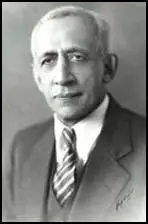

Edward Costigan

Edward Costigan was born Beaulahville on 1st July, 1874. A few years later the family moved to Colorado. He graduated from Harvard University in 1899 and began work as a lawyer in Denver in 1900.

Costigan had been a member of the Republican Party but in 1912 helped to form the Progressive Party in Colorado. Later that year he failed in his attempt to become Governor of Colorado.

In 1917 President Woodrow Wilson appointed Costigan as a member of the United States Tariff Commission. He served on the commission until resigning in March 1928. Costigan, now a member of the Democratic Party, was elected to the Senate in 1930.

After he was elected President Franklin D. Roosevelt initially opposed massive public works spending. However, by the spring of 1933, the needs of more than fifteen million unemployed had overwhelmed the resources of local governments. In some areas, as many as 90 per cent of the people were on relief and it was clear something needed to be done. Costigan, Frances Perkins, Harry Hopkins, Rexford Tugwell, Robert LaFollette Jr. Robert Wagner, Fiorello LaGuardia and George Norris eventually won him over.

On 9th March 1933, Roosevelt called a special session of Congress. He told the members that unemployment could only be solved "by direct recruiting by the Government itself." For the next three months, Roosevelt proposed, and Congress passed, a series of important bills that attempted to deal with the problem of unemployment. The special session of Congress became known as the Hundred Days and provided the basis for Roosevelt's New Deal.

The NAACP hoped that the election of Franklin D. Roosevelt would bring an end to lynching. Two African American campaigners against lynching, Mary McLeod Bethune and Walter Francis White, had been actively involved in helping Roosevelt to obtain victory. The president's wife, Eleanor Roosevelt, had also been a long-time opponent of lynching.

Costigan and Robert F. Wagner agreed to draft a bill that would punish the crime of lynching. In 1935 attempts were made to persuade Roosevelt to support the Costigan-Wagner Bill. However, Roosevelt refused to speak out in favour of the bill that would punish sheriffs who failed to protect their prisoners from lynch mobs. He argued that the white voters in the South would never forgive him if he supported the bill and he would therefore lose the next election.

Even the appearance in the newspapers of the lynching of Rubin Stacy failed to change Roosevelt's mind on the subject. Six deputies were escorting Stacy to Dade County jail in Miami on 19th July, 1935, when he was taken by a white mob and hanged by the side of the home of Marion Jones, the woman who had made the original complaint against him. The New York Times later revealed that "subsequent investigation revealed that Stacy, a homeless tenant farmer, had gone to the house to ask for food; the woman became frightened and screamed when she saw Stacy's face."

The Costigan-Wagner received support from many members of Congress but the Southern opposition managed to defeat it. However, the national debate that took place over the issue helped to bring attention to the crime of lynching.

Edward Costigan retired from Congress on 3rd January, 1937. He returned to work as a lawyer in Denver and remained there until his death on 17th January, 1939.

Primary Sources

(1) Costigan-Wagner Bill, 73rd Congress, 2nd Session (3rd January, 1935)

A bill to assure to persons within the jurisdiction of every State the equal protection of the laws, and punish the crime of lynching

Be it enacted by the Senate and House of Representatives of the United States of America in Congress assembled, That, for the purposes of this Act, the phrase “mob or riotous assemblage”, when used in this Act, shall mean an assemblage composed of three or more persons acting in concert, without authority of law, [for the purpose of depriving any person of his life, or doing him physical injury] to kill or injure any person in the custody of any peace officer, with the purpose or consequence of depriving such person of due process of law or the equal protection of the laws.

Sec. 2. If any state or governmental, subdivision thereof fails, neglects, or refuses to provide and maintain protection to the life or person of any individual within its jurisdiction against a mob or riotous assemblage, whether by way of preventing or punishing the acts thereof, such State shall by reason of such failure, neglect, or refusal be deemed to have denied to such person due process of law and the equal protection of the laws of the State, and to the end that the protection guaranteed to persons within the jurisdiction of the United States, may be secured, the provisions of this Act are enacted.

Sec. 3. (a) Any officer or employee of any State or governmental subdivision thereof who is charged with the duty or who possesses the power or authority as such officer or employee to protect the life or person of any individual injured or put to death by any mob or riotous assemblage or any officer or employee of any State or governmental subdivision thereof having any such individual in his [change as a prisoner] custody, who fails, neglects, or refuses to make all diligent efforts to protect such individual from being so injured or being put to death, or any officer or employee of any State or governmental subdivision thereof charged with the duty of apprehending, keeping in custody, or prosecuting any person participating in such mob or riotous assemblage who fails, neglects, or refuses to make all diligent efforts to perform his duty in apprehending, keeping in custody, or prosecuting to final judgment under the laws of such State all persons so participating, shall be guilty of a felony, and upon conviction thereof shall be punished by a fine not exceeding $5,000 or by imprisonment not exceeding five years, or by both such fine and imprisonment.

(b) Any officer or employee of any state or governmental subdivision thereof, acting as such officer or employee under authority of State law, having in his custody or control a prisoner, who shall conspire, combine, or confederate with any person who is a member of a mob or riotous assemblage to injure or put such prisoner to death without authority of law, or who shall conspire, combine, or confederate with any person to suffer such prisoner to be taken or obtained from his custody or control [for the purpose of being] to be injured or put to death [without authority of law] by a mob or riotous assemblage shall be guilty of a felony, and those who so conspire, combine, or confederate with such officer or employee shall likewise be guilty of a felony. On conviction the parties participating therein shall be punished by imprisonment of not less than five years or [for life] not more than twenty-five years.

Sec. 4. The District Court of the United States judicial district wherein the person is injured or put to death by a mob or riotous assemblage shall have jurisdiction to try and to punish, in accordance with the laws of the State where the injury is inflicted or the homicide is committed, any and all persons who participate therein: Provided, That it is first made to appear to such court (1) that the officers of the State charged with the duty of apprehending, prosecuting, and punishing such offenders under the laws of the State shall have failed, neglected, or refused to apprehend, prosecute, or punish such offenders; or (2) that the jurors obtainable for service in the State court having jurisdiction of the offense are so strongly opposed to such punishment that there is [no] probability that those guilty of the offense [can be] will not be punished in such State court. A failure for more than thirty days after the commission of such an offense to apprehend or to indict the persons guilty thereof, or a failure diligently to prosecute such persons, shall be sufficient to constitute prima facie evidence of the failure, neglect, or refusal described in the above proviso.

Sec. 5. Any county in which a person is seriously injured or put to death by a mob or riotous assemblage shall [forfeit $10,000, which sum may be recovered by suit therefor in the name of the United States against such county for the use of the family, if any, of the person so put to death; if he had no family then of his dependent parents, if any; otherwise for the use of the United States] be liable to the injured person or the legal representatives of such person for a sum of not less than $2,000 nor more than $10,000 as liquidated damages, which sum may be recovered in a civil action against such county in the United States District Court of the judicial district wherein such person is put to the injury or death. Such action shall be brought and prosecuted by the United States district attorney [of the United States] of the district in the United States District Court for such district. If such [forfeiture] amount awarded be not paid upon recovery of a judgment thereof, such court shall have jurisdiction to enforce payment thereof by levy of execution upon any property of the county, or may otherwise compel payment thereof by mandamus or other appropriate process; and any officer of such county or other person who disobeys or fails to comply with any lawful order of the court in the premises shall be liable to punishment as for contempt and to any other penalty provided by law therefor. The amount recovered shall be exempt from all claims by creditors of the deceased. The amount recovered upon such judgment shall be paid to the injured person, or where death resulted, distributed in accordance with the laws governing the distribution of an intestate decendent’s assets then in effect in the State wherein such death occurred.

Sec. 6. In the event that any person so put to death shall have been transported by such mob or riotous assemblage from one county to another county during the time intervening between his seizure and putting to death, the county in which he is seized and the county I which he is put to death shall be jointly and severally liable to pay the forfeiture herein provided. Any district judge of the United States District Court of the judicial district wherein any suit or prosecution is instituted under the provisions of this Act, may by order district that such suit or prosecution be tried in any place in such district as he may designate in such order.

Sec. 7. Any act committed in any State or Territory of the United States in violation of the rights of a citizen or subject of a foreign country secured to such citizen or subject by treaty between the United States and such foreign country, which act constitute a like crime against the peace and dignity of the United States, punishable in a like manner in its courts as in the courts of said State or Territory, and able in a like manner in its courts as in the courts of said State or Territory, and may be prosecuted in the courts of the United States, and upon conviction the sentence executed in like manner as sentences upon convictions for crimes under the laws of the United States.]

Sec. 8. If any provision of this Act or the application thereof to any person or circumstances is held invalid, the remainder of the Act, and the application of such provision to other persons or circumstances, shall not be affected thereby.]

(2) Handbill, What You Can Do To Stop Lynching, published in January 1935.

The Costigan Wagner anti-lynching bill will be introduced into Congress on January 3, 1935. A group of national organizations, all vitally interested in the eradication of lynching, have chosen the week of January 6 as the time when citizens of the United States should voice their feeling on this bill in the following ways:

1. Write or telegraph President Franklin D. Roosevelt, The White House, Washington, D.C., asking him to insist that the Costigan-Wagner anti-lynching bill be brought to a vote at this session of Congress and to use his influence to secure its passage.

2. Write or telegraph Joseph T. Robinson, Majority Leader of the Senate, Senate Office Building, Washington, DC, asking him to put the Costigan-Wagner anti-lynching bill on the calendar for debate and vote at the earliest possible time.

3. Write or telegraph the two United States senators from your state, addressing them at the Senate Office Building, Washington, DC, asking them to help bring the Costigan-Wagner anti-lynching bill to a vote and to vote for its passage.

4. Write or telegraph the Congressman from your district, addressing him at the House Office Building, Washington, DC, asking him to work for the passage of the Costigan-Wagner anti-lynching bill and to use his influence with other Congressmen.

The Costigan-Wagner anti-lynching bill, but putting the prosecution of lynchers into the Federal court, will provide the same kind of effective action as is now being taken in kidnapping cases.

(3) Roy Wilkins interviewed Huey P. Long for The Crisis in February, 1935.

"How about lynching, Senator? About the Costigan-Wagner bill in congress and that lynching down there yesterday in Franklinton..."

He ducked the Costigan-Wagner bill, but of course, everyone knows he is against it. He cut me off on the Franklinton lynching and hastened in with his "pat" explanation:

"You mean down in Washington parish (county)? Oh, that? That one slipped up on us. Too bad, but those slips will happen. You know while I was governor there were no lynchings and since this man (Governor Allen) has been in he hasn't had any. (There have been 7 lynchings in Louisiana in the last two years.) This one slipped up. I can't do nothing about it. No sir. Can't do the dead nigra no good. Why, if I tried to go after those lynchers it might cause a hundred more ******s to be killed. You wouldn't want that, would you?"

"But you control Louisiana," I persisted, "you could..."

"Yeah, but it's not that simple. I told you there are some things even Huey Long can't get away with. We'll just have to watch out for the next one. Anyway that ****** was guilty of coldblooded murder."

"But your own supreme court had just granted him a new trial."

"Sure we got a law which allows a reversal on technical points. This ****** got hold of a smart lawyer somewhere and proved a technicality. He was guilty as hell. But we'll catch the next lynching."