Stalinism. A strong opponent of censorship, Forster gave his full support to the formation of the National Council of Civil Liberties and became its first president in 1934.

Forster did not write anymore novels after Passage to India but other books included the biography, Goldsworthy Lowes Dickinson (1934), a collection of essays, Two Cheers for Democracy (1951) the libretto for the opera, Billy Budd (1951), Aspects of the Novel (1953) and a book on India, The Hill of Devi (1953). Edward Morgan Forster died on 7th June 1970.

On this day in 1895 John Edgar Hoover was born in Washington. His father, Dickerson Hoover, was a printmaker, but he had a mental breakdown he spent his last eight years in Laurel Asylum.

The death of his father dramatically reduced the family income and Hoover had to leave school and seek employment. Hoover found work as a messenger boy in the Library of Congress, but highly ambitious, spent his evenings studying for a law degree at George Washington University.

After graduating in 1917, Hoover's uncle, a judge, helped him find work in the Justice Department. After only two years in the organisation, Alexander M. Palmer, the attorney general, made Hoover his special assistant. Hoover was given responsibility of heading a new section that had been formed to gather evidence on "revolutionary and ultra-revolutionary groups". Over the next couple of years Hoover had the task of organizing the arrest and deportation of suspected communists in America.

Hoover, influenced by his work at the Library of Congress, decided to create a massive card index of people with left-wing political views. Over the next few years 450,000 names were indexed and detailed biographical notes were written up on the 60,000 that Hoover considered the most dangerous. Hoover then advised Palmer to have these people rounded up and deported.

On 7th November, 1919, the second anniversary of the Russian Revolution, over 10,000 suspected communists and anarchists were arrested in twenty-three different cities. However, the vast majority of these people were American citizens and had to be eventually released. However, Hoover now had the names of hundreds of lawyers who were willing to represent radicals in court. These were now added to his growing list of names in his indexed database.

John Edgar Hoover decided he needed a high profile case to help his campaign against subversives. He selected Emma Goldman, as he had been particularly upset by her views on birth control, free love and religion. Goldman had also been imprisoned for two years for opposing America's involvement in the First World War. This was a subject that Hoover felt very strongly about, even though it was never willing to discuss how he had managed to avoid being drafted.

Hoover knew it would be a difficult task having Goldman deported. She had been living in the country for thirty-four years and both her father and husband were both citizens of the United States. In court Hoover argued that Goldman's speeches had inspired Leon Czolgosz to assassinate President William McKinley. Hoover won his case and Goldman, along with 247 other people, were deported to Russia.

Hoover's persecution of people with left-wing views had the desired effect and membership of the American Communist Party, estimated to have been 80,000 before the raids, fell to less that 6,000.

In 1921 Hoover was rewarded by being promoted to the post of assistant director of the Bureau of Investigation. The function of the FBI at that time was the investigation of violations of federal law and assisting the police and other criminal investigation agencies in the United States.

Hoover was appointed director of the Bureau of Investigation in 1924. The three years that he had spent in the organization had convinced Hoover that the organization needed to improve the quality of its staff. Great care was spent in recruiting and training agents. In 1926 Hoover established a fingerprint file that eventually became the largest in the world.

The power of the bureau was limited. Law enforcement was a stare activity, not a federal one. Hoover's agents were not allowed to carry guns, nor did they have the right to arrest suspects. Hoover complained about this situation and in 1935 Congress agreed to establish the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI). Agents were now armed and could act against crimes of violence throughout the United States.

John Edgar Hoover now set about establishing a world-class crime fighting organization. Innovations introduced by Hoover included the formation of a scientific crime-detention laboratory and the highly regarded FBI National Academy. Hoover appointed Clyde Tolson as Assistant Director of the FBI. In his book, The Secret Life of J. Edgar Hoover (1993), Anthony Summers claims that Hoover and Tolson became lovers. For the next forty years the two men were constant companions. In the FBI the couple were known as "J. Edna and Mother Tolson". Mafia boss, Meyer Lansky, obtained photographic evidence of Hoover's homosexuality and was able to use this to stop the FBI from looking too closely into his own criminal activities.

During the Spanish Civil War Hoover arranged for FBI agents to report on those Americans that fought for the Abraham Lincoln Battalion and George Washington Battalion. Hoover later wrote: "When a civil war broke out in that country in 1936, the Communists acted in line with the theory that the Soviet Union should be used as the base for the extension of Communist control over other countries. Soviet intervention in the Spanish civil war was twofold in nature. First, in response to directions from the Comintern, the international Communist movement organized International Brigades to fight in Spain. A typical unit was the Abraham Lincoln Brigade, organized in the United States... Many Communists throughout the world who answered the Comintern's call to fight in Spain were repaid subsequently by Soviet assistance in their attempts to seize power in their respective countries."

When the journalist, Ray Tucker, hinted at Hoover's homosexuality in an article for Collier's Magazine, he was investigated by the Federal Bureau of Investigation. Information about Tucker's private life was leaked to the media and when this became known, other journalists were frightened off from writing about this aspect of Hoover's life.

President Franklin D. Roosevelt enjoyed a good relationship with Hoover. Roosevelt's attorney general, Robert Jackson commented, "The two men liked and understood each other." Roosevelt asked Hoover to investigate Charles Lindbergh, one of the leaders of the American First Committee. He willingly did so for he had been upset by Lindbergh's critical comments about the failures of the FBI investigation into the kidnapping and murder of his infant son. He also provided detailed reports on isolationists such as Burton K. Wheeler, Gerald Nye and Hamilton Fish.

Roosevelt wrote to Hoover thanking him for this information. "I have intended writing you for some time to thank you for the many interesting and valuable reports that you have made to me regarding the fast moving situations of the last few months." Hoover replied on 14th June, 1940: "The letter is one of the most inspiring messages which I have ever been privileged to receive; and, indeed, I look upon it as rather a symbol of the principles for which our Nation stands. When the President of our country, bearing the weight of untold burdens, takes the time to express himself to one of his Bureau heads, there is implanted in the hearts of the recipients a renewed strength and vigor to carry on their tasks."

Hoover persuaded Franklin D. Roosevelt to give the FBI the task of investigating both foreign espionage in the United States. This included the collection of information on those with radical political beliefs. After Elizabeth Bentley, a former member of the American Communist Party, provided the FBI with information about a Soviet spy ring in 1945, Hoover became convinced that that their was a communist conspiracy to overthrow the United States government.

When checked, much of the information provided by Elizabeth Bentley was found to be untrue. However, by intimidating the people that Bentley had named, the FBI were able to obtain the information needed to convict Harry Gold, David Greenglass, Ethel Rosenberg and Julius Rosenberg of spying.

Hoover believed that several senior officials in the government were secret members of the Communist Party. Unhappy with the way Harry S. Truman, responded to this news, Hoover began leaking information about officials such as Alger Hiss to those politicians that shared his anti-communist views. This included Joseph McCarthy, John S. Wood, John Parnell Thomas, John Rankin and Richard Nixon. Hoover was a great supporter of the House of Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC), an organisation that relieved heavily on information provided by the FBI.

John Edgar Hoover was particularly concerned with the political influence that television and the cinema was having on the people of the United States. He encouraged the House of Un-American Activities Committee investigation into the entertainment industry and the decision by the major media networks to blacklist artists who were known to hold left of centre political views.

In June, 1950, three former FBI agents published Red Channels, a pamphlet listing the names of 151 writers, directors and performers who they claimed had been members of subversive organizations before the Second World War but had not so far been blacklisted. The names had been compiled from FBI files and a detailed analysis of the Daily Worker, a newspaper published by the American Communist Party.

A free copy of Red Channels was sent to those involved in employing people in the entertainment industry. All those people named in the pamphlet were blacklisted until they appeared in front of the House of Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC) and convinced its members they had completely renounced their radical past. By the late 1950s it was estimated that over 320 artists had been blacklisted and were unable to find work in television and the cinema.

Hoover became friends with Clint Murchison and Sid Richardson, became friends of J. Edgar Hoover, the head of the Federal Bureau of Investigation. It was the start of a long friendship. According to Anthony Summers, the author of The Secret Life of J. Edgar Hoover (1993): "Recognizing Edgar's influence as a national figure, the oilmen had started cultivating him in the late forties-inviting him to Texas as a houseguest, taking him on hunting expeditions. Edgar's relations with them were to go far beyond what was proper for a Director of the FBI."

Hoover and Clyde Tolson were regular visitors to Murchison's Del Charro Hotel in La Jolla, California. The three men would visit the local racetrack, Del Mar. Allan Witwer, the manager of the hotel at the time, later recalled: "It came to the end of the summer and Hoover had made no attempt to pay his bill. So I went to Murchison and asked him what he wanted me to do." Murchison told him to put it on his bill. Witwer estimates that over the next 18 summers Murchison's hospitality was worth nearly $300,000. Other visitors to the hotel included Richard Nixon, John Connally, Lyndon B. Johnson, Meyer Lansky, Santos Trafficante, Johnny Rosselli, Sam Giancana and Carlos Marcello.

In 1952 Hoover and Murchison worked together to mount a smear campaign against Adlai Stevenson, the Democratic Party candidate for the presidency. Hoover and Tolson, also invested heavily in Murchison's oil business. In 1954 Murchison joined forces with Sid Richardson and Robert Ralph Young to gain control of the New York Central Railroad. This involved buying 800,000 shares worth $20 million.

In 1953 Hoover asked one of his senior agents, Cartha DeLoach to join the American Legion to "straighten it out". According to the journalist, Sanford J. Ungar, he took the assignment so seriously that he became national vice-commander of the organization: "DeLoach became chairman of the Legion's national public relations commission in 1958 and in that position and in his other Legion offices over the years, he exercised a great deal of influence over the organization's internal policies as well as its public positions."

DeLoach became an important figure in Hoover's FBI. This included working closely with Lyndon B. Johnson. It was DeLoach who arranged with Johnson, who was the Senate majority leader, to push through legislation guaranteeing Hoover a salary for life. DeLoach later recalled: “There was political distrust between the two of them, but they both needed each other." However, he denied that the two men worked together to blackmail politicians. In his book, Hoover's FBI (1995), DeLoach argued: "The popular myth, fostered of late by would-be historians and sensationalists with their eyes on the bestseller list, has it that in his day J. Edgar Hoover all but ran Washington, using dirty tricks to intimidate congressmen and presidents, and phone taps, bugs, and informants to build secret files with which to blackmail lawmakers." According to DeLoach this was not true.

In 1958 Clint Murchison purchased the publishers, Henry Holt and Company. He told the New York Post: "Before I got them, they published some books that were badly pro-Communist. They had some bad people there.... We just cleared them all out and put some good men in. Sure there were casualties but now we've got a good operation." One of the first book's he published was by his old friend, J. Edgar Hoover. The book, Masters of Deceit: The Story of Communism in America (1958), was an account of the Communist menace and sold over 250,000 copies in hardcover and over 2,000,000 in paperback. It was on the best-seller lists for thirty-one weeks, three of them as the number one non-fiction choice.

William Sullivan was ordered to oversee the project, claimed that as many as eight agents worked full-time on the book for nearly six months. Curt Gentry, the author of J. Edgar Hoover: The Man and the Secrets (1991) points out Hoover claimed that he intended to give all royalties to the FBI Recreational Association (FBIRA). However, he claims that the "FBIRA was a slush fund, maintained for the use of Hoover, Tolson, and their key aides. It was also a money-laundering operation, so the director would not have to9 pay taxes on his book royalties." Gentry quotes Sullivan as saying that Hoover "put many thousands of dollars of that book.... into his own pocket, and so did Tolson."

Ronald Kessler, the author of The Bureau: The Secret History of the FBI (2002) DeLoach was involved in blackmailing Senator Carl T. Hayden, chair of the Senate Rules and Administration Committee, into following the instructions of Hoover. In April 1962, Roy L. Elson, Hayden's administrative assistant, questioned Hayden's decision to approve the $60 million cost of the FBI building. When he discovered what Elson was saying, DeLoach "hinted" that he had "information that was unflattering and detrimental to my marital situation... I was certainly vulnerable that way... There was more than one girl... The implication was there was information about my sex life... I interpreted it as attempted blackmail."

FBI Special Agent Arthur Murtagh also testified that Cartha DeLoach was involved in the blackmail of politicians on government committees. He claimed that DeLoach told him: "The other night, we picked up a siuation where this senator was seen drunk, in a hit-and-run accident, and some good-looking broad was with him. We got the information, reported it in a memorandum, and by noon the next day, the senator was aware that we had the information, and we never had trouble with him on appropriations since."

Hoover and the FBI carried out detailed investigations into any prominent person who he thought held dangerous political views. This included leaders of the civil rights movement and those opposed to the Vietnam War. At the same time Hoover virtual ignored organized crime and his investigations into political corruption was mainly used as a means of gaining control over politicians in powerful positions. In 1959 Hoover had 489 agents spying on communists but only 4 investigating the Mafia. As early as 1945 Harry S. Truman complained how Hoover and his agents were "dabbling in sex life scandals and plain blackmail when they should be catching criminals".

J. Edgar Hoover received information that President John F. Kennedy was having a relationship with Ellen Rometsch. In July 1963 Federal Bureau of Investigation agents questioned Romesch about her past. They came to the conclusion that she was probably a Soviet spy. Hoover actually leaked information to the journalist, Courtney Evans, that Romesch worked for Walter Ulbricht, the communist leader of East Germany. When Robert Kennedy was told about this information, he ordered her to be deported.

The FBI had discovered that there were several women at the Quorum Club who had been involved in relationships with leading politicians. This included both John F. Kennedy and Robert Kennedy. It was particularly worrying that this included Mariella Novotny and Suzy Chang. This was a problem because they both had connections to communist countries and had been named as part of the spy ring that had trapped John Profumo, the British war minister, a few months earlier. President Kennedy told J. Edgar Hoover that he "personally interested in having this story killed".

Hoover refused and leaked the information to Clark Mollenhoff. On 26th October he wrote an article in The Des Moines Register claiming that the FBI had "established that the beautiful brunette had been attending parties with congressional leaders and some prominent New Frontiersmen from the executive branch of Government... The possibility that her activity might be connected with espionage was of some concern, because of the high rank of her male companions". Mollenhoff claimed that John Williams "had obtained an account" of Rometsch's activity and planned to pass this information to the Senate Rules Committee.

John Edgar Hoover developed a close relationship with Lyndon B. Johnson. The two men shared information that they had on senior politicians. After the assassination of John F. Kennedy, Hoover helped Johnson to cover-up the assassination and the Bobby Baker scandal. In an interview Cartha DeLoach gave in 1991 he claimed: "Mr. Hoover was anxious to retain his job and to stay on as director. He knew that the best way for the F.B.I. to operate fully and to get some cooperation of the White House was for him to be cooperative with President Johnson... President Johnson, on the other hand, knew of Mr. Hoover’s image in the United States, particularly among the middle-of-the-road conservative elements, and knew it was vast. He knew of the potential strength of the F.B.I. - insofar as being of assistance to the government and the White House is concerned. As a result it was a marriage, not altogether of necessity, but it was a definite friendship caused by necessity.”

William Sullivan was the FBI's third-ranking official behind Hoover and Clyde A. Tolson. Sullivan was placed in charge of FBI's Division Five. This involved smearing leaders of left-wing organizations. Sullivan was a strong opponent of the leadership of Martin Luther King. In January, 1964, Sullivan sent a memo to Hoover: "It should be clear to all of us that King must, at some propitious point in the future, be revealed to the people of this country and to his Negro followers as being what he actually is - a fraud, demagogue and scoundrel. When the true facts concerning his activities are presented, such should be enough, if handled properly, to take him off his pedestal and to reduce him completely in influence." Sullivan's suggested replacement for King was Samuel Pierce, a conservative lawyer who was later to serve as Secretary of Housing under President Ronald Reagan.

FBI agent Arthur Murtagh was involved in the campaign against the civil rights movement: "He was brought up in a culture... in that society there was a real sense of belief, a religious belief, political belief, that there was no such thing as equality between blacks and whites, and that's the way he viewed them... Hoover did so many things to discredit the civil rights movement that I hardly know where to start. In the first place, he put about the same emphasis... much more of the facilities of the Bureau toward keeping the Klan... keeping the blacks in place and let the Klan run wild. He was friendly with people in the South, and ... when a situation came up, he would always make his decisions in favor of the local people."

William Sullivan disagreed with J. Edgar Hoover about the threat to national security posed by the American Communist Party and felt that the FBI was wasting too much money investigating this group. On 28th August, 1971, Sullivan sent Hoover a long letter pointing out their differences. Sullivan also suggested that Hoover should consider retirement. Hoover refused and it was Sullivan who had to leave the organization.

The FBI under John Edgar Hoover collected information on all America's leading politicians. Known as Hoover's secret files, this material was used to influence their actions. It was later claimed that Hoover used this incriminating material to make sure that the eight presidents that he served under, would be too frightened to sack him as director of the FBI. This strategy worked and Hoover was still in office when he died, aged seventy-seven, on 2nd May, 1972.

Clyde Tolson arranged for the destruction of all Hoover's private files. A senate report in 1976 was highly critical of Hoover and accused him of using the organization to harass political dissidents in the United States.

On this day in 1914 Noor Inayat Khan was born in the Soviet Union. Noor was the great-great-great-granddaughter of Tipu Sultan, the eighteenth-century Muslim ruler who died in the struggle against the British. Shortly after her birth in Moscow the family moved to England and later settled in France.

After studying music and medicine Noor became a writer. Her children stories were published in Figaro and a collection of traditional Indian stories, Twenty Jataka Tales, appeared in 1939.

On the outbreak of the Second World War she trained as a nurse with the Red Cross. In May 1940 France was invaded by the German Army. Just before the French government surrendered she escaped to England with her mother and sister.

In England she joined the Women's Auxiliary Air Force (WAAF) and trained as a wireless operator. While working at a Royal Air Force bomber station, her ability to speak French fluently brought her to the attention of the Special Operations Executive (SOE). After being interviewed at the War Office she agreed to become a British special agent.

Given the codename "Madeleine" she was flown to Le Mans with Diana Rowden and Cecily Lefort on 16th June 1943. She travelled to Paris where she joined the Prosper Network led by Francis Suttill. Soon after arriving a large number of members of the resistance group associated with Prosper were arrested by the Gestapo. Fearing that the group had been infiltrated by a German spy, she was instructed to return home. However, she declined, arguing that she was the only wireless operator left in the group.

Noor Inayat Khan continued to keep the Special Operations Executive in London informed by wireless what was going on in France. She also made attempts to rebuild the Prosper Network. However, it appears that the Gestapo already knew of her existence and were following her in an attempt to capture other members of the French Resistance.

After three and a half months in France Noor was arrested in October and taken to Gestapo Headquarters. She was interrogated and although she remained silent they discovered a book in her possession where she had recorded the messages she had been sending and receiving. The Gestapo were able to break her code and were able to send false information to the SOE in London and enabled them to capture three more secret agents landed in France.

Noor was taken to Nazi Germany where she was imprisoned at Karlsruhe. In the summer of 1944, Noor, and three other SOE agents, Yolande Beekman, Eliane Plewman and Madeleine Damerment, were moved to Dachau Concentration Camp. The four women were murdered by the Schutz Staffeinel (SS) on 12th September, 1944. In 1949 Noor Inayat Khan was posthumously awarded the George Cross.

On this day in 1919 Elsie Duval died of a heart attack. Duval became ill during the influenza epidemic andit is believed that her heart had been weakened by the treatment she received in prison.

Elsie Duval, daughter of Ernest Duval, was born on 19th February 1893. Her mother, Emily Duval, was a member of the Women Social & Political Union before joining the Women's Freedom League in 1907.

In January 1908 Elsie Duval was sentenced to one month's imprisonment after taking part in a demonstration at the home of Herbert Asquith. In 1911 Emily Duval left the WFL because it was not militant enough and rejoined the WSPU. Elsie's father, was also a supporter of women's suffrage and was a member of the Men's League For Women's Suffrage. Her brother, Victor Duval, was also imprisoned several times for taking part in demonstrations.

Elsie Duval joined the WSPU at the age of fifteen. She was at first too young to be involved in militant activity and was not arrested until 23rd November 1911 on a charge of obstructing the police. In March 1912 the WSPU organised a new campaign that involved the large-scale smashing of shop-windows. Elsie took part in this campaign and in July was sentenced to a month's imprisonment for breaking a window in Clapham. While in prison she was forcibly fed nine times.

Duval also took part in the WSPU's arson campaign. It is believed she was responsible for burning Sanderstead Station. She was arrested for "loitering with intent" on 3rd April 1913. She was sentenced to one month's imprisonment. After being released under the Cat and Mouse Act, she escaped with her boyfriend, Hugh Franklin, to Belgium and stayed in Brussels. She received a letter from Jessie Kenney that said: "Miss Pankhurst thinks it would be better for you to stay where you are for the time being and until you get stronger."

On 4th August, 1914, England declared war on Germany. Two days later the NUWSS announced that it was suspending all political activity until the war was over. The leadership of the WSPU began negotiating with the British government. On the 10th August the government announced it was releasing all suffragettes from prison. In return, the WSPU agreed to end their militant activities and help the war effort. Duval and Franklin now returned to England.

During the First World War she applied to work with Louisa Garrett Anderson and Flora Murray in a hospital in Claridge Hotel in Paris. The offer was rejected and on 28th September 1915 she married Hugh Franklin in the West London Synagogue. His father disinherited him for marrying out of the Jewish faith and never saw him again.

Elsie Duval became ill during the influenza epidemic and died of heart failure on 1st January 1919. It is believed that her heart had been weakened by the treatment she received in prison.

On this day in 1921 Mary Macarthur died. She developed cancer in 1920 and after two unsuccessful operations died at home, 42 Woodstock Road, Golders Green. She was cremated at Golders Green Crematorium three days later.

Mary Macarthur, the daughter of John Macarthur and Anne Martin, was born in Glasgow on 13th August 1880. The couple had six children, but only three survived, all of them girls. Mary attended the local school and after editing the school magazine, decided she wanted to become a full-time writer.

In 1895 the family opened a drapery business in Ayr and Mary was taken on as a book-keeper. John Macarthur was a supporter of the Conservative Party and an opponent of trade unions and sent his daughter to observe a meeting of the Shop Assistants' Union.

Mary was converted to the cause of trade unions by a speech made by John Turner about how badly some workers were being treated by their employers. Mary became secretary of the Ayr branch and at socialist meeting in the town, she met and fell in love with Will Anderson, an active member of the Independent Labour Party.

In 1902 Mary became friends with Margaret Bondfield who encouraged her to attend the union's national conference. She later recalled: "I had written to welcome her into the Union, but, when she came to meet me at the station, I was overcome with the sense of a great event. Here was genius, allied to boundless enthusiasm and leadership of a high order, coming to build our little Union into a more effective instrument." Mary was eventually elected to the union's national executive. Mary's political activities created conflict with her father who had a strong hatred for socialism. Anderson proposed marriage but Mary decided to pursue a career instead, and in 1903 moved to London where she became Secretary of the Women's Trade Union League.

As well as her trade union activities, Macarthur was an active member of the Independent Labour Party in London where she worked closely with two other Scots, James Keir Hardie and Ramsay MacDonald. Macarthur was involved in the Exhibition of Sweated Industries in 1905 and the formation of the Anti-Sweating League in 1906. The following year she founded The Woman Worker, a monthly newspaper for women trade unionists. Later it was transformed into a weekly with a circulation of about 20,000.

Angela V. John has argued: " Mary Macarthur is perhaps best known for founding the National Federation of Women Workers (NFWW) in 1906. She began as president, but then exchanged offices with Gertrude Tuckwell (1861–1951) to become general secretary. By the end of its first year the NFWW boasted seventeen branches in Scotland and England and about two thousand members. Mary Macarthur was especially concerned about the relationship between low wages and women's lack of organization."

Mary Macarthur was an inspirational figure and recruited many women into the movement. This included Dorothy Jewson and Susan Lawrence, who both went on to become Labour Party MPs. Active in the fight for the vote, she was totally opposed to those women in the NUWSS and the WSPU who were willing to accept the franchise being given to only certain categories of women. Macarthur believed that a limited franchise would disadvantage the working class and feared that it might act as a barrier against the granting of full adult suffrage. This made Macarthur unpopular with middle class suffragettes who saw limited suffrage as an important step in the struggle to win the vote.

Mary Macarthur sat on the executive of the Anti-Sweating League and gave evidence to the select committee on homework in 1908. Macarther also campaigned for a legal minimum wage. In the summer of 1911 she organized an estimated 2,000 women involved in twenty concurrent strikes in Bermondsey and other areas of London.

Will Anderson followed Macarthur down to London and the couple married on 21st September 1911. Their first child died at birth in 1913 but two years later a daughter, Anne Elizabeth, was born. Anderson was elected to the House of Commons to represent Sheffied Attercliffe in 1914 but was defeated in 1918. Macarthur also stood as a Labour candidate in Stourbridge, but like the others who opposed the First World War, she was defeated in the 1918 General Election.

Mary Macarthur was devastated when Will Anderson died in the 1919 influenza epidemic. She continued her work with the Women's Trade Union League and played an important role in transforming it into the Women's section of the Trade Union Congress.

On this day in 1922 suffragette and political activist, Minnie Lansbury, dies as a result of her imprisonment. Minnie Glassman, the daughter of Jewish coal merchant Isaac Glassman, was born in Stepney in 1889. She became a school teacher and was active in the campaign for women's suffrage.

In 1913, Sylvia Pankhurst, with the help of Millie Glassman, Julia Scurr, Keir Hardie and George Lansbury, established the East London Federation of Suffragettes (ELF). An organisation that combined socialism with a demand for women's suffrage it worked closely with the Independent Labour Party.

As June Hannam has pointed out: "The East London Federation of Suffragettes was successful in gaining support from working women and also from dock workers. The ELF organized suffrage demonstrations and its members carried out acts of militancy."

In 1914 Millie married Edgar Lansbury, the son of George Lansbury, the Labour Party MP for Bow & Bromley. Millie was a pacifist and opposed the First World War. In March 1916 Sylvia Pankhurst renamed the East London Federation of Suffragettes, the Workers' Suffrage Federation (WSF). The newspaper was renamed the Workers' Dreadnought and continued to campaign against the war and gave strong support to organizations such as the Non-Conscription Fellowship. In 1918 Millie was elected Assistant Secretary of the Workers' Socialist Federation.

In November 1919 Minnie Lansbury was elected to Poplar Council. The Labour Party had won 39 of the 42 council seats. In 1921 Poplar had a rateable value of £4m and 86,500 unemployed to support. Whereas other more prosperous councils could call on a rateable value of £15 to support only 4,800 jobless. George Lansbury proposed that the Council stop collecting the rates for outside, cross-London bodies. This was agreed and on 31st March 1921, Poplar Council set a rate of 4s 4d instead of 6s 10d. On 29th the Councillors were summoned to Court. They were told that they had to pay the rates or go to prison. At one meeting Millie said: "I wish the Government joy in its efforts to get this money from the people of Poplar. Poplar will pay its share of London's rates when Westminster, Kensington, and the City do the same."

On 28th August over 4,000 people held a demonstration at Tower Hill. The banner at the front of the march declared that "Popular Borough Councillors are still determined to go to prison to secure equalisation of rates for the poor Boroughs." The Councillors were arrested on 1st September. Five women Councillors, including Millie Lansbury, Julia Scurr and Susan Lawrence, were sent to Holloway Prison. Twenty-five men, including George Lansbury and John Scurr, went to Brixton Prison. On 21st September, public pressure led the government to release Nellie Cressall, who was six months pregnant. Julia Scurr reported that the "food was unfit for any human being... fish was given on Friday, they told us, that it was uneatable, in fact, it was in an advanced state of decomposition".

Instead of acting as a deterrent to other minded councils, several Metropolitan Borough Councils announced their attention to follow Poplar's example. The government led by Stanley Baldwin and the London County Council was forced to back down and on 12th October, the Councillors were set free. The Councillors issued a statement that said: "We leave prison as free men and women, pledged only to attend a conference with all parties concerned in the dispute with us about rates... We feel our imprisonment has been well worth while, and none of us would have done otherwise than we did. We have forced public attention on the question of London rates, and have materially assisted in forcing the Government to call Parliament to deal with unemployment."

While in Holloway Prison Minnie Lansbury developed pneumonia and she died on 1st January 1922. According to Janine Booth she had told friends " that imprisonment had weakened her physically, leaving her body unable to fight off the illness that killed her." Her father-in-law, George Lansbury said: "Minnie, in her 32 years, crammed double that number of years' work compared with what many of us are able to accomplish. Her glory lies in the fact that with all her gifts and talents one thought dominated her whole being night and day: How shall we help the poor, the weak, the fallen, weary and heavy-laden, to help themselves? When, a soldier like Minnie passes on, it only means their presence is withdrawn, their life and work remaining an inspiration and a call to us each to close the ranks and continue our march breast forward."

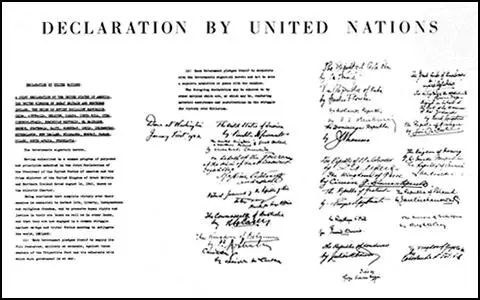

On this day in 1942, the Declaration by United Nations is published. President Franklin D. Roosevelt, supported by the representatives of 26 countries, published the Declaration by United Nations, a document that pledged their governments to continue fighting together against Nazi Germany and Japan during the Second World War.

This declaration was followed by a conference of Foreign Ministers in Moscow, in October, 1943 where discussions took place concerning a replacement for the discredited League of Nations.

Further talks took place at San Francisco between 15th April and 26th June, 1945. Delegates from fifty nations that had been at war with Germany, decided on the design and structure of this new organization. The conference drafted the United Nations Charter and it was signed on 26th June and ratified at the first session of the General Assembly of the United Nations in London on 24th October 1945.

The main differences between the League of Nations and the United Nations were the stronger executive powers assumed by the Security Council and the requirement that member states should make available armed forces to serve as peace-keepers or to repel an aggressor.

The Security Council had five permanent members, United States, the Soviet Union, China, France and Britain. Six other countries served two-year periods on the Council (this was increased to ten in 1965). Controversially, permanent members were given the power to veto decisions made by the Security Council. The other nations vigorously opposed the idea of the veto but it became clear that without such a favoured position the five major nations would not join the United Nations. The United States Senate ratified the United Nations treaty by a vote of 89 to 2 on 28th July, 1945.

On this day in 1969 Vera Holme died at 50 St Andrew's Drive, Glasgow, on 1st January 1969 of renal failure and arteriosclerosis.

Vera Holme, the daughter of Richard Holme, a timber merchant, was born in Birkdale, Lancashire, on 29th August 1881. According to Elizabeth Crawford, the author of The Suffragette Movement (1999), Holme was "an accomplished violinist and singer" and by 1908 she was a member of the chorus of the D'Oyly Carte Opera Company.

Later that year, Holme joined Elizabeth Robins, Kitty Marion, Winifred Mayo, Sime Seruya, Edith Craig, Inez Bensusan, Ellen Terry, Lillah McCarthy, Sybil Thorndike, Lena Ashwell, Christabel Marshall, Lily Langtry and Nina Boucicault to form the Actresses' Franchise League(AFL).

The first meeting of the AFL took place at the Criterion Restaurant at Piccadilly Circus. The AFL was open to anyone involved in the theatrical profession and its aim was to work for women's enfranchisement by educational methods, selling suffrage literature and staging propaganda plays.

In 1908 Holme also became an active member of the Women's Social and Political Union (WSPU). The following year she worked alongside Annie Kenney, Clara Codd and Elsie Howey in the West of England campaign. During this period she became a frequent visitor to Eagle House near Batheaston, the home of fellow WSPU member, Mary Blathwayt. Her father, Colonel Linley Blathwayt was sympathetic to the WSPU cause and he built a summer-house in the grounds of the estate that was called the "Suffragette Rest".

According to the historian, Martin Pugh, Holme was a lesbian. It seems that Eagle House became a place where these women met. Mary Blathwayt recorded in her diary that Annie Kenney had intimate relationships with at least ten members of the WSPU in her house. Blathwayt records in her diary that she slept with Annie in July 1908. Soon afterwards she illustrated jealousy with the comments that "Miss Browne is sleeping in Annie's room now." The diary suggests that Annie was sexually involved with both Christabel Pankhurst and Clara Codd. Blathwayt wrote on 7th September 1910 that "Miss Codd has come to stay, she is sleeping with Annie." Codd's autobiography, So Rich a Life (1951) confirms this account.

Emily Blathwayt recorded in her diary that Vera Holme "is a splendid woman and interested in all Linley's subjects and she took up Mary's violin and was very clever with it. She has a beautiful voice and we sang after washing up." However, Sylvia Pankhurst described Holme as "a noisy, explosive young person, frequently rebuked by her elders for lack of dignity."

A wealthy supporter of the WSPU donated money to buy Emmeline Pankhurst a motor car so that she could travel the country in comfort. In August 1909, Vera Holme was appointed as Pankhurst's chauffeur. The author of The Pankhursts (2001): "It is probable that Vera Holme had learnt to drive as a result of touring the provinces with a theatrical company; since driving tests had not been invented the chief requirement was a capacity to cope with the frequent mechanical breakdowns and to deal with horse traffic."

A wealthy supporter of the WSPU donated money to buy Emmeline Pankhurst a motor car so that she could travel the country in comfort. In August 1909, Vera Holme was appointed as Pankhurst's chauffeur. The author of The Pankhursts (2001): "It is probable that Vera Holme had learnt to drive as a result of touring the provinces with a theatrical company; since driving tests had not been invented the chief requirement was a capacity to cope with the frequent mechanical breakdowns and to deal with horse traffic."

In November 1909 Holme appeared as Hannah Snell in A Pageant of Great Women, a play written by Cicely Hamilton and performed by members of the Actresses' Franchise League. She remained active in the WSPU and on 9th May 1910 Colonel Linley Blathwayt planted a tree, a Juniperus Virginiana Aureomarginata, in her honour in his suffragette arboretum in a field adjacent to the house. 1911 she was sentenced to five days' imprisonment on a charge of stone throwing. horse traffic."

Eveline Haverfield died of pneumonia in 1920. In her will she left Vera Holme £50 a year for life. She went to live Margaret Greenless and Margaret Ker. She also spent a lot of time with Edith Craig, Clare Atwood and Christabel Marshall, who had formed a permanent ménage à trois at their home at The Priest's House, Tenterden. It was Craig who gave Vera Holme the nickname "Jacko". Other visitors included Radclyffe Hall, Una Troubridge, Vera Holme, Vita Sackville West and Virginia Woolf.

After the death of her mother, Ellen Terry in 1928, Edith Craig converted the barn in the grounds of her mother's house in Smallhythe Place, into a theatre. According to Katharine Cockin, the author of Edith Craig (1998): "In 1935 and 1936 the Barn Theatre hosted another anniversary: a tribute to Jacko. On 29 August 1935, the Grand performance in honour of Jacko's Birthday involved Edy, Chris and Tony in comical sketches."

Vera Holme died at 50 St Andrew's Drive, Glasgow, on 1st January 1969 of renal failure and arteriosclerosis.