On this day on 30th January

On this day in 1649 King Charles was executed. Parliament initially held Charles under house arrest at Holdenby House in Northamptonshire. Members of the House of Commons had different opinions about what to do with Charles. Some like Denzil Holles were willing to accept the return of the king to power on minimal terms, whereas Puritans like Oliver Cromwell demanded that Charles agree to firm limitations on his power before the army was disbanded. They also were committed to the idea that each congregation should be able to decide its own form of worship.

The New Model Army, frustrated by this lack of agreement, took Charles prisoner, and he was taken to Hampton Court Palace. Cromwell visited the king and proposed a deal. He would be willing to restore him as King and the Church of England as the official Church, if Charles and the Anglicans would agree to grant religious toleration. Charles rejected Cromwell's proposals and instead entered into a secret agreement with forces in Scotland who wanted to impose Presbyterianism.

Charles escaped from captivity on 11th November, 1647, and made contact with Colonel Robert Hammond, Parliamentary Governor of the Isle of Wight, whom he apparently believed to be sympathetic. Hammond, however, arrested Charles in Carisbrooke Castle. In the early months of 1648 rebellions broke out in several parts of the country. Oliver Cromwell put down the Welsh rising and Thomas Fairfax dealt with the rebels in Kent and Surrey.

In August 1648 Cromwell's parliamentary army defeated the Scots and once again Charles was taken prisoner. Parliament resumed negotiations with the King. The Presbyterians, the majority in the House of Commons, still hoped that Charles would save them from those advocating religious toleration and an extension of democracy. On 5th December, the House of Commons voted by 129 to 83 votes, to continue negotiations. The following day the New Model Army occupied London and Colonel Thomas Pride purged Parliament of MPs who favoured a negotiated settlement with the King.

General Henry Ireton demanded that Charles was put on trial. Cromwell had doubts about this and it was not until several weeks later that he told the House of Commons that "the providence of God hath cast this upon us". Once the decision had been made Cromwell "threw himself into it with the vigour he always showed when his mind was made up, when God had spoken".

In January 1649, Charles was charged with "waging war on Parliament." It was claimed that he was responsible for "all the murders, burnings, damages and mischiefs to the nation" in the English Civil War. The jury included members of Parliament, army officers and large landowners. Some of the 135 people chosen as jurors did not turn up for the trial. For example. General Thomas Fairfax, the leader of the Parliamentary Army, did not appear. When his name was called, a masked lady believed to be his wife, shouted out, "He has more wit than to be here."

This was the first time in English history that a king had been put on trial. Charles believed that he was God's representative on earth and therefore no court of law had any right to pass judgement on him. Charles therefore refused to defend himself against the charges put forward by Parliament. Charles pointed out that on 6th December 1648, the army had expelled several members of' Parliament. Therefore, Charles argued, Parliament had no legal authority to arrange his trial. The arguments about the courts legal authority to try Charles went on for several days. Eventually, on 27th January, Charles was given his last opportunity to defend himself against the charges. When he refused he was sentenced to death. His death warrant was signed by the fifty-nine jurors who were in attendance.

On the 30th January, 1649, Charles was taken to a scaffold built outside Whitehall Palace. Charles wore two shirts as he was worried that if he shivered in the cold people would think he was afraid of dying. He told his servant "were I to shake through cold, my enemies would attribute it to fear." Charles told the audience: "It is not my case alone, it is the freedom and liberty of the people of England; and do you pretend what you will, I stand more for their liberties. For, if power without law may make laws, may alter the fundamental laws of the kingdom, I do not know what subject he is in England that can be sure of his life, or anything that he calls his own."

Troopers on horseback kept the crowds some distance from the scaffold and it is unlikely that many people heard the speech that he made just before his head was cut off with an axe. The executioner then took up the head and announced, in traditional fashion, "Behold the head of a traitor!" At that moment, according to an eyewitness, "there was such a groan by the thousands then present, as I never heard before and desire I may never hear again."

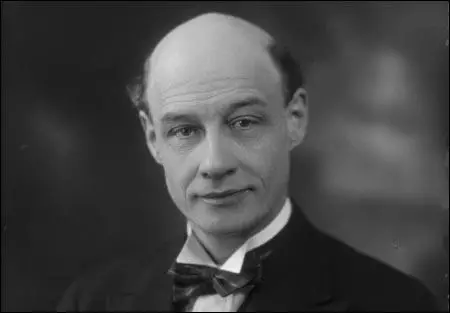

On this day in 1864 Helena Sickert, the daughter of the artist, Oswald Sickert, was born in 1864. Her mother, Eleanor Louisa Moravia Henry (1830–1922), was the illegitimate daughter of a professional dancer and a fellow of Trinity College. She had three brothers, of whom the eldest was Walter Sickert.

In 1868 the Sickerts moved to England and settled first in Bedford, and then in Notting Hill, where they became friends with William Morris, Johnson Forbes Robertson and Edward Burne-Jones.

At fourteen Helena went to Notting Hill High School. While at school she read, The Subjection of Women by John Stuart Mill. Deeply influenced by Mill's ideas, she rebelled against her parent's views on the role of women. She complained about the way she was treated by her mother. "A boy might be a person but not a girl. This was the ineradicable root of our differences. All my brothers had rights as persons; not I. Till I married (at the age of twenty four), she never, in her heart, conceded one personal right."

In 1882 Helena's father refused to pay the fees for her to attend Girton College. However, she had a sympathetic godmother who agreed to finance her studies. Her tutors included Henry Sidgwick, Alfred Marshall, and John Neville Keynes. She gained second-class honours and in 1885 she was appointed lecturer in psychology at Westfield College.

While at the University of Cambridge she met Frederick Tertius Swanwick, a lecturer in mathematics at Owens College . Although there was a thirteen years age difference, the couple married in 1888 and set up home in Manchester. There were no children of the marriage. Helena Swanwick became a close friend of C. P. Scott and his wife, Rachel Scott, over the next few years wrote articles and reviewed books for the Manchester Guardian.

Swanwick also did voluntary work in a girls' club, which brought her into contact with the Women's Trade Union League, the Women's Co-operative Guild, and the Independent Labour Party. During this period she met Emmeline Pankhurst and her daughters. In 1905 she joined the North of England Suffrage Society, which was affiliated to the National Union of Women's Suffrage Societies. Soon afterwards she read about how Christabel Pankhurst and Annie Kenney defied "the Liberal Stewards at Sir Edward Grey's meeting". She wrote that "my heart rose in support of their revolt. I sent them a subscription and, if I had not, for the moment, been suffering from an attack of influenza, I think I should have rushed into Manchester and enrolled myself with them. I am glad that this did not happen, for I should very soon have discovered differences so fundamental as to require me to break away again!"

in 1908 she "addressed one hundred and fifty meetings all over England and Scotland with an average attendance of six hundred persons." The following year she became editor of the NUWSS's weekly journal, The Common Cause. As a pacifist, Swanwick was a strong opponent of the Women's Social & Political Union. She also disapproved of what she believed was the anti-male stance taken by its leading members, Emmeline Pankhurst and Christabel Pankhurst.

When in 1912 Millicent Fawcett tried to persuade Swanwick to be less critical of the Women's Social & Political Union, she resigned her post as editor of The Common Cause. The following year she wrote a book where she was able to express her own views on the best way to achieve universal suffrage, The Future of the Women's Movement (1913).

In July 1914 the NUWSS argued that Asquith's government should do everything possible to avoid a European war. Two days after the British government declared war on Germany on 4th August 1914, Millicent Fawcett declared that it was suspending all political activity until the conflict was over. Although the NUWSS supported the war effort, it did not follow the WSPU strategy of becoming involved in persuading young men to join the armed forces.

Despite pressure from members of the NUWSS, Fawcett refused to argue against the First World War. Her biographer, Ray Strachey, argued: "She stood like a rock in their path, opposing herself with all the great weight of her personal popularity and prestige to their use of the machinery and name of the union." Swanwick resigned from the NUWSS over its policy on the war.

The day after war was declared, Charles Trevelyan, a member of Asquith's government who had resigned over this issue, began contacting friends about a new political organisation he intended to form to oppose the conflict. This included two pacifist members of the Liberal Party, Norman Angell and E. D. Morel, and Ramsay MacDonald, the leader of the Labour Party. A meeting was held and after considering names such as the Peoples' Emancipation Committee and the Peoples' Freedom League, they selected the Union of Democratic Control (UDC).

The founders of the UDC produced a manifesto and invited people to support it. Over the next few weeks several leading figures joined the organisation. This included Helena Swanwick, Mary Sheepshanks, J. A. Hobson, Charles Buxton, Frederick Pethick-Lawrence, Arnold Rowntree, Morgan Philips Price, George Cadbury, Fred Jowett, Tom Johnston, Philip Snowden, Ethel Snowden, David Kirkwood, William Anderson, Isabella Ford, H. H. Brailsford, Israel Zangwill, Bertrand Russell, Margaret Llewelyn Davies, Konni Zilliacus, Margaret Sackville and Olive Schreiner.

In January 1915 Mary Sheepshanks published an open Christmas letter to the women of Germany and Austria, signed by 100 British women pacifists. The signatories included Helena Swanwick, Emily Hobhouse, Margaret Bondfield, Maude Royden, Sylvia Pankhurst, Anne Cobden Sanderson, Eva Gore-Booth, Margaret Llewelyn Davies and Marion Phillips. It included the following: "Do not let us forget our very anguish unites us, that we are passing together through the same experiences of pain and grief. We pray you to believe that come what may we hold to our faith in peace and goodwill between nations."

At a Council meeting of the National Union of Women's Suffrage Societies held in February 1915, Millicent Fawcett attacked the peace efforts of people like Mary Sheepshanks. Fawcett argued that until the German armies had been driven out of France and Belgium: "I believe it is akin to treason to talk of peace." After a stormy executive meeting in Buxton all the officers of the NUWSS (except the Treasurer) and ten members of the National Executive resigned. This included Chrystal Macmillan, Kathleen Courtney, Catherine Marshall, Eleanor Rathbone and Maude Royden, the editor of the The Common Cause.

In April 1915, Aletta Jacobs, a suffragist in Holland, invited suffrage members all over the world to an International Congress of Women in the Hague. Some of the women who attended included Mary Sheepshanks, Jane Addams, Alice Hamilton, Grace Abbott, Emily Bach, Lida Gustava Heymann, Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence, Emily Hobhouse, Chrystal Macmillan, Rosika Schwimmer. At the conference the women formed the Women's International League for Peace and Freedom. Helena Swanwick was banned by the government for attending the conference but she soon joined the organisation and later that year became its chairman.

Her biographer, Jose Harris, has argued: "From 1915 to 1922 she was chairman of the Women's International League for Peace, which aimed to harness feminism to the peace movement; and throughout the First World War she campaigned for a negotiated peace and the establishment of an international peace-keeping organization. She was highly critical, however, of the terms under which the League of Nations was set up in 1919, partly because the league was permitted the use of force and economic sanctions, and partly because it was committed to supporting the Versailles settlement, which she regarded from the start as an unjust and unstable peace."

In 1924 Helena Swanwick became editor of Foreign Affairs, the journal of the Union of Democratic Control. She also wrote for the feminist journal, Time and Tide. She continued to campaign for an improvement in women's rights. In November 1927 she wrote: "The earlier struggles of women for emancipation necessarily take the form of beating at the closed doors of life. Till these are opened and we can see for ourselves what there is of knowledge and opportunity we cannot know how much we can put to good use. Many of these doors are still closed, but far more have been opened even in my lifetime than, as a girl, I should have ventured to hope. Our immediate and difficult task is to test all and reject what is not for us; to modify much and adapt it to our needs and natures. It is a commonplace to say that women are born into a world still largely man-made, it is their business to modify it till it becomes a human world as fit for full-sized women to live in as for full-sized men. It is my conviction that most men have not a notion how immensely better the world could be made for them, by the full co-operation of women. But that's another story."

Swanwick was active in the League of Nations Union and was a member of the British Empire delegation to the League of Nations in 1929. Swanwick wrote several books including an autobiography, I Have Been Young (1935).

Helena Swanwick, depressed by poor health and the growth of fascism in Europe, committed suicide on 16th November 1939 at her home in Maidenhead, after the outbreak of the Second World War.

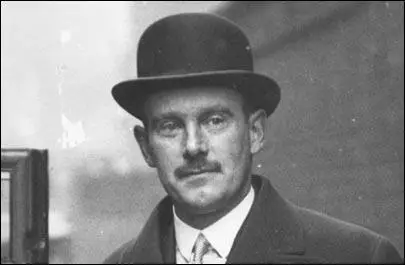

On this day in 1890 Stewart Menzies, the second son of John Graham Menzies (1861–1911) and his wife, Susannah West Wilson (1865–1943), was born in London on 30th January 1890. He entered Eton College in 1903, and there won prizes for languages that included the king's prize for German in 1907.

On leaving school, in 1909, he was commissioned in the Grenadier Guards. According to his biographer: "While in the army he acquired a love of horses and of hunting that remained with him for the rest of his life."

On the outbreak of the First World War he was sent to the Western Front with the British Expeditionary Force. He was awarded the Military Cross, after taking part in the major offensive in April 1915 at Ypres. After recovering from a gas attack he became a member of the staff of Sir Douglas Haig and worked in the counter-intelligence division at Montreuil. It was while working in this post he met Desmond Morton, Winston Churchill, Edward Louis Spears and Archibald Sinclair. As Gill Bennett, the author of Churchill's Man of Mystery (2009), has pointed out: "Menzies was also a close friend of Archibald Sinclair, who had introduced him to Churchill (Sinclair had become friendly with Churchill while both were learning to fly, and had served as Churchill 's second in command at Ploegsteert)."

Menzies married Lady Avice Ela Muriel Sackville, daughter of the eighth Earl Gilbert De La Warr and Muriel De Lar Warr on 29th November 1918. The marriage was not a success and he later married Pamela Thetis Beckett and she later gave birth to a daughter, Daphne.

In 1919 Menzies was appointed as head of the military division of the Secret Intelligence Service (SIS), also known as MI6. In the 1923 General Election, the Labour Party won 191 seats. Although the Conservatives had 258, Ramsay MacDonald agreed to head a minority government, and therefore became the first member of the party to become Prime Minister. As MacDonald had to rely on the support of the Liberal Party, he was unable to get any socialist legislation passed by the House of Commons. The only significant measure was the Wheatley Housing Act which began a building programme of 500,000 homes for rent to working-class families.

Stewart Menzies, like other members of establishment, was appalled by the idea of a Prime Minister who was a socialist. As Gill Bennett has pointed out: "It was not just the intelligence community, but more precisely the community of an elite - senior officials in government departments, men in "the City", men in politics, men who controlled the Press - which was narrow, interconnected (sometimes intermarried) and mutually supportive. Many of these men... had been to the same schools and universities, and belonged to the same clubs. Feeling themselves part of a special and closed community, they exchanged confidences secure in the knowledge, as they thought, that they were protected by that community from indiscretion."

In September 1924 the MI5 intercepted a letter signed by Grigory Zinoviev, chairman of the Comintern in the Soviet Union, and Arthur McManus, the British representative on the committee. In the letter British communists were urged to promote revolution through acts of sedition. Hugh Sinclair, provided "five very good reasons" why he believed the letter was genuine. However, one of these reasons, that the letter came "direct from an agent in Moscow for a long time in our service, and of proved reliability" was incorrect.

Vernon Kell, head of MI5 and Sir Basil Thomson head of Special Branch, were also convinced that the letter was genuine. Kell showed the letter to Ramsay MacDonald, the Labour Prime Minister. It was agreed that the letter should be kept secret but someone leaked news of the letter to the Times and the Daily Mail. The Zinoviev Letter was published in these newspapers four days before the 1924 General Election and contributed to the defeat of MacDonald and the Labour Party.

In a speech he made on 24th October, Ramsay MacDonald suggested he had been a victim of a political conspiracy: "I am also informed that the Conservative Headquarters had been spreading abroad for some days that... a mine was going to be sprung under our feet, and that the name of Zinoviev was to be associated with mine. Another Guy Fawkes - a new Gunpowder Plot... The letter might have originated anywhere. The staff of the Foreign Office up to the end of the week thought it was authentic... I have not seen the evidence yet. All I say is this, that it is a most suspicious circumstance that a certain newspaper and the headquarters of the Conservative Association seem to have had copies of it at the same time as the Foreign Office, and if that is true how can I avoid the suspicion - I will not say the conclusion - that the whole thing is a political plot?"

After the election it was claimed that two of MI5's agents, Sidney Reilly and Arthur Maundy Gregory, had forged the letter and that Major George Joseph Ball (1885-1961), a MI5 officer, leaked it to the press. In 1927 Ball went to work for the Conservative Central Office where he pioneered the idea of spin-doctoring. Later, Desmond Morton, who worked under Hugh Sinclair, at MI6, claimed that it was Stewart Menzies who sent the Zinoviev Letter to the Daily Mail. Menzies was promoted to the rank of colonel in 1932.

Hugh Sinclair, who had been suffering from cancer of the spleen, was taken into hospital in October 1939. Aware he was dying he sent a letter to William Ironside, the Chief of the Imperial General Staff: "I wish to place on record that, in my considered opinion, the most suitable individual, in every respect, to take my place, is Colonel Stewart Graham Menzies." This message was passed to the government and on the death of Sinclair on 4th November, 1939, Stewart Menzies was appointed as Director General of MI6.

His biographer, A. O. Blishen has pointed out: "Menzies was also responsible for the overall supervision of the Government Code and Cypher School (GCCS), whose greatest achievement in the war was the breaking, with considerable initial Polish and French help, of the German Enigma. This was an electro-mechanical enciphering and deciphering machine that was widely used by units of the German army, navy, and air force. German experts had rendered their machine so sophisticated that by the outbreak of the war they believed it safe even if captured. It was therefore used to communicate vital German war secrets. These began to be made available by GCCS by the end of 1940, and by the end of 1943 the school was decrypting as many as 40,000 naval and 50,000 army and air force messages a month."

Gill Bennett has argued that breaking the Enigma Code enabled Menzies to develop a very close relationship with Winston Churchill. "Stewart Menzies... welcomed the opportunity to ensure that Churchill got what he wanted. He was much less willing, however, to relinquish any control over his prime asset: the Enigma material supplied by the GC&CS codebreakers at Bletchley Park - Ultra, as it would later be called. Though still in its infancy in the summer of 1940, the source of intelligence, and in particular german Air Force (GAF) Enigma, played a valuable role both in giving warning of forthcoming air raids on Britain, and in providing details of GAF strengths and dispositions... It also laid the foundation for the closer relationship between the SIS Chief and the Prime Minister." Hugh Dalton, noted in his diary that Churchill considered Menzies "a wonderful fellow" and therefore... "we must not have quarrels" with him as he "has become so invulnerable".

Hugh Trevor-Roper, who worked with Menzies during the Second World War described him as "a bad judge of men" who "drew his personal advisers from a painfully limited social circle" and never "really understood the war in which he was engaged". William Cavendish-Bentinck, the chairman of the Joint Intelligence Sub-Committee, claimed that Menzies "was not a very strong man and not a very intelligent one" and that "he would not have held the job for more than a year if it had not been for" the work of Bletchley Park.

His second wife, Pamela Thetis Menzies, died in 1951. The following year he married Audrey Clara Lilian Chaplin. Menzies remained as Director General of MI6 until he was replaced by John Sinclair in July 1952.

Sir Stewart Menzies died in the King Edward VII Hospital for Officers, Beauchamp Place, London, on 29 May 1968.

On this day in 1915 John Profumo, the son of Albert Profumo, was born. The Profumo family made their fortune in insurance and by the outbreak of the First World War held a controlling interest in Provident Life.

Profumo was educated at Harrow and Brasenose College, Oxford, he became a member of the Conservative Party and by the age of 21 he was chairman of the Fulham Conservative Association. In May 1939 he was adopted as Conservative candidate for Kettering, but on the outbreak of the Second World War he joined the 1st Northamptonshire Yeomanry.

In 1940 there was an unexpected by-election at Kettering, and at the age of 25 he became the youngest MP in the House of Commons. However, the result caused a sensation as a Workers and Pensioners Anti-War candidate polled 27 per cent of the vote. On 8th May 1940 Profumo, along with 30 Conservative MPs, joined forces with the Labour Party to vote against the government's handling of Nazi Germany. As a result of this vote Neville Chamberlain was forced to resign and was replaced by Winston Churchill as prime minister.

Profumo had a distinguished military career, being mentioned in dispatches during the North Africa campaign. He served with Field Marshal Harold Alexander in Italy. He was later appointed Brigadier and Chief of Staff to the British Liaison Mission to General Douglas MacArthur in Japan. Profumo also landed in Normandy on D-Day with an armoured brigade, and took part in the fighting at Caen.

Profumo lost his seat in the 1945 General Election. He obtained a post at Conservative Central Office as the party's broadcasting adviser. Profumo was returned to the House of Commons as MP for Stratford-on-Avon in the 1950 General Election. Two years later he was appointed a junior minister at the Ministry of Transport and Civil Aviation.

In 1957 Profumo was appointed Parliamentary Under Secretary to the Colonies and subsequently Minister of State for Foreign Affairs. In 1960 Harold Macmillan appointed Profumo as his Secretary of State for War.

On 8th July 1961 Profumo met Christine Keeler, at a party at Cliveden. Profumo kept in contact with Keeler and they eventually began an affair. At the same time Keeler was also sleeping with Eugene Ivanov, a Soviet spy. According to Keeler: "Their (Ward and Hollis) plan was simple. I was to find out, through pillow talk, from Jack Profumo when nuclear warheads were being moved to Germany."

During this period she became involved with two black men, Lucky Gordon and John Edgecombe. The two men became jealous of each other and this resulted in Edgecombe slashing Gordon's face with a knife. On 14th December 1962, Edgecombe, fired a gun at Stephen Ward's Wimpole Mews flat, where Keeler had been visiting with Mandy Rice-Davies.

Two days after the shooting Christine Keeler contacted Michael Eddowes for legal advice about the Edgecombe case. During this meeting she told Eddowes "Stephen (Ward) asked me to ask Jack Profumo what date the Germans were to get the bomb." Eddowes then asked Ward about this matter. Keeler later recalled: "Stephen fed him the line he had prepared with Roger Hollis for such an eventuality: it was Eugene (Ivanov) who had asked me to find out about the bomb."

A few days later Keeler met John Lewis, a Labour Party MP and successful businessman at a Christmas party. Keeler later confessed: "I told him about Stephen asking me to get details about the bomb. I told him about Jack (Profumo). He told George Wigg, the powerful Labour MP with the ear of Harold Wilson. Wigg, who was Jack's opposite number in the Commons, started a Lewis-style dossier; it was the official start of the investigations and questions which would pull away the foundations of the Macmillan government."

A FBI document reveals that on 29th January, 1963, Thomas Corbally, an American businessman who was a close friend of Stephen Ward, told Alfred Wells, the secretary to David Bruce, the ambassador, that John Profumo was having a sexual relationship with Christine Keeler and Eugene Ivanov. The document also stated that Harold Macmillan had been informed about this scandal.

On 21st March, George Wigg asked Henry Brooke, the Home Secretary, in a debate on the John Vassall affair in the House of Commons, to deny rumours relating to Christine Keeler and the John Edgecombe case. Richard Crossman then commented that Paris Match magazine intended to publish a full account of Keeler's relationship with Profumo. Barbara Castle also asked questions if Keeler's disappearance had anything to do with Profumo.

The following day Profumo made a statement attacking the Labour Party MPs for making allegations about him under the protection of Parliamentary privilege, and after admitting that he knew Keeler he stated: "I have no connection with her disappearance. I have no idea where she is." He added that there was "no impropriety in their relationship" and that he would not hesitate to issue writs if anything to the contrary was written in the newspapers. As a result of this statement the newspapers decided not to print anything about Profumo and Keeler for fear of being sued for libel.

On 27th March, 1963, Henry Brooke summoned Roger Hollis, the head of MI5, and Joseph Simpson, the Commissioner of the Metropolitan Police, to a meeting in his office. Philip Knightley pointed out in An Affair of State (1987): "All these people are now dead and the only account of what took place is a semi-official one leaked in 1982 by MI5. According to this account, when Brooke tackled Hollis on the rumour that MI5 had been sending anonymous letters to Mrs Profumo, Hollis vigorously denied it."

Roger Hollis then told Henry Brooke that Christine Keeler had been having a sexual relationship with John Profumo. At the same time Keeler was believed to be having an affair with Eugene Ivanov, a Soviet spy. According to Keeler, Stephen Ward had asked her "to find out, through pillow talk, from Jack Profumo when nuclear warheads were being moved to Germany." Hollis added that "in any court case that might be brought against Ward over the accusation all the witnesses would be completely unreliable" and therefore he rejected the idea of using the Official Secrets Act against Ward.

Henry Brooke then asked the Police Commissioner's view on this. Joseph Simpson agreed with Roger Hollis about the unreliable witnesses but added that it might be possible to get a conviction against Ward with a charge of living off immoral earnings. However, he added, that given the evidence available, a conviction was unlikely. Despite this response, Brooke urged Simpson to carry out a full investigation into Ward's activities.

On 25th May, 1963, George Wigg once again raised the issue of Keeler, saying this was not an attack on Profumo's private life but a matter of national security. On 5th June, John Profumo resigned as War Minister. His statement said that he had lied to the House of Commons about his relationship with Christine Keeler. The next day the Daily Mirror said: "What the hell is going on in this country? All power corrupts and the Tories have been in power for nearly twelve years."

Some newspapers called for Harold Macmillan to resign as prime minister. This he refused to do but he did ask Lord Denning to investigate the security aspects of the Profumo affair. Some of the prostitutes who worked for Stephen Ward began to sell their stories to the national press. Mandy Rice-Davies told the Daily Sketch that Christine Keeler had sexual relationships with Profumo and Eugene Ivanov, an naval attaché at the Soviet embassy.

After leaving politics Profumo worked for Toynbee Hall and in 1975 Profumo was awarded the CBE for his charity work for the disadvantaged in the East End of London.

In 1995 he told a friend: "Since 1963, there have been unceasing publications, both written and spoken, relating to what you refer to in your letter as the Keeler interlude. The majority of these have increasingly contained deeply distressing inaccuracies, so I have resolved to refrain from any sort of personal comment, and I propose to continue thus." John Profumo died on 9th March, 2006.

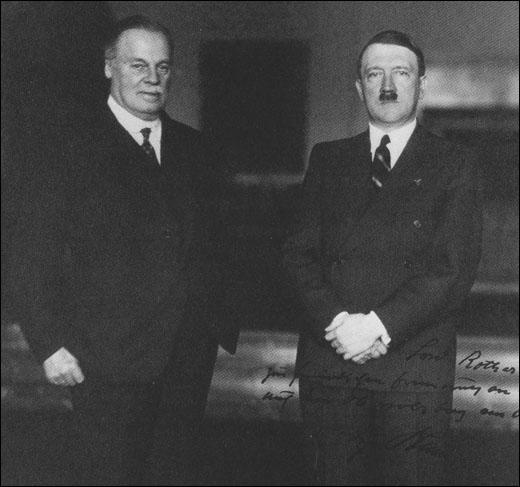

On this day in 1933, The Daily Mail welcomes Adolf Hitler becoming Chancellor of Germany. Harold Harmsworth (Lord Rothermere) the owner of the newspaper was a supporter of fascism. James Pool, the author of Who Financed Hitler: The Secret Funding of Hitler's Rise to Power (1979) points out: "Shortly after the Nazis' sweeping victory in the election of September 14, 1930, Rothermere went to Munich to have a long talk with Hitler, and ten days after the election wrote an article discussing the significance of the National Socialists' triumph. The article drew attention throughout England and the Continent because it urged acceptance of the Nazis as a bulwark against Communism... Rothermere continued to say that if it were not for the Nazis, the Communists might have gained the majority in the Reichstag."

Rothermere produced a series of articles supporting the new regime. In his publications he criticized "the old women of both sexes" who filled British newspapers with rabid reports of Nazi "excesses." Instead, the newspaper claimed, Hitler had saved Germany from "Israelites of international attachments" and the "minor misdeeds of individual Nazis will be submerged by the immense benefits that the new regime is already bestowing upon Germany."

According to Louis P. Lochner, Tycoons and Tyrant: German Industry from Hitler to Adenauer (1954) Lord Rothermere provided funds to Hitler via Ernst Hanfstaengel. When Hitler became Chancellor on 30th January 1933, Rothermere produced a series of articles acclaiming the new regime. The most famous of these was on the 10th July when he told readers that he "confidently expected" great things of the Nazi regime. He also criticised other newspapers for "its obsession with Nazi violence and racialism", and assured his readers that any such deeds would be "submerged by the immense benefits that the new regime is already bestowing on Germany." He pointed out that those criticising Hitler were on the left of the political spectrum: "I urge all British young men and women to study closely the progress of the Nazi regime in Germany. They must not be misled by the misrepresentations of its opponents. The most spiteful distracters of the Nazis are to be found in precisely the same sections of the British public and press as are most vehement in their praises of the Soviet regime in Russia."

George Ward Price, the Daily Mail's foreign correspondent developed a very close relationship with Adolf Hitler. According to the German historian, Hans-Adolf Jacobsen: "The famous special correspondent of the London Daily Mail, Ward Price, was welcomed to interviews in the Reich Chancellery in a more privileged way than all other foreign journalists, particularly when foreign countries had once more been brusqued by a decision of German foreign policy. His paper supported Hitler more strongly and more constantly than any other newspaper outside Germany."

Lord Rothermere also had several meetings with Adolf Hitler and argued that the Nazi leader desired peace. In one article written in March, 1934 he called for Hitler to be given back land in Africa that had been taken as a result of the Versailles Treaty. Hitler acknowledged this help by writing to Rothermere: "I should like to express the appreciation of countless Germans, who regard me as their spokesman, for the wise and beneficial public support which you have given to a policy that we all hope will contribute to the enduring pacification of Europe. Just as we are fanatically determined to defend ourselves against attack, so do we reject the idea of taking the initiative in bringing about a war. I am convinced that no one who fought in the front trenches during the world war, no matter in what European country, desires another conflict."

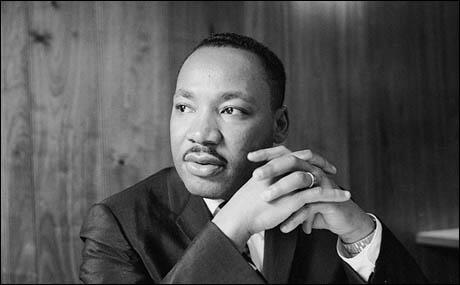

On this day in 1956 a bomb was thrown into the house of Martin Luther King. He later wrote in Stride Toward Freedom (1958): "I was immediately driven home. As we neared the scene I noticed hundreds of people with angry faces in front of the house. The policemen were trying, in their usual rough manner, to clear the streets, but they were ignored by the crowd.... In this atmosphere I walked out to the porch and asked the crowd to come to order. In less than a moment there was complete silence. Quietly I told them that I was all right and that my wife and baby were all right. "Now let's not become panicky," I continued. "If you have weapons, take them home; if you do not have them, please do not seek to get them. We cannot solve this problem through retaliatory violence. We must meet violence with nonviolence. Remember the words of Jesus: 'He who lives by the sword will perish by the sword.' " I then urged them to leave peacefully. "We must love our white brothers," I said, "no matter what they do to us. We must make them know that we love them. Jesus still cries out in words that echo across the centuries: 'Love your enemies; bless them that curse you; pray for them that despitefully use you.' This is what we must live by. We must meet hate with love. Remember," I ended, "if I am stopped, this movement will not stop, because God is with the movement. Go home with this glowing faith and this radiant assurance."

King had became becama target because of his involvement in the Montgomery Bus Boycott. King was pastor of the Dexter Avenue Baptist Church in Montgomery, Alabama. In Montgomery, like most towns in the Deep South, buses were segregated. On 1st December, 1955, Rosa Parks, a middle-aged tailor's assistant, who was tired after a hard day's work, refused to give up her seat to a white man.

After the arrest of Rosa Parks, King and his friends, Ralph David Abernathy, Edgar Nixon, and Bayard Rustin helped organize protests against bus segregation. It was decided that black people in Montgomery would refuse to use the buses until passengers were completely integrated. King was arrested and his house was fire-bombed. Others involved in the Montgomery Bus Boycott also suffered from harassment and intimidation, but the protest continued.

For thirteen months the 17,000 black people in Montgomery walked to work or obtained lifts from the small car-owning black population of the city. Eventually, the loss of revenue and a decision by the Supreme Court forced the Montgomery Bus Company to accept integration. and the boycott came to an end on 20th December, 1956.

On this day in 1959 John Smith Clarke, the Labour MP for Maryhill, died. Clarke, the thirteenth of fourteen children, was born in Scotland in 1885. His father worked in a circus and Clarke spent much of his early life living in gypsy encampments. After receiving little schooling he joined the circus as a horse bareback rider. At the age of seventeen he was working as a lion tamer. According to Gordon Munro: "He received the first of many injuries a few days later when a hurt lion attacked him when he entered the cage to help it."

In 1902 several political activists left the Social Democratic Federation (SDF), an organization led by H.L. Hyndman, to form the Glasgow Socialist Society. Eventually, most of the members of the SDF in Scotland joined this new group. In August 1903 it was renamed the Socialist Labour Party (SLP). The organization that had been inspired by the writings of Daniel De Leon, the man who helped establish the International Workers of the World (IWW) and the Socialist Labor Party in the United States. Clarke, who had been converted to socialism, joined the SLP. Leaders of the group included Willie Paul, Jack Murphy, Arthur McManus, Neil MacLean, James Connally, John MacLean and Tom Bell.

Clarke eventually became joint editor of the SLP journal, The Socialist, with Willie Paul, Tom Bell and Arthur McManus. In 1906 he began to organize the transport of weapons to revolutionary socialists in Russia. The operation lasted until the discovery of a cache at Blyth in Northumberland.

In 1910 Clarke moved to Edinburgh where he became editor of The Reform Journal. He also worked as a private secretary of the author Jane Clapperton (1832-1914).

John Clarke was opposed to Britain's involvement in the First World War. The historian, Nicola Rippon, has argued that "Clarke was not a pacifist, believing that the only armed struggle should be between the world's working classes and their capitalist employers."

In February 1916 the Clyde Workers' Committee became involved in a dispute at Beardmores Munitions Works in Parkhead. The government claimed that the strike was a ploy by the CWC to prevent the manufacture of munitions and therefore to harm the war effort. On 25th March, Arthur McManus, David Kirkwood, Willie Gallacher and other members of the CWC were arrested by the authorities under the Defence of the Realm Act. Sir Frederick Smith was the prosecutor. Tom Bell argued that: "It is doubtful if a more spiteful, hateful enemy of the workers ever existed... he threatened to send them to the front to be shot." The men were eventually court-martialled and sentenced to be deported from Glasgow to Edinburgh. The men lived with John Clarke until they could find other accommodation.

Over 3,000,000 men volunteered to serve in the British Armed Forces during the first two years of the war. Due to heavy losses at the Western Front the government decided to introduce conscription (compulsory enrollment) by passing the Military Service Act. The No-Conscription Fellowship (NCF) mounted a vigorous campaign against the punishment and imprisonment of conscientious objectors. About 16,000 men refused to fight. Most of these men were pacifists, who believed that even during wartime it was wrong to kill another human being.

Clarke joined Alice Wheeldon, Willie Paul and Arthur McManus, in establishing a network in Derby to help those conscientious objectors on the run or in jail. This included Alice's son, William Wheeldon, who was secretly living with his sister, Winnie Mason, in Southampton. According to Nicola Rippon Clarke "spent most of the war hiding in Mr Turner's farm at Arleston, now part of Sinfin on the southern outskirts of the town."

It was clear that the police intended to smash the peace movement that included Clarke and his left-wing friends. On 27th December 1916, Alex Gordon arrived at the house of Alice Wheeldon claiming to be a conscientious objectors on the run from the police. Alice arranged for him to spend the night at the home of Lydia Robinson. a couple of days later Gordon returned to Alice's home with Herbert Booth, another man who he said was a member of the anti-war movement. In fact, both Gordon and Booth were undercover agents working for MI5 via the Ministry of Munitions. According to Alice, Gordon and Booth both told her that dogs now guarded the camps in which conscientious objectors were held; and that they had suggested to her that poison would be necessary to eliminate the animals, in order that the men could escape.

Alice Wheeldon agreed to ask her son-in-law, Alfred Mason, who was a chemist in Southampton, to obtain the poison, as long as Gordon helped her with her plan to get her son to the United States: "Being a businesswoman I made a bargain with him (Gordon) that if I could assist him in getting his friends from a concentration camp by getting rid of the dogs, he would, in his turn, see to the three boys, my son, Mason and a young man named MacDonald, whom I have kept, get away."

On 31st January 1917, Alice Wheeldon, Hettie Wheeldon, Winnie Mason and Alfred Mason were arrested and charged with plotting to murder the British Prime Minister David Lloyd George and Arthur Henderson, the leader of the Labour Party. Their trial began three months later. Saiyid Haidan Riza argued that this was the first trial in English legal history to rely on the evidence of a secret agent. As Nicola Rippon pointed out in her book, The Plot to Kill Lloyd George (2009): "Riza declared that much of the weight of evidence against his clients was based on the words and actions of a man who had not even stood before the court to face examination." Riza argued: "I challenge the prosecution to produce Gordon. I demand that the prosecution shall produce him, so that he may be subjected to cross-examination. It is only in those parts of the world where secret agents are introduced that the most atrocious crimes are committed. I say that Gordon ought to be produced in the interest of public safety. If this method of the prosecution goes unchallenged, it augurs ill for England."

The judge disagreed with the objection to the use of secret agents. "Without them it would be impossible to detect crimes of this kind." However, he admitted that if the jury did not believe the evidence of Herbert Booth, then the case "to a large extent fails". Apparently, the jury did believe the testimony of Booth and after less than half-an-hour of deliberation, they found Alice Wheeldon, Winnie Mason and Alfred Mason guilty of conspiracy to murder. Alice was sentenced to ten years in prison. Alfred got seven years whereas Winnie received "five years' penal servitude."

Alice Wheeldon was sent to Aylesbury Prison where she began a campaign of non-cooperation with intermittent hunger strikes. One of the doctors at the prison reported that many prisoners were genuinely frightened of Alice who seemed to "have a devil" within her. However, the same doctor reported that she also had many admirers and had converted several prisoners to her revolutionary political ideas.

On 29th December 1917 David Lloyd George sent a message to the Home Office that he had "received several applications on behalf of Mrs Wheeldon, and that he thought on no account should she be allowed to die in prison." Herbert Samuel was reluctant to take action but according to the official papers: "He (Lloyd George) evidently felt that, from the point of view of the government, and in view especially of the fact that he was the person whom she conspired to murder, it was very undesirable that she should die in prison." Two days later she was released from Holloway Prison.

Alice Wheeldon's health never recovered from her time in prison. She died of influenza on 21st February 1919. At Alice's funeral, John Clarke made a speech that included the following: "She was a socialist and was enemy, particularly, of the deepest incarnation of inhumanity at present in Great Britain - that spirit which is incarnated in the person whose name I shall not insult the dead by mentioning. He was the one, who in the midst of high affairs of State, stepped out of his way to pursue a poor obscure family into the dungeon and into the grave... We are giving to the eternal keeping of Mother Earth, the mortal dust of a poor and innocent victim of a judicial murder."

In 1919 John Smith Clarke joined forces with Albert Young and Tom Anderson to publish a pamphlet entitled The Red Army - Revolutionary Poems. The following year he travelled to Moscow to attend the Communist International with William Gallacher as a delegate from the Clyde Workers' Committee. He met Lenin and other Bolshevik leaders but was not impressed by their style of government.

In April 1920 Tom Bell, Willie Gallacher, Arthur McManus, Harry Pollitt, Rajani Palme Dutt, Helen Crawfurd, A. J. Cook, Albert Inkpin, Arthur Horner, J. T. Murphy, John R. Campbell, Bob Stewart, Robin Page Arnot and Willie Paul joined forces to establish the Communist Party of Great Britain (CPGB). McManus was elected as the party's first chairman and Bell and Pollitt became the party's first full-time workers. John Clarke, refused to accept the power of the Bolsheviks in the formation of policy, and did not join the CPGB.

Clarke now became active in the Independent Labour Party (ILP) where he developed a close relationship with James Maxton. In 1928 Clarke published Marxism and History. Clarke became a councillor in Glasgow and in 1929 he was elected as MP for Maryhill in 1929. In theGeneral Election the Labour Party won 288 seats, making it the largest party in the House of Commons. Ramsay MacDonald became Prime Minister again, but as before, he still had to rely on the support of the Liberals to hold onto power.

The election of the Labour Government coincided with an economic depression and Ramsay MacDonald was faced with the problem of growing unemployment. MacDonald asked Sir George May, to form a committee to look into Britain's economic problem. When the May Committee produced its report in July, 1931, it suggested that the government should reduce its expenditure by £97,000,000, including a £67,000,000 cut in unemployment benefits. MacDonald, and his Chancellor of the Exchequer, Philip Snowden, accepted the report but when the matter was discussed by the Cabinet, the majority voted against the measures suggested by May.

MacDonald was angry that his Cabinet had voted against him and decided to resign. When he saw George V that night, he was persuaded to head a new coalition government that would include Conservative and Liberal leaders as well as Labour ministers. Most of the Labour Cabinet totally rejected the idea and only three, Philip Snowden, Jimmy Thomas and John Sankey agreed to join the new government.

Ramsay MacDonald was determined to continue and his National Government introduced the measures that had been rejected by the previous Labour Cabinet. Labour MPs were furious with what had happened and MacDonald was expelled from the Labour Party.

In October, MacDonald called an election. The 1931 General Election was a disaster for the Labour Party with only 46 members winning their seats. Clarke also lost his seat in Maryhill. MacDonald, now had 556 pro-National Government MPs and had no difficulty pursuing the policies suggested by Sir George May. However, disowned by his own party, he was now a prisoner of the Conservative Party, and in 1935 he was gently eased from power.

John Clarke returned to journalism and in 1936 his book An Encyclopaedia of Glasgow was published. As Gordon Munro has pointed out: "This contained items on the streets, buildings and historical places of the city which he served as a councillor for 15 years and in which he remained for the rest of his life."

A second edition of his earlier book Marxism and History was to be published by the National Council of Labour Colleges but his refusal to remove Leon Trotsky and Nikolay Bukharin from his original bibliography as demanded by leaders of the Communist Party of Great Britain meant that it was never published.

On this day in 1961 journalist Dorothy Thompson died in Lisbon, Portugal.

Dorothy Thompson, the daughter of Peter Thompson, a Methodist preacher, was born in Lancaster, New York, on 9th July, 1893. According to her biographer, Marion K. Sanders, when Dorothy was eight her mother died from blood poisoning after a bungled abortion performed by Dorothy's maternal grandmother."

Dorothy rebelled after her mother's death and her father's remarriage and she was sent to Chicago to live with her aunt. While studying politics and economics at Syracuse University she became a suffragist and was involved in the campaign to obtain the vote for women. After the First World War Thompson went to Europe to become a freelance writer.

In 1920 she persuaded the International News Service to let her cover a Zionist conference in Vienna. This work resulted in her being employed as a European correspondent for the Philadelphia Public Ledger. Later she acquired a similar post with the New York Post and in 1925 she was appointed as head of its Berlin bureau in Germany.

During this period she became friends with Raymond Gram Swing and John Gunther while working in Germany. Ken Cuthbertson, the author of Inside: The Biography of John Gunther (1992), has pointed out: "Thompson, who was taken with John Gunther, befriended him both as a young man and a pupil. Theirs was an intimate, albeit platonic (as far as is known), relationship which endured through good times and bad."

When she moved to Moscow in 1926 she became friends with fellow journalists, Hubert Knickerbocker, Walter Duranty, Louis Fischer, Vincent Sheean and William Henry Chamberlin. According to Sally J. Taylor, the author of Stalin's Apologist: Walter Duranty (1990): "Her presence in Moscow was the occasion for a good deal of socializing, which included meeting other reporters in the Soviet capital." Thompson met Sinclair Lewis at one of Duranty's parties. Taylor points out: "Lewis and his wife were the guests of honor at a dinner given at Duranty's apartment. Always known for his outrageous behaviour. Lewis discoursed wisely on this occasion, did a brilliant reading of his own work, and then, dead drunk, fell asleep on Duranty's couch. Finally, not knowing what else to do, everybody just went home. Duranty always held it against Lewis, believing that Lewis had behaved deplorably."

Dorothy Thompson met Lewis again in Berlin in June, 1927, when she went to tea with Gustav Stresemann. The following month she invited Lewis to her thirty-fourth birthday party. Susan Hertog, the author of Dangerous Ambition (2011) has pointed out: "Lewis, newly arrived from Paris, was in the midst of a drunken sprawl through Europe in search of distraction and oblivion. His wife, Grace Hegger, was in love with another man, and his newly published novel, Elmer Gantry, an expose of orgiastic moral corroption among the clergy, had been targeted by the church... It wasn't Lewis's literary reputation that intrigued Dorothy, although that might have sufficed; it was his ineffable sadness, and what she would call the Christ-like weight of his visceral suffering."

On 14th May 1928 Thompson married Sinclair Lewis. After interviewing Adolf Hitler in 1931 she wrote about the dangers of him winning power in Germany. A strong opponent of Hitler and his government, in 1934 Thompson became the first American correspondent to be expelled from Nazi Germany. A fellow journalist, Raymond Gram Swing, compared her writing with Freda Kirchwey: "I wish to say that she (Kirchwey) was one of the best and most likable journalists with whom I ever worked. I am tempted to call her the best woman journalist I ever encountered, but hesitate to rank her ahead of Dorothy Thompson, who was a better writer."

On her return to the United States Thompson joined the New York Tribune and in 1936 began writing a newspaper column, On the Record. The following year she began broadcasting for the NBC. Thompson also wrote for the Ladies' Home Journal and developed such a large following that Time Magazine called her the second most popular woman in America, after Eleanor Roosevelt. Books by Thompson included New Russia, (1928), I Saw Hitler! (1932), Anarchy or Organization (1938) and Let the Record Speak (1939).

Jennet Conant, the author of The Irregulars: Roald Dahl and the British Spy Ring in Wartime Washington (2008) argues that Ernest Cuneo, who worked for British Security Coordination, was "empowered to feed select British intelligence items about Nazi sympathizers and subversives" to friendly journalists such as Thompson, Walter Winchell, Drew Pearson, Walter Lippmann, Raymond Gram Swing, Edward Murrow, Vincent Sheean, Eric Sevareid, Edmond Taylor, Rex Stout, Edgar Ansel Mowrer and Whitelaw Reid, who "were stealth operatives in their campaign against Britain's enemies in America".

Thomas E. Mahl, the author of Desperate Deception: British Covert Operations in the United States, 1939-44 (1998) has argued: "During this period... Dorothy Thompson exhibited an amazing to reflect the British propaganda line of the day. This is one of the few useful conclusions to be gained from reading the hundreds of pages in her FBI file. Thompson's diary, kept for only a dozen entries in early 1942, also illustrates her close ties to the intelligence community."

Thompson lost her job with the New York Tribune after endorsing Franklin D. Roosevelt for a third term in 1944. She published The Courage to be Happy in 1957.

On this day in 1968 the Tet Offensive launched by the National Liberation Front. In September, 1967, the NLF launched a series of attacks on American garrisons. General William Westmoreland, the commander of US troops in Vietnam, was delighted. Now at last the NLF was engaging in open combat. At the end of 1967, Westmoreland was able to report that the NLF had lost 90,000 men. He told President Lyndon B. Johnson that the NLF would be unable to replace such numbers and that the end of the war was in sight.

Every year on the last day of January, the Vietnamese paid tribute to dead ancestors. In 1968, unknown to the Americans, the NLF celebrated the Tet New Year festival two days early. For on the evening of 31st January, 1968, 70,000 members of the NLF launched a surprise attack on more than a hundred cities and towns in Vietnam. It was now clear that the purpose of the attacks on the US garrisons in September had been to draw out troops from the cities.

The NLF even attacked the US Embassy in Saigon. Although they managed to enter the Embassy grounds and kill five US marines, the NLF was unable to take the building. However, they had more success with Saigon's main radio station. They captured the building and although they only held it for a few hours, the event shocked the self-confidence of the American people. In recent months they had been told that the NLF was close to defeat and now they were strong enough to take important buildings in the capital of South Vietnam. Another disturbing factor was that even with the large losses of 1967, the NLF could still send 70,000 men into battle.

The Tet Offensive proved to be a turning point in the war. In military terms it was a victory for the US forces. An estimated 37,000 NLF soldiers were killed compared to 2,500 Americans. However, it illustrated that the NLF appeared to have inexhaustible supplies of men and women willing to fight for the overthrow of the South Vietnamese government. In March, 1968, President Johnson was told by his Secretary of Defence that in his opinion the US could not win the Vietnam War and recommended a negotiated withdrawal. Later that month, President Johnson told the American people on national television that he was reducing the air-raids on North Vietnam and intended to seek a negotiated peace.

ambulence during the battle to recapture Hue during the Tet Offensive.

xx