On this day on 8th November

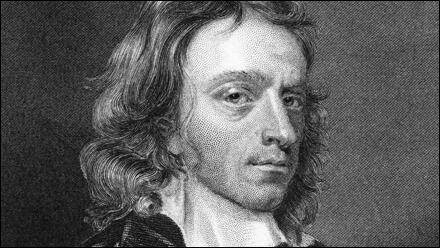

On this day in 1674 John Milton died. While at university began writing poetry in Latin, Italian and English. Over the next few years his fame grew with works such as Ode Upon the Morning of Christ's Nativity (1629), On Shakespeare (1632), Lycidas (1637) and Epitaphium Damonis (1639).

Milton was touring Italy when he heard about the conflict between Charles I and Parliament. Milton, a Puritan, returned to England to support the rebels. This included the publication of several pamphlets attacking the Anglican Church such as Of Reformation (1641), Of Prelatical Episcopacy (1641), The Reason of Church Government (1642) and Apology for Smectymnuus (1642).

In 1642 Milton married Mary Powell. However, after six weeks, upset by his political views, she returned to her Royalist family. This resulted in him publishing The Doctrine and Discipline of Divorce (1643), where he argued that an incompatibility of mind and spirit was a better ground for divorce than adultery. This was followed by On Education (1644) and Areopagitica, A Speech for the Liberty of Unlicensed Printing (1644), a passionate argument for a free press.

Milton's wife returned in 1645 and the couple had four children: Anne (1646), Mary (1648), John (1651) and Deborah (1652). Soon after the birth of Deborah, Milton's wife and son John died.

Milton, a staunch republican, supported the trial and execution of Charles I and in 1649 published The Tenure of Kings and Magistrates. During the Commonwealth Milton was Latin Secretary to the Council of State. His assistant was his close friend, Andrew Marvell. Marvell's help became even more important after Milton lost his sight in 1651. He continued to write and published several pamphlets including Pro Populo Anglicano Defensio (1651), Defensio Secunda (1654) and Defensio Pro Populo Anglicano (1655).

Milton also wrote poems praising Oliver Cromwell, Thomas Fairfax and Henry Vane. However, Milton grew increasingly concerned about the authoritarianism of Cromwell's government. On Cromwell's death Milton published The Ready and Easy Way to Establish a Free Commonwealth.

After the Restoration Milton's work was burnt in public. Milton went briefly into hiding fearing he would be executed as a Regicide. Over the next few years he devoted himself to writing and during this period published Paradise Lost (1667), The History of Britain (1670), Paradise Regained (1671), Samson Agonistes (1671) and Of True Religion (1673).

On this day in 1830 the Duke of Wellington made it clear in Parliament that he had no intention of introducing parliamentary reform. Charles Greville wrote in his journal: "The Duke of Wellington made a violent and uncalled for declaration against Reform, which has without doubt sealed his fate. Never was there an act of more egregious folly, or one so universally condemned by friends and foes." When news of what Wellington had said in Parliament was reported, his home in London was attacked by a mob. Now extremely unpopular with the public, Wellington began to consider resigning from office.

Wellington's biographer, Norman Gash has argued: "The duke made his celebrated declaration, in the debate on the king's speech at the beginning of November, that the constitution needed no improvement and that he would resist any measure of parliamentary reform as long as he was in office. Couched in his usual peremptory and uncompromising style, his statement was probably intended not so much to win back the ultra-tories (the usual interpretation placed on it at the time) as to make his own attitude plain and so put a stop to all the talk of parliamentary reform which had been going on, both outside and inside the administration, for several weeks."

On 15th November, 1830 Wellington's government was defeated in a vote in the House of Commons. The new king, William IV, was more sympathetic to reform than his predecessor and two days later decided to ask Earl Grey to form a government. As soon as Grey became prime minister he formed a cabinet committee to produce a plan for parliamentary reform. Details of the proposals were announced on 3rd February 1831. The bill was passed by the Commons by a majority of 136, but despite a powerful speech by Earl Grey, the bill was defeated in the House of Lords by forty-one.

On this day in 1897 Dorothy Day was born. Her father John Day, was a journalist. In her autobiography, The Long Loneliness (1952) she recaled: "Being from Tennessee, he had the prevalent attitude of the South toward the Negro. He distrusted all foreigners and agitators... Probably his greatest unhappiness came from us whose ideas he did not understand and which he thought were subversive and dangerous to the peace of the country."

Dorothy's brother, Donald Day, began working for The Day Book, and at a penny a copy, it aimed for a working-class market, crusading for higher wages, more unions, safer factories, lower streetcar fares, and women’s right to vote. It also tackled the important stories ignored by most other dailies. According to Duane C. S. Stoltzfus, the author of Freedom from Advertising (2007): "The Day Book served as an important ally of workers, a keen watchdog on advertisers, and it redefined news by providing an example of a paper that treated its readers first as citizens with rights rather than simply as consumers."

Day later admitted that the newspaper informed her about people like Eugene Debs and organisations such as the Industrial Workers of the World: "Through the paper I learned of Eugene Debs, a great and noble labor leader of inspired utterance. There were also accounts of the leaders of the Industrial Workers of the World who had been organizing in their one great union so that there were a quarter of a million members throughout the wheatfields, mines, and woods of the Northwest, as well as in the textile factories in the East."

A favourite author of Day's was Peter Kropotkin. "Kropotkin especially brought to my mind the plight of the poor, of the workers, and though my only experience of the destitute was in books." Kropotkin introduced Day to anarchism. She also became very interested in the ideas of Francisco Ferrer, an anarchist who had been executed in Barcelona in 1909 and Emma Goldman, who at the time was was a great advocate of free love. Although she approved of Goldman's anarchism she was "revolted by such promiscuity".

Day was keen to become a journalist like her father and brothers. In June 1916 she found work with the socialist journal, the New York Call. Chester Wright initially paid her $5 a week but eventually raised it to $12. One of her assignments was to interview Leon Trotsky who was living in exile on the Lower East Side. Trotsky told her that "where parliamentarianism was weakest the socialist movement was the strongest". He thought the First World War would lead to revolution: "The social unrest after the war will eclipse anything the world has ever seen."

A fellow journalist at the newspaper was Michael Gold. He used to visit her in her room and the landlady notified her mother of "Dorothy's immoral conduct". Jim Forest argues in his biography of Day, Love is the Measure (1986): "It is not surprising that gossip about them continued to be plentiful. The two spent long hours walking the streets, sitting on piers along the waterfront on the East River, talking about life and sharing experiences about the passion that had brought them both to The Call - the sufferings of the poor."

On 2nd April 1917 Day resigned from New York Call. A few weeks later she joined The Masses, a radical journal edited by Max Eastman. The assistant editor, Floyd Dell, later recalled: "For a while my assistant on The Masses was Dorothy Day, an awkward and charming young enthusiast, with beautiful slanting eyes, who had been a reporter." Day became friendly with the talented John Reed: "He was a big, hearty Harvard graduate, a typical newspaperman, and very much the Richard Harding Davis reporter hero. Wherever there was excitement, wherever life was lived in high tension, there he was, writing, speaking, recording the moment, and heightening its intensity for everyone else."

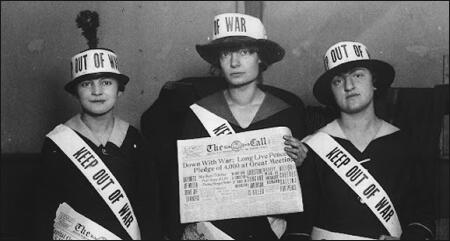

Day was also a supporter of women's suffrage and worked closely with Alice Paul and Lucy Burns of the Congressional Union for Women Suffrage (CUWS). The CUWS and attempted to introduce the militant methods used by the Women's Social and Political Union in Britain. This included organizing huge demonstrations and the daily picketing of the White House. In November 1917, Day was one of the 168 women arrested and jailed for "obstructing traffic". The women went on hunger strike and afraid that martyrs would be created, Woodrow Wilson ordered their release.

Like most of the people working for The Masses, Day believed that the First World War had been caused by the imperialist competitive system and that the USA should remain neutral. When the USA declared war on the Central Powers in 1917, The Masses came under government pressure to change its policy. When it refused to do this, the journal lost its mailing privileges.

In July, 1917, it was claimed by the authorities that cartoons by Art Young, Boardman Robinson and H. J. Glintenkamp and articles by Eastman and Floyd Dell had violated the Espionage Act. Under this act it was an offence to publish material that undermined the war effort. The legal action that followed forced The Masses to cease publication.

Day now decided to leave journalism and she signed up for a nurse's training program in Brooklyn. She also began attending services at St. Joseph's Catholic Church. Day later explained that she saw the Catholic Church as the "church of the poor". Religion also helped her deal with the psychological problems caused by an abortion that she had during a love affair with a journalist. This experience provided the material for her autobiographical novel, The Eleventh Virgin (1924).

In December 1932 Day met Peter Maurin, a Christian Brother. They decided to establish the Catholic Worker, a newspaper to publicize Catholic social teaching. The first edition appeared on 1st May, 1933. The newspaper criticised the economic system and supported organisation such as trade unions that were attempting to create a more equal society. It also argued that the Catholic Church should be a pacifist organization. Day and Maurin believed the nonviolent way of life was at the heart of the Gospel.

The Catholic Worker became a vehicle for creating a national movement. By 1936 there were 33 Catholic Worker Houses spread out across the country. These were charitable, self-help communities for people suffering the effects of the Depression. Today there are 130 of these houses in 32 states and eight foreign countries.

The Catholic Worker encountered problems during the Spanish Civil War. Most Catholics in the United States supported the fascists and saw Franco as the defender of the Catholic faith. As pacifists, Day and Maurin refused to support either side. As a result the newspaper lost two-thirds of its readers.

Day also maintained her pacifism during the Second World War. This was an unpopular stance to take and over the next few months fifteen Catholic Worker Houses were forced to close as volunteer workers withdrew their support from the organization.

After the war Day joined with David Dillinger and Abraham Muste to establish the Direct Action magazine in 1945. Dellinger once again upset the political establishment when he criticised the use of atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

In the 1950s Day became involved in the campaign against nuclear weapons. This led to Day being arrested several times for civil disobedience and was imprisoned four times between 1955 and 1959. Day was also involved in the campaign for black civil rights and an end to the Vietnam War. In 1973, aged 75, Day was imprisoned again after taking part in a banned picket line in support of the United Farm Workers in California.

As well as writing over 1,000 articles for the Catholic Worker, Day wrote several books including, Houses of Hospitality (1939), an account of the Catholic Worker movement, an autobiography, The Long Loneliness (1952) and On Pilgrimage: the Sixties (1972).

On this day in 1904 Cedric Belfrage, the son of a wealthy physician, was born in London. He lived in a house with 20 rooms and six servants. He was sent to Cambridge University with a manservant and what he later called a "meager" allowance of two pounds a week.

In 1924 he began writing film reviews for the Kinematograph Weekly in 1924. Three years later he moved to Hollywood and was employed as a film critic of the New York Sun. He also worked as a press agent for Sam Goldwyn. Belfrage became a socialist after becoming friends with the novelist, Upton Sinclair.

Belfrage explained that while at university he had no interest in politics. This changed while he was living in America. During the Great Depression he witnessed great inequality. Like many intelligent people at the time he became convinced that capitalism had failed. He said in an interview that he "could not stomach the inequalities" that he saw and he therefore became a socialist and an anti-fascist activist. As he admitted that this decision "started me on the road to ruin".

In the early 1930s he became the film critic of The Daily Express. One of Belfrage's reviews upset "the entire film industry in protest withdrew advertising from his paper. He quit dramatic reviewing for a time until the trouble blew over. He left on his round-the-world trip in January, 1934, and returned in December.... He then took up business at the old stand again." In April, 1936 he went on a visit to the Soviet Union with his wife, the journalist Molly Castle.

Belfrage became an active member of the Hollywood Anti-Nazi League (HANL) in 1936. Other members included Dorothy Parker, Alan Campbell, Walter Wanger, Dashiell Hammett, Donald Ogden Stewart, John Howard Lawson, Clifford Odets, John Bright, Dudley Nichols, Frederic March, Lewis Milestone, Oscar Hammerstein II, Ernst Lubitsch, Mervyn LeRoy, Gloria Stuart, Sylvia Sidney, F. Scott Fitzgerald, Chico Marx, Benny Goodman, Fred MacMurray and Eddie Cantor. Another member, Philip Dunne, later admitted "I joined the Anti-Nazi League because I wanted to help fight the most vicious subversion of human dignity in modern history".

In 1937 Belfrage joined the American Communist Party, but withdrew his membership a few months later. He was too much a political maverick to accept the discipline of the party. For example, at one meeting, John Bright, asked Victor Jerome, the leading party member in Hollywood: "Comrade Jerome, what if a Party decision is made that you cannot go along with?" Jerome replied: "When the Party makes a decision, it becomes your opinion."

Belfrage became active in the fight against fascism and developed a close relationship with Victor Gollancz and the Left Book Club. He wrote several books during this period on politics. This included Away From It All (1937), Promised Land (1937), Let My People Go (1937) and South of God (1938). Belfrage was passionate about what his son described as the "plight of humanity". Nicholas Belfrage later argued: "He fought all the time against oppression, privilege, injustice, all that. He never gave a damn about material things or money, which meant that it fell to my poor mother to support and look after the family with very little help."

Ruth Dudley Edwards, the author of Victor Gollancz: A Biography (1987) has commented: "Belfrage, the author of the February 1938 choice (of the Left Book Club) Promised Land, an inner history of Hollywood - showing what happened to art under capitalism." Edwards quotes Belfrage as saying that at one packed meeting at the Empress Hall, which seated 11,000, he found the occasion "the atmosphere of a true religious revival".

In June, 1940, Winston Churchill appointed William Stephenson as the head of the British Security Coordination (BSC). Stewart Menzies, head of MI6, sent a message to Gladwyn Jebb, of the Ministry of Economic Warfare: "I have appointed Mr W.S. Stephenson to take charge of my organisation in the USA and Mexico. As I have explained to you, he has a good contact with an official who sees the President daily. I believe this may prove of great value to the Foreign Office in the future outside and beyond the matters on which that official will give assistance to Stephenson. Stephenson leaves this week. Officially he will go as Principal Passport Control Officer for the USA. I feel that he should have contact with the Ambassador, and should like him to have a personal letter from Cadogan to the effect that it may at times be desirable for the Ambassador to have personal contact with Mr Stephenson."

As William Boyd has pointed out: "The phrase (British Security Coordination) is bland, almost defiantly ordinary, depicting perhaps some sub-committee of a minor department in a lowly Whitehall ministry. In fact BSC, as it was generally known, represented one of the largest covert operations in British spying history... With the US alongside Britain, Hitler would be defeated - eventually. Without the US (Russia was neutral at the time), the future looked unbearably bleak... polls in the US still showed that 80% of Americans were against joining the war in Europe. Anglophobia was widespread and the US Congress was violently opposed to any form of intervention."

An office was opened in the Rockefeller Centre in Manhattan with the agreement of President Franklin D. Roosevelt and J. Edgar Hoover of the FBI. Roosevelt's top security advisor, Adolph Berle, sent a message to Sumner Welles, the Under Secretary of State: "The head of the field service appears to be Mr. William S. Stephenson... in charge of providing protection for British ships, supplies etc. But in fact a full size secret police and intelligence service is rapidly evolving... with district officers at Boston, New York City, Philadelphia, Baltimore, Charleston, New Orleans, Houston, San Francisco, Portland and probably Seattle.... I have in mind, of course, that should anything go wrong at any time, the State Department would be called upon to explain why it permitted violation of American laws and was compliant about an obvious breach of diplomatic obligation... Were this to occur and a Senate investigation should follow, we should be on very dubious ground if we have not taken appropriate steps."

An important British agent, Charles Howard Ellis, was sent to New York City to work alongside William Stephenson as assistant-director. Together they recruited several businessmen, journalists, academics and writers into the BSC. This included Roald Dahl, H. Montgomery Hyde, Ian Fleming, Ivar Bryce, David Ogilvy, Isaiah Berlin, Eric Maschwitz, A. J. Ayer, Giles Playfair, Benn Levy, Noël Coward and Gilbert Highet.

Cedric Belfrage joined the BSC in December 1941. According to William Deaken, one of the senior figures in the organisation: "Belfrage was brought in as one of the propaganda people... he was a known communist." He was recruited by the BSC because if his contacts with American journalists. The strategy was to work with American journalists to persuade them to write articles that would advocate intervention in the Second World War.

Belfrage worked with organizations such as the Committee to Defend America by Aiding the Allies (CDAAA) that had been founded by William Allen White. He gave an interview to the Chicago Daily News where he argued: "Here is a life and death struggle for every principle we cherish in America: For freedom of speech, of religion, of the ballot and of every freedom that upholds the dignity of the human spirit... Here all the rights that common man has fought for during a thousand years are menaced... The time has come when we must throw into the scales the entire moral and economic weight of the United States on the side of the free peoples of Western Europe who are fighting the battle for a civilized way of life."

According to William Boyd: "BSC's media reach was extensive: it included such eminent American columnists as Walter Winchell and Drew Pearson, and influenced coverage in newspapers such as the Herald Tribune, the New York Post and the Baltimore Sun. BSC effectively ran its own radio station, WRUL, and a press agency, the Overseas News Agency (ONA), feeding stories to the media as they required from foreign datelines to disguise their provenance. WRUL would broadcast a story from ONA and it thus became a US "source" suitable for further dissemination, even though it had arrived there via BSC agents. It would then be legitimately picked up by other radio stations and newspapers, and relayed to listeners and readers as fact. The story would spread exponentially and nobody suspected this was all emanating from three floors of the Rockefeller Centre. BSC took enormous pains to ensure its propaganda was circulated and consumed as bona fide news reporting. To this degree its operations were 100% successful: they were never rumbled."

Roald Dahl was assigned to work with Drew Pearson, one of America's most influential journalist as the time. "Dahl described his main function with BSC as that of trying to 'oil the wheels' that often ground imperfectly between the British and American war efforts. Much of this involved dealing with journalists, something at which he was already skilled. His chief contact was the mustachioed political gossip columnist Drew Pearson, whose column, Washington Merry-Go-Round, was widely regarded as the most important of its kind in the United States."

After the bombing of Pearl Harbor in December 1941, much of the BSC's security and intelligence work could legitimately be taken over the FBI and other United States agencies. William Stephenson told Stewart Menzies, head of MI6, that the very existence of the BSC was now threatened. In January 1942, the McKellar Bill was before Congress, requiring the registration of all "foreign agents". Stephenson told Menzies this "might render work of this office in U.S.A. impossible as it is obviously inadmissible that all our records and other material should be made public". After some vigorous lobbying by Stephenson and others, the McKellar Bill was amended so that agents of the Allied "United Nations" would be exempt from registration and need only report in private to their own embassy.

BSC agents now worked very closely with the FBI. Belfrage was asked to infiltrate a Soviet network run by Jacob Golos. He was the most important Soviet agent in the United States. Golos had been recruited by Gaik Ovakimyan, the NKVD station chief in New York City. Secret Soviet intelligence cables from Golos as "our reliable man in the U.S." According to Allen Weinstein, the author of The Hunted Wood: Soviet Espionage in America (1999): "Through bribes, Golos developed a network of foreign consular officials and U.S. passport agency workers who supplied him not only with passports but also naturalization documents and birth certificates belonging to persons who had died or had permanently left the United States."

The FBI became aware that Golos was running a travel agency, World Tourists in New York City, as a front for Soviet clandestine work. His office was raided by officials of the Justice Department. Some of these documents showed that Earl Browder, the leader of the Communist Party of the United States, had travelled on a false passport. Browder was arrested and Golos told Elizabeth Bentley: "Earl is my friend. It is my carelessness that is going to send him to jail." Bentley later recalled that the incident took its toll on Golos: "His red hair was becoming grayer and sparser, his blue eyes seemed to have no more fire in them, his face became habitually white and taut."

The FBI decided that he was worth more to them free than in prison. According to Bentley, United States officials agreed to drop the whole investigation, if Golos pleaded guilty. He told her that Moscow insisted that he went along with the deal. "I never thought that I would live to see the day when I would have to plead guilty in a bourgeois court." He complained that they had forced him to become a "sacrificial goat". On 15th March, 1940, Golos received a $500 fine and placed on four months probation.

On 18th January, 1941, the FBI saw Golos exchange documents with Gaik Ovakimyan. The FBI also observed Golos meeting Elizabeth Bentley at the offices of the of the U.S. Service and Shipping Corporation. The agents wondered if she might be a Soviet spy as well and she was followed. On 23rd May, 1941, Ovakimyan was arrested and deported.

He later explained to the FBI that under orders from BSC he had passed files to Russian contacts during the war in order to get material back in return. "My thought was to tell him certain things of a really trifling nature from the point of view of British and American interest, hoping in this way to get from him some more valuable information from the Communist side."

The Soviets gave Cedric Belfrage the code-name, UCN/9. He was also known as "MOLLY". We know about this because of the declassifed Venona files. After the war a team led by Meredith Gardner was assigned to help decode a backlog of communications between Moscow and its foreign missions. By 1945, over 200,000 messages had been transcribed and now a team of cryptanalysts attempted to decrypt them. The project, named Venona (a word which appropriately, has no meaning), was based at Arlington Hall, Virginia.

It was not until 1949 that Gardner made his big breakthrough. He was able to decipher enough of a Soviet message to identify it as the text of a 1945 telegram from Winston Churchill to Harry S. Truman. Checking the message against a complete copy of the telegram provided by the British Embassy, the cryptanalysts confirmed beyond doubt that during the war the Soviets had a spy who had access to secret communication between the president of the United States and the prime minister of Britain.

Meredith Gardner and his team were able to work out that more than 200 Americans had become Soviet agents during the Second World War. They had spies in the State Department and most leading government agencies, the Manhattan Project and the Office of Strategic Services (OSS). This included Elizabeth Bentley, Marion Bachrach, Joel Barr, Abraham Brothman, Earl Browder, Karl Hermann Brunck, Louis Budenz, Whittaker Chambers, Frank Coe, Henry Hill Collins, Judith Coplon, Lauchlin Currie, Hope Hale Davis, Samuel Dickstein, Martha Dodd, Laurence Duggan, Gerhart Eisler, Noel Field, Harold Glasser, Vivian Glassman, Jacob Golos, Theodore Hall, Alger Hiss, Donald Hiss, Joseph Katz, Charles Kramer, Duncan Chaplin Lee, Harvey Matusow, Hede Massing, Paul Massing, Boris Morros, William Perl, Victor Perlo, Joszef Peter, Lee Pressman, Mary Price, Joseph North, William Remington, Alfred Sarant, Abraham George Silverman, Helen Silvermaster, Nathan Silvermaster, Alfred Stern, William Ludwig Ullmann, Julian Wadleigh, Harold Ware, Nathaniel Weyl, Donald Niven Wheeler, Harry Dexter White, Nathan Witt and Mark Zborowski.

These agents were never prosecuted because the FBI and the CIA did not want the Soviets to know they had broken their code. However, the Soviets knew as early as 1949 because one of Gardner's assistants, William Weisband, was also a Soviet agent. To make sure that the FBI was unaware that they knew that the code was about to be broken, they continued to use it. The "operatives" were instructed "every week to compose summary reports or information on the basis of press and personal connections to be transferred to the Center by telegraph." As Allen Weinstein, the author of The Hunted Wood: Soviet Espionage in America (1999) has pointed out the "Soviet intelligence's once-flourishing American networks, in short, had been transformed almost overnight into a virtual clipping service."

Ever since the Soviet Union had entered the war, Joseph Stalin had been demanding that the Allies open-up a second front in Europe. Winston Churchill and Franklin D. Roosevelt argued that any attempt to land troops in Western Europe would result in heavy casualties. Stalin began to worry that the Allies wanted Adolf Hitler to destroy Soviet communism. It was important for Stalin to be convinced that a Second Front would eventually be achieved.

Cedric Belfrage was part of this project. In 1995-96 over 2,990 fully or partially decrypted Soviet intelligence cables from the Venona archives were declassified and released by the Central Intelligence Agency and the National Security Agency. This included cables that concerned Belfrage. One dated 19th May, 1943, from Vassili Zarubin stated that UCN/9, had informed them that there was a "growing movement" for "opening a second front in Europe".

This information about the desire for a Second Front had been obtained by BSC agent, David Ogilvy, who worked for the Audience Research Institute, that had been set-up by George H. Gallup and Hadley Cantril. According to the official BSC history, from later 1941 on Ogilvy was "able to ensure a constant flow of intelligence on public opinion in the United States, since he had access not only to the questionnaires sent out by Gallup and Cantril and to the recommendations offered by the latter to the White House," but also to "internal reports prepared by the Survey Division of the Office of War Information and by the Opinion Research Division of the U.S. Army". (28)

According to Robert J. Lamphere, a member of the Soviet Espionage unit of the FBI, who was involved in interviewing Elizabeth Bentley, reports that she claims that Belfrage passed to Golos a "Scotland Yard secret instruction manual on the training of British Intelligence agents".

It is also clear that since joining the British Security Coordination (BSC) in December 1941, Belfrage had not told the Soviets of the existence of the organisation. In June, 1943, Pavel Klarin, the Soviet vice-counsul in New York City, and a senior NKVD officer, was requested to investigate the existence of this organization. On 21st June he replied: "The organization 'British Security Coordination' is not known to us. We have taken steps to find out what it is. We will report the result in the next few days."

By this time Jacob Golos was having doubts about Belfrage. His assistant, Elizabeth Bentley, later told the FBI "Belfrage was an extremely odd character, and rather difficult to deal with. Although passionately devoted to the cause, he still considered himself a patriotic Britisher, and hence he would give us no information that showed up England's mistakes or tended to make her a laughing-stock."

In September 1943, Golos broke off contact with Cedric Belfrage. The official reason was that Golos had shown some of the material provided by Belfrage to Earl Browder. He had used some of this information in an article that he had written for an article that appeared in a magazine controlled by the Communist Party of the United States. Terrified that the FBI might trace the source of the leak, the Soviets decided to have nothing more to do with Belfrage. However, the real reason is that another Soviet agent, HAVRE (the true identity of this agent has never been discovered), had reported that Belfrage had failed to give Golos details about the BSC. This suggested to the Soviets he was working as a double agent.

Belfrage also co-edited a left literary magazine, The Clipper, during the Second World War. In the magazine he promoted the work of Orson Welles. According to the authors of Radical Hollywood (2002), he selected Citizen Kane "as the supreme example of what radical innovators could do in Hollywood, the proof that showed the way forward." Belfrage argued that the movie was "as profoundly moving an experience as only this extraordinary and hitherto unexplored media of sound-cinema can afford." Belfrage suggested that progressive figures in Hollywood had been"hoping and trying for a chance like this.... but always the film salesman, speaking through the producer, has the last word."

In 1944 Belfrage worked at the "Psychological Warfare Division" of Supreme Headquarters Allied Expeditionary Force (SHAEF) in Paris under the direct control of General Dwight D. Eisenhower. Belfrage was involved in setting up a free and democratic press in West Germany. As Belfrage pointed out, at last "albeit kicking and screaming, democratic capitalism had joined with Soviet socialism to wipe from the earth the war virus in the most pestilent form - fascism." Belfrage welcomed the new power he had been given. "We were part inquisitors, part entrepreneurs but with privileges denied to a Beaverbrook or Hearst. Waving the conqueror's wand, we simply requisitioned real estate, materials, and equipment for use by the new "democratic" press we were required to create." In late 1945 General Eisenhower told him in a telegram that it was not considered right to employ someone who was "British" in what had become an "American zone" and he returned to the United States.

In 1948 Belfrage helped establish the National Guardian with James Aronson and John T. McManus. (45) The newspaper provided positive publicity for Vito Marcantonio and the American Labor Party (ALP). The newspaper also campaigned against the convictions of Julius Rosenberg and Ethel Rosenberg. One of its journalists, William A. Reuben, who wrote many of the articles on the case, later published The Atom Spy Hoax (1954) on the Rosenbergs.

Robert J. Lamphere later reported that Belfrage's campaign against the proposed execution of the Rosenberg's upset the FBI: "The important thing was that the Reuben articles provided the fodder for a concerted campaign to make the public believe not only that the Rosenbergs were framed but also the United States government was guilty of murdering innocent Jewish idealists. This campaign was ultimately of great benefit to the Soviet Union."

On his return to the United States he was approached by the journalist, Joseph North, to rejoin the Communist Party of the United States. Belfrage rejected the idea as he had opposed the party's support of the Nazi-Soviet Pact and the way it had purged members for not supporting the policy of Joseph Stalin. Instead he joined the Progressive Party, led by Henry A. Wallace. He admitted that Wallace was "too capitalist for our heartiest cheers" but felt he could provide a "political home" for his socialist beliefs.

On 6th May 1953 Belfrage was summoned to appear before the House Un-American Activities Committee (HCUA). According to Glenn Fowler, of The New York Times, the main reason for this was for his work in the "Psychological Warfare Division" in West Germany. Belfrage and James Aronson were accused of having approved "Communists to publish newspapers".

His son, Nicholas Belfrage, later recalled: "One morning I heard on the radio that the band leader Artie Shaw and the journalist Cedric Belfrage were to appear that day before HUAC. I knew it was coming but I was terrified nonetheless, because at that time there was a general atmosphere of fear and I thought I stood a good chance of being beaten up at my Bronx school or at least ostracised by my friends. In the event none of my contemporaries ever mentioned it, though my teacher, one Bessie Coyne whose adoration for McCarthy was matched only by her loathing of Communists and Brits (I was deemed to be both) inquired of me before a packed and silent class: 'Who are you going to kill today, Belfrage?' I was 13 at the time."

Belfrage refused to answer questions put to him by Harold H. Velde because "whatever answers I would give would be used to crucify me and other innocent persons". Another HUAC member, Bernard W. Kearney, told Belfrage: "I'm going to contact immigration authorities and find out why you are still in this country. I think you're the type to be deported immediately."

Belfrage later argued that Joseph McCarthy and Roy Cohn were determined to bring an end to the National Guardian as it was one of his major critics. "McCarthy struck red gold: two subversive army officers who, after laboring to create a 'red press' in Germany, had returned to establish one at home - a paper now leading the fight for the Rosenbergs, at whose trial Cohn had been an assistant prosecutor."

Later that month Belfrage was arrested and taken to Ellis Island, at that time, the immigration detention centre. On 10th June, 1953, he was freed by Federal District Judge Edward Weinfeld. In a statement issued by Weinfeld he argued: "If for the long period of seven years following... the immigration and other government officials did not consider Belfrage's presence and activities inimical to the nation's welfare and a threat to its security, it is difficult to understand how, overnight, because of his assertion of a constitutional privilege, he has become such a menace to the nation's safety that it is now necessary to jail him without bail."

Cedric Belfrage was eventually deported on 15th August 1955. "America banished one of its most devoted sons last week in the person of Cedric Henning Belfrage, editor of the newspaper. With his wife, the Guardian editor sailed at noon, Monday, August 15, on the Holland-America liner Nieuw Amsterdam for his native England under a deportation order demanded 27 months ago by Senator Joseph McCarthy." The following year Belfrage published The Frightened Giant: My Unfinished Affair with America (1956).

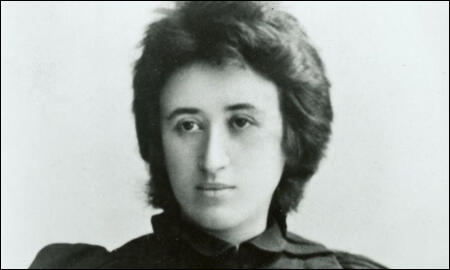

On this day in 1918, anti-war activist, Rosa Luxemburg, is released from prison in Breslau. She went to Cathedral Square, in the centre of the city, where she was cheered by a mass demonstration. Two days later she arrived in Berlin. Her appearance shocked her friends in the Spartacus League: "They now saw what the years in prison had done to her. She had aged, and was a sick woman. Her hair, once deep black, had now gone quite grey. Yet her eyes shone with the old fire and energy."

Friedrich Ebert established the Council of the People's Deputies, a provisional government consisting of three delegates from the Social Democratic Party (SPD) and three from the Independent Social Democratic Party (USPD). Liebknecht was offered a place in the government but he refused, claiming that he would be a prisoner of the non-revolutionary majority. A few days later Ebert announced elections for a Constituent Assembly to take place on 19th January, 1918. Under the new constitution all men and women over the age of 20 had the vote.

As a believer in democracy, Rosa Luxemburg assumed that her party, the Spartacus League, would contest these universal, democratic elections. However, other members were being influenced by the fact that Lenin had dispersed by force of arms a democratically elected Constituent Assembly in Russia. Luxemburg rejected this approach and wrote in the party newspaper: "The Spartacus League will never take over governmental power in any other way than through the clear, unambiguous will of the great majority of the proletarian masses in all Germany, never except by virtue of their conscious assent to the views, aims, and fighting methods of the Spartacus League."

Luxemburg was aware that the Spartacus League only had 3,000 members and not in a position to start a successful revolution. The Spartacus League consisted chiefly of innumerable small and autonomous groups scattered all over the country. John Peter Nettl has argued that "organisationally Spartacus was slow to develop... In the most important cities it evolved an organised centre only in the course of December... and attempts to arrange caucus meetings of Spartakist sympathisers within the Berlin Workers' and Soldiers' Council did not produce satisfactory results."

Pierre Broué suggests that the large meetings helped to convince Karl Liebknecht that a successful revolution was possible. "Liebknecht, an untiring agitator, spoke everywhere where revolutionary ideas could find an echo... These demonstrations, which the Spartakists had neither the force nor the desire to control, were often the occasion for violent, useless or even harmful incidents caused by the doubtful elements who became involved in them... Liebknecht could have the impression that he was master of the streets because of the crowds which acclaimed him, while without an authentic organisation he was not even the master of his own troops."

A convention of the Spartacus League began on 30th December, 1918. Karl Radek, a member of the Bolshevik Central Committee, argued that the the Soviet government should help the spread of world revolution. Radek was sent to Germany and at the convention he persuaded the delegates to change the name to the German Communist Party (KPD). The convention now discussed whether the KPD should take part in the forthcoming general election.

Rosa Luxemburg, Paul Levi and Leo Jogiches all recognised that a "successful revolution depended on more than temporary support for certain slogans by a disorganised mass of workers and soldiers". As Rosa Levine-Mayer explained the election "had the advantage of bringing the Spartacists closer to the broader masses and acquainting them with Communist ideas. Nor could a set-back, followed by a period of illegality, even if only temporary, be altogether ruled out. A seat in the Parliament would then be the only means of conducting Communist propaganda openly.It could also be foreseen that the workers at large would not understand the idea of a boycott and would not be persuaded to stay aloof; they would only be forced to vote for other parties."

Luxemburg, Levi and Jogiches and other members who wanted to take part in elections were outvoted on this issue. As Bertram D. Wolfe has pointed out: "In vain did she (Luxemburg) try to convince them that to oppose both the Councils and the Constituent Assembly with their tiny forces was madness and a breaking of their democratic faith. They voted to try to take power in the streets, that is by armed uprising."

On this day in 1923, Adolf Hitler instigates the Beer Hall Putsch. On 8th November, 1923, the Bavarian government held a meeting of about 3,000 officials. While Gustav von Kahr, the prime minister of Bavaria was making a speech, Adolf Hitler and 600 armed SA men entered the building. According to Ernst Hanfstaengel: "Hitler began to plough his way towards the platform and the rest of us surged forward behind him. Tables overturned with their jugs of beer. On the way we passed a major named Mucksel, one of the heads of the intelligence section at Army headquarters, who started to draw his pistol as soon as he saw Hitler approach, but the bodyguard had covered him with theirs and there was no shooting. Hitler clambered on a chair and fired a round at the ceiling." Hitler then told the audience: "The national revolution has broken out! The hall is filled with 600 armed men. No one is allowed to leave. The Bavarian government and the government at Berlin are hereby deposed. A new government will be formed at once. The barracks of the Reichswehr and the police barracks are occupied. Both have rallied to the swastika!"

Leaving Hermann Göring and the SA to guard the 3,000 officials, Hitler took Gustav von Kahr, Otto von Lossow, the commander of the Bavarian Army and Hans von Seisser, the commandant of the Bavarian State Police into an adjoining room. Hitler told the men that he was to be the new leader of Germany and offered them posts in his new government. Aware that this would be an act of high treason, the three men were initially reluctant to agree to this offer. Adolf Hitler was furious and threatened to shoot them and then commit suicide: "I have three bullets for you, gentlemen, and one for me!" After this the three men agreed to become ministers of the government.

On this day in 1938 Crystal Bird Fauset became the first Black woman to serve in a state legislature. She served for a year as a state representative in which she introduced nine bills and three amendments on issues ranging from affordable housing projects to fair employment legislation. She also worked under Franklin D. Roosevelt as a race relations advisor.

On this day in 1965 Dorothy Kilgallen, American journalist was murdered. John F. Kennedy was assassinated in Dallas, Texas, on 22nd November, 1963. Kilgallen took a keen interest in the case and soon became convinced that Kennedy had not been killed by Lee Harvey Oswald. Kilgallen had a good contact within the Dallas Police Department. He gave her a copy of the original police log that chronicled the minute-by-minute activities of the department on the day of the assassination, as reflected in the radio communications. This enabled her to report that the first reaction of Chief Jesse Curry to the shots in Dealey Plaza was: "Get a man on top of the overpass and see what happened up there". Kilgallen pointed out that he lied when he told reporters the next day that he initially thought the shots were fired from the Texas Book Depository.

Kilgallen also had a source within the Warren Commission. This person gave her an 102 page segment dealing with Jack Ruby before it was published. She published details of this leak and so therefore ensuring that this section appeared in the final version of the report. The Federal Bureau of Investigation investigated the leak and on 30th September, 1964, Kilgallen reported in the New York Journal American that the FBI "might have been more profitably employed in probing the facts of the case rather than how I got them".

In another of her stories, Kilgallen claimed that Marina Oswald knew a great deal about the assassination of John F. Kennedy. If she told the "whole story of her life with President Kennedy's alleged assassin, it would split open the front pages of newspapers all over the world."

Kilgallen's reporting brought her into contact with Mark Lane who had himself received an amazing story from the journalist Thayer Waldo. He had discovered that Jack Ruby, J. D. Tippet and Bernard Weismann had a meeting at the Carousel Club eight days before the assassination. Waldo, who worked for the Fort Worth Star-Telegram, was too scared to publish the story. He had other information about the assassination. However, he believed that if he told Lane or Kilgallen he would be killed. Kilgallen's article on the Tippit, Ruby and Weissman meeting appeared on the front page of the Journal American. Later she was to reveal that the Warren Commission were also tipped off about this gathering. However, their informant added that there was a fourth man at the meeting, an important figure in the Texas oil industry.

Kilgallen published several articles about how important witnesses had been threatened by the Dallas Police or the FBI. On 25th September, 1964, Kilgallen published an interview with Acquilla Clemons, one of the witnesses to the shooting of J. D. Tippet. In the interview Clemons told Kilgallen that she saw two men running from the scene, neither of whom fitted Oswald's description. Clemons added: "I'm not supposed to be talking to anybody, might get killed on the way to work."

Kilgallen was keen to interview Jack Ruby. She went to see Ruby's lawyer Joe Tonahill and claimed she had a message for his client from a mutual friend. It was only after this message was delivered that Ruby agreed to be interviewed by Kilgallen. Tonahill remembers that the mutual friend was from San Francisco and that he was involved in the music industry. Kennedy researcher, Greg Parker, has suggested that the man was Mike Shore, co-founder of Reprise Records.

The interview with Ruby lasted eight minutes. No one else was there. Even the guards agreed to wait outside. Officially, Kilgallen never told anyone about what Ruby said to her during this interview. Nor did she publish any information she obtained from the interview. There is a reason for this. Kilgallen was in financial difficulties in 1964. This was partly due to some poor business decisions made by her husband, Richard Kollmar. The couple had also lost the lucrative contract for their radio show Breakfast with Dorothy and Dick. Kilgallen also was facing an expensive libel case concerning an article she wrote about Elaine Shepard. Her financial situation was so bad she fully expected to lose her beloved house in New York City.

Kilgallen was a staff member of Journal American. Any article about the Jack Ruby interview in her newspaper would not have helped her serious financial situation. Therefore she decided to include what she knew about the assassination of John F. Kennedy in Murder One. She fully expected that this book would earn her a fortune. This is why she refused to tell anyone, including Mark Lane, about what Ruby told her in the interview arranged by Tonahill. In October, 1965, told Lane that she had a new important informant in New Orleans.

Kilgallen began to tell friends that she was close to discovering who assassinated Kennedy. According to David Welsh of Ramparts Magazine Kilgallen "vowed she would 'crack this case.' And another New York show biz friend said Dorothy told him in the last days of her life: "In five more days I'm going to bust this case wide open." Aware of what had happened to Bill Hunter and Jim Koethe, Kilgallen handed a draft copy of her chapter on the assassination to her friend, Florence Smith.

On 8th November, 1965, Kilgallen, was found dead in her New York apartment. She was fully dressed and sitting upright in her bed. The police reported that she had died from taking a cocktail of alcohol and barbiturates. The notes for the chapter she was writing on the case had disappeared. Her friend, Florence Smith, died two days later. The copy of Kilgallen's article were never found.

Some of her friends believed Kilgallen had been murdered. Marc Sinclaire was Kilgallen's personal hairdresser. He often woke Kilgallen in the morning. Kilgallen was usually out to the early hours of the morning and like her husband always slept late. When he found her body he immediately concluded she had been murdered.

(1) Kilgallen was not sleeping in her normal bedroom. Instead she was in the master bedroom, a room she had not occupied for several years.

(2) Kilgallen was wearing false eyelashes. According to Sinclaire she always took her eyelashes off before she went to bed.

(3) She was found sitting up with the book, The Honey Badger, by Robert Ruark, on her lap. Sinclaire claims that she had finished reading the book several weeks earlier (she had discussed the book with Sinclaire at the time).

(4) Kilgallen had poor eyesight and could only read with the aid of glasses. Her glasses were not found in the bedroom where she died.

(5) Kilgallen was found wearing a bolero-type blouse over a nightgown. Sinclaire claimed that this was the kind of thing "she would never wear to go to bed".

Mark Lane also believed that Kilgallen had been murdered. He said that "I would bet you a thousand-to-one that the CIA surrounded her (Kilgallen) as soon as she started writing those stories." The only new person who became close to Kilgallen during the last few months was her new secret lover. In her book, Lee Israel, in her book, Kilgallen (1979) calls him the "Out-of-Towner".

According to Israel she met him in Carrara in June, 1964, during a press junket for journalists working in the film industry. The trip was paid for by Twentieth Century-Fox who used it to publicize three of its films: The Sound of Music, The Agony and the Ecstasy and Those Magnificent Men in Their Flying Machines. Israel claims that the "Out-of-Towner" went up to Kilgallen and asked her if she was Clare Booth Luce. This is in itself an interesting introduction. Kilgallen and Luce did not look like each other. Luce and her husband (Henry Luce) however were to play an important role in the events surrounding the assassination. Luce owned Life Magazine and arranged to buy up the Zapruder Film . Clare Booth Luce had also funded covert operations against Fidel Castro (1961-63).

Lee Israel originally refused to identify the "Out-of-Towner". In 1993 the investigative reporter, David Herschel, discovered that his real name was Ron Pataky. In 1965 he had been a journalist working for the Columbus Citizen-Journal. He admitted that he was the "Out-of-Towner" and that he worked on articles about the assassination of John F. Kennedy with Kilgallen. Pataky also confessed to meeting Kilgallen several times in the Regency Hotel. However, he denied Lee Israel's claim that he was with her on the night of her death.

In December, 2005, Lee Israel admitted that the "Out-of-Towner" was Ron Pataky and that "he had something to do with it (the murder of Dorothy Kilgallen)".

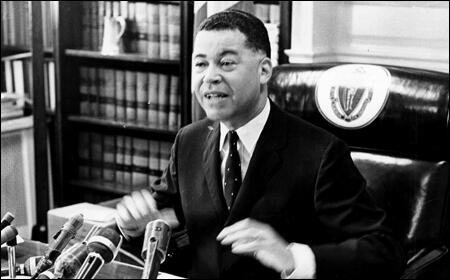

On this day in 1966 Edward Brooke becomes the first African American elected to the United States Senate since Reconstruction. Brooke worked as a lawyer in Boston before becoming Massachusetts attorney general (1963-66). In the Senate he campaigned for for low-income public housing projects. Brooke served in the Senate for twelve years before being defeated in 1978.

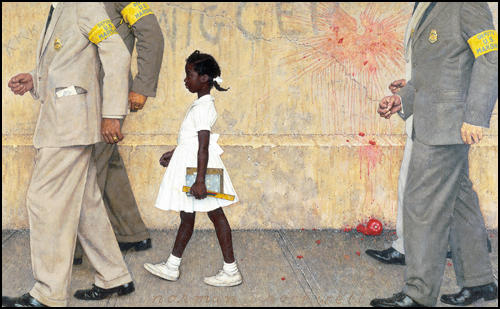

On this day in 1978 Norman Rockwell, American illustrator died. Rockwell held fairly conservative views until the death of John F. Kennedy convinced him to join Look Magazine, as a commentator of current affairs. Rockwell's first double-page illustration for the magazine, The Problem We All Live With (14th January, 1964) was one of his most memorable paintings. It shows Ruby Bridges, who in 1960, when she was 6 years old, became involved in the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) campaign to integrate the New Orleans School system. When she entered William Frantz Elementary School in 1960 she became the first African-American child to attend an all-white elementary school in the South.