On this day on 17th November

On this day in 1558 Queen Mary I of England died. At the time Mary became Queen she was thirty-seven, small in stature and near-sighted, appeared older than her years and often tired, because of her generally poor health. Her first parliament reinforced the Act of Succession of 1543 by declaring the validity of the marriage of her mother, Catherine of Aragon, so that the issue of "Mary's legitimacy could not be associated with the abolition of the royal supremacy and the restoration of papal authority."

Almost from her infancy Mary had "hawked around Europe and offered to every prince from Portugal to Poland". As she had been described by her own father as illegitimate, she did not obtain a husband. She felt humiliated and now she was Queen of England, she had much more to offer. Mary also needed an heir. The Protestant attempts to overthrow Mary had also made her feel insecure. To protect her position, Mary decided to form an alliance with the Catholic monarchy in Spain. This gave her the "prospect of a Catholic heir, reunion with Rome, her martyred mother's Spanish dynasty."

Mary was the first woman to rule England in her own right. It soon became clear that Mary was not going to be ruled by her Privy Council. Her first move was to put her marriage into the hands of her cousin, the Holy Roman Emperor Charles V. Therefore her councillors found that Mary had excluded them from the marital decision-making process. This is something that no previous king had done.

Charles V, with little concern for Mary, seized the opportunity to increase his influence over England by proposing his son Philip II as her husband. According to Simon Renard, the Spanish ambassador, Mary disliked the idea and reached the decision with the greatest reluctance. "She was disgusted at the idea of having sex with a man; but the Emperor and his ambassador were strongly in favour of a marriage which would unite England with the Emperor's territories in a permanent alliance." This move was opposed by Bishop Stephen Gardiner, her Lord Chancellor, who wanted her to marry Edward Courtenay, a man he thought was more acceptable to the English people.

Mary was determined to produce an heir, thus preventing her sister, Elizabeth, a Protestant, from succeeding to the throne. In negotiations it was agreed that Philip was to be styled "King of England", but he could not act without his wife's consent or appoint foreigners to office in England. Philip was unhappy at the conditions imposed, but he was ready to agree for the sake of securing the marriage.

In the summer of 1558 Mary began to get pains in her stomach and thought she was pregnant. This was important to Mary as she wanted to ensure that a Catholic monarchy would continue after her death. It was not to be. Mary had stomach cancer. Mary now had to consider the possibility of naming Elizabeth as her successor. "Mary postponed the inevitable naming of her half-sister until the last minute. Although their relations were not always overtly hostile, Mary had long disliked and distrusted Elizabeth. She had resented her at first as the child of her own mother's supplanter, more recently as her increasingly likely successor. She took exception both to Elizabeth's religion and to her personal popularity, and the fact that first Wyatt's and then Dudley's risings aimed to install the princess in her place did not make Mary love her any more. But although she was several times pressed to send Elizabeth to the block, Mary held back, perhaps dissuaded by considerations of her half-sister's popularity, compounded by her own childlessness, perhaps by instincts of mercy." On 6th November she acknowledged Elizabeth as her heir.

On this day in 1792 social reformer Archibald Prentice was born in Lanarkshire. After a brief period at school, Archibald Prentice started work at a warehouse clerk for Thomas Grahame, a local textile manufacture. Prentice impressed his employer and in 1815 Grahame sent him to represent the business in Manchester.

Over the next few years Prentice became friends with local social reformers such as John Edward Taylor, John Shuttleworth, Absalom Watkin, Joseph Brotherton, William Cowdray, Thomas Potter and Richard Potter. The group was strongly influenced by the ideas of Jeremy Bentham and Joseph Priestley. Prentice described Bentham's writings as "my political text books".

Archibald Prentice, like the rest of the businessmen in Manchester, objected to a system that denied important industrial towns and cities representation in the House of Commons. The men met in the back room of John Potter's house which became known as Potter's Planning Parlour.

On 16th August, 1819, Prentice observed the beginning of the reform meeting at St Peter's Field from the window of a friend's house in Mosley Street. Prentice had left the area when the attack on the crowd took place. However, after interviewing several people who had seen what had happened, Prentice wrote an account of the event and sent it to a London newspaper. The story left Manchester by night coach and appeared in the London newspaper 48 hours later. This article, along with the report that John Edward Taylor wrote for The Times, ensured that the events at St. Peter's Field became national news.

After the Peterloo Massacre Archibald Prentice became a regular contributor to local newspapers. This included the Manchester Guardian, the newspaper founded by John Edward Taylor in 1821. However, Prentice did not believe the Manchester Guardian was radical enough and in 1824 he purchased his own newspaper, the Manchester Gazette.

Prentice was a great supporter of Jeremy Bentham and in 1825 wrote in his newspaper: "Believing that the great object of legislation and government ought to be to produce the greatest happiness to the greatest number, we shall, in all our political discussions, keep that object before us." Prentice edited the Manchester Gazette until 1828 when his bankruptcy forced him to close the newspaper. Later that year his radical friends put up the money for a newspaper that he called the Manchester Times.

In his newspapers, Archibald Prentice advocated parliamentary reform, religious toleration and free trade. By 1830 the Manchester Times was selling well over 3,000 copies per week. This was more than the Manchester Guardian but John Edward Taylor was more successful in persuading people to advertise in his newspaper. After 1830 sales of the Manchester Times declined. People objected to his "schoolmaster tone" and unlike Taylor's Manchester Guardian, Prentice was unwilling to include many stories on non-political issues.

In 1835 Archibald Prentice joined Joseph Hume and Francis Place to form the Anti-Corn Law Association. Three years later Prentice organised a meeting in Manchester to protest against the Corn Laws. Only six people turned up but it was decided to form the Anti-Corn Law League. Soon afterwards John Bright and Richard Cobden joined the organisation.

The sales of the Manchester Times remained poor and when a a rival radical newspaper, the Manchester Examiner, appeared in 1846, Archibald Prentice found he could no longer make a profit from the venture. In 1847 Prentice agreed to sell his business to the owners of the Manchester Examiner.

After leaving newspaper publishing, Archibald Prentice found work at the Manchester Gas Office. However, he continued to write and had several books published including: Tour of the United States (1848), Historical Sketches and Personal Reminiscences of Manchester (1851) and History of the Anti-Corn Law League (1853). Archibald Prentice died on 24th December, 1857.

On this day in 1878 Grace Abbott, the sister of Edith Abbott, was born in Grand Island, Nebraska. Both sisters were influenced by their mother's passionate belief in equal rights for women. After graduating from college she worked as a school teacher in Grand Island while continuing her studies at the University of Nebraska.

In 1907 Abbott moved to Chicago where she became a resident of Hull House and joined other women interested in social reformer such as Jane Addams, Ellen Gates Starr, Mary McDowell, Mary Kenney, Edith Abbott, Alzina Stevens, Florence Kelley, Julia Lathrop, Alice Hamilton and Sophonisba Breckinridge.

Abbott joined with Sophonisba Breckinridge to establish the Immigrants' Protective League (IPL). As well as being director of IPL she taught at the University of Chicago (1910-17). Abbott wrote a series of articles about the way immigrants were exploited for the Chicago Evening Post (1909-10). A book on the subject, The Immigrant and the Community, was published in 1917.

In 1917 Woodrow Wilson appointed Abbott as director of the child-labour division of the United States Children's Bureau. After the Keating-Owen Act was declared unconstitutional in 1918, Abbott resigned and became director of Illinois State Immigrants Commission.

Abbott replaced Julia Lathrop as head of the Children's Bureau in 1921. However, her work was handicapped by the Sheppard-Towner Act being declared unconstitutional in 1922. During this period Abbott was a member of the Advisory Committee on Traffic in Women and Children (1922-34) that had been established by the League of Nations.

In 1934 Abbott became professor of public welfare at the University of Chicago and was involved in helping Franklin D. Roosevelt draft the Social Security Act (1935). This legislation that set up a national system of old age pensions and co-ordinated federal and state action for the relief of the unemployed.

Abbott was also editor of the Social Service Review (1934-39) and the author of The Child and the State (1938). Grace Abbott died in Chicago on 19th June, 1939. From Relief to Social Security (1941) was published posthumously.

On this day in 1894 Syd Puddefoot was born in Bow. He was educated at Park School in West Ham and played football for Limehouse Town. Puddefoot was signed by West Ham United manager, Syd King, after he saw him play for London Juniors against Surrey Juniors in 1912.

Puddefoot, a centre-forward, joined a team that already included two outstanding strikers in Danny Shea and George Hilsdon. However, he soon won a place in the starting line-up and scored his debut goal against Brighton & Hove Albion on 21st March, 1913.

As John Northcutt and Roy Shoesmith point out in their book, West Ham United: An Illustrated History (1994): "The 19-year-old Syd Puddefoot arrived and he found the net on 13 occasions in his first 11 games... He proved he could find the net when opposed by a quality defence, scoring in both games of a replayed cup-tie against Liverpool."

Puddefoot established an FA Cup goal scoring record for the club on 10th January, 1914, when he scored five times in an 8-1 victory over Chesterfield. That season he scored 16 goals in 20 cup and league games. He also developed a good partnership with Richard Leafe who had been purchased from Sheffield United as a replacement for Danny Shea who had been sold to Blackburn Rovers for a British record transfer fee of £2,000.

West Ham United finished in 4th place of the Southern League in the 1914-15 season. Puddefoot was top scorer with 18 goals in 35 league games. This included a hat-trick against Exeter City on 2nd January 1915. The local newspaper reported that: "Some 14 minutes elapsed before Puddefoot, who completely outshone every other forward on the field, opened the scoring for his side and ten minutes later he was again successful in finding the net."

The outbreak of the First World War resulted in the disbandment of the Southern League in 1915. Puddefoot, who was not conscripted into the British Army until late into the conflict, made 126 appearances in the London Combination league. In one game against Crystal Palace he scored seven goals, a record for the competition.

West Ham United finished in 7th place in the 1919-20 season. Puddefoot was once again top scorer with 26 goals in 43 league and cup games. This included hat-tricks against Port Vale, Bury and Nottingham Forest. He continued in good form in the 1920-21 season with 29 goals in 38 league games.

Syd King had managed to build a very good West Ham team that included Jimmy Ruffell, George Kay, Edward Hufton, Jack Tresadern, Vic Watson, Sid Bishop, Richard Leafe, Billy Brown and Jack Young. The team relied heavily on Puddefoot's goals and it was great shock to the fans when King sold him to Falkirk for the British record fee of £5,000 in February 1922. Puddefoot had netted 107 goals in 194 games for the club.

As the authors of the The Essential History of West Ham United (2000) pointed out that his departure "nearly caused a riot among Hammers fans". However, the club blamed Puddefoot in a statement issued after his transfer: "The departure of Syd Puddefoot came as no surprise to those intimately connected with him. It is an old saying that everyone has one chance in life to improve themselves and Syd Puddefoot is doing the right thing for himself in studying his future. We understand that he will be branching out in commercial circles in Falkirk and when his football days are over he will be assured of a nice little competency."

The truth of the matter was that Puddefoot was very reluctant to move to Scotland to play for Falkirk. However, at this time footballers had little control over these matters. At the time of his departure, it looked like West Ham United would win promotion to the First Division. However, without their top goalscorer, the club lost five of their last seven games and finished in 4th place.

Puddefoot was unable to recapture the form he showed at West Ham. He later complained that his Scottish teammates refused to pass to him in games. However, he still managed to score 45 goals for the club.

In February 1925, Blackburn Rovers purchased Puddefoot for a fee of £4,000. As Mike Jackman argued in his book, Blackburn Rovers (2006): "Although aged 30, Puddefoot, who had previously played with West Ham United, was the type of gifted playmaker that the club desperately needed, and following his arrival there was an immediate upturn in results... Puddefoot remained one of the most gifted footballers of his era. His vision and passing ability made him the supreme play-maker, the man who made the bullets for others to fire."

Puddefoot won his first international cap for England against Northern Ireland on 25th October 1925. The game ended in a 0-0 draw. Puddefoot also failed to score in his second game for England against Scotland the following year. His former team-mate Jimmy Ruffell, also played in this game.

Blackburn Rovers had a good FA Cup run in the 1927-28 season. They beat Newcastle United (4-1), Exeter City (3-1), Port Vale (2-1), Manchester United (2-0), Arsenal (1-0) to reach the final against Huddersfield Town at Wembley Stadium.

Huddersfield were hot favourites to win the final. However, in the first minute Jack Roscamp received a pass from Syd Puddefoot. He chipped the ball over the head of Ned Barkas. Billy Mercer, the Huddersfield goalkeeper, attempted to catch the ball. Roscamp collided with Mercer and the ball slipped out of his grasp and trickled into the empty net. Tom McLean added a second after 22 minutes. Alex Jackson got one back for Huddersfield but Roscamp scored his second and Blackburn's third in the 85 minute to give the underdogs a well-deserved victory.

At the age of 37 Syd Puddefoot returned to West Ham United in a vain attempt to prevent West Ham from being relegated from the First Division (1931-32). He retired in 1933 having scored 146 goals in 375 Football League games.

Puddefoot became the coach of Turkish club Fenerbahçe. The following year, he moved to Galatasaray, but as Tony Hogg pointed out in Who's Who of West Ham United (2004): "It proved to be a bad move when he was badly manhandled while trying to calm down fighting players and spectators during a big game. Seventeen players were suspended and Puddy returned to England."

In March 1937 Puddefoot was appointed manager of Northampton Town. He held the post until the outbreak of the Second World War. During the conflict he was employed by the Blackpool Borough Police. Later he worked for the Civil Service at the Ministry of Pensions. He retired to Essex in 1963 and worked as a scout for Southend United. Sydney Puddefoot died in Rochford Hospital from pneumonia on 2nd October, 1972.

On this day in 1916 historian Rodney Hilton was born in Middleton, Manchester. He was brought up in a family of Unitarians active in the Independent Labour Party. Hilton attended Manchester Grammar School and Balliol College, Oxford, where he met Christopher Hill and Denis Healey. A Marxist, Hilton's PhD involved a study of the rural economy of Leicestershire between the 13th and 15th centuries.

During the Second World War Hilton joined the British Army and served in North Africa, Syria, Palestine and Italy. On his return he began teaching at Birmingham University. He stayed at the university for the next 36 years. In 1950 Hilton with Hyman Fagan published the ground-breaking book, The Revolt of 1381. As Christopher Dyer pointed out: "He took medieval peasants seriously, as people with ideas, who were able to organise themselves in purposeful actions... Hilton saw in that rebellion, led by John Ball and Wat Tyler, a coherent programme and lasting effects, both of which were denied by historians who were less sympathetic towards the rebels."

Hilton, a member of the Communist Party of Great Britain, joined E. P. Thompson, Christopher Hill, Eric Hobsbawm, A. L. Morton, Raphael Samuel, George Rudé, John Saville, Dorothy Thompson, Edmund Dell, Victor Kiernan and Maurice Dobb in forming the Communist Party Historians' Group. In 1952 members of the group founded the journal, Past and Present. Over the next few years the journal pioneered the study of working-class history.

Disillusioned by the events in the Soviet Union and the invasion of Hungary, Hilton, like many Marxist historians, left the Communist Party of Great Britain in 1956. Hilton's later books included The English Peasantry in the Later Middle Ages (1975), The Transition From Feudalism to Capitalism (1976), Bond Man Made Free: Medieval Peasant Movements and the English Rising of 1381 (1977), Class Conflict and the Crisis of Capitalism (1985), English and French Towns in Feudal Society: A Comparative Study (1995). Rodney Hilton died on 7th June, 2002.

On this day in 1922 Helena Normanton is the first woman to be called to the bar. Normanton, the daughter of William Normanton, a pianoforte manufacturer, was born in London on 14th December 1882. When Helena was aged four, her father, aged 33, was found dead with a broken neck in a railway tunnel. Her mother, Jane Normanton, moved to Brighton with her two young daughters. She ran a small grocery shop and also turned her family home at 4 Clifton Place into a boarding house.

Normanton was a talented student and in 1896 won a scholarship to York Place Science School (later renamed Margaret Hardy School, forerunner of Varndean School for Girls). She eventually became a pupil teacher but on the death of her mother in 1900 she left school to help run the family boarding house and look after her younger sister. The following year she moved to 11 Hampton Place, Hove, a boarding house owned by her aunt, Eliza Whitehead.

In 1903 Helena became a student at the Edge Hill Teachers' Training College in Liverpool. After qualifying in 1905 she taught history in Glasgow and London. Helena was for a time the private tutor to the sons of Baron Maurice de Forest, the Liberal Party MP for West Ham North. Normanton was a strong supporter of women's suffrage and she joined the Women's Social and Political Union (WSPU).

Members of the WSPU began to question the leadership of Emmeline Pankhurst and Christabel Pankhurst. These women objected to the way that the Pankhursts were making decisions without consulting members. They also felt that a small group of wealthy women like Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence were having too much influence over the organisation. In the autumn of 1907, Normanton, Teresa Billington-Greig, Elizabeth How-Martyn, Dora Marsden, Margaret Nevinson and Charlotte Despard and seventy other members of the WSPU left to form the Women's Freedom League (WFL).

Like the WSPU, the Women's Freedom League was a militant organisation that was willing the break the law. As a result, over 100 of their members were sent to prison after being arrested on demonstrations or refusing to pay taxes. However, members of the WFL was a completely non-violent organisation and opposed the WSPU campaign of vandalism against private and commercial property. The WFL were especially critical of the WSPU arson campaign.

Normanton, like most members of the Women's Freedom League, was a pacifist, and so when the First World War was declared in 1914 the organisation refused to become involved in the British Army's recruitment campaign. The WFL also disagreed with the decision of the NUWSS and WSPU to call off the women's suffrage campaign while the war was on. Leaders of the WFL such as Charlotte Despard believed that the British government did not do enough to bring an end to the war and between 1914-1918 supported the campaign of the Women's Peace Council for a negotiated peace.

As well as campaigning for women's suffrage, Normanton wrote several pamphlets on the issue of women's pay. In Sex Differentiation in Salary (1914) she argued for equal pay for equal work. After the First World War she wrote: "During and after the war, many soldiers' wives and widows became the breadwinners for families. Should they be paid according to their sex or their work?"

In 1918 Normanton applied to be admitted to the Middle Temple. When this application was rejected because she was a woman, she took the case to the House of Lords. However, before the case could be heard, Parliament passed the Disqualification (Removal) Bill. Normanton immediately applied again and therefore became the first woman admitted as a student to the bar. After passing her exams she was called to the bar on 17th November 1922, a few months after Ivy Williams, had become the first woman to do so (but she did not appear in a court of law).

While a student Normanton married Gavin Bowman Clark (1873-1948). As Joanne Workman has pointed out: "Her application to retain her maiden name after her marriage attracted considerable public interest. Helena deplored the loss of a woman's identity on marriage and its disadvantageous legal results. While she believed in the respectability of retaining the title Mrs she also wished to maintain continuity of identity in her professional career." In 1924 she became the first married British woman to be issued a passport in her maiden name.

Normanton gained a great deal of fame "from her writing, public speaking, and feminist activities". This led to claims that she was guilty of advertising her services (forbidden by legal etiquette). In April 1923 she requested the bar council to hold a full inquiry into whether she had ever advertised herself. As this did not happen she curtailed her public speaking engagements and stopped writing for newspapers and magazines.

In 1924 Helena Normanton became the first female counsel in a case at the Old Bailey. The following year she became the first woman to conduct a case in the United States, that established American women's right to retain their maiden names. Despite these achievements her earning from legal work was so low she had to supplement her income by renting rooms in her house in Mecklenburgh Square, Bloomsbury. She also published two books on famous criminal cases, The Trial of Norman Thorne (1929) and The Trial of Alfred Arthur Rouse (1931).

Helena Normanton campaigned for changes in matrimonial law. At the annual meeting of the National Council of Women in October 1934, her proposals were strongly attacked by the Mothers' Union. In 1938 Normanton was co-founder with Vera Brittain, Edith Summerskill and Helen Nutting of the Married Women's Association. The organisation sought equal relationships between men and women in marriage.

Helena Wojtczak remarked in Notable Sussex Women (2008): "In 1948 she became the first woman to lead the prosecution in a murder trial, and the following year became one of the first two women to be appointed King's Counsel. She was an excellent public speaker, wrote articles for various publications and books on a wide variety of subjects, from Shakespeare to buying a house."

In 1952 Helena Normanton made submissions on behalf of the Married Women's Association to the royal commission on marriage and divorce. She proposed that a husband should pay his wife an allowance from the family income. The MWA complained that this suggestion had been submitted to the royal commission "without previous circulation to executive or members". One member complained that her proposal of a housekeeping allowance for wives equated to "pocket money given to a child". As a result of these criticisms, Normanton resigned as president of the MWA.

Normanton was a pacifist and was a member of the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament. She also played a significant role in the campaign for a university in Brighton. In 1956 she made the first donation to the Sussex University appeal. She wrote at the time: "I make this gift in gratitude for all that Brighton did to educate me when I was left an orphan." This was followed by larger donations and she bequeathed the capital of her trust to the university. Helena Normanton died on 14th October, 1957, and is buried at St Wulfran's Churchyard in Ovingdean.

On this day in 1931 William Hewins died. Hewins, the son of Samuel Hewins, an iron-merchant, was born on 11th May 1865. He was educated at Wolverhampton Grammar School and Pembroke College, Oxford. After graduating with a degree in mathematics, Hewins worked as a university extension lecturer.

Sidney Webb and Beatrice Webb met Hewins when they were at the Bodleian Library researching their book on the history of trade unions. When the Webbs founded the London School of Economics (LSE) in 1895 Hewins accepted their offer to became the institution's first director.

Beatrice wrote after his appointment: "Hewins, who expected great things, has been depressed and irritable and it has taken all Sidney's good temper and tact to keep things going smooth. Hewins is a sanguine enthusiast, pulls hard and strong when he feels the stream with him, but I doubt whether he has the staying power for bad times. And he has a small-minded little wife always whispering discontent into his ear, suggesting that he is being put upon and that the enterprise will not succeed."

Hewins held the post until 1903 when he resigned to work for Joseph Chamberlain and his tariff reform campaign. Beatrice Webb recorded in her diary: "Hewins sends in his resignation of the Directorship of the School of Economics. So ends our close relationship with this remarkable man, remarkable for audacity, enterprise, zeal and skill in presenting facts and manipulating persons, most remarkable for confidence in his own powers, more than confidence - an overestimation of them. These qualities have served us well in building up, from nothing, the reputation of the LSE, in steering its fortunes through the indifference and hostility of the London academic and business world, in obtaining and keeping the co-operation of men of diverse views and conflicting interests."

Hewins unsuccessfully contested Shipley (1910) and Middleton (1911) but was elected as the MP for Hereford in May 1912. He supported David Lloyd George during the First World War and when he replaced Herbert Asquith he appointed Hewins as Under-Secretary of State for the Colonies in 1917. According to his biographer, A. C. Howe: "In tandem with his friend Walter Long, a like-minded imperial enthusiast, he undertook much work on trade relations with the empire, and helped organize the 1918 Imperial Conference and develop post-war emigration policy.... Hewins's period in office was, however, brought to an abrupt end, for in 1918 he was not invited to contest Hereford (he believed on religious grounds, others believed because he had neglected to nurse the seat), and he became the only Unionist minister not reappointed by the Lloyd George coalition."

Hewins retired from the House of Commons at the end of the First World War. As well as providing articles for the Encyclopaedia Britannica, Hewins had several books published including Trade in Balance (1924), Empire Restored (1927) and the Apologia of an Imperialist (1929). William Hewins died on 17th November, 1931.

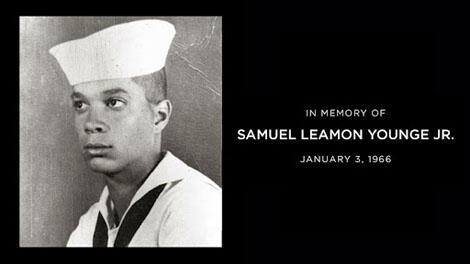

On this day in 1944 Samuel Younge, was born in Tuskegee, Alabama. He became active in the civil rights movement while a student of the Tuskegee Institute.

In the winter of 1966, Younge was working as a vote registration volunteer at the Macon County courthouse. On 3rd January, Younge stopped at a service station to buy some cigarettes and use the toilet. When Younge discovered that African Americans did not use the same facilities as whites, he complained to the owner, Marvin Segrest. During the argument that took place about the Jim Crow facilities, Segrest picked up his gun and shot him dead.

Younge was the fifth civil rights worker who had been killed in Alabama in 12 months. After a protest march organised by students at the Tuskegee Institute, Segrest was arrested and charged with murder. At the end of his trial, an all-white jury found Segrest not guilty of murder.

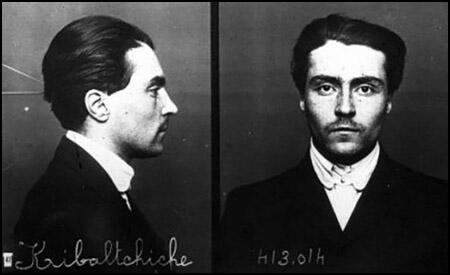

On this day in 1947 historian and revolutionary, Victor Serge, died. Victor Kibalchich (he later took the name Victor Serge), the son of Russian Polish parents, was born in Belgium in 1890. His father, an officer in the Imperial Guard, was a member of the Land and Liberty group and was related to Nikolai Kibalchich of the People's Will. After the arrest of Kibalchich as a result of the assassination of Alexander II in 1881, Serge's father fled the country. He eventually found work as a teacher at the Institute of Anatomy in Brussels.

His father introduced Serge to the writings of Alexander Herzen, Nikolai Chernyshevsky and Vissarion Belinsky: "He (his father) intended to become a physician, but geology, chemistry, sociology, and philosophy also interested him passionately. I never knew him as anything but a man possessed with an insatiable thirst for knowledge and understanding, which was to handicap him during all his remaining years."

Serge wrote in his autobiography, Memoirs of a Revolutionary (1951): "Even before I emerged from childhood, I seem to have experienced, deeply at heart, that paradoxical feeling which was to dominate me all through the first part of my life: that of living in a world without any possible escape, in which there was nothing for it but to fight for an impossible escape. I felt repugnance, mingled with wrath and indignation, towards people whom I saw settled comfortably in this world. How could they not be conscious of their captivity, of their unrighteousness? All this was a result, as I can see today, of my upbringing as the son of revolutionary exiles, tossed into the great cities of the West by the first political hurricanes blowing over Russia."

Victor Serge read a great deal and was influenced by the political theories of Peter Lavrov, Élisée Reclus and Peter Kropotkin. In Brussels in 1906 he became friends with a group of anarchists that included Jean de Boe, Raymond Callemin, Octave Garnier, René Valet and Edouard Carouy. The group became known as the Brussels Revolutionary Gang. He later wrote: "Anarchism swept us away completely because it both demanded everything of us and offered us everything. There was no corner of life that it failed to illumine; at least so it seemed to us...Shot through with contradictions, fragmented into varieties and sub-varieties, anarchism demanded, before anything else, harmony between deeds and words (which, in truth, is demanded by all forms of idealism, but which they all forget as they become complacent)." Serge liked to quote the words of Reclus: "As long as social injustice lasts we shall remain in a state of permanent revolution."

His biographer, Adam Hochschild, has pointed out: "He (Victor Serge) left home while still in his teens, lived in a French mining village, worked as a typesetter, and finally made his way to Paris. There he lived with beggars, read Balzac, and grew fascinated by the underworld. But soon the revolutionary in him overcame the wanderer." Serge became a follower of Albert Libertad. He later recalled in his memoirs: "No one knew his real name, or anything of him before he started preaching. Crippled in both legs, walking on crutches which he plied vigorously in fights (he was a great one for fighting, despite his handicap), he bore, on a powerful body, a bearded head whose face was finely proportioned. Destitute, having come as a tramp from the south, he began his preaching in Montmartre, among libertarian circles and the queues of poor devils waiting for their dole of soup not far from the site of Sacre Coeur. Violent, magnetically attractive, he became the heart and soul of a movement of such exceptional dynamism that it is not entirely dead even at this day. Albert Libertad loved streets, crowds, fights, ideas, and women. On two occasions he set up house with a pair of sisters, the Mahes and then the Morands. He had children whom he refused to register with the State."

In 1909 Victor Serge met Rirette Maitrejean in Lille. He described her as "short, slim, agressive girl, militant, with a Gothic profile". They fell in love and they lived together in Paris. Serge recalled how he worked as "a draughtsman in a machine-tool works, ten hours a day, twelve and a half including the journeys, starting at 6:30 a.m." After the death of Albert Libertad in a street-fight, the couple helped to edit l'Anarchie.

The execution of the non-violent anarchist, Francisco Ferrer in Barcelona on 13th October, 1909, had a profound impact on Serge and his friends. Serge wrote: "His transparent innocence, his educational activity, his courage as an independent thinker, and even his man-in-the-street appearance endeared him infinitely to the whole of a Europe that was, at the time, liberal by sentiment and in intense ferment. A true international consciousness was growing from year to year, step by step with the progress of capitalist civilization.... From one end of the Continent to the other (except in Russia and Turkey) the judicial murder of Ferrer had, within twenty-four hours, moved whole populations to incensed protest."

One of their friends, Liabeuf, a young worker of twenty, armed himself with a revolver and open fire on the police. He wounded four policeman and after being found guilty of attempted murder, was condemned to death. It was decided to execute him at the Boulevard Arago. Serge recalled in Memoirs of a Revolutionary (1951): "I had come with Rirette... The militants from all the groups were there, forced back by walls of black-uniformed police executing bizarre maneuvers. Shouts and angry scuffles broke out when the guillotine wagon arrived, escorted by a squad of cavalry. For some hours there was a battle on the spot, the police charges forcing us ineffectively, because of the darkness, into side streets from which sections of the crowd would disgorge once again the next minute."

Jules Bonnot arrived in Paris in 1911. According to Serge: "From the grapevine we gathered that Bonnot... had been traveling with him by car, had killed him, the Italian having first wounded himself fumbling with a revolver." Bonnot soon formed a gang that included local anarchists, Raymond Callemin, Octave Garnier, René Valet and Edouard Carouy. Serge was totally opposed to what the group intended to do. Callemin visited Serge when he heard what he had been saying: "If you don't want to disappear, be careful about condemning us. Do whatever you like! If you get in my way I'll eliminate you!" Serge replied: "You and your friends are absolutely cracked and absolutely finished."

On 21st December, 1911 the gang robbed a messenger of the Société Générale Bank in broad daylight and then fled in a car. As Peter Sedgwick pointed out: "This was an astounding innovation when policemen were on foot or bicycle. Able to hide, thanks to the sympathies and traditional hospitality of other anarchists, they held off regiments of police, terrorized Paris, and grabbed headlines for half a year."

The police raided the offices of l'Anarchie on 31st December, 1911. Louis Jouin, the vice-chief of the French police, told him: "I know you pretty well; I should be most sorry to cause you any trouble-which could be very serious. You know these circles, these men, who are very unlike you, and would shoot you in the back, basically.... they are all absolutely finished. I can assure you. Stay here for an hour and we'll discuss them. Nobody will ever know anything of it and I guarantee that there'll be no trouble at all for you." Serge refused to help them and they arrested him along with his wife, Rirette Maitrejean. The main evidence consisted of two revolvers found on the premises of the newspaper. They were accused of being part of the Jules Bonnot gang and spent the next fifteen months in solitary confinement.

The gang murdered a police officer at the Place du Havre on 27th February, 1912. The following month, on 25th March, two more people were killed during an attack on the office of the General Corporation in Chantilly. Serge complained in Memoirs of a Revolutionary (1951): "A positive wave of violence and despair began to grow. The outlaw anarchists shot at the police and blew out their own brains. Others, overpowered before they could fire the last bullet into their own heads, went off sneering to the guillotine.... I recognized, in the various newspaper reports, faces I had met or known; I saw the whole of the movement founded by Libertad dragged into the scum of society by a kind of madness; and nobody could do anything about it, least of all myself. The theoreticians, terrified, headed for cover. It was like a collective suicide."

Raymond Callemin was arrested on 7th April, 1912, Seventeen days later, three policemen surprised Jules Bonnot in the apartment of a man known to buy stolen goods. He shot at the officers, killing Louis Jouin, the vice-chief of the French police, and wounding another officer before fleeing over the rooftops. Four days later he was discovered in a house in Choisy-le-Roi. It is claimed the building was surrounded by 500 armed police officers, soldiers and firemen. Bonnot was able to wound three officers before the house before the police used dynamite to demolish the front of the building. In the battle that followed Bonnott was shot ten times. He was moved to the Hotel-Dieu de Paris before dying the following morning. Octave Garnier and René Valet were killed during a police siege of their suburban hideout on 15th May, 1912.

The trial of Maitrejean, Serge, Raymond Callemin, Jean de Boe, Rirette Maitrejean, Edouard Carouy, André Soudy, Eugène Dieudonné and Stephen Monier, began on 3rd February, 1913. According to Serge: "In the course of a month, 300 contradictory witnesses paraded before the bar of the court. The inconsequently of human testimony is astonishing. Only one in ten can record more or less clearly what they have seen with any accuracy, observe, and remember - and then be able to recount it, resist the suggestions of the press and the temptations of his own imagination. People see what they want to see, what the press or the questioning suggest."

Callemin, Soudy, Dieudonné and Monier were sentenced to death. When he heard the judge's verdict, Callemin jumped up and shouted: "Dieudonné is innocent - it's me, me that did the shooting!" Carouy was sentenced to hard labour for life (he committed suicide a few days later). Serge received five years' solitary confinement but Maitrejean was acquitted. Dieudonné was reprieved but Callemin, Soudy and Monier were guillotined at the gates of the prison on 21st April, 1913. Maitrejean married Serge in prison in 1915 in order to have the right to visit and correspond.

Serge was in prison on the outbreak of the First World War. He immediately forecast that the war would lead to a Russian Revolution: "Revolutionaries knew quite well that the autocratic Empire, with its hangmen, its pogroms, its finery, its famines, its Siberian jails and ancient iniquity, could never survive the war." In September, 1914, Serge was in a prison on an island in the Seine, twenty-five miles or so from the Battle of the Marne. The local population, suspecting a French defeat, began to flee, and for a while Serge and the other inmates expected to become German prisoners.

On his release in 1915 he went to live in Spain. He returned to France and after the overthrow of Nicholas II in February, 1917, Serge attempted to get to Russia to join the revolution. He was arrested and imprisoned and held without trial. In October, 1918 the Danish Red Cross intervened and arranged for Serge and other revolutionaries to be exchanged for Bruce Lockhart and other anti-Bolsheviks who had been imprisoned in Russia.

When Serge arrived in Russia in 1919 he joined the Bolsheviks. For a while Serge worked for Maxim Gorky, at the Universal Literature publishing house. Soon afterwards he was employed by Gregory Zinoviev who had been appointed as President of the Executive of the Third International. Serge's knowledge of languages enabled him to organize international editions of the organization's publications. As a former anarchist, Serge had doubts about the Bolshevik government: "Even if there were only one chance in a hundred for the regeneration of the revolution and its workers' democracy, that chance had to be taken."

Serge soon became disillusioned with the Soviet government. He joined with Emma Goldman and Alexander Berkman to complain about the way the Red Army treated the sailors involved in the Kronstadt Uprising. Serge's account of the rebellion was later criticised by Leon Trotsky: "Whether there were any needless victims I do not know. On this score I trust Dzerzhinsky more than his belated critics... Victor Serge's conclusions on this score - from third hand - have no value in my eyes." Serge retorted that his information on Kronstadt came from anarchist eyewitnesses he had interviewed in prison immediately after the rising: "The single fact that Trotsky did not know what all the rank-and-file Communists knew - that out of inhumanity a needless crime had been committed against the proletariat and peasantry - this fact, I repeat, is deeply significant."

A libertarian socialist, Serge protested against the Red Terror that was organized by Felix Dzerzhinsky and the Ckeka. He later recalled: "The telephone became my personal enemy. At every hour it brought me voices of panic-stricken women who spoke of arrest, imminent executions, and injustice, and begged me to intervene at once, for the love of God!"

In 1923 Serge became associated with the Left Opposition group that included Leon Trotsky, Karl Radek, Adolf Joffe, Alexandra Kollontai and Alexander Shlyapnikov. Later Gregory Zinoviev and Lev Kamenev joined in the struggle against Joseph Stalin. Serge was an outspoken critic of the authoritarian way that Joseph Stalin governed the country and is believed to be the first writer to describe the Soviet government as "totalitarian".

In 1928 Serge was arrested and expelled from the Communist Party. He was eventually released while suffering from severe abominable pain. Serge thought he was going to die. He told himself: "If I chance to survive, I must be quick and finish the books I have begun; I must write, write..." Serge's first book, Year One of the Russian Revolution, was finished in 1930. Adam Hochschild has pointed out: "In all his books, and particularly in this one, his masterpiece, his prose has a searing, vivid, telegraphic compactness. Serge's style comes not from endless refinement and rewriting, like Flaubert's, but from the urgency of being a man on the run. The police are at the door; his friends are being arrested; he must get the news out; every word must tell." The book was banned in the Soviet Union. So also were his novels, Men in Prison (1930) and Birth of Our Power (1931). However, they were published in France and Spain.

Serge was arrested and imprisoned in 1933. He was sent to the remote city of Orenburg, in the Ural Mountains. Most of the Left Opposition that were arrested were executed but as a result of protests made by leading politicians in France, Belgium and Spain, Serge was kept alive. The Communist Secret Police (GPU) obtained a confession from his sister-in-law, Anita Russakova, that Serge and her had been involved in a conspiracy led by Leon Trotsky. Serge knew from his contacts in the Communist Party that if he signed the confession he would be executed.

Protests against Serge's imprisonment took place at several International Conferences. The case caused the Soviet government considerable embarrassment and in 1936 Joseph Stalin announced that he was considering releasing Serge from prison. Pierre Laval, the French prime minister, refused to grant Serge an entry permit. Emile Vandervelde, the veteran socialist, and a member of the Belgian government, managed to obtain Serge a visa to live in Belgium. Serge's relatives were not so fortunate: his sister, mother-in-law, sister-in-law (Anita Russakova) and two of his brothers-in-law, died in prison.

On his arrival in France in 1936, Serge resumed work on two books on Soviet communism, From Lenin to Stalin (1937) and Destiny of a Revolution (1937). He also worked closely with a group of supporters of Leon Trotsky that included Lev Sedov, Henricus Sneevliet and Mark Zborowski. Serge also worked on the Bulletin of the Opposition, the journal "which fought against Stalinist reaction for the continuity of Marxism in the Communist International".

After the assassination of Ignaz Reiss, another NKVD agent, Walter Krivitsky discovered that Theodore Maly, who had refused to kill him, was recalled and executed. He now decided to defect to Canada. Once settled abroad he would collaborate with Paul Wohl on the literary projects they had so often discussed. In addition to writing about economic and historical subjects, he would be free to comment on developments in the Soviet Union. Wohl agreed to the proposal. He told Krivitsky that he was an exceptional man with rare intelligence and rare experience. He assured him that there was no doubt that together they could succeed.

Wohl agreed to help Krivitsky defect. To help him disappear he rented a villa for him in Hyères, a small town in France on the Mediterranean Sea. On 6th October, 1937, Wohl arranged for a car to collect Krivitsky, Antonina Porfirieva and their son and to take them to Dijon. From there they took a train to their new hideout on the Côte d'Azur. As soon as he discovered that Krivitsky had fled, Mikhail Shpiegelglass told Nikolai Yezhov what had happened. After he received the report, Yezhov sent back the command to assassinate Krivitsky and his family.

Later that month Walter Krivitsky wrote to Elsa Poretsky and told her what he had done and to express concerns that the NKVD had a spy close to her friend, Henricus Sneevliet. "Dear Elsa, I have broken with the Firm and am here with my family. After a while I will find the way to you, but right now I beg you not to tell anyone, not even your closest friends, who this letter is from... Listen well, Elsa, your life and that of your child are in danger. You must be very careful. Tell Sneevliet that in his immediate vicinity informers are at work, apparently also in Paris among the people with whom he has to deal. He should be very attentive to your and your child's welfare. We both are completely with you in your grief and embrace you." He gave the letter to Gerard Rosenthal, who took it to Sneevliet who passed it onto Poretsky.

Krivitsky also arranged a meeting with Hans Brusse who he hoped to persuade him to defect. Brusse refused declaring that he had come to the meeting "in the name of the organization". He then pulled out a copy of Krivitsky's letter to Elsa. Krivitsky was deeply shocked, but denied having written the letter. He suspected that he knew he was lying. Brusse pleaded with Krivitsky to return to his work as a Soviet spy.

On 11th November, 1937, Walter Krivitsky had a meeting with Elsa Poretsky, Henricus Sneevliet, Pierre Naville and Gerard Rosenthal. Poretsky later recalled in Our Own People (1969) that Krivitsky said to her: "I come to warn you that you and your child are in grave danger. I came in the hope that I could be of some help." She replied: "Your warning comes too late. Had you done this in time Ignaz would be alive now, here with us... If you had joined him, as you said you would and as he expected, he would be alive and you would be in a different position." Krivitsky, visibly shocked by her response, said: "Of all that has happened to me this is the hardest blow."

Krivitsky then told the group that Brusse had showed him the letter that he had sent to Poretsky. He asked Rosenthal if he had showed the letter to anyone before giving it to Sneevliet. He admitted that he had asked Victor Serge to post the letter. He later admitted to Sneevliet that he had also shown it to Mark Zborowski. Krivitsky knew that one of these people had given a copy of the letter to Brusse, who had remained loyal to the NKVD.

Krivitsky believed the spy was either Serge or Zborowski. On 20th November, 1937, Krivitsky arranged to meet Serge on the Square Port-Royal. Serge later recalled in his book, Memoirs of a Revolutionary (1951) that Krivitsky was a "thin little man with premature wrinkles and nervous eyes". According to Serge, Krivitsky told him that he remained loyal to the Soviet Union, since "the historic mission of this state was far more important than its crimes, and besides he himself did not believe that any opposition could succeed".

Victor Serge commented that "Krivitsky was afraid of lighted streets. Each time that he put his hand into his overcoat pocket to reach for a cigarette, I followed his movements very attentively and put my own hand in my pocket." Krivitsky told Serge: "I am risking assassination at any moment and you still don't trust me, do you?" Serge admitted that was true. "And we would both agree to die for the same cause: isn't that so?" Serge replied: "Perhaps, all the same it would be as well to define just what this cause is."

When France was invaded by Germany in 1940, Serge managed to escape to Mexico where he continued to write. According to his biographer, Peter Sedgwick: "All these millions of words were typed by Serge in cramped single-spacing on reams of the cheapest flimsy, with rarely an erasure or amendment. When one manuscript was finished he went straight on to the next without looking back." His friend, Julián Gorkin, reading through his memoirs, commented that his material was so rich that it should be developed and expanded. Serge replied: "What would be the use? Who would publish me? And besides. I am pressed for time. Other books are waiting."

Victor Serge's health had been badly damaged by his periods of imprisonment in France and Russia. However, he continued to write until dying of a heart-attack in Mexico City on 17th November, 1947. He died penniless, and his friends had to make a collection among themselves to pay the expenses of his burial. It was several years later before his autobiography, Memoirs of a Revolutionary, and his last two novels, The Long Dusk and The Case of Comrade Tulayev, were published in the United States.