Albert Libertad

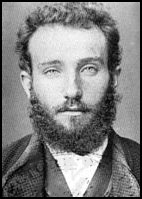

Albert Libertad was born in Bordeaux on 24th November 1875. He lost the use of his legs as a result of a childhood illness. Soon afterwards he was abandoned by his parents. Libertad moved to Montmartre in 1896 and he gradually emerged as a significant figure in the anarchist movement in the city.

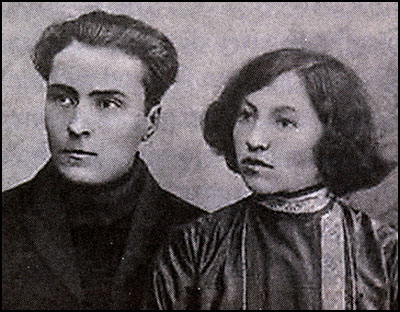

In 1905 Libertad established l'Anarchie. Contributors to the journal included Victor Serge, Rirette Maitrejean and Emile Armand. In the 1906 General Election he called on people not to vote: "As usual, they will insult each other, slander each other, fight each other. Blows will be exchanged for the benefit of third thieves, always ready to profit from the stupidity of the crowd. Why will you go for this? You live with your kids in unhealthy lodgings. You eat – when you can – food adulterated by the greed of traffickers. Exposed to the ravages of alcoholism and tuberculosis, you wear yourself out from morning to night at a job that is always imbecilic and useless and that you don’t even profit from. The next day you start over again, and so it goes till you die. Is it then a question of changing all this? Are they going to give you the means of realizing a flourishing existence, you and your comrades? Are you going to be able to come and go, eat, drink, breathe without constraint, love with joy, rest, enjoy scientific discoveries and their application, decreasing your efforts, increasing your well-being. Are you finally going to live without disgust or care the large life, the intense life? No, say the politicians proposed for your suffrage. This is only a distant ideal...You must be patient...You are many, but you should also become conscious of your might so as to abandon it into the hands of your ‘saviors’ once every four years. But what will they do in their turn? Laws! What is the law? The oppression of the greater number by a coterie claiming to represent the majority. In any event, error proclaimed by the majority doesn’t become true, and only the unthinking bow before a legal lie. The truth cannot be determined by vote. He who votes accepts to be beaten."

Libertad called on the people to overthrow the government: "The anarchists alone are logical in revolt. The anarchists don’t vote. They don’t want to be the majority that commands; they don’t accept being the minority that obeys. When they rebel they have no need to break any contract: they never accept tying their individuality to any government of any kind. They alone, then, are rebels held back by no ties, and each of their violent gestures is in relation to their ideas, is logically consistent with their reasoning. By demonstration, by observation, by experience or, lacking these, by force, by violence, these are the means by which the anarchists want to impose themselves. By majority, by the law, never!"

In another article in l'Anarchie Libertad argued: "In present society, made foul by the conventional defecations of property, of patriotism, of religion, of family, of ignorance, crushed by the power of government and the inertia of the governed; I wish not to disappear, but to throw upon the scene the light of truth, to provide a disinfectant, to it by any means at my command. Even with death approaching, I shall have still the desire to chair my body by means of phenol or acid, for the sake of humanity’s health. And if I am destroyed in this effort, I shall not be totally effaced. I shall have reacted against the environment, I shall have lived briefly but intensely; I shall perhaps have opened a breach for the passage of energies similar to my own. No, it is not life that is bad, but the conditions in which we live. Therefore we shall address ourselves not to life, but to these conditions: let us change them. One must live, one must desire to live still more abundantly. Let us accept not even the partial suicides. Let us be eager to know all experiences, all happiness, all sensations.... Let us be champion of life; so that desires may arise out of our turpitude and weakness; let us assimilate the earth to our own concept of beauty. Thus may our wishes be united, magnificently; and at the last we shall know the Joy of Life in the absolute."

Victor Serge, who worked closely with Libertad described him in his autobiography, Memoirs of a Revolutionary (1951): "No one knew his real name, or anything of him before he started preaching. Crippled in both legs, walking on crutches which he plied vigorously in fights (he was a great one for fighting, despite his handicap), he bore, on a powerful body, a bearded head whose face was finely proportioned. Destitute, having come as a tramp from the south, he began his preaching in Montmartre, among libertarian circles and the queues of poor devils waiting for their dole of soup not far from the site of Sacre Coeur. Violent, magnetically attractive, he became the heart and soul of a movement of such exceptional dynamism that it is not entirely dead even at this day. Albert Libertad loved streets, crowds, fights, ideas, and women. On two occasions he set up house with a pair of sisters, the Mahes and then the Morands. He had children whom he refused to register with the State."

Albert Libertad died in a street fight on 12th November, 1908.

Primary Sources

(1) Albert Libertad, l'Anarchie (4th May, 1905)

The national and international holiday of the organized proletariat.

The Bastille Day of the unionized working class, the replay of the holiday of the Bistros.

The tragi-comic anniversary of something that will be taken away ...

May Day 1905: Prologue

In the archiepiscopal church the grand ceremony takes place: the high priests, who have been delegated to other places, are absent.

The tribune is filled. The office is invaded. The strangest looking faces appear there. An assessor, delegate and secretary of I-don’t-know-what, who has decorated his breast with a large tie, with his decoration and his lit up mug, set the appropriate tone.

Appearing in a curious parade, all alone come the eternal bit players and the future stars. In the wings we can imagine the presence of influential directors falsifying the system.

Alcohol overflows in smelly burps from almost every mouth.

A few ordinary workers, a hundred at most, have come in a spirit of combativeness, or though obligation. There are a few who are sincere, thinking they are working for their emancipation, and who are sickened and disillusioned by the drunken events around them.

A bizarre salad where the words “Organized proletariat,” “workers demands,” “Eight hour day,” dance about. “All arise in 1906,” “The Bosses,” “The Exploiters,” “The Exploited,” “My Corporation,” “Delegates,” “The Union of...,"etc. are seasoned before us.

One has the impression of listening to a constantly wound up phonograph , but whose worn out notches allow only a few words to escape.

Any attempt at serious debate is impossible. We are in the hall not to learn but – it appears – to impress the bosses.

(2) Albert Libertad, l'Anarchie (17th May, 1906)

The bourgeois were frightened!!!

The bourgeois felt pass over them the wind of riot, the breath of revolt, and they feared the hurricane, the storm that would unleash those with unsatisfied appetites on their too well garnished tables.

The bourgeois were frightened!!!

The bourgeois, fat and tranquil, blissful and peaceful, heard the horrifying grumble of the painful and poor digestion of the thin, the rachitic, the unsatisfied. The bellies heard the rumblings of the arms, who refused to bring them their daily pittance.

The bourgeois were frightened!!!

The bourgeois gathered together their piles of money, their titles; they hid them in holes from the claws of the destroyers; the bourgeois stored their movable property, and they then looked around to see where to hide themselves. The big city wasn’t very safe with all those threats in the air. And the countryside wasn’t either... when the evening came chateaus were being burned down there.

The bourgeois were frightened! A fear that gripped their bellies, their stomachs, their throats, without any means of attenuating it presenting itself.

And so the bourgeois put up barricades of steel and blood in front of the of the workers, cemented with blood and flesh. . They tried to rejoice at seeing the little infantrymen and the heavy dragoons parade before their windows. They swooned before the handsome Republican Guards and the fine cavalrymen. And still, fear invaded their being. They were frightened.

That fear seemed to have something of remorse in it. One could believe that the bourgeois felt the logic of the acts that included everyone and everything that they alone had possessed up till then.

The bourgeois were afraid that suddenly, in a great movement, the two sides of the scale that had always inclined in the direction of their desires would suddenly be leveled. They believed the moment for disgorgement had finally come. Since their lives were made of the deaths of other men, they believed that on this day the lives of others would be made of their deaths.

O anguished dream! The bourgeois were frightened, really frightened!!

But the hurricane passed over their heads and the bellies and didn’t kill. The lightning rods of sabers and rifles sufficed for the few gusts that blew forgotten over society.

The worker again took up his labor. He again bent his back over the daily task. Today like yesterday, the slave prepares his master’s swill.

(3) Albert Libertad, l'Anarchie (2nd August, 1906)

We in Paris, almost without our knowledge, were threatened with a great revolution.

We were threatened with great perturbations in the slaughterhouses of La Villette.

A few snatches of reasons for this was allowed to reach indiscrete ears. Hoof and mouth was spoken of. But what is this alongside other reasons, ones we must know nothing of.

Only dead meat should leave the slaughterhouses of the city, and only living meat should enter.

But go see. Beasts enter, pulled on, pushed against. They must enter alive, with a breath, only a breath, hardly anything.

And the contaminated carrion is sold, served to the faubourgs of Paris from Menilmontant to Montrouge, from Belleville to La Chapelle.

Go, workers of the slaughterhouses, defend your “rights.” Go, butcher boys, defend “your own.” You must go on slaughtering, go on serving poisoned meat.

Go beef drivers, turn and re-turn your fever-bearing meats from the Beauce to Paris, from Paris to all the workers from the north, the west, and the east? Go ahead, come to Paris, contaminate your animals or bring here the poison contracted elsewhere.

What do evil gestures, useless gestures, poisonous gestures matter? One must live. And to work is to poison, to pillage, to steal, to lie to other men. Work means adulterating drinks, manufacturing cannons, slaughtering and serving slices of poisoned meat.

That’s what work means for the spineless meat that surrounds us, the meat that should be slaughtered and pushed into the sewers.

(4) Victor Serge, Memoirs of a Revolutionary (1951)

Anarchism swept us away completely because it both demanded everything of us and offered us everything. There was no remotest corner of life that it failed to illumine; at least so it seemed to us. A man could be a Catholic, a Protestant, a Liberal, a Radical, a Socialist, even a syndicalist, without in anyway changing his own life, and therefore life in general. It was enough for him, after all, to read the appropriate newspaper; or, if he was strict, to frequent the cafe associated with whatever tendency claimed his allegiance. Shot through with contradictions, fragmented into varieties and sub-varieties, anarchism demanded, before anything else, harmony between deeds and words (which, in truth, is demanded by all forms of idealism, but which they all forget as they become complacent). That is why we adopted what was (at that moment) the extremest variety, which by vigorous dialectic had succeeded, through the logic of its revolutialism, in discarding the necessity for revolution. To a certain extent we were impelled in that direction by our disgust with a certain type of rather mellow, academic anarchism, whose Pope was Jean Grave in Zerrzps Nouveaux. Individualism had just been affirmed by our hero Albert Libertad. No one knew his real name, or anything of him before he started preaching. Crippled in both legs, walking on crutches which he plied vigorously in fights (he was a great one for fighting, despite his handicap), he bore, on a powerful body, a bearded head whose face was finely proportioned. Destitute, having come as a tramp from the south, he began his preaching in Montmartre, among libertarian circles and the queues of poor devils waiting for their dole of soup not far from the site of Sacre Coeur. Violent, magnetically attractive, he became the heart and soul of a movement of such exceptional dynamism that it is not entirely dead even at this day. Albert Libertad loved streets, crowds, fights, ideas, and women. On two occasions he set up house with a pair of sisters, the Mahes and then the Morands. He had children whom he refused to register with the State. "The State? Don't know it. The name? I don't give a damn; they'll pick one that suits them. "Me law? To hell with it." He died in hospital in 1908 as the result of a fight, bequeathing his body ("That carcass of mine," he called it) for dissection in the cause of science.

His teaching, which we adopted almost wholesale, was: "Don't wait for the revolution. Those who promise revolution are frauds just like the others. Make your own revolution, by being free men and living in comradeship." Obviously I am simplifying, but the idea itself had a beautiful simplicity. Its absolute commandment and rule of life was: "Let the old world go to blazes." From this position there were naturally many deviations. Some inferred that one should "live according to Reason and Science," and their impoverished worship of science, which invoked the mechanistic biology of Felix le Dantec, led them on to all sorts of tomfoolery, such as a salt less, vegetarian diet and fruitarianism and also, in certain cases, to tragic ends. We saw young vegetarians involved in pointless struggles against the whole of society. Others decided, "Let's be outsiders. "The only place for us is the fringe of society." They did not stop to think that society has no fringe, that no one is ever outside it, even in the depth of dungeons, and that their "conscious egoism," sharing the life of the defeated, linked up from below with the most brutal bourgeois individualism.