On this day on 4th December

On this day in 1760 anti-slavery campaigner Elizabeth Coltman was born in Leicester. Her father, John Coltman, was a successful worsted manufacturer. Her mother, Elizabeth Cartwright (1737–1811), was a published poet and book reviewer. John Wesley visited the family home in 1785.

Elizabeth, known as Bess when young, "was singular in her childhood" and it was said that when she gave her "pennies to a beggar and choosing for rescue a plain kitten in preference to a pretty one". Her talent for landscape painting gave her father "half a mind" to "make her artist" like Angelica Kauffman.

On 10th March 1787 Elizabeth married John Heyrick, a Methodist lawyer. Elizabeth Heyrick was still childless when her husband died of a heart-attack eight years later. According to her biographer: "The marriage was said to have been stormy, but she mourned fervently, with lifelong observance of the anniversary of his death. They had no children."

After the death of her husband Elizabeth Heyrick moved back into her parents home. Elizabeth, now a member of the Society of Friends, renounced all worldly pleasures and devoted herself to social reform. A follower of Tom Paine, she campaigned against bull-baiting and became a prison visitor. Elizabeth also wrote eighteen political pamphlets on a wide variety of subjects including, the Corn Laws. In one pamphlet she pointed out that a women was "especially qualified to plead for the oppressed."

Adam Hochschild has pointed out that Elizabeth Heyrick was a committed political reformer "She (Elizabeth Heyrick) stopped a bull-baiting contest by buying the bull and hiding it in the parlor of a nearby cottage until the angry crowd went away. To experience the life of Irish migrant workers, she lived in a shepherd's cottage eating only potatoes. She visited prisons and paid fines to get poachers released... She called for laws reforming prisons and limiting the workday; she supported a strike by weavers in her hometown of Leicester, even though her own brother was an employer in the industry."

Heyrick's main concern was the campaign against slavery. Her elder brother, Samuel Coltman, had been part of the original abolition movement in the 1790s. It is claimed that Elizabeth was influenced by the ideas of the Unitarian movement. "Many unitarians concluded that the only significant difference between women and men was men's capacity for physical force. There appeared no 'natural' reasons why women should not use their capacities for intellectual and moral growth to bring social progress, including the removal of slavery as an institution that stunted intellectual and moral growth."

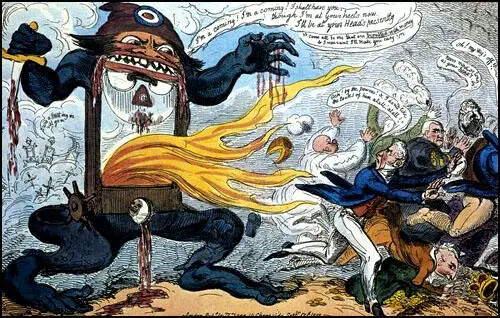

In 1824 Elizabeth Heyrick published her pamphlet Immediate not Gradual Abolition. In her pamphlet Heyrick argued passionately in favour of the immediate emancipation of the slaves in the British colonies. This differed from the official policy of the Anti-Slavery Society that believed in gradual abolition. She called this "the very masterpiece of satanic policy" and called for a boycott of the sugar produced on slave plantations.

In the pamphlet Heyrick attacked the "slow, cautious, accommodating measures" of the leaders. "The perpetuation of slavery in our West India colonies is not an abstract question, to be settled between the government and the planters; it is one in which we are all implicated, we are all guilty of supporting and perpetuating slavery. The West Indian planter and the people of this country stand in the same moral relation to each other as the thief and receiver of stolen goods".

The leadership of the organisation attempted to suppress information about the existence of this pamphlet and William Wilberforce gave out instructions for leaders of the movement not to speak at women's anti-slavery societies. His biographer, William Hague, claims that Wilberforce was unable to adjust to the idea of women becoming involved in politics "occurring as this did nearly a century before women would be given the vote in Britain".

Although women were allowed to be members they were virtually excluded from its leadership. Wilberforce disliked to militancy of the women and wrote to Thomas Babington protesting that "for ladies to meet, to publish, to go from house to house stirring up petitions - these appear to me proceedings unsuited to the female character as delineated in Scripture".

However, George Stephen disagreed with Wilberforce on this issue and claimed that their energy was vital in the success of the movement: "Ladies Associations did everything... They circulated publications; they procured the money to publish; they talked, coaxed and lectured: they got up public meetings and filled our halls and platforms when the day arrived; they carried round petitions and enforced the duty of signing them... In a word they formed the cement of the whole anti-slavery building - without their aid we never should have kept standing."

Thomas Clarkson, another leader of the ant-slavery movement, was much more sympathetic towards women. Unusually for a man of his day, he believed women deserved a full education and a role in public life and admired the way the Quakers allowed women to speak in their meetings. Clarkson told Elizabeth Heyrick's friend, Lucy Townsend, that he objected to the fact that "women are still weighed in a different scale from men... If homage be paid to their beauty, very little is paid to their opinions."

Records show that about ten per cent of the financial supporters of the organisation were women. In some areas, such as Manchester, women made up over a quarter of all subscribers. Lucy Townsend asked Thomas Clarkson how she could contribute in the fight against slavery. He replied that it would be a good idea to establish a women's anti-slavery society. (

Elizabeth Heyrick was an early exponent of direct action and organised a sugar boycott in Leicester. She visited all the city's grocers to urge them to only stock goods that did not involve slavery. She pointed out: "The West Indian planter and the people of this country, stand in the same moral relation to each other, as the thief and the receiver of stolen goods... Why petition Parliament at all, to do that for us, which... we can do more speedily and more effectively for ourselves."

On 8th April, 1825, Lucy Townsend held a meeting at her home to discuss the issue of the role of women in the anti-slavery movement. Townsend, Elizabeth Heyrick, Mary Lloyd, Sarah Wedgwood, Sophia Sturge and the other women at the meeting decided to form the Birmingham Ladies Society for the Relief of Negro Slaves (later the group changed its name to the Female Society for Birmingham). The group "promoted the sugar boycott, targeting shops as well as shoppers, visiting thousands of homes and distributing pamphlets, calling meetings and drawing petitions."

The society which was, from its foundation, independent of both the national Anti-Slavery Society and of the local men's anti-slavery society. As Clare Midgley has pointed out: "It acted as the hub of a developing national network of female anti-slavery societies, rather than as a local auxiliary. It also had important international connections, and publicity on its activities in Benjamin Lundy's abolitionist periodical The Genius of Universal Emancipation influenced the formation of the first female anti-slavery societies in America".

The formation of other independent women's groups soon followed the setting up of the Female Society for Birmingham. This included groups in Nottingham (Ann Taylor Gilbert), Sheffield (Mary Anne Rawson, Mary Roberts), Leicester (Elizabeth Heyrick, Susanna Watts), Glasgow (Jane Smeal), Norwich (Amelia Opie, Anna Gurney), London (Mary Anne Schimmelpenninck, Mary Foster), Darlington (Elizabeth Pease) and Chelmsford (Anne Knight). Eventually there were seventy-three of these women's organisations campaigning against slavery.

Although virtually all the prominent male opponents of slavery were still talking about the freeing of the slaves over a thirty year period, Elizabeth Heyrick, severely criticised these men and demanded a different strategy. In the 1826 General Election she called for people to vote only for candidates who supported the freeing the slaves now. She quoted a letter that she had received from a woman in Wiltshire: "Men may propose only gradually to abolish the worst of crimes... but why should we countenance such enormities? We must not talk of gradually abolishing murder, licentiousness, cruelty, tyranny."

The Anti-Slavery society realised the importance of Elizabeth Heyrick's as a propagandist for the cause. Her writing had the ability to arouse public opinion. In 1828 they printed copies of her pamphlet, Appeal to the Hearts and Consciences of British Women. The main method of distribution was house-to-house canvassing, where publications were sold to the better-off or lent to the poor.

In 1830, the Female Society for Birmingham submitted a resolution to the National Conference of the Anti-Slavery Society calling for the organisation to campaign for an immediate end to slavery in the British colonies. Elizabeth Heyrick, who was treasurer of the organisation suggested a new strategy to persuade the male leadership to change its mind on this issue. In April 1830 they decided that the group would only give their annual £50 donation to the national anti-slavery society only "when they are willing to give up the word 'gradual' in their title." At the national conference the following month, the Anti-Slavery Society agreed to drop the words "gradual abolition" from its title. It also agreed to support Female Society's plan for a new campaign to bring about immediate abolition.

In her final years Elizabeth Heyrick grew very depressed about her lack of success to get slavery abolished. She wrote to Lucy Townsend: "Nothing human can dispel that despairing torpor into which I have been plunging deeper and deeper for many months past." Elizabeth Heyrick died on 18th October 1831 and therefore did not live to see the passing of the 1833 Abolition of Slavery Act.

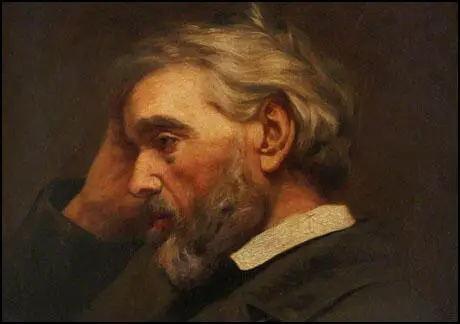

On this day in 1795 Thomas Carlyle, the eldest son of James Carlyle, a stonemason, and Margaret Aitken, the daughter of a bankrupt Dumfriesshire farmer, was born in Ecclefechan in Scotland. His mother gave birth to eight children after Thomas: Alexander (1797–1876), Janet (1799–1801), John Aitken Carlyle (1801–1879), Margaret (1803–1830), James (1805–1890), Mary (1808–1888), Jane (1810–1888), and a second Janet (1813–1897).

Carlyle was brought up as a strict Calvinist and was educated at the village school. According to his biographer, Fred Kaplan: "As a boy he learned reading from his mother, arithmetic from his father; he attended a private school in Ecclefechan and then, at the age of six, the nearby Hoddam parish school. He immediately became the pride of the schoolmaster, the young person on whom approving adults and jealous schoolmates place the burden of differentness. For his parents that quality had its rightful place in the circle of tradition. If their son was to be a man of learning, he would be a minister of the Lord; within their society the alternative was either madness or apostasy." Carlyle later wrote: "A man's religion consists not of the many things he is in doubt of and tries to believe, but of the few he is assured of, and has no need of effort for believing".

In 1806 he entered Annan Academy, a school that specialized in training large classes, at low cost, for university entrance at the age of fourteen. At this time his best subject was mathematics but he also excelled in foreign languages. He received training in French and Latin but over the next few years taught himself Spanish, Italian, and German. Carlyle also took a keen interest in literature and read the work of Daniel Defoe, Henry Fielding, Tobias Smollett, Laurence Sterne and William Congreve. He told Henry Fielding Dickens that he was a "gawky youth with a shock of red hair, and explained how he used to be bullied by other boys."

Carlyle was an excellent student and he won his place at the University of Edinburgh. In November 1809 he walked the 80 mile journey to Edinburgh. It took him three days and he later commented that by the beginning of the second day he had travelled further from Ecclefechan than his father was ever to do in his life. Carlyle was very unhappy in first year at university. His religious upbringing made it impossible for "him to participate" in the "amusements, too often riotous and libertine" of the other students.

Carlyle's father expected him to attend divinity school after completing his university studies. However, he rejected this idea and in 1814 became a mathematics teacher at Annan Academy at £70 per annum. In 1816 he obtained a teaching position at Kirkcaldy where he taught Latin, French, arithmetic, bookkeeping, geometry, navigation and geography. In November 1818, suffering from depression, Carlyle resigned and returned to Edinburgh.

In late May 1821 met the recently widowed Grace Welsh (1782–1842) and her nineteen-year-old daughter Jane Baillie Welsh. Carlyle was immediately impressed with Jane and described her as a "tall aquiline figure, of elegant carriage and air". According to Fred Kaplan, the author of Thomas Carlyle: A Biography (1983): "Carlyle spoke that evening of his own reading, writing, and literary ambitions. Jane listened intently, impressed by his learning and amused by his Annandale accent and country awkwardness.... Frightened of marriage because, among other reasons, she was frightened of sex, Jane Welsh could not imagine that such a man could become her husband." However, she was willing to read the articles he was writing and came to the conclusion that he was a "genius".

Although he disliked teaching, Carlyle agreed to tutor the two sons of Isabella and Charles Buller, on the rather generous sum of £200 per annum, about twice as much as his father had ever earned as a stonemason. In the spring of 1823 Carlyle was commissioned to write a short biographical sketch of Friedrich Schiller for The London Magazine. He was also an expert on Johann Wolfgang von Goethe and in 1824 he completed a translation of Wilhelm Meister's Apprenticeship. Later that year he moved to London where he associated with Charles Lamb, Samuel Taylor Coleridge, and Henry Crabb Robinson.

After much prevarication Jane Welsh agreed to marry Thomas Carlyle. The wedding took place on 17th October 1826. Fred Kaplan has argued: "Clearly, puritanical inhibitions and romantic idealizations were in the 7 foot-wide bed with two sexual innocents. Fragile evidence suggests that though they were able to express affection with whispers and embraces their sexual relationship did not provide physical satisfaction to either of them, despite their efforts during the first half-dozen or so years of the marriage." Carlyle's biographer James Anthony Froude has argued that the marriage was unconsummated.

The couple settled in Craigenputtock. He told his friend, Thomas Story Spedding: "It is one of the most unoccupied, loneliest, far from one of the joyfullest of men. From time to time I feel it absolutely necessary to get into entire solitude; to beg all the world, with passion if they will not grant it otherwise, to be so kind as to leave me altogether alone. One needs to unravel and bring into some articulation the villainous chaos that gathers round heart and head in that loud-roaring Babel; to repent of one's many sins, to be right miserable, humiliated, and do penance for them - with hope of absolution, of new activity and better obedience!"

Carlyle appeared to hold his wife in great esteem. He later wrote: "She could do anything well to which she chose to give herself.... She had a keen clear incisive faculty of seeing through things, and hating all that was make-believe or pretentious. She had good sense that amounted to genius. She loved to learn and she cultivated all her faculties to the utmost of her power. She was always witty … in a word she was fascinating and everybody fell in love with her."

Thomas Carlyle's reputation as an expert on literature and philosophy resulted in him receiving commissions from The Edinburgh Review and The Foreign Review. He also started work on his first book, Sartor Resartus. However, he had great difficulty finding someone willing to publish this philosophical work. It eventually was serialized in Fraser's Magazine (1833-34).

Thomas and Jane Carlyle moved to London. He developed a close friendship with John Stuart Mill and he had several articles published in his Westminster Review. Mill was very close to Harriet Taylor, who was married to Henry Taylor. In 1833 Harriet negotiated a trial separation from her husband. She then spent six weeks with Mill in Paris. On their return Harriet moved to a house at Walton-on-Thames where John Stuart Mill visited her at weekends. Although Harriet Taylor and Mill claimed they were not having a sexual relationship, their behaviour scandalized their friends. As a result, the couple became socially isolated. However, Carlyle stood by Mill.

It was Mill who suggested that Carlyle should write a book about the French Revolution. He agreed and started the book in September 1834. After completing the first volume he sent it to Mill for his comments. On the night of 6th March 1835, Mill arrived at Carlyle's house with the news that the manuscript had been burnt by mistake at the home of Harriet Taylor. The following day he decided to rewrite volume one again. The three volume book was not finished until 12th January, 1837. Ralph Waldo Emerson arranged for it to be published in America.

John Stuart Mill was active in the campaign for parliamentary reform, and was one of the first to suggest that women should have the same political rights as men. He introduced Carlyle to other political radicals such as Frederick Denison Maurice, Harriet Martineau, James Leigh Hunt, Robert Southey and William Wordsworth.

Mill urged Carlyle to write a pamphlet about parliamentary reform. In March 1838 he wrote: "Unluckily or luckily this notion of writing on the Working Classes has in the interim died away in me; and I have altogether lost it for the present. I have got upon Thuycidides, Johannes Müller, the Crusades, and a whole course of objects connected with my Lectures; sufficient to occupy me abundantly till that fatal time come. We will commit my Discourse on the Working Classes once more to the chapter of chances. I do not know that my train of argument would have specially led me to insist on the question you allude to: but if it had - ! In fact it were a right cheerful thing for me could I get to see that general improvement were going on there; and I think I should in that case wash my hands of Radicalism forever and a day." Carlyle was disturbed by the fact that working-class leaders such as Francis Place disagreed with his approach to the subject. Carlyle wrote: "Francis Place is against me, a man entitled to be heard."

Thomas Carlyle was opposed to Physical Force Chartism. In 1839 he wrote to his friend, Thomas Story Spedding: "What you say of Chartism is the very truth: revenge begotten of ignorance and hunger! We have enough of it here too; the material of it exists I believe in the hearts of all our working population, and would right gladly body itself in any promising shape; but Chartism begins to seem unpromising. What to do with it? Yes, there is the question. Europe has been struggling to give some answer, very audibly since the year 1789! The gallows and the bayonet will do what they can; these altogether failing, we may hope a quite other sort of exorcism will be tried.... Unless gentry, clergy and all manner of washed articulate-speaking men will learn that their position towards the unwashed is contrary to the Law of God, and change it soon, the Law of Man, one has reason to discern, will change it before long, and that in no soft manner.... The fever-fit of Chartism will pass, and other fever-fits; but the thing it means will not pass, till whatsoever of truth and justice lies in the heart of it has been fulfilled; it cannot pass till then, a long date, I fear."

Carlyle met Charles Dickens for the first time in 1840. Carlyle described Dickens as "a fine little fellow... a face of most extreme mobility, which he shuttles about - eyebrows, eyes, mouth and all - in a very singular manner while speaking... a quiet, shrewd-looking, little fellow, who seems to guess pretty well what he is and what others are." The two men became close friends. Dickens told one of his sons that Carlyle was the man "who had influenced him most" and his sister-in-law, that "there was no one for whom he had a higher reverence and admiration".

Carlyle published Chartism in 1841. He argued the immediate answers to poverty and overpopulation was improved education and an expansion of emigration. This position angered many of his radical friends. Other books by Carlyle during this period included On Heroes, Hero Worship and the Heroic in History (1841) and Past and Present (1843).

Carlyle highly disapproved of the industrial revolution. Something he called the "Mechanical Age". In 1842 he described his first journey on a steam locomotive: "I was dreadfully frightened before the train started; in the nervous state I was in, it seemed to me certain that I should faint, from the impossibility of getting the horrid thing stopped."

The literary critic, Richard Hengist Horne, was one of the first people to champion the writing of Carlyle. He argued in A New Spirit of the Age (1844): "Mr. Carlyle... has knocked out his window from the blind wall of his century... We may say, too, that it is a window to the east; and that some men complain of a certain bleakness in the wind which enters in at it; when they should rather congratulate themselves with him on the aspect of the new sun beheld through it, the orient of hope of which he has discovered to their eyes." James Fitzjames Stephen was another supporter of Carlyle: "Regarded as works of art, we should put the best of Mr. Carlyle's writings at the very head of contemporary literature… If he is the most indignant and least cheerful of living writers, he is also one of the wittiest and the most humane." Peter Ackroyd has argued that "there is a strong case to be made for Carlyle being the single most important writer in England during the 1840s"

Andrew Sanders has argued: "What the early Victorians most admired in Carlyle was his ability to disturb them. It was he who seemed to have identified the nature of their restlessness and who had put his finger on the racing pulse of the age.... Carlyle was, and remains, an uncomfortable and disconcerting writer: edgy, prickly, experimental, challenging. He seems, by turns, to be persuasively sophisticated and provocatively direct. He was an outsider to mainstream early Victorian culture in two ways: he had been born in the same year as John Keats and was approaching 40 when he moved to London; he was also, by origin, a poor Scot who had been educated at the University in Edinburgh which still basked in the afterglow of the Scottish Enlightenment."

Carlyle was always concerned about his health but it was Jane who was constantly unwell. She wrote to a friend that she was "suffering from a bad nervous system, keeping me in a state of greater or less physical suffering". Thomas Carlyle, wrote to Catherine Dickens on 24th April, 1843: "We are such a pair of poor sickly creatures here, we have to deny ourselves the pleasure of dining out anywhere at present; and, I may well say with very great reluctance, even that of dining at your house on Saturday, one of the agreeablest dinners that human ingenuity could propose for us!"

Carlyle became a friend of Giuseppe Mazzini, the Italian revolutionary, and they had long discussions on parliamentary reform. Jane Carlyle and Mazzini developed an increasing intimate relationship. In 1846 Jane considered leaving her husband over his platonic relationship with Lady Harriet Baring, the wife of Bingham Baring, 2nd Baron Ashburton, but Mazzini strongly advised her not to.

After the Revolutions of 1848, Carlyle developed reactionary views. In 1850 he wrote a series of twelve pamphlets to be published in monthly installments over the next year. In Latter-Day Pamphlets he attacked democracy as an absurd social ideal and commented that it was absurd that "truth could be discovered by totting up votes". However, at the same time Carlyle criticized hereditary aristocratic leadership as "deadening". Carlyle suggested that people should be ruled by "those most able". Although Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels agreed with Carlyle about aristocratic leadership, they completely rejected his ideas on democracy.

In 1854 Charles Dickens dedicated his book, Hard Times to Carlyle. He also helped Dickens with his book, A Tale of Two Cities (1859). Peter Ackroyd, the author of Dickens (1990), has pointed out: "He (Dickens) had always admired Carlyle's History of the French Revolution, and asked him to recommend suitable books from which he could research the period; in reply Carlyle sent him a cartload of volumes from the London Library. Apparently Dickens read, or at least looked through, them all; it was his aim during the period of composition only to read books of the period itself."

On 21st April 1866, Jane Carlyle went for her regular afternoon carriage ride in Hyde Park. Thomas Carlyle's biographer, Fred Kaplan, argues that "after several circuits of the park the driver, alarmed by Mrs Carlyle's lack of response to his request for further instructions, asked a woman to look into the carriage." According to the witness she "was leaning back in one corner of the carriage, rugs spread over her knees; her eyes were closed, and her upper lip slightly, slightly opened".

Henry Fielding Dickens visited him during this period: "It was my privilege to pay him two or three visits at his house in Cheyne Row after my father's death. I went there for the first time with feelings of awe and some trepidation. This was but natural in the case of a very young man paying a visit to an old man of Carlyle's rare gifts and immense reputation, and one who could be very dour at times. But I found that such feeling was quite uncalled for and he at once put me entirely at my ease. He was gifted with a high sense of humour, and when he laughed he did so heartily, throwing his head back and letting himself go."

Carlyle's early articles inspired social reformers such as John Ruskin, Charles Dickens, John Burns, Tom Mann and William Morris. However, in later life he turned against all political reform and argued against the 1867 Reform Act. He also expressed his admiration for strong leaders. This is illustrated by his six volume History of Frederick the Great (1858-1865) and The Early Kings of Norway (1875). In the last few years of his life, Carlyle's writing was confined to letters to The Times. Thomas Carlyle died at his home at 5 Cheyne Row, Chelsea, on 5th February, 1881.

On this day in 1822 educationalist Frances Power Cobbe was born in Dublin. Frances Power Cobbe, the fifth child and only daughter of Charles Cobbe (1781–1857), an Anglo-Irish landowner, and his wife, Frances Conway (1777–1847), was born in Dublin on 4th December 1822. Cobbe was educated at home, except for two years at a school in Brighton. According to her biographer, Barbara Caine: "Cobbe regarded her schooling, which cost £1000, as an interruption to her education and a complete waste of time. The noise, frivolity, pointless routine, and complete lack of intellectual stimulation contrasted strongly with her pleasurable life at home, spent in close contact with her accomplished and beloved mother."

In 1838 Cobbe was recalled from school when her mother's ill health made it necessary for her to take over the housekeeping. She continued to study and her loss of faith caused considerable distress to her mother, who died in 1847. When she confessed some of her religious doubts to her father she was banished from the house to live with her brother. After several months she was allowed home to act as housekeeper. Cobbe further upset her father by publishing Essay on the Theory of Intuitive Morals (1855).

Cobbe's was left a small legacy when her father died in 1857. The following year she moved to Bristol, where she lived with Mary Carpenter, the Unitarian social reformer and philanthropist, assisting her with her ragged schools and reformatory work. Barbara Caine has pointed out: "This arrangement lasted only a few months. Cobbe desired a more intimate form of friendship than Carpenter was able to offer - and Carpenter's complete lack of interest in creature comforts was intolerable to Cobbe."

She now moved to London where she earned her living by writing for newspapers and journals. In 1861 her articles on the subject of women's rights brought her into contact with leading feminists such as Barbara Bodichon and Lydia Becker. She also became friendly with John Stuart Mill who encouraged her in her writing. Cobbe also became a member of the Married Women's Property Committee. 1867 she joined the London Society for Women's Suffrage.

Frances Power Cobbe published several articles on the legal rights of women in marriage. A pamphlet, Wife Torture, which proposed that wife assault should be made grounds for a legal separation, and this influenced the 1878 Matrimonial Causes Act which gave a wife the right to a separation with maintenance, and with custody of any child under ten years of age.

Olive Banks argued: "Her (Frances Power Cobbe) feminism was in many respects aggressive in its attitude to men. In another of her pamphlets, Criminals, Idiots, Women and Minors published in 1869, she argued that men made women economically dependent so that their authority would go unchallenged. Moreover, it was women's economic dependence which made it possible for men to go on ill-treating their wives.... At the same time some of her views were decidedly conservative. In a later pamphlet, The Duties of Women (1881), she stressed that once a woman was a wife and mother these duties were of paramount importance and other interests must be subordinate. She was also firmly conventional in her attitude to sexual morality and in the same pamphlet, condemned the loose living indulged in by advanced women."

Cobbe was also involved in the campaign against vivisection. In 1870 she advocated strengthening the law on experiments on animals, and over the next few years became one of the leaders of the British anti-vivesection movement. It has been argued that there may have "been an identification on her part between man's brutality to animals and his brutality to women."

In 1884 a legacy enabled Cobbe to retire to Wales with Mary Lloyd, a woman she had lived with since 1860. As her biographer has pointed out: "At no time in her life does she seem to have felt any attraction to a man and according to her own account, no man was ever attracted by her." In 1891 she inherited a quite considerable sum as the residuary legatee of the widow of Richard Vaughan Yates, a devoted anti-vivisectionist.

Frances Power Cobbe, who published her autobiography, The Life of Francis Power Cobbe by Herself (1894) died at Hengwrt on 5 April 1904. She was buried in Llanelltyd churchyard, alongside her beloved Mary Lloyd who had died in 1896.

On the day in 1828 Robert Jenkinson, Lord Liverpool one of our worst prime ministers in history died. Jenkinson, the eldest son of the first Earl of Liverpool, was born on 7th June, 1770. He was educated at Charterhouse and Christ Church, Cambridge. At the age of twenty Robert was granted the seat of Appleby, a pocket borough owned by Sir James Lowther. Robert Jenkinson was a Tory and in May 1793, he spoke against Earl Grey's attempt to introduce parliamentary reform.

In February 1801, the Prime Minister, Viscount Sidmouth, promoted Jenkinson to the cabinet. Two years later Sidmouth granted Jenkinson the title Lord Hawkesbury in November 1803. When William Pitt replaced Sidmouth as Prime Minister in 1804, Jenkinson became leader of the government in the House of Lords.

On the death of his father in December, 1808, Jenkinson became the second Earl of Liverpool. When Spencer Perceval became prime minister in 1809 he appointed Lord Liverpool as secretary of war and the colonies. Perceval was assassinated in 1812, by a deranged bankrupt who blamed the government for his troubles, and Lord Liverpool was asked to become Britain's new prime minister.

Lord Liverpool was to remain in office for fifteen years. At first Liverpool was a popular prime minister. In 1815 British forces were victorious at the Battle of Waterloo. The abdication of Napoleon and the successful conclusion of the French Wars improved the public standing of Lord Liverpool's government. It was hoped that with the end of the conflict in Europe Lord Liverpool's government would be able to concentrate on introducing the social reforms that were much needed in Britain.

Lord Liverpool disagreed with those who advocated reform. He reacted to the growth in the radical press by increasing the tax on newspapers. Radical journalists such as Robert Carlile and Henry Hetherington, responded by campaigning for an end to all taxes on knowledge.

In 1817 Britain endured an economic recession. Unemployment, a bad harvest and high prices produced riots, demonstrations and a growth in the Hampden Club movement. Lord Liverpool's government reacted by suspending Habeas Corpus for two years.

The economic situation gradually improved and Liverpool hoped that a reduction in taxation would prevent a revival of radicalism when the suspension of Habeas Corpus came to an end in 1818. This was not the case, and the summer of 1819 saw a series of large gatherings in favour of parliamentary reform, culminating in the massive public meeting at Manchester on 16th August 1819.

Lord Liverpool made it clear that he fully supported the action of the magistrates and the Manchester and Salford Yeomanry. Radicals reacted by calling what happened in St. Peter's Fields, the Peterloo Massacre, therefore highlighting the fact that Liverpool's government was now willing to use the same tactics against the British people that it had used against Napoleon and the French Army.

Liverpool's government decided to take action to prevent further large meetings demanding social reform. In November 1819 Parliament was assembled and it quickly passed the Six Acts. In 1822 Liverpool used similar methods to deal with the distress and disaffection in Ireland.

Liverpool found the heavy burden of running a divided country increasingly stressful. Liverpool began to suffer health problems and on 17th February, 1827, he had a stroke. Liverpool was forced to resign and although he lived for nearly two more years, he was rarely conscious. Lord Liverpool died on 4th December, 1828.

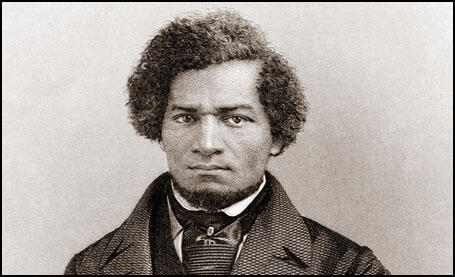

On the day in 1863 Frederick Douglass gives a speech at the Anti-Slavery Society in Philadelphia. Douglass argued: "I am one of those who believe that it is the mission of this war to free every slave in the United States. I am one of those who believe that we should consent to no peace which shall not be an Abolition peace. I am, moreover, one of those who believe that the work of the American Anti-Slavery Society will not have been completed until the black man of the South, and the black men of the North, shall have been admitted, fully and completely, into the body politic of America. I look upon slavery as going the way of all the earth. It is the mission of the war to put it down. I know it will be said that I ask you to make the black man a voter in the South. It is said that the coloured man is ignorant, and therefore he shall not vote. In saying this, you lay down a rule for the black man that you apply to no other class of your citizens. If he knows enough to be hanged, he knows enough to vote. If he knows an honest man from a thief, he knows much more than some of our white voters. If he knows enough to take up arms in defence of this Government and bare his breast to the storm of rebel artillery, he knows enough to vote. All I ask, however, in regard to the blacks, is that whatever rule you adopt, whether of intelligence or wealth, as the condition of voting for whites, you shall apply it equally to the black man. Do that, and I am satisfied, and eternal justice is satisfied; liberty, fraternity, equality, are satisfied, and the country will move on harmoniously."

Frederick Douglass, the son of a white man and a black slave, was born in Tukahoe, Maryland, on 7th February, 1817. He never knew his father and was separated from his mother when very young. Douglas lived with his grandmother on a plantation until the age of eight, when he was sent to Hugh Auld in Baltimore. The wife of Auld defied state law by teaching him to read.

When Auld died in 1833 Frederick was returned to his Maryland plantation. In 1838 he escaped to New York City. He later moved to New Bedford, Massachusetts, where he worked as a labourer. After hearing him make a speech at a meeting in 1841, William Lloyd Garrison arranged for Douglass to become an agent and lecturer for the American Anti-Slavery Society. Douglass was a great success in this work and in 1845 the society helped him publish his autobiography, the Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass.

After the publication of his book, Douglass was afraid he might be recaptured by his former owner and so he travelled to Britain where he lectured on slavery. While in Britain he raised the funds needed to establish his own anti-slavery newspaper, the North Star. This created a break with William Lloyd Garrison, who was opposed to a separate, black-owned press.

During the Civil War Douglass, a Radical Republican, tried to persuade President Abraham Lincoln that former slaves should be allowed to join the Union Army. After the war Douglass campaigned for full civil rights for former slaves and was a strong supporter of women's suffrage.

Douglass held several public posts including assistant secretary of the Santo Domingo Commission (1871), marshall of the District of Columbia (1877-1881) and U.S. minister to Haiti (1889-1891). In 1881 he published the Life and Times of Frederick Douglass. Frederick Douglass died in Washington on 20th February, 1895.

On this day in 1864 political activist Selina Coombe was born in Callington. Selina's father was a navvy and was away working on a construction job when he died of typhoid fever. Jane, her two youngest children and her seventy-four year old mother were all left destitute by Charles Cooper's death. There was little work in Cornwall so Jane decided to follow the example of two eldest sons, Richard and Charles, and seek work in the textile mills of northern England.

Jane Coombe, and her two youngest children, Selina and Alfred, settled in Barnoldswick in 1876. Selina and Alfred soon found work in the local textile mill. Selina, who was now twelve years old, spent half the day in the factory and the other half at school. She was employed as a "creeler" and it was her responsibility to make sure there was a constant supply of fresh bobbins for the cotton emerging from the card frames. When Selina reached the age of thirteen she was able to leave school and work full-time in the Barnoldswick Mill. Selina received eight shillings for a fifty-six hour week, and this enabled the family to move out of temporary accommodation and rent a small house close to the mill.

Jane's rheumatism continued to get worse and soon after arriving in Barnoldswick she was restricted to staying at home. Jane Coombe carried on taking in work as a dressmaker but by 1882 her rheumatism became so bad that she could no longer walk. Selina now had to leave Barnoldswick to look after her bed-ridden mother. Luckily, Jane retained the use of her hands and so with a small sewing machined fixed to a board, she still able to make the clothes that were so highly valued in the neighbourhood. To raise extra money Selina took in washing.

When Jane Coombe died in 1889, Selina was able to return to work in the factory. Selina joined the Nelson branch of the Cotton Worker's Union. Although the vast majority of members were women, the union was run by men. Selina thought that was unfair as it influenced the issues that the union became involved in. Selina for example, objected to the system of providing toilets without doors. In 1891 Selina became involved in a trade union dispute where attempts were made to force employers to provide decent toilet facilities. Selina also objected to the way that male overlookers treated young women workers in factory. However, the male leadership of the union showed little interest in these complaints about sexual harassment.

As well as her union activities, Selina also began attending education classes organised by the Women's C0operative Guild in Nelson. By 1889 the General Secretary of the Guild was Margaret Llewelyn Davies, who had recently completed her university studies at Girton College, that had been founded by her aunt, Emily Davies, in 1869.

One of the main objectives of the Women's Cooperative Guild was to encourage women to "discuss matters beyond the narrow confines of their domestic lives." Selina also began reading books about history and was gradually building up her knowledge of politics. She also starting buying medical books so that she would be able to advise fellow workers who were unable to afford a visit to the doctors. Her collection included The Law of Population, a book written by Annie Besant on birth-control.

In 1892 the Independent Labour Party (ILP) was formed in Nelson. Selina was attracted to the party's claims that it supported equal rights for women. It was at the local ILP that Selina met Robert Cooper, a local weaver who was a committed socialist and an advocate of women's suffrage. Cooper had previously worked for the Post Office but had been sacked for his trade union activities.

Selina married Robert Cooper in 1896 and despite giving birth to a couple of children in the first three years of marriage, she continued her involvement in politics. Selina's first child, John Ruskin Cooper,who was named after the writer, John Ruskin, who had most influenced her political ideas, died of bronchitis when he was four months old.

In 1900 Selina Cooper joined the North of England Society for Women's Suffrage. Other members at the time included Esther Roper, Eva Gore-Booth, Emmeline Pankhurst and Christabel Pankhurst. Cooper wrote at the time: "(a) That in the opinion of your petitioners the continued denial of the franchise to women is unjust and inexpedient. (b) In the home, their position is lowered by such an exclusion from the responsibilities of national life. (c) In the factory, their unrepresented condition places the regulation of their work in the hands of men who are often their rivals as well as their fellow workers."

Selina helped organize a petition that was signed by women working in the Lancashire cotton mills. Selina alone collected the signatures of 800 women from local textile factories. By spring 1901, 29,359 women from Lancashire had signed the petition in favour of women's suffrage and Selina was chosen as one of the delegates to present the petition to the House of Commons.

In 1901 the Independent Labour Party asked Selina to stand as a candidate for the forthcoming Poor Law Guardian elections. Although women had been allowed to stand as candidates since the passing of the Municipal Franchise Act in 1869, no working-class woman had ever been elected to one of these bodies. Although the local newspapers campaigned against Selina Cooper, she was elected.

Selina was outvoted on most issues but she did persuade the Board of Guardians to allow elderly people in the workhouse more freedom of movement. Although her duties as a Guardian took up a lot of her time, Selina continued to campaign for women's suffrage. At the National Conference of the Labour Party in 1905, Selina made a speech where she urged the leadership to fully support women's suffrage. The following year she helped form the Nelson and District Suffrage Society.

Selina developed a national reputation for her passionate speeches in favour of women's rights. Millicent Fawcett was a great admirer of Selina Cooper and she was often asked to speak at NUWSS rallies. In 1910 she was chosen to be one of the four women to present the case for women's suffrage to Herbert Asquith, the British Prime Minister.

In 1911 Selina Cooper and Ada Nield Chew became organizers for the NUWSS. According to Elizabeth Crawford, the author of The Suffragette Movement (1999): "She spent the next years travelling around the country; in 1908, for instance, she took part in at least eight by-elections. When she was away from home the NUWSS paid the expense of a housekeeper to care for her daughter, who had been born in 1900."

Cooper influenced the NUWSS decision in April 1912 to support Labour Party candidates in parliamentary by-elections. Emily Davies, a member of the Conservative Party, and Margery Corbett-Ashby, an active supporter of the Liberal Party, resigned from the NUWSS over this decision. However, others like Catherine Osler, resigned from the Women's Liberal Federation in protest against the government's attitude to the suffrage question.

The NUWSS established an Election Fighting Fund (EFF) to support these Labour candidates. The EFF Committee, which administered the fund, included Margaret Ashton, Henry N. Brailsford, Kathleen Courtney, Muriel de la Warr, Millicent Fawcett, Catherine Marshall, Isabella Ford, Laurence Housman, Margory Lees and Ethel Annakin Snowden.

In August 1913 Selina Cooper wrote in The Common Cause: "One reason why I am a convinced suffragist is that the mothers (even as wage earners) take the greater share of the responsibility in the upbringing of their children; therefore, they ought to have the greater means, not the less, to enable them to do justice to the rising generation."

During the First World War Selina worked on several committees organizing relief work in Nelson. This included Nelson's first ever Maternity Centre. Selina took great pleasure in the fact that she personally helped to deliver fifteen babies during this period.

Although willing to help people suffering from the consequences of the war, Selina, who was a pacifist, refused to take part in army recruiting campaigns. Selina was totally opposed to military conscription and after its introduction in 1916, became involved in helping those men who were sent to prison for refusing to fight. In 1917 Selina persuaded over a thousand women in Nelson to take part in a Women's Peace Crusade procession. The meeting ended in a riot and mounted police had to be called in to protect Selina Cooper and Margaret Bondfield, the two main speakers at the meeting.

After the passing of the Qualification of Women Act in 1918 the NUWSS tried to persuade the Labour Party in Nelson to choose Selina Cooper as their candidate in the forthcoming 1918 General Election. However, the Labour Party was very much a male-dominated organisation and no women were selected to fight winnable seats.

Cooper continued to be involved in local politics. She was elected to the town council and became a local magistrate. In the 1930s she played a prominent role in the campaign against fascism. Selina Cooper died at home on 11th November 1946 shortly before her eighty-second birthday.

On this day in 1909 Dora Marsden was arrested for attempting to disrupt a meeting in Southport that was being addressed by Winston Churchill. According to the local newspaper "the security for the meeting was unprecedented in the history of the town". While Churchill was speaking he was interrupted by Marsden. Emmeline Pankhurst later recalled that Marsden was "peering through one of the great porthole openings in the slope of the ceiling, was seen a strange elfin form with wan, childish face, broad brow and big grey eyes, looking like nothing real or earthly but a dream waif."

Dora Marsden provided an account of what happened next in Votes for Women: "A dirty hand was was thrust over my mouth, and a struggle began. Finally I was dropped over a ledge, pushed through the broken window, and we began to roll down the steep sloping roof side. Two stewards, crawling up from the other side, shouted out to the two men who had hold of me." Despite being arrested the local magistrate dismissed all charges against them.

On this day in 1939 Ada Wright died.

Ada Cecile Granville Wright, the daughter of James Wright (1826-1896) and Sarah Jane Massey (1826-1907), was born in Manche, Normandy, in northwestern France, on 9th February 1861. Wright attended the Slade School of Fine Art and University College London, where she was taught English Literature by the socialist activist, Edward Aveling, the partner of Eleanor Marx, the daughter of Karl Marx.

Wright wanted to became a social worker, but at the time was prevented in doing so by her father. Although she accepted her father's instructions she became interested in the subject of women's rights and commented that she "wished I had been born a boy." Wright was described as "one of those quiet women whose gentle and calm manner hides a courageous and indomitable nature of unexpected depths."

The family moved to Sidmouth and in 1885 her father eventually agreed for her to to join the local settlement house. During this period she helped young people from the local workhouse to find "suitable employment". (4) She also joined the National Union of Suffrage Societies. Later she moved to London and run a club for working-class girls in Soho. She also had a spell as a probationer nurse at the London Hospital.

Ada's father, James Wright, died in 1896, leaving £40,944 to his family. By 1901, Ada Wright was residing with her widowed mother and her three unmarried sisters (Agnes, Florence & Blanche) at "Rushmore", Branksome Road, Bournemouth.

In October 1903 Emmeline Pankhurst decided to establish the Women's Social and Political Union (WSPU). Emmeline stated that the main aim of the organisation was to recruit women into the struggle for the vote. "We resolved to limit our membership exclusively to women, to keep ourselves absolutely free from any party affiliation, and to be satisfied with nothing but action on our question. Deeds, not words, was to be our permanent motto."

The main objective was to gain, not universal suffrage, the vote for all women and men over a certain age, but votes for women, “on the same basis as men.” This meant winning the vote not for all women but for only the small stratum of women who could meet the property qualification. As one critic suggested, it was "not votes for women", but “votes for ladies.” As an early member of the WSPU, Dora Montefiore, pointed out: "The work of the Women’s Social and Political Union was begun by Mrs. Pankhurst in Manchester, and by a group of women in London who had revolted against the inertia and conventionalism which seemed to have fastened upon... the NUWSS."

Ada Wright, who frustrated by the lack of progress made by the National Union of Suffrage Societies who now considered the organisation as being "ineffective for making the question of justice to women a living force." Ada decided to join and devote all her time the WSPU and volunteered for "pavement chalking, unpaid clerical work at Clement's Inn and campaigning at by-elections."

Wright was arrested for the first time in 1907. In October 1908 she was arrested for obstructing the police at the House of Commons. On 29th June, 1909, Ada Wright and Sarah Carwin were arrested for breaking government windows. They were sentenced to a month in prison. While in Holloway they broke every window in their cells as a protest. Both women were released after being on hunger strike for six days.

In January 1910, H. H. Asquith called a general election in order to obtain a new mandate. However, the Liberals lost votes and was forced to rely on the support of the 42 Labour Party MPs to govern. Henry Brailsford, a member of the Men's League For Women's Suffrage wrote to Millicent Fawcett, the leader of the National Union of Woman's Suffrage Societies (NUWSS), suggesting that he should attempt to establish a Conciliation Committee for Women's Suffrage. "My idea is that it should undertake the necessary diplomatic work of promoting an early settlement".

Emmeline Pankhurst, the leader of the Women's Social and Political Union (WSPU) agreed to the idea and they declared a truce in which all militant activities would cease until the fate of the Conciliation Bill was clear. A Conciliation Committee, composed of 36 MPs (25 Liberals, 17 Conservatives, 6 Labour and 6 Irish Nationalists) all in favour of some sort of women's enfranchisement, was formed and drafted a Bill which would have enfranchised only a million women but which would, they hoped, gain the support of all but the most dedicated anti-suffragists. Fawcett wrote that "personally many suffragists would prefer a less restricted measure, but the immense importance and gain to our movement is getting the most effective of all the existing franchises thrown upon to woman cannot be exaggerated."

The Conciliation Bill was designed to conciliate the suffragist movement by giving a limited number of women the vote, according to their property holdings and marital status. After a two-day debate in July 1910, the Conciliation Bill was carried by 109 votes and it was agreed to send it away to be amended by a House of Commons committee. However, when Keir Hardie, the leader of the Labour Party, requested two hours to discuss the Conciliation Bill, H. H. Asquith made it clear that he intended to shelve it.

Emmeline Pankhurst was furious at what she saw as Asquith's betrayal and on 18th November, 1910, arranged to lead 300 women from a pre-arranged meeting at the Caxton Hall to the House of Commons. Pankhurst and a small group of WSPU members, were allowed into the building but Asquith refused to see them. Women, in "detachments of twelve" marched forward but were attacked by the police.

Votes for Women reported that 159 women and three men were arrested during this demonstration. (19) This included Ada Wright, Catherine Marshall, Eveline Haverfield, Anne Cobden Sanderson, Mary Leigh, Vera Holme, Louisa Garrett Anderson, Kitty Marion, Gladys Evans, Cecilia Wolseley Haig, Maud Arncliffe Sennett, Clara Giveen, Eileen Casey, Patricia Woodcock, Vera Wentworth, Mary Clarke, Henria Williams, Lilian Dove-Wilcox, Minnie Turner, Lucy Burns and Grace Roe.

Sylvia Pankhurst later described what happened on what became known as Black Friday: "As, one after the other, small deputations of twelve women appeared in sight they were set upon by the police and hurled aside. Mrs Cobden Sanderson, who had been in the first deputation, was rudely seized and pressed against the wall by the police, who held her there by both arms for a considerable time, sneering and jeering at her meanwhile.... Just as this had been done, I saw Miss Ada Wright close to the entrance. Several police seized her, lifted her from the ground and flung her back into the crowd. A moment afterwards she appeared again, and I saw her running as fast as she could towards the House of Commons. A policeman struck her with all his force and she fell to the ground. For a moment there was a group of struggling men round the place where she lay, then she rose up, only to be flung down again immediately. Then a tall, grey-headed man with a silk hat was seen fighting to protect her; but three or four police seized hold of him and bundled him away. Then again, I saw Miss Ada Wright's tall, grey-clad figure, but over and over again she was flung to the ground, how often I cannot say. It was a painful and degrading sight. At last, she was lying against the wall of the House of Lords, close to the Strangers' Entrance, and a number of women, with pale and distressed faces were kneeling down round her. She was in a state of collapse."

Several women reported that the police dragged women down the side streets. "We knew this always meant greater ill-usage.... The police snatched the flags, tore them to shreds, and smashed the sticks, struck the women with fists and knees, knocked them down, some even kicked them, then dragged them up, carried them a few paces and flung them into the crowd of sightseers." It was claimed that two women, Cecilia Wolseley Haig and Henria Williams, died because of the beatings they endured that day. "I saw Celilia Haig go out with the rest; a tall, strongly built, reserved woman, comfortably situated, who in ordinary circumstances might have gone through life without receiving an insult, much less a blow. She was assaulted with violence and indecency, and died in December 1911, after a painful illness, arising from her injuries. Henria Williams, already suffering from a weak heart, did not recover from the treatment she received that night in the Square, and died on January 1st."

The photograph of Ada Wright on the front page of The Daily Mirror the next day caused a great deal of embarrassment to the Home Office and the government demanded that the negative be destroyed. Wright told a reporter that she had been at seven suffragette demonstrations, but had "never known the police so violent."Charles Mansell-Moullin, who had helped treat the wounded claimed that the police had used "organised bands of well-dressed roughs who charged backwards and forwards through the deputations like a football team without any attempt being made to stop them by the police."

Sylvia Pankhurst believed that Winston Churchill, the Home Secretary, had encouraged this show of force. "Never, in all the attempts which we have made to carry our deputations to the Prime Minister, have I seen so much bravery on the part of the women and so much violent brutality on the part of the policeman in uniform and some men in plain clothes. It was at the same time a gallant and a heart-breaking sight to see those little deputations battling against overwhelming odds, and then to see them torn asunder and scattered, bruised and battered, against the organized gangs of rowdies. Happily, there were many true-hearted men in the crowd who tried to help the women, and who raised their hats and cheered them as they fought. I found out during the evening that the picked men of the A Division, who had always hitherto been called out on such occasions, were this time only on duty close to the House of Commons and at the police station, and that those with whom the women chiefly came into contact had been especially brought in from the outlying districts. During our conflicts with the A Division they had gradually come to know us, and to understand our aims and objects, and for that reason, whilst obeying their orders, they came to treat the women, as far as possible, with courtesy and consideration. But these men with whom we had to deal on Friday were ignorant and ill-mannered, and of an entirely different type. They had nothing of the correct official manner, and were to be seen laughing and jeering at the women whom they maltreated."

Churchill had been a long-term opponent of votes for women. As a young man he argued: "I shall unswervingly oppose this ridiculous movement (to give women the vote)... Once you give votes to the vast numbers of women who form the majority of the community, all power passes to their hands." His wife, Clementine Churchill, was a supporter of votes for women and after marriage he did become more sympathetic but was not convinced that women needed the vote. When a reference was made at a dinner party to the action of certain suffragettes in chaining themselves to railings and swearing to stay there until they got the vote, Churchill's reply was: "I might as well chain myself to St Thomas's Hospital and say I would not move till I had had a baby." However, it was the policy of the Liberal Party to give women the vote and so he could not express these opinions in public.

Henry Brailsford was commissioned to write a report Treatment of the Women's Deputations of November 18th, 22nd and 23rd, 1910, by the Police (1910) on Black Friday. He took testimony from a large number of women, including Mary Frances Earl: "In the struggle the police were most brutal and indecent. They deliberately tore my undergarments, using the most foul language - such language as I could not repeat. They seized me by the hair and forced me up the steps on my knees, refusing to allow me to regain my footing... The police, I understand, were brought specially from Whitechapel."

Paul Foot, the author of The Vote (2005) has pointed out, Brailsford and his committee obtained "enough irrefutable testimony not just of brutality by the police but also of indecent assault - now becoming a common practice among police officers - to shock many newspaper editors, and the report was published widely". However, Edward Henry, the Commissioner of the Metropolitan Police, claimed that the sexual assaults were committed by members of the public: "Amongst this crowd were many undesirable and reckless persons quite capable of indulging in gross conduct."

Under pressure from the National Union of Suffrage Societies and the Women's Social and Political Union and the in 1911 the Liberal government introduced the Conciliation Bill that was designed to conciliate the suffragist movement by giving a limited number of women the vote, according to their property holdings and marital status. According to Lucy Masterman, it was her husband, Charles Masterman, who provided the arguments against the legislation: "He (Churchill) is, in a rather tepid manner, a suffragist (his wife is very keen) and he came down to the Home Office intending to vote for the Bill. Charlie, whose sympathy with the suffragettes is rather on the wane, did not want him to and began to put to him the points against Shackleton's Bill - its undemocratic nature, and especially particular points, such as that 'fallen women' would have the vote but not the mother of a family, and other rhetorical points. Winston began to see the opportunity for a speech on these lines, and as he paced up and down the room, began to roll off long phrases. By the end of the morning he was convinced that he had always been hostile to the Bill and that he had already thought of all these points himself...He snatched at Charlie's arguments against this particular Bill as a wild animal snatches at its food."

Winston Churchill argued in the House of Commons: "The more I study the Bill the more astonished I am that such a large number of respected Members of Parliament should have found it possible to put their names to it. And, most of all, I was astonished that Liberal and Labour Members should have associated themselves with it. It is not merely an undemocratic Bill; it is worse. It is an anti-democratic Bill. It gives an entirely unfair representation to property, as against persons.... Of the 18,000 women voters it is calculated that 90,000 are working women, earning their living. What about the other half? The basic principle of the Bill is to deny votes to those who are upon the whole the best of their sex. We are asked by the Bill to defend the proposition that a spinster of means living in the interest of man-made capital is to have a vote, and the working man's wife is to be denied a vote even if she is a wage-earner and a wife.... What I want to know is how many of the poorest class would be included? Would not charwomen, widows, and others still be disfranchised by receiving Poor Law relief? How many of the propertied voters will be increased by the husband giving a £10 qualification to his wife and five or six daughters?"

David Lloyd George, the Chancellor of the Exchequer, was officially in favour of woman's suffrage. However, he was convinced that the chief effect of the Bill, if it became law, would be to hand more votes to the Conservative Party. During the debate on the Conciliation Bill he stated that justice and political necessity argued against enfranchising women of property but denying the vote to the working class. The following day Asquith announced that in the next session of Parliament he would introduce a Bill to enfranchise the four million men currently excluded from voting and suggested it could be amended to include women. Paul Foot has pointed out that as the Tories were against universal suffrage, the new Bill "smashed the fragile alliance between pro-suffrage Liberals and Tories that had been built on the Conciliation Bill."

Millicent Fawcett still believed in the good faith of the Asquith government. However, the WSPU, reacted very differently: "Emmeline and Christabel Pankhurst had invested a good deal of capital in the Conciliation Bill and had prepared themselves for the triumph which a women-only bill would entail. A general reform bill would have deprived them of some, at least, of the glory, for even though it seemed likely to give the vote to far more women, this was incidental to its main purpose."

Christabel Pankhurst wrote in Votes for Women that Lloyd George's proposal to give votes to seven million instead of one million women was, she said, intended "not, as he professes, to secure to women a larger measure of enfranchisement but to prevent women from having the vote at all" because it would be impossible to get the legislation passed by Parliament.

On 9th November 1911, the WSPU withdrew support for the Conciliation Bill. On 21st November, the WSPU carried out an "official" window smash along Whitehall and Fleet Street. This involved the offices of the Daily Mail and the Daily News and the official residences or homes of leading Liberal politicians such as H. H. Asquith, David Lloyd George, Winston Churchill, Edward Grey, John Burns and Lewis Harcourt. It was reported that "160 suffragettes were arrested, but all except those charged with window-breaking or assault were discharged."

In March 1912 she took part in a demonstration with Sarah Carwin, Olive Wharry, Margaret Macfarlane, Helen Craggs and Kitty Marion. Wright was "charged with the wanton destruction of private property, value £4,000 and was sentenced to six months imprisonment. Wright was one of those arrested for breaking Harcourt's windows in Berkeley Square. It was the fifth time in her suffragette career. Ada was sent to prison for two weeks; she wrote to a friend that the night before taking part in any militant event "the suspense always tries me terribly".

Ada Wright was accused of breaking windows of the Great Northern Railway Company in Charing Cross causing £9 worth of damage. This time she was sentenced to six months in Aylesbury Prison. (35) After going on hunger strike the prison doctor tried to put the feeding tube in her mouth Ada "clenched her teeth to prevent the tube from being pushed into her mouth". A steel gag was then used to prise open her jaws "and the tube was rammed down her throat by clumsy and unskilled fingers". Ada thought she would suffocate as this process made it difficult to breathe. This happened twice a day for ten days. Ada later recalled the wardresses being very distressed and often in tears having to help the doctor in his "gruesome task".

On 14th June 1913, Ada Wright sailed to the United States on RMS Carmania, to visit her brother Albert Evelyn Wright, who was living in Plainview, New Jersey. On her arrival she gave her occupation as "Women's Suffrage".

During the First World War she groomed post office horses, worked in canteens and drove hospital and drove hospital ambulances. After the war she was a social worker and on 18th June 1928 was a pall-bearer at the funeral of Emmeline Pankhurst. In the 1930s she cared for refugees who had fled from Nazi Germany.

Ada Cecile Granville Wright was living at 61 Granville Road, Finchley, when she died on 4th December 1939. She left effects valued at £24,580.

On the day in 1935 the German football team give the Nazi salute in game at White Hart Lane. In December 1935, Strength Through Joy arranged for 10,000 Germans to travel to London to watch their team play England at White Hart Lane. It was a curious choice of venue because within football Spurs are known as “the Jewish club” owing to support from Jewish communities in north London. There were also Jews among the players. On the day of the match a demonstration march converged on White Hart Lane. Leaflets printed in German were handed out by demonstrators and there were some minor scuffles with pro-Nazi sympathisers. Before the game the German players gave the nazi salute and the swastika was flown over the ground. England won the game 3-0.

On this day in 1969 civil rights leader Fred Hampton was murdered by the police. Fred Hampton was born in Chicago on 30th August 1948 and grew up in Maywood, a suburb of the city. A bright student, Hampton graduated from Proviso East High School in 1966 before enrolling at Triton Junior College where he studied law.

While a student Hampton became active in the civil rights movement. He joined the National Association for the Advancement of Coloured People (NAACP) and was appointed leader of the Youth Council of the organization's West Suburban branch.

In October 1966 Bobby Seale and Huey Newton formed the Black Panther Party in Oakland, California. Initially formed to protect local communities from police brutality and racism, the Black Panthers eventually developed into a Marxist revolutionary group. The group also ran medical clinics and provided free food to school children. Other important members included Stokely Carmichael, H. Rap Brown, Bobby Hutton and Eldridge Cleaver.

Hampton founded the Chicago chapter of the Black Panther Party in November 1968. He immediately established a community service program. This included the provision of free breakfasts for schoolchildren and a medical clinic that did not charge patients for treatment. Hampton also taught political education classes and instigated a community control of police project.

One of Hampton's greatest achievements was to persuade Chicago's most powerful street gangs to stop fighting against each other. In May 1969 Hampton held a press conference where he announced a nonaggression pact between the gangs and the formation of what he called a "rainbow coalition" (a multiracial alliance of black, Puerto Rican, and poor youths).

Later that year Hampton was arrested and charged with stealing $71 worth of sweets, which he then allegedly gave away to local children. Hampton was initially convicted of the crime but the decision was eventually overturned.

The activities of the Black Panthers in Chicago came to the attention of J. Edgar Hoover and the FBI. Hoover described the Panthers as "the greatest threat to the internal security of the country" and urged the Chicago police to launch an all-out assault on the organization. In 1969 the Panther party headquarters on West Monroe Street was raided three times and over 100 members were arrested.

In the early hours of the 4th December, 1969, the Panther headquarters was raided by the police for the fourth time. The police later claimed that the Panthers opened fire and a shoot-out took place. During the next ten minutes Fred Hampton and Mark Clark were killed. Witnesses claimed that Hampton was wounded in the shoulder and then executed by a shot to the head.

The panthers left alive, including Deborah Johnson, Hampton's girlfriend, who was eight months pregnant at the time, were arrested and charged with attempting to murder the police. Afterwards, ballistic evidence revealed that only one bullet had been fired by the Panthers whereas nearly a hundred came from police guns.

After the resignation of President Richard Nixon, the Senate Intelligence Committee conducted a wide-ranging investigation of America's intelligence services. Frank Church of Idaho, the chairman of the committee, revealed in April, 1976 that William O'Neal, Hampton's bodyguard, was a FBI agent-provocateur who, days before the raid, had delivered an apartment floor-plan to the Bureau with an "X" marking Hampton's bed. Ballistic evidence showed that most bullets during the raid were aimed at Hampton's bedroom.

On this day in 1975 philosopher Hannah Arendt died. Hannah, the daughter of Paul and Martha Arendt, was born in Hanover on 14th October 1906. Her father was a successful businessman but held progressive political opinions. Paul and Martha were both members of the German Social Democratic Party. Paul had been suffering from syphilis for many years and died in a psychiatric hospital in 1913 when Hannah was only seven. It has been claimed by Derwent May that "those who knew her well could see that Hannah kept a deep sorrow buried inside her."

Hannah's mother had no religious faith but she brought her daughter up to be proud of her Jewish heritage. She had little interest in tradition or ritual. Hannah felt that her dark brown eyes made her look a little different than other children. There was the odd anti-Semitic comment but anti-Semitism was not a serious problem in those years.

Hannah's mother made it clear how she respond to anti-Semitism: "When my teachers made anti-Semitic remarks - mostly not about me, but about other Jewish girls, eastern Jewish students in particular - I was told to get up immediately, leave the classroom, come home, and report everything exactly. Then my mother wrote one of her many registered letters; and for me the matter was completely settled. I had a day off from school, and that was marvelous! But when it came from children, I was not permitted to tell about it at home. That defended yourself against what came from children."

In 1920, when she was thirteen, her mother married again. Her new husband, Martin Beerwald, a successful Jewish businessman, had two teenage daughters (his first wife had died a few years before), Clara, who was now twenty, and Eva who was nineteen. They were all supporters of the Social Democratic Party and Hannah enjoyed the political discussions that took place in the family.

Hannah Arendt was an extremely intelligent teenager and became interested in Greek philosophy. "Headstrong and independent, she displayed a precocious aptitude for the life of the mind. And while she might risk confrontation with a teacher who offended her with an inconsiderate remark - she was briefly expelled for leading a boycott of the teacher's classes."

Hannah's fellow students found her a very attractive young woman. Hannah was described as having "striking looks: thick, dark hair, a long, oval face, and brilliant eyes". One student claimed that she had "lonely eyes" but "starry when she was happy and excited". Another friend described them as "deep, dark, remote pools of inwardness."

Arendt later recalled that life was difficult as a Jew living in Germany: "One thing was certain: if one wanted to avoid all ambiguities of social existence, one had to resign oneself to the fact that to be a Jew meant to belong either to an over privileged upper class or to an underprivileged mass which, in Western and Central Europe, one could belong to only through an intellectual and somewhat artificial solidarity."

At the age of sixteen, Martha Arendt, arranged for her to spend two terms studying in Berlin, where the family had friends. Hannah lived in a student residence and took classes in Latin and Greek at the university, where she was introduced to theology by Romano Guardini, a Christian existentialist, who introduced her to the work of Søren Kierkegaard and Karl Jaspers.

At the age of sixteen, Martha Arendt, arranged for her to spend two terms studying in Berlin, where the family had friends. Hannah lived in a student residence and took classes in Latin and Greek at the university, where she was introduced to theology by Romano Guardini, a Christian existentialist, who introduced her to the work of Søren Kierkegaard and Karl Jaspers.

In the summer of 1925, Hannah relationship with Martin Heidegger began to weaken. In a letter to him she explained the way she was feeling. Derwent May explained: "After her happy childhood, she says that she had become dull and self-preoccupied for a long time. noticing things but not responding to them with any feeling, and finding a protection for herself in this state of mind. Heidegger had released her from this spell, so that the world had become full of colour and fascination and mystery for her again."

Hannah Arendt left University of Marburg and moved to the University of Freiburg, where she studied under Edmund Husserl, a man who had inspired Heidegger's philosophy. Husserl was very impressed with Heidegger recent work and wrote to Erich Jaensch saying. "He is without doubt the most important figure among the rising generation of philosophers... predestined to be a philosopher of great stature, a leader far beyond the confusions and frailties of the present age."

Arendt wrote that Heidegger recognised before anyone else that philosophy was almost dead. It had been formulated into schools of thought and compartmentalized into such disciplines such as logic, ethics, and epistemology, and was not so much taught as "finished off by abysmal boredom." Heidegger did not participate in the "endless chatter about philosophy," rehearsing the teachings of others. He read all the earlier thinkers, and he read them, Arendt said, better than anyone ever had, and perhaps better than anyone ever will again. "His intention was not merely to comprehend or absorb the lessons taught by others, but to interrogate the masters, to think with and against them."

On 9th January, 1926, Arendt visited Heidegger and complained that she felt forgotten. In a letter to Arendt he tried to explain his position: "It is not from indifference, not because external circumstance intruded between us, but because I had to forget and will forget you whenever I withdraw into the final stages of my work. This is not a matter of hours or days, but a process that develops over weeks and months and then subsides. And this withdrawal from everything human and breaking off of all connections is, with regard to creative work, the most magnificent human experience... but with regard to concrete situations, it is the most repugnant thing one can encounter. One's heart is ripped from one's body."