On this day on 21st November

On this day in 1865 the Kensington Society discussed the topic of parliamentary reform. Earlier that year a group of women in London formed a discussion group called the Kensington Society. It was given this name because they held their meetings at 44 Phillimore Gardens in Kensington. One of the founders of the group was Alice Westlake. On 18th March, Westlake wrote to Helen Taylor inviting her to join the group. She claimed that "none but intellectual women are admitted and therefore it is not likely to become a merely puerile and gossiping Society." Westlake followed this with another letter on the 28th March: "There are very few few of the members whom you will know by name... the object of the Society is chiefly to serve as a sort of link, though a slight one, between persons, above the average of thoughtfulness and intelligence who are interested in common subjects, but who had not many opportunities of mutual intercourse."

Nine of the eleven women who attended the early meetings were unmarried and were attempting to pursue a career in education or medicine. The group eventually included Barbara Bodichon, Jessie Boucherett, Emily Davies, Francis Mary Buss, Dorothea Beale, Anne Clough, Louisa Smith, Alice Westlake, Katherine Hare, Harriet Cook, Helen Taylor, Elizabeth Wolstenholme-Elmy and Elizabeth Garrett.

On 21st November 1865, the women discussed the topic of parliamentary reform. The question was: "Is the extension of the Parliamentary suffrage to women desirable, and if so, under what conditions?. Both Barbara Bodichon and Helen Taylor submitted a paper on the topic. The women thought it was unfair that women were not allowed to vote in parliamentary elections. They therefore decided to draft a petition asking Parliament to grant women the vote.

The women took their petition to Henry Fawcett and John Stuart Mill, two MPs who supported universal suffrage. Louisa Garrett Anderson later recalled: "John Stuart Mill agreed to present a petition from women householders… On 7th June 1866 the petition with 1,500 signatures was taken to the House of Commons. It was in the name of Barbara Bodichon and others, but some of the active promoters could not come and the honour of presenting it fell to Emily Davies and Elizabeth Garrett…. Elizabeth Garrett liked to be ahead of time, so the delegation arrived early in the Great Hall, Westminster, she with the roll of parchment in her arms. It made a large parcel and she felt conspicuous. To avoid attracting attention she turned to the only woman who seemed, among the hurrying men, to be a permanent resident in that great shrine of memories, the apple-woman, who agreed to hide the precious scroll under her stand; but, learning what it was, insisted first on adding her signature, so the parcel had to be unrolled again." Mill added an amendment to the 1867 Reform Act that would give women the same political rights as men but it was defeated by 196 votes to 73.

Members of the Kensington Society were very disappointed when they heard the news and they decided to form the London Society for Women's Suffrage. Soon afterwards similar societies were formed in other large towns in Britain. Eventually seventeen of these groups joined together to form the National Union of Women's Suffrage Societies.

On this day in 1870, Alexander Berkman, the son of a Jewish businessman was born in Vilnius, the capital of Lithuania. Berkman grew up in comfortable surroundings, that including servants and a summer house. He attended a gymnasium reserved for the privileged elements of society.

On 1st March, 1881, Tsar Alexander II was assassinated. The bomb blast shattered the windows of his classroom. That evening, his older brother, who sympathized with the revolutionists, told him that he had been killed by the People's Will. As the author of Anarchist Portraits (1995), has pointed out, Berkman "was deeply moved by the martyrdom of the populists, five of whom were hanged for their part in the assassination. He was inspired by their idealism and courage, and from that time forward their example lingered in his thoughts."

His mother's brother, Mark Natanson, was a close friend of Peter Kropotkin, and was also involved in revolutionary activity. Berkman was later to write that Natanson was "my ideal of a noble and great man". At the age of fifteen he was already reading revolutionary literature and was expelled from school for "precocious godlessness, dangerous tendencies, and insubordination."

Berkman also became aware of the racism in Russia for when his father died, the family was deprived of the right to live in the capital and were forced to live in Kovno, a town in the Jewish Pale of Settlement. In 1887 his mother died and the following year he decided to move to the United States.

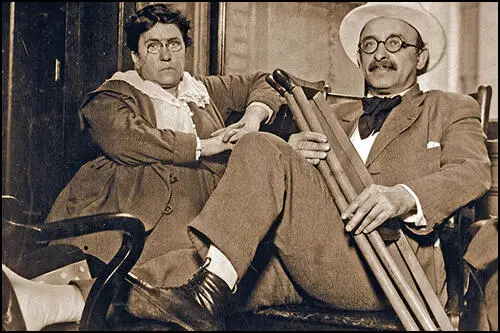

On his arrival in New York City Berkman joined the principal Jewish anarchist group, Pioneers of Liberty. Soon afterwards he began living with Emma Goldman, a Russian immigrant who was working in a clothing factory in Rochester. Berkman and Goldman both became involved in the campaign to free the men convicted of the Haymarket Bombing. They were also influenced by the anarchist writings of Johann Most.

In 1892 Berkman and Goldman started a small business in Worcester, Massachusetts, providing lunches for local workers. Later that year Amalgamated Iron and Steel Workers Union called out its members at the Steel Homestead plant owned by Henry Frick and Andrew Carnegie. Frick took the controversial decision to employ 300 strikebreakers from the Pinkerton Detective Agency. The men were brought in on armed barges down the Monongahela River. The strikers were waiting for them and a day long battle took place. Ten men were killed and 60 wounded before the governor obtained order by placing Homestead under martial law.

Berkman was appalled by Frick's behaviour and decided to make a dramatic gesture against capitalism. After gaining entry into his office, Berkman shot Henry Frick three times and stabbed him twice. However, Frick survived the attack and made a full-recovery. Found guilty of attempted murder, Berkman was sent to Western Penitentiary of Pennsylvania in Allegheny City.

After ten years in prison, Berkman wrote to Emma Goldman: "My youthful ideal of a free humanity in tile vague future, has become clarified and crystallized into the living truth of Anarchy, as the sustaining elemental force of my everyday existence." Berkman was released in 1906. He wrote that "I feel like one recovering from a long illness: very weak, but with a touch of joy in life."

After the death of Johann Most, Berkman and Emma Goldman became the leaders of the anarchist movement in the United States. They published the radical journal, Mother Earth and books such as Goldman's Anarchism and Other Essays (1910) and Berkman's Prison Memoirs of an Anarchist (1912). They also helped organize the Ferrer School in New York City and industrial disputes such as the Lawrence Textile Strike.

On the outbreak of the First World War both Berkman and Emma Goldman became involved in the campaign to keep the United States out of the conflict. They also organized anti-militarist rallies in New York City and went on several lecture tours in an attempt to "arouse public opinion against the growing war hysteria".

Berkman moved to San Francisco and in January, 1916, started a new anarchist journal, Blast. When five months later a bomb went off killing six people in the city. The authorities suspected that the bomb had been planted by anti-war campaigners and Berkman was arrested but later released. Thomas Mooney, a local trade union leader was falsely convicted of the offence but spent the next twenty-three years in prison before being released.

In 1919 Woodrow Wilson appointed A. Mitchell Palmer as his attorney general. Soon after taking office, a government list of 62 people believed to hold "dangerous, destructive and anarchistic sentiments" was leaked to the press. It was also revealed that these people had been under government surveillance for many years. Worried by the revolution that had taken place in Russia, Palmer became convinced that Communist agents were planning to overthrow the American government. Palmer recruited John Edgar Hoover as his special assistant and together they used the Espionage Act (1917) and the Sedition Act (1918) to launch a campaign against radicals and left-wing organizations.

A. Mitchell Palmer claimed that Communist agents from Russia were planning to overthrow the American government. On 7th November, 1919, the second anniversary of the Russian Revolution, over 10,000 suspected communists and anarchists were arrested. Palmer and Hoover found no evidence of a proposed revolution but large number of these suspects were held without trial for a long time. The vast majority were eventually released but Alexander Berkman, Emma Goldman, Mollie Steimer, and 245 other people, were deported to Russia.

Henry L. Mencken wrote that "Berkman was a transparently honest man yet we hunt him as if he were a mad dog - and finally kick him out of the country. And with him goes a shrewder head and a braver spirit than has been seen in public among us since the American Civil War."

In January 1920 Berkman and Goldman toured Russia collecting material for the Museum of the Revolution in Petrograd. However, Lenin was a strong opponent of anarchism. He told Nestor Makhno, the most important anarchist in Russia: "The majority of anarchists think and write about the future without understanding the present. That is what divides us Communists from them."

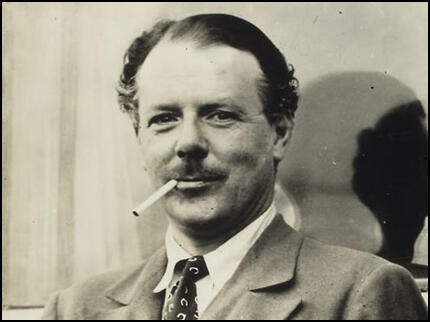

On this day in 1886 Harold Nicolson, the third son of Arthur Nicolson, first Baron Carnock, and his wife, Mary Katharine Rowan was born in Teheran. His father was a diplomat and his childhood was spent in Turkey, Spain, Morocco and Russia.

In October 1909, Nicolson passed second in the competitive entrance examination for the diplomatic service. He spent his early years in the service as an attaché at Madrid. In June 1910 Harold met Vita Sackville-West for the first time. Harold visited Vita in Monte Carlo in January 1911: Vita recorded: "He was as gay and clever as ever, and I loved his brain and his youth, and was flattered at his liking for me. He came to Knole a good deal that autumn and winter, and people began to tell me he was in love with me, which I didn't believe was true, but wished that I could believe it. I wasn't in love with him then - there was Rosamund - but I did like him better than anyone, as a companion and playfellow, and for his brain and his delicious disposition."

Vita Sackville-West was a lesbian and at this time was having affairs with Violet Keppel and Rosamund Grosvenor. In January 1912 Nicolson proposed to Vita. She refused him but under pressure from her mother, Victoria Sackville-West, Vita agreed to become engaged. As a result of the engagement, her mother gave her an allowance of £2,500 a year, of which the capital was to become hers on her mother's death. Later that month he was appointed as third secretary at Constantinople.

Harold Nicholson became concerned about Vita's relationship with Rosamund Grosvenor. He was puzzled by Rosamund's subservient attitude to Vita. He mentioned this in a letter to Vita, who replied: "It is a pity and rather tiresome. But doesn't everyone want one subservient person in your life? I've got mine in her. Who is yours? Certainly not me!" Vita later wrote in her autobiography: "It did not seem wrong to be... engaged to Harold, and at the same time so much in love with Rosamund... Our relationship (with Harold Nicholson) was so fresh, so intellectual, so unphysical, that I never thought of him in that aspect at all.... Some were born to be lovers, others to be husbands, he belongs to the latter category."

Rosamund Grosvenor became jealous of Vita's relationships with Harold Nicholson, Violet Keppel and Muriel Clark-Kerr, the sister of Archibald Clark-Kerr. Rosamund wrote to Vita: "Oh my sweet you do know don't you. Nothing can ever make me love you less whatever happens, and I really think you have taken all my love already as there seems very little left." After one love-making session she wrote: "My sweet darling... I do miss you darling one and I want to feel your soft cool face coming out of that mass of pussy fur like I did last night."

Despite having several affairs with women, Vita Sackville-West married Harold Nicholson on 1st October, 1913 at Knole House, the family home. They spent their honeymoon in Spain and Italy. Their first son, Lionel Benedict Nicolson, was born on 6th August 1914. They lived both in London and at Long Barn, a house near Sevenoaks. A second son was stillborn in 1915, and their last child, Nigel Nicolson, was born in London in 1917.

During the First World War Nicolson worked for the Foreign Office. Along with Mark Sykes and Leo Amery, he was one of the chief draftsmen of the Balfour Declaration, which committed Britain to supporting a Jewish homeland in Palestine. As a junior Foreign Office official Nicolson attended the Versailles Peace Conference after the Armistice. After the conference he was appointed private secretary to Eric Drummond, the first secretary-general of the infant League of Nations.

In April 1918 Vita Sackville-West resumed her affair with Violet Keppel. Vita later wrote: "She lay on the sofa, I sat plunged in the armchair; she took my hands, and parted my fingers to count the points as she told me why she loved me... She pulled me down until I kissed her - I had not done so for many years." The lovers travelled around Europe and collaborated on a novel, Challenge (1923), that was published in America but banned in Britain.

Violet Keppel came under pressure from her mother, Alice Keppel, to bring an end to her affair with Vita Sackville-West. Reluctantly she married Denys Robert Trefusis, an officer in the Royal Horse Guards, on 16th June 1919. She did so on the understanding that the marriage would remain unconsummated, and she was still resolved to live with Vita. They resumed their affair just a few days after the wedding. The women moved to France in February 1920. However, Harold Nicholson followed them and eventually persuaded Vita to return to the family home.

T. J. Hochstrasser points out: "However, this crisis in fact proved eventually to be the catalyst for Nicolson and Sackville-West to restructure their marriage satisfactorily so that they could both pursue a series of relationships through which they could fulfil their essentially homosexual identity while retaining a secure basis of companionship and affection."

Harold's son, Nigel Nicolson, later wrote in his book, Portrait of a Marriage (1973): "When she (Vita) married Harold, she assumed that marriage was love by other means, and for a time it worked. The very existence of myself and my brother is proof of it, and there is ample evidence in the letters and diaries that for the first few years of their marriage they were sexually compatible. After 1917 it gradually became clear that their mutual enjoyment was on the wane.... Harold had a series of relationships with men who were his intellectual equals, but the physical element in them was very secondary. He was never a passionate lover. To him sex was as incidental, and about as pleasurable, as a quick visit to a picture-gallery between trains. His a-sexual love for Vita in later life was balanced by affection for his men friends, by some of whom he was temporarily, but never helplessly, attracted. There was no moment in his life when love for a young man became such an obsession to him that it interfered with his work, and he had no affairs faintly comparable to Vita's. Their behaviour in this respect was a reflection of their very different personalities. His life was too well regulated to be affected by affairs of the heart, while she always allowed herself to be swept away."

Nicolson became the private secretary of Lord Curzon, the Foreign Secretary, at several important conferences and was Britain's representative on a number of subcommittees. In 1925 he was transferred to Teheran as counsellor of legation. Although busy with diplomatic work he still found time to write several literary biographies: Tennyson (1923), Byron: the Last Journey (1924), and Swinburne (1926). In September 1929 Nicolson resigned from the diplomatic service in order to concentrate on his writing career.

In 1930, Harold Nicolson and Vita Sackville-West left Long Barn and purchased Sissinghurst Castle, which they set about restoring and developing into the setting for a large-scale garden. As T. J. Hochstrasser has pointed out: "Sissinghurst... the sketchy remains of a Kentish Elizabethan mansion, which they set about restoring and developing into the setting for a large-scale garden: this was a joint project where the principles of design were contributed by Nicolson and the planting schemes and maintenance by Sackville-West."

In 1931 Nicolson joined Sir Oswald Mosley and his recently formed New Party. He edited the party newspaper, Action, and stood unsuccessfully for Parliament in the 1931 General Election. Nicolson ceased to support Mosley when he formed the British Union of Fascists in 1932.

Nicolson entered the House of Commons as National Labour MP for West Leicester in the 1935 General Election. Nicolson served as Parliamentary Secretary to the Ministry of Information in the coalition government formed by Winston Churchill in 1940. Nicolson was defeated in the 1945 General Election.

Books written by Nicolson include: Peacemaking 1919 (1933), Curzon (1934), The Congress of Vienna (1946), King George V (1952), Good Behaviour (1956), The Age of Reason (1961) and Kings, Courts and Monarchy. His Diaries and Letters (1968), edited by his son, Nigel Nicolson, provide an interesting insight into political life between the two world wars. Harold Nicolson died on 1st May 1968, following a stroke, and was buried at Sissinghurst Church.

On this day in 1897 Mollie Steimer, was born in Dunaevtsky, Russia. When she was fifteen her family emigrated to the United States and settled in New York City. Steimer found work in a garment factory and soon became involved in trade union activities. This led to her reading books on politics including Women and Socialism (August Bebel), Statehood and Anarchy (Mikhail Bakunin), Memoirs of a Revolutionist (Peter Kropotkin) and Anarchism and Other Essays (Emma Goldman).

In 1917 Steimer joined the Freiheit, a group of Jewish anarchists based in New York City, that had been formed by Johann Most. Steimer shared a six-room apartment at 5 East 104th Street in Harlem with members of the group. This also became the place where the Freiheit held its meetings and published its newspaper. Other members included Emma Goldman and Alexander Berkman. Some of the younger members, including Steimer, formed a new group called Frayhayt (Freedom) and launched a new journal with the same name. She persuaded Robert Minor to produce some cartoons for the journal.

The Frayhayt group were opposed to the United States becoming involved in the First World War. On the masthead of their newspaper contained the words: "The only just war is the social revolution". After the USA declared war on the Central Powers in 1917, Congress passed the Espionage Act, making it an offence to publish material that undermined the war effort.

Steimer was furious when she heard the news that the United States Army had invaded Russia after the Bolshevik government signed the Brest-Litovsk Treaty. She produced two leaflets, one in English and one in Yiddish, appealing to American workers to launch a general strike. "Will you allow the Russian Revolution to be crushed? You; yes, we mean you, the people of America! The Russian Revolution calls to the workers of the world for help... Yes, friends, there is only one enemy of the workers of the world and that is capitalism."

An estimated 10,000 leaflets were distributed in New York City before Mollie Steimer, Jacob Abrams, Hyman Lachowsky, Samuel Lipman, Jacob Schwartz and Gabriel Prober were arrested on 23rd August, 1918, for publishing material that undermined the American war effort. The men were beaten in prison and Schwartz died before he could be brought to court. At his funeral, John Reed and Alexander Berkman made speeches to a gathering of 1,200 mourners.

The trial began on 10th October, 1918, at the Federal Court House in New York City. During the proceedings, the 20 year old Steimer explained her anarchist beliefs: "Anarchism is a new social order where no group shall be governed by another group of people. Individual freedom shall prevail in the full sense of the word. Private ownership shall be abolished. Every person shall have an equal opportunity to develop himself well, both mentally and physically. We shall not have to struggle for our daily existence as we do now. No one shall live on the product of others. Every person shall produce as much as he can, and enjoy as much as he needs - receive according to his need. Instead of striving to get money, we shall strive towards education, towards knowledge. While at present the people of the world are divided into various groups, calling themselves nations, while one nation defies another - in most cases considers the others as competitive - we, the workers of the world, shall stretch out our hands towards each other with brotherly love. To the fulfillment of this idea I shall devote all my energy, and, if necessary, render my life for it."

Steimer was found guilty of breaking the Espionage Act and was sentenced to fifteen years and a $500 fine. Jacob Abrams, Hyman Lachowsky and Samuel Lipman got twenty years and a $1,000 fine. Gabriel Prober, who had been arrested by mistake, was cleared of all charges. Zechariah Chafee of the Harvard Law School led the protests against the severity of the sentences. He pointed out had been convicted solely for advocating non-intervention in the affairs of another nation: "After priding ourselves for over a century on being an asylum for the oppressed of all nations, we ought not suddenly jump to the position that we are only an asylum for men who are no more radical than ourselves."

Others who joined in the protests included Felix Frankfurter, Norman Thomas, Roger Baldwin, Margaret Sanger, Lincoln Steffens, Elizabeth Gurley Flynn, Hutchins Hapgood, Leonard Dalton Abbott, Alice Stone Blackwell, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow and Neith Boyce. A group, the League of Amnesty of Political Prisoners was formed and it published a leaflet on the case, Is Opinion a Crime? Steimer and the the other three anarchists were released on bail to await the results of their appeal.

Over the next few months Steimer was arrested seven times but after being held in various prisons was always released without charge. Agnes Smedley was one of those who met her in prison: "Mollie Steimer championed the cause of the prisoners - the one with venereal disease, the mother with diseased babies, the prostitute, the feeble-minded, the burglar, the murderer. To her they were but products of a diseased social system. She did not complain that even the most vicious of them were sentenced to no more than 5 or 7 years, while she herself was facing 15 years in prison."

Emma Goldman complained that: "The entire machinery of the United States government was being employed to crush this slip of a girl weighing less than eighty pounds." On the 30th October, 1919, she was arrested she was taken to Blackwell Island. While in prison the Supreme Court upheld her conviction under the Espionage Act. However, two justices, Louis Brandeis and Oliver Wendell Holmes, issued a strong dissenting opinion. Steimer was now transferred to the Jefferson City Prison in Missouri.

During this period A. Mitchell Palmer, the attorney general and his special assistant, John Edgar Hoover, used the Sedition Act to launch a campaign against radicals and their organizations. Using this legislation it was decided to remove immigrants who had been involved in left-wing politics. This included Steimer, Emma Goldman, Alexander Berkman and 245 other people who were deported to Russia. A fellow anarchist, Marcus Graham, wrote: "In Russia their activity is yet more needed. For there, a government rules masquerading under the name of the proletariat and doing everything imaginable to enslave the proletariat."

Deported to Russia on the Estonia, Steimer arrived in Moscow on 15th December, 1921. Over the next few months she worked closely with Vsevolod Volin, the editor of the Golos Truda, a journal published in Petrograd. She was also a member of the the Nabat Confederation of Anarchist Organizations. The Bolshevik government hated anarchists and she soon became a target for the Russian Secret Police.

On 1st November, 1922 she was arrested with her boyfriend, Senya Fleshin and charged with aiding criminal elements in Russia. Sentenced to two years in Siberia, Steimer managed to escape and return to Moscow where she worked for the Society to Help Anarchist Prisoners. She was soon arrested and on 27th September she was deported to Germany where she joined Emma Goldman and Alexander Berkman in Berlin.

Mollie Steimer began contributing articles for anarchist journals in Europe. In one article published in January 1924 she argued that in Russia, a great popular revolution had been usurped by a ruthless political elite: "No, I am not happy to be out of Russia. I would rather be there helping the workers combat the tyrannical deeds of the hypo-critical Communists."

Steimer and Senya Fleshin moved to Paris and joined a group of anarchist exiles that included Nestor Makhno, Peter Arshinov, Vsevolod Volin, Emma Goldman, Alexander Berkman, Alexander Schapiro, Sébastien Faure, Jacques Doubinsky and Rudolf Rocker. They formed the Joint Committee for the Defense of Revolutionaries Imprisoned in Russia. In 1926 they established the Relief Fund of the International Working Men's Association for Anarchism and Anarcho-Syndicalists Imprisoned in Russia.

Emma Goldman sometimes clashed with Steimer: "Mollie Steimer is a fanatic to the highest degree... She is terribly sectarian, set in her notions, and has an iron will. No ten horses could drag her from anything she is for or against. But with it all she is one of the most genuinely devoted souls living with the fire of our ideal."

In 1926 Nestor Makhno joined forces broke with Peter Arshinov to publish their controversial Organizational Platform, which called for a General Union of Anarchists. This was opposed by Mollie Steimer, Senya Fleshin, Emma Goldman, Vsevolod Volin, Alexander Berkman, Sébastien Faure and Rudolf Rocker, who argued that the idea of a central committee clashed with the basic anarchist principle of local organisation. In November 1927 Steimer wrote: "The entire spirit of the platform is penetrated with the idea that the masses must be politically led during the revolution. There is where the evil starts."

Senya Fleshin took up photography. As Paul Avrich has pointed out: "In order to earn a living, Senya had meanwhile taken up the profession of photography, for which he exhibited a remarkable talent; he became the Nadar of the anarchist movement, with his portraits of Berkman, Volin, and many other comrades, both well known and obscure, as well as a widely reproduced collage of the international anarchist press."

In 1929 Fleshin was invited to work in the studio of Sasha Stone in Berlin. Steimer went with him and they remained there until Adolf Hitler took power. They no longer felt safe in Nazi Germany and they moved back to Paris, where they remained until the Second World War. After the Nazi invasion and the formation of the Vichy government, Steimer and Fleshin decided to go to Mexico. They attempted to persuade Vsevolod Volin to go with them but he refused, claiming he had to stay in France in order to "prepare for the revolution when the war is over."

In Mexico City Steimer and Fleshin operated a successful photographic studio. They retired to Cuernavaca in 1963. As the of Anarchist Portraits (1995) has pointed out: "Fluent in Russian, Yiddish, English, German, French, and Spanish, she corresponded with comrades and kept up with the anarchist press around the world." Mollie Steimer died in her home following a heart-attack on 23rd July, 1980.

On this day in 1910 Helen Craggs is arrested after disrupting a speech by David Lloyd George at the Paragon Theatre, Whitechapel. Helen Craggs, and two friends, had broken into the theatre the previous night and climbed onto the roof "only sustained by a few pieces of chocolate they lay through the whole bitter freezing night". When Lloyd George started his speech Helen charged the platform. She was soon captured by the stewards, but "armed with a super-human strength she tore herself free". Votes for Women reported that the stewards were "absolutely appalling in its brutality. Miss Craggs was practically thrown head foremost down the stone steps."

On this day in 1911 Clara Giveen was sentenced to a week in Holloway Prison after being found guilty of holding the bridle of a policeman's horse at a WSPU protest.

On this day in 1911 the Women's Social and Political Union (WSPU) carried out an "official" window smash along Whitehall and Fleet Street. Under pressure from the WSPU the Liberal government introduced the Conciliation Bill that was designed to conciliate the suffragist movement by giving a limited number of women the vote, according to their property holdings and marital status. According to Lucy Masterman, it was her husband, Charles Masterman, who provided the arguments against the legislation: "He (Churchill) is, in a rather tepid manner, a suffragist (his wife is very keen) and he came down to the Home Office intending to vote for the Bill. Charlie, whose sympathy with the suffragettes is rather on the wane, did not want him to and began to put to him the points against Shackleton's Bill - its undemocratic nature, and especially particular points, such as that 'fallen women' would have the vote but not the mother of a family, and other rhetorical points. Winston began to see the opportunity for a speech on these lines, and as he paced up and down the room, began to roll off long phrases. By the end of the morning he was convinced that he had always been hostile to the Bill and that he had already thought of all these points himself...He snatched at Charlie's arguments against this particular Bill as a wild animal snatches at its food." (9)

Winston Churchill argued in the House of Commons: "The more I study the Bill the more astonished I am that such a large number of respected Members of Parliament should have found it possible to put their names to it. And, most of all, I was astonished that Liberal and Labour Members should have associated themselves with it. It is not merely an undemocratic Bill; it is worse. It is an anti-democratic Bill. It gives an entirely unfair representation to property, as against persons.... Of the 18,000 women voters it is calculated that 90,000 are working women, earning their living. What about the other half? The basic principle of the Bill is to deny votes to those who are upon the whole the best of their sex. We are asked by the Bill to defend the proposition that a spinster of means living in the interest of man-made capital is to have a vote, and the working man's wife is to be denied a vote even if she is a wage-earner and a wife.... What I want to know is how many of the poorest class would be included? Would not charwomen, widows, and others still be disfranchised by receiving Poor Law relief? How many of the propertied voters will be increased by the husband giving a £10 qualification to his wife and five or six daughters?"

Some Liberals such as David Lloyd George, the Chancellor of the Exchequer, who was officially in favour of woman's suffrage, was convinced that the chief effect of the Bill, if it became law, would be to hand more votes to the Conservative Party. During the debate on the Conciliation Bill he stated that justice and political necessity argued against enfranchising women of property but denying the vote to the working class. The following day Asquith announced that in the next session of Parliament he would introduce a Bill to enfranchise the four million men currently excluded from voting and suggested it could be amended to include women. Paul Foot has pointed out that as the Tories were against universal suffrage, the new Bill "smashed the fragile alliance between pro-suffrage Liberals and Tories that had been built on the Conciliation Bill."

Millicent Fawcett, the leader of the National Union of Woman's Suffrage Societies (NUWSS), still believed in the good faith of the Asquith government. However, the WSPU, reacted very differently: "Emmeline and Christabel Pankhurst had invested a good deal of capital in the Conciliation Bill and had prepared themselves for the triumph which a women-only bill would entail. A general reform bill would have deprived them of some, at least, of the glory, for even though it seemed likely to give the vote to far more women, this was incidental to its main purpose."

Christabel Pankhurst wrote in Votes for Women that Lloyd George's proposal to give votes to seven million instead of one million women was, she said, intended "not, as he professes, to secure to women a larger measure of enfranchisement but to prevent women from having the vote at all" because it would be impossible to get the legislation passed by Parliament.

On 21st November, the WSPU carried out an "official" window smash along Whitehall and Fleet Street. This involved the offices of the Daily Mail and the Daily News and the official residences or homes of leading Liberal politicians, H. H. Asquith, David Lloyd George, Winston Churchill, Edward Grey, John Burns and Lewis Harcourt. It was reported that "160 suffragettes were arrested, but all except those charged with window-breaking or assault were discharged."

On this day in 1913 John Boulting was born. Boulting was fascinated with the cinema industry and in 1933 he joined Ace Films, a small film distribution company based in Wardour Street, London. He later described this period of his life as one of "selling bad films to reluctant exhibitors". Two years he found work with an independent film producer. He was also a socialist and a member of the Labour Party where he continued his friendship with Roy Poole, Josh Francis and William Ball.

On the outbreak of the Spanish Civil War it was decided to form a Spanish Medical Aid Committee. In his autobiography, All My Sins Remembered (1964), Peter Spencer, 2nd Viscount Churchill, explained what happened: "A group of us - three well-known medical men, a famous scientist, several trade unionists, and one communist - formed a committee for the purpose of collecting money for medical supplies to be sent to the Spanish Government forces." Boulting and his friend, Roy Poole, decided to volunteer to join this group, whereas Josh Francis and William Ball joined the International Brigades.

The First British Hospital was established by Kenneth Sinclair Loutit at Grañén near Huesca on the Aragon front. Boulting joined the group in January 1937. Other doctors, nurses and ambulance drivers at the hospital included Reginald Saxton, Alex Tudor-Hart, Archie Cochrane, Penny Phelps, Rosaleen Ross, Aileen Palmer, Peter Spencer, Patience Darton, Annie Murray, Julian Bell, Roy Poole, Richard Rees, Nan Green, Lillian Urmston, Thora Silverthorne and Agnes Hodgson.

Boulting was involved in the offences at Brunete and Belchite. His friend and fellow ambulance driver, Roy Poole, told the Reading Chronicle: "It's jolly hard work of course. Often you don't get more than five hours to your night. We have had as many as 150 cases to handle in a day. I reckon that I alone have driven my ambulance over 11,000 miles on truly villainous roads - not bad going in about three months. Before we arrived on the scene the wounded had to be dragged down from the mountains on mules."

On his return to England in November 1937 John and his brother Roy Boulting formed Charter Films. Their first film, was the documentary The Ripe Earth. With Roy directing and John producing, the company also put thrillers such as The Landlady (1938), Consider your Verdict (1938), Inquest (1939) and Trunk Crime (1939).

In 1940 John Boulding produced and co-wrote the anti-Nazi film, Pastor Hall. The story was based on the resistance of Pastor Martin Niemöller, played by Wilfred Lawson, who in 1933 had complained about the decision by Adolf Hitler to appoint Ludwig Muller, as the country's Reich Bishop of the Protestant Church. With the support of Karl Barth, a professor of theology at Bonn University, in May, 1934, a group of rebel pastors formed what became known as the Confessional Church. When the Nazi government continued with this policy Niemöller joined with Dietrich Bonhoffer to form the Pastors' Emergency League and published a major document opposing the religious policies of Hitler. As a result, both men were sent to concentration camps. Niemöller went to Dachau and Bonhoffer was sent to Buchenwald where he was executed in 1945.

After making this film John went into the Royal Air Force as a flight mechanic and Roy into the Royal Armoured Corps as a trooper. Later the twin brothers were transferred to their respective service film units, where they made wartime documentaries. They were granted special leave to return to Charter Films and produced the propaganda film The Dawn Guard (1941) for the Ministry of Information and the feature film Thunder Rock (1942). Promoted to the rank of flight lieutenant John Boulting directed the feature-length drama documentary Journey Together (1945).

Alan G. Burton has argued: "The Boultings' wartime cinema was progressive, moralistic, and strongly anti-fascist, with their films promoting the democratic ideals of the people's war and rejecting the discredited appeasement policy of the 1930s. Their achievements were widely recognized and they became identified with the renaissance in British cinema, which was felt to have attained a new maturity and honesty in confronting the national crisis."

After the war John Boulting directed the highly acclaimed Brighton Rock (1947), a film based on the novel by Graham Greene. He then produced Fame Is the Spur (1947), a film based on a novel by Howard Spring that deals with a left-wing politician who betrays his socialist beliefs. This was followed by producing The Guinea Pig (1948) and directing Seven Days to Noon (1950), a film about the possibility of nuclear war.

Boulting then changed direction and made a series of satirical comedy films such as Private's Progress (1956), Lucky Jim (1957), Brothers in Law (1957), Carlton-Browne of the F.O. (1959), I'm All Right Jack (1959), Heavens Above! (1963), The Family Way (1966) and There's a Girl in My Soup (1970). These films helped to make stars of Ian Carmichael, Richard Attenborough, Terry-Thomas and Peter Sellers. John Boulting died on 17th June 1985.

On this day in 1916 Vladimir Purishkevich, the leader of the monarchists in the Duma, wrote to Felix Yusupov proposing the murder of Grigori Rasputin. "I'm terribly busy working on a plan to eliminate Rasputin. That is simply essential now, since otherwise everything will be finished... You too must take part in it. Dmitri Pavlovich Romanov knows all about it and is helping. It will take place in the middle of December, when Dmitri comes back... Not a word to anyone about what I've written."

Yusupov replied the following day: "Many thanks for your mad letter. I could not understand half of it, but I can see that you are preparing for some wild action.... My chief objection is that you have decided upon everything without consulting me... I can see by your letter that you are wildly enthusiastic, and ready to climb up walls... Don't you dare do anything without me, or I shall not come at all!"

Eventually, Vladimir Purishkevich and Felix Yusupov agreed to work together to kill Rasputin. Three other men Grand Duke Dmitri Pavlovich Romanov, Dr. Stanislaus de Lazovert and Lieutenant Sergei Mikhailovich Sukhotin, an officer in the Preobrazhensky Regiment, joined the plot. Lazovert was responsible for providing the cyanide for the wine and the cakes. He was also asked to arrange for the disposal of the body.

Yusupov later admitted in Lost Splendor (1953) that on 29th December, 1916, Rasputin was invited to his home: "The bell rang, announcing the arrival of Dmitri Pavlovich Romanov and my other friends. I showed them into the dining room and they stood for a little while, silently examining the spot where Rasputin was to meet his end. I took from the ebony cabinet a box containing the poison and laid it on the table. Dr Lazovert put on rubber gloves and ground the cyanide of potassium crystals to powder. Then, lifting the top of each cake, he sprinkled the inside with a dose of poison, which, according to him, was sufficient to kill several men instantly. There was an impressive silence. We all followed the doctor's movements with emotion. There remained the glasses into which cyanide was to be poured. It was decided to do this at the last moment so that the poison should not evaporate and lose its potency."

Vladimir Purishkevich supported this story in his book, The Murder of Rasputin (1918): "We sat down at the round tea table and Yusupov invited us to drink a glass of tea and to try the cakes before they had been doctored. The quarter of an hour which we spent at the table seemed like an eternity to me.... Yusupov gave Dr Lazovert several pieces of the potassium cyanide and he put on the gloves which Yusupov had procured and began to grate poison into a plate with a knife. Then picking out all the cakes with pink cream (there were only two varieties, pink and chocolate), he lifted off the top halves and put a good quantity of poison in each one, and then replaced the tops to make them look right. When the pink cakes were ready, we placed them on the plates with the brown chocolate ones. Then, we cut up two of the pink ones and, making them look as if they had been bitten into, we put these on different plates around the table."

Lazovert now went out to collect Rasputin in his car on the evening of 29th December, 1916. While the other four men waited at the home of Yusupov. According to Lazovert: "At midnight the associates of the Prince concealed themselves while I entered the car and drove to the home of the monk. He admitted me in person. Rasputin was in a gay mood. We drove rapidly to the home of the Prince and descended to the library, lighted only by a blazing log in the huge chimney-place. A small table was spread with cakes and rare wines - three kinds of the wine were poisoned and so were the cakes. The monk threw himself into a chair, his humour expanding with the warmth of the room. He told of his successes, his plots, of the imminent success of the German arms and that the Kaiser would soon be seen in Petrograd. At a proper moment he was offered the wine and the cakes. He drank the wine and devoured the cakes. Hours slipped by, but there was no sign that the poison had taken effect. The monk was even merrier than before. We were seized with an insane dread that this man was inviolable, that he was superhuman, that he couldn't be killed. It was a frightful sensation. He glared at us with his black, black eyes as though he read our minds and would fool us."

Vladimir Purishkevich later recalled that Felix Yusupov joined them upstairs and exclaimed: "It is impossible. Just imagine, he drank two glasses filled with poison, ate several pink cakes and, as you can see, nothing has happened, absolutely nothing, and that was at least fifteen minutes ago! I cannot think what we can do... He is now sitting gloomily on the divan and the only effect that I can see of the poison is that he is constantly belching and that he dribbles a bit. Gentlemen, what do you advise that I do?" Eventually it was decided that Yusupov should go down and shoot Rasputin.

Yusupov later recalled : "I looked at my victim with dread, as he stood before me, quiet and trusting.... Rasputin stood before me motionless, his head bent and his eyes on the crucifix. I slowly raised the crucifix. I slowly raised the revolver. Where should I aim, at the temple or at the heart? A shudder swept over me; my arm grew rigid, I aimed at his heart and pulled the trigger. Rasputin gave a wild scream and crumpled up on the bearskin. For a moment I was appalled to discover how easy it was to kill a man. A flick of a finger and what had been a living, breathing man only a second before, now lay on the floor like a broken doll."

Stanislaus de Lazovert agrees with this account except that he was uncertain who fired the shot: "With a frightful scream Rasputin whirled and fell, face down, on the floor. The others came bounding over to him and stood over his prostrate, writhing body. We left the room to let him die alone, and to plan for his removal and obliteration. Suddenly we heard a strange and unearthly sound behind the huge door that led into the library. The door was slowly pushed open, and there was Rasputin on his hands and knees, the bloody froth gushing from his mouth, his terrible eyes bulging from their sockets. With an amazing strength he sprang toward the door that led into the gardens, wrenched it open and passed out." Lazovert added that it was Vladimir Purishkevich who fired the next shot: "As he seemed to be disappearing in the darkness, Purishkevich, who had been standing by, reached over and picked up an American-made automatic revolver and fired two shots swiftly into his retreating figure. We heard him fall with a groan, and later when we approached the body he was very still and cold and - dead."

Felix Yusupov added: "Rasputin lay on his back. His features twitched in nervous spasms; his hands were clenched, his eyes closed. A bloodstain was spreading on his silk blouse. A few minutes later all movement ceased. We bent over his body to examine it. The doctor declared that the bullet had struck him in the region of the heart. There was no possibility of doubt: Rasputin was dead. We turned off the light and went up to my room, after locking the basement door."

The Grand Duke Dmitri Pavlovich Romanov drove the men to Varshavsky Rail Terminal where they burned Rasputin's clothes. "It was very late and the grand duke evidently feared that great speed would attract the suspicion of the police." They also collected weights and chains and returned to Yusupov's home. At 4.50 a.m. Romanov drove the men and Rasputin's body to Petrovskii Bridge. that crossed towards Krestovsky Island. According to Vladimir Purishkevich: "We dragged Rasputin's corpse into the grand duke's car." Purishkevich claimed he drove very slowly: "It was very late and the grand duke evidently feared that great speed would attract the suspicion of the police." (121) Stanislaus de Lazovert takes up the story when they arrived at Petrovskii: "We bundled him up in a sheet and carried him to the river's edge. Ice had formed, but we broke it and threw him in. The next day search was made for Rasputin, but no trace was found."

The following day the Tsarina Alexandra Fedorovna wrote to her husband about the disappearance of Grigori Rasputin: "We are sitting here together - can you imagine our feelings - our friend has disappeared. Felix Yusupov pretends he never came to the house and never asked him." The next day she wrote: "No trace yet... the police are continuing the search... I fear that these two wretched boys (Felix Yusupov and Dmitri Romanov) have committed a frightful crime but have not yet lost all hope."

On this day in 1927 Rayna Prohme died.of encephalitis (inflammation of the brain).

Inspired by the events of the Russian Revolution, Rayna joined the American Communist Party. After her marriage to William Prohme, they moved to China. In an article published in May 1924, Prohme wrote: "I am going to stay five years in China. I want to see for myself what happens to a people when their friendly familiar world suddenly becomes strange and bewildering. When their age-old social customs are being overthrown, when their religions are being challenged, their houses, their cities, their language, their clothes, their very thoughts are being transformed. I want to see what happens to them - and help, if I can, in the task of keeping the new forces under control, of preventing the changes from coming too fast's."

Rayna and her husband became supporters of the Kuomintang (National People's Party) led by Sun Yat-sen. They edited the Kuomintang’s English-language newspaper in Wuhan. They both associated with Mikhail Borodin, who had been sent to China by Lenin in September 1923. Henry Misselwitz, who worked for the New York Times, admitted that he had to go through Prohme to reach Borodin: "Naturally I wanted to see him (Borodin) in Hankow. The appointment was arranged by Rayna Prohme, a dynamicyoung woman from Chicago, then editing The People's Tribune, organ of the Red rule. She was the wife of William Prohme, another journalist of rare intelligence who at that time was head of the nationalist News Agency - a propaganda organization in Shanghai."

In 1926 Rayna met the journalist, Vincent Sheean. A mutual friend had described her as a "red-headed gal... who spit fire, mad as a hatter, a complete Bolshevik." Sheean was immediately taken by her: "She was slight, not very tall, with short red-gold hair and a frivolous turned-up nose. Her eyes could actually change colour with the changes of light, or even with changes of mood. Her voice, fresh, cool and very American, sounded as if it had secret rivulets of laughter running underneath it all the time, ready to come to the surface without warning... I had never heard anybody laugh as she did - it was the gayest, most unself-conscious sound in the world. You might have thought that it did not come from a person at all, but from some impulse of gaiety in the air."

Rayna and Sheean went to Moscow together. Rayna wanted to study at the Lenin Institute "to be trained as a revolutionary instrument". Sheean was against the idea arguing that Marxism was "a false cloud". According to Sally J. Taylor, the author of Stalin's Apologist: Walter Duranty (1990): "They took rooms together, arguing late into the night about her decision. But she found the debates tiring, and often had trouble getting out of bed the following morning."

While on a visit to the apartment of Dorothy Thompson, another journalist based in the Soviet Union, Rayna fainted. She soon became extremely ill and Sheean's friend, Walter Duranty, arranged for her to be seen by a local doctor. Rayna told Sheean: "The doctor thinks I am losing my mind and that is the worst thing of all. He won't say so, but that is what he thinks. I can tell by the way he holds matches in front of my eyes and tests my responses. He doesn't think I can focus on anything."

Vincent Sheean and Anna Louise Strong attempted to look after Rayna Prohme. He later wrote to Helen Freeland: "About Anna Louise (and this is strictly between us): she is a fine woman, but overpowering isn't the word for it. Nervous energy, physical strength, etc., etc., and a quite unbridled enthusiasm for every Communist fact or fancy. She nearly drove Rayna to distraction during that last week. This in spite of the fact that Anna Louise was overwhelmingly kind, efficient, and good. It was something Rayna couldn't help. She used to say to me: 'For God's sake get Anna Louise out and keep her out; I cannot bear having her in the room'. I did so as much as possible, but of course Anna Louise was very much there most of the time, or large parts of the time. For God's sake don't repeat this; I've told nobody but Bill about it; it seems rather hard on Anna Louise, who really meant so well and did so much; but the unfortunate woman has such a blustery character that one can't bear being with her much. I shared to the full Rayna's feeling about her, and was ashamed of feeling that way (as was Rayna)."

On 9th November, 1927, Rayna wrote to her husband, William Prohme, who was still in China: "I am doing very little work, but things are falling into place a little bit. It has been so completely disorganized so far and I have been laboring under this wretched cloud of headache and foggy mind. My mind is queer, Beanie, sometimes I think actually not right. Do you suppose I could be getting dementia praecox or some other mental disease? Else why should I have these maddening lapses of memory? I can't make it out.... I am getting books and in spare minutes I am going to try to make the mind work again. Whether it will or not, I don't know. I feel that it is ageing - on the downgrade. You will think that foolish of me, but really Beanie, I am not as young as I once was, in looks, brain, spirit, anything. I have a feeling of definite age when I am with very young people - 20 and 21, or even more. It comes on me all of a sudden. I never felt that before."

Vincent Sheean recalled in his autobiography, Personal History (1933): "She had spoken vaguely of the fear before, and all I could do was say that I did not believe it was well founded. But on the next day she felt certain that this was the case, and it kept her silent and almost afraid to speak, even to me. I sat beside her hour after hour in the dark, silent room, and blackness pressed down and in upon us." Sheean said that two or three times she raised her voice to say: "Don't tell anybody".

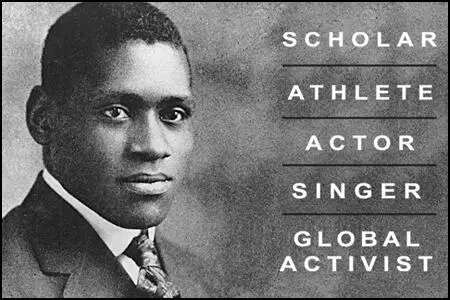

On this day in 1929 Paul Robeson, a member of the National Association for the Advancement of Coloured People (NAACP), talked about the connections between slavery and music. "The African people have an almost instinctive flair for music. This faculty was born in sorrow. I think that slavery, its anguish and separation - and all the longings it brought - gave it birth. The nearest to it is to be found in Russia, and you know about their serf sorrows. The Russian has the same rhythmic quality - but not the melodic beauty of the African. It is an emotional product, developed, I think, through suffering."

On this day in 1979 Anthony Blunt admits to being a Soviet spy. In January 1934 Arnold Deutsch, one of NKVD's agents, was sent to London. As a cover for his spying activities he did post-graduate work at London University. In May he made contact with Litzi Friedmann and Edith Tudor Hart. They discussed the recruitment of Soviet spies. Litzi suggested her husband, Kim Philby. "According to her report on Philby's file, through her own contacts with the Austrian underground Tudor Hart ran a swift check and, when this proved positive, Deutsch immediately recommended... that he pre-empt the standard operating procedure by authorizing a preliminary personal sounding out of Philby."

Deutsch asked Philby if he was willing to spy for the Soviet Union: "Otto spoke at great length, arguing that a person with my family background and possibilities could do far more for Communism than the run-of-the-mill Party member or sympathiser... I accepted. His first instructions were that both Lizzy and I should break off as quickly as possible all personal contact with our Communist friends." It is claimed by Christopher Andrew, the author of The Defence of the Realm: The Authorized History of MI5 (2009) that Philby became the first of "the ablest group of British agents ever recruited by a foreign intelligence service."

Arnold Deutsch asked Kim Philby to make a list of potential recruits. The first person he approached was his friend, Donald Maclean, who had been a fellow member of the Cambridge University Socialist Society (CUSS) and now working in the Foreign Office. Philby invited him to dinner, and hinted that there was important clandestine work to be done on behalf of the Soviet Union. He told him that "the people I could introduce you to are very serious." Maclean agreed to met Deutsch. He was told to carry a book with a bright yellow cover into a particular café at a certain time. Deutsch was impressed with Maclean who he described as being "very serious and aloof" with "good connections". Maclean was given the codename "Orphan". Maclean was also ordered to give up his communist friends.

In May 1934 Philby arranged for Deutsch to meet Guy Burgess. At first Deutsch rejected Burgess as a potential spy. He reported to headquarters that Burgess was "very smart... but a bit superficial and could let slip in some circumstances." Burgess began to suspect that his friend Maclean was working for the Soviets. He told Maclean: "Do you think that I believe for even one jot that you have stopped being a communist? You're simply up to something." (15) When Maclean told Deutsch about the conversation, he reluctantly signed him up. Burgess went around telling anyone who would listen that he had swapped Karl Marx for Benito Mussolini and was now a devotee of Italian fascism. (16) Burgess along with Philby joined the also joined the Anglo-German Fellowship, a pro-fascist society formed in 1935 to foster closer understanding with Adolf Hitler.

Guy Burgess now suggested the recruitment of one of his friends, Anthony Blunt. Later, he claimed that he could not remember the date when he became a Soviet spy. John Costello, the author of Mask of Treachery (1988), has carried out a special study of the subject: "Since the consensus of American intelligence opinion is that the actual closing would have taken place outside England, it is likely to have occurred in the spring of 1934, when Blunt was traveling through France and Austria en route to Italy."

In 1944 Blunt was responsible for liaison between MI5 and Allied Supreme Headquarters concerning the invasion of Europe. Blunt became involved in what became known as the Double-Cross System. Created by John Masterman, it attempted to "influence enemy plans by the answers sent to the enemy (by the double agents)" and to "deceive the enemy about our plans and intentions". (26) Blunt also played a part in the deception plans for the D-Day landings. The key aims of the deception were: "(a) To induce the German Command to believe that the main assault and follow up will be in or east of the Pas de Calais area, thereby encouraging the enemy to maintain or increase the strength of his air and ground forces and his fortifications there at the expense of other areas, particularly of the Caen area in Normandy. (b) To keep the enemy in doubt as to the date and time of the actual assault. (c) During and after the main assault, to contain the largest possible German land and air forces in or east of the Pas de Calais for at least fourteen days."

John Costello, the author of Mask of Treachery (1988) has explained that Blunt worked with Tomás Harris and Juan Pujol García (Garbo) in this operation: "To reinforce this deception, Blunt and Harris had Garbo invent a subsidiary agent who supposedly operated in the Dover area. This agent was a disaffected Welsh nationalist seaman, code-named Donny. He provided a steady stream of sightings of American and Canadian troops assembling in the vicinity of England's principal channel port. His reports continued even after Allied troops had landed on the Normandy beaches on June 6, 1944. This contributed to the German High Command's decision to recall divisions already on their way south, in anticipation of a second and bigger operation taking place in the Pas de Calais."

At the end of the war Anthony Blunt went on a secret mission for the Royal family. According to Hugh Trevor-Roper, Blunt had been sent to retrieve documents that were believed to be in the hands of the royal family's many German relations. It was feared that the contents of these letters would be published in American newspapers. Blunt told Trevor-Roper that his mission had been successful and gave him some of the details of what was in the letters. It was clear that Blunt had made himself familiar with the contents of these papers.

It has been claimed that these documents included letters from the Duke of Windsor to Adolf Hitler. It has even been suggested that there was evidence in these documents that Windsor might have provided information about Britain's war plans: "This plan required the British Expeditionary Force (BEF) to advance northward in the event of a German invasion of Belgium... The Ardennes was precisely the sector where General Guderian's XIX Panzer Group burst through on May 10, when Hitler unleashed his offensive in the West. This fact raises the possibility of a connection between the Duke of Windsor's activities at Allied GCHQ and the German decision of February 1940 to scrap their original attack plan in favor of a bold drive through the Ardennes to the Belgian coast so as to cut off the British forces."

These documents also showed that Windsor was close to breaking with his brother, King George VI, and moving to Nazi Germany. However, according to a telegram from Eberhard von Stohrer to Berlin, Windsor changed his mind the British media would "let loose upon himself the propaganda of his British enemies which would rob him of all prestige for the moment of possible intervention". Donald Cameron Watt, who has examined the Duke of Windsor section of the German Foreign Ministry files and says that important documents that refer to the Windsors' meeting with Hitler at Berchtesgaden are missing.

A few months later Blunt retired from MI5 to become Surveyor of the King's Pictures. This seemed to be a strange decision as it now meant that he could no longer be much use to his Soviet masters. Blunt later argued that "from 1945 I ceased to pass information to the Russians". The reason he gave was that he began to doubt that the Soviet regime "was following the true principles of Marxism." John Costello has argued that the Soviets would only have sanctioned Blunt's move from MI5 only if two conditions were satisfied: "(i) Moscow already had in MI5 another agent - or agents - of equivalent seniority and access. (ii) Blunt convinced Moscow that he would continue providing high-level intelligence about the British government."

Blunt's role as a Soviet agent was exposed in Andrew Boyle's book, The Climate of Treason in 1979. This resulted in his knighthood, awarded in 1956, being annulled. Margaret Thatcher told the House of Commons that: "It was considered important to gain Blunt's cooperation in the continuing investigations by the security authorities, following the defections of Burgess, Maclean and Philby, into Soviet penetration of the security and intelligence services and other public services during and after the war. Accordingly the Attorney-General authorized the offer of immunity to Blunt if he confessed. The Queen's Private Secretary was informed both of Blunt's confession and of the immunity from prosecution, on the basis of which it had been made. Blunt was not required to resign his appointment in the Royal Household, which was unpaid. It carried with it no access to classified information and no risk to security and the security authorities thought it desirable not to put at risk his cooperation."