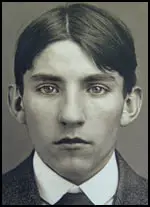

André Soudy

André Soudy was born in Beaugency on 25th February, 1892. He came from a very poor family and left school at eleven and later worked in a butcher's shop. Two years later he was diagnosed as suffering from tuberculosis. He became a petty criminal and eventually spent a year in prison after stealing a bicycle.

Soudy moved to Paris where he associated with a group of anarchists. This included Victor Serge who later wrote about him in his autobiography, Memoirs of a Revolutionary (1951): "I had often met Soudy at public meetings in the Latin Quarter. He was a perfect example of the crushed childhood of the back alleys. He grew up on the pavements: TB (tuberculosis) at thirteen, VD (syphilis) at eighteen, convicted at twenty (for stealing a bicycle). I had brought him books and oranges in the Tenon Hospital. Pale, sharp-featured, his accent common, his eyes a gentle gray... He earned his living in grocers' shops in the Rue Mouffetard, where the assistants rose at six, arranged the display at seven, and went upstairs to sleep in a garret after 9:00 p.m., dog-tired, having seen their bosses defrauding housewives all day by weighing the beans short, watering the milk, wine, and paraffin, and falsifying the labels... He was sentimental: the laments of street singers moved him to the verge of tears, he could not approach a woman without making a fool of himself, and half a day in the open air of the meadows gave him a lasting dose of intoxication. He experienced a new lease on life if he heard someone call him 'comrade' or explain that one could, one must, 'become a new man.' Back in his shop, he began to give double measures of beans to the housewives, who thought him a little mad. The bitterest joking helped him to live, convinced as he was that he was not long for this world". Soudy told Serge "I'm an unlucky blighter, nothing I can do about it."

In 1911 Soudy joined a gang led by Jules Bonnot. Other members included Raymond Callemin, René Valet, Stephen Monier, Octave Garnier and Edouard Carouy. Richard Parry, the author of the The Bonnot Gang (1987) has argued: "The so-called 'gang', however, had neither a name nor leaders, although it seems that Bonnot and Garnier played the principal motivating roles. They were not a close-knit criminal band in the classical style, but rather a union of egoists associated for a common purpose. Amongst comrades they were known as 'illegalists', which signified more than the simple fact that they carried out illegal acts. Illegal activity has always been part of the anarchist tradition, especially in France."

On 21st December, 1911 the gang robbed a messenger of the Société Générale Bank of 5,126 francs in broad daylight and then fled in a stolen Delaunay-Belleville car. It is claimed that they were the first to use an automobile to flee the scene of a crime. As Peter Sedgwick pointed out: "This was an astounding innovation when policemen were on foot or bicycle. Able to hide, thanks to the sympathies and traditional hospitality of other anarchists, they held off regiments of police, terrorized Paris, and grabbed headlines for half a year."

The gang then stole weapons from a gun shop in Paris. On 2nd January, 1912, they broke into the home of the wealthy Louis-Hippolyte Moreau and murdered both him and his maid. This time they stole property and money to the value of 30,000 francs. Bonnot and his men fled to Belgium, where they sold the stolen car. In an attempt to steal another they shot a Belgian policeman. On 27th February they shot two more police officers while stealing an expensive car from a garage in Place du Havre.

On 25th March, 1912, the gang stole a De Dion-Bouton car in the Sénart Forest by killing the driver. Later that day they killed two cashiers during an attack on the Société Générale Bank in Chantilly. Leading anarchists in the city were arrested. This included Victor Serge who complained in his autobiography, Memoirs of a Revolutionary (1951): "A positive wave of violence and despair began to grow. The outlaw anarchists shot at the police and blew out their own brains. Others, overpowered before they could fire the last bullet into their own heads, went off sneering to the guillotine.... I recognized, in the various newspaper reports, faces I had met or known; I saw the whole of the movement founded by Libertad dragged into the scum of society by a kind of madness; and nobody could do anything about it, least of all myself. The theoreticians, terrified, headed for cover. It was like a collective suicide."

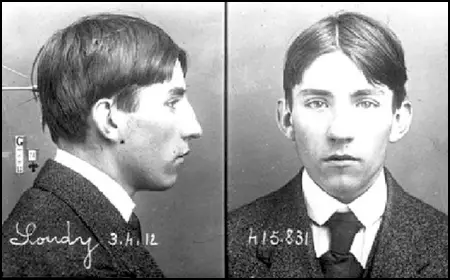

The police offered a reward of 100,000 in an effort to capture members of the gang. This policy worked and on information provided by an anarchist writer, André Soudy was arrested at Berck-sur-Mer on 30th March. This was followed a few days later when Edouard Carouy was betrayed by the family hiding him. Raymond Callemin was captured on 7th April.

On 24th April, 1912, three policemen surprised Bonnot in the apartment of a man known to buy stolen goods. He shot at the officers, killing Louis Jouin, the vice-chief of the French police, and wounding another officer before fleeing over the rooftops. Four days later he was discovered in a house in Choisy-le-Roi. It is claimed the building was surrounded by 500 armed police officers, soldiers and firemen.

According to Victor Serge: "They caught up with him at Choisy-le-Roi, where he defended himself with a pistol and wrote, in between the shooting, a letter which absolved his comrades of complicity. He lay between two mattresses to protect himself against the final onslaught." Bonnot was able to wound three officers before the house before the police used dynamite to demolish the front of the building. In the battle that followed Bonnot was shot ten times. He was moved to the Hotel-Dieu de Paris before dying the following morning. Octave Garnier and René Valet were killed during a police siege of their suburban hideout on 15th May, 1912.

The trial of Soudy, Raymond Callemin, Victor Serge, Rirette Maitrejean, Edouard Carouy, Jean de Boe, Eugène Dieudonné and Stephen Monier, began on 3rd February, 1913. According to Serge: "In the course of a month, 300 contradictory witnesses paraded before the bar of the court. The inconsequently of human testimony is astonishing. Only one in ten can record more or less clearly what they have seen with any accuracy, observe, and remember - and then be able to recount it, resist the suggestions of the press and the temptations of his own imagination. People see what they want to see, what the press or the questioning suggest."

Callemin, Soudy, Dieudonné and Monier were sentenced to death. When he heard the judge's verdict, Callemin jumped up and shouted: "Dieudonné is innocent - it's me, me that did the shooting!" Carouy was sentenced to hard labour for life (he committed suicide a few days later). Serge received five years' solitary confinement but Maitrejean was acquitted.

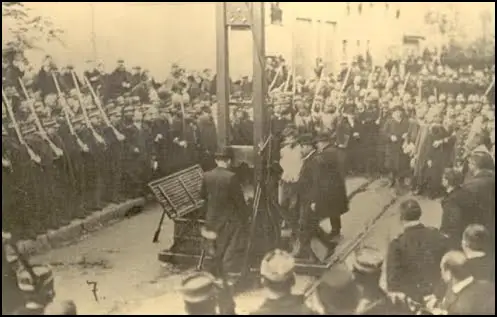

The date selected for Soudy's execution was 21st April, 1913. Victor Serge commented: "Soudy's last-minute request was for a cup of coffee with cream and some croissants, his last pleasure on earth, appropriate enough for that gray morning when people were happily eating their breakfasts in the little bistros. It must have been too early, for they could only find him a little black coffee." Soudy commented: "Out of luck right to the end."

According to Serge "he was fainting with fright and nerves, and had to be supported while he was going down the stairs; but he controlled himself and, when he saw the clearness of the sky over the chestnut trees, hummed a sentimental street song." Another witness heard Soudy say: "I haven't got the taking of any human life on my conscience. Things have come to a sorry end, but I'll have courage to the last. My poor mother!" He added: "It's the best thing, it's better than the forced labour camp".

Primary Sources

(1) Victor Serge, Memoirs of a Revolutionary (1951)

They were wandering in the city without escape, ready to be killed somewhere, anywhere, in a tram or a cafe, content to feel utterly cornered, expendable, alone in defiance of a horrible world. Out of solidarity, simply to share this bitter joy of trying to be killed, without any illusions about the struggle (as a good many told me when I met them in prison afterwards), others joined the first few such as red-haired René Valet (he too was a restless spirit) and poor little André Soudy. I had often met Soudy at public meetings in the Latin Quarter. He was a perfect example of the crushed childhood of the back alleys. He grew up on the pavements: TB (tuberculosis) at thirteen, VD at eighteen, convicted at twenty (for stealing a bicycle). I had brought him books and oranges in the Tenon Hospital. Pale, sharp-featured, his accent common, his eyes a gentle gray, he would say, "I'm an unlucky blighter, nothing I can do about it." He earned his living in grocers' shops in the Rue Mouffetard, where the assistants rose at six, arranged the display at seven, and went upstairs to sleep in a garret after 9:00 p.m., dog-tired, having seen their bosses defrauding housewives all day by weighing the beans short, watering the milk, wine, and paraffin, and falsifying the labels... He was sentimental: the laments of street singers moved him to the verge of tears, he could not approach a woman without making a fool of himself, and half a day in the open air of the meadows gave him a lasting dose of intoxication. He experienced a new lease on life if he heard someone call him "comrade" or explain that one could, one must, "become a new man." Back in his shop, he began to give double measures of beans to the housewives, who thought him a little mad. The bitterest joking helped him to live, convinced as he was that he was not long for this world, "seeing the price of medicine."

(2) Victor Serge, Memoirs of a Revolutionary (1951)

Soudy's last-minute request was for a cup of coffee with cream and some croissants, his last pleasure on earth, appropriate enough for that gray morning when people were happily eating their breakfasts in the little bistros. It must have been too early, for they could only find him a little black coffee. "Out of luck," he remarked, "right to the end." He was fainting with fright and nerves, and had to be supported while he was going down the stairs; but he controlled himself and, when he saw the clearness of the sky over the chestnut trees, hummed a sentimental street song: "Hail, 0 last morning of mine:" Monier, usually taciturn, was crazy with anxiety but mastered himself and became calm. I learned these details only a long time afterwards.

(3) Richard Parry, The Bonnot Gang (1987)

As dawn broke, there was a sudden flurry of activity inside the prison. At four-ten am the doors to cells seven, eleven and twelve were unlocked and a warder growled, "Get up, let's go", followed by a deputy of the public prosecutor's office who monotoned to Soudy and Monier, "Your plea is rejected".

André Soudy asked for a cup of coffee and two croissants, and enquired whether his comrades had been pardoned. Following a reply in the negative, he soliloquized, "I haven't got the taking of any human life on my conscience. Things have come to a sorry end, but I'll have courage to the last. My poor mother!". He was shivering as he dressed himself, but explained, "like Mayor Bailly,' it's due to the cold". Lastly, before leaving the cell he added, "It's the best thing, it's better than the forced labour camp".

Raymond was asked by the Deputy Public Prosecutor if he had any revelations to make, but declared that he had nothing further to say. He scribbled a few lines on a piece of paper that he handed to his lawyer, Boucheron. Exiting the cell, he said aloud, "It's a day without a tomorrow", and then, "It's a fine thing, eh? The final agony of a man".

Monier declared that he too would have courage to the end, then shook hands with some of the detectives from the Surete who were there. As he walked along the corridor, he mused, "I suspected yesterday that it would be this morning...I had a wonderful dream that I was making love". He addressed his lawyer; "Embrace Marie Besse for me".As the prisoners washed, Raymond asked for a glass of water, while Monier turned down the offer of a glass of rum, saying jocularly, "I don't want to get drunk". The three men were chained hand and foot then led out to the tumbril traditionally used to convey the condemned to the guillotine. They arrived in the boulevard Arago at four thirty-five am. André Soudy, still shivering, was the first to mount the scaffold. He turned and said, "it's so cold... goodbye"; Elie Monier replied, "So long".

Soudy was told to lie flat, and then secured in place. The blade fell, and his severed head tumbled into the basket. It was Raymond's turn next. He gave one of his habitual sardonic smiles and, addressing the few men gathered around the guillotine, repeated "It's fine, eh? A man's final agony". Then he too was decapitated. Lastly came Elie Monier, who said in a loud voice, "Goodbye to you all Messieurs and to Society as well". The blade fell for the third time.

Callemin's body was taken to the Faculty of Medicine as he had wished, to be used in the furtherance of scientific research; Monier was buried in the cemetery of Ivry-Parisien, and Soudy's body was claimed by his mother for burial in Beaugency, his birthplace.