On this day on 25th October

On this day in 1400 Geoffrey Chaucer, English poet, died. After working for Elizabeth de Burgh (Edward Ill's daughter-in-law), Chaucer served as a soldier in France. He was captured, but his friends, including the king, raised enough money to buy his freedom. Later he was employed by the king as a diplomat. In 1386 Chaucer was a Member of Parliament for Kent. At about this time he began to write his most important work, The Canterbury Tales. The book is a collection of stories told by a party of pilgrims on a journey from Southwark to Thomas Becket's shrine at Canterbury. As Chaucer chooses characters from a whole range of different backgrounds, the book provides an important insight into the social, religious and economic conditions of the 14th century.

On this day in 1415 Henry V of England, with his lightly armoured infantry and archers, defeats the heavily armoured French cavalry in the Battle of Agincourt.

On this day in 1760 King George III succeeds to the British throne on the death of his grandfather George II. In 1793 war broke out with France. Soon afterwards William Pitt brought in a bill suspending Habeas Corpus. Although denounced by Charles Fox and his supporters, the bill was passed by the House of Commons in twenty-four hours. Those advocating parliamentary reform were arrested and charged with sedition. Tom Paine managed to escape but others such as Thomas Hardy, John Thellwall and Thomas Muir were imprisoned.

To pay for the war Pitt was forced to increase taxation and had to raise a loan of £18 million. This problem was made worse by a series of bad harvests. When going to open parliament in October 1795, George III was greeted with cries of 'Bread', 'Peace' and 'no Pitt'. Missiles were also thrown and so Pitt immediately decided to pass a new Sedition Bill that redefined the law of treason.

On this day in 1806 Max Stirner, German philosopher was born. In 1844 Stirner published The Ego and Its Own. The book upset many on the left with its rejection of socialist ideology. Bruno Bauer, Ludwig Feuerbach, Moses Hess and Arnold Ruge, all wrote articles to defend their own views against Stirner's polemic. Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels also devoted a large section of their book, The German Ideology, to Stirner's work. The Ego and Its Own

The most revolutionary aspect of Stirner's book concerned his views on property: "There are some things that only belong to a few, and to which we others will from now on lay claim or siege. Let us take them, for one only comes into property by taking, and the property of which for the present we are still deprived came to the proprietors likewise only by taking. It can be utilized better if it is in the hands of us all than if the few control. Let us therefore associate ourselves for the purpose of this robbery... Liberty belongs to him who takes it... Take hold and take what you require! With this the war of all against all is declared. I alone decide what I will have!"

On this day in 1872 Mary Sheepshanks was born at Bilton vicarage, near Harrogate, North Yorkshire, the second of the thirteen surviving children of John Sheepshanks and his wife, Margaret Ryott. Her father, was later to become Bishop of Norwich.

Margaret Sheepshanks had seventeen children (four had died in infancy). Mary later recalled: "Hers had been a happy life; but in earlier years her nerves were overstrained beyond endurance and the real sweetness and generosity of her nature were sometimes over-clouded ... The entire lack of the element of pleasure in our home-life was no doubt largely due to the ceaseless worry and nervous strain of her incessant child bearing ... my Mother was swamped by babies."

In her book, Spinsters of this Parish (1984) Sybil Oldfield has argued: "It was hardly to be expected that Mrs Sheepshanks could give much individual attention or affectionate support to her eldest daughter during her fourteen subsequent pregnancies, nor did she. She was a woman who preferred all her sons to any of her daughters, and of her six daughters, Mary was the one for whom she cared least, being the plainest, the least feminine, and the most bookish as well as the most implacable of all her girls. But all Mrs Sheepshanks' children were very devoted to her - as children so often are to a mother of whose love they are deeply unsure."

Mary Sheepshanks had a difficult relationship with her father. Her biographer, Sybil Oldfield, has argued: "But the pity was that although her father was the most significant member of the family for Mary, Mary did not matter very much to him. She was neither a promising son nor a beautiful daughter. Time and again as a child and young girl she tried to impress him, but rarely, if ever, managed to do so. To counter her disappointment, Mary grew more critical of her father, weaning herself from her need of his praise and going her own way - even rejecting his religious faith. Yet she was the one among all his thirteen children who was most like him - sharing his mental and physical energy, his moral courage, his linguistic flair and his zest for travelling through dangerous and lonely parts of the globe. That part of her father to which she had whole-heartedly responded as a child - his sense of the justice due to others and the immovable courage of his convictions - Mary took into herself."

Mary was educated at Liverpool High School for Girls. In her unpublished autobiography she recalled: "At that time there was no bus or tram for the cross-country route... So at fourteen... I had to walk to the other side of the town, three miles each way through dingy streets and across brickfields with stagnant pools and dead cats." She added that it "was almost impossible to make friends, as all my school-fellows lived in the better-class neighbourhood near the school and were thus out of reach."

When she was seventeen, in 1889, she was sent to Germany to learn the language. Mary lived in Kassel and soon developed a strong interest in cultural events: "I had never before seen a play, nor heard a concert nor had I seen any good pictures... but theatre-going here was as much a matter of course as church-going was at home." She then moved onto Potsdam where she made several new friends: "How right the old Romans were to realise that what the people wanted was bread and games - or otherwise food and fun. We were young and enjoyed anything that meant meeting other young people."

In 1891 Mary went to Newnham College to study medieval and modern languages. She later recalled: "College life meant for me a new freedom and independence ... The mere living in Cambridge was a joy in itself; the beauty of it all, the noble architecture, the atmosphere of learning were balm to one's soul... To spend some of the most formative years in an atmosphere of things of the mind and in the acquisition of knowledge is happiness in itself and the results and memories are undying. Community life at its best, as in a college, brings contacts with people of varied interests and backgrounds and studying a wide range of subjects. Friendships are formed and new vistas opened. For a few years at least escape is possible from the worries and trivialities of domestic life."

Mary Sheepshanks developed a close relationship with Florence Melian Stawell: "Florence Melian Stawell... was the most striking personality at Newnham at that time. She was an Australian student of outstanding ability, striking physical beauty and grace. On one occasion when she entered a room full of people a man exclaimed, At last the gods have come down to earth in the likeness of a woman! ... She was in fact one of those rare individuals endowed with every gift... Melian Stawell was in her third year when I went up, and I saw a good deal of her and learnt much from her." Stawell introduced Sheepshanks to the work of Walt Whitman, George Meredith and Henrik Ibsen.

Another close friend at Cambridge University was Flora Mayor, who introduced her to her sister Alice: "Mary Sheepshanks is an awfully nice girl to talk to". Alice agreed: "We had lots of interesting talk. I think (Mary Sheepshanks) about the most interesting girl I know to talk to ... she talks a good deal about men and matrimony, religion, books, art (very intelligently which is more than most people do)... She is certainly very keen on men and would get on with them admirably I'm sure... it is inspiring to the intellect to have her to discuss things with, we differ exceedingly."

Mary Sheepshanks and Flora Mayor were both interested in history. Mary later wrote: "Fortunately I was able to stay up for a fourth year, and I enjoyed a course in moral Science, Psychology and History of Philosophy and Economics. How I wished I had entered for that course or for History from the beginning."

While at Newnham College Mary began to teach adult literacy classes in the poor working-class district of Barnwell. This experience turned her into a social reformer. She also became friends with Bertrand Russell, a strong advocate of free love and women's suffrage. He was also highly critical of organised religion. Her sister, Dorothy Sheepshanks, recalled that, "Mary came to hold very advanced views in many respects, views of which father disapproved." John Sheepshanks, who was Bishop of Norwich at the time, was so shocked by Mary's views on politics and religion that he insisted that Mary must not spend any of her future university vacations at home.

In October 1895, she joined the Women's University Settlement, later the Blackfriars Settlement, in Southwark. According to her biographer, Sybil Oldfield: "Mary Sheepshanks was a tall, upright woman with bespectacled, brilliantly blue eyes and a brusque manner. Incomparably articulate, her exceptional intellectual competence masked deep personal insecurity; she found it difficult to believe she was liked." Flora Mayor visited the settlement but admitted to her sister Alice that she could not do that kind of work: "I felt rather shy though I must say the Settlement people are very nice... I don't think I shall go again... The children are rather revolting I think on the whole." Mary Sheepshanks admitted that it was dispiriting that many of the people seemed "to be quite happy in poverty, hunger, and dirt, enlivened with drink".

Octavia Hill was one of those who visited the Women's University Settlement. At first she had been prejudiced against the whole scheme. E. Moberly Bell, the author of Octavia Hill (1942), has argued that "she believed so passionately in family life, that a collection of women, living together without family ties or domestic duties, seemed to her unnatural, if not positively undesirable." However, after spending time with the women she remarked: "They are all very refined, highly cultivated... and very young. They are so sweet and humble and keen to learn about things out of the ordinary line of experience."

In 1897 Mary Sheepshanks was appointed vice-principal of Morley College for Working Men and Women. She made a special effort to persuade under-privileged women to enroll at the college. Sheepshanks also recruited Virginia Woolf to teach history evening classes. Other lecturers at the college included Graham Wallas, Goldsworthy Lowes Dickinson and Ernest Shepherd. A member of the National Union of Women's Suffrage Societies she also invited Maud Pember Reeves and Christabel Pankhurst to lecture at the college.

In retrospect Mary felt that her responsibilities at Morley College had not been good for her in the long run: "It was a mistake to have taken an administrative post, and a light one at that, at such an early age. I ought to have been doing hard spade work and learning to be a good subordinate, a thing I never learned."

Mary Sheepshanks later recalled how much the college meant to the people in the area: "Very many of the students left home early in the morning by the workman's train, came straight from work to their classes and arrived home late, not having had any solid meal all day... It was distinctly a school for tired people."

Mary and Flora Mayor remained good friends. Sybil Oldfield, the author of Spinsters of this Parish (1984) pointed out: "Flora vvould call in for tea and sympathy with her friend Mary Sheepshanks in her lodgings in Stepney. Mary could always be relied upon for approval and encouragement in the matter of striking out independently and unconventionally, so Flora did not have to be at all defensive about the stage with her, but she did wish she could have reported a little more success. However, Mary did not depress Flora by claiming to be any more successful in life than she was. Flora could even feel that she was cheering Mary up by recounting her own inglorious struggle... One bond between the two of them, in addition to their wish to achieve something in the world, was their shared sense that they were not a success with men. Men might find both women stimulating to talk to, but they did not invite them out. Marriage was far from being their great aim in life; nonetheless it was a sore point that neither of them could, at the age of twenty-five, feel confident of any man's passionate affection."

On 23rd June, 1900, Mary, Flora Mayor, Ernest Shepherd and Frank Earp went to Queensgate House together. Flora wrote in her diary: "Mary Sheepshanks came to lunch looking very pretty. We met Ernest and Frank Earp and went on the river, most successful and most cheerful tea. Ernest was very lively, possibly owing to Mary. Mary talked a good deal about Mr. Fountain's engagement."

Flora believed that Shepherd was in love with Mary. However, in fact he really loved Flora. He was not earning enough money as an architect to marry her. In March 1903, Ernest took a well-paying post as part of the Architectural Survey of India. He then proposed to Flora. At first she hesitated because she did not want to be separated from her family. She wrote to her twin sister, Alice: "I don't like the thought of India... what am I to do without you?" Eventually she agreed to marry him.

Under instructions from Flora, Shepherd went to see Mary. That night he wrote to Flora: "I called on Mary Sheepshanks today and told her about ourselves; you know I said I should... Of course I did not expect her to care one way or the other and I don't think she did; but she spoke very nicely, and was pleased that I had come to tell her; so though it was very awkward, embarrassing and hateful I am very glad I did it."

In 1905 Mary Sheepshanks fell in love with Theodore Llewelyn Davies. However, he was in love with Meg Booth, the daughter of social investigator, Charles Booth. After she refused him, Davies committed suicide. Bertrand Russell wrote: "I never knew but one woman who would have been delighted to marry Theodore. She of course, was the only woman he wished to marry."

Mary was also attracted to Virginia Woolf, who she admitted exercised "an irresistible charm" over her. Sybil Oldfield has argued: "Mary found herself confiding in Virginia a great deal more than it retrospect she would have wished." Virginia did not share Mary's feelings. She wrote to Lytton Strachey: "Mary Sheepshanks deluged me till 1.30 in the morning with the most vapid and melancholy revelations - imagine 17 Sheepshanks in a Liverpool slum, and Mary (so she says) the brightest of the lot."

Mary wrote to Bertrand Russell about her failure to find someone who loved her: "It does seem to me as inevitable and as justifiable that one should want affection, as that one should want air and food, not as a reward, but because life is unbearable without. To the ordinary sort of woman like me with no particular talent or ambition, it is absolutely the only thing that matters. And this autumn I have felt so deserted. You are almost the only person who has been to see me or written to me.... The fact is I have a fair number of acquaintances, and hardly any friends. Everyone else seems to have their life full of people and interests, and I have failed to fill mine."

Initially, Mary Sheepshanks supported the Women Social & Political Union in their militant campaign to obtain women's suffrage. She was also a close friend of suffragettes such as Marion Wallace-Dunlop. According to Sybil Oldfield: "Mary Sheepshanks's feminism was inspired both by outrage at the brutal injustice suffered by women and by faith that emancipated, enfranchised women could help to humanize the world."

In April 1907 she invited Christabel Pankhurst to speak in a debate on women's suffrage at the Morley College for Working Men and Women. During the debate she argued: "We are absolutely determined to have our way, and to have our say in the government of affairs. We are going to develop on our own lines and listen to the pleadings of our inner nature. We shall think our own thoughts and strengthen our own intelligence. We want the abolition of sex in the choice of legislative power as well as privilege. For the present we want the woman to have what the men have." Mary Sheepshanks wound up the debate, supporting the motion for women's enfranchisement on two grounds: (1) that the vote would benefit women, (2) that it would benefit the state.

In April 1909, Mary arranged for Maud Pember Reeves to talk about the positive social consequences of women's enfranchisement in her native New Zealand. She also organized debates on the efforts of the Fabian Society to raise the wages of low-paid women workers.

As Sybil Oldfield has pointed out: "Her attitude to the Suffragettes, like that of many of her fellow Suffragists, was ambivalent. She disliked their methods, having an aversion to violence, but she greatly admired their individual acts of bravery and doubted whether she could have shown similar courage herself."

Mary Sheepshanks continued to campaign for the National Union of Suffrage Societies and in her biography, she writes about how she went with Philippa Fawcett, the daughter of Millicent Fawcett, to speak in Bicester: "While we were out at a meeting some young men, sons of neighbouring squires, broke into our bed-rooms and made hay of them. A few days later I had friends to dinner in London, including Jos. Wedgewood, who had previously rescued me and a friend from an angry election crowd in the Potteries. He took up the matter in the House of Commons, and the Home Secretary undertook to look into it... The father of one of the young men offered an apology - provided I would not say I had received one."

In 1913 she went on a suffrage lecture tour of Europe, speaking in French or German on women and local government, industry, temperance, and education. Later that year Jane Addams persuaded her to become secretary of the International Women's Suffrage Alliance and the editor of its journal, Ius Suffragii (The Law of Suffrage). Members of the organisation included Millicent Fawcett, Margery Corbett-Ashby, Vida Goldstein, Isabella Ford, Aletta Jacobs, Rosika Schwimmer, Ethel Snowden, Chrystal Macmillan, Crystal Eastman, Dora Montefiore, Helena Swanwick, Maude Royden and Kathleen Courtney.

Sheepshanks was a strong opponent of Britain's involvement in the First World War. She later wrote: "The war brought me as near despair as I have ever been... That many of the best men in every country should forswear their culture, their humanity, their intellectual efforts... to wallow in the joys of regimentation, brainlessness, and... the primitive delights of destruction! For they did... everywhere, in every belligerent country, men were doing the same things; patriotically rushing to the defence of their homes and loved ones, taunting and imprisoning, (if they did not shoot) the small number of young men who refused to join them; and disseminating and believing the same atrocity stories against each other. It was lonely in those days. I felt that men had dropped their end of the burden of living, and left women to carry on."

The day after war was declared, Charles Trevelyan began contacting friends about a new political organisation he intended to form to oppose the war. This included two pacifist members of the Liberal Party, Norman Angell and E. D. Morel, and Ramsay MacDonald, the leader of the Labour Party. A meeting was held and after considering names such as the Peoples' Emancipation Committee and the Peoples' Freedom League, they selected the Union of Democratic Control (UDC).

The founders of the UDC produced a manifesto and invited people to support it. Over the next few weeks several leading figures joined the organisation. This included Mary Sheepshanks, J. A. Hobson, Charles Buxton, Frederick Pethick-Lawrence, Arnold Rowntree, Morgan Philips Price, George Cadbury, Helena Swanwick, Fred Jowett, Tom Johnston, Philip Snowden, Ethel Snowden, David Kirkwood, William Anderson, Isabella Ford, H. H. Brailsford, Israel Zangwill, Bertrand Russell, Margaret Llewelyn Davies, Konni Zilliacus, Margaret Sackville and Olive Schreiner.

On 14th October, 1914, Mary Sheepshanks wrote in Ius Suffragii: "Each nation is convinced that it is fighting in self-defence, and each in self-defence hastens to self-destruction. The military authorities declare that the defender must be the aggressor, so armies rush to invade neighbouring countries in pure defence of their own hearth and home, and, as each Government assures the world, with no ambition to aggrandise itself. Thousands of men are slaughtered or crippled... art, industry, social reform, are thrown back and destroyed; and what gain will anyone have in the end? In all this orgy of blood, what is left of the internationalism which met in congresses, socialist, feminist, pacifist, and boasted of the coming era of peace and amity. The men are fighting; what are the women doing? They are, as is the lot of women, binding up the wounds that men have made."

Sheepshanks also called for a negotiated peace and called for an end to the arms race: "Armaments must be drastically reduced and abolished, and their place taken by an international police force. Instead of two great Alliances pitted against each other, we must have a true Concert of Europe. Peace must be on generous, unvindictive lines, satisfying legitimate national needs, leaving no cause for resentment such as to lead to another war."

Mary Sheepshanks joined forces with Isabella Ford and Elsie Inglis to agitate for the admission of vast numbers of Belgian refugees into Britain who had been made homeless because of the fighting on the Western Front. The women's suffrage newspaper, The Common Cause, reported: "Miss Sheepshanks, in an admirable speech, gave an appalling account of the burden which Holland is shouldering. In one province, with 300,000 inhabitants, there are 400,000 refugees. In a village with 800 inhabitants, 2,000 refugees. The situation is impossible, and it is clear that the Belgians must either come here or return to Belgium where their sons would be liable to German military service, and their daughters be unsafe. Public opinion in Great Britain should demand their coming here, and should back the demand by large offers of hospitality from municipal authority."

In January 1915 Mary Sheepshanks published an open Christmas letter to the women of Germany and Austria, signed by 100 British women pacifists. The signatories included Helena Swanwick, Emily Hobhouse, Margaret Bondfield, Maude Royden, Sylvia Pankhurst, Anne Cobden Sanderson, Eva Gore-Booth, Margaret Llewelyn Davies and Marion Phillips. It included the following: "Do not let us forget our very anguish unites us, that we are passing together through the same experiences of pain and grief. We pray you to believe that come what may we hold to our faith in peace and goodwill between nations."

At a Council meeting of the National Union of Women's Suffrage Societies held in February 1915, Millicent Fawcett attacked the peace efforts of people like Mary Sheepshanks. Fawcett argued that until the German armies had been driven out of France and Belgium: "I believe it is akin to treason to talk of peace." After a stormy executive meeting in Buxton all the officers of the NUWSS (except the Treasurer) and ten members of the National Executive resigned. This included Chrystal Macmillan, Kathleen Courtney, Catherine Marshall, Eleanor Rathbone and Maude Royden, the editor of the The Common Cause.

In April 1915, Aletta Jacobs, a suffragist in Holland, invited suffrage members all over the world to an International Congress of Women in the Hague. Some of the women who attended included Mary Sheepshanks, Jane Addams, Alice Hamilton, Grace Abbott, Emily Bach, Lida Gustava Heymann, Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence, Emily Hobhouse, Chrystal Macmillan, Rosika Schwimmer. At the conference the women formed the Women's International League for Peace and Freedom. Afterwards, Jacobs, Addams, Macmillan, Schwimmer and Balch went to London, Berlin, Vienna, Budapest, Rome, Berne and Paris to speak with members of the various governments in Europe.

Mary Sheepshanks, like many people on the left, welcomed the Russian Revolution and the overthrow of Tsar Nicholas II. She wrote in the Ius Suffragii : "Women Suffragists all over the world will welcome the liberation of the hundreds of millions of inhabitants of that vast empire... Freedom of speech, of religion, of the press, of public meetings; freedom to work or abstain from working: freedom for nationality."

In 1918 Mary Sheepshanks was appointed secretary of the Fight the Famine Council, an organisation that had been founded by Gilbert Murray, Richard H. Tawney, Leonard Woolf, John Maynard Keynes, Olive Schreiner, and others to educate public opinion concerning the need for a new, just economic order in Europe. In 1920, Sheepshanks lobbied the League of Nations unsuccessfully for the immediate admission of Germany and the revision of the reparations clauses of the Treaty of Versailles.

During this period she became friends with Paulina Luisi. Sheepshanks later recalled "a woman of outstanding ability and genius... whose vitality and dominating personality would make her a leader in the country in the world." Flora Mayor noted in her diary that Mary was "suffering a good deal from arthritis" and that "she likes the pacifist set she has round her but she is very lonely".

Mary Sheepshanks replaced Emily Bach as international secretary of the Women's International League for Peace and Freedom in 1927. In September 1928 she headed another deputation to the League of Nations to present an urgent memorandum calling for a world disarmament conference. According to her biographer, Sybil Oldfield: "In 1929 she organized the first scientific conference on modern methods of warfare and the civilian population in Frankfurt, and in 1930 the first Conference on Statelessness in Europe (held in Geneva). Feeling increasingly isolated on the Women's International League executive among its French or German left-extremists, however, she resigned in 1931. She then went on an undercover fact-finding mission to the Ukrainians of Galicia, whose brutal oppression by the Polish regime of Marshal Pilsudski she proceeded to publicize."

In 1936 she was involved in sending medical help to Republicans fighting in the Spanish Civil War. Other members of the group included Leah Manning, George Jeger, Lord Faringdon, Arthur Greenwood, Tom Mann, Ben Tillett, Harry Pollitt and Mary Redfern Davies. In 1938 she was busy finding homes for Basque child refugees. Her house in Highgate became a place of refuge for political dissidents fleeing from Adolf Hitler and Joseph Stalin.

Sheepshanks became increasingly concerned by the increasing power of Adolf Hitler in Nazi Germany and on the outbreak of the Second World War in 1939 she renounced her pacifism. However, she remained opposed to blanket bombing and complained bitterly about the dropping of the atom bomb on Hiroshima and Nagasaki in 1945.

In November 1945 she wrote to her niece, Pita Sheepshanks, about how she was a socialist: "In my youth I was a liberal, in fact a Radical, and I have long been a Socialist. I admit that this war has made me deeply pessimistic, the incredible savagery and beastliness of the Germans and the immeasurable suffering they caused make me despair of human nature, and now I expect this ghastly atomic bomb will be used to destroy the world. There are decent and wise people but they are bested by the evil ones."

Mary Sheepshanks did not enjoy good health in her final years, suffering from crippling arthritis. At the age of 79 she underwent an operation for cancer. An old friend, Margery Corbett Ashby, was one of her regular visitors: "She had so many general interests - music, books and art as well as politics. She looked on mankind as a family.

Another visitor was Denis Richards, a former principal of Morley College. "Her (Mary Sheepshanks) best feature was undoubtedly her eyes, which even at her late age were brilliantly blue and alive with intelligence and humour. Apart from that, and the general alertness of her face, she looked very much like a German caricature of an English spinster in the early years of this century."

In 1955 Sheepshanks began work on her memoirs. Her publisher wanted her to add many more "gossipy" comments on the famous people she had met in her lifetime. According to a friend she "absolutely refused to alter it or touch it again."

Mary Sheepshanks, nearly blind and paralysed, and faced with the prospect of being placed in a care-home, after her daily help resigned after a quarrel with a neighbour, committed suicide at her home in Hampstead on 21st January 1960.

On this day in 1873 Patricia Woodlock, the first of four children of Marion Teresa Martin Woodlock (1847-1913) and David Woodlock (1842-1929) was born in Liverpool. At the time her father was an assistant in a drapery shop. In his spare time, he studied at St George's Museum, Walkley, which had been founded by John Ruskin for the education of local workers.

After leaving school Patricia Woodlock worked as an apprentice to a female confectioner and was living at 92 Division Street, Sheffield. (2) She later returned home and lived with her parents at 46 Nicander Road, Sefton Park, Liverpool. David Woodlock now described himself as an "Artist" He was also a socialist and a member of the Independent Labour Party and encouraged his daughter to be involved in politics.

In 1903 Woodlock joined the Liverpool branch of the Women Social & Political Union. In an article in Votes for Women she explained why she felt so strongly about the subject: "A member of Parliament recently spoke of members of the WSPU as being possessed by fanaticism, and it occurred to her that politicians stood in need of a new dictionary – so many words having a different meaning as applied to women or to men – this word fanaticism simply meant enthusiasm."

In March 1907 Woodlock came to London to take part in the Woman's Parliament at Caxton Hall. She was arrested in Parliament Square and as this was her third offence she was sent to prison for a month. When she left prison she was described along with Emma Sproson as being "the most unruly and turbulent of spirits". Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence argued that Woodlock was "'the heart of our Movement... the centre, the pivot upon which every part of it turns."

Patricia Woodlock and Mabel Capper organized a series of public demonstrations at Manchester parks in favour of women's suffrage. The demonstration held at Heaton Park on 19th July 1908, was attended by an estimated 50,000 people. The Manchester Evening News described the demonstration as "decorous", "informative" and "logical".

Members of the WSPU had given out leaflets promoting the meeting in Manchester city centre the previous day. Speakers included Emmeline Pankhurst, Christabel Pankhurst and Adela Pankhurst. Patricia Woodlock and Mabel Capper decided to try making a speech on women's suffrage in the Manchester Royal Exchange. According to Carole O'Reilly: "The Royal Exchange, this bastion of male enterprise was entered by Capper and Woodcock where they attempted to make a speech about women's suffrage but were asked to leave the Exchange or be arrested."

In 1909 Patricia Woodlock was appointed as organiser of Liverpool WSPU. In March Woodlock was one of the Liverpool delegates to the Second Women's Parliament in Caxton Hall, London. Woodlock was arrested along with Dora Marsden, and was sentenced to three months in prison because she was as a persistent offender. (11) At the time it was the longest sentence given to a member of the WSPU. Christabel Pankhurst described Woodlock as "one of those who are the great strength of the women's movement, for she is fearless, loyal and unselfish, ready to do the smallest or greatest service, as a speaker and above all as a fighter."

In the House of Commons MPs complained about the length of the sentence. Herbert Gladstone, the Home Secretary stated that considering her previous behaviour the sentence was justified: "This lady, who had three times previously been committed for the same class of offence, and who intimated that if released she would straightway do the same thing, was only required to give securities for good behaviour, and can therefore come out of prison at any time on complying with the order of the Court. I see no reason for interference on my part."

Votes for Women published a profile of Woodlock while she was in prison: "But we who know her know that Patricia Woodlock will never be broken. She has not once faltered or looked back since she heard the call for womanhood of the world more than three years ago. It was in December 1905, that she tried with other Lancashire women to enter the House that is supposed to represent the people of Great Britain. She was sent to Holloway for two weeks, which entailed spending her Christmas in prison. A few weeks later, in February 1907, she again formed one of the deputations of fifty-nine women, and rather than give a pledge that was against her conscience, she suffered a month in Holloway. If the authorities thought this would quell her spirit they were entirely wrong, for in March of the same year, after only a few days of the freedom that those who have been in prison can alone appreciate at its full value, she tried again to put the woman's demand for enfranchisement before the Prime Minister and was sent to prison for one month without the option of a fine. Miss Woodlock has done unceasing and enthusiastic work for the movement in Liverpool and elsewhere, her devotion winning her the love and respect of all with whom she came into contact, and bringing to her own heart the happiness that results from a complete abnegation of self for the sake of humanity."

While she was in prison she was visited by Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence. Patricia's father, David Woodlock, sent her a letter of thanks and pointed out that he fully supported his daughter's actions: "I am very sure that anything that I can put on paper will but inadequately express my feeling towards you and your thoughtfulness on this occasion and throughout the whole time of my daughter's connection with the movement. I was especially touched (who would not be?) at the fine demonstration of comradeship and greatness of heart displayed by you when, on the morning of your own release from prison, your first public utterance – bold, courageous, and in every way worthy of you – was of sympathy and comfort for the one who still remained behind. Rest assured you will not be disappointed in her. I know my daughter well, and her feeling towards the cause she has at heart, especially the two fine souls she has always looked up to as the ensign and embodiment of that cause, Mrs Pankhurst and yourself; and I think I can safely say that you will always find her ready, loyal, and courageous. 'Britons never shall be slaves'. Indeed! Not much likelihood while we have these young heroines as examples of the prospective mothers of the race!"

On her release on 16th June, Woodlock was greeted by Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence and several hundred supporters: "As early as half-past seven a large crowd assembled opposite the prison gates, augmented from time to time by the curious or sympathetic among the passers-by, and time went on the numbers swelled, until several hundreds were waiting, the enlivening strains of Bryer's band and the vigorous efforts of bill-distributors making the time pass quickly. As the hour of release drew near a hush fell on the assembled crowd, and when the gate opened and a solitary figure emerged, a mighty cheer went up. Miss Woodlock, who looked pale and thin, but had the light of indomitable courage burning in her eyes, at once entered Mrs Pethick Lawrence's motor-car, which was in waiting, and was driven away, the crowd following, cheering and singing the Marseillaise. It was inspiriting to see the numbers of strangers – principally girls and working men – joining in the song and waving aloft their tool-bags and dinner-bundles."

Patricia Woodlock was taken to the Inns of Court where Emmeline Pankhurst gave a speech acknowledging her commitment to the cause: "Mrs Pankhurst... said, no woman had deserved more highly than this brave pioneer in the cause of woman's freedom… During the time she had been a member of the Union, Patricia Woodlock had over and over again taken a front place in the fighting line, and had proved her devotion to the cause by being five times arrested and four times imprisoned… Patricia Woodlock, whose courage in sustaining prison treatment had fired then with enthusiasm."

Mary Gawthorpe also addressed the meeting: "The women of the country honoured Patricia Woodlock because they loved and honoured the case so much, and because to every woman there always came a day when she realised how infinitely more great the cause itself was than any personal sacrifice that might be made for it." Woodlock replied that it "was the object of the Government in sending women to prison in this so-called century of progress. She supposed that the object of men in political power was to stop women for agitating, but they did not know women, and the more they sent them to prison the more determined the women were when they came out.... When women were determination to have their rights, they would get them. They were not asking for favours because they were women; all they wanted was equality as subject."

On 22nd September 1909 Patricia Woodlock, Mary Leigh, Charlotte Marsh, Laura Ainsworth, Mabel Capper and Rona Robinson conducted a rooftop protest at Bingley Hall, Birmingham, where Herbert Asquith was addressing a meeting from which all women had been excluded. Using an axe, Leigh removed slates from the roof and threw them at the police below. Sylvia Pankhurst later recalled: "No sooner was this effected, however, than the rattling of missiles was heard on the other side of the hall, and on the roof of the house, thirty feet above the street, lit up by a tall electric standard was seen the little agile figure of Mary Leigh, with a tall fair girl (Charlotte Marsh) beside her. Both of them were tearing up the slates with axes, and flinging them onto the roof of the Bingley Hall and down into the road below-always, however, taking care to hit no one and sounding a warning before throwing. The police cried to them to stop and angry stewards came rushing out of the hall to second this demand, but the women calmly went on with their work."

The Freeman's Journal reported: "Mary Leigh and Mabel Capper have long been among the most reckless members of the suffragist movement. They were two of a large band who visited Birmingham in September, 1909, and were arrested with others on charge arising out of a desperate and well-organised attempt to storm Bingley Hall where Mr Asquith was speaking to an audience of ten thousand. Leigh and another, eluding the vigilance of the police, climbed on to the roof of an adjoining factory, from which she threw ginger beer bottles, slates, and other missiles on the glass roof of Bingley Hall, and into the street when the Premier was passing in a motor car. While awaiting his appearance the women amused themselves by throwing projectiles at the crowd in the street and the police, several officers being struck. A policeman who climbed on the roof – a hazardous undertaking – found Leigh with her boots off, jumping about like a cat, as he described it, and armed with an axe used for the purpose of ripping slates from the roof: 'Come on up at your peril,' the women shouted to the officers, who were struck several times before effecting an arrest."

Leigh got four months's imprisonment, Marsh three months, Woodlock a month and others got fourteen days. They immediately decided to go on hunger-strike, a strategy developed by Marion Wallace-Dunlop a few weeks earlier. Wallace-Dunlop had been immediately released when she had tried this in Holloway Prison, but the governor of Winson Green Prison, was willing to feed the three women by force.

In November 1909, after release, Patricia Woodlock and Laura Ainsworth approached the prison doctor, Dr. Ernest Helby, in the street. He had force-fed Woodlock and others and the two women demanded the immediate release of fellow suffragette Charlotte Marsh. Later that day Dr. Helby's windows were found to be smashed, but no legal action was taken. Marsh was eventually released on 9th december. she had been fed by stomach tube a total of 139 times.

The Conciliation Bill was designed to conciliate the suffragist movement by giving a limited number of women the vote, according to their property holdings and marital status. After a two-day debate in July 1910, the Conciliation Bill was carried by 109 votes and it was agreed to send it away to be amended by a House of Commons committee. However, when Keir Hardie, the leader of the Labour Party, requested two hours to discuss the Conciliation Bill, H. H. Asquith made it clear that he intended to shelve it.

Emmeline Pankhurst was furious at what she saw as Asquith's betrayal and on 18th November, 1910, arranged to lead 300 women from a pre-arranged meeting at the Caxton Hall to the House of Commons. Pankhurst and a small group of WSPU members, were allowed into the building but Asquith refused to see them. Women, in "detachments of twelve" marched forward but were attacked by the police.

Votes for Women reported that 159 women and three men were arrested during this demonstration that became known as "Black Friday". This included Patricia Woodlock, Ada Wright , Catherine Marshall, Eveline Haverfield, Anne Cobden Sanderson, Mary Leigh, Vera Holme, Louisa Garrett Anderson, Kitty Marion, Clara Giveen, Eileen Casey, Lilian Dove-Wilcox and Grace Roe.

Sylvia Pankhurst later described what happened: "As, one after the other, small deputations of twelve women appeared in sight they were set upon by the police and hurled aside. Mrs Cobden Sanderson, who had been in the first deputation, was rudely seized and pressed against the wall by the police, who held her there by both arms for a considerable time, sneering and jeering at her meanwhile.... Just as this had been done, I saw Miss Ada Wright close to the entrance. Several police seized her, lifted her from the ground and flung her back into the crowd. A moment afterwards she appeared again, and I saw her running as fast as she could towards the House of Commons. A policeman struck her with all his force and she fell to the ground. For a moment there was a group of struggling men round the place where she lay, then she rose up, only to be flung down again immediately. Then a tall, grey-headed man with a silk hat was seen fighting to protect her; but three or four police seized hold of him and bundled him away. Then again, I saw Miss Ada Wright's tall, grey-clad figure, but over and over again she was flung to the ground, how often I cannot say. It was a painful and degrading sight. At last, she was lying against the wall of the House of Lords, close to the Strangers' Entrance, and a number of women, with pale and distressed faces were kneeling down round her. She was in a state of collapse."

Several women reported that the police dragged women down the side streets. "We knew this always meant greater ill-usage.... The police snatched the flags, tore them to shreds, and smashed the sticks, struck the women with fists and knees, knocked them down, some even kicked them, then dragged them up, carried them a few paces and flung them into the crowd of sightseers." It was claimed that two women, Cecilia Haig and Henria Williams, died because of the beatings they endured that day. "I saw Celilia Haig go out with the rest; a tall, strongly built, reserved woman, comfortably situated, who in ordinary circumstances might have gone through life without receiving an insult, much less a blow. She was assaulted with violence and indecency, and died in December 1911, after a painful illness, arising from her injuries. Henria Williams, already suffering from a weak heart, did not recover from the treatment she received that night in the Square, and died on January 1st."

The photograph of Ada Wright on the front page of The Daily Mirror the next day caused a great deal of embarrassment to the Home Office and the government demanded that the negative be destroyed. (28) Wright told a reporter that she had been at seven suffragette demonstrations, but had "never known the police so violent." (29) Charles Mansell-Moullin, who had helped treat the wounded claimed that the police had used "organised bands of well-dressed roughs who charged backwards and forwards through the deputations like a football team without any attempt being made to stop them by the police."

Sylvia Pankhurst believed that Winston Churchill, the Home Secretary, had encouraged this show of force. "Never, in all the attempts which we have made to carry our deputations to the Prime Minister, have I seen so much bravery on the part of the women and so much violent brutality on the part of the policeman in uniform and some men in plain clothes. It was at the same time a gallant and a heart-breaking sight to see those little deputations battling against overwhelming odds, and then to see them torn asunder and scattered, bruised and battered, against the organized gangs of rowdies. Happily, there were many true-hearted men in the crowd who tried to help the women, and who raised their hats and cheered them as they fought. I found out during the evening that the picked men of the A Division, who had always hitherto been called out on such occasions, were this time only on duty close to the House of Commons and at the police station, and that those with whom the women chiefly came into contact had been especially brought in from the outlying districts. During our conflicts with the A Division they had gradually come to know us, and to understand our aims and objects, and for that reason, whilst obeying their orders, they came to treat the women, as far as possible, with courtesy and consideration. But these men with whom we had to deal on Friday were ignorant and ill-mannered, and of an entirely different type. They had nothing of the correct official manner, and were to be seen laughing and jeering at the women whom they maltreated."

Churchill had been a long-term opponent of votes for women. As a young man he argued: "I shall unswervingly oppose this ridiculous movement (to give women the vote)... Once you give votes to the vast numbers of women who form the majority of the community, all power passes to their hands." His wife, Clementine Churchill, was a supporter of votes for women and after marriage he did become more sympathetic but was not convinced that women needed the vote. When a reference was made at a dinner party to the action of certain suffragettes in chaining themselves to railings and swearing to stay there until they got the vote, Churchill's reply was: "I might as well chain myself to St Thomas's Hospital and say I would not move till I had had a baby." However, it was the policy of the Liberal Party to give women the vote and so he could not express these opinions in public.

Henry Brailsford was commissioned to write a report on the way that the police dealt with the demonstration. He took testimony from a large number of women, including Mary Frances Earl: "In the struggle the police were most brutal and indecent. They deliberately tore my undergarments, using the most foul language - such language as I could not repeat. They seized me by the hair and forced me up the steps on my knees, refusing to allow me to regain my footing... The police, I understand, were brought specially from Whitechapel."

Paul Foot, the author of The Vote (2005) has pointed out, Brailsford and his committee obtained "enough irrefutable testimony not just of brutality by the police but also of indecent assault - now becoming a common practice among police officers - to shock many newspaper editors, and the report was published widely". However, Edward Henry, the Commissioner of the Metropolitan Police, claimed that the sexual assaults were committed by members of the public: "Amongst this crowd were many undesirable and reckless persons quite capable of indulging in gross conduct."

Black Friday was the last militant action took for the WSPU. She had been imprisoned seven times over a three year period. At the time of the 1911 Census, Patricia Woodlock (36) was living with her parents, David (67), Marion (63) and her sister and brother: Evangeline (26) and Charles (24) at 46 Nicander Road, Sefton Park, Liverpool.

In 1919 and 1920, Patricia Woodlock was living with her father, David Woodlock, her married sister and brother-in-law (Mrs Evangeline Smith and Edward Smith) in Greenbank Road, West Toxteth, Liverpool. In 1938 - 1939 Patricia Woodlock was living with her married sister Mrs Evangeline Smith at 6 Victoria Park, Wavertree, Liverpool.

Patricia Woodlock, aged 87, died in Wandsworth in 1961.

On this day in 1881 Pablo Picasso, Spanish artist was born The town of Guernica is situated 30 kilometers east of Bilbao, in the Basque province of Vizcaya. Guernica was considered to be the spiritual capital of the Basque people.

On the outbreak of the Spanish Civil War Guernica had a population of about 7,000 people. On 26th April 1937, Guernica was bombed by the German Condor Legion. As it was a market day the town was crowded. The town was first struck by explosive bombs and then by incendiaries. As people fled from their homes they were machine-gunned by fighter planes. The three hour raid completely destroyed the town. It is estimated that 1,685 people were killed and 900 injured in the attack.

On this day in 1882 John T. Flynn, American journalist was born. Flynn became concerned about President Franklin D. Roosevelt's foreign policy. In 1936 he described Roosevelt as "a born militarist" and argued that he would "do his best to entangle us" in an European war. Flynn also compared Roosevelt with Benito Mussolini and wrote: "We seem to be a long way off from the kind of Fascism which we behold in Italy today, but we are not so far from the kind of Fascism which Mussolini preached in Italy before he assumed power, and we are slowly approaching the conditions which made Fascism there possible."

In September 1940, Flynn helped establish the America First Committee (AFC). The America First National Committee included Flynn, Robert E. Wood and Charles A. Lindbergh. Supporters of the organization included Burton K. Wheeler, Hugh Johnson, Robert LaFollette Jr., Hamilton Fish and Gerald Nye.

The AFC soon became the most powerful isolationist group in the United States. The AFC had four main principles: (1) The United States must build an impregnable defense for America; (2) No foreign power, nor group of powers, can successfully attack a prepared America; (3) American democracy can be preserved only by keeping out of the European War; (4) "Aid short of war" weakens national defense at home and threatens to involve America in war abroad.

On this day in 1891 Charles Coughlin was born. After graduating from St. Michael's College in Toronto, he studied for the priesthood at St. Basil's Seminary and was ordained in 1916. During his training Coughlin was deeply influenced by the encyclical On the Condition of the Working Class, published by Pope Leo XIII in 1891. In this document the Pope called for far-reaching reforms to create a more just society in order to counter the growing support for Socialism in the world.

After assisting in several parishes in the Detroit area, Coughlin was assigned to the new Shrine of the Little Flower Church in Royal Oak, Michigan in 1926. At the time the parish only had 25 families, but Coughlin was such a popular preacher he was later able to build a church to hold 600 people.

On 3rd October 1926 he started a weekly broadcast over the local radio station. Initially, the broadcast was intended for children but it gradually changed to adult topics and Coughlin began expressing his views on the need for social reform. The Ku Klux Klan, upset by his views, arranged for a blazing cross planted on the lawn. However, he was very popular with most people and within four years CBS was broadcasting Coughlin's radio programme throughout the nation.

Coughlin warned of the dangers of "socialism, communism, and kindred fallacious social and economic theories". Like Pope Leo XIII, Coughlin believed the best way of combating the appeal of these ideologies was the introduction of reforms that would make America a more equal society. This included industrialists paying their workers a "just and living wage" and "providing old age compensation insurance." He also denounced the greed and corruption of America's industrialists and warned about the dangers of the "concentration of wealth in the hands of the few."

Coughlin developed a reputation for being an expert on the growth of the Communist Party in the United States and in July 1930, Hamilton Fish invited him to appear before the House of Representatives Committee to Investigate Communist Activities. Coughlin took the opportunity to criticize left-wing groups in America but he shocked the Committee by also attacking leading industrialists such as Henry Ford.

At this time Coughlin began to criticize the government of President Herbert Hoover. CBS, concerned by this development, warned him to "tone down" his broadcasts. When Coughlin refused, CBS decided not to renew his contract when it expired in April 1931. Coughlin responded by organizing his own radio network which eventually grew to over 30 stations.

During the 1932 presidential election, Coughlin advocated that his listeners should vote for Franklin D. Roosevelt. After the election Coughlin gave his support to Roosevelt's New Deal. He continued with his radio broadcasts where he advocated the nationalization of gold and the revaluation of the dollar. Coughlin continued to be extremely popular and the first edition of his complete radio discourses, published in 1933, quickly sold over a million copies.

In 1935 Coughlin started a campaign to restructure the Federal Reserve System and urged Roosevelt to take full government control over the nation's banking system and to establish a Central Bank. Coughlin also became involved in trade unions. He established the Automotive Industrial Workers Association (AIWA) in Detroit in direct competition with the more radical United Auto Workers. Coughlin also joined Huey Long in the campaign to persuade President Franklin D. Roosevelt to support the paying of the Bonus Bill, a large sum of money owed to the American veterans of the First World War.

Coughlin gradually grew disillusioned with Roosevelt and on 11th November, 1934, he announced the formation of the National Union of Social Justice. At this time some observers claimed that Father Coughlin was the second most important political figure in the United States. It was estimated that Coughlin's radio broadcasts were getting an audience of 30 million people. He was also having to employ twenty-six secretaries to deal with the 400,000 letters a week he was receiving from his listeners.

According to Wallace Stegner "Father Coughlin had a voice of such mellow richness, such manly, heart-warming, confidential intimacy, such emotional and ingratiating charm, that anyone tuning past it on the radio dial almost automatically returned to hear it again." As well as his radio broadcasts, Coughlin also began publishing Social Justice Weekly, a journal which soon achieved a circulation of over one million copies.

In May 1935 Coughlin began having talks with Huey Long, Francis Townsend, Gerald L. K. Smith, Milo Reno and Floyd B. Olson about a joint campaign to take on President Franklin D. Roosevelt in the 1936 presidential elections. Long was expected to the candidate but he was assassinated on 8th September, 1935.

After the death of Long, Joseph Kennedy attempted to reconcile Father Coughlin and Roosevelt. The conference in September 1935 was a failure and the following year Coughlin joined with Francis Townsend, Gerald L. K. Smith and followers of the late Huey Long to take on Roosevelt in the 1936 presidential election. The National Union of Social Justice selected William Lepke from North Dakota, as the party's candidate, but he won only 882,479 votes compared to Franklin D. Roosevelt (27,751,597) and Alfred Landon (16,679,583).

After this defeat Coughlin's replaced the National Union of Social Justice with the Christian Front and concentrated on the dangers of communism. Coughlin also became an isolationist and one of his campaign slogans was: "Less care for internationalism and more concern for national prosperity."

In the late 1930s Coughlin moved sharply to the right and accused Franklin D. Roosevelt of "leaning toward international socialism or sovietism". He also praised the actions of Adolf Hitler and Benito Mussolini in the fight against communism in Europe. On 20th November 1938, Coughlin defended the activities of the Nazi Government as a necessary defence against the Soviet Union.

Arthur Miller wrote: "Father Charles E. Coughlin, who by 1940 was confiding to his ten million Depression-battered listeners that the president was a liar controlled by both the Jewish bankers and, astonishingly enough, the Jewish Communists, the same tribe that twenty years earlier had engineered the Russian Revolution... He was arguing... that Hitlerism was the German nation's innocently defensive response to the threat of Communism, that Hitler was only against 'bad Jews', especially those born outside Germany."

Like Joseph Goebbels, Coughlin claimed that Marxist atheism in Europe was a Jewish plot. Coughlin also attacked the influence of Jews in America and this resulted in him being described as a fascist. In April 1941, Coughlin endorsed the America First Committee. However, his now open Anti-Semitism made this endorsement a mixed blessing for the organization.

In January 1940 the FBI raided the New York branch of the Christian Front and uncovered a cache of weapons. J. Edgar Hoover claimed that his officers had discovered that members of the organization planned to murder Jews, Communists and "a dozen Congressmen." Although Coughlin was not directly involved in this plot, the publicity it generated severely damaged his reputation.

Coughlin's opinions became more extreme. In September 1940 he described President Franklin D. Roosevelt as "the world's chief war-monger". The following year he wrote in Social Justice: "Stalin's idea to create world revolution and Hitler's so- called threat to seek world domination are not half as dangerous combined as is the proposal of the current British and American administrations to seize all raw materials in the world. Many people are beginning to wonder who they should fear most - the Roosevelt-Churchill combination or the Hitler-Mussolini combination."

When the United States entered the Second World War the National Association of Broadcasters arranged for Coughlin radio broadcasts to be brought to an end. The Post Office also banned his weekly newspaper, Social Justice, from the mail. On 1st May 1942, Archbishop Francis Mooney ordered Coughlin to bring an end to his political activities. He was warned that if he refused he would be defrocked.

Charles Edward Coughlin retired from the Shrine of the Little Flower Church in 1966. He continued to write pamphlets denouncing Communism until his death on 27th October, 1979.

On this day in 1917 it was the Old Style date of the October Revolution in Russia. The Red Guards surrounded the Winter Palace. Inside was most of the country's Cabinet, although Alexander Kerensky had managed to escape from the city. The palace was defended by Cossacks, some junior army officers and the Woman's Battalion. At 9 p.m. The Aurora and the Peter and Paul Fortress began to open fire on the palace. Little damage was done but the action persuaded most of those defending the building to surrender. The Red Guards, led by Vladimir Antonov-Ovseenko, now entered the Winter Palace.

Bessie Beatty, an American journalist, entered the Winter Palace with the Red Guards: "At the head of the winding staircase groups of frightened women were gathered, searching the marble lobby below with troubled eyes. Nobody seemed to know what had happened. The Battalion of Death had walked out in the night, without firing so much as a single shot. Each floor was crowded with soldiers and Red Guards, who went from room to room, searching for arms, and arresting officers suspected of anti-Bolshevik sympathies. The landings were guarded by sentries, and the lobby was swarming with men in faded uniforms. Two husky, bearded peasant soldiers were stationed behind the counter, and one in the cashier's office kept watch over the safe. Two machine-guns poked their ominous muzzles through the entryway."

Louise Bryant, another journalist commented that there were about 200 women soldiers in the palace and they were "disarmed and told to go home and put on female attire". She added: "Every one leaving the palace was searched, no matter on what side he was. There were priceless treasures all about and it was a great temptation to pick up souvenirs. I have always been glad that I was present that night because so many stories have come out about the looting. It was so natural that there should have been looting and so commendable that there was none."

On 26th October, 1917, the All-Russian Congress of Soviets met and handed over power to the Soviet Council of People's Commissars. Lenin was elected chairman and other appointments included Leon Trotsky (Foreign Affairs) Alexei Rykov (Internal Affairs), Anatoli Lunacharsky (Education), Alexandra Kollontai (Social Welfare), Victor Nogin (Trade and Industry), Joseph Stalin (Nationalities), Peter Stuchka (Justice), Vladimir Antonov-Ovseenko (War), Nikolai Krylenko (War Affairs), Pavlo Dybenko (Navy Affairs), Ivan Skvortsov-Stepanov (Finance), Vladimir Milyutin (Agriculture), Ivan Teodorovich (Food), Georgy Oppokov (Justice) and Nikolai Glebov-Avilov (Posts & Telegraphs).

As chairman of the Council of People's Commissars, Lenin made his first announcement of the changes that were about to take place. Banks were nationalized and workers control of factory production was introduced. The most important reform concerned the land: "All private ownership of land is abolished immediately without compensation... Any damage whatever done to the confiscated property which from now on belongs to the whole People, is regarded as a serious crime, punishable by the revolutionary tribunals."

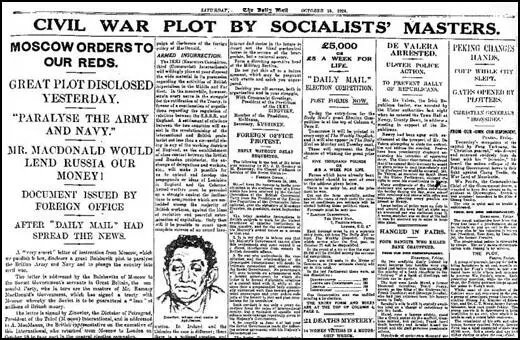

On this day in 1924 the Zinoviev Letter, is published in The Daily Mail. It was just four days before the 1924 General Election. Under the headline "Civil War Plot by Socialists Masters" it argued: "Moscow issues orders to the British Communists... the British Communists in turn give orders to the Socialist Government, which it tamely and humbly obeys... Now we can see why Mr MacDonald has done obeisance throughout the campaign to the Red Flag with its associations of murder and crime. He is a stalking horse for the Reds as Kerensky was... Everything is to be made ready for a great outbreak of the abominable class war which is civil war of the most savage kind."

Dora Russell, whose husband, Bertrand Russell, was standing for the Labour Party in Chelsea, commented: "The Daily Mail carried the story of the Zinoviev letter. The whole thing was neatly timed to catch the Sunday papers and with polling day following hard on the weekend there was no chance of an effective rebuttal, unless some word came from MacDonald himself, and he was down in his constituency in Wales. Without hesitation I went on the platform and denounced the whole thing as a forgery, deliberately planted on, or by, the Foreign Office to discredit the Prime Minister."

Ramsay MacDonald suggested he was a victim of a political conspiracy: "I am also informed that the Conservative Headquarters had been spreading abroad for some days that... a mine was going to be sprung under our feet, and that the name of Zinoviev was to be associated with mine. Another Guy Fawkes - a new Gunpowder Plot... The letter might have originated anywhere. The staff of the Foreign Office up to the end of the week thought it was authentic... I have not seen the evidence yet. All I say is this, that it is a most suspicious circumstance that a certain newspaper and the headquarters of the Conservative Association seem to have had copies of it at the same time as the Foreign Office, and if that is true how can I avoid the suspicion - I will not say the conclusion - that the whole thing is a political plot?"

Bob Stewart claimed that the letter included several mistakes that made it clear it was a forgery. This included saying that Grigory Zinoviev was not the President of the Presidium of the Communist International. It also described the organisation as the "Third Communist International" whereas it was always called "Third International". Stewart argued that these "were such infantile mistakes that even a cursory examination would have shown the document to be a blatant forgery."

The rest of the Tory owned newspapers ran the story of what became known as the Zinoviev Letter over the next few days and it was no surprise when the election was a disaster for the Labour Party. The Conservatives won 412 seats and formed the next government. Lord Beaverbrook, the owner of the Daily Express and Evening Standard, told Lord Rothermere, the owner of The Daily Mail and The Times, that the "Red Letter" campaign had won the election for the Conservatives. Rothermere replied that it was probably worth a hundred seats.

David Low was a Labour Party supporter who was appalled by the tactics used by the Tory press in the 1924 General Election: "Elections have never been completely free from chicanery, of course, but this one was exceptional. There were issues - unemployment, for instance, and trade. There were legitimate secondary issues - whether or not Russia should be afforded an export loan to stimulate trade. In the event these issues were distorted, pulped, and attached as appendix to a mysterious document subsequently held by many creditable persons to be a forgery, and the election was fought on 'red panic' (The Zinoviev Letter)".

After the election it was claimed that two of MI5's agents, Sidney Reilly and Arthur Maundy Gregory, had forged the letter. It later became clear that Major George Joseph Ball, a MI5 officer, played an important role in leaking it to the press. In 1927 Ball went to work for the Conservative Central Office where he pioneered the idea of spin-doctoring. Christopher Andrew, MI5's official historian, points out: "Ball's subsequent lack of scruples in using intelligence for party political advantage while at Central Office in the late 1920s strongly suggests... that he was willing to do so during the election campaign of October 1924."

On this day in 1945 Robert Ley committed suicide. In 1933 Adolf Hitler gave Robert Ley the task of forming the German Labour Front (DAF). Ley, in his first proclamation, stated: "Workers! Your institutions are sacred to us National Socialists. I myself am a poor peasant's son and understand poverty... I know the exploitation of anonymous capitalism. Workers! I swear to you, we will not only keep everything that exists, we will build up the protection and the rights of the workers still further."

During the Second World War Ley was considered an important figure in Hitler's government. W argued on radio on 9th January, 1940, that Ley was "one of the most important members of the Nazi regime". He quoted Ley as saying: "We know that this war is an ideological struggle against world Jewry. England is allied with the Jews against Germany. How low must the English people have fallen to have had as war minister a parasitical and profiteering Jew of the worst kind... England is spiritually, politically and economically at one with the Jews. For us, England and the Jews remain the common foe."

Ley was heavily involved in propaganda. He was quoted in a speech on 24th March, 1940, as saying: "Every German is absolutely certain that Germany will win the war. The British and French are nervous. They've become hysterical, like old women. The Maginot Line is just a piece of junk."

Robert Ley remained in Berlin and according to James P. O'Donnell, the author of The Berlin Bunker (1979) he held regular meetings Adolf Hitler, Joseph Goebbels and Martin Bormann. "Only by sticking around in Berlin, and appealing to Hitler's sympathies, did Ley manage to achieve this late prominence. Hitler knew he was a buffoon, but now he somehow enjoyed Ley's company, especially listening to his ideas for new wonder-weapons."

On 20th October, 1945, Ley with twenty-one others, was indicted by the International Military Tribunal at Nuremberg. He asked Gustave M. Gilbert, the prison psychologist. "How can I prepare a defense? Am I supposed to defend myself against all these crimes which I knew nothing about? Stand us up against the wall and shoot us - you are the victors." On 24th October, he was found dead in his cell. "He had made a noose from the edges of a towel and fastened it to the toilet pipe."

Robert Ley left a suicide note that said: "We have forsaken God, and therefore we were forsaken by God. We put human volition in the place of His godly grace. In anti-Semitism we violated a basic commandment of His creation. Anti-Semitism distorted our outlook, and we made grave errors. It is hard to admit mistakes, but the whole existence of our people is in question; we Nazis must have the courage to rid ourselves of anti-Semitism. We have to declare to the youth that it was a mistake.”