On this day on 24th February

On this day in 1809 London's Drury Lane Theatre burns to the ground. It's owner Richard Brinsley Sheridan on being encountered drinking a glass of wine in the street while watching the fire, he famously reported to have said: "A man may surely be allowed to take a glass of wine by his own fireside." Already on the shakiest financial ground, Sheridan was ruined entirely by the loss of the building.

Sheridan asked his wealthy friend, Samuel Whitbread for help. Whitbread agreed to head a committee that would manage the company and oversee the rebuilding of the theatre, but asked Sheridan to withdraw from management himself, which he did entirely by 1811.

Sheridan was born in Dublin on 30th October 1751. Sheridan's parents moved to London and in 1762 he was sent to Harrow School. After six years at Harrow he went to live with his father in Bath who had found employment there as an elocution teacher.

In March 1772 Sheridan eloped to France with a young woman called Elizabeth Linley. A marriage ceremony was carried out at Calais but soon afterwards the couple were caught by the girl's father. As a result of this behaviour, Sheridan was challenged to a duel. The fight took place on 2nd July 1772, during which Sheridan was seriously wounded. However, Sheridan recovered and after qualifying as a lawyer, Mr. Linley gave permission for the couple to marry.

Sheridan began writing plays and on 17th January, 1775, the Covent Garden Theatre produced his comedy, The Rivals. After a poor reception it was withdrawn. A revised version appeared soon after and it eventually become one of Britain's most popular comedies. Two other plays by Sheridan, St Patrick's Day and The Duenna, were also successfully produced at the Covent Garden Theatre. In 1776 Sheridan joined with his father-in-law to purchase the Drury Lane Theatre for £35,000. The following year he produced his most popular comedy, The School for Scandal.

In 1776 Sheridan met Charles Fox, the leader of the Radical Whigs in the House of Commons. Sheridan now decided to abandon his writing in favour of a political career. On 12th September, 1780, Sheridan became MP for Stafford. Sheridan was a frequent speaker in the House of Commons and soon obtained a reputation as one of the best orators in Britain. Sheridan was a strong critic of Lord North's American policy and supported the resistance of the colonists. Congress was so grateful for Sheridan's support that he was offered a reward of £20,000. Under attack for disloyalty to his country, Sheridan decided not to accept the gift.

In 1782 the Marquis of Rockingham appointed Sheridan as his under secretary for Foreign Affairs. The following year he served in the coalition ministry headed by William Pitt. Sheridan retained his radical political beliefs and in 1794 defended the French Revolution against its critics in the House of Commons. Despite his disapproval of some aspects of the new regime, Sheridan argued that the French people had the right to form their own form of government without outside interference.

Sheridan was also a strong supporter of an uncensored press and argued strenuously against attempts to use the libel laws to prevent criticism of the government. In 1798 he argued: "The press should be unfettered, that its freedom should be, as indeed it was, commensurate with the freedom of the people and the well-being of a virtuous State; on that account even one hundred libels had better be ushered into the world than one prosecution be instituted which might endanger the liberty of the press of this country."

Sheridan opposed the Act of Union with Ireland and lost office when Henry Addington replaced William Pitt as Prime Minister. Sheridan refused Addington's offer of a peerage in return for supporting the Tories with the words that he had "an unpurchasable mind". Sheridan remained remained a devoted follower of Charles Fox, until his death in 1806.

In 1806 Sheridan returned to the government as treasurer of the navy. However, he was defeated in the the general election of 1807 but soon afterwards found a seat at Ilchester. In 1812 Sheridan attempted to win his old seat of Stafford, but unable to raise the money to pay the normal fee of five guineas per voter, he was defeated. Sheridan had serious financial problems and in August, 1813 was arrested for debt. Sheridan was only released when his wealthy friend, Samuel Whitbread handed over the sum required.

Richard Brinsley Sheridan died in great poverty on 7th July 1816.

On this day in 1827 Lydia Becker, the daughter of Hannibal Becker, the owner of a chemical works in Manchester, and Mary Duncuft, was born. The eldest of fifteen children, Lydia, like the rest of her sisters, was educated at home. After the death of her mother in 1855, Lydia had the responsibility of looking after her younger brothers and sisters.

Lydia developed an interest in botany and in 1864 won an award for her collection of dried plants and in 1866 her book Botany for Novices, was published. The following year Lydia founded the Manchester's Ladies Literacy Society, which despite its name was intended as a society to study scientific matters."

In 1866 Lydia heard Barbara Bodichon give a lecture on women's suffrage at a meeting in Manchester. She was immediately converted to the idea that women should have the vote and wrote an article Female Suffrage for the magazine, The Contemporary Review. Emily Davies and Elizabeth Wolstenholme were two of the women who read the article and later that year they joined with Lydia Becker to form the Manchester Women's Suffrage Committee. Wolstenholme then arranged to have 10,000 copies of the article printed as a pamphlet.

In the House of Commons the Radical MP, John Stuart Mill campaigned with Henry Fawcett and Peter Alfred Taylor for parliamentary reform and in 1866 presented the petition organised by Barbara Bodichon, Emily Davies, Elizabeth Garrett and Dorothea Beale in favour of women's suffrage. Mill, added an amendment to the 1867 Reform Act that would give women the same political rights as men. However, the amendment was defeated by 196 votes to 73.

During the debate on Mill's amendment, Edward Kent Karslake, the Conservative MP for Colchester, said in the House of Commons that the main reason he opposed the measure was that he had not met one woman in Essex who agreed with women's suffrage. Lydia Becker, Helen Taylor and Frances Power Cobbe, decided to take up this challenge and devised the idea of collecting signatures in Colchester for a petition that Karslake could then present to parliament. They found 129 women resident in the town willing to sign the petition and on 25th July, 1867, Karslake presented the list to parliament. Despite this petition the Mill amendment was defeated by 196 votes to 73.

In 1868 Lydia Becker became treasurer of the Married Women's Property Committee and also joined Josephine Butler in her campaign against the Contagious Diseases Acts. Becker continued to write articles about the need for parliamentary reform and in 1870 she established the Women's Suffrage Journal. Becker was also involved in other feminist campaigns.

The 1870 Education Act allowed women to vote and serve on School Boards. Lydia Becker was elected to the Manchester School Board where she took a strong interest in improving the education of girls in the city. Becker criticised the domestic education of girls in Manchester's schools and argued that boys should be taught to mend their own socks and cook their own meals.

In 1874 William Forsyth MP announced he was willing to promote a bill that would grant single, but not married women, the vote. Becker, who was unmarried, created a controversy in the suffrage movement when she supported this proposal. Although Becker only suggested this as a short-term strategy, some married suffragists, such as Emmeline Pankhurst, were outraged by her views. Later that year Becker was forced to resign from the Married Women's Property Committee.

In 1881 Becker received a letter from the Central Society for Women's Suffrage offering her the post of paid secretary of the organisation. She held the post for the next three years. Becker was elected as president of National Union of Women's Suffrage Societies (NUWSS) in 1887.

Becker's biographer, Linda Walker, has argued: "As a public speaker she lacked oratorical flair, but was noted for persuasiveness and clarity of thought; she undertook onerous lecture tours at a time when it was thought unseemly for a lady to appear on a public platform. Physically stout from early womanhood, her broad, flat face, wire-rimmed spectacles, and plaited crown of hair were a cartoonist's delight, and she was much lampooned in the popular press. However, she quickly gained recognition as the movement's key strategist, directing national policy and tactics with a statesmanlike mind: the women-only great demonstrations held throughout the country in 1880 attracted capacity crowds and enormous publicity for the cause."

By the end of 1889 Becker's health began to fail and Helen Blackburn replaced her as editor of the Women's Suffrage Journal . Becker took medical advice to visit the health resort of Aix-les-Bains. While Lydia Becker was there she caught diphtheria and died on 21st July 1890.

On this day in 1828 John Betts sent a letter to Richard Carlile about child labour. "In 1805 when Samuel Davy was seven years of age he was sent from the workhouse in Southwark in London to Mr. Watson's Mill at Penny Dam near Preston. Later his brother was also sent to work in a mill. The parents did not know where Samuel and his brother were. The loss of her children, so preyed on the mind of Samuel's mother that it brought on insanity, and she died in a state of madness."

Many parents were unwilling to allow their children to work in these new textile factories. To overcome this labour shortage factory owners had to find other ways of obtaining workers. One solution to the problem was to buy children from orphanages and workhouses. The children became known as pauper apprentices. This involved the children signing contracts that virtually made them the property of the factory owner.

John Brown, the author of Robert Blincoe's Memoir, explained how eighty children were taken from St. Pancras Workhouse: "In the summer of 1799 a rumour circulated that there was going to be an agreement between the church wardens and the overseers of St. Pancras Workhouse and the owner of a great cotton mill, near Nottingham. The children were told that when they arrived at the cotton mill, they would be transformed into ladies and gentlemen: that they would be fed on roast beef and plum pudding, be allowed to ride their masters' horses, and have silver watches, and plenty of cash in their pockets. In August 1799, eighty boys and girls, who were seven years old, or were considered to be that age, became parish apprentices till they had acquired the age of twenty-one."

Robert Blincoe was disappointed when he arrived at Lowdam Mill, ten miles from Nottingham. "There was no cloth laid on the tables, to which the newcomers had been accustomed in the workhouse - no plates, nor knives, nor forks. At a signal given, the apprentices rushed to this door, and each, as he made way, received his portion, and withdrew to his place at the table. Blincoe was startled, seeing the boys pull out the fore-part of their shirts, and holding it up with both hands, received the hot boiled potatoes allotted for their supper. The girls, less indecently, held up their dirty, greasy aprons, that were saturated with grease and dirt, and having received their allowance, scampered off as hard as they could, to their respective places, where, with a keen appetite, each apprentice devoured her allowance, and seemed anxiously to look about for more. Next, the hungry crew ran to the tables of the newcomers, and voraciously devoured every crust of bread and every drop of porridge they had left."

Pauper apprentices were cheaper to house than adult workers. It cost Samuel Greg who owned the large Quarry Bank Mill at Styal, a £100 to build a cottage for a family, whereas his apprentice house, that cost £300, provided living accommodation for over 90 children. At first the children came from local parishes such as Wilmslow and Macclesfield, but later he went as far as Liverpool and London to find these young workers. To encourage factory owners to take workhouse children, people like Greg were paid between £2 and £4 for each child they employed. Greg also demanded that the children were sent to him with "two shifts, two pairs of stockings and two aprons".

The same approach was taken by the owners of silk mills. George Courtauld, who owned a silk mill in Braintree, Essex, took children from workhouses in London. Although offered children of all ages he usually took them from "within the age of 10 and 13". Courtauld insisted that each child arrived "with a complete change of common clothing". A contract was signed with the workhouse that stated that Courtauld would be paid £5 for each child taken. Another £5 was paid after the child's first year. The children also signed a contract with Courtauld that bound them to the mill until the age of 21. This helped to reduce Courtauld's labour costs. Whereas adult males at Courtauld's mills earned 7s. 2d., children under 11 received only 1s. 5d. a week.

Owners of large textile mills purchased large numbers of children from workhouses in all the large towns and cities. By the late 1790s about a third of the workers in the cotton industry were pauper apprentices. Child workers were especially predominant in large factories in rural areas. For example, in 1797, of the 310 wortkers employed by Birch Robinson & Co in the village of Backbarrow, 210 were parish apprentices. However, in the major textile towns, such as Manchester and Oldham, parish apprenticeships was fairly uncommon.

On this day in 1836 Winslow Homer was born in Boston, Massachusetts. When he was nineteen he was apprenticed as to the lithographic firm of John Bufford. In 1859 he moved to New York where he worked as a freelance illustrator.

On the outbreak of the American Civil War Homer was sent by Harper's Weekly, to draw pictures of the fighting. He observed the battle of Bull Run before accompanying the Army of the Potomac during its Peninsula Campaign. He also drew pictures of the siege of Petersburg.

During the war Homer developed a reputation for realism and this was reinforced with paintings such as, In Front of Yorktown, Playing Old Soldier, A Rainy Day in Camp and A Skirmish in the Wilderness. His best known picture during this period, was the highly acclaimed, Prisoners from the Front (1866).

Although Homer owned a studio in New York he travelled widely, including in the Deep South, where he painted The Cotton Pickers (1876) and Dressing for the Carnival (1877).

After living in Tynemouth, a small fishing village in England (1881-82) he returned to the United States and settled at Prouts Neck, on the coast of Maine. Over the next year he concentrated on seascapes such as The Gulf Stream (1899), Moonlight - Wood's Island Light (1886), Northeaster (1895) and Early Morning After a Storm at Sea (1902).

Winslow Homer died on 29th September, 1910.

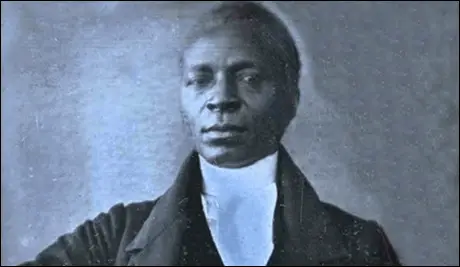

On this day in 1842 James Forten died. Forten was born in Philadelphia in 1766. Apprenticed as a sailmaker he became a foreman in 1786 and by 1798 he owned his own company in 1798. A successful businessman he amassed a fortune of over $100,000.

Forten took an active interest in politics and campaigned for temperance, women's suffrage and equal rights for African-Americans. In 1800 he organised a petition calling for Congress to emancipate all slaves. He also wrote and published a pamphlet attacking the Pennsylvania legislature for prohibiting the immigration of freed black slaves from other states.

In 1817 Forden joined with Richard Allen to form the Convention of Color. The organization argued for the settlement of escaped black slaves in Canada but was strongly opposed to any plans for repatriation to Africa. Other leading figures that became involved in the movement was William Wells Brown, Samuel Eli Cornish and Henry Highland Garnet.

In 1833 Forten helped to form the American Anti-Slavery Society. A close friend of William Lloyd Garrison, Forten contributed to his anti-slavery newspaper, The Liberator.

On this day in 1855 the Illustrated London News publish an article on Florence Nightingale on working in Scutari. "Although the public have been presented with several portrait-sketches of the lady who has so generously left this country to attend to the sufferings of the sick and wounded at Constantinople, we have assurance that these pictures are "singularly and painfully unlike". We have, therefore, taken the most direct means of obtaining a sketch of this excellent lady, in the dress she now wears, in one of the corridors of the sick".

In March, 1853, Russia invaded Turkey. Britain and France, concerned about the growing power of Russia, went to Turkey's aid. This conflict became known as the Crimean War. Soon after British soldiers arrived in Turkey, they began going down with cholera and malaria. Within a few weeks an estimated 8,000 men were suffering from these two diseases.

William Howard Russell, who worked for The Times, reported the Siege of Sevastopol. He found Lord Raglan uncooperative and wrote to his editor, John Thadeus Delane alleging unfairly that "Lord Raglan is utterly incompetent to lead an army". Roger T. Stearn has argued: "Unwelcomed and obstructed by Lord Raglan, senior officers (except de Lacy Evans), and staff, yet neither banned, controlled, nor censored, William Russell made friends with junior officers, and from them and other ranks, and by observation, gained his information. He wore quasi-military clothes and was armed, but did not fight. He was not a great writer but his reports were vivid, dramatic, interesting, and convincing.... His reports identified with the British forces and praised British heroism. He exposed logistic and medical bungling and failure, and the suffering of the troops."

Russell's reports revealled the sufferings of the British Army during the winter of 1854-1855. These accounts upset Queen Victoria who described them as these "infamous attacks against the army which have disgraced our newspapers". Prince Albert, who took a keen interest in military matters, commented that "the pen and ink of one miserable scribbler is despoiling the country." Lord Raglan complained that Russell had revealed military information potentially useful to the enemy.

William Howard Russell reported that British soldiers began going down with cholera and malaria. Within a few weeks an estimated 8,000 men were suffering from these two diseases. When Mary Seacole heard about the cholera epidemic she travelled to London to offer her services to the British Army. There was considerable prejudice against women's involvement in medicine and her offer was rejected. When Russell publicised the fact that a large number of soldiers were dying of cholera there was a public outcry, and the government was forced to change its mind. Florence Nightingale volunteered her services and was eventually given permission to take a group of thirty-eight nurses to Turkey.

Nightingale found the conditions in the army hospital in Scutari appalling. The men were kept in rooms without blankets or decent food. Unwashed, they were still wearing their army uniforms that were "stiff with dirt and gore". In these conditions, it was not surprising that in army hospitals, war wounds only accounted for one death in six. Diseases such as typhus, cholera and dysentery were the main reasons why the death-rate was so high amongst wounded soldiers.

Edward T. Cook, the author of The Life of Florence Nightingale (1913), quoted one of the men in the hospital that she treated: "Florence Nightingale is a ministering angel without any exaggeration in these hospitals, and as her slender form glides quietly along each corridor, every poor fellow's face softens with gratitude at the sight of her. When all the medical officers have retired for the night and silence and darkness have settled down upon those miles of prostrate sick, she may be observed alone, with a little lamp in her hand, making her solitary rounds."

Military officers and doctors objected to Nightingale's views on reforming military hospitals. They interpreted her comments as an attack on their professionalism and she was made to feel unwelcome. Florence Nightingale received very little help from the military until she used her contacts at The Times to report details of the way that the British Army treated its wounded soldiers. John Delane, the editor of newspaper took up her cause, and after a great deal of publicity, Nightingale was given the task of organizing the barracks hospital after the battle of Inkerman and by improving the quality of the sanitation she was able to dramatically reduce the death-rate of her patients.

Sidney Herbert wrote "There broke out in different parts of the country a feeling of immediate and spontaneous expression of public gratitude and isolated portions of the country were preparing to make gifts to her." Charles Dickens and Angela Burdett-Coutts were two people who wished to contribute. Nightingale had spoken about the "sodden misery in the hospital". On Dickens's advice, at the end of January 1855, Burdett-Coutts ordered from William Jeakes, an engineer working in Bloomsbury, a drying closet machine. It was built at a cost of £150. It was shipped out in parts and re-assembled in Istanbul.

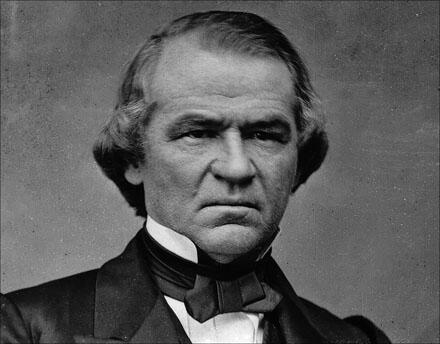

On this day in 1868 Andrew Johnson becomes the first President of the United States to be impeached. Abraham Lincoln originally selected General Benjamin Butler as his 1864 vice-presidential candidate. Butler, a war hero, had been a member of the Democratic Party, but his experiences during the American Civil War had made him increasingly radical. Simon Cameron was sent to talk to Butler at Fort Monroe about joining the campaign. However, Butler rejected the offer, jokingly saying that he would only accept if Lincoln promised "that within three months after his inauguration he would die".

It was now decided that Johnson would make the best candidate for vice president. By choosing the governor of Tennessee, Lincoln would emphasis the fact that Southern states were still part of the Union. He would also gain the support of the large War Democrat faction. At a convention of the Republican Party on 8th July, 1864, Johnson received 200 votes to Hamlin's 150 and became Lincoln's running mate.

During the election Johnson made it clear that he supported what he called "white man's government". However, when faced with black audiences he spoke of the need of improved civil rights and on one occasion during a speech in Washington offered to "be your Moses and lead you through the Red Sea of war and bondage to a fairer future of liberty and peace."

The military victories of Ulysses S. Grant, William Sherman, George Meade, Philip Sheridan and George H. Thomas in the American Civil War in 1864 reinforced the idea that the Union Army was close to bringing the war to an end. This helped Lincoln's presidential campaign and with 2,216,067 votes, Lincoln comfortably beat General George McClellan (1,808,725) in the election.

Andrew Johnson had been a heavy drinker for several years. Both his sons, Charles and Robert, were alcoholics. Charles Johnson died in April 1863 after falling from his horse. Colonel Robert Johnson, a member of the Union Army, was found to be drunk while on duty and was sent home in order to avoid further embarrassment to the Vice President.

On inauguration day Johnson was drunk while he made his speech to Congress. After making several inappropriate comments Hannibal Hamlin, the former Vice President had to intervene and help him back to his seat. After the inauguration, one of the senators, Zachariah Chandler, wrote to his wife that Johnson "was too drunk to perform his duties and disgraced himself and the Senate by making a drunken foolish speech."

On 14th April, 1865 Abraham Lincoln went to Ford's Theatre with his wife, Mary Lincoln, Clara Harris and Major Henry Rathbone to see a play called Our American Cousin. John Parker, a constable in the Washington Metropolitan Police Force, was detailed to sit on the chair outside the presidential box. During the third act Parker left to get a drink. Soon afterwards, John Wilkes Booth, entered Lincoln's box and shot the president in the back of the head. William Seward (Secretary of State) was also attacked by one of Booth's fellow conspirators, Lewis Paine. Another friend of Booth's, George Atzerodt, had been ordered to kill Johnson. Despite making the necessary preparations he surprisingly made no attempt to do this.

Abraham Lincoln died at 7.22 on the morning of 15th April. Three hours later Chief Justice Salmon Chase administered the oath of office at Johnson's Kirkwood House. Later that day a group of Radical Republicans led by Benjamin Wade met with Johnson. It was suggested that Henry G. Stebbins, John Covode and Benjamin Butler should be appointed to the Cabinet to make sure that laws would be passed that would benefit former slaves in the South.

Johnson was unwilling to change the Cabinet he had inherited from Abraham Lincoln. This included William Seward (Secretary of State), Henry McCulloch (Secretary of the Treasury), Edwin M. Stanton (Secretary of War), Gideon Welles (Secretary of the Navy), James Speed (Attorney General), John Usher (Secretary of the Interior) and William Dennison (Postmaster General).

However, Johnson insisted that he intended to punish leading Confederates: "Robbery is a crime; rape is a crime; treason is a crime; and crime must be punished. The law provides for it; the courts are open. Treason must be made infamous and traitors punished." After these discussions Benjamin Wade told Johnson that he total faith in his new administration.

On 17th April Johnson received a deputation led by John Mercer Langston, the president of the National Rights League. Langston was a strong supporter of universal male suffrage and like the Radical Republicans left the meeting satisfied with the response of the new president. Johnson also had visits from other progressives such as Robert Dale Owen and Carl Schurz who advocated racial equality.

On 1st May, 1865, President Andrew Johnson ordered the formation of a nine-man military commission to try the conspirators involved in the assassination of Lincoln. It was argued by Edwin M. Stanton, the Secretary of War, that the men should be tried by a military court as Lincoln had been Commander in Chief of the army. Several members of the cabinet, disapproved, preferring a civil trial. However, James Speed, the Attorney General, agreed with Stanton and therefore the defendants did not enjoy the advantages of a jury trial.

The trial began on 10th May, 1865. The military commission included leading generals such as David Hunter, Lewis Wallace, Robert Foster, August Kautz, Thomas Harris and Albion Howe. The Attorney General selected Joseph Holt and John Bingham as the government's chief prosecutors.

Mary Surrat, Lewis Paine, George Atzerodt, David Herold, Samuel Mudd, Michael O'Laughlin, Edman Spangler and Samuel Arnold were all charged with conspiring to murder Lincoln. During the trial Joseph Holt and John Bingham attempted to persuade the military commission that Jefferson Davis and the Confederate government had been involved in conspiracy.

Joseph Holt attempted to obscure the fact that there were two plots: the first to kidnap and the second to assassinate. It was important for the prosecution not to reveal the existence of a diary taken from the body of John Wilkes Booth. The diary made it clear that the assassination plan was established just before the act took place. The defence surprisingly did not call for Booth's diary to be produced in court.

On 29th June, 1865 Mary Surratt, Lewis Powell, George Atzerodt, David Herold, Samuel Mudd, Michael O'Laughlin, Edman Spangler and Samuel Arnold were found guilty of being involved in the conspiracy to murder Lincoln. Surratt, Powell, Atzerodt and Herold were hanged at Washington Penitentiary on 7th July, 1865. Surratt, who was expected to be reprieved, was the first woman in American history to be executed. Later Joseph Holt claimed that Johnson surprisingly ignored the Military Commission's plea for mercy.

The Radical Republicans became concerned when Johnson began surrounding himself with advisers such as Preston King, Henry W. Halleck and Winfield S. Hancock, who were well known for their reactionary views. Johnson also began to clash with those cabinet members such as Edwin M. Stanton, William Dennison and James Speed who favoured the granting of black suffrage. In this he was supported by conservatives in the government such as Gideon Welles and and Henry McCulloch.

Southern politicians began to realize that Andrew Johnson was going to use his position to prevent reform taking place. One Confederate senator, Benjamin Hill, wrote from his prison cell: "By this wise and noble statesmanship you have become the benefactor of the Southern people in the hour of their direst extremity and entitled yourself to the gratitude of those living and those yet to live."

Johnson now began to argue that African American men should only be given the vote when they were able to pass some type of literacy test. He advised William Sharkey, the governor of Mississippi, that he should only "extend the elective franchise to all persons of color who can read the Constitution of the United States in English and write their names, and to all persons of color who own real estate valued at not less than two hundred and fifty dollars."

In early 1865 General William T. Sherman set aside a coastal strip in South Carolina, Georgia and Florida for the exclusive use of former slaves. A few months later, General Oliver Howard, the head of the new Freeman's Bureau, issued a circular regularizing the return of lands to previous owners but exempting those lands that were already being cultivated by freeman. Johnson was furious with Sherman and Howard for making these decisions and over-ruled them.

Johnson also upset radicals and moderates in the Republican Party when he issued an amnesty proclamation exempting fourteen classes from prosecution for their actions during the American Civil War. This included high military, civil, and judicial officers of the Confederacy, officers who had surrendered their commissions in the armed forces of the United States, war criminals and those with taxable property of more than $20,000. Vice President Alexander Stephens was one of those that Johnson pardoned.

Johnson became increasingly hostile to the work of General Oliver Howard and the Freeman's Bureau. Established by Congress on 3rd March, 1865, the bureau was designed to protect the interests of former slaves. This included helping them to find new employment and to improve educational and health facilities. In the year that followed the bureau spent $17,000,000 establishing 4,000 schools, 100 hospitals and providing homes and food for former slaves.

In early 1866 Lyman Trumbull introduced proposals to extend the powers of the Freeman's Bureau . When this measure was passed by Congress it was vetoed by Johnson. However, the Radical Republicans were able to gain the support of moderate members of the Republican Party and Johnson's objections were overridden by Congress.

In April 1866, Johnson also vetoed the Civil Rights Bill that was designed to protect freed slaves from Southern Black Codes (laws that placed severe restrictions on freed slaves such as prohibiting their right to vote, forbidding them to sit on juries, limiting their right to testify against white men, carrying weapons in public places and working in certain occupations). On 6th April, Johnson's veto was overridden in the Senate by 33 to 15.

Johnson told Thomas C. Fletcher, the governor of Missouri: "This is a country for white men, and by God, as long as I am President, it shall be a government for white men." His views on racial equality was clearly defined in a letter to Benjamin B. French, the commissioner of public buildings: "Everyone would, and must admit, that the white race was superior to the black, and that while we ought to do our best to bring them up to our present level, that, in doing so, we should, at the same time raise our own intellectual status so that the relative position of the two races would be the same."

Johnson's unwillingness to promote African American civil rights in the South upset the radical members of his Cabinet. In 1866 William Dennison (Postmaster General), James Speed (Attorney General) and James Harlan (Secretary of the Interior) all resigned. They were all replaced by the conservatives Alexander Randall (Postmaster General), Henry Stanbury (Attorney General) and Orville Browning (Secretary of the Interior).

In June, 1866, the Radical Republicans managed to persuade Congress to pass the Fourteenth Amendment of the Constitution. The amendment was designed to grant citizenship to and protect the civil liberties of recently freed slaves. It did this by prohibiting states from denying or abridging the privileges or immunities of citizens of the United States, depriving any person of his life, liberty, or property without due process of law, or denying to any person within their jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws.

The elections of 1866 increased the the Republican Party two-thirds majority in Congress. There were also a larger number of Radical Republicans and in March, 1867, Congress passed the Tenure of Office Act. This act forbade the President to remove any officeholder, including Cabinet members, who had been appointed with Senate consent. Once again Johnson attempted to veto the act.

In 1867 members of Radical Republicans such as Benjamin Loan, James Ashley and Benjamin Butler, began claiming in Congress that Johnson had been involved in the conspiracy to murder Abraham Lincoln. Butler asked the question: "Who it was that could profit by assassination (of Lincoln) who could not profit by capture and abduction? He followed this with: "Who it was expected by the conspirators would succeed to Lincoln, if the knife made a vacancy?" He also implied that Johnson had been involved in tampering with the diary of John Wilkes Booth. "Who spoliated that book? Who suppressed that evidence?"

Much was made of the fact that John Wilkes Booth had visited Johnson's house on the day of the assassination and left his card with the message: "Don't wish to disturb you. Are you at home?" Some people claimed that Booth was trying to undermine Johnson in his future role as president by implying he was involved in the plot. However, as his critics pointed out, this was unnecessary as it was Booth's plan to have Johnson killed by George Atzerodt at the same time that Abraham Lincoln was being assassinated.

On 7th January, 1867, James Ashley charged Johnson with the "usurpation of power and violation of law by corruptly using the appointing, pardoning, and veto powers, by disposing corruptly of the property of the United States, and by interfering in elections." Congress responded by referring Ashley's resolution to the Judiciary Committee.

Congress passed the first Reconstruction Acts on 2nd March, 1867. The South was now divided into five military districts, each under a major general. New elections were to be held in each state with freed male slaves being allowed to vote. The act also included an amendment that offered readmission to the Southern states after they had ratified the Fourteenth Amendment and guaranteed adult male suffrage. Johnson immediately vetoed the bill but Congress repassed the bill the same day.

Johnson consulted General Ulysses S. Grant before selecting the generals to administer the military districts. Eventually he appointed John Schofield (Virginia), Daniel Sickles (the Carolinas), John Pope (Georgia, Alabama and Florida), Edward Ord (Arkansas and Mississippi) and Philip Sheridan (Louisiana and Texas).

It soon became clear that the Southern states would prefer military rule to civil government based on universal male suffrage. Congress therefore passed a supplementary Reconstruction Act on 23rd March that authorized military commanders to supervise elections and generally to provide the machinery for constituting new governments. Once again Johnson vetoed the act on the grounds that it interfered with the right of the American citizen to "be left to the free exercise of his own judgment when he is engaged in the work of forming the fundamental law under which he is to live."

Radical Republicans were growing increasing angry with Johnson over his attempts to veto the extension of the Freeman's Bureau, the Civil Rights Bill and the Reconstruction Acts. This became worse when Johnson dismissed Edwin M. Stanton, his Secretary of War, and the only radical in his Cabinet and replaced him with Ulysses S. Grant. Stanton refused to go and was supported by the Senate. Grant now stood down and was replaced by Lorenzo Thomas.This was a violation of the Tenure of Office Act and some members of the Republican Party began talking about impeaching Johnson.

At the beginning of the 40th Congress Benjamin Wade became the new presiding officer of the Senate. As Johnson did not have a vice-president this meant that Wade was now the legal successor to the president. This was highly significant as attempts to impeach the president had already began.

Johnson continued to undermine the Reconstruction Acts. This included the removal of two of the most radical military governors. Daniel Sickles (the Carolinas) and Philip Sheridan (Louisiana and Texas) were replaced them with Edward Canby and Winfield Hancock.

In November, 1867, the Judiciary Committee voted 5-4 that Johnson be impeached for high crimes and misdemeanors. The majority report written by George H. Williams contained a series of charges including pardoning traitors, profiting from the illegal disposal of railroads in Tennessee, defying Congress, denying the right to reconstruct the South and attempts to prevent the ratification of the Fourteenth Amendment.

On 30th March, 1868, Johnson's impeachment trial began. Johnson was the first president of the United States to be impeached. The trial, held in the Senate in March, was presided over by Chief Justice Salmon Chase. Johnson was defended by his former Attotney General, Henry Stanbury, and William M. Evarts. One of Johnson's fiercest critics, Thaddeus Stevens was mortally ill, but he was determined to take part in the proceedings and was carried to the Senate in a chair.

Charles Sumner, another long-time opponent of Johnson led the attack. He argued that: "This is one of the last great battles with slavery. Driven from the legislative chambers, driven from the field of war, this monstrous power has found a refuge in the executive mansion, where, in utter disregard of the Constitution and laws, it seeks to exercise its ancient, far-reaching sway. All this is very plain. Nobody can question it. Andrew Johnson is the impersonation of the tyrannical slave power. In him it lives again. He is the lineal successor of John C. Calhoun and Jefferson Davis; and he gathers about him the same supporters."

Although a large number of senators believed that Johnson was guilty of the charges, they disliked the idea of Benjamin Wade becoming the next president. Wade, who believed in women's suffrage and trade union rights, was considered by many members of the Republican Party as being an extreme radical. James Garfield warned that Wade was "a man of violent passions, extreme opinions and narrow views who was surrounded by the worst and most violent elements in the Republican Party."

Others Republicans such as James Grimes argued that Johnson had less than a year left in office and that they were willing to vote against impeachment if Johnson was willing to provide some guarantees that he would not continue to interfere with Reconstruction.

When the vote was taken all members of the Democratic Party voted against impeachment. So also did those Republicans such as Lyman Trumbull, William Fessenden and James Grimes, who disliked the idea of Benjamin Wade becoming president. The result was 35 to 19, one vote short of the required two-thirds majority for conviction. The editor of The Detroit Post wrote that "Andrew Johnson is innocent because Ben Wade is guilty of being his successor."

A further vote on 26th May, also failed to get the necessary majority needed to impeach Johnson. The Radical Republicans were angry that not all the Republican Party voted for a conviction and Benjamin Butler claimed that Johnson had bribed two of the senators who switched their votes at the last moment.

On 25th July, 1868 Johnson vetoed the decision by Congress to extend the activities of the Freeman's Bureau for another year. Once again Johnson decision was speedily overturned. Johnson critics claimed that he had taken these decisions in an attempt to win the Democratic Party nomination. The party approved Johnson's actions but chose Horatio Seymour as its presidential candidate.

Johnson continued to issue pardons for people who had participated in the rebellion. By the end of his period in office he gave 13,350 pardons, including one for Jefferson Davis, the president of the Confederacy during the American Civil War.

On 25th December, 1868, Johnson used his last annual message as president to attack the Reconstruction Acts. He claimed that: "The attempt to place the white population under the domination of persons of color in the South has impaired, if not destroyed, the friendly relations that had previously existed between them; and mutual distrust has engendered a feeling of animosity which, leading in some instances to collision and bloodshed, has prevented the cooperation between the two races so essential to the success of industrial enterprise in the Southern States."

Johnson retired from office in March 1869. He returned to his 350 acre farm near Greenville, Tennessee. Soon afterwards his son, Robert Johnson, who had been unable to overcome his alcoholism, committed suicide. His sole remaining son, Andrew Johnson, wrote from Georgetown College, promising his parents that he would never "let any kind of intoxicating liquor" pass his lips.

Andrew Johnson failed in his attempt to win a seat in the Senate in 1869. He was also unsuccessful in his bid for a seat in the House of Representatives in 1872. However, he was elected to the Senate shortly before his death at Carter Station, Tennessee, on 31st July, 1875.

On this day in 1909 Ethel MacDonald, one of nine children, was born in Bellshill. She left home at sixteen and did a variety of jobs over the next couple of years.

MacDonald joined the Independent Labour Party (ILP) and according to to Daniel Gray, the author of Homage to Caledonia (2008), she was "a working class woman of some erudition, she became local ILP secretary in her teens, and became fluent in French and German".

In 1931 Ethel MacDonald met Guy Aldred in Glasgow. Impressed by her revolutionary zeal he appointed her secretary of the Anti-Parliamentary Communist Federation (APCF), an organization formed by Aldred in 1921. The APCF was breakaway group from the Communist Party of Great Britain.

In June 1934 Ethel MacDonald and Aldred and were both involved in the formation of the United Socialist Movement (USM), an anarcho-communist political organisation based in Scotland. Several members of the Independent Labour Party who had lost their belief in the parliamentary road to socialism joined the party. MacDonald, like other members of the USM, had been deeply influenced by the ideas of William Morris.

On the outbreak of the Spanish Civil War she travelled with Jenny Patrick, Aldred's wife, to Barcelona as a representative of the USM. Soon afterwards she was employed by the CNT-FAI's foreign language information centre. Later she gave nightly English-language political broadcasts on Radio Barcelona.

On 14th November, 1936 Buenaventura Durruti arrived in Madrid from Aragón with his Anarchist Brigade. Six days later Durruti was killed while fighting on the outskirts of the city. Durruti's supporters in the CNT claimed that he had been murdered by members of the Communist Party (PCE).

Over the next few months the National Confederation of Trabajo (CNT), the Federación Anarquista Ibérica (FAI) and the Worker's Party (POUM) played an important role in running Barcelona. This brought them into conflict with other left-wing groups in the city including the Union General de Trabajadores (UGT), the Catalan Socialist Party (PSUC) and the Communist Party (PCE). MacDonald became involved in this conflict and in January 1937 she began to transmit regular English-language reports on the war on the radio station run by the CNT.

Ethel MacDonald soon had a strong following for her radio broadcasts. The Glasgow Herald reported: "A prominent news editor in Hollywood says that he has received hundred of letters concerning Ethel MacDonald, stating that the writers, in all parts of the USA and Canada, enjoyed her announcements and talks from Barcelona radio, not because they agreed with what she said, but because they thought she had the finest radio speaking voice they had ever heard."

In one broadcast she argued: "There is no doubt that they magnificent struggle of the Spanish workers challenges the entire theory and historical interpretation of parliamentary socialism. The civil war is a living proof of the futility and worthlessness of parliamentary democracy as a medium for social change."

On the 3rd May 1937, Rodriguez Salas, the Chief of Police, ordered the Civil Guard and the Assault Guard to take over the Telephone Exchange, which had been operated by the CNT since the beginning of the Spanish Civil War. Members of the CNT in the Telephone Exchange were armed and refused to give up the building. Members of the CNT, FAI and POUM became convinced that this was the start of an attack on them by the UGT, PSUC and the PCE and that night barricades were built all over the city.

Fighting broke out on the 4th May. Later that day the anarchist ministers, Federica Montseny and Juan Garcia Oliver, arrived in Barcelona and attempted to negotiate a cease-fire. When this proved to be unsuccessful, Juan Negrin, Vicente Uribe and Jesus Hernández called on Francisco Largo Caballero to use government troops to takeover the city. Largo Caballero also came under pressure from Luis Companys, the leader of the PSUC, not to take this action, fearing that this would breach Catalan autonomy.

On 6th May death squads assassinated a number of prominent anarchists in their homes. The following day over 6,000 Assault Guards arrived from Valencia and gradually took control of Barcelona. It is estimated that about 400 people were killed during what became known as the May Riots. During this crackdown MacDonald assisted the escape of anarchists wanted by the Communist secret police. As a result she became known as the "Scots Scarlet Pimpernel".

On 12th June, 1937, Bob Smillie, a member of the Independent Labour Party, who had been fighting with the POUM forces, died while being held by the Valencia police. He officially died from peritonitis. However, rumours began to circulate that he had died following a beating in his prison cell. MacDonald now began writing newspaper articles and making radio broadcasts claiming that Smillie had been executed by the secret police.

Eventually she herself was arrested by the authorities. She later told the Glasgow Evening Times: "My arrest was typical of the attitude of the Communist Party... Assault Guards and officials of the Public Order entered the house in which I lived late one night. Without any explanation they commenced to go through thoroughly every room and every cupboard in the house. After having discovered that which to them was sufficient to hang me - revolutionary literature etc."

Fenner Brockway of the Independent Labour Party worked behind the scenes to obtain MacDonald's release. He argued "she is an anarchist and has no connection with our party". On 8th July 1937, Ethel MacDonald was released in prison. However, within a few days she was rearrested again and spent another 12 days in captivity. When she was freed she went into hiding in Barcelona. She wrote to Guy Aldred and told him: "I am still here and unable to leave the country legally. I am in hiding... I cannot get a visa. If I apply I shall be arrested."

Ethel MacDonald's mother received a letter from Helen Lennox saying that her daughter's was in danger because of what she knew about the Bob Smillie case: "The Secret Service operating today in Spain comes by night and its victims are never seen again. Bob Smillie they didn't dare to bump off openly, but he may have suffered more because of that. Your Ethel certainly believes his death was intended. She prophesied it before his death took place, and said he would not be allowed out of the country with the knowledge he had. What worries me more than anything is that Ethel has already been ill and would be easy prey for anyone trying to make her death appear natural."

In September 1937 MacDonald managed to escape from Spain. After leaving the country she made speeches on the way the Communist Party (PCE) had been acting in during the Spanish Civil War in Paris and Amsterdam. She returned to Glasgow in November, 1937 and in a speech to 300 people at Central Station she said: "I went to Spain full of hopes and dreams. It promised to be utopia realised. I return full of sadness, dulled by the tragedy I have seen. I have lived through scenes and events that belong to the French revolution."

MacDonald also argued that Bob Smillie had been killed by the officials of the Communist Party (PCE). According to Daniel Gray, the author of Homage to Caledonia (2008): "she did her utmost to convince the public that Bob Smillie had been murdered, alleging that the secret police had assassinated him in cold blood."

David Murray, the Independent Labour Party representative in Spain, denied this and he wrote to John McNair saying: "Ethel MacDonald has been quite a trouble and my tactics are to choke her off. Murray's story was accepted until George Orwell arrived back in London. In his book, Homage to Catalonia (1938), Orwell argued that Smillie had died "an evil and meaningless death".

Alex Smillie, Bob's father, became convinced that his son had been murdered. David Murray wrote to him arguing: "I am convinced, and this I can affirm on oath, that Bob died a natural death. All my observations and impressions lead me to this conclusion. Judgement is a human thing and liable to error, but in spite of every curious and mysterious circumstance, I am convinced that Bob was never ill-treated nor was he done to death."

Georges Kopp, Smillie's commander in Spain, also argued that Smillie had been murdered: "The doctor states that Bob Smillie had the skin and the flesh of his skin perforated by a powerful kick delivered by a foot shod in the nailed boot; the intestines were partly hanging outside. Another blow had severed the left side connection between the jaw and the skull and the former was merely hanging on the right side. Bob died about 30 minutes after reaching the hospital."

After her return from Spain, Ethel MacDonald joined forces with Guy Aldred, Jenny Patrick, John Taylor Caldwell to establish The Strickland Press, which published regular issues of the USM organ, The Word. MacDonald considered as the unofficial manager, bookkeeper and printer of the Strickland Press.

Ethel MacDonald was diagnosed with multiple sclerosis in February 1958 and lost her ability to speak. Within three years she died in Glasgow's Knightswood Hospital at the age of 51, on 1st December 1960.

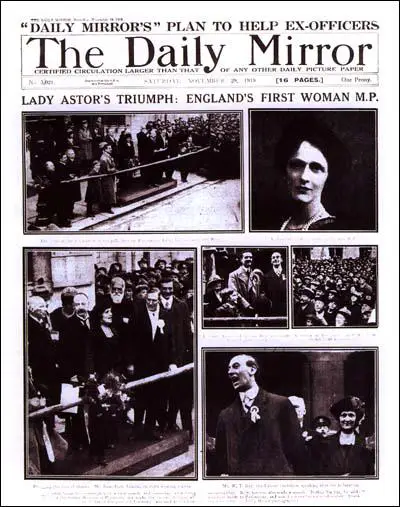

On this day in 1920 Nancy Astor becomes the first woman to speak in the House of Commons. In 1904 Nancy met and married the immensely wealthy Waldorf Astor. She later commented: "I married beneath me, all women do." The couple moved into Cliveden, a large estate in Buckinghamshire on the River Thames. They also had a home in St. James's Square.

Waldorf Astor was a member of the Conservative Party and represented the Sutton division of Plymouth in the House of Commons. On the death of his father in 1919, Astor became a member of the House of Lords. Nancy now became the party's candidate in the resulting by-election. Oswald Mosley was one of those who campaigned for her in the election: "She was less shy than any woman - or any man - one has ever known. She'd address the audience and then she'd go across to some old woman scowling in a neighbouring doorway, who simply hated her, take both her hands and kiss her on the cheek or something of that sort. She was absolutely unabashed by any situation. Great effrontery but also, of course, enormous charm. People were usually overcome by it. She was much better when she was interrupted. She must have prayed for hecklers and interrupters. She certainly got a lot."

Nancy Astor beat the Liberal Party candidate, Isaac Foot, and on 1st December 1919 became the first woman to take her seat in the House of Commons (the first woman to be elected was Constance Markievicz in 1918 but as a member of Sinn Fein had disqualified herself by refusing to take the oath). Markievicz, like many feminists, was highly critical that a woman who had not been part of the suffrage campaign had been elected to parliament. She accused her being a member of the "upper classes" and "out of touch" with the needs of ordinary people. Norah Dacre Fox, one of the leaders of the Women's Social and Political Union pointed out: "the first woman to be elected for an English constituency was an American born citizen, who had no credentials to represent British women in their own parliament save that she had married a British subject." Rachel Strachey said she was "lamentably ignorant of everything she ought to know".

Astor's maiden speech was in favour of the Temperance Society and in 1923 she introduced a private member's bill that raised to eighteen the age qualification for the purchase of alcoholic drinks. Astor worked closely with Margaret Wintringham, the second woman to be elected to the House of Commons. In a speech in July 1923 she argued: "In 1920 nearly 2,000 persons were cautioned by these women police for acts of indecency in parks and public places. There were nearly 3,000 persons cautioned for unseemly behaviour in parks, and 2,700 young girls were cautioned for loitering in the streets, and advised as to the danger of doing so; 1,000 girls passed into homes and hospitals, and 6,400 respectable girls and women stranded at night were found shelter. We had the evidence of Sir Nevil Macready, Sir Leonard Dunning, and chief constables and social workers, and the Committee unanimously reported that in thickly populated areas, where offences against the law relating to women and children are not infrequent, there was not only scope, but urgent need, for the employment of women police, and they also said that the women should be specially qualified, highly trained and well paid."

In the 1930s Nancy Astor and her husband, Waldorf Astor held regular weekend parties at their home Cliveden, a large estate in Buckinghamshire on the River Thames. Those who attended included Philip Henry Kerr (11th Marquess of Lothian), Edward Wood (1st Earl of Halifax), Geoffrey Dawson, Samuel Hoare, Lionel Curtis, Nevile Henderson, Robert Brand and Edward Algernon Fitzroy. Most members of the group were supporters of a close relationship with Adolf Hitler and Nazi Germany. The group included several influential people. Astor owned The Observer, Dawson was editor of The Times, Hoare was Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs, Lord Halifax was a minister of the government who would later become foreign secretary and Fitzroy was Speaker of the Commons.

Norman Rose, the author of The Cliveden Set (2000): "Lothian, Dawson, Brand, Curtis and the Astors - formed a close-knit band, on intimate terms with each other for most of their adult life. Here indeed was a consortium of like-minded people, actively engaged in public life, close to the inner circles of power, intimate with Cabinet ministers, and who met periodically at Cliveden or at 4 St James Square (or occasionally at other venues). Nor can there be any doubt that, broadly speaking, they supported - with one notable exception - the government's attempts to reach an agreement with Hitler's Germany, or that their opinions, propagated with vigour, were condemned by many as embarrassingly pro-German."

On 17th June, 1936, Claude Cockburn, produced an article called "The Best People's Front" in his anti-fascist newsletter, The Week. He argued that a group that he called the Astor network, were having a strong influence over the foreign policies of the British government. He pointed out that members of this group controlled The Times and The Observer and had attained an "extraordinary position of concentrated power" and had become "one of the most important supports of German influence".

A copy of this newspaper can be obtained from Historic Newspapers.

On this day in 1923 the Daily Express publish an article on German inflation. "A Berlin couple who were about to celebrate their golden wedding received an official letter advising them that the mayor, in accordance with Prussian custom, would call and present them with a donation of money. Next morning the mayor, accompanied by several aldermen in picturesque robes, arrived at the aged couple's house, and solemnly handed over in the name of the Prussian State, 1,000,000,000,000 marks or one halfpenny."

After the First World War Germany suffered from inflation. In January, 1921, there were 64 marks to the dollar. By November, 1923 this had changed to 4,200,000,000,000 marks to the dollar. Some politicians in the United States and Britain began to realize that the terms of the Versailles Treaty had been too harsh and in April 1924 Charles Dawes presented a report on German economic problems to the Allied Reparations Committee. The report proposed a plan for regulating annual payments of reparations and the reorganizing the German State Bank so as to stabilize the currency. Promises were also made to provide Germany with foreign loans.

These policies were successful and by the end of 1924 inflation had been brought under control and the economy began to improve. By 1928 unemployment had fallen to 8.4 per cent of the workforce. The German people gradually gained a new faith in their democratic system and began to find the extremist solutions proposed by people such as Adolf Hitler unattractive.

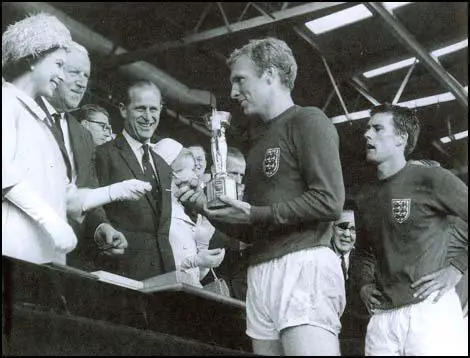

On this day in 1993 Bobby Moore died. Robert "Bobby" Moore, the only son of Robert (Bob) and Doris Moore, was born in Upney Hospital on 12th April 1941, during the Blitz. His aunt, Ena Herbert, recalled: "Little Robert was delivered in Upney hospital... Doris stayed in the hospital that night and came home to Waverley Gardens the next day... That night there was a very heavy German bombing raid and an explosion in the neighbourhood blasted ceilings down and blew windows in... Bob's mother and Bob laid across the baby and Doris to protect them from injury. The raid was so bad they had to evacuate Doris and little Robert from Waverley Gardens, which was near the industrial area, close to the power station on the river, which was a target for the German bombs."

The Moore family lived at 43 Waverley Gardens in Barking and Bobby attended Westbury Primary School. His parents supported Barking Football Club and attended all their home and away games. Moore passed his 11-plus and went to Tom Hood Technical High School in Leyton. Moore later recalled: "The first two months were murder. I was the only boy from my district. Up at seven a.m., on my own on the bus from home to Barking station, train to Wanstead, trolleybus to Leyton, long walk to the school. I was sick with it. I went to the doctor pining for any sort of school in Barking and got a certificate for a transfer on the grounds of travel sickness." However, Moore decided to continue at the school.

Joan Wright, one of his teachers at Tom Hood Technical High School later recalled: "At school he was a prefect... He was very popular. It was a technical and commercial school and Bobby passed the equivalent of nearly half a dozen 'O' levels in one go. whenever there were pupils who wanted to become footballers and thought they didn't have to try at academic work. I'd point out Bobby Moore as an example to show it is possible to do both."

While at secondary school Moore played for Leyton District Under-13s. During one game he was seen by a West Ham United scout and he was invited to train at Upton Park. Moore found the experience difficult: "I was ordinary. I was lucky to be there. and every time I looked at one of the other lads I knew it. Every one of them had played for Essex or London, and at least been for trials with England Schoolboys. I had nothing. All around me were players with unbelievable ability. They were the same age as me and I was looking up at them and wishing I was that good, that skillful."

Moore later pointed out: "The first time I got a representative game I played for Essex over-15s because they needed a makeshift centre forward. I kept lumbering down the middle until our keeper hit a big up-and-under clearance which their keeper caught as I bundled him into the net... The referee was weak and gave the goal for Essex. Everyone knew it was a joke. Most of all, the lads who knew they were better than me." During this period Moore suffered from an inferiority complex. "The best quality I had was wanting to succeed."

Moore was invited to train with the West Ham Colts. His ability was noticed by Malcolm Allison, the West Ham United defender who had been asked by Ted Fenton, the club manager, to coach the young players. "Fenton used to pay me £3 extra for training the schoolboys at night. It was then that I found I had a bit of a gift for spotting the boys most likely to make it as professionals.... After a fortnight of training the boys Fenton called me into his office to ask my opinion of the intake." Fenton asked him about Georgie Fenn, who had scored nine goals in one match for England Schoolboys: "I said that I didn't give him much of a chance. I didn't like his attitude, he wasn't interested enough. There didn't seem much of a commitment... At the same time I said that Bobby Moore was going to be a very big player indeed. Everything about his approach was right. He was ready to listen. You could see that already he was seeking perfection."

In August 1950, Bobby Moore signed amateur forms for West Ham United. He joined the club full-time after leaving school on 19th July, 1957. Ron Greenwood, was with Fulham when he first saw Bobby Moore play: "I saw Bobby play for London Schoolboys against Glasgow at Stamford Bridge. Even at 16 he had stature, a certain appearance, an awareness of the game others did not possess." When Greenwood became manager of the England Youth team he selected Moore as his captain: "He was thirsty for knowledge and I spent hours talking to him about the game, whenever there was a free moment. When we had trips away he almost raided you for knowledge."

Malcolm Allison also noticed his leadership qualities. "He was very inquisitive. Even then I had spotted his awareness for the game, his ability to recognise things so easily. He had a clever memory and he was very bright. Allison told Moore: "You can read the game, you know what to do... Be in control of yourself. Take control of everything around you. Look big. Think big. Tell people what to do. Be in command." Noel Cantwell was one of the senior players at the club at the time: "Bobby didn't have exceptional ability as an apprentice, although he was always immaculate. He never said very much but was a great listener and a dedicated trainer, always very curious, inquisitive guy who wanted answers. He fastened on to Malcolm Allison and myself because we talked football all the time."

Bobby Moore recalled in his autobiography: "When Malcolm was coaching schoolboys he took a liking to me when I don't think anyone else at West Ham saw anything special in me... I looked up to the man. It's not too strong to say I loved him." Eddie Lewis was a member of the West Ham squad during this period. He observed the help that Allison gave to Moore: "The man deserves a great deal of credit for bringing on the likes of Bobby Moore. As a kid, Bobby was slow, he couldn't head a ball and he couldn't tackle, but such was Malcolm's dedication he was able to help Bobby to become the player he was." Harry Redknapp claims that Allison valued Moore so much that "Malcolm would bring him to training and drive him home."

Bobby Moore put a lot of effort into his training. Geoff Hurst recalled: "I remember how impressed I'd been with this blond-haired youngster from Barking when I first started training at West Ham. When we were doing exercises to strengthen the stomach muscles we had to lie on our backs, raise our legs in the air and hold them there. Try it yourself. If you are not used to it you will quickly discover how painful this can be. Of the 50 or so players doing this exercise the last to lower his legs was Bobby Moore. Always." Frank Lampard agreed: "You could see how some trained better than others, some were good runners, some were bad, but every time you looked over at the first team training, Bobby was the one training hard." John Bond was another player who was impressed with Bobby Moore: "Bobby's ability to intake information was tremendous, he wanted to learn and allowed nothing to interfere with his football. People used to tell him things and he would learn very quickly."

Moore played in a youth match against Chelsea where he marked the highly talented Barry Bridges: "I marked Bridges and followed him all over the field, wherever he went. We drew 0-0 and I was really pleased with myself and I thought Malcolm would give me a pat on the back at the end of the game." Instead Malcolm Allison came into the dressing-room and shouted: "If I ever see you play like that again, I'll never talk to you again. You just followed Bridges all over the field. When your goalkeeper got the ball, you never dropped back and made the goalkeeper roll it out so you could start attacks from the back, did you? When your left-back got it, you didn't drop inside so he could pass it square, so you could chip the ball up to the centre-forward, did you? I want to see you do those things and if you can't, don't talk to me. I'm not giving you any more lifts home."

Moore told Harry Redknapp that this outburst completely changed the way he played the game: "If you look at Bobby's game, he would come and get it off the goalie and play it out, starting attacks, and he would drop off, get the ball from the left-back and chip it into Hurstie's chest. That was an essential part of his game."

On 16th September, 1957, Malcolm Allison was taken ill after a game against Sheffield United. Moore later recalled: "I'd even seen him the day he got the news of his illness. I was a groundstaff boy and I'd gone to Upton Park to collect my wages. I saw Malcolm standing on his own on the balcony at the back of the stand. Tears in his eyes. Big Mal actually crying. He'd been coaching me and coaching me and coaching me but I still didn't feel I knew him well enough to go up and ask what was wrong. When I came out of the office I looked up again and Noel Cantwell was standing with his arm round Malcolm. He'd just been told he'd got T.B."

Allison was suffering from tuberculosis and he had to have a lung removed. Noel Cantwell became the new captain. That season West Ham United won the Second Division championship. The authors of The Essential History of West Ham United point out that Allison was the main reason the club had won promotion: "A footballing visionary who in six short years would revolutionise the club's archaic regime and transform training, coaching techniques and tactics to secure promotion to the first division in 1958".

Allison returned to the club and played several games for the reserves but with only one lung he struggled with his fitness. West Ham had an injury crisis for its home game against Manchester United on 8th September 1958. Malcolm Pyke, Bill Lansdowne and Andy Nelson were all injured. The manager, Ted Fenton asked Noel Cantwell who he should select for the game. Cantwell told Brian Belton, the author of Days of Iron: The Story of West Ham United in the Fifties (1999): "The game against Manchester United was on a Monday night. Fenton called me into the office asking who should play left-half, Allison or Moore. He didn't really want the burden of the decision."

Cantwell added in another interview for the book, Moore than a Legend (1997): "Malcolm came out of hospital and trained while Bobby was cruising along in the reserves. Malcolm was ready for the United game but the vacancy was for a left-half. Malcolm was more of a stopper and it needed someone more mobile. When Ted asked me who to pick, it was a hard decision. The sorcerer or his apprentice?" Cantwell eventually selected Moore over Allison.

Bobby Moore later talked about this decision to Jeff Powell for this book, Bobby Moore: The Life and Times of a Sporting Hero (1997): "The Allison connection could only be dredged up from the bottom of a long, long glass. Even then, Moore probed gingerly at the memory". Eventually Moore told him: " After three or four matches they were top of the First Division, due to play Manchester United on the Monday night, and they had run out of left halves. Billy Lansdowne, Andy Nelson, all of them were unfit. It's got to be me or Malcolm. I'd been a professional for two and a half months and Malcolm had taught me everything I knew. For all the money in the world I wanted to play. For all the money in the world I wanted Malcolm to play because he'd worked like a bastard for this one game in the First Division."

Bobby Moore added: "It somehow had to be that when I walked into the dressing room and found out I was playing, Malcolm was the first person I saw. I was embarrassed to look at him. He said Well done. I hope you do well. I knew he meant it but I knew how he felt. For a moment I wanted to push the shirt at him and say Go on, Malcolm. It's yours. Have your game. I can't stop you. Go on, Malcolm. My time will come. But he walked out and I thought maybe my time wouldn't come again. Maybe this would be my only chance. I thought: you've got to be lucky to get the chance, and when the chance comes you've got to be good enough to take it. I went out and played the way Malcolm had always told me to play."

Malcolm Musgrove was a member of the West Ham side that played against Manchester United: "He played in the game as though he'd been in the side for years. I was a lot older than Bobby at the time and I was still a novice, nervous as hell. At the kickoff Bobby stood in the left-half position just looking round. He had an unbelievable temperament. Lots of players have ability, but they haven't got the temperament to make them go even further, as far as they might want to go - Bobby had that temperament."

Moore did a good job marking Ernie Taylor and West Ham won the game 3-2. After the game Malcolm Allison stormed into the dressing-room and confronted Noel Cantwell about the advice he had given Ted Fenton. Cantwell later commented: "How he got to know I had influenced Ted's decision for Bobby to play, I'll never know. I didn't say any more. It was an embarrassing position for me and it soured the night, although I had answered Ted's question with the right choice for the particular match. Later, Malcolm admitted I was right to choose Bobby."

The next game was against Nottingham Forest at home. Moore was dropped from the team after West Ham United lost 4-0. He played only three more games that season as John Smith became the regular left-half. Moore had the same problem in the 1960-61 season. Moore later told Jeff Powell that he "doubted he would ever have broken through had West Ham not sold John Smith to Tottenham". Moore added: "You've got to be lucky even if you know you're good enough to take the chance if it comes. If John hadn't gone to Spurs I might have been a reserve footballer who threw in the towel, gave up the game."

Moore was nearly 20 when he became a regular member of the first-team. He did not approve of the tactics employed by Ted Fenton: "He wanted us to hit long through balls from the half way line. We became the world's best hitters of long through balls to nobody from the half way line. We seemed to lose every match 4-0."

Tom Finney, the veteran winger, spotted Moore's ability as a defender when he was just still a teenager. He pointed out in My Autobiography (2003): "It was an outstanding display from the 19-year-old. Perfect of temperament, he (Moore) always seemed to have so much time on the ball - the sign of a great player. He was strong in the challenge and was never hassled or harried out of his easy stride. He read the game brilliantly and had undisputed star quality."

When Ron Greenwood became manager of the England Under-23 side, he made Moore his captain. Greenwood, was assistant manager at Arsenal at the time, advised Jack Crayston to buy him. According to Moore: “One of Ron’s pet journalists come on my ear about getting away from West Ham to Arsenal… If the chance had come I would have loved to have gone to Arsenal for the same reason that Spurs appealed… a big club. But I suppose when they made the official approaches West Ham knocked them back.”

Moore played in 38 games in the 1960-61 season but the club finished in 16th position. However, his own form was very good. Peter Brabrook, who was playing at Chelsea at the time, found him a very difficult opponent. "When we played West Ham, I always roasted Noel Cantwell, the left-back, who was probably the best left-back in the country. But I could never seem to get past Bobby. He was nowhere near as quick as Noel or me but he never let you get in a position to beat him - he led you into a trap and caught you by the byline or the corner flag."

Ken Brown played alongside Moore during this period: "We were centre-halves for West Ham. I was the stopper and Bobby was the play-maker. My strength was heading and safety first, his strength was control and weighted passing. He could volley or one-touch a pass without looking and you wouldn't struggle to reach it, it would drop at your feet... My natural instinct was to cover him in case he missed a ball but I can't remember him ever bloody missing it. He was so consistent."

On 16th March 1961 the chairman of the club stated: "For some time, Mr Fenton had been working under quite a strain and it was agreed that he should go on sick leave. For the time being, we shall carry on by making certain adjustments in our internal administration." The Ilford Recorder added that: "The Upton Park club are proud of their tradition of never having sacked a manager." This was untrue as Syd King had been dismissed in 1933. Fenton had also been sacked and was replaced by Ron Greenwood.

Malcolm Allison later claimed that "Ted Fenton got the sack. They were rebuilding the stand and he was pinching some bricks and paint. Putting it in the back of the car. One of the directors caught him." Ken Tucker thought he had been dismissed because he had negotiated a reduction in the price of equipment, but was only passing on a percentage of the savings to the club. However, Andy Smillie believes that Fenton was a victim of "player power".

Charles Korr, the author of West Ham United: The Making of a Football Club (1986) has argued that the appointment of Greenwood was a break with the past: "When supporters think of managers it is usually in terms of the success of the club. There is little else upon which to judge them. West Ham had been different in this respect because its pre-greenwood managers had been with the club for so long in some capacity that supporters could identify with them. The manager at West Ham was something much more than a transitory employee. Greenwood's employment changed all those perceptions. He was not 'an old boy', and he made no attempt to add affections that would give the impressions that he was part of West Ham tradition."

It is not generally known but Greenwood, who was assistant manager of Arsenal, initially rejected the job. He told one journalist that he was not interested in the job because "If they can get rid of one manager they can get rid of another." He changed his mind when he discovered that Ted Fenton was only the third manager in over 60 years. The other attraction was the quality of West Ham's young players. In fact, Greenwood's first trophy came when West Ham United beat Liverpool 6-5 in the 1963 Youth Cup. The score-line reflects the success and problems of the tactics used by Greenwood.

Bobby Moore, who had played under Ron Greenwood for the England Youth team, was pleased with the appointment. He told Geoff Hurst: "I've played under Ron at England Under-23 level. Things are going to change around here, this chap is incredible on the game." Moore informed his close friend, Jeff Powell: "Ron told me one of his major reasons for coming to West Ham was that he knew he had me there to start building his team around." Greenwood rated Moore very highly: "He was exceptional on the training ground, a coach's dream. Whatever you asked him to do, he could do it. Football came easy to him. It wasn't a question of teaching him, merely a question of honing his considerable abilities... I used him at West Ham as a sweeper, which was then an unknown position. He played loose behind the defence and he thrived there." John Cartwright agreed: "Bobby played it superbly and it was his spot forever more. There have probably been players physically and technically better than Bobby but few tackled as astutely as he did."

Greenwood sold Noel Cantwell to Manchester United and made Phil Woosnam captain. He also purchased the extremely talented Johnny Byrne for £65,000. He played him alongside Geoff Hurst. As Bobby Moore pointed out: "Greenwood turned Geoff Hurst from a bit of a cart-horse at wing-half into a truly great forward. None of us thought Geoff was going to make the switch... Playing up alongside Budgie must have helped. That man was magic." Greenwood also gave Martin Peters his debut. Moore claimed that: "He was virtually a complete player. In addition to all his talent he had vision and awareness and a perfect sense of timing."