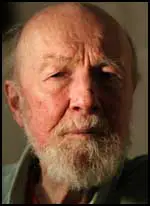

Pete Seeger

Pete Seeger was born in New York City on 3rd May, 1919. He later wrote: "My ancestors came to this country because they didn't want to answer questions put to them by the then Un-English committees. One of them, Elder Brewster, was on the Mayflower with Governor Bradford, one of the leaders of the Plymouth Colony. His descendants that came my way were staunch upholders of independence among the colonists. Not one was a royalist.... These ancestors of mine were all subversives in the eyes of the established government of the British colonies. If they had lost the War of Independence, they might have been hung."

His father, Charles Louis Seeger, was a musicologist who taught at Berkeley University. He held left-wing views and was sympathetic to the International Workers of the World (IWW). Seeger lost his job when he opposed United States involvement in the First World War. Seeger told his dean that Germany and England were both imperialist powers, and as far as he was concerned, they could fight each other to a stalemate. According to his friends, losing his professorship for his activism affected him profoundly.

His mother, Constance de Clyver Edson, also held radical political views and was a follower of Norman Thomas, a pacifist and member of the American Socialist Party, Fellowship of Reconciliation (FOR), and National Civil Liberties Bureau (NCLB) who refused to fight in the war as he believed it was an "immoral, senseless struggle among rival imperialisms". Constance was also a musician and played the violin in concerts.

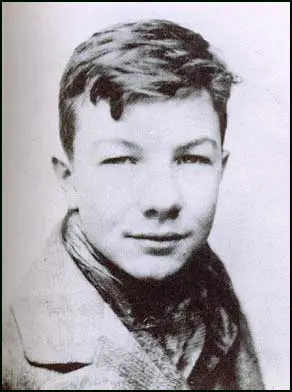

Charles and Constance Seeger and their children moved to Patterson to live with his parents. His father had made a small fortune in sugar-refining in Mexico. Pete Seeger later recalled: "Talk about ivory towers, I grew up in a woodland tower... I knew all about plants and could identify birds and snakes, but I did not know that anti-Semitism existed... My contact with black people was literally nil... If someone asked me what I was going to be when I grew up, I'd say farmer or forest ranger."

Seeger was sent to boarding school at four. In 1927 his parents divorced. Seeger had a difficult relationship with his mother. She was keen for him to take music lessons but at the time he showed little interest in playing the piano or the violin. Seeger admitted: "My father was the one person I really related to. For good or bad, I had very few relationships with anyone else. I was cordial with everybody - I didn't like to fight and I didn't like to argue. My brothers? We got along; but they were much older than me - six and seven years older - and in a different world."

Charles Louis Seeger and his new wife, Ruth Crawford Seeger, went to live in Greenwich Village. He joined the Composers Collective that appeared at the DeGeyter Club. They also sung their songs on picket and unemployment lines. During one holiday his father took him to hear a lecture by Aaron Copland. He was impressed by Copland's enthusiasm and passion. Seeger later recalled: "I got the feeling that here were people out to change the world. The world might be corrupt, but they were confident they could change it."

In 1932 entered high school at Avon Old Farms. During this period Seeger read widely. This included journalists such as Lincoln Steffens, George Seldes, Carl Sandburg and Michael Gold and was an avid reader of New Masses. Seeger started his own newspaper, the Avon Weekly. He got into trouble with his headmaster, Commander Hunter, when he published an anonymous letter on anti-Semitism that had been written by a Jewish student at the school. "There's a lot of talk about democracy and freedom in this country and in the school, but when it comes down to the way people actually act, face it, they don't always live by their pretty words." Under the threat of banning the newspaper, Seeger, named the boy who had written the letter.

Pete Seeger's father became an administered music programs for the Farm Security Administration. In 1935 he moved to Montgomery County, Maryland. During this period, when he was staying with his father, he began listening to local radio and discovered he liked folk music. "I liked the strident vocal tone of the singers, the vigorous dancing. The words of the folk songs had all the meat of life in them. Their humor had a bite, it was not trival. Their tragedy was real, not sentimental. In comparison, most of the pop music of the thirties seemed to be weak and soft, with its endless variations on Baby, baby I need you." Pete purchased a five-string banjo and taught himself to play the instrument.

Seeger went to Harvard University in 1937. He wanted to study journalism but they did not teach the subject so he decided on sociology instead. He was tempted to join the Abraham Lincoln Brigade that was fighting in the Spanish Civil War. He did not like the idea of fighting but insisted that "if someone had offered me a job as a reporter, though, I'd have jumped at it." Therefore he concentrated on raising money for the cause. He also founded his own radical newspaper, The Harvard Progressive, with Arthur Kinoy and joined the Young Communist League.

Seeger was in the same year as John F. Kennedy. However, unlike Kennedy he did not complete his degree. It has been said that whereas Kennedy was Harvard's most famous graduates, Seeger was probably its best-known dropouts. He left university in 1938 and attempted to make a living as a journalist. "College was fine for those who want it, but I was just not interested; I wanted to be a journalist."

In 1939 Charles Seeger introduced his son to Alan Lomax. He arranged for him to meet Molly Jackson, the composer of I Am a Union Woman and Huddie Leadbelly. With their encouragement he began taking his music more seriously. His first concert performance was on 3rd March 1940. It was a benefit for California migrant workers. Other singers on the show included Josh White, Woody Guthrie, Burl Ives, Jackson and Leadbelly. Seeger was especially impressed by Guthrie: "Woody Guthrie just ambled out, offhand and casual... a short fellow complete with a western hat, boots, blue jeans, and needing a shave, spinning out stories and singing songs he'd made up... He was a big piece of my education."

Woody Guthrie, Lee Hayes, Millard Lampell and Pete Seeger

In December 1940 Seeger joined together with Woody Guthrie, Lee Hayes, Pete Hawes and Millard Lampell to form the Almanac Singers. They specialized in songs advocating an anti-war, anti-racism and pro-union philosophy. Lampell later explained: "I was doing all kinds of writing before I hooked up with Pete and Woody and Lee. I had read Lee's satirical stories in the New Republic about his father's circuit-riding days, and he had read my articles there. I hadn't even played an instrument as a kid, let alone thought of writing lyrics. But Lee and I took an apartment together, and the group got going."

David King Dunaway, the author of How Can I Keep From Singing (1985), has argued: "The Almanac Singers didn't want all-expenses-paid trips to Hollywood; union rallies were what they craved. They opposed war and promoted unions the way the early Christians believed in the Church." Performers who sang with the group at various times included Sis Cunningham, Bess Lomax Hawes, Cisco Houston, Josh White, Burl Ives and Sam Gary. The music collective issued a popular record, Talking Union in 1941.

It was claimed that the Almanac Singers were sympathetic to the views of the American Communist Party and gave support to the government of Joseph Stalin. The singer, Billy Bragg, has pointed out: "Seeger was criticised as a Stalin apologist, but he was honest about it and regretted his own naiveté. Like many at that time, he saw that the idealism that seemed to manifest itself in the USSR had been totally undermined by totalitarianism." Seeger told The Washington Post in 1994: “I apologize for once believing Stalin was just a hard driver, not a supremely cruel dictator. I ask people to broaden their definition of socialism. Our ancestors were all socialists: You killed a deer and maybe you got the best cut, but you wouldn’t let it rot, you shared it. Similarly, I tell socialists, every society has a post office and none of them is efficient. No post office anywhere invented Federal Express.”

The Almanac Singers mainly followed the party line and after the Nazi-Soviet Pact sang songs against involvement in the Second World War. They were therefore put in a very difficult situation when Adolf Hitler ordered the invasion of the Soviet Union on 22nd June, 1941. They now stopped singing peace songs and concentrated on other political issues such as The Ballad of Harry Bridges. When J. Edgar Hoover heard about the group he ordered that the members should be investigated for sedition.

The singer, Earl Robinson, often performed with Seeger. "Pete was superb with the banjo... Pete would stand up in front of an audience and really get them going, and in the enthusiasm of the moment, he'd tear off about twelve seconds of totally brilliant cadenza-type banjo; music that would stand up on any concert stage." Millard Lampell later recalled: "He (Pete Seeger) would get up in the morning, and before he'd eat or anything, he'd reach for the banjo and begin to play, sitting on his bed in his underwear... Back then, Pete had enormous energy. He wasn't the greatest banjo player, he didn't have the greatest voice, but there was something catchy about him... It was a time when the left wing was very romantic about America; in literature, these were the days of Carl Sandburg, Archibald MacLeish and Stephen Benet. Then suddenly it was as if the music of America had arrived."

On 7th December, 1941, Pearl Harbor was attacked and the United States entered the war. Alan Lomax warned Seeger that he should bring an end to the Almanac Singers as anti-war songs were not merely inappropriate, they were treasonous. Seeger also had the problem of having a girlfriend, Toshi Ohta, who had a Japanese father. Her father, Takashi Ohta, was arrested by the FBI but he was not interned.

The Almanacs now concentrated on writing anti-Nazi songs. The most successful of these was The Sinking of Reuben James, the story of the ninety-five people drowned in the first American ship torpedoed in the Second World War. They were even hired by the United States Office of War Information to perform for troops as the government understood the value of songs in building morale. As David King Dunaway pointed out: "When the Almanacs had sung peace songs, critics had called it propaganda; now they sang war songs, the government styled it patriotic art." On 14th February, 1942, the Almanacs played for nearly thirty million radio listeners at the opening of a new series, This Is War.

Pete Seeger joined the United States Army Airforce in June 1942. He worked on airplane engines at Kessler Air Force Base in Biloxi, Mississippi. When he was on leave he married Toshi Ohta in a small church in Greenwich Village on 20th July 1943. Soon afterwards he was transferred to Special Services Division based at Fort Meade in Maryland. In 1944 he was sent to Saipan to entertain the troops.

Seeger arrived back in America in 1945. Bess Lomax Hawes pointed out: "When Pete came back from the war he was a very different man. He had matured physically and became a stronger singer. Now he was physically vibrant. He'd always been tense, lean, and bony, but the years of physical activity had put some weight on him. He was as hard as nails... He'd worked for all kinds of audiences and come back with People's Songs in his head and the same burning intensity. He had a national idea in mind now."

On 31st December, 1945, Seeger decided to establish People's Songs Incorporated (PSI). Some of his friends, including Alan Lomax, Lee Hayes, Woody Guthrie, Millard Lampell, Burl Ives, Josh White, Sis Cunningham, Bess Lomax Hawes, Cisco Houston, Moe Asch, Tom Glazer, Sonny Terry, Zilphia Horton and Irwin Silber agreed to support the venture. Seeger was asked in January 1946 what was the purpose of the company: "Make a singing labor movement. I hope to have hundreds, thousands, tens of thousands of union choruses. Just as every church has a choir, why not every union?"

The organization published a weekly newsletter, People's Song Bulletin, with songs, articles, and announcements of future performances. After two months the PSI had over a thousand paid members in twenty states. In the New Masses Seeger pointed out: "When a bunch of people are seen walking down the street singing, it should go almost without saying that they are a bunch of union people on their way home from a meeting... Music, too, is a weapon." Within a few months the organization had two thousand members.

Aaron Copland, Leonard Bernstein, Dorothy Parker, Oscar Hammerstein II, John H. Hammond, Sam Wanamaker and Harold Rome gave permission for their names to be added to the masthead of People's Song Bulletin. Membership continued to increase and Seeger took an office in Times Square. This success was noted by J. Edgar Hoover and he instructed FBI officers to open a file on the PSI. Maurice Duplessis, the Governor of Quebec, ordered that PSI publications to be seized, and declared the song Joe Hill was subversive. When he heard the news Seeger issued a statement that included: "Do you think, Mr. Duplessis, you can escape the judgment of history? Long after the warmakers are relegated to the history books... people's music will be sung by the free peoples of earth."

Seeger was supporter of Henry Wallace and the Progressive Party candidate in the presidential election of 1948. On 30th August, 1948, Seeger and Paul Robeson appeared with Wallace in Burlington, North Carolina. Seeger later recalled: "There were times when a song lightened the atmosphere. I think it probably helped prevent people from getting killed. It was a very - touch and go proposition, that tour. A number of people thought Wallace was going to be assassinated... The police allowed some of the Ku Klux Klan to get away - with throwing things. Once they found out they could get away with that, then they really descended."

David King Dunaway has pointed out: "Monday morning, August 30, 1948, fifteen cars in Wallace's contingent brought Seeger and the candidate to the textile town of Burlington, North Carolina. A grim mood hung over the entourage: The night before, a supporter had been stabbed twice by anti-Wallace crowds. A hostile throng of 2,500 awaited the caravan. It took four policemen to clear the road for the automobiles to reach the public square.... The driver of the lead car, Marge Frantz, was an immediate target. The sight of blacks and whites in the same convertible (the top fortunately rolled up) sent a shock wave through the already excited crowd. A few cars back, Pete sat guarding his banjo and guitar. The angry Southerners crawled onto the hood of his car and peered down inside as it slowed to a halt. The mob started banging on the car doors, and the shell of metal must have seemed awfully thin.

He waited coolly as the crowd pressed in, yelling obscenities and 'Go back to Russia.' No one seemed to be in the mood for a sing-along. According to the plan, Seeger was supposed to leave the car, wait while a mike was positioned, and lead the crowd in group singing. But when he stuck his head out, the eggs started to fly. One hit Wallace, spattering his white shirt. It was clear no mike would be set up... There wasn't even time to tune up, when no amount of banjo picking was going to stop the cold war."

Harry S. Truman and his running mate, Alben W. Barkley, polled more than 24 million popular votes and 303 electoral votes. His Republican Party opponents, Thomas Dewey and Earl Warren, won 22 million popular votes and 189 electoral votes. Storm Thurmond ran third, with 1,169,032 popular and 39 electoral votes. Wallace was last with 1,157,063 votes. Nationally he got only 2.38 per cent of the total vote.

Seeger joined Ronnie Gilbert, Lee Hays and Fred Hellerman to form The Weavers in November 1948. The group took its name from a play by Gerhart Hauptmann, called Die Weber (The Weavers) about a strike in Silesia in 1892. He also invested $1,700 in 17 acres of land overlooking the Hudson River in Beacon, Dutchess County. He built a log cabin there and it became his permanent home for the rest of his life.

They signing a recording deal with Decca and on 4th May, 1950, the group recorded Tzena, Tzena and Goodnight Irene, a song written by Seeger's old friend, Huddie Leadbelly. For censorship reasons the chorus was changed from "I'll get you in my dreams" to "I'll see you in my dreams". The record was a massive hit. Seeger later commented: "I remember laughing when I walked down the street and heard my own voice coming out of a record store." They were offered a weekly national TV spot on NBC and were paid $2,250 a week to appear at the Beacon Theater on Broadway.

The Weavers had a number of hit songs including Wimoweh, The Roving Kind, On Top of Old Smoky, The Midnight Special, Pay Me My Money Down and Darling Corey. In their shows they sung left-wing songs such If I Had a Hammer, that their record company felt that the general public would not accept. Most of his friends said that success did not change Seeger. However, Lee Hays, did say that it increased his "arrogant modesty".

On 6th June, 1950, Harvey Matusow sent a message to the FBI that they should keep a close watch on The Weavers as the leader of the group, Pete Seeger, was a member of the American Communist Party. This was untrue as Seeger had left the party soon after the war. In fact, the agency had been monitoring Seeger since 1940. J. Edgar Hoover now leaked this FBI file to Frederick Woltman, of the New York World Telegram. He published an article revealing that the Weavers were the first musicians in American history to be investigated for sedition.

Roy Brewer, a close friend of Ronald Reagan, was appointed to the Motion Picture Industry Council. Brewer commissioned a booklet entitled Red Channels. Published on 22nd June, 1950, and written by Ted C. Kirkpatrick, a former FBI agent and Vincent Hartnett, a right-wing television producer, it listed the names of 151 writers, directors and performers who they claimed had been members of subversive organisations before the Second World War but had not so far been blacklisted. People listed included Pete Seeger, Larry Adler, Stella Adler, Leonard Bernstein, Marc Blitzstein, Joseph Bromberg, Lee J. Cobb, Aaron Copland, John Garfield, Howard Da Silva, Dashiell Hammett, E. Y. Harburg, Lillian Hellman, Burl Ives, Zero Mostel, Arthur Miller, Betsy Blair, Dorothy Parker, Philip Loeb, Joseph Losey, Anne Revere, Gale Sondergaard, Howard K. Smith, Louis Untermeyer and Josh White.

Three days after the booklet was published the Korean War erupted. The list of entertainers were now seen as America's mortal enemies. NBC immediately cancelled its contract with the Weavers. Although the Weavers had sold over four million records, radio stations now stopped playing their music. They were also banned from appearing on national television. However, despite this attempt to take them out of circulation, in 1951 they still had hits with Kisses Sweeter than Wine and So Long It's Been Good to Know You.

On 6th February, 1952, Harvey Matusow testified in front of the House of Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC) that Seeger was a member of the American Communist Party. Matusow admitted in his autobiography, False Witness (1955) that this was untrue but Seeger said this ended the career of The Weavers: "Matusow's appearance burst like a bombshell... We had started off singing in some very flossy night-clubs... Then we went lower and lower as the blacklist crowded us in. Finally, we were down to places like Daffy's Bar and Grill on the outskirts of Cleveland." Despite not being a member of the party Seeger continued to describe himself as a “communist with a small ‘c.’ ”

It was another three years before Seeger was called before the HUAC. Frank Donner, a lawyer who defended several people who were called before the HUCA, wrote in The Un-Americans (1961): "He knows that the Committee demands his physical presence in the hearing room for no reason other than to make him a target of its hostility, to have him photographed, exhibited and branded... He knows that the vandalism, ostracism, insults, crank calls and hate letters that he and his family have already suffered are but the opening stages of a continuing ordeal... he is tormented by the awareness that he is being punished without valid cause, and deprived, by manipulated prejudice, of his fundamental rights as an American."

Seeger's lawyer, Paul Ross, advised him to use the Fifth Amendment defence (the right against self-incrimination). In the year of Seeger's subpoena, the HUAC called 529 witnesses and 464 (88 per cent) remained silent. Seeger later recalled: "The expected move would have been to take the Fifth. That was the easiest thing, and the case would have been dismissed. On the other hand, everywhere I went, I would have to face 'Oh, you're one of those Fifth Amendment Communists...' I didn't want to run down my friends who did use the Fifth Amendment but I didn't choose to use it."

Seeger had been struck by something that I.F. Stone had written in 1953: "Great faiths can only be preserved by men willing to live by them (HUAC's violation of the First Amendment) cannot be tested until someone dares invite prosecution for contempt." Seeger decided that he would accept Stone's challenge, and use the First Amendment defence (freedom of speech) even though he knew it would probably result in him being sent to prison. Seeger told Paul Ross : "I want to get up there and attack these guys for what they are, the worst of America". Ross warned him that each time the HUCA found him in contempt, he was liable to a year in jail.

The first day of the new HUAC hearings took place on 15th August 1955. Most of the witnesses were excused after taking the Fifth Amendment. Seeger's friend, Lee Hays, also evoked the Fifth Amendment on the second day of the hearings and he was allowed to go unheeded. Seeger was expected to follow his example but instead he answered their questions. When asked for details of his occupation, Seeger replied: "I make my living as a banjo picker - sort of damning in some people's opinion." However, when Gordon Scherer, a sponsor of the John Birch Society, asked him if he had performed at concerts organized by the American Communist Party he refused to answer.

Un-American Activities Committee in 1955.

Francis Walter, the chairman of the House of Un-American Activities Committee, told Seeger: "I direct you to answer". Seeger replied: "I am not going to answer any questions as to my association, my philosophical or religious beliefs or my political beliefs, or how I voted in any election or any of these private affairs. I think these are very improper questions for any American to be asked, especially under such compulsion as this." Seeger later recalled: "I realized that I was fitting into a necessary role... This particular time, there was a job that had to be done, I was there to do it. A soldier goes into training. You find yourself in battle and you know the role you're supposed to fulfill."

The HUAC continued to ask questions of this nature. Seeger pointed out: "I feel that in my whole life I have never done anything of any conspiratorial nature and I resent very much and very deeply the implication of being called before this Committee that in some way because my opinions may be different from yours, that I am any less of an American than anyone else. I am saying voluntarily that I have sung for almost every religious group in the country, from Jewish and Catholic, and Presbyterian and Holy Rollers and Revival Churches. I love my country very dearly, and I greatly resent the implication that some of the places that I have sung and some of the people that I have known, and some of my opinions, whether they are religious or philosophical, make me less of an American."

As a result of Seeger's testimony, on 26th July, 1956, the House of Representatives voted 373 to 9 to cite Seeger, Arthur Miller, and six others for contempt. However, Seeger did not come to trial until March, 1961. Seeger defended himself with the words: "Some of my ancestors were religious dissenters who came to America over three hundred years ago. Others were abolitionists in New England in the eighteen forties and fifties. I believe that my choosing my present course I do no dishonor to them, or to those who may come after me." He was found guilty and sentenced to 12 months in prison. After worldwide protests, the Court of Appeals ruled that Seeger's indictment was faulty and dismissed the case.

Seeger told Ruth Schultz in 1989: "Historically, I believe I was correct in refusing to answer their questions. Down through the centuries, this trick has been tried by various establishments throughout the world. They force people to get involved in the kind of examination that has only one aim and that is to stamp out dissent. One of the things I'm most proud of about my country is the fact that we did lick McCarthyism back in the fifties. Many Americans knew their lives and their souls were being struggled for, and they fought for it. And I felt I should carry on. Through the sixties I still had to occasionally free picket lines and bomb threats. But I simply went ahead, doing my thing, throughout the whole period. I fought for peace in the fifties. And in the sixties, during the Vietnam war, when anarchists and pacifists and socialists, Democrats and Republicans, decent-hearted Americans, all recoiled with horror at the bloodbath, we came together."

His friend, Don McLean, explained how this case severely damaged his career: "Pete went underground. He started doing fifty dollar bookings, then twenty-five dollar dates in schoolhouses, auditoriums, and eventually college campuses. He definitely pioneered what we know today as the college circuit. He persevered and went out like Kilroy, sowing seeds at a grass-roots level for many, many years. The blacklist was the best thing that happened to him; it forced him into a situation of struggle, which he thrived on." Seeger's concerts were often picketed by the John Birch Society and other right-wing groups. He later recalled: “All those protests did was sell tickets and get me free publicity. The more they protested, the bigger the audiences became.”

Although freed from prison, the blacklisting of Seeger continued. Seeger's songs written and performed during this period often reflected his left-wing views and included We Shall Overcome, Where Have All the Flowers Gone, If I Had a Hammer, Guantanamera, The Bells of Rhymney and Turn, Turn, Turn. Seeger's biographer, David King Dunaway, has argued: "Pete's best political songs evoked not the bitterness of repression but the glory of its solution, the potential beauty of a world remade. His music couldn't overthrow a government, he had come to realize, but the children he sang for might begin the process."

Jon Pareles has pointed out in the New York Times: "Seeger was signed to a major label, Columbia Records, in 1961, but he remained unwelcome on network television. Hootenanny, an early-1960s show on ABC that capitalized on the folk revival, refused to book Mr. Seeger, causing other performers (including Bob Dylan, Joan Baez and Peter, Paul and Mary) to boycott it. Hootenanny eventually offered to present Mr. Seeger if he would sign a loyalty oath. He refused."

Seeger remained active in the protest movement. The Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee adopted his song, We Shall Overcome, during the 1960 student sit-ins a restaurants which had a policy of not serving black people. The students were often physically assaulted, but following the teachings of Martin Luther King they did not hit back. This non-violent strategy was adopted by black students all over the Deep South. Within six months these sit-ins had ended restaurant and lunch-counter segregation in twenty-six southern cities. Student sit-ins were also successful against segregation in public parks, swimming pools, theaters, churches, libraries, museums and beaches. The SNCC also sung the song during the 1961 Freedom Rides.

As well as the Civil Rights Movement Seeger was also involved in protests against the Vietnam War. As a result television stations refused to end the blacklisting of Seeger. Artists that had been inspired by the work of Seeger such as Bob Dylan, Joan Baez, Tom Paxton, and Harry Belafonte, protested against this decision. It was not until 1967 that the Smothers Brothers managed to negotiate a guest appearance for Seeger on their TV program, The Smothers Brothers Comedy Hour.

Pete Seeger and his wife Toshi Ohta, continued to live in a log cabin overlooking the Hudson River in Beacon, Dutchess County. They co-founded both the Hudson River Sloop Clearwater and its related musical offshoot, The Great Hudson River Revival (also known as the Clearwater Festival).They used the festival to rally public support for cleaning up the Hudson River. The Clearwater Festival now attracts more than 15,000 attendees to Croton Point Park each summer.

In 1979 The Weavers reunited for a concert at Carnegie Hall, filmed for the much-admired documentary, The Weavers: Wasn't That a Time (1982). Paul Buhle has commented that "the event found the media, including the New York Times, downright sentimental and perhaps a little guilty toward the formerly persecuted artists." Seeger continued to perform, often with his grandson, Tao Rodríguez-Seeger.

Seeger told The Washington Post in 1994: “I apologize for once believing Stalin was just a hard driver, not a supremely cruel dictator. I ask people to broaden their definition of socialism. Our ancestors were all socialists: You killed a deer and maybe you got the best cut, but you wouldn’t let it rot, you shared it. Similarly, I tell socialists, every society has a post office and none of them is efficient. No post office anywhere invented Federal Express.”

In 2006, Bruce Springsteen helped introduce Seeger to a new generation when he recorded We Shall Overcome: The Seeger Sessions, an album of 13 songs popularized by Seeger. In 2009 Springsteen introduced Seeger at a concert to celebrate his 90th birthday: "He's gonna look a lot like your granddad that wears flannel shirts and funny hats. He's gonna look like your granddad if your granddad can kick your ass. At 90, he remains a stealth dagger through the heart of our country's illusions about itself."

Pete Seeger, aged 94, died on 27th January, 2014. President Barack Obama said in a statement. “He believed in the power of community - to stand up for what’s right, speak out against what’s wrong, and move this country closer to the America he knew we could be. Over the years, Pete used his voice - and his hammer - to strike blows for worker’s rights and civil rights; world peace and environmental conservation. And he always invited us to sing along. For reminding us where we come from and showing us where we need to go, we will always be grateful to Pete Seeger.”

Primary Sources

(1) David King Dunaway, How Can I Keep From Singing (1985)

Pete Seeger and Paul Robeson were asked to tour with Wallace. Sometimes Toshi came along, bringing Mika (their new baby) in a bassinet. The campaign made a clean test of the power of song. "There were times when a song lightened the atmosphere," Seeger later reflected. "I think it probably helped prevent people from getting killed. It was a very - touch and go proposition, that tour. A number of people thought Wallace was going to be assassinated... The police allowed some of the Ku Klux Klan to get away - with throwing things. Once they found out they could get away with that, then they really descended."

"I remember a courthouse in Mississippi, where an absolutely livid white Southerner stood in front of me and said, "Bet you can't sing Dixie" I said, "Sure I can, if you'll sing it with me." The Dixiecrat stood there furious, unsure whether to sing or not, while Seeger sang not one, but three verses he had learned in the army.

By the end of August, the campaign was clearly sinking. HUAC had just finished a brutal attack on the Progressive Party; Harry Dexter White, a former Wallace aide, had a heart attack and died from the strain. Most of the CIO unions had fled the campaign, leaving the CP virtually alone in its support. Then Wallace decided, against his advisers' pleas, to campaign through the South, bringing Seeger to warm up the crowds and a black woman as his secretary.

Monday morning, August 30, 1948, fifteen cars in Wallace's contingent brought Seeger and the candidate to the textile town of Burlington, North Carolina. A grim mood hung over the entourage: The night before, a supporter had been stabbed twice by anti-Wallace crowds. A hostile throng of 2,500 awaited the caravan. It took four policemen to clear the road for the automobiles to reach the public square. One of them said, "Mr. Wallace, I hope you're planning to leave soon. I don't think we can handle this crowd." A Klan truck had preceded Wallace, passing out eggs and tomatoes.

The driver of the lead car, Marge Frantz, was an immediate target. The sight of blacks and whites in the same convertible (the top fortunately rolled up) sent a shock wave through the already excited crowd. A few cars back, Pete sat guarding his banjo and guitar. The angry Southerners crawled onto the hood of his car and peered down inside as it slowed to a halt. The mob started banging on the car doors, and the shell of metal must have seemed awfully thin.

He waited coolly as the crowd pressed in, yelling obscenities and "Go back to Russia." No one seemed to be in the mood for a sing-along. According to the plan, Seeger was supposed to leave the car, wait while a mike was positioned, and lead the crowd in group singing. But when he stuck his head out, the eggs started to fly. One hit Wallace, spattering his white shirt. It was clear no mike would be set up. Seeger hurriedly introduced Henry Wallace.

"Whenever Wallace attempted to speak, he was greeted by an unfriendly roar and had no chance to make himself heard above it," historian Curtis Macdougall wrote. "He waited as an occasional egg or tomato splashed on the street near him. Then he suddenly committed an act which, in retrospect, seems comparable to putting one's head into a lion's mouth. He reached out and grabbed a bystander.

(2) Peter Seeger testified in front of the House of Un-American Activities Committee on 15th August, 1955 but was unwilling to name other members of the various left-wing groups that he had belonged to over the years.

I feel that in my whole life I have never done anything of any conspiratorial nature and I resent very much and very deeply the implication of being called before this Committee that in some way because my opinions may be different from yours, that I am any less of an American than anyone else.

I am saying voluntarily that I have sung for almost every religious group in the country, from Jewish and Catholic, and Presbyterian and Holy Rollers and Revival Churches. I love my country very dearly, and I greatly resent the implication that some of the places that I have sung and some of the people that I have known, and some of my opinions, whether they are religious or philosophical, make me less of an American.

(2) Pete Seeger, speech before being sentenced to 10 years imprisonment for contempt of Congress (3rd April, 1961)

Some of my ancestors were religious dissenters who came to America over three hundred years ago. Others were abolitionists in New England in the eighteen forties and fifties. I believe that my choosing my present course I do no dishonor to them, or to those who may come after me.

(3) Don McLean explained what happened to Peter Seeger after being blacklisted.

Pete went underground. He started doing fifty dollar bookings, then twenty-five dollar dates in schoolhouses, auditoriums, and eventually college campuses. He definitely pioneered what we know today as the college circuit. He persevered and went out like Kilroy, sowing seeds at a grass-roots level for many, many years. The blacklist was the best thing that happened to him; it forced him into a situation of struggle, which he thrived on.

(4) Pete Seeger, interviewed by Ruth Schultz in 1989.

Historically, I believe I was correct in refusing to answer their questions. Down through the centuries, this trick has been tried by various establishments throughout the world. They force people to get involved in the kind of examination that has only one aim and that is to stamp out dissent. One of the things I'm most proud of about my country is the fact that we did lick McCarthyism back in the fifties. Many Americans knew their lives and their souls were being struggled for, and they fought for it. And I felt I should carry on.

Through the sixties I still had to occasionally free picket lines and bomb threats. But I simply went ahead, doing my thing, throughout the whole period. I fought for peace in the fifties. And in the sixties, during the Vietnam war, when anarchists and pacifists and socialists, Democrats and Republicans, decent-hearted Americans, all recoiled with horror at the bloodbath, we came together.

(5) Billy Bragg, The Guardian (28th January, 2014)

Why did Pete Seeger, who has died aged 94, matter? Because for over 75 years he stood true to his original vision, he never wavered. Even when his beliefs had a huge impact on his life and career: he never sold out. He wasn't just a folk singer, or an activist: he was both.

Pete believed that music could make a difference. Not change the world, he never claimed that – he once said that if music could change the world he'd only be making music – but he believed that while music didn't have agency, it did have the power to make a difference.

Shaped by that 30s leftwing mentality of the New Deal, Pete saw songs as political acts – for him these were people's songs – ways for the working class to express themselves. It doesn't matter that this was later superseded by rock and roll and changed beyond recognition – Seeger was there at the beginning and he never stopped.

When you shook his hand you knew you were shaking hands with someone who had crossed America with Woody Guthrie, who had marched with Martin Luther King and who had stared down McCarthyism – he embodied those great struggles. Other artists, like Bruce Springsteen, have recognised that and have seen Seeger as a touchstone, as someone who showed that songs were more than just making records and doing gigs. By choosing his repertoire carefully, Seeger brought the work of artists who had never achieved great success in their lifetimes to a mainstream audience. In the 1950s he put songs by Leadbelly and Woody Guthrie into the charts and royalties into the hands of their families.

He was already old the first time I met him – we were at a Canadian folk festival, where – as well as doing my own spot – I was invited to take part in a workshop where various artists played songs together. I agreed to take part in a Woody Guthrie workshop and when I turned up I saw that I was set to play with Ramblin' Jack Elliott – Woody's right-hand man – Arlo Guthrie and Seeger. I thought: I'm completely busted here. I busked it and at the end Seeger stood up and in his reedy voice he started to sing This Land is Your Land. Guthrie and Elliot did a verse, but when it came to my turn I had to say sorry folks – that land was not my land – we just don't learn this song in England. Seeger was so supportive and understanding.

Another time, when I was with Seeger and Arlo Guthrie again, this time to see Woody Guthrie inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, Seeger – who must have been in his 70s – disappeared. When I turned around he was lying on his back, elbows under his hips, cycling his legs in the air. He was just something else.

Seeger was criticised as a Stalin apologist, but he was honest about it and regretted his own naiveté. Like many at that time, he saw that the idealism that seemed to manifest itself in the USSR had been totally undermined by totalitarianism. He wasn't afraid to admit he had been wrong, and – despite the insults people threw at him – he was a patriot. He believed in America and liberty – but not just in the liberty to make money, his idea of freedom was broader than that.

He was also criticised for turning against his protege Bob Dylan, but I think that was misunderstood. Yes, he did try to get Dylan to turn down his amplifier at Newport in 65. But the thing that angered Seeger was not the fact that Dylan had gone electric – he'd applauded Muddy Waters electric set earlier that day – he was angry because he couldn't hear the lyrics. The words, the context, was everything. Seeger, who had faced a spell in prison because of the words he sang, had more reason to be angry than most.

(6) Bart Barnes, The Washington Post (28th January, 2014)

At a Kennedy Center Honors ceremony in 1994, President Bill Clinton described Mr. Seeger as “an inconvenient artist who dared to sing things as he saw them.” The news media sometimes called him a “pied piper of musical dissent.” By the dawn of the new millennium, Mr. Seeger had become the widely acknowledged, if unofficial, grand old man of American folk music.

He regarded folk songs as music meant to be sung by crowds and bonded with audiences around the world by inviting them to sing along with him. During a performance at Moscow’s Tchaikovsky Concert Hall, he led an audience of 10,000 Russians in a four-part harmony of “Michael, Row the Boat Ashore.”

“I just tap out a beat, pick a few chords and say, ‘Come on, you folks know this old tune.’ Pretty soon the audience’ll be singing the song to me,” Mr. Seeger told the Chicago Tribune in 1994.

“You can’t sit idle at a Pete Seeger concert,” folk-music collector and performer Ralph Rinzler wrote in The Washington Post in 1972. “Audiences for 30 years have sung, clapped and risen to their feet with enthusiasm. Pete strides onstage, loosens his tie, picks the five-string, adding other instruments as he talks, spins yarns, preaches and sings songs of the nation’s and the world’s people — new ballads, old ones, lyrical laments and hard driving, keen-edged cutters.”

Whether leading a singalong of college students or performing in a formal concert, Mr. Seeger said, he tried to re-create the atmosphere in which his songs were first sung. He sang in a light, pleasing baritone. His goal, he said, was “to put a song on people’s lips, instead of just in their ears.”

He helped bring dozens of classics into the idiom of popular folk music. These included Guthrie’s “This Land Is Your Land” and “So Long, It’s Been Good to Know Yuh,” Lead Belly’s “Midnight Special,” the folk song “On Top of Old Smoky,” the Hebrew song “Tzena, Tzena, Tzena,” the Zulu hit “Wimoweh” and the likes of “Turn, Turn, Turn,” “Guantanamera,” the nonsense song “I Know an Old Lady (Who Swallowed a Fly)” and “Waist Deep in the Big Muddy,” which became popular as a protest song during the Vietnam War era.

(7) Jon Pareles, New York Times (28th January, 2014)

Planning to be a journalist, Mr. Seeger attended Harvard, where he founded a radical newspaper and joined the Young Communist League. After two years he dropped out and went to New York City, where Alan Lomax introduced him to the blues singer Huddie Ledbetter, known as Lead Belly. Lomax also helped Mr. Seeger find a job cataloging and transcribing music at the Archive of American Folk Song at the Library of Congress.

Mr. Seeger met Guthrie, a songwriter who shared his love of vernacular music and agitprop ambitions, in 1940, when they performed at a benefit concert for migrant California workers. Traveling across the United States with Guthrie, Mr. Seeger picked up some of his style and repertory. He also hitchhiked and hopped freight trains by himself, learning and trading songs.

When he returned to New York later in 1940, Mr. Seeger made his first albums. He, Millard Lampell and Hays founded the Almanac Singers, who performed union songs and, until Germany invaded the Soviet Union, antiwar songs, following the Communist Party line. Guthrie soon joined the group.

During World War II the Almanac Singers’ repertory turned to patriotic, anti-fascist songs, bringing them a broad audience, including a prime-time national radio spot. But the singers’ earlier antiwar songs, the target of an F.B.I. investigation, came to light, and the group’s career plummeted.

Before the group completely dissolved, however, Mr. Seeger was drafted in 1942 and assigned to a unit of performers. He married Toshi-Aline Ohta while on furlough in 1943. She would become essential to his work: he called her “the brains of the family.”

When he returned from the war he founded People’s Songs Inc., which published political songs and presented concerts for several years before going bankrupt. He also started his nightclub career, performing at the Village Vanguard in Greenwich Village. Mr. Seeger and Paul Robeson toured with the campaign of Henry Wallace, the Progressive Party presidential candidate, in 1948.

(8) Paul Buhle, The Guardian (28th January, 2014)

In 1948, together with Lee Hays and other veterans of the Almanacs, Seeger formed the Weavers. A brief triumph followed. In 1950 they had a multimillion sales chart success with Goodnight, Irene – first popularised by Lead Belly (Huddie Ledbetter) – and a string of other hits followed including So Long, The Roving Kind, On Top of Old Smokey and Kisses Sweeter Than Wine. They were one of the most successful musical acts in America.

Then came the blacklist. The Weavers were banned from radio and television, and even some concert halls. With their scheduled appearances and commercial recording contracts cancelled, the group dissolved in 1953.

On Christmas Eve 1955 the Weavers, back for one concert, appeared at Carnegie Hall, New York. The event was packed out. But in that time Seeger retreated to the small, leftwing world of summer camps and radical unions, for which he performed and recorded steadily. Most notable in retrospect was his music for children: American Game and Activity Songs for Children (1962) included such numbers as Skip to My Lou and Yankee Doodle.

In the 1960s came the folksong revival, and later the folk-rock boom caught up with him. Covers of songs he wrote or recorded became global hits. There was most notably Peter, Paul and Mary – but also the Kingston Trio and Trini Lopez – with If I Had a Hammer and Where Have All the Flowers Gone? Meanwhile, his rendition of We Shall Overcome became a virtual anthem for the civil rights movement of the early 1960s, and Seeger marched and provided entertainment for numerous desegregationist demonstrations.

That newer generation of commercial folk musicians owed him a deep debt: Peter, Paul and Mary regarded themselves as the Weavers' successors, and singers from Joan Baez and Judy Collins to Joni Mitchell, Arlo Guthrie and Bob Dylan – a self-described disciple of Woody Guthrie – appeared on stage with Seeger and honoured him with tributes. If I Had a Hammer, written by Seeger and Lee Hayes for the Almanacs in 1950, seemed to express the idealism of the younger generation for revived liberalism and even for the martyred President John F Kennedy.