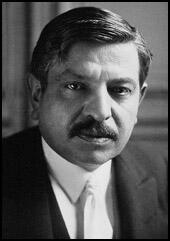

Pierre Laval

Pierre Laval, the son of Gilbert Laval and Claudine Tournaire, was born in Auvergnac, France, on 28th June, 1883. The family was comfortably off as they owned a café also served as a hostel and a butcher's shop, and Gilbert Laval owned a vineyard and horses.

After obtaining degrees in law and natural sciences he went into business. A member of the Socialist Party, Laval was elected to parliament in 1903. On the outbreak of the First World War Laval joined the French Army.

After the war Laval political views changed dramatically and he re-entered the Chamber of Deputies as a right-wing conservative. One opponent pointed out that this was no surprising as Laval reads the same from the left or the right.

Over the next few years he held several cabinet posts including foreign minister and was prime minister in 1931-32 and 1935-36. During his periods of office he worked closely with Aristide Briand to establish good relations with Germany and the Soviet Union.

In October 1935 Laval joined with Samuel Hoare, Britain's foreign secretary, in an effort to resolve the crisis created by the Italian invasion of Ethiopia. The secret agreement, known as the Hoare-Laval Pact, proposed that Italy would receive two-thirds of the territory it conquered as well as permission to enlarge existing colonies in East Africa. In return, Ethiopia was to receive a narrow strip of territory and access to the sea. Details of the Hoare-Laval Pact was leaked to the press on 10th December, 1935. The scheme was widely denounced as appeasement of Italian aggression and Laval and Hoare were both forced to resign.

Laval returned to pursue his business career and built up a commercial empire based on newspapers, printing, and radio. When the German Army occupied France in 1940 Laval used his media empire to support Henri-Philippe Petain and the Vichy government. He also used his influence in the National Assembly to give Petain dictatorial powers. Two days later on 12th July 1940, Laval was named as head of the government and Petain's legal successor.

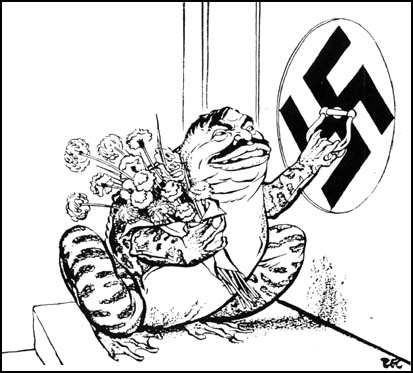

Laval developed a close relationship with Otto Abetz, the German ambassador in France, and on 22nd October, 1940, he met Adolf Hitler and proposed that the two countries should work closely together. At another meeting with Hermann Goering later that month Laval suggested a military alliance with Nazi Germany.

Some members of the government became concerned about these developments and on 13th December 1940, Henri-Philippe Petain ordered the sacking of Laval. He was also briefly arrested but Otto Abetz sent in troops to have him released and he was taken to Paris where he lived under the protection of the German Army. However on 27th August, 1941, a young student, Paul Collette, managed to fire four shots into Laval while seeing off French volunteer troops to take part in Operation Barbarossa.

Laval recovered and by the spring of 1942 he was ready to return to political life. After coming under increasing pressure from Otto Abetz, the German ambassador, Henri-Philippe Petain agreed on 18th April 1942 to recall Laval as head of the French government.

Laval now ordered the French police to begin rounding up Jews in France. He also took the controversial decision in June 1942 to send skilled labourers to Germany in exchange for French prisoners of war. In September he gave permission for the Gestapo to hunt down the French Resistance in unoccupied France.

In January, 1943, Laval created Milice, a political police force under the leadership of Joseph Darnard. Within six months their were over 35,000 men in the force and were playing the leading role in capturing Jews and left-wing activists and having them deported to Nazi Germany.

After the D-Day Landings Laval moved his government to Belfort. With the allied forces making good progress Laval retreated to Sigmaringen and in May 1945 he fled to Spain. He was interned in Barcelona and on 30th July was handed over to the new French government headed by General Charles De Gaulle.

Pierre Laval was charged with aiding the enemy and violating state security. He was found guilty and was shot by a firing squad at Fresnes Prison in Paris on 15th October, 1945.

Primary Sources

(1) Pierre Laval, in conversation with Robert Boothby (March 1940)

I want to tell you that I think this war is a great mistake. If we had come to terms with Mussolini, as I wanted to do, we might have held Germany. That is no longer possible. We have given most of Europe to Hitler. Let us try to hold on to what we have got left. I am a peasant from the Auvergne. I want to keep my farm, and I want to keep France. Nothing else matters now.

(2) Otto Abetz, the German ambassador protested to Henri-Philippe Petain when Pierre Laval was removed from the French government (17th December, 1940)

The Fuhrer considers the conduct of the French government towards Laval a personal affront. While Germany did not want to impair the French government's freedom of action in any way in case of a French refusal (to reinstate him) she would not continue the policy of co-operation which had been made possible at Montoire.

(3) George Orwell, BBC radio broadcast (18th April 1942)

There is very bad news in the fact that Laval has returned to the French Cabinet. Laval is a French millionaire who has been known for many years to be a direct agent of the Nazi Government. He played a leading part in the intrigues which led to the downfall of France and since the Armistice has steadily worked for what is called

'collaboration' between France and Germany, meaning that France should throw in its lot with the Axis, send an army to take part in the war against Russia, and use the French Fleet against Britain. For over a year he has been kept out of office, thanks to American pressure, and his return probably means that diplomatic relations between France and the USA will now come to an end. The American Government is already recalling it's ambassador and has advised its nationals to leave France. This is perhaps no bad thing in itself, for there is very little doubt that German submarines operating in the Atlantic have habitually made use of French ports, both in Africa and in the West Indies, and the fact that France and America were theoretically on friendly terms has made these manoeuvres harder to deal with. If relations are broken off, the Americans will at any rate not feel that their hands are tied by the so-called neutrality of France. Nevertheless, there is very great danger that at some critical moment Laval may succeed in throwing the French Fleet into battle against the British Navy, which is already struggling against the combined navies of three nations.

(4) Pierre Laval, letter to William Leahy (22nd April, 1942)

In the event of a victory over Germany by Soviet Russia and England, Bolshevism in Europe would inevitably follow. Under these circumstances I would prefer to see Germany win the war. I feel that an understanding could be reached (with Germany) which would result in a lasting peace with Europe and believe that a German victory is preferable to a British and Soviet victory.

(5) Pierre Laval, speech to a meeting of French politicians (September, 1942)

Clearly, for France in her present position, intelligence consists of practicing a policy of entente with Germany in order to survive. But the same intelligence compels Germany to practise the same policy. I defy anyone - and I have said this to the Germans - to build a solid, articulated, and viable Europe without France's consent. France cannot be destroyed. She is an old country who, despite her misfortunes, has, and always will have, thanks to her past, a tremendous prestige in the world, whatever the fate inflicted upon her.

(6) Pierre Laval, letter to Jacques Barnaud (September, 1942)

If the Germans are beaten, General de Gaulle will return. He will be supported by 80 or 90 per cent of the French people and I shall be hanged.

(7) Pierre Laval, radio broadcast explaining the exchange-scheme (22nd June, 1942)

Workers of France, it is for the freedom of the prisoners that you will go to work in Germany! It is for our country that you will go in large numbers! It is in order that France may find her place in the new Europe that you will respond to my appeal.

(8) William Leahy, ambassador to Vichy government, wrote about Pierre Laval in his memoirs, I Was There (1950)

The figure of Pierre Laval hung like an evil shadow over Vichy as the year opened. The former Prime Minister was a shrewd and able politician who staked his own future and that of France on an Axis victory. He was favoured by the German occupation authorities. A test of strength between Germany and the United States in Vichy was in the making as 1942 opened. It was to result in April in a temporary

victory for Laval when the Germans forced the Marshal to take him back into the Government, which event necessitated my recall to Washington.

He was a small man, swarthy-complexioned, careless in his personal appearance, but with a pleasing manner of speech. In a very frank discussion of his policies, Laval gave the impression of being fanatically devoted to his country, with a conviction that the interests of France were bound irrevocably with those of Germany. One's impression necessarily was qualified by persistent reports that he had used his political

offices to advance his private personal fortune. It was true that, starting with nothing, he had advanced from a poor delivery boy in a provincial town grocery to become a very rich man and a power in his country.

He convinced me that his Government was fully committed and might be expected to go as far as it could to collaborate with Germany and assist in the defeat of what he termed Soviet-British Bolshevism. Pierre Laval definitely was not on our side in this war.

(9) After the war, Andre Guenier, Laval's former private secretary, attempted to defend his former boss.

Laval never suspected the inhuman system and the atrocities to which the people who were arrested and deported to the east were subjected. If he had known, none of the considerations which compelled him to hang on to a government of the country, however serious, would have retained their validity. He would have denounced the fact before the civilized world and would have refused any contact with the representatives of a government indulging in such acts of barbarism.

(10) After the defeat of Nazi Germany Laval made a desperate attempt to escape to Spain. This is a telegram he sent to the Spanish government on 17th April, 1945.

It is neither the statesman nor the friend who is asking your help and assistance, but simply the man. I ask you in my own name as well as in that of my wife and my faithful friend, Maurice Gabolde, for permission to enter Spain and await for better days. Today it is a tired and worn-out old man who is writing to you and, in memory of our long friendship, I thank you in advance.