On this day on 6th December

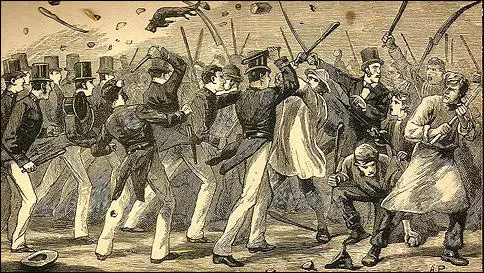

On this day in 1648 Colonel Thomas Pride purges the Long Parliament of MPs sympathetic to King Charles I. Pride was born near Glastonbury in about 1610. He worked as a drayman in London and on the outbreak of the Civil War joined the Parliamentary forces. He was a good soldier and eventually became a colonel in the New Model Army. Pride, who fought at Naseby, was given command of a brigade in Scotland.

In December 1648 Pride's troops expelled from the House of Commons that MPs who favoured a negotiated settlement with Charles I. After what became known as Pride's Purge, the remaining MPs formed the Rump Parliament, which remained in session until 1653. Pride was knighted and Oliver Cromwell nominated him to sit in Parliament. He was also given large estates and he purchased Nonsuch, a palace previously owned by Henry VIII. Sir Thomas Pride died in 1658.

On this day in 1815 George Binns, the son of a draper, was born in Sunderland. George's parents were Quakers and he was educated at Ackworth School in Yorkshire. After serving his apprenticeship at his father's shop he worked in a drapers in Wakefield.

In 1837 both of his parents died and George Binns returned to Sunderland to take over the family's draper shop. By this time Binns had developed radical political views and with the help of his friend, James Williams, he established a Mechanics' Institute where local people could read newspapers such as The Poor Man's Guardian, The Gauntlet and The Northern Star.

For a while the two men shared the role of librarian at the Mechanics' Institute but in October they set up business as Booksellers, Stationers and Newspaper Agents at 9 Bridge Street, Sunderland. The shop sold books and newspapers and also served as a meeting place for Radicals in the town. Binns and Williams formed the Sunderland Democratic Association and the men worked closely with other Chartist organizations in the North East of England.

George Binns said at a meeting in Sunderland: "Eighteen hundred years ago the simple and sublime doctrine of equality was preached and taught and acted upon, but that doctrine has long been lost sight of, and now we see nothing but unchristian selfishness. The tyrants might boast of numbers and energy. The tyrants might array their cruelty, but the people will oppose with bravery. We are bound together with no selfish tie, they might boast of their Wellingtons, but we have a God."

Binns was a supporter of William Lovett and the Moral Force Chartists. In April 1839 Binns wrote an angry letter to the Sunderland Herald after it suggested that he had made a speech in favour of Feargus O'Connor and the Physical Force Chartists. The Sunderland magistrates were unconvinced and on 22nd July 1839, Binns and Williams were arrested and charged with attending illegal meetings and publishing a seditious handbill.

At their trial in July, 1840, both men were found guilty of attending an illegal meeting and were sentenced to six months imprisonment in Durham Gaol. George Binns and James Williams were released in January 1841. Chartists in the North East met the men at the gates of the prison and after a public meeting in Durham the men marched back to Sunderland.

After his release from Durham Gaol, Binns returned to his drapery business. He continued to speak and work for universal suffrage and in 1841 was nominated as the Chartist parliamentary candidate for Sunderland. The Liberal candidate was Viscount Howick, the son of Earl Grey, the man responsible for the 1832 Reform Act. Afraid of splitting the vote of the reformers, Binns withdrew. Binns contributed to Viscount Howick's victory by announcing that the Tory candidate had offered him a £125 bribe to stand in the election.

George Binns's drapery business was not successful and in May 1842 he was arrested and sent to Durham Gaol after being able to pay his debts. After his release from prison Binns decided to emigrate to New Zealand. On 1st August, 1842 he sailed from Gravesend and arrived at Nelson, New Zealand, on 14th December, 1842. In New Zealand George Binns worked as an accountant (1844), clerk (1845), and baker (1846-47). George Binns died of consumption on 5th April, 1847.

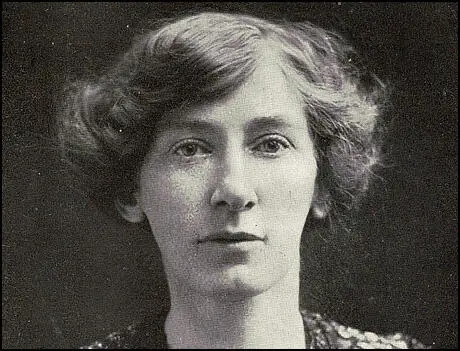

On this day in 1893, Sylvia Townsend Warner, the daughter of George Townsend Warner, a Harrow School history master, was born. Educated at home she worked in a munitions factory during the First World War.

Nancy Cunard introduced Warner to Mary Valentine Ackland and the two women lived together for the rest of their lives. Warner's first novel, Lolly Willowes, was published in 1926. This was followed by the novels Mr. Fortune's Maggot (1927) and The True Heart (1929).

Warner was the co-editor of the 10-volume Tudor Church Music (1923-29). Warner also wrote poetry and in 1933 published Whether A Dove or Seagull with Ackland. A regular contributor to New Yorker, Warner's poetry was praised by Alfred Edward Housman and William Butler Yeats and Louis Untermeyer compared her to Thomas Hardy.

Warner, was a leading member of the Communist Party of Great Britain in Dorset. She also gave support to the Spanish Medical Aid Committee, an organization that had been set-up by the Socialist Medical Association and other progressive groups. Other members included Leah Manning, Isabel Brown, George Jeger, Lord Faringdon, Arthur Greenwood, Tom Mann, Ben Tillett, Harry Pollitt, Hugh O'Donnell, Mary Redfern Davies and Isobel Brown. Soon afterwards Kenneth Sinclair Loutit was appointed Administrator of the Field Unit that was to be sent to Spain.

In September 1936 Warner and Mary Valentine Ackland went to Spain and provided help to the British Medical Aid Committee supporting the Republican Army. They were inspired by the revolutionary atmosphere they found in Barcelona. Warner wrote: "I don't think I have ever met so many congenial people in the whole of my life." However, the two women wrote a letter of complaint to Harry Pollitt about the "failure to adopt a satisfactory social attitude" by some members of the Communist Party of Great Britain.

However, Warner and Ackland went along with the Communist Party (PCE) repression of Worker's Party (POUM) in Barcelona. In The Daily Worker Ackland argued that the action had been justified because of "POUM's utopian non-authoritarian politics spelled certain death to the Republic pitched against the military strength of the Fascist powers."

On her return to Dorset Warner wrote an article for The Left Review about the way the Catholic Church oppressed the Spanish people. In a letter to her friend Elizabeth Wade she made the same point: "I have never seen churches so heavy and hulking and bullying, one can see at a glance that they have always been reactionary fortresses. I did not find a single person of any class who resented their being gutted, though we did find two domestic servants... who felt a certain uneasiness about it, as though God might pop out of those ruined choirs and grab them by the scruff. The not being able to read and write is the crux. A people naturally intellectual, and with a long standard of culture, have thrown off the taskmasters who enforced ignorance on them."

As Angela Jackson pointed out in British Women and the Spanish Civil War (2002): "They (Ackland and Warner) were involved in the founding of the local Left Book Club and Sylvia was secretary of the Dorset Peace Council. They were ardently committed to the cause of the Spanish Republic, campaigning and fund-raising in a whirl of breathless non-stop activity."

The following year the two women went to Madrid and Valencia as part of the British delegation to the Second Congress of the International Association of Writers for the Defence of Culture. Twenty-six countries participated in the conference. Warner wrote about it in an article published in Time and Tide in August 1937: "We learned to hear ourselves spoken of as los intelectuales without dreading words usually so dubious in good intent, without feeling the usual embarrassment and defiant shrinking."

Other novels by Warner include Summer Will Show (1936), After the Death of Don Juan (1938), The Corner That Held Them (1948) and The Flint Anchor (1954). During her career Warner published seven novels, ten volumes of short stories, five volumes of poetry and a biography of T. H. White.

Warner eventually left the Communist Party of Great Britain. The historian, Angela Jackson, argues: "Sylvia Townsend Warner allowed her membership of the Party to lapse during the 1950s. Along with other writers on the Left, she became a literary casualty of the Cold War." When she was asked why she had ceased to be active in politics: "We had fought, we had retreated, we were betrayed and now we were misrepresented." Sylvia Townsend Warner died in 1978.

On this day in 1902 the House of Commons passed a new Education Act. On 24th March 1902, Arthur Balfour presented to Parliament an Education Bill that attempted to overturn the 1870 Education Act that had been brought in by William Gladstone. It had been popular with radicals as they were elected by ratepayers in each district. This enabled nonconformists and socialists to obtain control over local schools.

The new legislation abolished all 2,568 school boards and handed over their duties to local borough or county councils. These new Local Education Authorities (LEAs) were given powers to establish new secondary and technical schools as well as developing the existing system of elementary schools. At the time more than half the elementary pupils in England and Wales. For the first time, as a result of this legislation, church schools were to receive public funds.

Nonconformists and supporters of the Liberal and Labour parties campaigned against the proposed act. David Lloyd George led the campaign in the House of Commons as he resented the idea that Nonconformists contributing to the upkeep of Anglican schools. It was also argued that school boards had introduced more progressive methods of education. "The school boards are to be destroyed because they stand for enlightenment and progress."

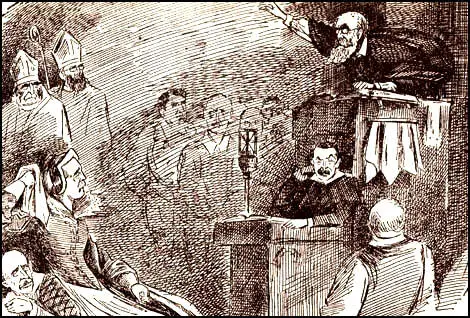

John Clifford became the leader of the campaign against the legislation. Clifford was opposed to Balfour's bill for three main reasons: (1) the rate aid was being used to support the teaching of religious views to which some rate-payers were opposed; (2) sectarian schools, supported by public funds, were not under public control; (3) teachers in sectarian schools were subject to religious tests.

John Clifford prepared a plan of "Passive Resistance". It was based on the strategy used by John Hampden against Ship Money in 1637 and one of the causes of the English Civil War. "Its tactics were to be those of the old Tithe War: refuse to pay the abhorrent education rate, submit rather to the forced sale of your goods and even of your house; if need be, go to jail!".

Clifford argued that people who disagreed with the proposed Education Act should refuse to pay at least that portion of the rate which was to be spent in or on church schools. The National Passive Resistance Committee was set-up with the motto "No Say. No Pay". However, within weeks the Anti-Martyrdom League was formed to pay the rates that the passive resisters withheld.

In July, 1902, a by-election at Leeds demonstrated what the education controversy was doing to party fortunes, when a Conservative Party majority of over 2,500 was turned into a Liberal majority of over 750. The following month a Baptist came near to capturing Sevenoaks from the Tories and in November, 1902, Orkney and Shetland fell to the Liberals. That month also saw a huge anti-Bill rally held in London, at Alexandra Palace.

Despite the opposition to the new Education Act, it was passed in December, 1902. John Clifford, wrote several pamphlets about the legislation that had a readership that ran into hundreds of thousands. Balfour accused him of being a victim of his own rhetoric: "Distortion and exaggeration are of its very essence. If he has to speak of our pending differences, acute no doubt, but not unprecedented, he must needs compare them to the great Civil War. If he has to describe a deputation of Nonconformist ministers presenting their case to the leader of the House of Commons, nothing less will serve him as a parallel than Luther's appearance before the Diet of Worms."

Rate refusals began in the spring of 1903. "What normally happened was that sufficient of their goods should be distrained and auctioned to defray the rate. It was usually arranged for a friend of the refuser should be on hand to buy back the goods." Over the next four years 170 men went to prison for refusing to pay their school taxes. This included 60 Primitive Methodists, 48 Baptists, 40 Congregationalists and 15 Wesleyan Methodists. John Clifford never went to prison but he appeared in court on 41 different occasions over the next ten years.

On this day in 1916 David Lloyd George ousts H. H. Asquith to become prime minister. At a meeting in Paris on 4th November, 1916, Lloyd George came to the conclusion that the present structure of command and direction of policy could not win the war and might well lose it. Lloyd George agreed with Maurice Hankey, secretary of the Imperial War Cabinet, that he should talk to Andrew Bonar Law, the leader of the Conservative Party, about the situation. Bonar Law remained loyal to Asquith and so Lloyd George contacted Max Aitken instead and told him about his suggested reforms.

Lord Northcliffe joined with Lloyd George in attempting to persuade Asquith and several of his cabinet, including Sir Edward Grey, Arthur Balfour, Robert Crewe-Milnes, 1st Marquess of Crewe and Henry Petty-Fitzmaurice, 5th Marquess of Lansdowne, to resign. It was reported that Lloyd George was trying to encourage Asquith to establish a small War Council to run the war and if he did not agree he would resign.

Tom Clarke, the news editor of The Daily Mail, claims that Lord Northcliffe told him to take a message to the editor, Thomas Marlowe, that he was to run an article on the political crisis with the headline, "Asquith a National Danger". According to Clarke, Marlowe "put the brake on the Chief's impetuosity" and instead used the headline "The Limpets: A National Danger". He also told Clarke to print pictures of Lloyd George and Asquith side by side: "Get a smiling picture of Lloyd George and get the worst possible picture of Asquith." Clarke told Northcliffe that this was "rather unkind, to say the least". Northcliffe replied: "Rough methods are needed if we are not to lose the war... it's the only way."

Those newspapers that supported the Liberal Party, became concerned that a leading supporter of the Conservative Party should be urging Asquith to resign. Alfred George Gardiner, the editor of The Daily News, objected to Lord Northcliffe's campaign against Asquith: "If the present Government falls, it will fall because Lord Northcliffe decreed that it should fall, and the Government that takes its place, no matter who compose it, will enter on its task as the tributary of Lord Northcliffe."

Asquith was in great difficulty but he did have Cabinet ministers who did not want Lloyd George as prime minister. Roy Jenkins has argued that he should have had a meeting with "Cecil, Chamberlain, Curzon and Long might have had considerable effect. To begin with, he would no doubt have found them wavering. But he was not without influence over them. In the course of the discussion their doubts about Lloyd George would have come to the surface, and the conclusion might have been that they would have stiffened Asquith, and he would have stiffened them." Lloyd George's biographer, John Grigg, disagrees with Jenkins. His research suggests that Asquith had very little support from Conservative Party members of the coalition government and if he had tried to use them against Lloyd George it would end in failure.

On 4th December, 1916, The Times praised David Lloyd George in his stand against the present "cumbrous methods of directing the war" and urged H. H. Asquith to accept the "alternative scheme" of the small War Council, that he had proposed. The newspaper went on to argue that Asquith should not be a member of the council and instead his qualities were "fitted better... to preserve the unity of the Nation". The Liberal Party supporting Manchester Guardian, referred to the humiliation of Asquith, whose "natural course would be either to resist the demand for a War Council, which would partly supersede him as Premier, or alternatively himself to resign."

H. H. Asquith came to the conclusion that Lloyd George had leaked embarrassing details of the conversation he had with Lloyd George, including the threat of resignation if he did not get what he wanted. That night he sent a note to Lloyd George: "Such productions as the leading article in today's Times, showing the infinite possibilities for misunderstanding and misrepresentation of such an arrangement as we discussed yesterday, make me at least doubtful of its feasibility. Unless the impression is at once corrected that I am being relegated to the position of an irresponsible spectator of the War, I cannot go on."

Lloyd George denied the charge of leaking information but admitted that Lord Northcliffe wanted to "smash" his government. However, he went on to argue that Northcliffe also wanted to hurt him and had to put up with his newspaper's "misrepresentations... for months". He added "Northcliffe would like to make this (the formation of a small War Committee) and any other arrangement under your Premiership impossible... I cannot restrain nor I fear influence Northcliffe."

At a Cabinet meeting the following day, Asquith refused to form a new War Council that did not include him. Lloyd George immediately resigned: "It is with great personal regret that I have come to this conclusion.... Nothing would have induced me to part now except an overwhelming sense that the course of action which has been pursued has put the country - and not merely the country, but throughout the world the principles for which you and I have always stood throughout our political lives - is the greatest peril that has ever overtaken them. As I am fully conscious of the importance of preserving national unity, I propose to give your Government complete support in the vigorous prosecution of the war; but unity without action is nothing but futile carnage, and I cannot be responsible for that."

Conservative members of the coalition made it clear that they would no longer be willing to serve under Asquith. At 7 p.m. he drove to Buckingham Palace and tendered his resignation to King George V. Apparently, he told J. H. Thomas, that on "the advice of close friends that it was impossible for Lloyd George to form a Cabinet" and believed that "the King would send for him before the day was out." Thomas replied "I, wanting him to continue, pointed out that this advice was sheer madness."

Asquith, who had been prime minister for over eight years, was replaced by Lloyd George. He brought in a War Cabinet that included only four other members: George Curzon, Alfred Milner, Andrew Bonar Law and Arthur Henderson. There was also the understanding that Arthur Balfour attended when foreign affairs were on the agenda. Lloyd George was therefore the only Liberal Party member in the War Cabinet. Lloyd George wanted Northcliffe to become a member of the War Cabinet, however, Henderson told him that if this happened he would resign and take away the support of the Labour Party from the government.

The Daily Chronicle attacked the role that Lord Northcliffe and the other Conservative Party supporting newspaper barons had removed a democratically elected government. It argued that the new government "will have to deal with the Press menace as well as the submarine menace; otherwise Ministries will be subject to tyranny and torture by daily attacks impugning their patriotism and earnestness to win the war."

On 9th December, 1916, The Daily Mail front page, under the headline, "THE PASSING OF THE FAILURES" had a series of photographs showing the outgoing ministers, H. H. Asquith, Edward Grey, Reginald McKenna, Richard Haldane, John Simon and Winston Churchill, with accompanying captions across their chests attacking their records in government. Northcliffe had ordered this feature, and congratulated the newspaper's picture department.

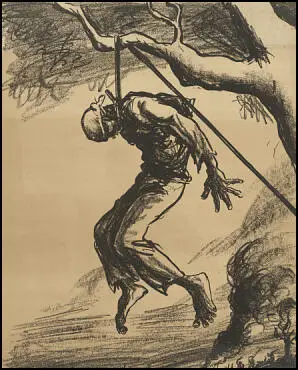

On this day in 1931 Edmund Duffy publishes a cartoon in the Baltimore Sun on the lynching of 23-year-old Mattthew Williams by a white mob in Salisbury, Maryland, two days previously. Duffy was one of the few white cartoonists willing to speak out against racial injustice. This included attacks on lynching and the Ku Klux Klan. Duffy supported the campaign led by Mary McLeod Bethune and Walter Francis White to persuade Congress to past an anti-lynching bill that had been proposed by Robert F. Wagner and Edward Costigan.

During Edmund Duffy's career, he won three Pulitzer Prizes. The cartoons were An Old Struggle Still Going On (27th February, 1930) that dealt with the struggle between communism and capitalism; California Points with Pride! (28th November, 1933) about California Governor James Rolph's reaction to the lynching of the killers of Brooke Hart and The Outstretched Hand (7th October, 1939) about Adolf Hitler and the invasion of Poland. Duffy died on 12th September 1962.

On this day in 1941 the Manhattan Project begins in Los Angeles, Calfornia. It was set-up under the command of Brigadier General Leslie Groves. Scientists recruited to produce an atom bomb included Robert Oppenheimer (USA), David Bohm (USA), Leo Szilard (Hungary), Eugene Wigner (Hungary), Rudolf Peierls (Germany), Otto Frisch (Germany), Niels Bohr (Denmark), Felix Bloch (Switzerland), James Franck (Germany), James Chadwick (Britain), Emilio Segre (Italy), Enrico Fermi (Italy), Klaus Fuchs (Germany) and Edward Teller (Hungary).

Winston Churchill and Franklin D. Roosevelt were deeply concerned about the possibility that Germany would produce the atom bomb before the allies. At a conference held in Quebec in August, 1943, it was decided to try and disrupt the German nuclear programme. In February 1943, SOE saboteurs successfully planted a bomb in the Rjukan nitrates factory in Norway. As soon as it was rebuilt it was destroyed by 150 US bombers in November, 1943. Two months later the Norwegian resistance managed to sink a German boat carrying vital supplies for its nuclear programme.

Meanwhile the scientists working on the Manhattan Project were developing atom bombs using uranium and plutonium. The first three completed bombs were successfully tested at Alamogordo, New Mexico on 16th July, 1945. James Chadwick later described what he saw during the test: "An intense pinpoint of light which grew rapidly to a great ball. Looking sideways, I could see that the hills and desert around us were bathed in radiance, as if the sun had been turned on by a switch. The light began to diminish but, peeping round my dark glass, the ball of fire was still blindingly bright ... The ball had then turned through orange to red and was surrounded by a purple luminosity. It was connected to the ground by a short grey stem, resembling a mushroom."

By the time the atom bomb was ready to be used Germany had surrendered. James Franck and Leo Szilard drafted a petition signed by just under 70 scientists opposed to the use of the bomb on moral grounds. Franck pointed out in his letter to Truman: "The military advantages and the saving of American lives achieved by the sudden use of atomic bombs against Japan may be outweighed by the ensuing loss of confidence and by a wave of horror and repulsion sweeping over the rest of the world and perhaps even dividing public opinion at home. From this point of view, a demonstration of the new weapon might best be made, before the yes of representatives of all the United Nations, on the desert or a barren island. The best possible atmosphere for the achievement of an international agreement could be achieved if America could say to the world, "You see what sort of a weapon we had but did not use. We are ready to renounce its use in the future if other nations join us-in this renunciation and agree to the establishment of an efficient international control."

However, the advice of the scientists was ignored by Harry S. Truman, the USA's new president, and he decided to use the bomb on Japan. General Dwight Eisenhower agreed with the scientists: "I voiced to him my grave misgivings, first on the basis of my belief that Japan was already defeated and that dropping the bomb was completely unnecessary, and secondly because I thought that our country should avoid shocking world opinion by the use of a weapon whose employment was, I thought, no longer mandatory as a measure to save American lives. It was my belief that Japan was, at that very moment, seeking some way to surrender with a minimum loss of face."

At Yalta, the Allies had attempted to persuade Joseph Stalin to join in the war with Japan. By the time the Potsdam meeting took place, they were having doubts about this strategy. Winston Churchill in particular, were afraid that Soviet involvement would lead to an increase in their influence over countries in the Far East. On 17th July 1945 Stalin announced that he intended to enter the war against Japan.

President Truman now insisted that the bomb should be used before the Red Army joined the war against Japan. Leslie Groves, the head of the Manhattan Project, wanted the target to be Kyoto because as it had been untouched during previous attacks, the dropping of the atom bomb on it would show the destructive power of the new weapon. However, the Secretary of War, Henry Stimson, argued strongly against this as Kyoto was Japan's ancient capital, a city of immense religious, historical and cultural significance. General Henry Arnold supported Stimson and Truman eventually backed down on this issue.

President Truman wrote in his journal on 25th July, 1945: "This weapon is to be used against Japan between now and August 10th. I have told the Secretary of War, Mr Stimson, to use it so that military objectives and soldiers and sailors are the target and not women and children. Even if the Japs are savages, ruthless, merciless and fanatic, we, as leader of the world for the common welfare cannot drop this terrible bomb on the old capital or the new. He & I are in accord. The target will be a purely military."

Truman's military advisers accepted that Kyoto would not be targeted but insisted that another built-up area should be chosen instead: "While the bombs should not concentrate on civilian areas, they should seek to make a profound a psychological impression as possible. The most desirable target would be a vital war plant employing a large number of workers and closely surrounded by workers' houses."

Winston Churchill insisted that two British representives should witness the dropping of the atom bomb. Squadron Leader Leonard Cheshire and William Penny, a scientist working on the Manhattan Project, were chosen for this task. Churchill ordered them to learn "about the taqctical aspects of using such a weapon, reach a conclusion about its future implications for air warfare and report back to the Prime Minister."

General Thomas Farrell, Commander of the Manhattan Project, explained to Cheshire and Penny that they had produced two types of bomb. Fat Man relied upon implosion: a 12 lb sphere of plutonium would be abruptly squeezed to super-critically by the detonation of an envelope of explosive. Little Boy functioned by a gun mechanism which fired two subcritical masses of uranium 235 together.

President Harry S. Truman eventually decided that the bomb should be dropped on Hiroshima. It was the largest city in the Japanese homeland (except Kyoto) which remained undamaged, and a place of military industry. However, Truman, after listening from advice of General Curtis LeMay, refused permission for Leonard Cheshire and William Penny to witness the event. Leslie Groves, according to Cheshire, "said firmly that there was no room for either of us; in any case he couldn't see why we needed to be there, for we would receive a full written report and could ask to see any documentation we wanted."

On 6th August 1945, a B29 bomber piloted by Paul Tibbets, dropped an atom bomb on Hiroshima. Michihiko Hachiya was living in the city at the time: "Hundreds of people who were trying to escape to the hills passed our house. The sight of them was almost unbearable. Their faces and hands were burnt and swollen; and great sheets of skin had peeled away from their tissues to hang down like rags or a scarecrow. They moved like a line of ants. All through the night, they went past our house, but this morning they stopped. I found them lying so thick on both sides of the road that it was impossible to pass without stepping on them."

Later that day President Harry S. Truman made a speech where he argued: "The harnessing of the basic power of the universe. The force from which the sun draws its power has been used against those who brought war to the Far East. We have spent $2,000,000,000 (about $500,000,000) on the greatest gamble in history, and we have won. With this bomb we have now added a new and revolutionary increase in destruction to supplement the growing power of our armed forces. In their present form these bombs are now in production and even more powerful forms are in development."

Truman then issued a warning to the Japanese government: "We are now prepared to obliterate more rapidly and completely every productive enterprise the Japanese have above ground in any city. We shall destroy their docks, their factories and their communications. Let there be no mistake, we shall completely destroy Japan's power to make war. It was to spare the Japanese people from utter destruction that the ultimatum of July 26 was issued from Potsdam. Their leaders promptly rejected that ultimatum. If they do not now accept our terms they may expect a rain of run from the air the like of which has never been seen on this earth. Behind this air attack will follow sea and land forces in such numbers and power as they have not yet seen and with a fighting skill of which they have already become well aware."

Hideki Tojo, Japan's Foreign Minister, told Emperor Hirohito on 8th August, 1945, that Hiroshima had been obliterated by an atom bomb and advised surrender. Others raised doubts about whether the United States had more than one of these bombs. The Supreme Council decided to convene a meeting on the morning of 9th August. As they had not immediately surrendered President Truman ordered that a second atom bomb should be dropped on Japan.

Major Charles Sweeney was selected to lead the mission and Nagasaki was chosen as the target. This time it was agreed that Leonard Cheshire and William Penny, could travel on the aircraft that was to take photographs of the attack on 9th August. When they reached Nagasaki they found the city covered in cloud and Kermit Beahan, the bombardier, was at first unable to find the target. Eventually, the cloud parted and Beahan dropped the bomb a mile and a half from the intended aiming point.

William Laurence was a journalist who was invited by Leslie Groves to be on Sweeney's aircraft: "We watched a giant pillar of purple fire, 10,000 feet high, shoot up like a meteor coming from the earth instead of outer space. It was no longer smoke, or dust, or even a cloud of fire. It was a living thing, a new species of being, born before our incredulous eyes. Even as we watched, a ground mushroom came shooting out of the top to 45,000 feet, a mushroom top that was even more alive than the pillar, seething and boiling in a white fury of creamy foam, a thousand geysers rolled into one. It kept struggling in elemental fury, like a creature in the act of breaking the bonds that held it down. When we last saw it, it had changed into a flower-like form, its giant petals curving downwards, creamy-white outside, rose-coloured inside. The boiling pillar had become a giant mountain of jumbled rainbows. Much living substance had gone into those rainbows."

Cheshire later recalled in his book, The Light of Many Suns (1985): "The ultra-dark glasses we each had round our foreheads to protect our eyes from the blinding light of the bomb were not needed because we were about fifty miles away. By the time I saw it, the flash had turned into a vast fire-ball which slowly became dense smoke, 2,000 feet above the ground, half a mile in diameter and rocketing upwards at the rate of something like 20,000 feet a minute. I was overcome, not by its size, nor by its speed of ascent but by what appeared to me its perfect and faultless symmetry. In this it was unique, above every explosion that I had ever heard of or seen, the more frightening because it gave the impression of having its immense power under full and deadly control.... The cloud lifted itself to 60,000 feet where it remained stationary, a good two miles in diameter, sulphurous and boiling. Beneath it, stretching right down to the ground was a revolving column of yellow smoke, fanning out at the bottom to a dark pyramid, wider at its base than was the cloud at its climax. The darkness of the pyramid was due to dirt and dust which one could see being sucked up by the heat. All around it, extending perhaps another mile, were springing up a mass of separate fires. I wondered what could have caused them all."

Fumiko Miura was a 16 year-old girl working in Nagasaki at the time: "I was doing some clerical work for the Japanese imperial army. At about 11 o'clock, I thought I heard the throbs of a B-29 circling over the two-storey army headquarters building. I wondered why an American bomber was flying around above us when we had been given the all-clear.... At that moment, a horrible flash, thousands of times as powerful as lightning, hit me. I felt that it almost rooted out my eyes. Thinking that a huge bomb had exploded above our building, I jumped up from my seat and was hit by a tremendous wind, which smashed down windows, doors, ceilings and walls, and shook the whole building. I remember trying to run for the stairs before being knocked to the floor and losing consciousness. It was a hot blast, carrying splinters of glass and concrete debris. But it did not have that burning heat of the hypocentre, where everyone and everything was melted in an instant by the heat flash. I learned later that the heat decreased with distance. I was 2,800m away from the hypocentre."

After a long debate Emperor Hirohito intervened and said he could no longer bear to see his people suffer in this way. On 15th August the people of Japan heard the Emperor's voice for the first time when he announced the unconditional surrender and the end of the war. Naruhiko Higashikuni was appointed as head of the surrender government.

On this day in 1944 the Heinkel He 162A makes its first flight. Throughout the Second World War both the Royal Air Force and the Luftwaffe attempted to produce an effective jet aeroplane. Hans Ohain, who was employed by the Ernst Heinkel company, developed the HE 178, but it was not a successful aircraft. The Heinkel He 162A did not make its first flight until 6th December, 1944. It was not a success as an under-carriage door came off. Four days later on another test flight it crashed when one of its wings disintegrated. Changes were made and 300 were built but very few saw action before the end of the Second World War.

On this day in 1952 Cicely Mary Hamilton died. Hamilton, the daughter of Danzil Hammill and Maude Piers, was born in Paddington on 15th June 1872. At the time of the birth, Hammill was a captain in the Gordon Highlanders. When Cicely was ten years old, her mother disappeared from her life. Although Cicely always refused to talk about the matter, it is believed her mother was committed to an asylum. With Hammill serving in Egypt, Cicely was brought up by foster parents.

After an education at a boarding school in Malvern, Cicely became a pupil-teacher. She disliked the work and soon found employment as an actress with a touring company. It was during this time she changed her name from Hammill to Hamilton. In 1897 Hamilton joined a Shakespearian company led by the American actor, Edmund Tearle. Over the next few years she appeared as Gertrude in Hamlet, Emilia in Othello and one of the witches in Macbeth.

Unable to obtain leading roles on the London stage, Hamilton decided to turn to writing. Her first play, The Traveller Returns, was performed at the Pier Theatre, Brighton, in May 1906. This was followed by Diana of Dobsons. The play was an immediate success and ran at the Kingsway, London, for 143 performances.

In 1908 Hamilton joined the Women's Social and Political Union. However, Hamilton disliked the autocratic way that Emmeline Pankhurst ran the organisation and after a few months left to join the Women's Freedom League. She was also a founder member of the Actresses' Franchise League and the Women Writers Suffrage League. Hamilton wrote two propaganda plays, How the Vote was Won (1909) and A Pageant of Great Women. She also joined with the composer, Ethel Smythe, to write March of the Women.

Hamilton's most important contribution to the feminist movement was the influential, Marriage as a Trade (1909). In the book Hamilton argued that woman were brought up to look for success only in the marriage market and this severely damaged their intellectual development. She followed this with the novel, Just to Get Married (1911) that explores the degrading scheming of the heroine to ensnare a husband.

On the outbreak of the First World War, Elsie Inglis, one of the founders of the Scottish Women's Suffrage Federation, suggested that women's medical units should be allowed to serve on the Western Front. With the financial support of the National Union of Women's Suffrage Societies (NUWSS), Inglis formed the Scottish Women's HospitalsCommittee. Hamilton was one of the first women to join the organisation and in November 1914 helped to establish the 200 bed Auxiliary Hospital at Royaumont Abbey in France.

In the summer of 1916 Hamilton helped nurse soldiers wounded at the Battle of the Somme. This included treating 300 new patients in three days. Others who worked with her at Royaumont Abbey included Elsie Inglis, Louisa Martindale, Evelina Haverfield and Ishobel Ross.

In May 1917 Hamilton left the Scottish Women's Hospital Unit and joined the Women's Auxiliary Army Corps. After training in England, Hamilton returned to France where she took control of a postal unit. However, soon afterwards, she was asked to form a repertory company at the Somme. For the rest of the war Hamilton's company performed a series of plays for Allied soldiers fighting on the Western Front.

After the war Hamilton became a freelance journalist working for newspapers such as the Daily Mail, the Daily Mirror and the Daily Express. She was also a regular contributor to the feminist journal, Time and Tide where she campaigned for free birth control advice for women and the legalization of abortion.

Hamilton's autobiography Life Errant, was published in 1935. Other books written by Hamilton include Modern Italy (1932), Modern France (1933), Modern Russia (1934), Modern England (1938), Lament for Democracy (1940) and The Englishwoman (1940). Cicely Mary Hamilton died on 6th December, 1952.