On this day on 15th August

On this day in 1803 John Scolfield gives evidence against William Blake in his treason trial. "Blake said the French knew our strength very well, and if the French set foot on English ground that every Englishman would be put to his choice whether to have his throat cut or to join the French and that he was a strong man and would certainly begin to cut throats and the strongest man must conquer - that he damned the King of England - his country and his subjects - that his soldiers were all bound for slaves and all the poor people in general."

On this day in 1845 the artist Walter Crane is born. Walter Crane was born in Liverpool. Walter's father, Thomas Crane, was a moderately successful portrait painter. When he was a child the family lived in Torquay.

Crane took a keen interest in art as a child and according to Rodney K. Engen "as a boy, Crane worked in his father's studio sketching the hands and faces of his father's portrait commissions".

In his autobiography Crane pointed out: "My early experiments with the pencil - and I never remember being without one of some kind - procured for me a certain local repute among our neighbours and acquaintances... I picked up in my father's studio and under his eye a variety of artistic knowledge in an unsystematic way. I was always drawing, and any reading, or looking at prints or pictures, led back to drawing again."

In 1851 the family moved to London with the hope that this would provide Crane with more clients. Unfortunately, just as business was improving, Thomas Crane died. Soon after his father's death Walter Crane obtained an apprenticeship with William James Linton who ran an engraving shop.

Linton was an active member of the Chartist movement and been co-editor of its newspaper, Cause of the People, with George Jacob Holyoake. Linton was one of the leaders of Moral Force movement. Edward Royle has pointed out that Linton's "belief in equality - and women were not excluded - and optimism concerning the improvability and intelligence of the human race, together with the conviction that the whole nation required the free participation of all citizens, underpinned the case for moral force Chartism."

Walter Crane later recalled: "W. J. Linton was in appearance small of stature, but a very remarkable-looking man. His fair hair, rather fine and thin, fell in actual locks to his shoulders, and he wore a long flowing beard and moustache, then beginning to be tinged with grey... He had abundance of nervous energy and moved with a quick, rapid step, coming into the office with a sort of breezy rush, bringing with him always a stimulating sense of vitality. He spoke rapidly in a light-toned voice, frequently punctuated with a curious dry, obstructed sort of laugh. Altogether a kindly, generous, impulsive, and enthusiastic nature, a true socialist at heart, with an ardent love of liberty and with much of the revolutionary feeling of 1848 about him."

Linton's stories of the struggle for parliamentary reform, had an important influence on Crane's early political development. As it was with another of Linton's students, William Luson Thomas, the founder of the weekly radical newspaper, The Graphic.

Linton was impressed by the quality of Crane's work and helped to find him commissions. This included providing the illustrations for a book being planned by John R. Wise. Crane went to live with Wise for six weeks while he was working on the pictures for The New Forest: its History and its Scenery (1862). Wise had radical political and religious opinions and introduced Crane to the work of John Stuart Mill and Percy Bysshe Shelley.

William James Linton introduced Crane to John Ruskin: "I was at last actually in the presence of the great man - and I am sure he had no more enthusiastic admirer and devoted follower at that time than the youth of fifteen in Linton's office. In appearance Mr. Ruskin at that time was still like that early remarkable full-length portrait by Millais, though perhaps nearer to Herkomer's fine water-colour head of him, before he grew a beard. I recall his tall thin figure with a slight stoop, and his quiet, rather abstracted manner. He looked like an old-fashioned type of country gentleman with literary tastes, and wore the high velvet-collared coat one sees in his early portraits".

Jeff A. Menges has pointed out: "Linton, recognizing Crane's imaginative passion, provided the youth with creative outlets. The apprenticeship served Crane's future in many ways - he had grained an insight into printing processes, which gave him a technical advantage when considering methods to improve upon the reproduction of his work with Linton. And it gave Crane on understanding of craftsmanship, which would become increasingly important to him later on in life - when Crane felt it had begun to dwindle from the materials consumed and produced in Victorian England."

Walter Crane was very impressed with cartoonists such as John Leech and John Tenniel who worked for Punch Magazine. At the time "John Leech and Tenniel were then the chief supporters of Punch and often, during the dinner-hour, I used to wander through the Temple and out into Fleet Street, and study the cartoons displayed in the window of the old Punch office at No. 185." He also liked the work of the illustrator Charles Keene.

Crane was asked to contribute illustrations to a series of books for very young children, nursery rhymes and fairy tales, to be printed by Edmund Evans, the leading woodblock colour printer in London, and published by Routledge. Over the next ten years Crane illustrated thirty-seven of these Toy Books, as they were known. These early drawings were influenced by his study of some Japenese prints he had discovered.

His biographer, Alan Crawford, argues: "After the first nine his work began to emulate Japanese prints, with decorative compositions in flat, or very deep, perspective; and he began to furnish his pictures with the fashions and domestic bric-à-brac of the aesthetic movement... Nursery rhymes and fairy tales are full of pigs going to market and dishes eloping with spoons. Crane had a taste for such fantasy, especially the anthropomorphic animals - was his name not a bird? His peculiar sensibility wedged animal lunacy up against high fashion."

In 1865 Walter Crane saw Work, a painting by Ford Madox Brown, at an art gallery in Piccadilly. The picture, shows the historian, Thomas Carlyle, and the leader of the Christian Socialist movement, F. D. Maurice, observing a group of men working. The painting marked an important development in British art because for the first time an artist had decided that a working man was a subject worth painting. Although Brown's painting did not immediately influence Crane's work, it had a profound impact on his long-term career.

In the 1860s Crane began to take an active interest in politics. He was a supporter of the Liberal Party and some of their more radical politicians such as John Stuart Mill, John Bright, Henry Fawcett and William Gladstone and campaigned for the 1867 Reform Act. He especially was taken by Mill who represented Westminster in the House of Commons. "The same sort of men were returned to Parliament, with a few notable exceptions, such as that of John Stuart Mill, who sat in the new Parliament as member for Westminster. I recall seeing and hearing him at one of the many big political meetings at St. James's Hall during the period of the Reform agitation. Gentle - mannered, small and spare of figure, but of a very marked intellectual aspect, and great earnestness, he spoke in what truly might be described as a still small voice. Philosopher and recluse, it was extraordinary the enthusiasm he evoked, standing, too, as he did for all sorts of advanced and unpopular opinions."

Walter Crane married Mary Frances Andrews on 6th September 1871. They spent the next eighteen months in Italy, where he painted portraits, landscapes as well as continuing with his book illustrations. He had paintings accepted by the Royal Academy and had several exhibitions in London art galleries. According to his biographer, Alan Crawford, "Crane produced... allegorical paintings.... almost all his life, giving them such titles as The Bridge of Life and The Roll of Fate, and he valued them above his other work. It was his ambition to show them at the Royal Academy, but he showed there only once after 1862. Instead they appeared each year at the Dudley and the Grosvenor and other London galleries, never to any acclaim. That was hard to bear, and the success of his children's books put salt in the wound. The public acclaimed him as ‘the academician of the nursery', but he wanted to be known as a distinguished allegorical painter.

Crane became close friends with William Morris. The two men both deplored the effects of modern manufacturing and the commercial system of craftsmanship and design. Deeply influenced by Morris's pamphlet Art & Socialism, Crane became involved in both the Art Workers' Guild and the Arts and Crafts Society. Like Morris, Crane created designs for wallpapers, printed fabrics, tiles and ceramics.

Morris talked to him a lot about history. He argued that John Ball and the Peasants' Revolt were early socialists. His intense earnestness and profound conviction set one thinking, however, and to a mind already more or less prepared by the economic writings of John Ruskin, and possessed of Radical sympathies in politics of long standing, it was not difficult to advance farther, even though such advance involved some divergence from the main road of contemporary thought."

In January 1884, Crane and Morris joined the Social Democratic Federation (SDF). Its leader, H. M. Hyndman, had been converted to socialism by reading the work of Karl Marx. Other significant members included, Tom Mann, John Burns, Eleanor Marx, William Morris, George Lansbury, Edward Aveling, H. H. Champion, Theodore Rothstein, Helen Taylor, John Scurr, Guy Aldred, Dora Montefiore, Frank Harris, Clara Codd, John Spargo and Ben Tillett.

Crane contributed illustrations for the party journal Justice that was edited by Henry Hyde Champion. As he later explained that he agreed to work for free as "all the work on the journal was gratuitous, from the writers of the articles to the compositors and printers." In one of his most popular drawings: "Capitalism was represented as a vampire fastening on a slumbering workman, and an emblematic figure of Socialism endeavours to arouse him to a sense of his danger by the blast of a clarion."

It has been claimed that Crane "placed his talent at the disposal of the movement" and produced "membership cards, logos, cartoons, invitation cards, posters and illustrations." John Gorman argues that it was "Walter Crane's cartoons, his black and white illustrations and engravings... that shaped the imagery of socialism on trade union banners for thirty years".

Crane, like Morris, found the SDF's leader, Hyndman, difficult. Crane shared Hyndman's Marxist beliefs, but objected to his nationalism and the dictatorial methods he used to run the party. Despite their poor relationship, Hyndman respected Crane as an artist: "Nobody, not even William Morris, did more to make Art a direct helpmate to the Socialist propaganda. Nobody has had a greater influence on the minds of doubters who feared that Socialism must be remote from and even destructive of the sense of beauty."

Crane became associating with other radicals living in London. He especially liked I met here Peter Kropotkin, the Russian anarchist. Crane wrote in his autobiography, An Artist's Reminiscences (1907): "Kropotkin... who had suffered so much for his opinions, and who has won universal respect and sympathy in this country, charming all who have had the pleasure of his acquaintance by his genial manners, his disinterested enthusiasm for the cause of humanity, and his peaceful but earnest propaganda in anarchist-communism, as well as his valuable sociological writings".

At a meeting of the Social Democratic Federation executive on 28th December, 1884, there was a heated about Hyndman's leadership. Some members, including Walter Crane, William Morris, Eleanor Marx, Ernest Belfort Bax and Edward Aveling decided to leave the SDF and formed a new organisation called the Socialist League. The group also produced its own journal, Commonweal. However, Morris was disappointed by the slow growth of the organisation. After six months the Socialist League only had eight branches and 230 members. Morris wrote to a friend: "I am in low spirits about the prospects of our party, if I can dignify a little knot of men by such a word. You see we are such a few, and hard as we work we don't seem to pick up people."

Although a Marxist, Crane hoped that socialism would be achieved through education rather than revolution. This is reflected in his decision to join the socialist debating group, the Fabian Society in October 1885. Other members included George Bernard Shaw, H. G. Wells, Sidney Webb, Beatrice Webb, Hubert Bland, Edward Pease, Havelock Ellis, Annie Besant, Graham Wallas and Frank Podmore.

The children's author, Edith Nesbit, wrote to her friend, Ada Breakell about the group: "I should like to try and tell you a little about the Fabian Society - it's aim is to improve the social system - or rather to spread its news as to the possible improvements of the social system. There are about thirty members - some of whom are working men. We meet once a fortnight - and then someone reads a paper and we all talk about it. We are now going to issue a pamphlet."

Crane agreed to give a lecture for the Fabian Society on socialism entitled Art and Commercialism. He was not a good lecturer and afterwards George Bernard Shaw remarked that Crane was only "bearable when he took up the chalk and showed what he meant on the blackboard". After this Crane tended to concentrate on doing art work for the society: "The Fabian Society certainly has done very useful educational work by its economic lectures and tracts. The Society has addressed itself more to the middle classes, and as regards Socialism has advocated a waiting or Fabian policy, relying rather on the effects of a gradual permeation of society by new ideas than emphatic protest and revolt."

In 1885 exhibited his painting Angel of Freedom at the Grosvenor Gallery. It had been inspired by the poem, The Eve of Revolution, that had been written by Algernon Charles Swinburne. It has been pointed out by John Gorman, the author of Images of Labour (1985), that "Crane's Angel of Freedom... became a symbol of working class emancipation that was adapted in a hundred ways, copied and imitated throughout the labour movement and still survives today... His angel was to become a ready symbol for labour, heralding the future sunshine of the co-operative commonwealth."

On 13th November, 1887 Walter Crane was involved with William Morris, H. H. Hyndman, Annie Besant, and John Burns in what became known as Bloody Sunday, when three people were killed and 200 injured during a public meeting in Trafalgar Square. Crane later recalled: "I never saw anything more like real warfare in my life - only the attack was all on one side. The police, in spite of their numbers, apparently thought they could not cope with the crowd. They had certainly exasperated them, and could not disperse them, as after every charge - and some of these drove the people right against the shutters in the shops in the Strand - they returned again."

The following week, a friend, Alfred Linnell, was fatally injured during another protest demonstration and this event resulted in Morris writing, Death Song. Crane provided the cover drawing for this work. Crane, as a result of a suggestion made by his friend and fellow socialist, George F. Watts, provided twelve designs that illustrated heroic deeds carried out by working-class people. This included Alice Ayres, who died while rescuing three children from a fire, and two Paisley railway workers who were killed during an attempt to help others in trouble. This work was first shown at the Arts and Crafts Exhibition in 1890.

Walter Crane became a close friend of Oscar Wilde, who also held socialist beliefs. Wilde, who was editor of Woman's World, commissioned him to provide illustrations for the magazine. In 1888 Crane also contributed three full-page illustrations for Wilde's highly successful book, The Happy Prince and Other Tales

In 1892 Walter Crane published his influential book, The Claims of Decorative Art, where he argued that art could not flourish in a world where wealth was so unfairly distributed. Crane claimed that only under "Socialism could Use and Beauty be united". The following year he was appointed director of design at Manchester School of Art. In 1898 he became principal of the Royal College of Art. His collected lectures were published in two books, The Bases of Design (1898) and Line and Form (1900).

Crane also attacked the impact of the industrial revolution on society: "Steam machinery, intended for the service of man and for the saving of human labour had under our economic system enslaved humanity instead, and become an engine for the production of profits, an express train in the race for wealth, only checked by the brake of what is called over-production."

The Crane family moved to 13 Holland Street, off Kensington Church Street. "They lived a life of self-conscious bohemianism. The house was full of pewter and china, carved figures, Indian idols, a live alligator, model ships, a marmoset that slept in the fireplace, Crane's unsold paintings, all higgledy-piggledy and gathering dust. Amid all this Crane played the part of the artist, a small, dapper man with carefully curled moustaches and a little beard, a flowing yellow silk tie, and a velvet coat. Colleagues were apt to laugh at him, and they mostly thought his earliest works, the Toy Books, were the best. But he was a lovable figure, and they indulged his staginess. Both he and Mary Crane loved dressing up and they threw enormous parties."

Walter Crane remained a committed socialist and a collection of Crane's political cartoons, Cartoons for the Cause, were published as a souvenir of the International and Trade Union Congress that met in London in 1896. He also supported the Labour Party when it was formed in 1900 and each May Day he would produce a poster for the organisation. Their purpose was, as Crane explained: "Directed to the embodiment of the principles of socialism and unmistakably inscribed with legends expressing the political aims and social aspirations of the party".

Crane's posters could be found "brightening the dreary walls of dingy meeting rooms" and in the homes of socialists: "Capitalism was a serpent, a wolf or a dragon; the workers were men of Morris's England, labourers and craftsmen, strong and determined, ever ready to slay the monster of evil, the capitalist system. Socialism was a sunny future, the millennium, almost but not quite within the eager grasp of a Phrygian-capped proletariat... The image of socialism bearing the torch, the banner of the keys of freedom was invariably a woman. Grecian robed, wearing the cap of liberty, sometimes graced with the wings of an angel, a heroine that was neither Britannia nor Joan of Arc yet encapsulated motherhood, beauty and courage... The influence of Crane's art upon the iconography of the working class movement was immense and nowhere was it in greater evidence than upon the giant silken banners of the trades unions that had their golden age during the last decade of the nineteenth century".

Crane, like many socialists, believed that wars were often begun by capitalists for reasons of commerce than for idealism. In 1900 Crane joined with Ramsay MacDonald and Emmeline Pankhurst in resigning from the Fabian Society over its decision not to condemn the Boer War. Crane was a strong critic of the British Empire and after spending time with Annie Besant in India, wrote India Impressions (1907) that included severe criticisms of the way that the country was being ruled by the British.

Walter Crane published his autobiography, An Artist's Reminiscences in 1907. In the book he attempted to explain why he had spent so much of his life fighting for socialism: "Such experiences convinced me that freedom in any country is measured by the impunity with which unpopular opinions can be uttered - especially those advocating drastic political or social changes - or by the length of the tether of toleration, and that certain public rights may be won, but that they require constant vigilance to defend and maintain. It was a stormy period, and the bourgeois were in a panic, and the wildest ideas of Socialism were about. We were mis-represented and abused in every direction, and confused with the advocates of the use of dynamite."

Crane's work during this period was to have a lasting impression on the art of the labour movement in Britain. Between the 1880s and the First World War, the socialist iconography developed by Crane can be seen on posters, pamphlets, membership cards and trade union banners. Crane's work was also widely circulated in Europe, and in Italy and Germany his reputation as an artist was greater than it was in England.

On 18th December 1914 Mary Crane was found dead on the railway line near Kingsnorth in Kent. The couple had been married for forty-four years and Crane was devastated by her death. Walter Crane died three months later in Horsham Hospital, on 14th March, 1915.

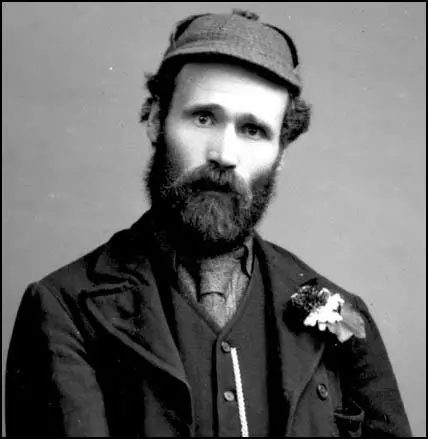

On this day in 1856 Keir Hardie, the illegitimate son of Mary Keir, a servant from Legbrannock, near Holytown, Lanarkshire, Scotland, was born on 15th August, 1856. It is possible that his father was William Aitkin, a miner. Three years later Mary married David Hardie, a ship's carpenter from Falkirk. After this date he was known as James Keir Hardie.

The family moved to the Partick district of Glasgow. At the age of eight Hardie became a baker's delivery boy. He had to work for twelve and a half hours a day and for his labours received 3s. 6d. a week. With his step-father unemployed, and his mother pregnant, Hardie was the only wage-earner in the family.

In December 1866, his mother and younger brother were seriously ill and he had to nurse them through the night. As a result he was late for work and he was shocked when he was sacked for this offence. "I was discharged, and my fortnight's wages forfeited by way of punishment. The news stupefied me, and I finally burst out crying and begged the shopwoman to intercede with the master for me. The morning was wet, and I had been drenched in getting to the shop, and must have presented a pitiable sight as I stood at the counter in my well-patched clothes. She spoke to the master through a speaking-tube... but he was obdurate, and finally she, out of the goodness of her heart, gave me a piece of bread... For a time I wandered about the streets in the rain, ashamed to go home where there was neither food nor fire, and actually discussing with myself whether the best thing was not to go and throw myself in the Clyde and be done with a life that had so little attractions."

Unable to find work in Glasgow, the family moved back to Lanarkshire, and at the age of eleven, Hardie became a coal miner, working for "twelve or fourteen hours a day". Initially he worked as a trapper. "The work of a trapper was to open and close a door which kept the air supply for the men in a given direction. It was an eerie job, all alone for ten long hours, with the underground silence only disturbed by the sighing and whistling of the air as it sought to escape through the joints of the door."

Hardie, who never attended school, was completely illiterate until his mother began to teach him to read. His friend, Philip Snowden, explained why this happened: "Keir Hardie had no schooling as a boy. He told me once what drove him to learn to write. When a youth, he went to join the Good Templers. He was unable to sign his name on the membership pledge, and he was so ashamed that he set to work to learn to write."

Although Hardie worked 12 hours a day down the mine, he still found time for his studies and by the age of seventeen had learnt to write from a man who provided evening classes to miners: "The teacher was genuinely interested in his pupils and did all he could for them with his limitations of time and equipment. There was no light provided in the school and the pupils had to bring their own candles. Learning had now a kind of fascination for the boy".

Hardie began to read newspapers and discovered how some workers were attempting to improve their wages and working conditions by forming trade unions. Hardie helped join a union at his colliery and in 1880 took part in the first ever strike of Lanarkshire miners. This led to his dismissal, and he moved to Old Cumnock.

Hardie became a member of the Temperance Society. He met and married Lillie Wilson, a fellow campaigner. As Fran Abrams has pointed out: "He (Hardie) enjoyed the company of women, and Lillie was not the first girl to catch his eye. The marriage was not always a source of joy to either party... for Hardie, politics always came first. The day after his wedding he attended a political rally and set the pattern for the rest of his married life. While he travelled the globe in pursuit of his causes, Lillie was left at home, struggling to bring up a growing family."

Keir Hardie read the works of Thomas Carlyle, John Ruskin, Ralph Waldo Emerson and Charles Dickens in order to develop his writing style. He "acquired the skills of Pitman's shorthand by scratching out the characters on a blackened slate with the wire used by miners to adjust the wicks of their lamps, in the dark depths of a Lanarkshire pit". He also began having articles published in a local newspaper.

In May 1879, Scottish mine owners combined to force a reduction of wages. Hardie was appointed Corresponding Secretary of the miners, a post which gave him opportunity to get in touch with other representatives of the mine workers throughout southern Scotland. In the summer of 1880, the Hamilton miners defied their union and went on strike against a wage reduction. The strike was crushed, but Hardie was appointed secretary for the recently formed Ayrshire Miners' Union.

A friend at this time claimed that although he never drank alcohol he was good company: "A Puritan he was in all matters of absolute right or wrong, and could not be made to budge from what seemed to him to be the straight path. But with that limitation he was one of the most companionable of men. He could sing a good song, and dance and be merry with great abandon."

James Mavor met Keir Hardie for the first time in 1879: "When I first met him he was an alert, good-looking young man - reddish hair, ruddy complexion, honest but ecstatic eyes, average stature, very fastidious about his dress... Hardie looked like an artist, and indeed in general his point of view was that of an artist... Although his early education had been somewhat neglected, Hardie had the talent for letters which seems to be indigenous in Ayrshire. He was a creature of impulse. His impulses were always genuine, no matter how mistaken might be the judgments associated with them... He never fell into the habits of his fellows, but identified himself rather with the intellectual and artistic proletariat than with any faction of the middle class. This was no pose, but was the simple outcome of his nature. He was the only really cultivated man in the ranks of any of the Labour parties."

In 1882 Keir Hardie met Henry George, the American author of Our Land and Land Policy (1870) and Progress and Poverty (1877). His friend Philip Snowden later argued: "Keir Hardie told me that it was Progress and Poverty which gave him his first ideas of socialism... No book ever written on the social problem made so many converts. Economic facts and theories have never been presented in such an attractive way. Although Henry George was not a socialist, his book led many of his readers to socialism."

Keir Hardie admitted that his conversion to socialism was a "protracted process" and had "no real base in economics". He described socialism as "more an affair of the heart than of the intellect" and saw it as a political system that would protect and support weaker members of the community. He agreed with Karl Marx that capitalists were a "corrupt class" and "endorsed his vision of the historical struggle of the workers" but rejected his ideas on the need for revolution to change society.

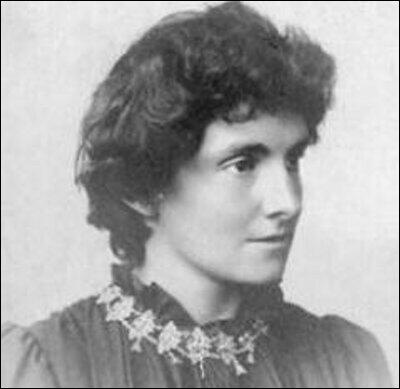

On this day in 1858 Edith Nesbit, the daughter of John Collis Nesbit, a schoolmaster, was born on 19th August, 1858. Nesbit ran successful schools in Bradford, Manchester and London but died when Edith was only six years old. Despite money problems, Edith's mother managed to educate her daughter in boarding schools in Brighton and France. She later recalled: "When I was a little child I used to pray fervently, tearfully, that when I should be grown up I might never forget what I thought and felt and suffered then".

At the age of nineteen, Edith Nesbit met Hubert Bland, a young writer with radical political opinions. In 1879 discovered she was pregnant and the baby was born two months after they were married on 22nd April, 1880. According to her biographer, Julia Briggs: "Bland continued to spend half of each week with his widowed mother and her paid companion, Maggie Doran, who also had a son by him, though Edith did not realize this until later that summer when Bland fell ill with smallpox. With characteristic optimism, she forgave him, befriended Maggie, and set about supporting the household by writing sentimental poems and short stories, and by hand-painting greetings cards."

Edith and Hubert were both socialists and on 24th October 1883 they decided with their Quaker friend Edward Pease, to form debating group. They were also joined by Havelock Ellis and Frank Podmore and in January 1884 they decided to call themselves the Fabian Society. Bland chaired the first meeting and was elected treasurer. Nesbit and her husband became joint editors of the society's journal, Today. Soon afterwards other socialists in London began attending meetings. This included Eleanor Marx, Annie Besant, Olive Schreiner, Clementina Black, Sidney Webb and Beatrice Webb.

In April 1884 Edith wrote to her friend, Ada Breakell: "I should like to try and tell you a little about the Fabian Society - it's aim is to improve the social system - or rather to spread its news as to the possible improvements of the social system. There are about thirty members - some of whom are working men. We meet once a fortnight - and then someone reads a paper and we all talk about it. We are now going to issue a pamphlet. I am on the Pamphlet Committee. Now can you fancy me on a committee? I really surprise myself sometimes."

George Bernard Shaw joined the Fabian Society in August 1884. Edith wrote: "The Fabian Society is getting rather large now and includes some very nice people, of whom Mr. Stapelton is the nicest and a certain George Bernard Shaw the most interesting. G.B.S. has a fund of dry Irish humour that is simply irresistible. He is a clever writer and speaker - is the grossest flatterer I ever met, is horribly untrustworthy as he repeats everything he hears, and does not always stick to the truth, and is very plain like a long corpse with dead white face - sandy sleek hair, and a loathsome small straggly beard, and yet is one of the most fascinating men I ever met."

In 1885 Edith Nesbit and Hubert Bland also joined the Social Democratic Federation. Other members included Tom Mann, John Burns, Eleanor Marx, William Morris, George Lansbury, Edward Aveling, H. H. Champion, John Scurr, Guy Aldred, Dora Montefiore, Frank Harris, Clara Codd, John Spargo and Ben Tillet. However, they did not stay long as they found the views of its leader, H. H. Hyndman, too revolutionary.

Edith wrote two novels, The Prophet's Mantle (1885) and Something Wrong (1886), about the early days of the socialist movement, under the pen-name Fabian Bland. In 1885 Edith had a second child and named him Fabian. In February 1886, Edith gave birth to a stillborn child, and her friend Alice Hoatson, the assistant secretary of the Fabian Society, came to look after her. Alice stayed as their housekeeper in a ménage à trois, and the following year, Alice gave birth to Hubert's baby, Rosamund. Edith accepted the situation and brought up Rosamund as her own child.

Hubert's promiscious behaviour encouraged her to have relationships with other men. The poet Richard Le Gallienne was one of those who found her very attractive and was charmed by her "tall lithe boyish-girl figure, admirably set off by her plain Socialist gown, with her short hair, and her large vivid eyes". Another admirer commented on "the sheer magnificence of her appearance... with a long full throat, and dark luxuriant hair, smoothly parted." George Bernard Shaw found her very attractive and met her two or three times a week at local cafes. However, in May 1887 he reported that "she went away after an unpleasant scene caused by my telling her I wished her to go as I was afraid that a visit to me (at his home) would compromise her."

Another close friend was Oswald Barron, a young journalist. Claire Tomalin points out: "He was one of a band of her courtiers, recent Oxford graduates who joined the Fabian Society and were fascinated by the Blands, and notably by Edith. For she was beautiful in her own style - lots of hair and a strong face, trailing Liberty dresses, ropes of beads and dozens of bangles on her arm, incessant cigarettes in a long holder - and the parties she and Hubert gave were famous, with huge meals, wine and games played all over the house."

Edith Nesbit was a regular lecturer and writer on socialism throughout the 1880s. However she gave less time to these activities after she published The Story of the Treasure-Seekers (1899). Julia Briggs has pointed out: "With the creation of Oswald Bastable, she knew that she had discovered a highly original way of writing about and for children, and from this point in her career she never looked back. She now invented the children's adventure story, more or less single-handed, adding to it fantasy, magic, time-travel, and a delightful vein of subversive comedy. The next ten years or so saw the publication of all her major work, and in the mean time she was also composing poems, plays, romantic novels, ghost stories, and tales of country life."

Other books by Nesbit included, The Wouldbegoods (1901), Five Children and It (1902), The Pheonix and the Carpet (1904), The New Treasurer-Seekers (1904), The Railway Children (1906) and The Enchanted Castle (1907). A collection of her political poetry, Ballads and Lyrics of Socialism, was published in 1908.

Claire Tomalin has argued: "Nesbit's books were hugely popular with children and adults, admired by writers as various as Kipling and Wells, and have remained in print ever since... Their recurring theme of lost and found fathers addresses itself to children's deep fears and hopes. Another theme, that of the wish granted that turns out to be awkward or frightening, goes similarly straight to the heart of the fantasies and semi-conscious terrors of many children."

Hubert Bland died after suffering a heart attack on 14th April 1914. In the summer of 1916 she met Thomas Terry Tucker (1856–1935), a widowed marine engineer who shared her socialistic political views. She told her sister, "I feel as though someone had come and put a fur cloak round me.". Her children disapproved of the relationship because he "spoke with a broad cockney accent and never wore a collar" but she was deeply in love and they were married on 20th February 1917 at St Peter's Roman Catholic Church in Woolwich.

Edith Nesbit continued to write children's books and had published forty-four novels before her death from lung cancer at her home in St Mary's Bay in Romney Marsh, on 4th May, 1924.

On this day in 1885 Edna Ferber, the daughter of Jacob Ferber, a Jewish storekeeper, and Julia Neumann Ferber, was born in Kalamazoo, Michigan, on 15th August, 1885. When she was a child the family moved to Appleton, Wisconsin, where she attended the local high school. Ferber briefly attended Lawrence University before becoming a journalist on the Appleton Daily Crescent and the Milwaukee Journal.

Ferber's first novel, Dawn O'Hara: The Girl Who Laughed, was published in 1911. This was followed by Buttered Side Down (1912), Roast Beef Medium The Business Adventures Of Emma McChesney (1913), Personality Plus (1914), Our Mrs. McChesney (1915), Fanny Herself (1917), Cheerful – By Request (1918), Half Portions (1919), The Girls (1921) and Gigolo (1922).

Robert E. Sherwood, Dorothy Parker and Robert Benchley all worked at Vanity Fair during the First World War. They began taking lunch together in the dining room at the Algonquin Hotel. Sherwood was six feet eight inches tall and Benchley was around six feet tall, Parker, who was five feet four inches, once commented that when she, Sherwood and Benchley walked down the street together, they looked like "a walking pipe organ." Ferber became friends with this small group and would sometimes have lunch with them in the hotel.

According to Harriet Hyman Alonso , the author of Robert E. Sherwood The Playwright in Peace and War (2007): "John Peter Toohey, a theater publicist, and Murdock Pemberton, a press agent, decided to throw a mock "welcome home from the war" celebration for the egotistical, sharp-tongued columnist Alexander Woollcott. The idea was really for theater journalists to roast Woollcott in revenge for his continual self-promotion and his refusal to boost the careers of potential rising stars on Broadway. On the designated day, the Algonquin dining room was festooned with banners. On each table was a program which misspelled Woollcott's name and poked fun at the fact that he and fellow writers Franklin Pierce Adams (F.P.A.) and Harold Ross had sat out the war in Paris as staff members of the army's weekly newspaper, the Stars and Stripes, which Bob had read in the trenches. But it is difficult to embarrass someone who thinks well of himself, and Woollcott beamed at all the attention he received. The guests enjoyed themselves so much that John Toohey suggested they meet again, and so the custom was born that a group of regulars would lunch together every day at the Algonquin Hotel."

Murdock Pemberton later recalled that he owner of the hotel, Frank Case, did what he could to encourage this gathering: "From then on we met there nearly every day, sitting in the south-west corner of the room. If more than four or six came, tables could be slid along to take care of the newcomers. we sat in that corner for a good many months... Frank Case, always astute, moved us over to a round table in the middle of the room and supplied free hors d'oeuvre.... The table grew mainly because we then had common interests. We were all of the theatre or allied trades." Case admitted that he moved them to a central spot at a round table in the Rose Room, so others could watch them enjoy each other's company.

The people who attended these lunches included Ferber, Robert E. Sherwood, Dorothy Parker, Robert Benchley, Alexander Woollcott, Heywood Broun, Harold Ross, Donald Ogden Stewart, Ruth Hale, Franklin Pierce Adams, Jane Grant, Neysa McMein, Alice Duer Miller, Charles MacArthur, Marc Connelly, George S. Kaufman, Beatrice Kaufman , Frank Crowninshield, Ben Hecht, John Peter Toohey, Lynn Fontanne, Alfred Lunt and Ina Claire. This group eventually became known as the Algonquin Round Table.

Edna Ferber wrote about her membership of the group in her book, A Peculiar Treasure (1939): "The contention was that this gifted group engaged in a log-rolling; that they gave one another good notices, praise-filled reviews and the like. I can't imagine how any belief so erroneous ever was born. Far from boosting one another they actually were merciless if they disapproved. I never have encountered a more hard-bitten crew. But if they liked what you had done they did say so, publicly and wholeheartedly. Their standards were high, their vocabulary fluent, fresh, astringent and very, very tough. Theirs was a tonic influence, one on the other, and all on the world of American letters. The people they could not and would not stand were the bores, hypocrites, sentimentalists, and the socially pretentious. They were ruthless towards charlatans, towards the pompous and the mentally and artistically dishonest. Casual, incisive, they had a terrible integrity about their work and a boundless ambition."

Ferber had her first major success with her novel, So Big, which was awarded the Pulitzer Prize in 1924. Later that year Ferber began writing plays another member of the Algonquin Round Table, the former journalist, George S. Kaufman. The author of George S. Kaufman: An Intimate Portrait (1972) has argued: "In many ways she was very much like Kaufman: middle-western birthplace, same German-Jewish background, same training as a newspaper reporter, same discipline toward work. In other ways she was the direct opposite of Kaufman. She was small in physical stature, and a great believer in exercise. She had great personal courage, an overwhelming desire to travel, to seek new people, new places, new ideas. She did not have Kaufman's wit, but she did have the ability to write rich, deep love scenes."

Their first play together was Minnick . It opened at the Booth Theatre on 24th September, 1924 and ran for 141 performances. Alexander Woollcott said that the play "loosed vials of vitriol out of all proportion to the gentle little play's importance." Feber replied that she found the review "just that degree of malignant poisoning that I always find so stimulating in the works of Mr. Woollcott". This led to a long-running dispute between the two former friends. Woollcott's biographer, Samuel Hopkins Adams, claims that it started as "the inevitable bickerings which are bound to occur between two highly sensitized temperaments."

This was followed by Show Boat (1926). This was turned into a popular musical by Jerome Kern and Oscar Hammerstein II, that featured Paul Robeson. She also continued to write with Kaufman. Their next play, The Royal Family, was based on the lives of Ethel Barrymore, John Barrymore and Lionel Barrymore. It took eight months to write and after being cleared by the Barrymore family lawyers it opened at the Selwyn Theatre on 28th December, 1927. Produced by Jed Harris and directed by David Burton, it was a great success and ran for 345 performances.

They were unable to recapture this success and eventually broke up the writing partnership. Ferber later admitted that she was always afraid of George S. Kaufman and they had a difficult relationship. "When he needled you, it was like a cold knife that he stuck into your ribs. And he did it so fast, so quickly, you didn't even see it go in. You only felt the pain." Kaufman told his friends that he lived in mortal fear of Ferber. He disliked her temper and her love of quarrels.

Feber's next novel, Cimarron (1929), about the Oklahoma Land Rush, was later turned into the Academy Award winning film of the same name. Ferber held left-wing political views and campaigned for Heywood Broun when he stood as a candidate for the Socialist Party of America in 1930. She was also a member of the Progressive Citizens of America (PCA). Its members included Henry A. Wallace, Rexford Tugwell, Paul Robeson, W.E.B. Du Bois, Arthur Miller, Dashiell Hammett, Hellen Keller, Thomas Mann, Aaron Copland, Claude Pepper, Eugene O'Neill, Glen H. Taylor, John Abt, Thornton Wilder, Carl Van Doren, Fredric March and Gene Kelly.

The playwright, Howard Teichmann, claims that Ferber's difficult relationship with Alexander Woollcott became worse after the events that took place on the opening night of The Dark Tower in 1933. "Woollcott, who knew how capricious opening-night audiences could be, decided not to have the usual crowd. Instead, he selected 250 of his personal friends to fill the better part of the orchestra floor at the Morosco Theatre. Two pairs of seats went to his old pal Edna Ferber. Escorted that night by the millionaire diplomat Stanton Griffis, Miss Ferber had as guests the Hollywood motion-picture star Gary Cooper and his wife. At curtain time Miss Ferber and party had not arrived at the theater, and the house lights went down on four choice but empty seats... Aleck waddled into the lobby only to find Ferber and her party standing there while Gary Cooper gave autographs to movie fans."

The actress Margalo Gillmore later recalled that after the play had finished they all met in her dressing room. "Woollcott, Ferber, Stanton Griffis, poor Beatrice Kaufman. Woollcott glared and glared and his eyes through those thick glasses he wore seemed as big as the ends of the old telephone receivers. Ice dripped everywhere." Teichmann added that Woollcott "who felt the greatest gift he could bestow was his own presence, gave his ultimatum" that he would "never go on the Griffis yacht again".

A few weeks later, Edna Ferber, still upset by Woollcott's behaviour that night, referred to Woollcott as "That New Jersey Nero who thinks his pinafore is a toga." When he heard about the comment, Woollcott responded with the comment: "I don't see why anyone should call a dog a bitch when there's Edna Ferber around." Howard Teichmann claims that "they never spoke after that".

Other books by Ferber included American Beauty (1931), They Brought Their Women (1933) and Come and Get It (1935). Nobody's in Town (1938), A Peculiar Treasure (1939), The Land Is Bright (1941), Saratoga Trunk (1941), No Room at the Inn (1941), Great Son (1945), Giant (1952), Ice Palace (1958) and A Kind of Magic (1963).

Edna Ferber never married. She once wrote: "Life can't defeat a writer who is in love with writing, for life itself is a writer's lover until death." On another occasion she remarked: "Being an old maid is like death by drowning, a really delightful sensation after you cease to struggle." It is claimed that she had always been in love with George S. Kaufman. However, they often had disagreements when they were together. In 1960 he wrote to her. "I am an old man and not well. I have had two or three strokes already and I cannot afford another argument with you to finish my life. So I simply wish to end our friendship." After waiting a sensible amount of time, she telephoned him and they agreed to see each other again. He died in 1961.

Edna Ferber died on 16th April, 1968.

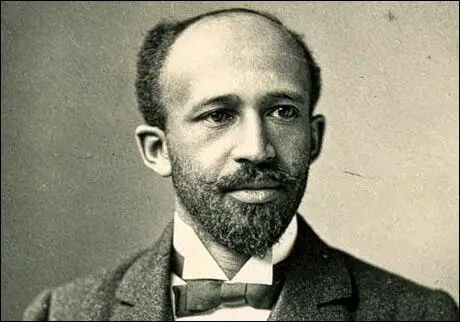

On this day in 1906 William Du Bois, makes important speech on civil rights: "We will not be satisfied to take one jot or tittle less than our full manhood rights. We claim for ourselves every single right that belongs to a free-born American, political, civil and social; and until we get these rights we will never cease to protest and assail the ears of America. The battle we wage is not for ourselves alone but for all true Americans."

Du Bois began to read the works of Henry George, Jack London and John Spargo. He eventually became converted to socialism and in 1907 he wrote that "socialism was the one great hope of the Negro in America." He also became friendly with socialists such as Mary White Ovington and William English Walling.

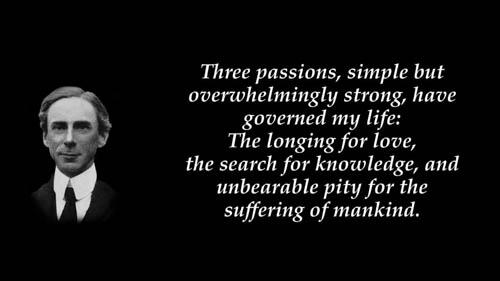

On this day in 1914 Bertrand Russell in a letter to The Nation he explains why he will not fight in the First World War.

A month ago Europe was a peaceful group of nations: if an Englishman killed a German, he was hanged. Now, if an Englishman kills a German, or if a German kills an Englishman, he is a patriot. We scan the newspapers with greedy eyes for news of slaughter, and rejoice when we read of innocent young men, blindly obedient to the world of command, mown down in thousands by the machine-gun of Liege.

Those who saw the London crowds, during the nights leading up to the Declaration of War saw a whole population, hitherto peaceable and humane, precipitated in a few days days down the steep slope to primitive barbarism, letting loose, in a moment, the instincts of hatred and blood lust against which the whole fabric of society has been raised.

The friends of progress have been betrayed by their chosen leaders, who have plunged the country suddenly into a war which must cause untold misery, and which an overwhelming majority of those who voted for the present Government believe to be as unwise as it is wicked. No man whose liberalism is genuine can hearafter support the members of the present Cabinet.

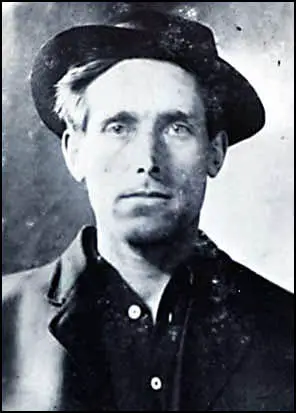

On this day in 1915 Joe Hill wrote an article in Appeal to Reason about his case before his execution.

In spite of all the hideous pictures and all the bad things and printed about me, I had only been arrested once before in my life, and that was in Sal Pedro, California. At the time of the stevedores' and dock workers' strike. I was secretary of the strike committee, and I suppose I was a little too active to suit the chief of that burg, so he arrested me and gave me thirty days in the city jail for vagrancy and there you have the full extent of my "criminal record".

The main and only fact worth considering, however, is this: I never killed Morrison and do not know a thing about it. He was, as the records plainly show, killed by some enemy for the sake of revenge, and I have not been in the city long enough to make an enemy.

Shortly before my arrest I came down from Park City; where I was working in the mines. Owing to the prominence of Mr Morrison, there had to be a "goat" and the undersigned being, as they thought, a friendless tramp, a Swede, and worst of all, an I.W.W, had no right to live anyway, and was therefore duly selected to be "the goat".

I have always worked hard for a living and paid for everything I got, and in my spare time I spend by painting pictures, writing songs and composing music.

Now, if the people of the state of Utah want to shoot me without giving me half a chance to state my side of the case, bring on your firing squads - I am ready for you. I have lived like an artist and I shall die like an artist.

On this day in 1955 Pete Seeger appears before the House of Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC). On 6th February, 1952, Harvey Matusow testified in front of the HUAC that Seeger was a member of the American Communist Party. Matusow admitted in his autobiography, False Witness (1955) that this was untrue but Seeger said this ended the career of The Weavers: "Matusow's appearance burst like a bombshell... We had started off singing in some very flossy night-clubs... Then we went lower and lower as the blacklist crowded us in. Finally, we were down to places like Daffy's Bar and Grill on the outskirts of Cleveland." Despite not being a member of the party Seeger continued to describe himself as a “communist with a small ‘c.’ ”

It was another three years before Seeger was called before the HUAC. Frank Donner, a lawyer who defended several people who were called before the HUCA, wrote in The Un-Americans (1961): "He knows that the Committee demands his physical presence in the hearing room for no reason other than to make him a target of its hostility, to have him photographed, exhibited and branded... He knows that the vandalism, ostracism, insults, crank calls and hate letters that he and his family have already suffered are but the opening stages of a continuing ordeal... he is tormented by the awareness that he is being punished without valid cause, and deprived, by manipulated prejudice, of his fundamental rights as an American."

Seeger's lawyer, Paul Ross, advised him to use the Fifth Amendment defence (the right against self-incrimination). In the year of Seeger's subpoena, the HUAC called 529 witnesses and 464 (88 per cent) remained silent. Seeger later recalled: "The expected move would have been to take the Fifth. That was the easiest thing, and the case would have been dismissed. On the other hand, everywhere I went, I would have to face 'Oh, you're one of those Fifth Amendment Communists...' I didn't want to run down my friends who did use the Fifth Amendment but I didn't choose to use it."

Pete Seeger had been struck by something that I.F. Stone had written in 1953: "Great faiths can only be preserved by men willing to live by them (HUAC's violation of the First Amendment) cannot be tested until someone dares invite prosecution for contempt." Seeger decided that he would accept Stone's challenge, and use the First Amendment defence (freedom of speech) even though he knew it would probably result in him being sent to prison. Seeger told Paul Ross : "I want to get up there and attack these guys for what they are, the worst of America". Ross warned him that each time the HUCA found him in contempt, he was liable to a year in jail.

The first day of the new HUAC hearings took place on 15th August 1955. Most of the witnesses were excused after taking the Fifth Amendment. Seeger's friend, Lee Hays, also evoked the Fifth Amendment on the second day of the hearings and he was allowed to go unheeded. Seeger was expected to follow his example but instead he answered their questions. When asked for details of his occupation, Seeger replied: "I make my living as a banjo picker - sort of damning in some people's opinion." However, when Gordon Scherer, a sponsor of the John Birch Society, asked him if he had performed at concerts organized by the American Communist Party he refused to answer.

Francis Walter, the chairman of the House of Un-American Activities Committee, told Seeger: "I direct you to answer". Seeger replied: "I am not going to answer any questions as to my association, my philosophical or religious beliefs or my political beliefs, or how I voted in any election or any of these private affairs. I think these are very improper questions for any American to be asked, especially under such compulsion as this." Seeger later recalled: "I realized that I was fitting into a necessary role... This particular time, there was a job that had to be done, I was there to do it. A soldier goes into training. You find yourself in battle and you know the role you're supposed to fulfill."

The HUAC continued to ask questions of this nature. Seeger pointed out: "I feel that in my whole life I have never done anything of any conspiratorial nature and I resent very much and very deeply the implication of being called before this Committee that in some way because my opinions may be different from yours, that I am any less of an American than anyone else. I am saying voluntarily that I have sung for almost every religious group in the country, from Jewish and Catholic, and Presbyterian and Holy Rollers and Revival Churches. I love my country very dearly, and I greatly resent the implication that some of the places that I have sung and some of the people that I have known, and some of my opinions, whether they are religious or philosophical, make me less of an American."

As a result of Seeger's testimony, on 26th July, 1956, the House of Representatives voted 373 to 9 to cite Seeger, Arthur Miller, and six others for contempt. However, Seeger did not come to trial until March, 1961. Seeger defended himself with the words: "Some of my ancestors were religious dissenters who came to America over three hundred years ago. Others were abolitionists in New England in the eighteen forties and fifties. I believe that my choosing my present course I do no dishonor to them, or to those who may come after me." He was found guilty and sentenced to 12 months in prison. After worldwide protests, the Court of Appeals ruled that Seeger's indictment was faulty and dismissed the case.

Pete Seeger told Ruth Schultz in 1989: "Historically, I believe I was correct in refusing to answer their questions. Down through the centuries, this trick has been tried by various establishments throughout the world. They force people to get involved in the kind of examination that has only one aim and that is to stamp out dissent. One of the things I'm most proud of about my country is the fact that we did lick McCarthyism back in the fifties. Many Americans knew their lives and their souls were being struggled for, and they fought for it. And I felt I should carry on. Through the sixties I still had to occasionally free picket lines and bomb threats. But I simply went ahead, doing my thing, throughout the whole period. I fought for peace in the fifties. And in the sixties, during the Vietnam war, when anarchists and pacifists and socialists, Democrats and Republicans, decent-hearted Americans, all recoiled with horror at the bloodbath, we came together."

Un-American Activities Committee in 1955.