On this day on 16th February

On this day in 1797 Benjamin Parsons, the son of Thomas Parsons and his wife, Anna Stratford Parsons, was born at Nibley in Gloucestershire. He was the youngest child in a family of eight. After attending the parsonage school at Dursley and the grammar school at Wotton under Edge, he was apprenticed for seven years to a tailor at Frampton-on-Severn.

Both his parents were dead by the time he reached the age of fifteen. Three years later he became a Sunday School teacher. He joined the church at Rodborough Tabernacle in 1821. It had originally been established by Selina Shirley, Countess of Huntington. It had "retained its philosophy, which, by promoting a more practical Christianity through good works and deeds, became increasingly relevant to the demands of an industrialising society."

Parsons studied at Cheshunt College before preaching in Swansea for nine months in 1825, and a short stay at Rochdale, in 1826 Parsons was ordained to the Congregational church at Ebley, near Stroud. On 3rd November 1830 he married Amelia Fry. There was no school in the village and Parsons devoted himself to the education of the inhabitants.

Benjamin Parsons was able to reach out to working-class families living in the area. The chapel was extensively refurbished and the congregation was built up from about twenty to well over one thousand worshippers within the space of a few years. Sunday schools were established to cater for over four hundred children.

Paul Hawkins Fisher was someone who watched Benjamin Parsons giving sermons at his chapel. "His complexion was dark, his features irregular but very flexible, his voice powerful; and when excited in speaking his eyes, flashing from beneath his large, black scowling eyebrows, gave fearful effect to his fierce denunciations... In opposing persons or things obnoxious to him."

It has been pointed out: "In many ways he was a natural leader. Gifted intellectually and with considerable oratorical skills, Parsons was able to help the weaker members of society precisely because he had been plunged into and experienced poverty himself. It left an indelible mark on his mind and he never forgot his humble roots. The opportunity of renewed social mobility - moving from lowly artisan to esteemed clergyman - only served to reinforce a personal belief in the power of the Bible as a radical book and that his life's mission was to bring about, on earth, the brotherhood of man."

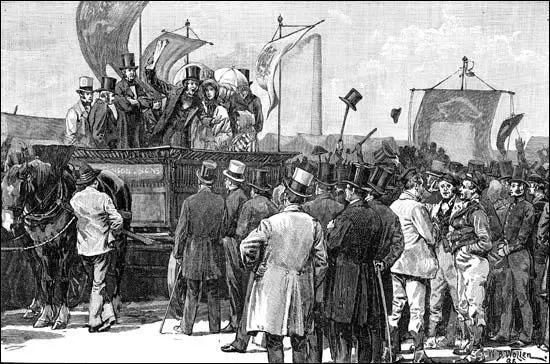

Many working people were disappointed when they realised that the 1832 Reform Act did not give them the vote. This disappointment turned to anger when the reformed House of Commons passed the 1834 Poor Law. In June 1836 William Lovett, Henry Hetherington, John Cleave and James Watson formed the London Working Men's Association (LMWA). Although it only ever had a few hundred members, the LMWA became a very influential organisation. At one meeting in 1838 the leaders of the LMWA drew up a Charter of political demands.

(i) A vote for every man twenty-one years of age, of sound mind, and not undergoing punishment for a crime.

(ii) The secret ballot to protect the elector in the exercise of his vote. (iii) No property qualification for Members of Parliament in order to allow the constituencies to return the man of their choice. (iv) Payment of Members, enabling tradesmen, working men, or other persons of modest means to leave or interrupt their livelihood to attend to the interests of the nation. (v) Equal constituencies, securing the same amount of representation for the same number of electors, instead of allowing less populous constituencies to have as much or more weight than larger ones. (vi) "Annual Parliamentary elections, thus presenting the most effectual check to bribery and intimidation, since no purse could buy a constituency under a system of universal manhood suffrage in each twelve-month period."

When supporters of parliamentary reform held a convention the following year, Lovett was chosen as the leader of the group that were now known as the Chartists. Parsons was very active in the group. The four main leaders of the Chartist movement had been involved in political campaigns for many years and had all experienced periods of imprisonment. Parsons was especially close to Henry Vincent who published a teetotal manifesto that attempted to link chartism with the refusual to drink alcohol. He regarded Vincent as "the most eloquent advocate of the people's rights". He also supported Joseph Sturge, when he established the Complete Suffrage Union, an organisation that promoted class conciliation. He described Sturge as a "real friend of the people".

Benjamin Parsons lectured to the men in the evening, established a night school in the chapel. To support himself and his family he also ran a fee-paying school that was opened in 1840. A militant teetotaller and an active member of the Temperance Society. Parsons also supported the abolition of slavery and the repeal of the Corn Laws. He was also a keen advocate of voluntarism in education.

Benjamin Parsons developed a reputation for holding "extreme opinions" who was so supremely confident in his own ability that he was sometimes considered to be arrogant: "In opposing persons or things obnoxious to him... His manner was bold, undaunted, scornful and decisive... and he employed unsparingly his terrrible powers of sarcasm".

Paul M. Walmsley claims that Parsons was a born teacher who lectured to the people on virtually everything that he read. (12) This included talks on an impressive range of topics from mechanics, chemistry, physiology, history and geography. He also taught controversial topics, such as the French Revolution, the British Constitution. One of his most popular lectures was the Bible as a radical book.

The authors of Friends of the People (2002) have pointed out: "Banjamin Parsons... unquestionably became something of a cult figure in the community. A man possessed of great national ability and strength of character, he was fearless in displaying and defending his own particular convictions. In his sermons, orations and addresses his individuality was often expressed in a charismatic style and with a distinct body language which could have an electrifying effect on audiences."

Benjamin Parsons believed strongly that the minds of girls were equal to those of boys and therefore both sexes should be offered the same educational opportunities at school. In 1842 he published the Mental and Moral Dignity of Women. An advertisement for the book claimed that "in this work the author argues that the mental powers of women are equal and her moral feelings superior, to those of men."

In 1848 Parsons published The Bible and the Six Points of the Charter (1848) where he argued that the Bible provided information that suggested that people should be given the vote. Parsons believed that Chartism was sanctioned by God: "From Genesis to Revelations we have denunciations against the ungodliness of the rich and at the same time the most tender sympathy towards the poor... yet good men are excluded from the polls and parliament because they do not possess certain amount of riches."

Parsons was one of the leaders of the Moral Force Chartists. He argued: "Do it by moral means alone. Not a pike, a blunderbuss, a brick-bat, or a match, must be found in your hands. In physical force your opponents are mightier than you but in moral force you are ten thousand times stronger than they. The best way to prove that you deserve your rights, is to show that you respect the rights of others, and that you will not redress even a wrong by revenge, but by reason and justice alone. Your manner ought to demonstratethat... you have no connection with rudeness or vulgarity."

Feargus O'Connor, the leader of Physical Force group, made speeches where he spoke of being willing "to die for the cause" and promising to "lead people to death or glory". O'Connor argued that the concessions the chartists demanded would not be conceded without a fight, so there had to be a fight. (18) Edwin Paxton Hood claims that Parson's pointed out "the wickedness and vice of Fergus O'Connor and his miserable band of simple dupes and ambitious knaves".

Church leaders became concerned by Parsons' attack on the ruling class: "There is scarcely a law on our statue book which is more iniquitous than the law respecting enclosures. It is brimful of the old aristocratic injustice which framed the Corn Laws and which seems always to proceed on the principle that the poor must be robbed to enrich the rich."

In 1854 Parsons became very ill and was forced into retirement. On 1st August nearly 1,400 people assembled at a tea party given in his honour and in addition to a "purse of three hundred sovereigns" Parsons received £100 that was raised on the day.

Benjamin Parsons died aged 58 on 10th January 1855 and was buried in his own chapel graveyard. On 23rd September 1857 a granite obelisk was erected by public subscription over his grave.

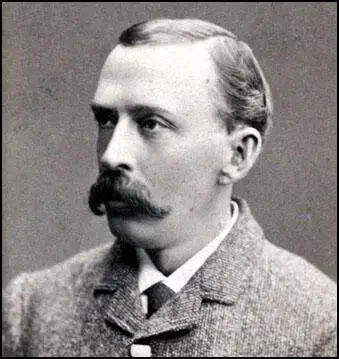

On this day in 1845 journalist George Kennan, the son of Scotch-Irish pioneers, was born in Norfolk, Ohio, on 16th February, 1845. At the age of twelve he left school and found work at the Western Union telegraph office. According to his relative, George Frost Kennan, he was "too frail to serve in uniform" during the American Civil War.

Kennan moved to Cincinnati, where he was appointed to the post of assistant chief operator for Western Union and as military telegrapher for the Associated Press. In 1864, at the age of nineteen, he successfully applied to become a member of an Alaskan-Siberian expedition. The objective being to lay a telegraph line over Alaska and Siberia to connect with the the eastern-most terminus of the Russian telegraph system, at Irkutsk.

On 1st July, 1865, Kennan and three companions set out from San Francisco in a Russian brig. His biographer claims: "Eight weeks later two of them, Kennan and a Russian major, were set ashore at Petropavlovsk, on the Kamchatka Peninsula. Their instructions were to make their way northward through the peninsula to the mainland of eastern Siberia, where they were to explore the two thousand miles of inhospitable territory lying between the Anadyrsk region on the Bering Sea and Nikolayevsk-on-the-Amur and to arrange for the laying of the telegraph line. They were to be picked up a year or so later, after surveying a line and having camps laid out and poles cut for the construction workers who would follow them. Meanwhile they would be on their own. By a combination of good fortune, level-headedness, and physical courage young Kennan, then only twenty years old, survived this ordeal. Dressed like a native, leading the primitive and arduous life of the wandering tribes of that area, traveling at times, for weeks on end, alone with a Yakut dog team through the wastes of one of the world's most forbidding Arctic regions, he completed his assignment. When the relief ship finally arrived, it brought the news that the Atlantic cable had been laid and the entire project had been in vain."

After arriving back in the United States he worked for banks and law offices. Kennan also lectured on his Siberian experiences. Eventually, he moved to Washington where he became night manager of the Associated Press. In 1870 G. P. Putnam's Sons published an account of the Siberian adventures under the title Tent Life in Siberia. According to George Frost Kennan: "It was a creditable literary achievement, especially for a young man without high school or college education. The style, like that of everything Kennan subsequently wrote, was straightforward, clear and disciplined."

On 1st March, 1881, Tsar Alexander II was assassinated by members of the People's Will. The following month Sophia Perovskaya, Andrei Zhelyabov, Nikolai Kibalchich, Nikolai Rysakov, Gesia Gelfman and Timofei Mikhailov were executed for their involvement in the assassination. Others such as Gesia Gelfman, Olga Liubatovich, Anna Yakimova, Vera Figner, Grigory Isaev, Mikhail Frolenko, Tatiana Lebedeva and Anna Korba were exiled to Siberia.

Kennan attempted to obtain sponsorship for and on-the-spot study of Siberia and the exile system. After approaching several organizations he eventually persuaded Century Magazine to finance the expedition. After a preliminary visit to St. Petersburg and Moscow to perfect the arrangements, Kennan set off on his journey in the early spring of 1885, accompanied by the artist, George Albert Frost. "We both spoke Russian, both had been in Siberia before, and I was making to the empire my fourth journey."

The account of the journey appeared serially, in the years 1888-89, in Century Magazine. In an early article he explained the tradition of sending criminals to Siberia. "Russian exiles began to go to Siberia very soon after its discovery and conquest - as early probably as the first half of the seventeenth century. The earliest mention of exile in Russian legislation is in a law of the Tsar Alexei Mikhailovich in 1648. Exile, however, at that time, was regarded not as a punishment in itself, but as a means of getting criminals who had already been punished out of the way. The Russian criminal code of that age was almost incredibly cruel and barbarous. Men were impaled on sharp stakes, hanged, and beheaded by the hundred for crimes that would not now be regarded as capital in any civilized country in the world; while lesser offenders were flogged with the knut and bastinado, branded with hot irons, mutilated by amputation of one or more of their limbs, deprived of their tongues, and suspended in the air by hooks passed under two of their ribs until they died a lingering and miserable death."

Kennan explained that it was the case of Vera Zasulich when she tried to assassinate Dmitry Trepov, the Governor General of St. Petersburg, that encouraged Tsar Alexander II to send political prisoners to Siberia. This included those distributing political propaganda to the peasants. "They... did not resort to violence in any form, and did not even make a practice of resisting arrest, until after the Government had begun to exile them to Siberia for life with ten or twelve years of penal servitude, for offenses that were being punished at the very same time in Austria with only a few days - or at most a few weeks - of personal detention. It was not terrorrism that necessitated administrative exile in Russia; it was merciless severity and banishment without due process of law that provoked terrorism."

Kennan interviewed several of those political prisoners. This included Anna Korba a member of the People's Will. "In 1877 the Russo-Turkish War broke out, and opened to her ardent and generous nature a new field of benevolent activity. As soon as wounded Russian soldiers began to come back from Bulgaria, she went into the hospitals of Minsk as a Sister of Mercy, and a short time afterward put on the uniform of the International Association of the Red Cross, and went to the front and took a position as a Red Cross nurse in a Russian field-hospital beyond the Danube. She was then hardly twenty-seven years of age. What she saw and what she suffered in the course of that terrible Russo-Turkish campaign can be imagined by those who have seen the paintings of the Russian artist Vereshchagin. Her experience had a marked and permanent effect upon her character. She became an enthusiastic lover and admirer of the common Russian peasant, who bears upon his weary shoulders the whole burden of the Russian state, but who is cheated, robbed, and oppressed, even while fighting the battles of his country. She determined to devote the remainder of her life to the education and the emancipation of this oppressed class of the Russian people. At the close of the war she returned to Russia, but was almost immediately prostrated by typhus fever contracted in an overcrowded hospital. After a long and dangerous illness she finally recovered, and began the task that she had set herself; but she was opposed and thwarted at every step by the police and the bureaucratic officials who were interested in maintaining the existing state of things, and she gradually became convinced that before much could be done to improve the condition of the common people the Government must be overthrown. She... participated actively in all the attempts that were made between 1879 and 1882 to overthrow the autocracy and establish a constitutional form of government." She was arrested and found guilty of carrying out propaganda activities and was sent to the Kara Prison Mines in Siberia.

Kennan carried out a long interview with Prince Alexander Kropotkin, the brother of Prince Peter Kropotkin. Kennan pointed out that: "Prince Alexander Kropotkin's... views with regard to social and political questions would have been regarded in America, or even in western Europe, as very moderate, and he had never taken any part in Russian revolutionary agitation. He was, however, a man of impetuous temperament, high standard of honor, and great frankness and directness of speech; and these characteristics were perhaps enough to attract to him the suspicious attention of the Russian police."

Kropotkin told Kennan: "I am not a nihilist nor a revolutionist and I never have been. I was exiled simply because I dared to think, and to say - what I thought, about the things that happened around me, and because I was the brother of a man whom the Russian Government hated." His first arrest was as a result of having a copy of a book, Self-Reliance, by Ralph Waldo Emerson. Kennan had great respect for Kropotkin and was distressed when he heard about how he committed suicide while in exile in 1890.

In 1891 his articles were published in book form under the title Siberia and the Exile System. The book appeared illegally in Russia and according to George Frost Kennan: "The gratitude of the entire opposition movement-moderates and extremists alike - went out to him for his profound understanding and effective public sponsorship of the opposition cause."

Kennan served as a war correspondent in the Spanish-American War and the Russo-Japanese War. When Tsar Nicholas II abdicated he gave his support to the Provisional Government led by Prince George Lvov and Alexander Kerensky. He disapproved of the Bolshevik Revolution but argued against USA intervention in the Russian Civil War.

George Kennan died in 1924.

On this day in 1870 trade unionist Leonora O'Reilly, the daughter of Irish immigrants, was born in New York City. The family were poor and at the age of eleven she began working in a collar factory. Five years later she joined the Knights of Labor.

O'Reilly became active in trade union activities and eventually helped form a female chapter of the United Garment Workers of America. She also continued her academic education by attending the Brooklyn Pratt Institute. Later she taught at the Manhattan Trade School for Girls (1902-09).

O'Reilly was also involved in the formation of the Woman's Trade Union League. The main objective of the organization was to educate women about the advantages of trade union membership. It also support women's demands for better working conditions and helped to raise awareness about the exploitation of women workers.

The Woman's Trade Union League received support from the American Federation of Labour and attracted women concerned with women's suffrage as well as industrial workers wanting to improve their pay and conditions. Early members included Jane Addams, Lillian Wald, Margaret Robins, Mary McDowell, Mabel Gillespie, Margaret Haley, Helen Marot, Mary Ritter Beard, Rose Schneiderman, Alice Hamilton, Agnes Nestor, Eleanor Roosevelt, Florence Kelley and Sophonisba Breckinridge.

O'Reilly developed a reputation as an outstanding orator. The New York Call reported in 1909: "Miss O'Reilly was simply attired, modest in appearance and unassuming in her manners. But no sooner did she begin to speak when her voice, her face, her very personality, told of a sincerity that won admiration. She gained the audience with the beginning of her first sentence. In addition to her sincerity she is eloquent and humorous. In simple words but in a decided tone, she hit hard at her opponents, and said words that impressed the most obdurate."

O'Reilly played a leading role in the garment workers dispute (1909-10) and led the investigation into the fire at the Triangle Shirtwaist Company that resulted in the death of 146 people. O'Reilly, who campaigned for woman suffrage and the Wage Earners' League and was active in the Henry Street Settlement House, was also a member of the Socialist Party of America and National Association for the Advancement of Colored People.

Leonora O'Reilly, the daughter of Irish immigrants, was born in New York City on 16th February 1870. The family were poor and at the age of eleven she began working in a collar factory. Five years later she joined the Knights of Labor.

O'Reilly became active in trade union activities and eventually helped form a female chapter of the United Garment Workers of America. She also continued her academic education by attending the Brooklyn Pratt Institute. Later she taught at the Manhattan Trade School for Girls (1902-09).

O'Reilly was also involved in the formation of the Woman's Trade Union League. The main objective of the organization was to educate women about the advantages of trade union membership. It also support women's demands for better working conditions and helped to raise awareness about the exploitation of women workers.

The Woman's Trade Union League received support from the American Federation of Labour and attracted women concerned with women's suffrage as well as industrial workers wanting to improve their pay and conditions. Early members included Jane Addams, Lillian Wald, Margaret Robins, Mary McDowell, Mabel Gillespie, Margaret Haley, Helen Marot, Mary Ritter Beard, Rose Schneiderman, Alice Hamilton, Agnes Nestor, Eleanor Roosevelt, Florence Kelley and Sophonisba Breckinridge.

O'Reilly developed a reputation as an outstanding orator. The New York Call reported in 1909: "Miss O'Reilly was simply attired, modest in appearance and unassuming in her manners. But no sooner did she begin to speak when her voice, her face, her very personality, told of a sincerity that won admiration. She gained the audience with the beginning of her first sentence. In addition to her sincerity she is eloquent and humorous. In simple words but in a decided tone, she hit hard at her opponents, and said words that impressed the most obdurate."

O'Reilly played a leading role in the garment workers dispute (1909-10) and led the investigation into the fire at the Triangle Shirtwaist Company that resulted in the death of 146 people. O'Reilly, who campaigned for woman suffrage and the Wage Earners' League and was active in the Henry Street Settlement House, was also a member of the Socialist Party of America and National Association for the Advancement of Colored People.

Leonora O'Reilly died on 3rd April 1927.

On this day in 1871 Arthur Ponsonby, the son of Sir Henry Ponsonby (1825–1895), Private Secretary to Queen Victoria, was born in Windsor Castle on 16th February 1871. After being educated at Eton and Balliol College (1890-92), he went abroad to learn German and French and in 1894 entered the Diplomatic Service and worked in Constantinople and Copenhagen before moving to the Foreign Office in 1900.

Ponsonby married Dorothea Parry, the daughter of the composer Charles Hubert Hastings Parry. They set up home at Shulbrede Priory in Linchmere and Dorothea gave birth to Elizabeth (1900) and Matthew (1904).

A member of the Liberal Party Ponsonby resigned from the Foreign Office in 1902 in order to further a career in politics. He served first in the Liberal Central Association office and then in 1906, after defeat at Taunton in the 1906 General Election, was appointed principal private secretary to the prime minister, Henry Campbell-Bannerman. When Campbell-Bannerman died in 1908, Ponsonby won the resulting by-election for the Stirling Burghs. As his biographer, Raymond A. Jones has pointed out: "He achieved notoriety almost immediately after his election by voting against the king's proposed visit to Russia and in consequence found himself excluded from the guest list of the king's garden party. This storm in a teacup established Ponsonby as a radical, opposed to Liberal Imperialism."

While in the House of Commons Ponsonby moved to the left, this was reflected in his books, The Camel and the Needle's Eye (1910) and The Decline of the Aristocracy (1912). Ponsonby became a pacifist and campaigned against an increase in defence spending.

A strong critic of the foreign policy of Herbert Asquith and Sir Edward Grey, Ponsonby was opposed to Britain's involvement in the First World War. Ponsonby joined with Charles Trevelyan, E.D. Morel, George Cadbury, Ramsay MacDonald, Arthur Ponsonby, Arnold Rowntree to form the Union of Democratic Control (UDC). Over the next couple of years the UDC became the leading anti-war organisation in Britain.

Like other anti-war MPs, Arthur Ponsonby was defeated in the 1918 General Election. Ponsonby joined the Labour Party and in the 1922 General Election became the MP for the Brightside division of Sheffield.

In 1925 Ponsonby published a statement of his beliefs, Now is the Time, and launched a petition committing its signatories to "refuse to support or render war service to any Government which resorts to arms". After two years he was able, in a deputation to Stanley Baldwin in December 1927, to present a petition signed by 128,770 people. The following year he published Falsehood in Wartime (1928), which exposed many atrocity stories of the First World War as propaganda lies. Ponsonby insisted "that all disputes between nations are capable of settlement either by diplomatic negotiations or by some form of international arbitration".

After the 1929 General Election, Ramsay MacDonald appointed Ponsonby as Parliamentary Secretary to the Ministry of Transport. The following year Ponsonby was granted a peerage and became Leader of the House of Lords (1930-1935). During this period Ponsonby became the leader of the peace movement in Britain. Martin Ceadel, the author of Pacifism in Britain 1914-1945 (1980) has argued: "The reason for Ponsonby's sudden emergence as the leading British pacifist of the later twenties and early thirties was his belief that he had discovered a new type of pacifism which was both commonsensical in outlook and irrefutable in inspiration."

Arthur Ponsonby joined Richard Sheppard, a canon of St. Paul's Cathedral, to establish the Peace Pledge Union in July 1935. The organization included other prominent religious, political and literary figures including George Lansbury, Vera Brittain, Siegfried Sassoon, Donald Soper, Aldous Huxley, Laurence Housman and Bertrand Russell.

Ponsonby collaborated with George Lansbury in the War Resisters' International, and supported disarmament in opposition to Labour's official policy of collective security. This policy difference led him in September 1935 to resign the leadership of the Labour Party in the House of Lords.

From 1937 the PPU organized alternative Remembrance Day commemorations, including the wearing of white rather than red poppies on 11th November. In 1938 the Peace Pledge Union campaigned against legislation introduced by Parliament for air raid precautions, and the following year against legislation for military conscription.

On the outbreak of the Second World War Ponsonby virtually withdrew from active politics. He resigned from the Labour Party on 15th May 1940 as he opposed to its decision to join the National Government formed by Winston Churchill. Ponsonby suffered an incapacitating stroke in September 1943 from which he never recovered.

Lord Ponsonby of Shulbrede died at the Heather Bank Nursing Home in Hindhead on 23rd March 1946.

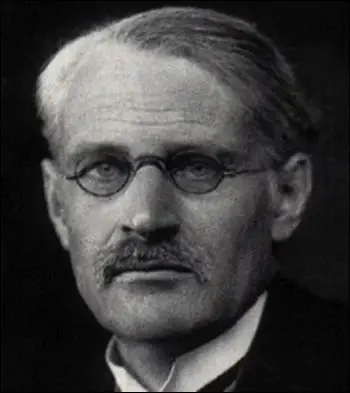

On this day in 1876 George Macaulay Trevelyan, the son of the Liberal politician, George Otto Trevelyan, was born in Stratford-on-Avon. His grandfather Sir Charles Edward Trevelyan was a reforming civil servant. His mother, Caroline Philips, was the daughter of Robert Needham Philips, who was also a member of the House of Commons.

George had two brothers, Charles Trevelyan and Robert Trevelyan. He later claimed that their childhood was very political. He described how "a sense of drama of English and Irish history was purveyed to me through daily sights and experiences, with my father as commentator and bard."

The three boys spent a lot of time playing with their toy soldiers where they replayed famous battles. "Much of our pocket money must have gone towards purchasing those exquisitely packed cardboard boxes, each containing twenty or thirty infantrymen... all moulded, packed and painted at Nuremberg. Even now I sometimes dream of discovering and pillaging marvellous magic toy shops, rich with countless boxes of the oldest and best soldiers, and most precious of all, artillery - canon, gunners."

At an early age he discovered his great-uncle was the historian, Thomas Babington Macaulay. She used to read him passages from his book, History of England. "I remember so well Mama reading it to me for the first time when I was a little boy; it was in the library, and I used to lie with my head on the woolly rug against the fire and look up at the marble head carved on the mantelpiece, while she read."

Trevelyan was educated at Harrow and Trinity College, where he studied history. He also developed a strong interest in literature and politics. He wrote to his mother that "I live in literature, politics and history, and am burning for the world (be it only Cambridge).

Beatrice Webb met him for the first time in 1895: "He (George Macaulay Trevelyan) is bringing himself up to be a great man, is precise and methodical in all his ways, ascetic and regular in his habits, eating according to rule, exercising according to rule... he is always analysing his powers, and carefully considering how he can make the best of himself. In intellectual parts, he is brilliant, with a wonderful memory, keen analytical power, and a vivid style. in his philosophy of life, he is, at present, commonplace, but then he is young - only nineteen."

While at the University of Cambridge was soon elected to the Apostles, the university's most exclusive and influential undergraduate society. Other members included Lytton Strachey, E. M. Forster, Roger Fry, Leonard Wolff, George Edward Moore, Goldsworthy Lowes Dickinson and Desmond MacCarthy. His contemporaries included John Maynard Keynes, Bertrand Russell and Ralph Vaughan Williams.

George Macaulay Trevelyan was a puritan and strongly disapproved of the homosexuality of some of the Apostles. Strachey complained about his moral views: "Trevy... at once launched into lecture after lecture. It was truly awful. Everything he said was stupid and rude to such a painful degree! In addition to all the old ordinary horrors, he has now become curiously numb and dumb... I believe he's disappointed, almost embittered."

Although he rejected homosexual relations that had became widespread for a time among some Apostles, he did absorb their culture of radical agnosticism. According to his biographer, David Cannadine, Trevelyan remained all his life loyal to a secular version of Christian ethics: "a love of things good, and a hatred of things evil". In 1896 he obtained a first in the historical tripos, and soon after he was elected a fellow of Trinity.

In 1896 he obtained a first in the historical tripos, and soon after he was elected a fellow of Trinity College. The following year he completed his first book, England in the Age of Wycliffe (1899) that dealt with the Peasants' Revolt. Soon afterwards he gave up his fellowship. As he had a large private income he did not have to be a professional historian. Instead he was able to write his books independently. He also taught part-time at the Working Men's College in London.

George Macaulay Trevelyan published England under the Stuarts in 1904. Cannadine has described the book as "an outstandingly successful general survey, which unfolded the familiar story of the civil war and the revolution of 1688 in more disciplined prose and mature style. As he interpreted it, the seventeenth century witnessed fundamental advances in religious toleration and parliamentary freedom, the forces of Catholic despotism were vanquished, and Great Britain gradually evolved towards the status of a world power".

In 1904 he married Janet Penrose Ward, the daughter of the novelist Mary Augusta Ward and Thomas Humphry Ward, a journalist. She was the great niece of the poet Matthew Arnold, and the great granddaughter of Dr Thomas Arnold, the reforming headmaster of Rugby School. The couple moved to Cheyne Gardens in Chelsea and Janet had three children, Mary Caroline (1905), Theodore Macaulay (1906), who died from appendicitis in 1911, and Charles Humphry (1909).

George's brother, Charles Trevelyan, was adopted as the Liberal Party parliamentary candidate for North Lambeth, but was narrowly defeated in the 1895 General Election. The following year he argued that he was attracted to the philosophy of socialism. "I have the greatest sympathy with the growth of the socialist party. I think they understand the evils that surround us and hammer them into people's minds better than we Liberals. I want to see the Liberal party throw its heart and soul fearlessly into reform so as to prevent a reaction from the present state of thugs and the violent revolution that would inevitably follow it."

Family influence enabled him to being adopted for the constituency of Elland, and entered parliament after a by-election in March 1899. Charles Trevelyan was a very independent member of the House of Commons and took George's advice: "It is a rule that no Trevelyan ever sucks up either to the press, or the chiefs, or the 'right people'. The world has given us money enough to enable us to do what we think is right. We thank it for that and ask no more of it, but to be allowed to serve it."

George Macaulay Trevelyan was more interested in writing history than politics. According to David Cannadine: "His great work was his Garibaldi trilogy (1907–11), which established his reputation as the outstanding literary historian of his generation. It depicted Garibaldi as a Carlylean hero - poet, patriot, and man of action - whose inspired leadership created the Italian nation. For Trevelyan, Garibaldi was the champion of freedom, progress, and tolerance, who vanquished the despotism, reaction, and obscurantism of the Austrian empire and the Neapolitan monarchy. The books were also notable for their vivid evocation of landscape, for their innovative use of documentary and oral sources, and for their spirited accounts of battles and military campaigns."

Garibaldi and the Making of Italy was published in September 1911 and sold 3,000 copies in a few days. John H. Plumb attempted to explain the success of the book. "These were the years of the greatest liberal victory in English politics for a generation. The intellectual world responded to the optimism of the politicians... The Garibaldi story fitted these moods." Plum went on to argue that Trevelyan wrote like a poet. "Having read (Trevelyan's work), who could doubt that here was a great artist at work; at work in a medium, the writing of history, in which scholars have been plentiful and artists rare. But why did Trevelyan choose to use his gift of imagination in history rather than poetry?"

Other historians were not so impressed with Trevelyan's work. Stefan Collini argues that Trevelyan was a deeply flawed historian. "Trevelyan was able to write with an easy familiarity about the families who had for so long ruled England, and yet in some ways his inherited sense of his destiny was a handicap: there were certain kinds of questions it didn't dispose him to ask... he was not prompted to be critically reflective about the assumptions and concepts he brought to the writing of history. In an important sense, Trevelyan was not an intellectual."

At the end of July, 1914, it became clear to the British government that the country was on the verge of war with Germany. Four senior members of the government, Charles Trevelyan, David Lloyd George, John Burns and John Morley, were opposed to the country becoming involved in a European war. They informed the Prime Minister, Herbert Asquith, that they intended to resign over the issue. When war was declared on 4th August, three of the men, Trevelyan, Burns and Morley, resigned, but Asquith managed to persuade Lloyd George, his Chancellor of the Exchequer, to change his mind.

The anti-war newspaper, The Daily News, commented: "Among the many reports which are current as to Ministerial resignations there seems to be little doubt in regard to three. They are those of Lord Morley, Mr. John Burns, and Mr. Charles Trevelyan. There will be widespread sympathy with the action they have taken. Whether men approve of that action or not it is a pleasant thing in this dark moment to have this witness to the sense of honour and to the loyalty to conscience which it indicates... Mr. Trevelyan will find abundant work in keeping vital those ideals which are at the root of liberty and which are never so much in danger as in times of war and social disruption."

In a letter to his constituents Charles Trevelyan explained his reasons for resignation: "However overwhelming the victory of our navy, our commerce will suffer terribly. In war too, the first productive energies of the whole people have to be devoted to armaments. Cannon are a poor industrial exchange for cotton. We shall suffer a steady impoverishment as the character of our work exchanges. All this I felt so strongly that I cannot count the cause adequate which is to lead to this misery. So I have resigned."

At first George supported his brother's actions. Julian Huxley recalled that George "buried his head on his hands on the breakfast table, and looked up weeping". He told Huxley "millions of human beings are going to be killed in this senseless business". However, once the war started, he reluctantly decided to support the war. This brought him into direct conflict with Charles Trevelyan.

George wrote to Charles, three days after the war was declared: "I wish to see no-one crushed, neither France, Belgium nor Germany... So now that war has come, which I wish we had avoided, I support the war not merely from the point of view of our own survival but because I think German victory will probably be the worst thing for Europe, at any rate her victory in the West."

A week later George wrote to Charles again. "You will be all the more effective for peace when the time comes if you show patriotism now and don't make yourselves widely unpopular... You have of all people made your position clear, and sacrificed for it... anything you can now do or say to show you are backing the war, as we are in it, will make you the more effective for peace when the time comes."

Charles Trevelyan rejected this advice. As A. J. A. Morris has pointed out, it was clear to him that "Britain was condemned to war for no better reason than sentimental attachment to France and hatred of Germany. Trevelyan resigned from the government in protest. By this action he found himself estranged from most of his family, condemned and vilified by a hysterical press, and rejected by his constituency association."

The Daily Sketch launched a personal attack on Trevelyan accusing him of being pro-German: "Trevelyan would then have a very congenial atmosphere - in the Reichstag. We have no time to listen to his foolish and pernicious talk. It is a scandal that he should be in Parliament when he continues to preach these pro-German and utterly impracticable pacifist doctrines. Trevelyan must go".

George Macaulay Trevelyan was also highly critical of his brother. "I know that wisdom may begin to come to poor human beings through misery. But even I doubt when I see people like George carried away by shallow fears and ill-informed hatreds... It shows how absurdly far we are from brotherly feeling to foreigners when even in him it is a shallow veneer. He like all the rest wants to hate the Germans... I am more discouraged by it than anything else because it shows the helplessness of intellect before national passion."

George Trevelyan supported the war effort as he was convinced that Kaiser Wilhelm II was a despot that needed to be defeated. His defective eyesight meant he was unfit for military service, and so in 1915 he became commandant of the first British Red Cross ambulance unit to be sent to Italy. He spent the next three years transporting wounded soldiers to hospitals behind the lines.

He explained his thoughts on the war in a letter he wrote to his father in May, 1917. "We are in the third day and night of the biggest battle we have had yet, and likely to be the most prolonged. It is a great pleasure to be in the fullness of activity and adventure day after day and night after night. Both in Gorizia and also in the high hills such scenes of beauty and romance as this big war in the mountains are wonderful indeed. It is a great life for me, rushing about from front to front and now and then to the base along this thirty miles of mountain battle. No one can have a pleasanter part in it."

Trevelyan recorded his experiences in the First World War in Scenes from Italy's War (1919). The following year he finally completed his long awaited book on Earl Grey entitled Lord Grey of the Reform Bill (1920). This was followed by British History in the Nineteenth Century (1922) and Manin and the Venetian Revolution of 1848 (1923).

During this period he decided he would write a patriotic history of England. He told his father, George Otto Trevelyan: "In this age of democracy and patriotism, I feel strongly drawn to write the history of England as I feel it, for the people... The war has cleared my mind of some party prejudices or points of view and I feel as if I have a conception of the development of English history, liberal but purely English and embracing the other elements. It might be a success as a literary work (otherwise I would not touch it). The doubt in my mind is whether it could have elbow room to be a literary success without being so long as to prevent the wide popularity which would alone justify the choice of it."

Trevelyan's highly popular, History of England, was published in 1926. This book took a less partisan view of politics than his earlier writings. "Trevelyan had resolved to write such a book during the First World War as a celebration of, and thank-offering to, the English people. In it he set out the essential elements of the nation's evolution and identity: parliamentary government, the rule of law, religious toleration, freedom from continental interference or involvement, and a global horizon of maritime supremacy and imperial expansion".

Trevelyan's new political views were criticised by other historians. Geoffrey Elton denounced him as a "not very scholarly writer" who produced "soothing pap... lavishly doled out... to a large public". (29) John P. Kenyon complains that Trevelyan was an "insufferable snob" with "socially retrograde views". J. C. D. Clark suggests that Trevelyan was guilty of "shallowness" and "superficiality".

By this time he had abandoned the Liberal Party for the Conservative Party. Whereas his brother, Charles Trevelyan, was now a leading member of the Labour Party. The author of A Very British Family: The Trevelyans (2006) has claimed that "George's wartime adventures had changed him". His biographer has argued that his history writing reflected a change in his political opinions: "Trevelyan had a very strong sense of national identity and he wrote his books in part because he had that sense of identity but he also wrote his books to promote that sense of national identity... He believed history had a social and political purpose and on the whole it was to reinforce a sense of identity and belonging rather than to subvert it."

In 1927, Stanley Baldwin, the Conservative Prime Minister, appointed George Macaulay Trevelyan regis professor of modern history at University of Cambridge. Professional success was accompanied by personal wealth following the death of his parents in 1928. Charles inherited Wallington Hall whereas George became the owner of a large house and estate at Hallington Hall in Northumberland. "George used his considerable new-found wealth to buy up beautiful and historic places in England's threatened landscape."

George Macaulay Trevelyan published a series of history books. This included Blenheim (1930), The Calls and Claims of Natural Beauty (1931), Ramillies and the Union with Scotland (1932), The Peace and the Protestant Succession (1934), Sir George Otto Trevelyan: A Memoir (1932), Grey of Fallodon (1937) and The English Revolution, 1688–1698 (1938).

In the 1930s Trevelyan became concerned about the rise of Adolf Hitler and Nazi Germany. But as a supporter of Stanley Baldwin and Neville Chamberlain, he argued for appeasement: "Although he admired Winston Churchill as a writer and historian, he had no time for Churchill's views on India, Germany, or Edward VIII, and he was a firm supporter of the Munich settlement. But he had little doubt that another war with Germany would come, and that whatever the result, a second such conflict in his lifetime would spell the end of the world as he had known it."

In October 1939, he wrote to his brother, Robert Trevelyan, about his feelings about the inevitable outbreak of the Second World War. "The last thing Edward Grey (the Foreign Secretary at the outbreak of the First World War) said to me in the few weeks between the Nazi revolution and his death was, 'I see no hope for the world'. There is less now. One half of me suffers horribly, the other half is detached, because the 'world' that is threatened is not my world, which died years ago. I am a mere survivor. Life has been a great gift for which I am grateful, though I would gladly give it back now."

George Macaulay Trevelyan spent the early years of the war writing, English Social History: A Survey of Six Centuries. He told his daughter that he wanted to write a history of England that took into account the lives of our ancestors in a way that did not depend on "the well known names of Kings, Parliaments and wars", but instead moved "like an underground river, obeying its own laws or those of economic change, rather than following the direction of political happenings that move on the surface of life".

The book could not be published in England until 1942, because of wartime paper shortages. After seven years it sold nearly 400,000 copies. John H. Plumb argued that the book appeared just at the right time: "The war... had jeopardized the traditional pattern of English life, and in some ways destroyed it forever. This created among all classes a deep nostalgia for the way of life which we were losing. Then, again, the war had made conscious to millions that our national attitude to life was historically based, the result of centuries of slow growth, and that it was for the old, tried ways of life for which we were fighting. Winston Churchill, in his great war speeches made us all conscious of our past, as never before. And in this war, too, there were far more highly educated men and women in all ranks of all the services. The twenties and thirties of this century had witnessed a great extension of secondary school education, producing a vast public capable of reading and enjoying a book of profound historical imagination, once the dilemma of their time stirred them to do so."

During the last few years of his life Trevelyan's scholarly reputation went into a prolonged decline among professional academics. However, he was liked by Conservative politicians and Winston Churchill described Trevelyan as "one of our foremost national figures". The Times commented that like his great-uncle, Thomas Babington Macaulay he was "the accredited interpreter to his age of the English past".

George Macaulay Trevelyan died at his home in Cambridge on 20th July 1962.

On this day in 1904 George Kennan was born in Milwaukee, Wisconsin. After graduating from St John's Military Academy he studied history at Princeton University. In 1926, Kennan joined the foreign service and was appointed as vice-consul in Geneva. This was followed by posts to Berlin, Tallinn and Riga. Kennan was being trained as an expert on the Soviet Union and in 1929 was sent to the study Russian at the University of Berlin.

In November, 1933, Franklin D. Roosevelt established diplomatic relations with the Soviet Union. William C. Bullitt was appointed as United States ambassador, and Kennan became third secretary at the embassy in Moscow. After two years in the Soviet Union he was assigned to Vienna. This was followed by spells in Prague and Berlin.

George Kennan was opposed to the idea that the United States should appear to be supporting the Soviet Union against Germany. He feared this would identify the United States "with the Russian destruction of the Baltic states, with the attack against Finnish independence, with the partitioning of Poland... and with the domestic policy of a regime which is widely feared and detested throughout this part of the world".

The bombing of Pearl Harbor, brought America into the Second World War. Kennan was still in Nazi Germany at the time and he was interned. In April 1942 Kennan was released and was reassigned to Lisbon in Portugal. At the time this was a notorious centre of international espionage. In 1944 Kennan returned to the Soviet Union where he took up the post of minister-counsellor and chargé d'affaires.

George Kennan remained critical of the actions of Joseph Stalin. This included the decision by Stalin not to order the Red Army to support the Warsaw Uprising against the German Army in 1944. Kennan reported to Franklin D. Roosevelt that he should have a "thorough-going exploration of Soviet intentions with regard to the future of the remainder of Europe".

After the war Kennan returned to the United States where George Marshall appointed him as director of the State Department's policy-planning staff. Over the next couple of years Kennan developed the foreign policy of containment. Kennan argued that communist influence should be contained within existing territorial limits, either by armed intervention or, more often, by economic and technical assistance.

On 22nd February, 1946, Kennan sent a series of five telegrams to President Harry S. Truman. This eventually became known as the Long Telegram. It included the following passage: "At the bottom of the Kremlin's neurotic view of world affairs is traditional and instinctive Russian sense of insecurity. Originally, this was insecurity of a peaceful agricultural people trying to live on vast exposed plain in neighborhood of fierce nomadic peoples. To this was added, as Russia came into contact with economically advanced West, fear of more competent, more powerful, more highly organized societies in that area."

The following year Kennan advocated direct military intervention in Italy: "This would admittedly result in much violence and probably a military division of Italy but it might well be preferable to a bloodless election victory, unopposed by ourselves, which would give the Communists the entire peninsula at one coup and send waves of panic to all surrounding areas." As Frances Stonor Saunders points out in Who Paid the Piper: The CIA and the Cultural Cold War? (1999): "Truman, fortunately, didn't go along with this precipitate suggestion, but he did authorize covert intervention in the Italian elections instead."

Kennan wrote an anonymous article in the Foreign Affairs magazine in July 1947, where he argued that the Soviet Union was fundamentally opposed to coexistence with the West and desired a world-wide extension of the Soviet system. However, Kennan argued that communism could be contained if the West showed determined opposition to their expansion plans. Kennan's ideas subsequently became the core of United States policy towards the Soviet Union and was reflected in both the Truman Doctrine and the European Recovery Program (ERP).

Kennan's views had a tremendous influence of a group of important political figures based in Washington. Known as the Georgetown Crowd, it included figures such as Dean Acheson, Frank Wisner, Joseph Alsop, Philip Graham, Katharine Graham, David Bruce, Clark Clifford, Walt Rostow, Eugene Rostow, Chip Bohlen and Paul Nitze.

Kennan was a strong supporter of the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) that was established in September 1947. Its role was to evaluate intelligence reports and coordinate the intelligence activities of the various government departments in the interest of national security. Frank Wisner remained concerned about the spread of communism and began lobbying for a new intelligence agency. He gained support for this from James Forrestal, the Defense Secretary. In June 1948, Kennan, drafted a directive that resulted in the Office of Special Projects.

Wisner was appointed director of the organization. Soon afterwards it was renamed the Office of Policy Coordination (OPC). This became the espionage and counter-intelligence branch of the Central Intelligence Agency. Wisner was told to create an organization that concentrated on "propaganda, economic warfare; preventive direct action, including sabotage, anti-sabotage, demolition and evacuation measures; subversion against hostile states, including assistance to underground resistance groups, and support of indigenous anti-Communist elements in threatened countries of the free world".

In 1949 Kennan clashed with John Foster Dulles over the issue of the recognizing communist China. Dulles leaked the story to a journalist and Kennan decided to resign from his policy planning post. He joined the Institute for Advanced Study at Princeton but in 1952 Harry S. Truman appointed Kennan as the United States ambassador in Moscow.

On his return to Washington Kennan became critical of the foreign policies of President Dwight Eisenhower. Kennan opposed the formation of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) and claimed that developments in Korea and Vietnam sprang from nationalism rather than Marxism. Senator Joseph McCarthy denounced Kennan as "a commie lover". John Foster Dulles contacted Kennan and told him he was no longer wanted by the administration. Ironically, his brother, Allen Dulles, offered him a job with the CIA. Kennan refused and decided to become an academic.

In 1956 Kennan was appointed as professor of historical studies at the Princeton Institute and while there revised his views on containment. Kennan now advocated a program of disengagement from areas of conflict with the Soviet Union. He remained at Princeton until John F. Kennedy appointed Kennan as the United States ambassador to Yugoslavia (1961-63).

Books by Kennan include the Realities of American Foreign Policy (1954), Russia Leaves the War (1956), Memoirs: 1925-1950 (1967), Russia and the West (1967), The Nuclear Delusion (1982) American Diplomacy, 1900-50 (1985), Soviet-American Relations, 1917-1920 (1989), Around the Cragged Hill: A Personal and Political Philosophy (1993) and At a Century's Ending: Reflections, 1982-95 (1997).

George Kennan died on 17th March, 2005.

On this day in 1907 Barbara Nixon was born in Churchdown, Gloucestershire. She studied English at Newnham College. During her time at Cambridge University Barbara met the academic, Maurice Dobb, who she married in 1931.

Dobb was a long-term member of the Communist Party of Great Britain but Nixon was active in the Labour Party and held a seat on London County Council while pursuing a career in acting. Nixon appeared in 1066: And All That (1939). She also wrote plays and O Mistress Mine was produced in 1939.

In May, 1940, she became a volunteer part-time Air Raid Warden (ARP) in Finsbury. Nixon kept a diary during the war and on Saturday 7th September, 1940, she described the first German bombing raid on London that later was described as the Blitz, when 300 German bombers and 600 escorting fighters arrived over London. Although four miles away she could see that the people in "the East End were getting it... we could see the miniature silver planes circling round and round the target area in such perfect formation that they looked like a children's toy model of flying boats or chair-o-planes at a fair... Presently we saw a white cloud rising; it looked like a huge evening cumulus, but it grew steadily, billowing outwards and always upwards... The cloud grew to such a size that we gasped incredulously; there could not ever in history have been so gigantic a fire."

Barbara Nixon saw her first bomb victim soon afterwards: "In the middle of the street lay the remains of a baby. It had been blown clean through the window and had burst on striking the roadway. To my intense relief, pitiful and horrible as it was, I was not nauseated, and found a torn piece of curtain in which to wrap it." Eventually she was appointed as one of the first women to become a full-time warden and received the sum of £2 5s a week.

Barbara Nixon served in two posts at opposite ends of the borough. At Post 2 "we had a variety of trades, from railway workers, post office sorters, lawyers, newspapermen, garage hands, to a few of no very definable profession". At Post 13, there was a small-time burglar and three men who had joined because the race tracks from which they had earned a dubious livelihood were now closed, and they had thought A.R.P. would be easy money.

Post 13 was a difficult job and it was "unwise" to ask what people had done before the war because, "owing to the fact that race tracks, boxing rings, and similarly chancy means of livelihood closed down at the outbreak of war, there was a large percentage of bookie's touts and even more parasitic professions, in the CD services, together with a collection of workers in light industry, intellectuals, opera singers, street traders, dog fanciers etc. In the early days the Control Rooms were crowded with chorus girls."

After the war Nixon returned to work as an actress and appeared in Tons of Money (1947), A Word in Your Eye (1947), Fortunato (1947), Lovers' Meeting (1947), Home and Beauty (1948) and BBC Sunday-Night Theatre (1950).

Barbara Nixon died in Fulbourn, Cambridgeshire, on 5th June, 1983.

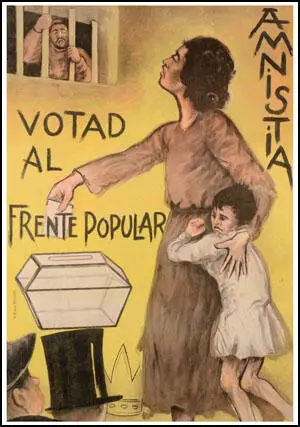

On this day in 1936 the Spanish people voted in a general election. Out of a possible 13.5 million voters, over 9,870,000 participated in the 1936 General Election. 4,654,116 people (34.3) voted for the Popular Front, whereas the National Front obtained 4,503,505 (33.2) and the centre parties got 526,615 (5.4). The Popular Front, with 263 seats out of the 473 in the Cortes formed the new government.

The Popular Front government immediately upset the conservatives by releasing all left-wing political prisoners. The government also introduced agrarian reforms that penalized the landed aristocracy. Other measures included transferring right-wing military leaders such as Francisco Franco to posts outside Spain, outlawing the Falange Española and granting Catalonia political and administrative autonomy.

As a result of these measures the wealthy took vast sums of capital out of the country. This created an economic crisis and the value of the peseta declined which damaged trade and tourism. With prices rising workers demanded higher wages. This led to a series of strikes in Spain. As a result Spanish Army officers began plotting to overthrow the Popular Front government.

On this day in 1940 Robert Smillie died. Smillie was born in Belfast on 17th March, 1857. Both parents died when Robert was very young and he was brought up by his grandmother. He received little schooling before at the age of nine, starting work as an errand boy. Two years later he found employment in a local spinning mill.

At fifteen Robert and his brother James, moved to Glasgow and worked in a brass foundry. However, before he had reached the age of seventeen he had become a miner at Larkhall. He progressed from being a pump man to a drawer of coal tubs. Finally, he became a hewer at the coal face.

Robert was keen to educate himself and for several years attended evening classes. He developed a love of reading, and especially liked the work of Robert Burns, John Ruskin and Thomas Carlyle.

Attempts were being made in Scotland to revive the miners union and 1885 Larkhall Colliery was visited by workers from Motherwell. Smillie agreed to chair a meeting of local miners and as a result a branch of the Lanarkshire Miners' Association was formed in Larkhall. Smillie was elected secretary of the branch and this involved him attending national union meetings. This brought him into contact with other union leaders including James Keir Hardie, secretary of the Ayrshire Miners' Union.

Most miners at that time were supporters of the Liberal Party. Hardie came to the conclusion that the working-class needed its own political party. Smillie shared these views and in 1888 helped James Keir Hardie when he stood as the Independent Labour candidate for the constituency of Mid-Lanark. During the election campaign Hardie and Smillie advocated socialism. These views were too advanced for the electors and Hardie finished at the bottom of the poll. However, in 1888 Smillie was elected as a member of the Larkhall School Board.

In the 1892 General Election Hardie stood as the Independent Labour candidate for the West Ham South constituency in London's industrial East End. Hardie won the election and became the country's first socialist M.P. The following year Hardie and Smillie joined together with other socialists such as Tom Mann, John Glasier, H. H. Champion, Ben Tillett, Philip Snowden, and Edward Carpenter to form the Independent Labour Party.

Smillie continued as a union leader and in 1894 he was elected president of the Scottish Miners' Federation. Two years later Smillie played an important role in the formation of the Scottish Trade Union Congress. His role was recognised when he was elected chairman at its first conference, a post he was to hold until 1899. The Scottish TUC was more radical than the English TUC with many of its leaders being members of the Independent Labour Party.

Smillie also played an active role in the Miners' Federation of Great Britain (MFGB). As a member of this organisation Smillie gathered information for the Royal Commission of Mines (1906-1911). The leadership of the MFGB supported the Liberal Party and it was mainly due to the efforts of Smillie that the union affiliated to the Labour Party in 1909. Three years later Smillie became president of the MFGB.

As president of the MFGB Smillie and before the war helped establish the Triple Industrial Alliance. This was an agreement for mutual support between the three most powerful trade unions in Britain, the miners, dockers and railwaymen.

Smillie was opposed to Britain's involvement in the First World War. He called for a negotiated peace and warned against the idea of forcing men to join the British armed forces. In 1915 Robert Smillie became president of the National Council Against Conscription (after 1917 the National Council for Civil Liberties). In June 1917 Smillie was the leading speaker at the Convention in Leeds that welcomed the Russian Revolution. He was also a supporter of the No-Conscription Fellowship.

David Lloyd George saw Smillie as a dangerous man and in an attempt to control him, offered him a post in his government. He refused and when the war finished in 1918, Smillie was one of the first to call for the Labour Party to withdraw from Lloyd George's coalition government.

Although exempted from conscription during the war, 40% of miners of military age had joined the armed forces. Those miners who stayed in Britain during the First World War enjoyed improved wages and conditions. The main reason for this was that during the war the running of the mines was taken over by the government.

In 1919 Smillie called for the nationalization and workers' control of Britain mines. David Lloyd George responded by setting up a Royal Commission under the chairmanship of Lord Sankey. The Sankey Royal Commission failed to agree about the solutions to these problems, but the majority of the members did support the idea of the mines being nationalized. Smillie was furious when Lloyd George refused to nationalize the mines and allowed them to go back into private ownership.

In 1920 the mine-owners notified their workers that miners' wages were to be reduced. The miners decided to go on strike in an effort to persuade the owners to change their minds. Under the terms of the Triple Industrial Alliance, the National Union of Railwaymen (NUR) and the Transport and General Workers Union (TGWU) declared they would come out on strike in support of the miners. However, at the last moment, the leaders of the NUR and TGWU changed their minds, and although the miners went ahead with their strike they eventually had to give in and accept lower wages. Smillie was devastated by these events and in March 1921 resigned as president of the Miners' Federation of Great Britain.

Robert Smillie had tried several times to enter the House of Commons. He was defeated at by-elections in 1895 (Glasgow) and 1901 (N.E. Lanarkshire) and at General Elections held in 1906 (Paisley) and 1910 (Glasgow). Smillie was finally elected MP for Morpeth in the 1923 General Election. Smillie declined a post in the 1924 Labour Government headed by Ramsay MacDonald.

As a result of poor health, Smillie was forced to resign his Morpeth seat in 1929. His grandson, Bob Smillie, was killed while fighting in the Spanish Civil War.

On this day in 1959 Fidel Castro becomes Premier of Cuba. In its first hundred days in office Castro's government passed several new laws. Rents were cut by up to 50 per cent for low wage earners; property owned by Batista and his ministers was confiscated; the telephone company was nationalized and the rates were reduced by 50 per cent; land was redistributed amongst the peasants (including the land owned by the Castro family); separate facilities for blacks and whites (swimming pools, beaches, hotels, cemeteries etc.) were abolished.

Castro had strong views on morality. He considered that alcohol, drugs, gambling, homosexuality and prostitution were major evils. He saw the casinos and night-clubs as sources of temptation and corruption and he passed laws closing them down. Members of the Mafia, who had been heavily involved in running these places, were forced to leave the country.

Castro believed strongly in education. Before the revolution 23.6 per cent of the Cuban population were illiterate. In rural areas over half the population could not read or write and 61 per cent of the children did not go to school. Castro asked young students in the cities to travel to the countryside and teach the people to read and write. Cuba adopted the slogan: "If you don't know, learn. If you know, teach." Eventually free education was made available to all citizens and illiteracy in Cuba became a thing of the past.

The new Cuban government also set about the problem of health care. Before the revolution Cuba had 6,000 doctors. Of these, 64 per cent worked in Havana where most of the rich people lived. When Castro ordered that doctors had to be redistributed throughout the country, over half decided to leave Cuba. To replace them Cuba built three new training schools for doctors.

The death of young children from disease was a major problem in Cuba. Infant mortality was 60 per 1,000 live births in 1959. To help deal with this Cuba introduced a free health-service and started a massive inoculation program. By 1980 infant mortality had fallen to 15 per 1,000. This figure is now the best in the developing world and is in fact better than many areas of the United States.

It has been estimated that in his seven-year reign, Batista's regime had murdered over 20,000 Cubans. Those involved in the murders had not expected to lose power and had kept records, including photographs of the people they had tortured and murdered. Castro established public tribunals to try the people responsible and an estimated 600 people were executed. Although this pleased the relatives of the people murdered by Batista's government, these executions shocked world opinion.

Some of Castro's new laws also upset the United States. Much of the land given to the peasants was owned by United States corporations. So also was the telephone company that was nationalized. The United States government responded by telling Castro they would no longer be willing to supply the technology and technicians needed to run Cuba's economy. When this failed to change Castro's policies they reduced their orders for Cuban sugar.

Fidel Castro refused to be intimidated by the United States and adopted even more aggressive policies towards them. In the summer of 1960 Castro nationalized United States property worth $850 million. He also negotiated a deal where by the Soviet Union and other communist countries in Eastern Europe agreed to purchase the sugar that the United States had refused to take. The Soviet Union also agreed to supply the weapons, technicians and machinery denied to Cuba by the United States.

President Dwight Eisenhower was in a difficult situation. The more he attempted to punish Castro the closer he became to the Soviet Union. His main fear was that Cuba could eventually become a Soviet military base. To change course and attempt to win Castro's friendship with favourable trade deals was likely to be interpreted as a humiliating defeat for the United States. Instead Eisenhower announced that he would not buy any more sugar from Cuba.

In March I960, Eisenhower approved a CIA plan to overthrow Castro. The plan involved a budget of $13 million to train "a paramilitary force outside Cuba for guerrilla action." The strategy was organised by Richard Bissell and Richard Helms. An estimated 400 CIA officers were employed full-time to carry out what became known as Operation Mongoose. Edward Lansdale became project leader whereas William Harvey became head of what became known as Task Force W. The JM WAVE station served as operational headquarters for Operation Mongoose.

Sidney Gottlieb of the CIA Technical Services Division was asked to come up with proposals that would undermine Castro's popularity with the Cuban people. Plans included a scheme to spray a television studio in which he was about to appear with an hallucinogenic drug and contaminating his shoes with thallium which they believed would cause the hair in his beard to fall out.

These schemes were rejected and instead Bissell decided to arrange the assassination of Castro. In September 1960, Richard Bissell and Allen W. Dulles, the director of the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA), initiated talks with two leading figures of the Mafia, Johnny Roselli and Sam Giancana. Later, other crime bosses such as Carlos Marcello, Santos Trafficante and Meyer Lansky became involved in this plot against Castro.

Robert Maheu, a veteran of CIA counter-espionage activities, was instructed to offer the Mafia $150,000 to kill Fidel Castro. The advantage of employing the Mafia for this work is that it provided CIA with a credible cover story. The Mafia were known to be angry with Castro for closing down their profitable brothels and casinos in Cuba. If the assassins were killed or captured the media would accept that the Mafia were working on their own.

The Federal Bureau of Investigation had to be brought into this plan as part of the deal involved protection against investigations against the Mafia in the United States. Castro was later to complain that there were twenty ClA-sponsered attempts on his life. Eventually Johnny Roselli and his friends became convinced that the Cuban revolution could not be reversed by simply removing its leader. However, they continued to play along with this CIA plot in order to prevent them being prosecuted for criminal offences committed in the United States.

In 1961 Eisenhower retired and the problem of dealing with Castro was passed on to the new president, John F. Kennedy. The new president continued with Eisenhower's policy of trying to assassinate Castro. This became known as Operation Freedom and was placed under the control of Robert Kennedy.

In the three years that followed the revolution, 250,000 Cubans out of a population of six million left the country. Most of these were from the upper and middle-classes who were financially worse off as a result of Castro's policies.

Of those who stayed, 90 per cent of the population, according to public opinion polls, supported Castro. However, Castro did not keep his promise of holding free elections. Castro claimed the national unity that had been created would be destroyed by the competing political parties in an election.

Fidel Castro was also becoming less tolerant towards people who disagreed with him. Ministers who questioned the wisdom of his policies were sacked and replaced by people who had proved their loyalty to him. These people were often young, inexperienced politicians who had fought with him in the Sierra Maestra.

Politicians who publicly disagreed with him faced the possibility of being arrested. Writers who expressed dissenting views and people he considered deviants such as homosexuals were also imprisoned.

When John F. Kennedy replaced Dwight Eisenhower as president of the United States he was told about the CIA plan to invade Cuba. Kennedy had doubts about the venture but he was afraid he would be seen as soft on communism if he refused permission for it to go ahead. Kennedy's advisers convinced him that Castro was an unpopular leader and that once the invasion started the Cuban people would support the ClA-trained forces.

On April 14, 1961, B-26 planes began bombing Cuba's airfields. After the raids Cuba was left with only eight planes and seven pilots. Two days later five merchant ships carrying 1,400 Cuban exiles arrived at the Bay of Pigs. The attack was a total failure. Two of the ships were sunk, including the ship that was carrying most of the supplies. Two of the planes that were attempting to give air-cover were also shot down. Within seventy-two hours all the invading troops had been killed, wounded or had surrendered.

At the beginning of September 1962, U-2 spy planes discovered that the Soviet Union was building surface-to-air missile (SAM) launch sites. There was also an increase in the number of Soviet ships arriving in Cuba which the United States government feared were carrying new supplies of weapons. President John Kennedy complained to the Soviet Union about these developments and warned them that the United States would not accept offensive weapons (SAMs were considered to be defensive) in Cuba.

As the Cubans now had SAM installations they were in a position to shoot down U-2 spy-planes. Kennedy was in a difficult situation. Elections were to take place for the United States Congress in two month's time. The public opinion polls showed that his own ratings had fallen to their lowest point since he became president.

In his first two years of office a combination of Republicans and conservative southern Democrats in Congress had blocked much of Kennedy's proposed legislation. The polls suggested that after the elections he would have even less support in Congress. Kennedy feared that any trouble over Cuba would lose the Democratic Party even more votes, as it would remind voters of the Bay of Pigs disaster where the CIA had tried to oust Castro from power. One poll showed that over 62 per cent of the population were unhappy with his policies on Cuba. Understandably, the Republicans attempted to make Cuba the main issue in the campaign.

This was probably in Kennedy's mind when he decided to restrict the flights of the U-2 planes over Cuba . Pilots were also told to avoid flying the whole length of the island. Kennedy hoped this would ensure that a U-2 plane would not be shot down, and would prevent Cuba becoming a major issue during the election campaign.

On September 27, a CIA agent in Cuba overheard Castro's personal pilot tell another man in a bar that Cuba now had nuclear weapons. U-2 spy-plane photographs also showed that unusual activity was taking place at San Cristobal. However, it was not until October 15 that photographs were taken that revealed that the Soviet Union was placing long range missiles in Cuba.

President Kennedy's first reaction to the information about the missiles in Cuba was to call a meeting to discuss what should be done. Fourteen men attended the meeting and included military leaders, experts on Latin America, representatives of the CIA, cabinet ministers and personal friends whose advice Kennedy valued. This group became known as the Executive Committee of the National Security Council. Over the next few days they were to meet several times.

At the first meeting of the Executive Committee of the National Security Council, the CIA and other military advisers explained the situation. After hearing what they had to say, the general feeling of the meeting was for an air-attack on the missile sites. Remembering the poor advice the CIA had provided before the Bay of Pigs invasion, John F. Kennedy decided to wait and instead called for another meeting to take place that evening. By this time several of the men were having doubts about the wisdom of a bombing raid, fearing that it would lead to a nuclear war with the Soviet Union. The committee was now so divided that a firm decision could not be made.

The Executive Committee of the National Security Council argued amongst themselves for the next two days. The CIA and the military were still in favour of a bombing raid and/or an invasion. However, the majority of the committee gradually began to favour a naval blockade of Cuba.

Kennedy accepted their decision and instructed Theodore Sorensen, a member of the committee, to write a speech in which Kennedy would explain to the world why it was necessary to impose a naval blockade of Cuba.

As well as imposing a naval blockade, Kennedy also told the air-force to prepare for attacks on Cuba and the Soviet Union. The army positioned 125,000 men in Florida and was told to wait for orders to invade Cuba. If the Soviet ships carrying weapons for Cuba did not turn back or refused to be searched, a war was likely to begin. Kennedy also promised his military advisers that if one of the U-2 spy planes were fired upon he would give orders for an attack on the Cuban SAM missile sites.