Victor Jerome

Jerome Isaac Romain was born in Stryków, Poland in 1896. He was sent to London before moving to New York City in 1915. (1) Romain attended the City College of New York. After leaving college he worked as a bookkeeper for the International Ladies' Garment Workers Union. During this period he adopted the name Victor Jerome (V. J. Jerome). Eugene Lyons described him during this period as a "studious, idealistic, likeable young man." (2)

In September 1919, Jerome joined forces with Jay Lovestone, Earl Browder, John Reed, James Cannon, Bertram Wolfe, William Bross Lloyd, Benjamin Gitlow, Charles Ruthenberg, Mikhail Borodin, William Dunne, Elizabeth Gurley Flynn, Louis Fraina, Ella Reeve Bloor, Rose Pastor Stokes, Juliet Poyntz, Nathan Silvermaster, Jacob Golos, Claude McKay, Max Shachtman, Martin Abern, Michael Gold and Robert Minor, to form the Communist Party of the United States (CPUS).

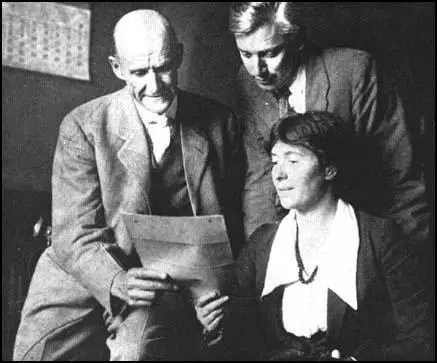

Victor Jerome & Rose Pastor Stokes

Jerome married the Italian writer, Francis Vinciguerra (also known as Frances Winwar) in about 1920. They had a son named Germinal but the marriage ended in divorce. In 1925 he became involved with Rose Pastor Stokes. At the time he was twenty-nine and she was forty-seven. (3) Stokes wrote to Jeanette Pearl about the new man in her life: "I'm interfering with his studies and I'm afraid he's interfering with my peace of mind.... I'm mighty near being at that extent that I shall lose all sane judgment. Don't fall in love, Jean. It's an enslaver of life." (4) The couple married in February, 1927.

In 1929 Rose Pastor Stokes was seriously injured when clubbed by police at a demonstration demanding the withdrawal of U.S. forces from Haiti. According to a report in the Daily Chronicle Rose Pastor Stokes "was struck while attempting to protect a young boy from a policeman". (5)

According to Judith Rosenbaum: "In 1930, Stokes was diagnosed with a malignant breast tumor, which she attributed to having received a blow on the breast from a policeman’s club during a demonstration - claiming martyrdom for the proletarian cause. Her health rapidly declined; even so, she maintained her radical, fighting spirit. Although her illness prevented her from remaining active in the Communist Party during the last years of her life, she continued to assert her allegiance to it." Rose moved to Germany to have radiation therapy but died in Frankfurt on 20th June, 1933. (6)

Party's Cultural Commission

In 1935 Victor Jerome became the editor of the Party's theoretical journal, The Communist. The following year he became the head of the Party's Cultural Commission. For a time, Jerome personally assumed responsibility for the Hollywood branches, "insulating them from the rest of the Party in Los Angeles and keeping them in direct touch with the national leadership". (7)

Hollywood stars who were sympathetic to communism were seen as a source of financial support for the Communist Party of the United States. It also offered the chance to influence or control "the weapon of mass culture". A young screenwriter, John Howard Lawson ran the Hollywood branch. (8) However, as Victor Navasky, the author of Naming Names (1982) pointed out: "John Howard Lawson, who ran the Hollywood branch, quickly understood that the collective process of movie making precluded the screenwriter, low man on the creative totem pole, from influencing the content of movies." (9)

Jerome was used to defend the actions of Joseph Stalin. He spent a lot of time in Hollywood in the 1930s explaining the Moscow Show Trials, which resulted in the executions of leading figures such as Gregory Zinoviev, Lev Kamenev, Yuri Piatakov, Karl Radek, Grigori Sokolnikov, Nickolai Bukharin, Alexei Rykov, Genrikh Yagoda, Nikolai Krestinsky and Christian Rakovsky. (10)

This caused problems for Jerome as many of its Hollywood members supported the Leon Trotsky wing of the party. Others were independent Marxists. The journalist, Cedric Belfrage, was one of those who objected to Jerome's pro-Stalin views. For example, at one meeting, John Bright, the screenwriter, asked Jerome: "Comrade Jerome, what if a Party decision is made that you cannot go along with?" Jerome replied: "When the Party makes a decision, it becomes your opinion." (11)

Granville Hicks later recalled submitted a book review for the Daily Worker where he claimed that Karl Marx and Lenin were great theoreticians. Jerome contacted Hicks and pointed out that he should have included Joseph Stalin in his list of "great theoreticians". Hicks refused and left the Communist Party. (12)

Victor Jerome also tried to influence those working in the theatre in New York City. One of the great successes during the 1930s was the Group Theatre that was formed by Harold Clurman, Cheryl Crawford and Lee Strasberg. The founders were not members of the party but some of the people involved in its activities were committed communists. This included Clifford Odets, who had great success with his plays Waiting for Lefty and Awake and Sing! in 1935.

Elia Kazan, a member of the group was later to complain about how they had been instructed to change a play so as to ridicule, Fiorello LaGuardia, the liberal mayor of New York City. In 1935 Kazan was asked by Jerome to arrange for the communists to take control of the institution: "I carried Comrade Jerome's message back to our regular Tuesday night meeting in Joe Bromberg's dressing room, passed on his instruction that our cell should immediately work to transform the Group into a collective, a theatre run by its actors. It was a surprise to me when the members of our cell quickly and unanimously did what the Theatre of Action people had done in the matter of the La Guardia play - give in to the political directive from the man on Twelfth Street. Then it was my turn to speak. I was timid; despite my present reputation as a bullheaded man, up until that time breaking ranks was an act of boldness for me. I surprised everyone by my recalcitrance; I surprised myself. I believe I sounded apologetic for disagreeing. I could feel bewilderment and impatience around me. I suppose the position I took was a sign of disrespect for my fellow actors' political savvy. And possibly their courage. They voted me down." (13)

Budd Schulberg was a novelist working in Hollywood. As a member of the Communist Party of the United States he was forced to show the manuscript of What Makes Sammy Run? to Victor Jerome, who disliked the book: "The feeling was that my book was a destructive idea; that... it was much too individualistic; that it didn't begin to show what were called the progressive forces in Hollywood." (14) Schulberg refused to change his book and instead left the party. (15)

Victor Jerome also became involved in a Soviet spy network based in the city that was run by Jacob Golos. Other members included Victor Perlo, Harry Dexter White, Nathan Silvermaster, Abraham George Silverman, Nathan Witt, Marion Bachrach, Julian Wadleigh, William Remington, Harold Glasser, Charles Kramer, Duncan Chaplin Lee, Joseph Katz, William Ludwig Ullmann, Henry Hill Collins, Frank Coe, Abraham Brothman, Mary Price and Lauchlin Currie. (16)

Cedric Belfrage, who was working as a double agent, told the FBI, that "I supplied him (Jerome) with information about Scotland Yard surveillances and also with some documents relative to the Vichy Government in France, which were of a highly confidential nature." (17) This was supported by the confession made by Elizabeth Bentley in 1945. (18)

Victor Jerome and Albert Maltz

On 12th February 1945, Albert Maltz wrote an article for the New Masses calling for more intellectual freedom in the Communist Party. "It has been my conclusion for some time that much of the left-wing artistic activity - both creative and critical - has been restricted, narrowed, tuned away from life, sometimes made sterile - because the atmosphere and thinking of the literary left-wing had been based upon a shallow approach... I have come to believe that the accepted understanding of art as a weapon is not a useful guide, but a straitjacket. I have felt this in my own works and viewed it in the works or others. In order to write at all, it has long since become necessary for me repudiate it and abandon it." (19)

Maltz went on to argue that it was wrong to judge creative works primarily by their ideology. He used the example of how a communist journal in 1940 attacking a play by Lillian Hellman, because its anti-Nazi politics were anathema during the period of the Nazi-Soviet Pact. (20)

Jerome organized the attack on Maltz. In the next edition of the New Masses, the novelist, Howard Fast, claimed: "He advocates, for the artist, retreat. He pleads with him to get out of the arena of life. The fact that life shows, and has shown for a generation now, that such retreat is tantamount to artistic death and personal degradation, cuts no ice with Maltz." (21) Joseph North wrote that Maltz would chop down "the fruitful tree of Marxism" to cure some weak branches. (22)

Alvah Bessie was another who criticised Maltz and suggested that what he said went against Marxism. "He (Maltz) nowhere states his frame of reference or identifies the point of departure from which he launches what is, objectively, not only an attack on Marxism but a defense of practically every renegade writer of recent years who ever flirted with the working-class movement... We need Party artists. We need artists deeply rooted in the working class." (23)

Other members such as Michael Gold, John Howard Lawson and William Z. Foster joined in. "Maltz, they insisted, had been taking dangerous liberties with the supremacy of political commitments over artistic tastes." (24) Lawson pointed out: "We cannot divorce the views expressed by Maltz from the historical moment he selects for the presentation of these views. He writes at a time of decisive struggle. The democratic victories achieved in the Second World War are threatened by the still powerful forces of imperialism and reaction, which are especially strong in the United States." (25)

Victor Jerome forced Maltz to write a retraction of his first article. On 9th April, 1946, two months after his initial effort, Albert Maltz published a second article in the New Masses: "I consider now that my article - by what I have come to agree was a one-sided, non-dialectical treatment of complex issues - could not... contribute to the development of left-wing criticism and creative writing." (26)

I. F. Stone later recalled he was appalled by the way Maltz was treated: "He (Jerome) is a hell of a nice guy personally but politically he has tried to ride hard on the intellectuals in a way most offensive to anyone who believes in intellectual and cultural freedom... often in most humiliating ways - as in the belly-crawl forced... on Albert Maltz... He (Jerome) has a dictatorial mentality." (27)

Howard Fast

In 1950 Howard Fast was ordered to appear before the House of Un-American Activities Committee. because he had contributed to the support of a hospital for Popular Front forces in Toulouse during the Spanish Civil War. When he appeared before the HUAC he refused to name fellow members of American Communist Party, claiming that the 1st Amendment of the United States Constitution gave them the right to do this. The HUAC and the courts during appeals disagreed and he was sentenced to three months in prison.

On his release from prison Fast discovered that Jerome had arranged the production of The Hammer. "During the weeks before going to prison, I had written a play called The Hammer. It was a drama about a Jewish family during the war years, a hard-working father who keeps his head just above water, and his three sons. One son comes out of the army, badly wounded, badly scarred. Another son makes a fortune out of the war, and the youngest son provides his share of the drama by deciding to enlist."

Fast went to see the pre-view of the play: "The play began. The father came onstage, Michael Lewin, small, slender, pale white skin, and orange hair. Nina Normani, playing Michael's wife, small, pale. The first son came onstage, James Earl Jones, six feet and two inches, barrel-cheated, eighteen years old if my memory serves me, two hundred pounds of bone and muscle if an ounce, and a bass voice that shook the walls of the little theater."

Fast complained about the casting of James Earl Jones as Jimmy Jones. He was told that it had all been arranged by Victor Jerome and that he was being a white chauvinist in objecting to the part played by a black actor. Fast replied: "I'm not being a white chauvinist, Lionel. But Mike here weighs in at maybe a hundred and ten pounds, and he's as pale as anyone can be and he's Jewish, and for God's sake, tell me what genetic miracle could produce Jimmy Jones." However, after threats that Jerome would have him expelled from the Communist Party he accepted the casting. (28)

National Guardian

Victor Jerome, as head of the Cultural Commission, controlled the content of the party's journals. He also attempted to influence other left-wing journals. After the war Cedric Belfrage, James Aronson and John T. McManus established the National Guardian. The newspaper provided positive publicity for Vito Marcantonio and the American Labor Party (ALP) and Henry A. Wallace and the Progressive Party.

According to Belfrage, Jerome attempted to take control of the newspaper via the men printing the papers: "V. J. Jerome was an outwardly mild man with a unique blend of the poetic with party-line austerity. I had little doubt that, if there was any scheme to take over the National Guardian through a staff communist cell, he would know all about it." At a meeting with Jerome he mentioned his past involvement with British intelligence. Fearing the possibility of being reported to the authorities, Jerome agreed to "call off his shock-troops". (29)

The Smith Act

In 1951 Victor Jerome was prosecuted under the Smith Act, for writing a pamphlet, Grasp the Weapon of Culture. The act made it illegal for anyone in the United States to advocate, abet, or teach the desirability of overthrowing the government. The main objective of the act was to undermine the Communist Party and other left-wing political groups in the United States.

During the previous few years over 200 people had been convicted using this act. This included James Cannon, Harry Bridges, Farrell Dobbs, Elizabeth Gurley Flynn, Eugene Dennis, William Z. Foster, Benjamin Davis, John Gates, Robert G. Thompson, Gus Hall, Benjamin Davis, Henry M. Winston, and Gil Green.

Following a nine-month trial in New York's Foley Square Courthouse, Jerome was convicted and sentenced in 1953 to three years at Lewisburg Penitentiary. While in prison he published the novel, A Lantern for Jeremy.

Victor Jerome died in 1965.

Primary Sources

(1) Paul Buhle and Dave Wagner, Radical Hollywood (2002)

A sometime novelist, Jerome was known first for his marriage to Rose Pastor Stokes, the former shop-girl strike leader and charismatic radical heroine of the 1910s-20s-which gained him ready access to the upper realms of Communist cultural critics-but second for his status as a heresy hunter. He had already, by the time of his first visits to Hollywood, attempted to define the proper forms of proletarian literature, seeking to forbid deviating methods to serious revolutionaries. By 1935 he had taken over the Party's theoretical journal, The Communist, and remained more or less in that post for twenty years. Destined to play a melancholy role in the Hollywood Left, he made intermittent trips to Hollywood from 1936 onward, cadging funds out of successful writers or directors, assuring listeners of the Soviet leadership's rectitude (especially in the face of discouraging events like the Moscow Trials), and issuing directives that could not actually be followed but that kept official leader Lawson on tenterhooks.

(2) Elia Kazan, Elia Kazan: A Life (1989)

Molly Kazan had been an instructor at the Theatre Union and had had experience with politically "correct" amateurs throwing their ideological weight around in an artistic organization. She'd been through the Theatre of Action experience with me. She'd been witness to the spanking the Party had given Jack Lawson and his humiliating retreat from his personal artistic intention. "Crawling to the feet of V. J. Jerome," she'd called it. "What the hell does Jerome know about the operation of a theatre?" she'd asked. Had he ever been backstage? Jack, having regretted his choice of the hero of Gentle Woman and expressed his contrition at length, moved to Hollywood, where, converted and rewarded, he was running the Party's show. Ranks marching left were not to be broken.I carried Comrade Jerome's message back to our regular Tuesday night meeting in Joe Bromberg's dressing room, passed on his instruction that our cell should immediately work to transform the Group into a collective, a theatre run by its actors. It was a surprise to me when the members of our cell quickly and unanimously did what the Theatre of Action people had done in the matter of the La Guardia play - give in to the political directive from the man on Twelfth Street. Then it was my turn to speak. I was timid; despite my present reputation as a bullheaded man, up until that time breaking ranks was an act of boldness for me. I surprised everyone by my recalcitrance; I surprised myself. I believe I sounded apologetic for disagreeing. I could feel bewilderment and impatience around me. I suppose the position I took was a sign of disrespect for my fellow actors' political savvy. And possibly their courage. They voted me down.

Later I found out that they blamed Molly and the influence of Harold Clurman. They saw that I was on the side of the directors, not the "people". Therefore I was undemocratic. And therefore - how ironic! - not a good Communist. But what they blamed most was my character: I was an opportunist who'd do anything to get to the top. I've been accused of this many times by many people. The fact is that I do have - call it elitism - strong feelings that some people are smarter, more educated, more energetic and altogether better qualified to lead than others. I also believed then and believe now that a person's agreeing with me politically is not a guarantee' of his or her artistic talent. I was not impressed with the arguments of my cellmates.

References

(1) Paul Buhle and Dave Wagner, Radical Hollywood (2002) page 84

(2) Eugene Lyons, letter to John Whitcomb (8th January, 1958)

(3) Arthur and Pearl Zipser, Fire and Grace: The Life of Rose Pastor Stokes (1989) page 271

(4) Rose Pastor Stokes, letter to Jeanette Pearl (December, 1926)

(5) Daily Chronicle (21st June, 1933)

(6) Judith Rosenbaum, Rose Pastor Stokes (1995-2015)

(7) Paul Buhle and Dave Wagner, Radical Hollywood (2002) page 85

(8) Patrick McGilligan and Paul Buhle, Tender Comrades (1997) page 145

(9) Victor Navasky, Naming Names (1982) page 78

(10) Paul Buhle and Dave Wagner, Radical Hollywood (2002) page 85

(11) John Bright, quoted in Tender Comrades (1997) page 151

(12) Granville Hicks, testimony before the Un-American Activities Committee (February, 1953)

(13) Elia Kazan, Elia Kazan: A Life (1989) page 144

(14) Budd Schulberg, testimony before the Un-American Activities Committee (23rd May, 1951)

(15) Victor Navasky, Naming Names (1982) page 286

(16) Elizabeth Bentley, FBI interview (8th November, 1945)

(17) Nigel West, Venona: The Greatest Secret of the Cold War (2000) pages 109

(18) Robert J. Lamphere, The FBI-KGB War (1986) page 254

(19) Albert Maltz, New Masses (12th February, 1946)

(20) Victor Navasky, Naming Names (1982) page 288

(21) Howard Fast, New Masses (26th February, 1946)

(22) Joseph North, New Masses (26th February, 1946)

(23) Alvah Bessie, New Masses (12th March, 1946)

(24) Paul Buhle and Dave Wagner, Radical Hollywood (2002) page 264

(25) John Howard Lawson, New Masses (12th March, 1946)

(26) Albert Maltz, New Masses (9th April, 1946)

(27) I. F. Stone, letter to Dashiell Hammett (18th March, 1952)

(28) Howard Fast, Being Red (1990) pages 270-273

(29) Cedric Belfrage & James Aronson, Something to Guard (1978) pages 62-63