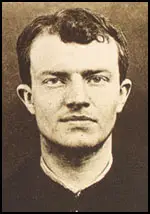

René Valet

René Valet was born in Verdun on 27th May 1890. He moved to Paris where he established himself as a locksmith. His friend, Victor Serge, later wrote: "Rene Valet, my friend, was a lively, restless spirit. We had met in the Quarter Latin, we had discussed everything together, usually at night... I remember his fine, square-set ginger head, his powerful chin, his green eyes, his strong hands, his athlete's bearing (an emancipated athlete, naturally). He liked to wear the navvy's wide corduroy trousers, with a waistband of blue flannel. Once, on an evening of riots, we wandered together around a guillotine, ridden by our gloom, sickened by our feebleness, mad with anger."

Both men were anarchists but Valet became an illegalist. According to one activist: "The anarchist is in a state of legitimate defence against society. Hardly is he born than the latter crushes him under a weight of laws, which are not of his doing, having been made before him, without him, against him. Capital imposes on him two attitudes: to be a slave or to be a rebel; and when, after reflection, he chooses rebellion, preferring to die proudly, facing the enemy, instead of dying slowly of tuberculosis, deprivation and poverty, do you dare to repudiate him? If the workers have, logically, the right to take back, even by force, the wealth that is stolen from them, and to defend, even by crime, the life that some want to tear away from them, then the isolated individual must have the same rights."

Valet told Serge: "We have a wall in front of us, and what a wall." According to Serge: "The next day he confessed to me that all that night his hand had been closed upon the chill blackness of a Browning revolver. Fight, fight, what else was there to do? And if it meant death, no matter. Rene rushed into mortal danger out of his sense of solidarity with his defeated mates, out of his need for battle, and, at the heart of it, out of despair. These 'conscious egoists' were going to get themselves slaughtered for friendship's sake.

In 1911 Valet joined a gang led by Jules Bonnot. Other members included Raymond Callemin, André Soudy, Stephen Monier, Octave Garnier and Edouard Carouy. Richard Parry, the author of the The Bonnot Gang (1987) has argued: "The so-called 'gang', however, had neither a name nor leaders, although it seems that Bonnot and Garnier played the principal motivating roles. They were not a close-knit criminal band in the classical style, but rather a union of egoists associated for a common purpose. Amongst comrades they were known as 'illegalists', which signified more than the simple fact that they carried out illegal acts. Illegal activity has always been part of the anarchist tradition, especially in France."

On 21st December, 1911 the gang robbed a messenger of the Société Générale Bank of 5,126 francs in broad daylight and then fled in a stolen Delaunay-Belleville car. It is claimed that they were the first to use an automobile to flee the scene of a crime. As Peter Sedgwick pointed out: "This was an astounding innovation when policemen were on foot or bicycle. Able to hide, thanks to the sympathies and traditional hospitality of other anarchists, they held off regiments of police, terrorized Paris, and grabbed headlines for half a year."

The gang then stole weapons from a gun shop in Paris. On 2nd January, 1912, they broke into the home of the wealthy Louis-Hippolyte Moreau and murdered both him and his maid. This time they stole property and money to the value of 30,000 francs. Bonnot and his men fled to Belgium, where they sold the stolen car. In an attempt to steal another they shot a Belgian policeman. On 27th February they shot two more police officers while stealing an expensive car from a garage in Place du Havre.

On 25th March, 1912, the gang stole a De Dion-Bouton car in the Sénart Forest by killing the driver. Later that day they killed two cashiers during an attack on the Société Générale Bank in Chantilly. Leading anarchists in the city were arrested. This included Victor Serge who complained in his autobiography, Memoirs of a Revolutionary (1951): "A positive wave of violence and despair began to grow. The outlaw anarchists shot at the police and blew out their own brains. Others, overpowered before they could fire the last bullet into their own heads, went off sneering to the guillotine.... I recognized, in the various newspaper reports, faces I had met or known; I saw the whole of the movement founded by Libertad dragged into the scum of society by a kind of madness; and nobody could do anything about it, least of all myself. The theoreticians, terrified, headed for cover. It was like a collective suicide."

The police offered a reward of 100,000 in an effort to capture members of the gang. This policy worked and on information provided by an anarchist writer, André Soudy was arrested at Berck-sur-Mer on 30th March. This was followed a few days later when Edouard Carouy was betrayed by the family hiding him. Raymond Callemin was captured on 7th April.

On 24th April, 1912, three policemen surprised Jules Bonnot in the apartment of a man known to buy stolen goods. He shot at the officers, killing Louis Jouin, the vice-chief of the French police, and wounding another officer before fleeing over the rooftops. Four days later he was discovered in a house in Choisy-le-Roi. It is claimed the building was surrounded by 500 armed police officers, soldiers and firemen. Bonnot was able to wound three officers before the house before the police used dynamite to demolish the front of the building. In the battle that followed Bonnot was shot ten times. He was moved to the Hotel-Dieu de Paris before dying the following morning.

Valet remained on the run with Octave Garnier until 15th May, 1912. According to Victor Serge: "Octave Garnier and René Valet, caught up at Nogent-sur-Marne in a villa where they were hiding out with their women, underwent an even longer siege, taking on the civil police, the gendarmerie, and the Zouaves. They fired hundreds of bullets, viewing their attackers as murderers (and themselves as victims) and, when the house was dynamited, blew out their own brains."

Primary Sources

(1) Victor Serge, Memoirs of a Revolutionary (1951)

Rene Valet, my friend, was a lively, restless spirit. We had met in the Quarter Latin, we had discussed everything together, usually at night, around the Ste. Genevieve hill, in the little bars jostling on the Boulevard St. Michel: Barres, Anatole France, Apollinaire, Louis Nazzi. Together we muttered scraps of Vildrac's White Bird, Jules Romains's Ode to the Crowd, Jehan Rictus's The Ghost. Rene was law-abiding and prosperous, he even had his own locksmith's workshop, not far from Denfert-Rochereau. I can see him there now, standing up like a young Siegfried, criticizing Anatole France's treatment of the destruction of this planet. Having had his say, Rene would sink slowly down on the asphalt of the boulevard, with a sly grin. "What is certain is that we are all mugs. Yes, mugs."

I remember his fine, square-set ginger head, his powerful chin, his green eyes, his strong hands, his athlete's bearing (an emancipated athlete, naturally). He liked to wear the navvy's wide corduroy trousers, with a waistband of blue flannel. Once, on an evening of riots, we wandered together around a guillotine, ridden by our gloom, sickened by our feebleness, mad with anger. "We have a wall in front of us," we told each other, "and what a wall." "Oh, the bastards!" muttered my ginger-headed friend, and next day he confessed to me that all that night his hand had been closed upon the chill blackness of a Browning revolver. Fight, fight, what else was there to do? And if it meant death, no matter. Rene rushed into mortal danger out of his sense of solidarity with his defeated mates, out of his need for battle, and, at the heart of it, out of despair. These "conscious egoists" were going to get themselves slaughtered for friendship's sake.