On this day on 11th January

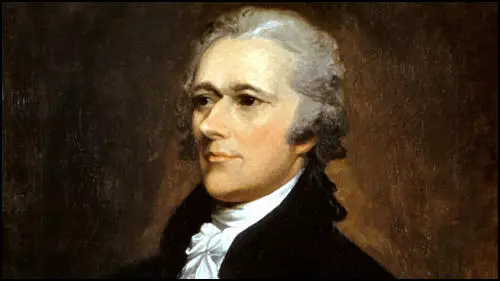

On this day in 1757 Alexander Hamilton was born on the island of Nevis, British West Indies. Hamilton moved to the United States in 1772 and was educated at King's College, New York City. Hamilton developed strong political views and wrote a series of pamphlets in defence of the rights of the colonies against Britain.

Hamilton joined the Continental Army in 1776 and became captain of artillery. He also served as aide-de-camp to General George Washington.

After the war Hamilton studied law and eventually became a leading lawyer in New York. He served as a member of the Continental Congress in 1782 and 1783. Along with John Jay and James Madison he co-authored The Federalist. Hamilton also served in the New York State Assembly.

George Washington was unanimously elected as the first President of the United States and was inaugurated on 30th April, 1789, in New York City. Washington appointed Thomas Jefferson as his Secretary of State and Hamilton as Treasury Secretary. John Adams served as Vice President under Washington.

Washington was unanimously reelected in 1792 but by this time the government was not so united and there were serious disagreements between Jefferson's Democratic Republicans and Hamilton's Federalists. Washington tended to favour the Federalists and with the Democratic Republicans gaining increasing support, he decided not to seek a third term and retired from office on 3rd March, 1797.

John Adams now replaced Washington and Thomas Jefferson became the new Vice President. Although Adams was the leader of the Federalists, he rejected the suggestions of Alexander Hamilton to declare war on France. He did however support the Aliens and Sedition Acts, that intended to frighten foreign agents out of the country. However, his decision to send a peace mission to France made him unpopular and united his opponents against him.

In 1804 Aaron Burr asked Hamilton to support his campaign to become Governor of New York. Hamilton refused saying that Burr was "a man of irregular and insatiable ambition... who ought not be trusted with the reins of government." Burr was furious and challenged Hamilton to a duel in Weekauken, New Jersey. Hamilton accepted and on 11th July, 1804 was shot by Burr. Hamilton died the following day.

On this day in 1852 Elizabeth Sharples died at her home, 12 George Street, Hackney.

Elizabeth Sharples was one of six children born to Ann and Richard Sharples, a manufacturer, in Bolton in 1803. The children received a good education, and Eliza attended boarding-school until she was about twenty. Sharples held conservative views until she began reading The Republican in 1830. She wrote to its editor, Richard Carlile, and after "a rapid exchange of correspondence in which admiration turned to ardent love, she determined to share his work".

Even before he had met Sharples in person, Carlile anticipated that she would become "my daughter, my sister, my friend, my companion, my wife, my sweetheart, my everything".

Richard Carlile published an article in his new newspaper, The Prompter, in support of agricultural labourers campaigning against wage cuts. Carlile's advice to the labourers was "to go on as you have done". This was interpreted by the authorities as a seditious call to arms. Carlile was arrested and charged with seditious libel and appeared at the Old Bailey in January 1831. Carlile argued that "neither in deed, nor in word, nor in idea, did I ever encourage acts of arson or machine breaking".

The court was not convinced by his arguments and Carlile was found guilty of seditious libel and received a sentence of two years' imprisonment and a large fine which he refused to pay, thereby extending the sentence by a further six months. While in prison he continued to write articles for radical newspapers and pamphlets such as New View of Insanity (1831).

In January 1832 Elizabeth Sharples moved to London and visited Carlile in prison. Carlile had always campaigned for women's rights and he invited her to speak at his Blackfriars Rotunda. Several times a week speakers delivered "attacks on the superstitions of Christianity, which Carlile had now identified as the single most obdurate opposition to reform and liberation". The Rotunda became an important centre for working-class dissent and political reform. Speakers included William Cobbett, Henry 'Orator' Hunt, Robert Owen, Daniel O'Connell, Robert Taylor and John Gale Jones. It is reported that at one meeting calling for parliamentary reform, drew a crowd of over 2,000 people.

Billed as "the first Englishwoman to speak publicly on matters of politics and religion" she gave her first talk on 29th January 1832. The Times reported that she was "pretty, with a good figure and genteel manners" and dressed very well. Sharples pointed out in her speech: "I will set before my sex the example of asserting an equality for them with their present lords and masters, and strive to teach all, yes, all, that the undue submission, which constitutes slavery, is honourable to none; while the mutual submission, which leads to mutual good, is to all alike dignified and honourable." "Cast in the role of the Egyptian goddess Isis, she stood on the stage of the theatre, the floor strewn with whitethorn and laurel, and delivered lectures on mystical religion and women's rights."

Elizabeth Sharples was appointed as editor of a new radical weekly publication, Isis. She gave two lectures every Sunday (at sixpence for the pit and boxes, one shilling for the gallery), on Monday evenings (for half-price). She also gave a free lecture on Friday evenings to accommodate those unable to afford the entry charges.

Not everybody enjoyed her speeches. One man wrote to a national newspaper attacking the idea of a woman speaking in public: "Elizabeth Sharples is a female who exhibits herself in so unfeminine a manner... So utterly illiterate is the poor creature, that she cannot yet read what is set down for her with any degree of intelligibility... with her ignorance and unconquerable brogue... her lecturing is almost as ludicrous as it is painful to witness."

Richard Carlile supported Sharples in her campaign for women's rights: "I do not like the doctrine of women keeping at home, and minding the house and the family. It is as much the proper business of the man as the woman; and the woman, who is so confined, is not the proper companion of the public useful man." Edward Royle adds that "this just about sums up the position of women in the radical movement". Even if a woman was emancipated she was expected to be the "proper companion of the public useful man".

Elizabeth Sharples argued in her newspaper articles that Christianity was the chief barrier to the dissemination of knowledge; by denying the people education, priests were denying man's liberty. She suggested that passive and non-resistance was seen as the "doctrine of priesthood".

Sharples was Carlile's greatest supporter while he was in prison. She used the Rotunda platform" to castigate the priesthood, expose religious superstition and denigrate established authority". She promised "sweet revenge" on those responsible for the "incarceration of Carlile". She visited him in prison and began a sexual relationship.

In 1832 Jane Carlile moved out of the family home and started a bookshop of her own. In April 1833 Elizabeth Sharples gave birth to a son, Richard Sharples. Carlile realized that he would have to acknowledge their relationship, and thereupon declared that he and Eliza were joined in a "moral marriage".

Elizabeth Sharples had the task of running the Blackfriars Rotunda while Carlile was in prison. In February 1832, she reported that £1,000 was needed to keep the venture open, to cover rent, taxes, lights and repairs. At the same time there had been a reduction in audiences. She admitted that she had lost the support of the radical community: "I believe I stand alone in the country, as a modern Eve, daring to pluck the fruit of the tree, and to give it to timid, sheepish man. I have received kindnesses and encouragements from a few ladies since my appearance in the metropolis, but how few."

In August 1833, Richard Carlile was released from prison.The couple lived on the corner of Bouverie Street and Fleet Street. Richard Sharples died of smallpox in October 1833. Another son, Julian Hibbert, was born in September 1834. In November 1835 they took a seven-year lease on a cottage in Enfield Highway, where shortly afterwards a daughter, Hypatia, was born. A fourth child, Theophila, followed a year later.

Elizabeth accompanied Richard Carlile on his lecture tours. His biographer, Philip W. Martin, pointed out: "Carlile's position was shifting radically. While it is clear that he never retreated to orthodoxy, his increasing use of Christian rhetoric and his own claims for himself as a Christian were a far cry from the radicalism of his early years. Carlile still propounded a sceptical, rational view of religion, but his allegorical readings had diminished to a single interpretation of Christianity in which he saw Christ and the resurrection as the rebirth of the soul of reason in humankind".

Richard Carlile was still capable of drawing large crowds (1500 people in Leeds in 1839, and 3000 people in Stroud in 1842), it was clear that most radicals rejected his religious views and were attracted to the political arguments of Chartism. He was also in poor health and he died of a bronchial infection on 10th February 1843. As he had dedicated his body to science it was taken to St Thomas's Hospital before his burial at Kensal Green Cemetery in London on 26th February.

At first the family was supported by Sophia Chichester, who arranged for Elizabeth Sharples to take charge of the sewing-room at the Alcott House in Ham, the home of a utopian spiritual community and progressive school. After a few months a small legacy from an aunt enabled her to set up on her own, letting apartments and maintaining her family by her needlework.

In 1849, Elizabeth Sharples set up a coffee and discussion room at 1 Warner Place, Hackney Road, in which to advocate radical freethought and women's rights. Charles Bradlaugh visited her and described her as "looking like a queen" but she was "no good at serving coffee". It is reported that she said "all Reform will be found to be inefficient that does not embrace the Rights of Women".

On this day in 1858 Margaret Jones, the daughter of the classical scholar, Rev. Timothy Jones, was born in Leicester. Margaret was the only daughter in a family of five sons. Her father, the vicar of St Margaret's Church, taught her Latin and Greek with her brothers. She was later educated at a High Church convent school and a Paris finishing school.

In 1880 Margaret became a teacher at South Hampstead High School for Girls. She also started on a degree at St Andrews University, which she eventually obtained. Interested in women's rights she became involved in the campaign in favour of the Married Women's Property Act.

On 18th April 1884 she married the radical journalist, Henry Nevinson, who she had known since childhood. Initially they lived in Whitechapel and both worked at Toynbee Hall. The couple had one daughter, Mary Nevinson, a talented musician, and one son, the successful painter Christopher Nevinson. After the birth of Christopher she suffered from post-natal depression.

Margaret Nevinson did charity work and and helped with St Jude's Girls' Club. In 1887 the Nevinson's moved to Hampstead (4 Downside Crescent) and for a while at Hampstead High School. According to her biographer, Angela V. John she was "always a pioneer, from her shingled hair and hatred of lace curtains to her espousal of modern art, European outlook, and commitment to social justice." Nevinson was a school manager in the East End, then for the London County Council. In 1904 she became a Poor Law Guardian. She took a particular interest in the impact of the poor law on women from working-class backgrounds.

Nevinson was a great advocate of women's suffrage. She was a member of a variety of groups including the National Union of Suffrage Societies, the Church League for Women's Suffrage and the Women's Writers Suffrage League. Her husband, Henry Nevinson, shared her views and along with Laurence Housman, Charles Corbett, Henry Brailsford, C. E. M. Joad, Israel Zangwill, Hugh Franklin, Charles Mansell-Moullin, was a founder of the Men's League For Women's Suffrage.

However, in 1906, frustrated by the NUWSS lack of success, she joined the Women's Social and Political Union (WSPU), an organisation established by Emmeline Pankhurst and her three daughters, Christabel Pankhurst, Sylvia Pankhurst and Adela Pankhurst. The main objective was to gain, not universal suffrage, the vote for all women and men over a certain age, but votes for women, “on the same basis as men.”

In 1907 Nevinson began to to question the leadership of Emmeline Pankhurst and Christabel Pankhurst. These women objected to the way that the Pankhursts were making decisions without consulting members. They also felt that a small group of wealthy women like Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence, Clare Mordan and Mary Blathwayt were having too much influence over the organisation. In the autumn of 1907, Teresa Billington-Greig, Elizabeth How-Martyn, Dora Marsden, Helena Normanton and Charlotte Despard and seventy other members of the WSPU left to form the Women's Freedom League (WFL). Nevinson became treasurer of the Hampstead branch.

In 1911 Edith Craig of the Actresses' Franchise League, established the Pioneer Players. Under her leadership this society became internationally known for promoting women's work in the theatre. Ellen Terry was president of the Pioneer Players and Christabel Marshall contributed as dramatist, translator, actor and a member of the advisory and casting committees. One of the first productions of the group was In the Workhouse, a play written by Margaret Nevinson. The play, based on a true story, told of how a man who used the law to keep his wife in the workhouse against her will. As a result of the play, the law was changed in 1912.

Nevinson wrote several pamphlets published by the including A History of the Suffrage Movement: 1908-1912 (1912), Ancient Suffragettes (1913) and The Spoilt Child and the Law (1913). She also contributed articles to the Women's Freedom League journal, The Vote. It was used to inform the public of WFL campaigns such as the refusal to pay taxes and to fill in the 1911 Census forms.

Henry Nevinson was spending more and more time away from the family home. He later recalled that he endured a "dismal marriage". He argued that they were incompatible as she was "by nature and tradition, catholic and conservative, always inclined to contradict me on every point and all occasions." He admitted that he "thrived on intimate friendships" but she liked "few men and fewer women". He noted that his wedding anniversary reminded him only of a "day to be blotted out."

Olive Banks argued: "Henry Nevinson had no talent for domesticity and his temperament craved a life of adventure." Nevinson became the lover of Evelyn Sharp. In 1913 Nevinson wrote to Sidney Webb: "She (Sharp) has one of the most beautiful minds I know - always going full gallop, as you see from her eyes, but very often in regions beyond the moon, when it takes a few seconds to return. At times she is the very best speaker among the suffragettes."

On 4th August, 1914, England declared war on Germany. Two days later the NUWSS announced that it was suspending all political activity until the war was over. The leadership of the WSPU began negotiating with the British government. On the 10th August the government announced it was releasing all suffragettes from prison. In return, the WSPU agreed to end their militant activities and help the war effort.

Emmeline Pankhurst announced that all militants had to "fight for their country as they fought for the vote." After receiving a £2,000 grant from the government, the WSPU organised a demonstration in London. Members carried banners with slogans such as "We Demand the Right to Serve", "For Men Must Fight and Women Must work" and "Let None Be Kaiser's Cat's Paws". At the meeting, attended by 30,000 people, Emmeline Pankhurst called on trade unions to let women work in those industries traditionally dominated by men.

Nevinson was appalled by the behaviour of the WSPU and instead agreed with the Women's Freedom League approach to the conflict. This included the campaign of the Women's Peace Crusade for a negotiated peace. Her son, the artist, Christopher Nevinson, was a pacifist and refused to become involved in combat duties, and volunteered instead to work for the Red Cross on the Western Front.

After the passing of the Qualification of Women Act Nevinson continued to campaign for women's rights. In 1923 the Women's Freedom League published The Legal Wrongs of Women. This was followed by two volumes of autobiography, Fragments of Life, Tales and Sketches (1922) and Life's Fitful Fever (1926). She was asked twice to stand for the House of Commons, but each time she refused.

Margaret and Henry still lived together. They used to eat separately except for Sundays. According to her biographer, Angela V. John: "Her final years were lonely ones, plagued by depression." Christopher Nevinson described their home "a cheerless uninhabited house". Henry wrote: "Children are a quiverful of arrows that pierce the parents' hearts."

In 1928 Margaret Nevinson told friends that she wanted to go into a nursing home "and have done with it". She tried to drown herself in the bath. Henry Nevinson wrote to Elizabeth Robins about her health: "At present I am in great tribulation, for Mrs. Nevinson's mind is rapidly failing, and I am perplexed what is best for her. To send her to a mental home among strangers seems to me cruel, but all are urging it, partly in hopes of reducing the great expense. I am so much opposed to it that I should far rather go on spending my small savings in the hope that she may end quietly here." Margaret Nevinson died of kidney failure at her Hampstead home, 4 Downside Crescent, on 8th June 1932.

On this day in 1885 Alice Paul was born into a Quaker family in Moorestown, New Jersey. Educated in the United States at Swarthmore College and Pennsylvania University, where she earned a master's degree in sociology. In 1907 Paul she moved to England where she was a Ph.D. student at the School of Economics and Political Science (LSE).

In 1908 Paul heard Christabel Pankhurst make a speech at the University of Birmingham. Inspired by what she heard, Paul joined the Women's Social and Political Union (WSPU) and her activities resulted in her being arrested and imprisoned three times. Like other suffragettes she went on hunger strike and was forced-fed.

After one arrest Paul met Lucy Burns, another American who had joined the WSPU while studying in England. Paul returned home in 1910 where she became involved in the struggle for women's suffrage in the United States.

In 1913 Alice Paul joined with Lucy Burns to form the Congressional Union for Women Suffrage (CUWS) and attempted to introduce the militant methods used by the Women's Social and Political Union in Britain. This included organizing huge demonstrations and the daily picketing of the White House.

After the United States joined the First World War, Paul was continually assaulted by patriotic male bystanders, while picketing outside the White House. In October, 1917, Paul was arrested and imprisoned for seven months.

Paul went on hunger strike and was released from prison. In January, 1918, Woodrow Wilson announced that women's suffrage was urgently needed as a "war measure". However, it was not until 1920 that the 19th Amendment secured the vote for women.

Paul continued to campaign for women's rights and in 1938 founded the World Party for Equal Rights for Women (also known as the World Women's Party). Paul also successfully lobbied for references to sex equality in the preamble to the United Nations Charter and in the 1964 Civil Rights Act.

Alice Paul died in Moorestown, New Jersey, on 9th July, in 1977.

On this day in 1896 secret agent William Stephenson, the son of William Hunter Stanger, an immigrant from Orkney who worked in a flour mill at Point Douglas, and his wife, Sarah Johnston, was born in Winnipeg, Canada on 11th January, 1896. His father died in 1901 his mother was left to bring up three young children. Bina Ingimundson told Bill Macdonald: "When her husband died, she had three children. There was no way she could support them. So she gave Bill to my aunt." Bina's aunt was Kristin Stephenson, the wife of Vigfus Stephenson, a labourer in a lumber yard. In recognition of this he took the name of his adopted parents. Stephenson was educated at Argyle Elementary School. One of his teachers, Jean Moffat, later recalled: "William Stephenson was a bookworm... who loved boxing. A wee fellow, but a real one for a fight. Of course, you see, he was the man of the house since the time he was a toddler."

After leaving school he worked in a lumber yard, and then delivered telegrams for Great North West Telegraph. In December 1913 he became involved in a famous murder case. John Krafchenko, a man with a long criminal record, shot dead Henry Medley Arnold, the manager of the Bank of Montreal in Plum Coulee, Manitoba. A watch found in the getaway car was traced through a pawnshop's records to being owned by Krafchenko. The local newspaper reported that Krafchenko "has a genius for robberies requiring desperate action". Another report claimed that Krafchenko was "one of the most cultured men imaginable". Krafchenko wen into hiding in a house in Winnipeg. It was while delivering telegrams Stephenson spotted the wanted man and reported it to the police.

Stephenson followed the trial of Krafchenko with great interest and was fascinated to discover that he confessed to having a fountain pen filled with nitroglycerine. He intended to use it as a bomb in order to avoid capture. During the trial he escaped from prison but was caught soon after. Five other men were taken into custody for aiding his escape, including his attorney, a legal clerk, a former building trade official and a prison guard. The local newspaper reported that his accomplices were "under the spell of his fascinating personality". Krafchenko was executed in 1914.

Stephenson was determined to get involved in the First World War. On 12th January 1916, he enlisted in the Winnipeg Light Infantry. According to the doctor who examined him he had brown eyes, dark hair, a dark complexion, five foot two inches tall with a 32-inch expanded girth. He was considered to be too small to be a soldier and the medical officer wrote "passed as bugler" on his papers. Stephenson received basic training in Winnipeg before being sent by boat to Britain, arriving on 6th July, 1916.

Stephenson arrived on the Western Front later that month. He was wounded during a gas attack less than a week later and was returned to England to convalesce at Shorncliffe. It took him several months to recover his fitness. Instead of being sent back to France he was sent on courses in the theory of flight, internal combustion engines, communications and navigation. In April 1917 he was promoted to the rank of sergeant and joined the Cadet Wing of the Royal Flying Corps for training as a pilot.

In February, 1918, Stephenson was sent to France where he joined the 73 Squadron. Soon after arriving he met Gene Tunney. Both men were keen on boxing and Stephenson won the featherweight championship of the Inter Allied Games at Amiens. Tunney said later: "Everybody admired him. He was quick as a dash of lightning. He was a fast, clever featherweight... he was a fearless and quick thinker."

Stephenson's Sopwith Camel was attacked by two enemy aircraft in March 1918 and was severely damaged. He landed out of control and was nearly killed. According to H. Montgomery Hyde, the author of The Quiet Canadian (1962): "He immediately got into another machine and the first thing we knew there was a report that he shot down two Germans." The following month he was awarded the Military Cross. It was later recorded: "When flying low and observing an open staff car on a road, he attacked it with such success that later it was seen lying in the ditch upside down. During the same flight, he caused a stampede amongst some enemy transport horses on a road. Previous to this, he had destroyed a hostile scout and a two-seater plane. His work has been of the highest order and he has shown the greatest courage and energy in engaging every kind of target."

There has been some dispute over exactly how many enemy aircraft were shot down by William Stephenson. Cross and Cockade International, a First World War aviation society, Stephenson shot down a total of 12 aircraft. However, a French newspaper reported in 1918 that he had shot down eighteen aircraft and two kite balloons. His achievements were acknowledged when he was awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross in 1918.

On 28th July 1918, Stephenson was reported missing. The French newspaper Avion commented: "It appears that on the afternoon of July 28th, Captain Stephenson, decided to make a lone patrol of the line. Regular Scout patrols had been canceled for the day owing to stormy weather. About four miles within the Bosche Lines... one of our reconnaissance machines was being attacked by seven Fokker Biplanes which had been hiding in the dense clouds a few hundred metres above. According to American balloon observers, a British machine of the pattern Stephenson flew suddenly dived out of the clouds and without hesitation attacked the leader of the enemy formation, shooting him down in flames. There followed a terrific battle in which the daring captain made excellent strategic use of the clouds and succeeded in shooting down another German machine, while a third went spinning to the ground out of control." The report then went on to explain that Stephenson was shot down. "France has good reason to cherish the memory of this brilliant young Canadian pilot and to pray that he descended alive."

Stephenson's friend, Tommy Drew-Brook, explained what had happened: "The unfortunate French observer saw this machine out of the corner of his eye, spun his gun and fired a burst into Bill, which killed his engine and put one bullet through his leg. He landed just in front of the German front line, crawled out of his machine, and headed for our lines, but unfortunately a German gunner hit him again in the same leg and that stopped him and resulted in him being captured."

While in the prison-camp, Stephenson stole a German tin opener. Stephenson was impressed with performance of the tin opener and told Drew-Brook that he planned to escape from the camp as soon as possible, and he was going to take the can opener with him, and patent it in every country in the world. He did manage to escape and by 1919 he was back in Winnipeg selling can openers. Drew-Brook later recalled: "He took the can opener with him, and I think he did patent it and I believe was successful in making considerable money out of it."

In January 1921 Stephenson formed a business partnership with Charles Wilfred Russell "to carry on the business of Manufacturers Agents, Exporters and Importers of hardware goods, cutlery, auto accessories, groceries, timber, and goods, wares and merchandise of every description." The main purpose was to sell can openers but in recession hit Canada this was not an easy task and in August, 1922, the partners filed for bankruptcy. Owing a large amount of money Stephenson fled to England. Joan Morrison recalled: "He left in a rather bad odour. He got money from many people in the Icelandic community, and didn't pay it back. Then he left town in the dark of the night."

Stephenson started up a new company at 28 South Audley Street. He joined up with T. Thorne Baker, who was carrying out research into photo-telegraphy. Both men began work in developing a machine that could send photos over telephone lines. Stephenson later told Harford Montgomery Hyde that they developed a "light sensitive device" that increased the rate of transmission. Stephenson realized that if the process was sped up even further, moving pictures could be transmitted. In other words, televison sets.

On 28th August 1923, The Manitoba Free Press reported: "Due partly to his efforts and a tremendous advertising campaign, broadcasting was established in England on a highly efficient and comprehensive scale within a few short months and his companies were the first in England to produce a complete range of broadcasting equipment suitable for public use." The Daily Mail, who had made use of this technology, described Stephenson as a "brilliant scientist" and credited him with "a leading role in the revolutionary transmission of wireless photography". According to a newspaper in South Carolina, Stephenson predicting "moving pictures... may soon be possible to see... at one's home."

In 1923 Stephenson became the managing director of the General Radio Company Limited and the Cox Cavendish Electrical Company. The companies manufactured radios at Twyford Abbey Works on Acton Lane in Harlesden and had showrooms at 105 Great Portland Street for their wireless, X-ray and electro-medical supplies. Another newspaper claimed that "Stephenson... devoted himself to solving the problem of the wireless transmission of photographs and television... He has gone a long way toward the solution of these problems and has been successful in transmitting photographs by wireless suitable for newspaper reproduction."

Stephenson met Mary Simmons on board a boat returning from a business trip to New York City. Mary was the daughter of William H. Simmons, of Springfield, Tennessee. The couple married on 22nd July 1924 at Emperor's Gate Presbyterian Church, South Kensington. None of Stephenson's parents were present at the wedding. The New York Times reported on 31st August that Mary Simmons had married "Captain William Samuel Stephenson, inventor of a device to send photographs by radio." Marion de Chastelain knew the Stephensons and later recalled: "Mary was just the right size for him because Bill was quite short and she was even shorter. I felt tall tall when I was next to her."

Richard Deacon, the author of Spyclopaedia: The Comprehensive Handbook of Espionage (1987), has pointed out: "After the war he became a pioneer in broadcasting and especially in the radio transmission of photographs. By the 1930s he had become an important man involved in broadcasting developments in Canada, in a film company in London, the manufacture of plastics and the steel industry." In 1934 Stephenson hired Flight Lieutenant H. M. Schofield to fly a plane produced by his General Aircraft Limited to win the King's Cup air race with an average speed of 134.16 miles an hour in poor weather conditions.

Stephenson received the financial backing of Charles Jocelyn Hambro. This enabled him to take control of Alpha Cement, which was one of the largest cement companies in Britain. He also established Sound City films and built Shepperton Studios. It eventually became the largest film studios outside Hollywood. In 1936 Stephenson joined the board of Pressed Steel Company, which made 90 percent of Britain's car bodies. Stephenson told Thomas F. Troy that he purchased it from Edward G. Budd Company of Philadelphia for $13 million.

Roald Dahl considered Stephenson to have a brilliant mind: "There's no question about that, I mean the fact he became a millionaire about the same time as Lord Beaverbrook and at about the same age, 27 or 28. Came over here and took over Pressed Steel at that age... and it was not so easy to become a millionaire as it is today. He became rich as soon as he wanted to, more or less."

Gill Bennett has claimed that he "built up a highly successful career as a businessman, becoming a millionaire through enterprises such as the Pressed Steel Company, which apparently made ninety percent of car bodies for British automobile manufacturerers." While on a business trip in Nazi Germany he discovered that practically the whole of German steel production had been turned over to armament manufacture. Stephenson decided to create his own private clandestine industrial intelligence organisation. He then offered his services to the British government. He was put into contact with MI6 which was initially not very enthusiastic. Undeterred, Stephenson set up the International Mining Trust (IMT) in Stockholm, "under cover of which he aimed to develop contacts into Germany and elsewhere to provide industrial and other intelligence."

According to Charles Howard Ellis, a British intelligence officer, Stephenson began "providing a great deal of information on German rearmament" to Winston Churchill. He went on to argue that although Churchill was not in office, "He was playing quite an important role in providing background information. There were members of the House of Commons who were much more concerned about what was happening than the administration seemed to be at that time."

Roald Dahl has argued that Stephenson was a close friend of Lord Beaverbrook during this period: "He did not know Churchill personally then... with his absolute cleverness, he spotted Churchill as a future leader.... He could have sent them to Halifax or Chamberlain. But they were both idiots, and he wouldn't have got anywhere... I think Max Beaverbrook advised him to do it, too, because they were both Canadians. He was a close friend, a really genuinely close friend of Beaverbrook."

The author of A Man Called Intrepid (1976) was told by Stephenson that he met with German military and aviation officials as early as 1934. At these meetings he is said to have learned more about Nazi doctrine and about the strategy of Blitzkreig. He was told, "the real secret is speed - speed of attack, through speed of communications". Stephenson passed this information on to Charles Vane-Tempest-Stewart, the 7th Marquess of Londonderry, who was Secretary of State for Air, under Ramsay MacDonald. The minister failed to take action, as he was sympathetic to the Adolf Hitler regime. He told Joachim von Ribbentrop in February 1936: "As I told you, I have no great affection for the Jews. It is possible to trace their participation in most of those international disturbances which have created so much havoc in different countries."

Stephenson eventually got this information to the British government and the new prime minister, Stanley Baldwin, moved the Marquess of Londonderry to leader of the House of Lords. A member of British Intelligence, Frederick William Winterbotham, and another Nazi sympathiser, wrote in his book, The Nazi Connection (1978): "Poor Lord Londonderry had been Baldwin's scapegoat. A most delightful man, I'd always felt that he was far too sensitive to be in the hurly-burly of politics in the thirties."

Bill Macdonald, the author of The True Intrepid: Sir William Stephenson and the Unknown Agents (2001) has suggested that this information was passed to Desmond Morton, the head of the Industrial Intelligence Centre, who reported to Churchill. Richard Deacon has pointed out: "Only one man was willing to give him a ready ear and find out more - Winston Churchill. From then until the outbreak of war Stephenson became one of a small, unofficial team who supplied Churchill with intelligence on Germany." The author of Churchill's Man of Mystery (2009) doubts the truth of this story: "Although claims that he secretly furnished details of German rearmament to Churchill during the interwar period seem dubious, it is true that he built up an international network of contacts and informants concerned principally with obtaining secret industrial information to enable financial houses to judge the advisability of pursuing business propositions."

In 1937 Stephenson reported on Reinhard Heydrich: "The most sophisticated apparatus for conveying top-secret orders was at the service of Nazi propaganda and terror. Heydrich had made a study of the Russian OGPU, the Soviet secret security service. He then engineered the Red Army purges carried out by Stalin. The Russian dictator believed his own armed forces were infiltrated by German agents as a consequence of a secret treaty by which the two countries helped each other rearm. Secrecy bred suspicion, which bred more secrecy, until the Soviet Union was so paranoid it became vulnerable to every hint of conspiracy."

According to Anthony Cave Brown, the author of The Secret Life of Sir Stewart Graham Menzies (1987), Stephenson came up with a plan in 1938 to assassinate Adolf Hitler with a high-powered sporting rifle at a Nazi rally. He suggested arming a "young English crack-shot with high powered telescopic sighted rifle". However, the plan was vetoed by Britain's foreign secretary, Lord Halifax, the leading exponent of appeasement. Instead, Neville Chamberlain, decided to negotiate with Hitler and he signed the Munich Agreement in September 1938.

Stephenson eventually established the British Industrial Secret Service (BISS) and offered it to the British government. Keith Jeffery, the author of MI6: The History of the Secret Intelligence Service: 1909-1949 (2010), has seen evidence of Stephenson working with the government: "Closer links were established after Dick Ellis began developing the 22000 network, and up to the outbreak of the war the IMT proved quite useful in providing information on German armament potential."

Ralph Glyn, the member of the House of Commons for Abingdon, arranged for Stephenson to meet leading figures at the Foreign Office. The meeting took place on 12th July, 1939. The official noted: "He is a Canadian with a quiet manner, and evidently knows a great deal about Continental affairs and industrial matters. During a short discussion on the oil and non-ferrous metal questions he showed that he possesses a thorough grasp of the situation." Desmond Morton described his information as invaluable and by September 1939, agreement was reached for BISS (now known as Industrial Secret Intelligence - ISI) to pass information to the Secret Intelligence Service.

Winston Churchill became prime minister in May 1940. He realised straight away that it would be vitally important to enlist the United States as Britain's ally. He sent Stephenson to the United States to make certain arrangements on intelligence matters. Stephenson's main contact was Gene Tunney, a friend from the First World War, who had been World Heavyweight Champion (1926-1928) and was a close friend of J. Edgar Hoover, the head of the FBI. Tunney later recalled: "Quite to my surprise I received a confidential letter that was from Billy Stephenson, and he asked me to try and arrange for him to see J. Edgar Hoover... I found out that his mission was so important that the Ambassador from England could not be in on it, and no one in official government... It was my understanding that the thing went off extremely well." Stephenson was also a friend of Ernest Cuneo. He worked for President Franklin D. Roosevelt and according to Stephenson was the leader of "Franklin's brain trust". Cuneo met with Roosevelt and reported back that the president wanted "the closest possible marriage between the FBI and British Intelligence."

On his return to London, Stephenson reported back to Churchill. After hearing what he had to say, Churchill told Stephenson: "You know what you must do at once. We have discussed it most fully, and there is a complete fusion of minds between us. You are to be my personal representative in the United States. I will ensure that you have the full support of all the resources at my command. I know that you will have success, and the good Lord will guide your efforts as He will ours." Charles Howard Ellis said that he selected Stephenson because: "Firstly, he was Canadian. Secondly, he had very good American connections... he had a sort of fox terrier character, and if he undertook something, he would carry it through."

Churchill now instructed Stewart Menzies, head of MI6, to appoint Stephenson as the head of the British Security Coordination (BSC). Menzies told Gladwyn Jebb on 3rd June, 1940: "I have appointed Mr W.S. Stephenson to take charge of my organisation in the USA and Mexico. As I have explained to you, he has a good contact with an official (J. Edgar Hoover) who sees the President daily. I believe this may prove of great value to the Foreign Office in the future outside and beyond the matters on which that official will give assistance to Stephenson. Stephenson leaves this week. Officially he will go as Principal Passport Control Officer for the USA."

As William Boyd has pointed out: "The phrase (British Security Coordination) is bland, almost defiantly ordinary, depicting perhaps some sub-committee of a minor department in a lowly Whitehall ministry. In fact BSC, as it was generally known, represented one of the largest covert operations in British spying history... With the US alongside Britain, Hitler would be defeated - eventually. Without the US (Russia was neutral at the time), the future looked unbearably bleak... polls in the US still showed that 80% of Americans were against joining the war in Europe. Anglophobia was widespread and the US Congress was violently opposed to any form of intervention." An office was opened in the Rockefeller Centre in Manhattan with the agreement of President Franklin D. Roosevelt and J. Edgar Hoover of the FBI.

Bill Ross Smith, who worked for British Security Coordination in New York City, has argued: "Stephenson was exactly the right man, because he had all these terrific contacts and had this tremendous flair of influencing people, in an incredibly quiet way. If he could walk into this room now, he could sit down in that chair and, without saying a word, dominate this room. I tell you he was absolutely, bloody well a genius... He was no James Bond because he didn't go around killing people with his bare hands, or even with a gun. He dealt strictly with his brain and personality."

Winston Churchill had a serious problem. Joseph P. Kennedy was the United States Ambassador to Britain. He soon came to the conclusion that the island was a lost cause and he considered aid to Britain fruitless. Kennedy, an isolationist, consistently warned Roosevelt "against holding the bag in a war in which the Allies expect to be beaten." Neville Chamberlain wrote in his diary in July 1940: "Saw Joe Kennedy who says everyone in the USA thinks we shall be beaten before the end of the month." Averell Harriman later explained the thinking of Kennedy and other isolationists: "After World War I, there was a surge of isolationism, a feeling there was no reason for getting involved in another war... We made a mistake and there were a lot of debts owed by European countries. The country went isolationist.

In July, 1940, Henry Luce, C. D. Jackson, Freda Kirchwey, Raymond Gram Swing, Robert Sherwood, John Gunther and Leonard Lyons, Ernest Angell and Carl Joachim Friedrich established the Council for Democracy in July, 1940. According to Kai Bird the organization "became an effective and highly visible counterweight to the isolation rhetoric" to America First Committee led by Charles Lindbergh and Robert E. Wood: "With financial support from Douglas and Luce, Jackson, a consummate propagandist, soon had a media operation going which was placing anti-Hitler editorials and articles in eleven hundred newspapers a week around the country." The isolationist Chicago Tribune accused the Council for Democracy of being under the control of foreigners: "The sponsors of the so-called Council for Democracy... are attempting to force this country into a military adventure on the side of England."

According to The Secret History of British Intelligence in the Americas, 1940-45, a secret report written by leading operatives of the British Security Coordination (Roald Dahl, H. Montgomery Hyde, Giles Playfair, Gilbert Highet and Tom Hill), Stephenson played an important role in the formation of the Council for Democracy: "William Stephenson decided to take action on his own initiative. He instructed the recently created SOE Division to declare a covert war against the mass of American groups which were organized throughout the country to spread isolationism and anti-British feeling. In the BSC office plans were drawn up and agents were instructed to put them into effect. It was agreed to seek out all existing pro-British interventionist organizations, to subsidize them where necessary and to assist them in every way possible. It was counter-propaganda in the strictest sense of the word. After many rapid conferences the agents went out into the field and began their work. Soon they were taking part in the activities of a great number of interventionist organizations, and were giving to many of them which had begun to flag and to lose interest in their purpose, new vitality and a new lease of life. The following is a list of some of the larger ones... The League of Human Rights, Freedom and Democracy... The American Labor Committee to Aid British Labor... The Ring of Freedom, an association led by the publicist Dorothy Thompson, the Council for Democracy; the American Defenders of Freedom, and other such societies were formed and supported to hold anti-isolationist meetings which branded all isolationists as Nazi-lovers."

Stephenson knew that with leading officials supporting isolationism he had to overcome these barriers. His main ally in this was another friend, William Donovan, who he had met in the First World War. "The procurement of certain supplies for Britain was high on my priority list and it was the burning urgency of this requirement that made me instinctively concentrate on the single individual who could help me. I turned to Bill Donovan." Donovan arranged meetings with Henry Stimson (Secretary of War), Cordell Hull (Secretary of State) and Frank Knox (Secretary of the Navy). The main topic was Britain's lack of destroyers and the possibility of finding a formula for transfer of fifty "over-age" destroyers to the Royal Navy without a legal breach of U.S. neutrality legislation.

It was decided to send Donovan to Britain on a fact-finding mission. He left on 14th July, 1940. When he heard the news, Joseph P. Kennedy complained: "Our staff, I think is getting all the information that possibility can be gathered, and to send a new man here at this time is to me the height of nonsense and a definite blow to good organization." He added that the trip would "simply result in causing confusion and misunderstanding on the part of the British". Andrew Lycett has argued: "Nothing was held back from the big American. British planners had decided to take him completely into their confidence and share their most prized military secrets in the hope that he would return home even more convinced of their resourcefulness and determination to win the war."

William Donovan arrived back in the United States in early August, 1940. In his report to President Franklin D. Roosevelt he argued: "(1) That the British would fight to the last ditch. (2) They could not hope to hold to hold the last ditch unless they got supplies at least from America. (3) That supplies were of no avail unless they were delivered to the fighting front - in short, that protecting the lines of communication was a sine qua non. (4) That Fifth Column activity was an important factor." Donovan also urged that the government should sack Ambassador Joseph Kennedy, who was predicting a German victory. Donovan also wrote a series of articles arguing that Nazi Germany posed a serious threat to the United States.

On 22nd August, Stephenson reported to London that the destroyer deal was agreed upon. The agreement for transferring 50 aging American destroyers, in return for the rights to air and naval basis in Bermuda, Newfoundland, the Caribbean and British Guiana, was announced 3rd September, 1940. The bases were leased for 99 years and the destroyers were of great value as convey escorts. Lord Louis Mountbatten, the British Chief of Combined Operations, commented: "We were told that the man primarily responsible for the loan of the 50 American destroyers to the Royal Navy at a critical moment was Bill Stephenson; that he had managed to persuade the president that this was in the ultimate interests of America themselves and various other loans of that sort were arranged. These destroyers were very important to us...although they were only old destroyers, the main thing was to have combat ships that could actually guard against and attack U-boats."

Stephenson was very concerned with the growth of the American First Committee. by the spring of 1941, the British Security Coordination (BSC) estimated that there were 700 chapters and nearly a million members of isolationist groups. Leading isolationists were monitored, targeted and harassed. When Gerald Nye spoke in Boston in September 1941, thousands of handbills were handed out attacking him as an appeaser and Nazi lover. Following a speech by Hamilton Stuyvesan Fish, a member of a group set-up by the BSC, the Fight for Freedom, delivered him a card which said, "Der Fuhrer thanks you for your loyalty" and photographs were taken.

A BSC agent approached Donald Chase Downes and told him that he was working under the direct orders of Winston Churchill. "Our primary directive from Churchill is that American participation in the war is the most important single objective for Britain. It is the only way, he feels, to victory over Nazism." Downes agreed to work for the BSC in spying on the American First Committee. He was also instructed to find information on German consulates in Boston and Cleveland and the Italian consulate in the capital. He later recalled in his autobiography, The Scarlett Thread (1953) that he received assistance in his work from the Jewish Anti-Defamation League, Congress for Industrial Organisation and U.S. army counter-intelligence. Bill Macdonald, the author of The True Intrepid: Sir William Stephenson and the Unknown Agents (2001), has pointed out: "Downes eventually discovered there was Nazi activity in New York, Washington, Chicago, San Francisco, Cleveland and Boston. In some cases they traced actual transfers of money from the Nazis to the America Firsters."

One of his earliest contacts was Robert E. Sherwood. In his book, Roosevelt and Hopkins: An Intimate History (1948) he argued: "There was established by Roosevelt's order and despite State Department qualms, effectively close cooperation between J. Edgar Hoover and British Security Services under the direction of a quiet Canadian, William Stephenson."

Charles Howard Ellis was sent to New York City to work alongside William Stephenson as assistant-director. Together they recruited several businessmen, journalists, academics and writers into the British Security Coordination. This included Roald Dahl, H. Montgomery Hyde, Ian Fleming, Ivar Bryce, Charles Howard Ellis, Noël Coward, David Ogilvy, Paul Denn, Eric Maschwitz, Cedric Belfrage, Giles Playfair, Benn Levy, Sydney Morrell and Gilbert Highet. The CIA historian, Thomas F. Troy has argued: "BSC was not just an extension of SIS, but was in fact a service which integrated SIS, SOE, Censorship, Codes and Ciphers, Security, Communications - in fact nine secret distinct organizations. But in the Western Hemisphere Stephenson ran them all."

Assistant Secretary of State Adolf Berle reported to Sumner Welles on 31st March, 1941, that "the head of the field service appears to be Mr. William S. Stephenson... in charge of providing protection for British ships, supplies etc. But in fact a full size secret police and intelligence service is rapidly evolving... with district officers at Boston, New York City, Philadelphia, Baltimore, Charleston, New Orleans, Houston, San Francisco, Portland and probably Seattle."

Over the next few years Stephenson worked closely with William Donovan, the chief of the Office of Strategic Service (OSS). Gill Bennett has argued: "Each is a figure about whom much myth has been woven, by themselves and others, and the full extent of their activities and contacts retains an element of mystery. Both were influential: Stephenson as head of British Security Coordination (BSC), the organisation he created in New York at Menzies's request and Donovan, working with Stephenson as intermediary between Roosevelt and Churchill, persuading the former to supply clandestine military supplies to the UK before the USA entered the war, and from June 1941 head of the COI and thus one of the architects of the US Intelligence establishment."

Grace Garner, Stephenson's secretary, claimed he recruited several journalists including Sydney Morrell from the Daily Express and Doris Sheridan, from the Daily Mirror. "This was propaganda, or at least putting forward the British case. Sheridan liaised with the Arab sections in New York, keeping in touch with foreign nationals. The English playwright Eric Maschwitz was recruited to write propaganda and scripts. University professor Bill Deaken worked for the office, as well as the philosopher A. J. Ayer." Cedric Belfrage and Gilbert Highet were also recruited by Stephenson: "Belfrage was brought in as one of the propaganda people... he was a known communist... Gilbert Highet was in propaganda with Belfrage." John D. Bernal, used to call in the office. Garner described as a "dead ringer" for Harpo Marx. "You could have walked him straight onto the set. Wild. He had a funny hat on, and this saggy, greeny old coat, bulging with documents."

Grace Garner enjoyed working with Stephenson: "He had very dark, piercing eyes and the uncanny stillness of the man. When he walked he was very quiet and still... He had that quality of blending into a crowd. He certainly took in things in an instant, and he got to the centre of a thing. He would not put up with long documents... He wouldn't stand for gobbledygook... His English was flawless, his style was terse, tense and to the point... He was a very small in stature, neat man and very neatly put together, doesn't move his hands or do anything like that. A very still person.. He walked like a black panther... He moved fast, but it was silent.... He didn't like tall people. He said their brains were too far from their feet."

One of Stephenson's agents was Ivar Bryce. According to Thomas E. Mahl, the author of Desperate Deception: British Covert Operations in the United States, 1939-44 (1998): "Bryce worked in the Latin American affairs section of the BSC, which was run by Dickie Coit (known in the office as Coitis Interruptus). Because there was little evidence of the German plot to take over Latin America, Ivar found it difficult to excite Americans about the threat."

Nicholas J. Cull, the author of Selling War: The British Propaganda Campaign Against American Neutrality (1996), has argued: "During the summer of 1941, he (Bryce) became eager to awaken the United States to the Nazi threat in South America." It was especially important for the British Security Coordination to undermine the propaganda of the American First Committee. Bryce recalls in his autobiography, You Only Live Once (1975): "Sketching out trial maps of the possible changes, on my blotter, I came up with one showing the probable reallocation of territories that would appeal to Berlin. It was very convincing: the more I studied it the more sense it made... were a genuine German map of this kind to be discovered and publicised among... the American Firsters, what a commotion would be caused."

Stephenson, who once argued that "nothing deceives like a document", approved the idea and the project was handed over to Station M, the phony document factory in Toronto run by Eric Maschwitz, of the Special Operations Executive (SOE). It took them only 48 hours to produce "a map, slightly travel-stained with use, but on which the Reich's chief map makers... would be prepared to swear was made by them." Stephenson now arranged for the FBI to find the map during a raid on a German safe-house on the south coast of Cuba. J. Edgar Hoover handed the map over to William Donovan. His executive assistant, James R. Murphy, delivered the map to President Franklin D. Roosevelt. The historian, Thomas E. Mahl argues that "as a result of this document Congress dismantled the last of the neutrality legislation."

Nicholas J. Cull has argued that Roosevelt should not have realised it was a forgery. He points out that Adolf A. Berle, the Assistant Secretary of State for Latin American Affairs, had already warned Cordell Hull, the Secretary of State that "British intelligence has been very active in making things appear dangerous in South America. We have to be a little on our guard against false scares."

British Security Coordination (BSC) managed to record the conversations of Japanese special envoy Suburu Kurusu with others in the Japanese consulate in November 1941. Marion de Chastelain was the cipher clerk who transcribed these conversations. On 27th November, 1941, William Stephenson sent a telegram to the British government: "Japanese negotiations off. Expect action within two weeks." According to Roald Dahl, who worked for BSC: "Stephenson had tapes of them discussing the actual date of Pearl Harbor... and he swears that he gave the transcription to FDR. He swears that they knew therefore of the oncoming attack on Pearl Harbor and hadn't done anything about it."

Bill Macdonald, the author of The True Intrepid: Sir William Stephenson and the Unknown Agents (2001) has pointed out: "Although they were called British Security Coordination, the Stephenson people were very much a law unto themselves. They made many separate deals with other countries and distributed information amongst the three Western Allies. They controlled many of the secrets of the three countries, including ULTRA and MAGIC, and also had communication influence in the South Pacific and Asia. There were a number of British appointments at BSC, but essentially, Stephenson contacted his friends, put them to work, and had them find staff... The important work these people accomplished during the war has never been fully explored."

On 13th February, 1942, Adolph Berle received information from the FBI that a BSC agent, Dennis Paine, had been investigating him in order to "get the dirt" on him. Paine was expelled from the United States. Stephenson believed that Paine had been set-up as part of a FBI public relations exercise. He later recalled: Adolf Berle was slightly school-masterish for a very brief period due to misinformation, but could not have been more helpful when factual situation was clarified to him."

William Boyd has argued the BSC "became a huge secret agency of nationwide news manipulation and black propaganda. Pro-British and anti-German stories were planted in American newspapers and broadcast on American radio stations, and simultaneously a campaign of harassment and denigration was set in motion against those organisations perceived to be pro-Nazi or virulently isolationist".

Keith Jeffery, the author of MI6: The History of the Secret Intelligence Service: 1909-1949 (2011) has pointed out: "The New York organisation expanded well beyond pure intelligence matters, and eventually combined the North American functions not just of SIS, but of M15, SOE and the Security Executive (which existed to co-ordinate counter-espionage and counter-subversion work): intelligence, security, special operations and also propaganda. Agents were recruited to target enemy or enemy controlled businesses, and penetrate Axis (and neutral) diplomatic missions; representatives were posted to key points, such as Washington, New Orleans, Los Angeles, San Francisco and Seattle; American journalists, newspapers and news agencies were targeted with pro-British material; an ostensibly independent radio station (WURL), with an unsullied reputation for impartiality, was virtually taken over."

William Donovan, the chief of the Office of Strategic Service (OSS) has called the British Security Coordination (BSC) "the greatest integrated secret intelligence and operations organization that has ever existed anywhere". David Bruce, who was a member of the OSS has argued: "Had it not been for Stephenson's achievements it seems to me highly possible that the Second World War would have followed a different and perhaps fatal course."

At the end of the Second World War the files of British Security Coordination were packed onto semitrilers and transported to Camp X in Canada. Stephenson wanted to have some record of the activities of the agency, "To provide a record which would be available for reference should future need arise for secret activities and security measures for the kind it describes." He recruited Roald Dahl, H. Montgomery Hyde, Giles Playfair, Gilbert Highet and Tom Hill, to write the book. Stephenson told Dahl: "We don't dare to do it in the United States, we have to do it on British territory." Dahl commented: "He (Stephenson) pulled a lot over Hoover... He pulled a few things over the White House, too, now and again. I wrote a little bit but eventually I called Bill and told him that it's an historian's job... This famous history of the BSC through the war in New York was written by Tom Hill and a few other agents." Only twenty copies of the book were printed. Ten went into a safe in Montreal and ten went to Stephenson for distribution.

In September 1945, Stephenson was told about Igor Gouzenko, a Soviet Embassy cipher clerk who was also working for Soviet military intelligence, who wanted to defect. Gouzenko later wrote: "During my residence in Canada, I have seen how the Canadian people and their government, sincerely wishing to help the Soviet people sent supplies to the Soviet Union, collected money for the welfare of the Russian people, sacrificing the lives of their sons in the delivery of supplies across the ocean - and instead of gratitude for the help rendered, the Soviet government is developing espionage activity in Canada, preparing to deliver a stab in the back to Canada - all this without the knowledge of the Russian people."

Stephenson arranged for Gouzenko to be taken into protective custody. He was then transfered to Camp X, where he and his wife lived in guarded seculusion. Later two former BSC agents interviewed him. Gousenko's evidence led to the arrest of Klaus Fuchs and Alan Nunn May and 17 others in 1946. As Bill Macdonald has pointed out: "He (Gouzenko) is regarded as the most important defector of the era, and his revelations are often regarded as the beginning of the Cold War."

After the war Stephenson bought a house, Hillowton, on Jamaica overlooking Montego Bay. His close friends, Lord Beaverbrook, William Donovan, Ian Fleming, Ivar Bryce and Noël Coward, also purchased property on the island. Roald Dahl has argued that Stephenson was very close to Beaverbook during this period: "He was a close friend, a really genuinely close friend of Beaverbrook. I've been in Beaverbrrok's house in Jamaica with him and they were absolutely like that (crossing his fingers)... A couple of old Canadian millionaires who were both pretty ruthless." He also kept in close contact with Henry Luce, Hastings Ismay and Frederick Leathers. His friends recalled that he was drinking heavily. Marion de Chastelain commented that "he made the wickedest martini that was ever made". Coward refered to him often having "too many martinis".

In 1951 Stephenson sold Hillowton and moved to New York City. Soon afterwards he was appointed chairman of the Newfoundland and Labrador Corporation, by the Canadian province's first premier, Joey Smallwood. He helped attract new industries and investment but resigned in October 1952 because he thought the corporation should have a local head. Smallwood accepted his resignation with reluctance and regret: "You achieved a magnificent result in a very short space of time, and I and the Government and people of Newfoundland must ever be grateful to you."

Stephenson also set up the British-American-Canadian-Corporation (later called the World Commerce Corporation) with William Donovan. It was a secret service front company which specialized in trading goods with developing countries. William Torbitt has claimed that it was "originally designed to fill the void left by the break-up of the big German cartels which Stephenson himself had done much to destroy."

Most of the leading figures in the company were formerly in the British Security Coordination (BSC) and the Office of Strategic Service (OSS). The company used barter agreements and dollar guarantees to get around currency restrictions that slowed world trade. Tom Hill, who worked for the World Commerce Corporation later recalled: "The idea was to take advantage of the organization and international contacts that were set up during the war... The goal was to set up various companies, mostly in Central and South America."

Roald Dahl argues that the original idea came from David Ogilvy who argued that "we all needed jobs in civilian life." Dahl claims that Stephenson liked the idea and circulated copies of Ogilvy's paper to some of the wealthy people he worked with during the war and some of them put up capital. Other people involved in the organization included Lord Beaverbrook, Ian Fleming, Ivar Bryce, Henry Luce, Nelson Rockefeller, John McCloy, Edward Stettinius, Charles Hambro, Richard Mellon, Victor Sassoon, Roundell Palmer, Ralph Glyn, Frederick Leathers, William Rootes, Alexander Korda, Campbell Stewart (director of The Times) and Lester Armour. Another business associate during this period was William Formes-Sempill, who we now know was a Nazi spy during the Second World War. It has been suggested by Thomas F. Troy, a senior officer in the CIA, believed Stephenson continued to be involved in intelligence activities.

One of the successes of the World Commerce Corporation was to bring a cement industry to Jamaica. Stephenson became chairman of the board of the Caribbean Cement Company Limited. In a speech he gave to shareholders of 1961 the company declared a profit of over £600,000 and he said that since 1952 the total savings to the country as a result of domestic production were over £3 million.

In the 1960s Stephenson commissioned H. Montgomery Hyde, to write The Quiet Canadian (1962) a book about his work with the British Security Coordination. According to his biographer, David Hunt: "Its numerous invented stories, based on briefing from Stephenson, created a certain sensation but it still came short of Stephenson's inflated ideas; and as fresh revelations of British successes in the intelligence sphere continued to appear - for instance the Ultra secret - he clearly wished to claim credit for them." A classified CIA review said: "The publication of this study is shocking... Exactly what British intelligence was doing in the United States was closely held in Washington, and very little had hitherto been printed about it... One may suppose that Mr. Hyde's account... is relatively accurate, but the wisdom of placing it on the public record is extremely questionable."

Stephenson then commissioned William Stevenson (no relation of his), and provided him with a fund of fresh stories. A Man Called Intrepid was published in 1976. Hugh Trevor-Roper, a former intelligence officer, argued that the book was from "start to finish utterly worthless" and that Stephenson "was a fraud who fooled the world into believing he was a master spy". David A. Stafford supported this view: "The amazing exploits of our favourite spymaster turned out to contain large doses of fiction concocted in the forgetful mind of an old man."

David Hunt argues that the book "is almost entirely a work of fiction". A.J.P. Taylor, wrote in the New Statesman: "Nearly everything in the book is either exaggerated, distorted or already known." However, Bill Macdonald, the author of The True Intrepid: Sir William Stephenson and the Unknown Agents (2001), who has studied the life of Stephenson in great detail, admits that both books include factual mistakes, he played a very important role in British Intelligence during the Second World War.

William Stephenson and his wife moved to Bermuda. Their friend, Marion de Chastelain, commented: "Mary didn't particularly care for Bermuda... She loved New York and she had lots of friends.... she found Bermuda fairly boring... It must have been difficult for her, because Bill was not a man to socialize. You know, go to big parties." Soon afterwards Stephenson suffered a stroke. Roald Dahl went to see him and was shocked by the way his speech was affected. Dahl was told his survival was uncertain. One day Ernest Cuneo told him, "we need you to fight the Reds." Dahl claimed that he perked up after that.

Mary Stephenson died of cancer in 1977. Her full-time nurse, Elizabeth Baptiste and her son Rhys remained in Bermuda and looked after Stephenson. In 1983 Stephenson adopted Elizabeth as his daughter. Marion de Chastelain objected to an article in a magazine by David A. Stafford that suggested Stephenson was senile by this time: "He wasn't out of it at all. The impression of course could be due to his speech problem (after his stroke). Sometimes it was extremely good. And other times it wasn't... that would give the impression that he wasn't quite with it. You had to listen to what he said, not the way he said it."

Thomas F. Troy, a staff officer of the CIA, interviewed Stephenson for his book, Wild Bill and Intrepid: Donovan, Stephenson and the Origins of the CIA (1996): "Stephenson, then 73, showed the effects of a stroke: a cane, shuffling feet, a slightly closed left eye, a curled upper lip, slightly slurred speech, and the years had made him heavier than the lightweight of old. But he smiled readily, his handshake was firm, his eyes were bright, his voice was strong, and his mind was active. Proof of his relative well being? On that first visit we and his wartime deputy sat in undisturbed lively conversation for fully four hours."

William Stephenson died on 3rd January, 1989. He was buried in Bermuda in a secret ceremony at St. John's Church. He told his adopted daughter before he died: "I don't want people to know that I am dead until I am buried."

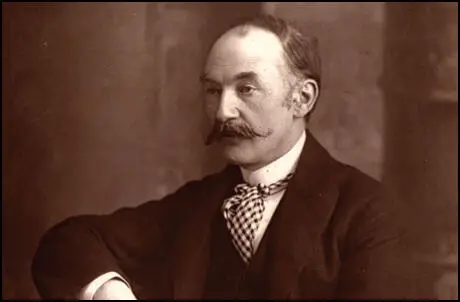

On this day in 1928 Thomas Hardy died aged 87. Hardy, the first of the four children of Thomas Hardy (1811–1892) and and his wife, Jemima (1813–1904), was born in Upper Bockhampton, near Dorchester, on 2nd June 1840. His father was a stonemason and jobbing builder.

According to his biographer, Michael Millgate: "As a sickly child, not confidently expected to survive into adulthood and kept mostly at home, Hardy gained an intimate knowledge of the surrounding countryside, the hard and sometimes violent lives of neighbouring rural families, and the songs, stories, superstitions, seasonal rituals, and day-to-day gossip of a still predominantly oral culture."

At eight Hardy went to the new national school in local school in Bockhampton. His mother was determined that he had a good education, and after a year arranged for him to study Latin, French and German at a nonconformist school in Dorchester. This involved a 3 miles walk, twice daily for several years.

At the age of 16 Hardy he was articled to John Hicks, an architect. During this period he became friends with Horace Moule, the socialist son of Horace Moule and evangelical vicar in Fordington. Moule was eight years older than Hardy. Moule has been described as "a charming and gentle man as well as a brilliant teacher". Moule also introduced him to socialism and to the radical ideas being expressed in the Saturday Review. Edited by John Douglas Cook, it attributed the majority of social evils to social inequality. Hardy became a great admirer of Percy Bysshe Shelley for his "genuineness, earnestness, and enthusiasms on behalf of the oppressed".

Once qualified, he moved to London and found work with a company that specialized in church architecture. In his spare-time he continued his education with visits to the theatre, opera and art galleries. It was at this time he began to write poetry, and although he submitted them to several magazines, they were all rejected.

In April 1862, Hardy left Dorchester for London, where he quickly found work as a draughtsman in the office of the successful architect, Arthur William Blomfield. Hardy was elected to the Architectural Association, and won in 1863 the silver medal of the Royal Institute of British Architects for an essay entitled On the Application of Coloured Bricks and Terra Cotta to Modern Architecture.

Hardy wanted to become a novelist. He received considerable support from his friend, Horace Moule, in achieving his objective. However, progress was slow. On 2nd June 1865, he wrote in his diary: "Feel as if I had lived a long time and done very little. Wondered what woman, if any, I should be thinking about in five years' time."

At about this time he became attached to his cousin, Tryphena Sparks, a student teacher from Puddletown, who was eleven years his junior. Tryphena was the daughter of Hardy's mother's sister. As Claire Tomalin, the author of Thomas Hardy: The Time Torn Man (2006) has pointed out: "Cousins could be a heaven sent answer to the need for emotional experiment and sexual adventure in Victorian England. They were accessible, flirtable with, almost sisters, part of the family, and, indeed, in many families marriages took place between cousins. So it is likely that Tom throughly enjoyed the company of all his girl cousins, flirted with them and made as much love to them as he could get away with when he had the chance... She was clever and pretty... and it seems that a warm cousinly affection developed as they got to know one another better."

In her book, Providence and Mr Hardy (1966), Lois Deacon argued that Tryphena gave birth to Hardy's illegitimate son. Robert Gittings, the author of The Young Thomas Hardy (2001) has argued that there is no real evidence for this claim: "What is certain is that Hardy became involved in some way with Tryphena... What passed between them... is difficult to say". Hardy's biographer, Michael Millgate, agrees with Gittings, and was unable to find any evidence of a child "capable of withstanding scholarly or even common-sensical scrutiny". However, he adds: "The two were often alone together, and it would not be extraordinary if they made love. But there was certainly no child, probably no formal engagement". The relationship came to an end when Hardy became engaged to Emma Gifford.

Ill-heath forced Thomas Hardy to return to his parent's home in the summer of 1867. After he recovered he decided against returning to London and resumed work with local architect, John Hicks. He also began work on his first novel, The Poor Man and the Lady. The story tells of the love and marriage of a young architect and the daughter of a large local landowner. According to Hardy: "The story was, in fact, a sweeping dramatic satire of the squirearchy and nobility, London society, the vulgarity of the middle class, modern Christianity, church restoration, and political and domestic morals in general, the author's views, in fact, being obviously those of a young man before and after him, the tendency of the writing being socialistic and revolutionary."

Hardy sent the manuscript to his friend, Horace Moule, who arranged for it to be read by publisher, Alexander Macmillan. He replied that although he liked some aspects of the novel he disliked was he considered to be an excessive attack on the upper classes.

Macmillan suggested that Hardy should approach Frederick Chapman of publishers Chapman and Hall, who were the current publishers of Charles Dickens. He agreed to publish The Poor Man and the Lady, but only if he paid the publishers the sum of £20 to cover any losses which the firm might incur by publishing the book.

Hardy then sent the manuscript to George Meredith. He replied that the book would be perceived as "socialistic" or even "revolutionary" and that as a result would not be well-received by the critics. Meredith went onto argue that this might prove to be handicap to Hardy's future career. He suggested that Hardy should either rewrite the story or write another novel with a different plot.

John Hicks died in 1868. Hardy now went to work for G.R. Crickmay, an architect in Weymouth. In March 1870 Hardy was sent to St. Juliot near Boscastle, by Crickmay, in order "to take a plan and particulars of a church I am about to rebuild there". While in the village Hardy met Emma Gifford, the daughter of a wealthy solicitor. She later recalled that Hardy had a beard and was wearing "a rather shabby great coat". Hardy fell in love with Emma and he returned to the village every few months. During this period Emma was described as having "a rosy, Rubenesque complexion, striking blue eyes and auburn hair with ringlets reaching down as far as her shoulders".

Robert Gittings, the author of The Young Thomas Hardy (2001) has argued: "Emma Lavinia Gifford certainly appears... as the spoilt child of a spoilt father. There is no doubt at all that wilfulness and lack of restraint gave her a dash and charm that captivated Hardy from the moment they met. He did not consider, any more than most men would have done, that a childish impulsiveness and inconsequential manner, charming at thirty, might grate on him when carried into middle age."

Later that year he sent Desperate Memories to Alexander Macmillan. He passed it to John Morley, the editor of The Fortnightly Review. Morley said the story was "ruined by the disgusting and absurd outrage which is the key to its mystery: the violation of a young lady at an evening party, and the subsequent birth of a child". Macmillan took Morley's advice and rejected the novel.

Hardy then approached the publishers, Tinsley Brothers. After he agreed to make changes they offered to publish the book if he paid them £75. Although he only had savings of £123 he agreed to the terms of the deal. Desperate Memories was published anonymously on 25th March 1871. It received some good reviews but was severely attacked in The Spectator, which condemned the author for "idle prying into the ways of wickedness". The book was not a commercial success and most of the 500 copies were remaindered and Hardy lost £15 in the venture.