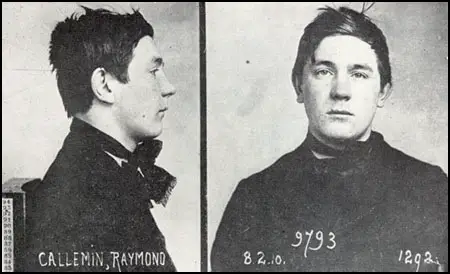

Raymond Callemin

Raymond Callemin, the son of a shoemaker, Narcissus Callemin, was born in Brussels on 26th March 1890. According to his childhood friend, Victor Serge: "Raymond Callemin grew up as much as he could in the street, anything to get away from the stifling back room that was his home, behind a cobbler's stall where his father patched the shoes of the locals from morning to night. His father was a decent but broken drunk, an old Socialist disgusted with Socialism."

In 1906 Callemin and Serge became friends with a group of anarchists that included Jean de Boe, Octave Garnier, René Valet and Edouard Carouy. The group became known as the Brussels Revolutionary Gang. Serge later wrote: "Anarchism swept us away completely because it both demanded everything of us and offered us everything. There was no corner of life that it failed to illumine; at least so it seemed to us...Shot through with contradictions, fragmented into varieties and sub-varieties, anarchism demanded, before anything else, harmony between deeds and words (which, in truth, is demanded by all forms of idealism, but which they all forget as they become complacent)."

Callemin and Serge moved to Paris. They became followers of Albert Libertad, the editor of l'Anarchie. Serge later recalled in his memoirs: "No one knew his real name, or anything of him before he started preaching. Crippled in both legs, walking on crutches which he plied vigorously in fights (he was a great one for fighting, despite his handicap), he bore, on a powerful body, a bearded head whose face was finely proportioned. Destitute, having come as a tramp from the south, he began his preaching in Montmartre, among libertarian circles and the queues of poor devils waiting for their dole of soup not far from the site of Sacre Coeur. Violent, magnetically attractive, he became the heart and soul of a movement of such exceptional dynamism that it is not entirely dead even at this day. Albert Libertad loved streets, crowds, fights, ideas, and women. On two occasions he set up house with a pair of sisters, the Mahes and then the Morands. He had children whom he refused to register with the State."

Jules Bonnot arrived in Paris in 1911. According to Victor Serge: "From the grapevine we gathered that Bonnot... had been traveling with him by car, had killed him, the Italian having first wounded himself fumbling with a revolver." Bonnot soon formed a gang that included local anarchists, Callemin, Octave Garnier, René Valet, André Soudy, Stephen Monier and Edouard Carouy. Serge was totally opposed to what the group intended to do. Callemin visited Serge when he heard what he had been saying: "If you don't want to disappear, be careful about condemning us. Do whatever you like! If you get in my way I'll eliminate you!" Serge replied: "You and your friends are absolutely cracked and absolutely finished."

On 21st December, 1911 the gang robbed a messenger of the Société Générale Bank in broad daylight and then fled in a car. As Peter Sedgwick pointed out: "This was an astounding innovation when policemen were on foot or bicycle. Able to hide, thanks to the sympathies and traditional hospitality of other anarchists, they held off regiments of police, terrorized Paris, and grabbed headlines for half a year."

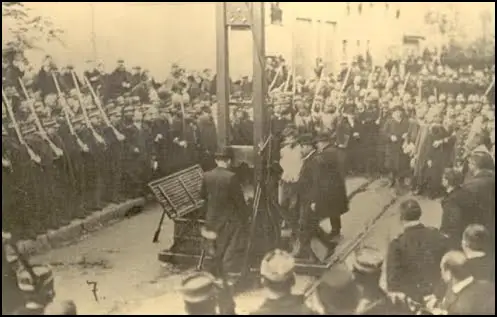

The gang murdered a police officer at the Place du Havre on 27th February, 1912. The following month, on 25th March, two more people were killed during an attack on the office of the General Corporation in Chantilly. Victor Serge complained in Memoirs of a Revolutionary (1951): "A positive wave of violence and despair began to grow. The outlaw anarchists shot at the police and blew out their own brains. Others, overpowered before they could fire the last bullet into their own heads, went off sneering to the guillotine.... I recognized, in the various newspaper reports, faces I had met or known; I saw the whole of the movement founded by Libertad dragged into the scum of society by a kind of madness; and nobody could do anything about it, least of all myself. The theoreticians, terrified, headed for cover. It was like a collective suicide."

Callemin was arrested on 7th April. Seventeen days later, three policemen surprised Jules Bonnot in the apartment of a man known to buy stolen goods. He shot at the officers, killing Louis Jouin, the vice-chief of the French police, and wounding another officer before fleeing over the rooftops. Four days later he was discovered in a house in Choisy-le-Roi. It is claimed the building was surrounded by 500 armed police officers, soldiers and firemen. Bonnot was able to wound three officers before the house before the police used dynamite to demolish the front of the building. In the battle that followed Bonnott was shot ten times. He was moved to the Hotel-Dieu de Paris before dying the following morning. Octave Garnier and René Valet were killed during a police siege of their suburban hideout on 15th May, 1912.

The trial of Raymond Callemin, Victor Serge, Rirette Maitrejean, Edouard Carouy, Jean de Boe, André Soudy, Eugène Dieudonné and Stephen Monier, began on 3rd February, 1913. According to Serge: "In the course of a month, 300 contradictory witnesses paraded before the bar of the court. The inconsequently of human testimony is astonishing. Only one in ten can record more or less clearly what they have seen with any accuracy, observe, and remember - and then be able to recount it, resist the suggestions of the press and the temptations of his own imagination. People see what they want to see, what the press or the questioning suggest."

Callemin, Soudy, Dieudonné and Monier were sentenced to death. When he heard the judge's verdict, Callemin jumped up and shouted: "Dieudonné is innocent - it's me, me that did the shooting!" Carouy was sentenced to hard labour for life (he committed suicide a few days later). Serge received five years' solitary confinement but Maitrejean was acquitted. Dieudonné was reprieved by Raymond Poincare but Callemin, Soudy and Monier were guillotined at the gates of the prison on 21st April, 1913.

Primary Sources

(1) Victor Serge, Memoirs of a Revolutionary (1951)

The end of 1911 saw dramatic happenings. Joseph the Italian, a little militant with frizzled hair who dreamed of a free life in the bush of Argentina, as far away as possible from the towns, was found murdered on the Melun Road. From the grapevine we gathered that an individualist from Lyons, Bonnot by name (I did not know the man), who had been traveling with him by car, had killed him, the Italian having first wounded himself fumbling with a revolver. However it may have happened, one comrade had murdered or "done" another. An informal investigation shed no light on the matter and only annoyed the "scientific" illegalists. Since I had expressed hostile opinions towards them, I had an unexpected visit from Raymond. "If you don't want to disappear, be careful about condemning us." He added, laughingly, "Do whatever you like! If you get in my way I'll eliminate you!"

"You and your friends are absolutely cracked," I replied, "and absolutely finished." We faced each other exactly like small boys over a red cabbage. He was still squat and strapping, baby-faced and merry. "Perhaps that's true," he said, "but it's the law of nature."

A positive wave of violence and despair began to grow. The outlaw anarchists shot at the police and blew out their own brains. Others, overpowered before they could fire the last bullet into their own heads, went off sneering to the guillotine. "One against all!" "Nothing means anything to me!" "Damn the masters, damn the slaves, and damn me!" I recognized, in the various newspaper reports, faces I had met or known; I saw the whole of the movement founded by Libertad dragged into the scum of society by a kind of madness; and nobody could do anything about it, least of all myself. The theoreticians, terrified, headed for cover. It was like a collective suicide. The newspapers put out a special edition to announce a particularly daring outrage, committed by bandits in a car on the Rue Ordener in Montmartre, against a bank cashier carrying half a million francs. Reading the descriptions, I recognized Raymond and Octave Garnier, the lad with piercing black eyes who distrusted intellectuals. I guessed the logic of their struggle: in order to save Bonnot, now hunted and trapped, they had to find either money, money to get away from it all, or else a speedy death in this battle against the whole of society. Out of solidarity they rushed into this squalid, doomed struggle with their little revolvers and their petty, trigger-happy arguments. And now there were five of them, lost, and once again without money even to attempt flight, and against them towered Money - 100,000 francs' reward for the first informer.